Section 5: Infancy and Toddlerhood

5.2 Cognitive Development in Infancy and Toddlerhood

What’s cognitive development like in the first two years?

In addition to rapid physical growth, infants also exhibit significant development of their cognitive abilities, particularly in language acquisition and in the ability to think and reason. You already learned a little bit about Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, and in this section, we’ll apply that model to cognitive tasks during infancy and toddlerhood. Piaget described intelligence in infancy as sensorimotor or based on direct, physical contact, where infants use senses and motor skills to taste, feel, pound, push, hear, and move in order to experience the world. These basic motor and sensory abilities provide the foundation for the cognitive skills that will emerge during the subsequent stages of cognitive development.

Learning Objectives

- Describe Piaget’s sub-stages of sensorimotor intelligence

- Explain learning and memory abilities in infants and toddlers

- Describe stages of language development during infancy

- Compare theories of language development in toddlers

- Explain the procedure, results, and implications of moral reasoning research in infants

Cognitive Development in Infants

In order to adapt to the evolving environment around us, humans rely on cognition, both adapting to the environment and also transforming it. In general, all theorists studying cognitive development address three main issues:

- The typical course of cognitive development

- The unique differences between individuals

- The mechanisms of cognitive development (the way genetics and environment combine to generate patterns of change)

The Cognitive Perspective: The Roots of Understanding

Cognitive theories focus on how our mental processes or cognitions change over time. The theory of cognitive development is a comprehensive theory about the nature and development of human intelligence, first developed by Jean Piaget. It is primarily known as a developmental stage theory, but in fact, it deals with the nature of knowledge itself and how humans come gradually to acquire it, construct it, and use it. Moreover, Piaget claims that cognitive development is at the center of the human organism, and language is contingent on cognitive development. Let’s learn more about Piaget’s views about the nature of intelligence and then dive deeper into the stages that he identified as critical in the developmental process.

Stages of Cognitive Development

Like Freud and Erikson, Piaget thought development unfolded in a series of stages approximately associated with age ranges. He proposed a theory of cognitive development that unfolds in four stages: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational.

| Table 1. Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development | |||

| Age (years) | Stage | Description | Developmental issues |

| 0–2 | Sensorimotor | World experienced through senses and actions | Object permanence Stranger anxiety |

| 2–7 | Preoperational | Use words and images to represent things but lack logical reasoning | Pretend play Egocentrism Language development |

| 7–11 | Concrete operational | Understand concrete events and logical analogies; perform arithmetical operations | Conservation Mathematical transformations |

| 11– | Formal operational | Utilize abstract reasoning and hypothetical thinking | Abstract logic Moral reasoning |

Piaget and Senorimotor Intelligence

How do infants connect and make sense of what they are learning? Remember that Piaget believed that we are continuously trying to maintain cognitive equilibrium, or balance, between what we see and what we know (Piaget, 1954). Children have much more of a challenge in maintaining this balance because they are constantly being confronted with new situations, new words, new objects, etc. All this new information needs to be organized, and a framework for organizing information is referred to as a schema. Children develop schemas through the processes of assimilation and accommodation.

For example, 2-year-old Deja learned the schema for dogs because her family has a Poodle. When Deja sees other dogs in her picture books, she says, “Look, mommy, dog!” Thus, she has assimilated them into her schema for dogs. One day, Deja sees a sheep for the first time and says, “Look, mommy, dog!” Having a basic schema that a dog is an animal with four legs and fur, Deja thinks all furry, four-legged creatures are dogs. When Deja’s mom tells her that the animal she sees is a sheep, not a dog, Deja must accommodate her schema for dogs to include more information based on her new experiences. Deja’s schema for dogs was too broad since not all furry, four-legged creatures are dogs. She now modifies her schema for dogs and forms a new one for sheep.

Let’s examine the transition that infants make from responding to the external world reflexively as newborns to solving problems using mental strategies as two-year-olds. Piaget called this first stage of cognitive development sensorimotor intelligence (the sensorimotor period) because infants learn through their senses and motor skills. He subdivided this period into six substages:

|

Table 2. Sensorimotor substages |

|

|

Stage |

Age |

|

Stage 1 – Reflexes |

Birth to 6 weeks |

|

Stage 2 – Primary Circular Reactions |

6 weeks to 4 months |

|

Stage 3 – Secondary Circular Reactions |

4 months to 8 months |

|

Stage 4 – Coordination of Secondary Circular Reactions |

8 months to 12 months |

|

Stage 5 – Tertiary Circular Reactions |

12 months to 18 months |

|

Stage 6 – Mental Representation |

18 months to 24 months |

Substages of Sensorimotor Intelligence

It helps to group the six substages of sensorimotor thought into pairs for an overview.

The first two substages involve the infant’s responses to its own body, called primary circular reactions. During the first month (substage one), the infant’s senses and motor reflexes are the foundation of thought.

Substage One: Reflexive Action (Birth through 1st month)

This active learning begins with automatic movements or reflexes (sucking, grasping, staring, listening). A ball comes into contact with an infant’s cheek and is automatically sucked on and licked. But this is also what happens with a sour lemon, much to the infant’s surprise! The baby’s first challenge is to learn to adapt the sucking reflex to bottles or breasts, pacifiers or fingers, each acquiring specific types of tongue movements to latch, suck, breathe, and repeat. This adaptation demonstrates that infants have begun to make sense of sensations. Eventually, the use of these reflexes becomes more deliberate and purposeful as they move onto substage two.

Substage Two: First Adaptations to the Environment (1st through 4th months)

Fortunately, within a few days or weeks, the infant begins to discriminate between objects and adjust responses accordingly as reflexes are replaced with voluntary movements. An infant may accidentally engage in a behavior and find it interesting, such as making a vocalization. This interest motivates trying to do it again and helps the infant learn a new behavior that originally occurred by chance. The behavior is identified as circular and primary because it centers on the infant’s own body. At first, most actions have to do with the body, but in months to come, they will be directed more toward objects. For example, the infant may have different sucking motions for hunger and others for comfort (i.e. sucking a pacifier differently from a nipple or attempting to hold a bottle to suck it).

The next two substages (3 and 4) involve the infant’s responses to objects and people, called secondary circular reactions. Reactions are no longer confined to the infant’s body and are now interactions between the baby and something else.

Substage Three: Repetition (4th through 8th months)

During the next few months, the infant becomes increasingly actively engaged in the outside world and delights in making things happen by responding to people and objects. Babies try to continue any pleasing event. Repeated motion brings particular interest, as the infant is able to bang two lids together or shake a rattle and laugh. Another example might be clapping their hands when a caregiver says, “Patty-cake.” Any sight of something delightful will trigger efforts for interaction.

Substage Four: New Adaptations and Goal-Directed Behavior (8th through 12th months)

Now, the infant becomes more deliberate and purposeful in responding to people and objects and can engage in behaviors that others perform and anticipate upcoming events. Babies may ask for help by fussing, pointing, or reaching up to accomplish tasks and work hard to get what they want. Perhaps because of continued maturation of the prefrontal cortex, the infant becomes capable of having a thought and carrying out a planned, goal-directed activity such as seeking a toy that has rolled under the couch or indicating that they are hungry. The infant is coordinating both internal and external activities to achieve a planned goal and begins to get a sense of social understanding. Piaget believed that at about 8 months (during substage 4), babies first understood the concept of object permanence, which is the realization that objects or people continue to exist when they are no longer in sight.

The last two stages (5 and 6), called tertiary circular reactions, consist of actions (stage 5) and ideas (stage 6), during which infants become more creative in their thinking.

Substage Five: Active Experimentation of “Little Scientists” (12th through 18th months)

The toddler is considered a “little scientist” and begins exploring the world in a trial-and-error manner, using motor skills and planning abilities. For example, the child might throw their ball down the stairs to see what happens or delight in squeezing all of the toothpaste out of the tube. The toddler’s active engagement in experimentation helps them learn about their world. Gravity is learned by pouring water from a cup or pushing bowls from high chairs. The caregiver tries to help the child by picking it up again and placing it on the tray. And what happens? Another experiment! The child pushes it off the tray again causing it to fall and the caregiver to pick it up again! A closer examination of this stage causes us to really appreciate how much learning is going on at this time and how many things we come to take for granted must actually be learned. This is a wonderful and messy time of experimentation and most learning occurs by trial and error.

Substage Six: Mental Representations (18th month to 2 years of age)

The child is now able to solve problems using mental strategies, to remember something heard days before and repeat it, to engage in pretend play, and to find objects that have been moved even when out of sight. Take, for instance, the child who is upstairs in a room with the door closed, supposedly taking a nap. The doorknob has a safety device on it that makes it impossible for the child to turn the knob. After trying several times to push the door or turn the doorknob, the child carries out a mental strategy to get the door opened – he knocks on the door! Obviously, this is a technique learned from the past experience of hearing a knock on the door and observing someone opening the door. The child is now better equipped with mental strategies for problem-solving. Part of this stage also involves learning to use language. This initial movement from the “hands-on” approach to knowing about the world to the more mental world of stage six marked the transition to preoperational thinking, which you’ll learn more about in a later module.

Development of Object Permanence

A critical milestone during the sensorimotor period is the development of object permanence. Introduced during substage 4 above, object permanence is the understanding that even if something is out of sight, it continues to exist. The infant is now capable of making attempts to retrieve the object. Piaget thought that, at about 8 months, babies first understand the concept of objective permanence, but some research has suggested that Piaget underestimated infant cognitive abilities. Infants seem to be able to recognize that objects have permanence at much younger ages (even as young as 4 months of age).

Other researchers, however, are not convinced (Mareschal & Kaufman, 2012). It may be a matter of “grasping vs. mastering” the concept of objective permanence. Overall, we can expect children to grasp the concept that objects continue to exist even when they are not in sight by around 8 months old, but memory may play a factor in their consistency. Because toddlers (i.e., 12–24 months old) have mastered object permanence, they enjoy games like hide-and-seek, and they realize that when someone leaves the room, they will come back (Loop, 2013). Toddlers also point to pictures in books and look in the appropriate places when you ask them to find objects.

Infant Memory

Memory requires a certain degree of brain maturation, so it should not be surprising that infant memory is rather fleeting and fragile. As a result, older children and adults experience infantile amnesia, the inability to recall memories from the first few years of life. Several hypotheses have been proposed for this amnesia. From the biological perspective, it has been suggested that infantile amnesia is due to the immaturity of the infant’s brain, especially those areas that are crucial to the formation of autobiographical memory, such as the hippocampus. From the cognitive perspective, it has been suggested that the lack of linguistic skills of babies and toddlers limits their ability to mentally represent events, thereby reducing their ability to encode memory. Moreover, even if infants do form such early memories, older children and adults may not be able to access them because they may be employing very different, more linguistically based, retrieval cues than infants used when forming the memory. Finally, social theorists argue that episodic memories of personal experiences may hinge on an understanding of “self”, something that is clearly lacking in infants and young toddlers.

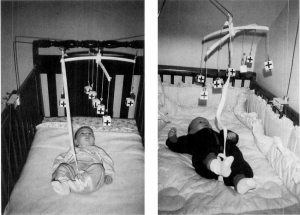

However, in a series of clever studies, Carolyn Rovee-Collier and her colleagues have demonstrated that infants can remember events from their lives, even if these memories are short-lived. Three-month-old infants were taught that they could make a mobile hung over their crib shake by kicking their legs. The infants were placed in their cribs on their backs. A ribbon was tied to one foot and the other end to a mobile. At first, infants made random movements but then came to realize that by kicking, they could make the mobile shake. After two 9-minute sessions with the mobile, the mobile was removed. One week later, the mobile was reintroduced to one group of infants, and most of the babies immediately started kicking their legs, indicating that they remembered their prior experience with the mobile. A second group of infants was shown the mobile two weeks later, and the babies made only random movements. The memory had faded (Rovee-Collier, 1987; Giles & Rovee-Collier, 2011). Rovee-Collier and Hayne (1987) found that 3-month-olds could remember the mobile after two weeks if they were shown the mobile and watched it move, even though they were not tied to it. This reminder helped most infants to remember the connection between their kicking and the movement of the mobile. Like many researchers of infant memory, Rovee-Collier (1990) found infant memory to be very context-dependent (Rovee-Collier, 1990). In other words, the sessions with the mobile and the later retrieval sessions had to be conducted under very similar circumstances or else the babies would not remember their prior experiences with the mobile. For instance, if the first mobile had had yellow blocks with blue letters, but at the later retrieval session the blocks were blue with yellow letters, the babies would not kick.

Infants older than 6 months of age can retain information for longer periods of time; they also need less reminding to retrieve information in memory. Studies of deferred imitation, that is, the imitation of actions after a time delay, can occur as early as six months of age (Campanella & Rovee-Collier, 2005), but only if infants are allowed to practice the behavior they were shown. By 12 months of age, infants no longer need to practice the behavior in order to retain the memory for four weeks (Klein & Meltzoff, 1999).

Language Development

Our vast intelligence also allows us to have language, a system of communication that uses symbols regularly to create meaning. Language allows us to communicate our intelligence to others by talking, reading, and writing. We will review several components of language.

Given the remarkable complexity of a language, one might expect that mastering a language would be an especially arduous task; indeed, for those of us trying to learn a second language as adults, this might seem to be true. However, young children master language very quickly and with relative ease. B. F. Skinner (1957) proposed that language is learned through reinforcement. Noam Chomsky (1965) criticized this behaviorist approach, asserting instead that the mechanisms underlying language acquisition are biologically determined. The use of language develops in the absence of formal instruction and appears to follow a very similar pattern in children from vastly different cultures and backgrounds. It would seem, therefore, that we are born with a biological predisposition to acquire a language (Chomsky, 1965; Fernández & Cairns, 2011). Moreover, it appears that there is a critical period for language acquisition, such that this proficiency at acquiring language is maximal early in life; generally, as people age, the ease with which they acquire and master new languages diminishes (Johnson & Newport, 1989; Lenneberg, 1967; Singleton, 1995).

Children begin to learn about language from a very early age (Table 3). In fact, it appears that this is occurring even before we are born. Newborns show a preference for their mother’s voice and appear to be able to discriminate between the language spoken by their mother and other languages. Babies are also attuned to the languages being used around them and show preferences for videos of faces that are moving in synchrony with the audio of spoken language versus videos that do not synchronize with the audio (Blossom & Morgan, 2006; Pickens, 1994; Spelke & Cortelyou, 1981).

| Age | Developmental Language and Communication |

|---|---|

| Newborn | Reflexive communication (e.g., cries) |

| to 3 months | Cooing |

| 4–6 months | Interest in others; begins babbling |

| 7–12 months | Understands common words; gestures |

| 12–18 months | First words |

| 18–24 months | Simple sentences of two words |

| 2–3 years | Sentences of three or more words |

| 3–5 years | Complex sentences; has conversations |

Components of Language

Phoneme: A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound that makes a meaningful difference in a language. The word “bit” has three phonemes. In spoken languages, phonemes are produced by the positions and movements of the vocal tract, including the lips, teeth, tongue, vocal cords, and throat, whereas in sign languages, phonemes are defined by the shapes and movements of the hands.

There are hundreds of unique phonemes that human speakers can make, but most languages only use a small subset of the possibilities. English contains about 45 phonemes, whereas other languages have as few as 15 and others more than 60. The Hawaiian language contains fewer phonemes as it includes only 5 vowels (a, e, i, o, and u) and 7 consonants (h, k, l, m, n, p, and w).

Infants are born able to detect all phonemes, but they lose their ability to do so as they get older; by 10 months of age, a child’s ability to recognize phonemes becomes very similar to that of the adult speakers of the native language. Phonemes that were initially differentiated come to be treated as equivalent (Werker & Tees, 2002).

Morpheme: Whereas phonemes are the smallest units of sound in language, a morpheme is a string of one or more phonemes that makes up the smallest units of meaning in a language. Some morphemes are prefixes and suffixes used to modify other words. For example, the syllable “re-” as in “rewrite” or “repay” means “to do again,” and the suffix “-est” as in “happiest” or “coolest” means “to the maximum.”

Semantics: Semantics refers to the set of rules we use to obtain meaning from morphemes. For example, adding “ed” to the end of a verb makes it past tense.

Syntax: Syntax is the set of rules by which we construct sentences. Each language has a different syntax. The syntax of the English language requires that each sentence have a noun and a verb, each of which may be modified by adjectives and adverbs. Some syntaxes make use of the order in which words appear. For example, in English, “The man bites the dog” is different from “The dog bites the man.”

Pragmatics: The social side of language is expressed through pragmatics, or how we communicate effectively and appropriately with others. Examples of pragmatics include turn-taking, staying on topic, volume, and tone of voice, and appropriate eye contact.

Lastly, words do not possess fixed meanings but change their interpretation as a function of the context in which they are spoken. We use contextual information, the information surrounding language, to help us interpret it. Examples of contextual information include our knowledge and nonverbal expressions such as facial expressions, postures, and gestures. Misunderstandings can easily arise if people are not attentive to contextual information or if some of it is missing, such as in newspaper headlines or text messages.

Progression of Infant Communication

Language acquisition is an important aspect of cognitive development. The order in which children learn language structures is consistent across children and cultures (Hatch, 1993). Babies begin to develop language and communication skills before birth.

Do newborns communicate? Of course, they do. However, they do not communicate using oral language. Instead, they communicate their thoughts and needs with body posture (being relaxed or still), gestures, cries, and facial expressions. A person who spends adequate time with an infant can learn which cries indicate pain and which ones indicate hunger, discomfort, or frustration.

Intentional Vocalizations

In terms of producing spoken language, babies begin to coo almost immediately. Cooing is a one-syllable combination of a consonant and a vowel sound (e.g., coo or ba). Interestingly, babies replicate sounds from their own languages. A baby whose parents speak French will coo in a different tone than a baby whose parents speak Spanish or Urdu. These gurgling, musical vocalizations can serve as a source of entertainment to an infant who has been laid down for a nap or seated in a carrier on a car ride. Cooing serves as practice for vocalization, as well as the infant hears the sound of his or her own voice and tries to repeat sounds that are entertaining. Infants also begin to learn the pace and pause of conversation as they alternate their vocalization with that of someone else and then take their turn again when the other person’s vocalization has stopped.

At about four to six months of age, infants begin making even more elaborate vocalizations that include the sounds required for any language. Guttural sounds, clicks, consonants, and vowel sounds stand ready to equip the child with the ability to repeat whatever sounds are characteristic of the language heard. Eventually, these sounds will no longer be used as the infant grows more accustomed to a particular language.

Babbling and Gesturing

At about 7 months, infants begin babbling, engaging in intentional vocalizations that lack specific meaning and comprise a consonant-vowel repeated sequence, such as ma-ma-ma, da-da-da. Children babble as practice in creating specific sounds, and by the time they are 1 year old, the babbling uses primarily the sounds of the language that they are learning (de Boysson-Bardies et al., 1984). These vocalizations have a conversational tone that sounds meaningful even though it isn’t. Babbling also helps children understand the social and communicative functions of language. Children who are exposed to sign language babble in sign by making hand movements that represent real language (Petitto & Marentette, 1991).

Gesturing: Children communicate information through gesturing long before they speak, and there is some evidence that gesture usage predicts subsequent language development (Verson & Goldin-Meadow, 2005). Deaf babies also use gestures to communicate wants, reactions, and feelings. Because gesturing seems to be easier than vocalization for some toddlers, sign language is sometimes taught to enhance one’s ability to communicate by making use of the ease of gesturing. The rhythm and pattern of language are used when deaf babies sign, just as it is when hearing babies babble.

Understanding

At around ten months of age, infants can understand more than they can say, which is referred to as receptive language. You may have experienced this phenomenon as well if you have ever tried to learn a second language. You may have been able to follow a conversation more easily than contribute to it. One of the first words that children understand is their own name, usually by about 6 months, followed by commonly used words like “bottle,” “mama,” and “doggie” by 10 to 12 months (Mandel et al., 1995).

Infants shake their head “no” around 6–9 months, and they respond to verbal requests to do things like “wave bye-bye” or “blow a kiss” around 9–12 months. Children also use contextual information, particularly the cues that parents provide, to help them learn language. Children learn that people are usually referring to things that they are looking at when they are speaking (Baldwin, 1993) and that the speaker’s emotional expressions are related to the content of their speech.

Holophrastic Speech

Children begin using their first words at about 12 or 13 months of age and may use partial words to convey thoughts at even younger ages. These one-word expressions are referred to as holophrastic speech. For example, the child may say “ju” for the word “juice” and use this sound when referring to a bottle. The listener must interpret the meaning of the holophrase, and when this is someone who has spent time with the child, interpretation is not too difficult. But, someone who has not been around the child will have trouble knowing what is meant. Imagine the parent who, to a friend, exclaims, “Ezra’s talking all the time now!” The friend hears only “ju da ga,” to which the parent explains, “I want some milk when I go with Daddy.”

Language Errors

The early utterances of children contain many errors, for instance, confusing /b/ and /d/, or /c/ and /z/. The words children create are often simplified, in part because they are not yet able to make the more complex sounds of the real language (Dobrich & Scarborough, 1992). Phonological characteristics of words young children try to say. Journal of Child Language, 19(3), 597–616.[/footnote]. Children may say “keekee” for kitty, “nana” for banana, and “vesketti” for spaghetti because it is easier. Often, these early words are accompanied by gestures that may also be easier to produce than the words themselves. Children’s pronunciations become increasingly accurate between 1 and 3 years, but some problems may persist until school age.

A child who learns that a word stands for an object may initially think that the word can be used for only that particular object, which is referred to as underextension. Only the family’s Irish Setter is a “doggie”, for example. More often, however, a child may think that a label applies to all objects that are similar to the original object, which is called overextension. For example, all animals become “doggies”.

First Words and Cultural Influences

First words, if the child is using English, tend to be nouns. The child labels objects such as cup, ball, or other items that they regularly interact with. In a verb-friendly language such as Chinese, however, children may learn more verbs. This may also be due to the different emphasis given to objects based on culture. Chinese children may be taught to notice actions and relationships between objects, while children from the United States may be taught to name an object and its qualities (color, texture, size, etc.). These differences can be seen when comparing interpretations of art by older students from China and the United States.

Vocabulary growth spurt

One-year-olds typically have a vocabulary of about 50 words. But by the time they become toddlers, they have a vocabulary of about 200 words and begin putting those words together in telegraphic speech (short phrases). This language growth spurt is called the naming explosion because many early words are nouns (persons, places, or things).

Two-word sentences and telegraphic (Text Message) speech

Words needed to convey messages are used, but the articles and other parts of speech necessary for grammatical correctness are not yet used. These expressions sound like a telegraph, or perhaps a better analogy today would be that they read like a text message. Telegraphic speech/text message speech occurs when unnecessary words are not used, typically thought of as using only two words together. “Give ball” is used rather than “Give the baby the ball.”

Infant-directed Speech

Have you ever wondered why adults tend to use that sing-song type of intonation and exaggeration when talking to children? This represents a universal tendency and is known as infant-directed speech. It involves exaggerating the vowel and consonant sounds, using a high-pitched voice, and delivering the phrase with great facial expression (Clark, 2009). Why is this done? Infants are frequently more attuned to the tone of voice of the person speaking than to the content of the words themselves and are aware of the target of speech.

Theories of Language Development

How is language learned? Each major theory of language development emphasizes different aspects of language learning: that infants’ brains are genetically attuned to language, that infants must be taught, and that infants’ social impulses foster language learning.

Psychological theories of language learning differ in terms of the importance they place on nature and nurture. Remember that we are a product of both nature and nurture. Researchers now believe that language acquisition is partially inborn and partially learned through our interactions with our linguistic environment (Gleitman & Newport, 1995; Stork & Widdowson, 1974).

The first two theories of language development represent two extremes in the level of interaction required for language to occur (Berk, 2007).

Learning Theory: Skinner and Bandura

Perhaps the most straightforward explanation of language development is that it occurs through the principles of learning, including association and reinforcement (Skinner, 1953). Additionally, Bandura (1977) described the importance of observation and imitation of others in learning language. There must be at least some truth to the idea that language is learned through environmental interactions or nurture. Children learn the language that they hear spoken around them rather than some other language. Also supporting this idea is the gradual improvement of language skills with time. It seems that children modify their language through imitation and reinforcement, such as parental praise and being understood. For example, when a two-year-old child asks for juice, he might say, “me juice,” to which his mother might respond by giving him a cup of apple juice.

Critique of Learning Theory: However, language cannot be entirely learned. For one, children learn words too fast for them to be learned through reinforcement. Between the ages of 18 months and 5 years, children learn up to 10 new words every day (Anglin, 1993). More importantly, language is more generative than it is imitative. Language is not a predefined set of ideas and sentences that we choose when we need them but rather a system of rules and procedures that allows us to create an infinite number of statements, thoughts, and ideas, including those that have never previously occurred. When a child says that she “swimmed” in the pool, for instance, she is showing generativity because it easily generated from the normal system of producing language.

Other evidence that refutes the idea that all language is learned through experience comes from the observation that children may learn languages better than they ever hear them. Children who are deaf and whose parents do not speak American Sign Language very well are nevertheless able to learn it perfectly on their own and may even make up their own language if they need to (Goldin-Meadow & Mylander, 1998). A group of children who could not hear in a school in Nicaragua, whose teachers could not sign, invented a way to communicate through made-up signs (Senghas et al., 2005). The development of this new Nicaraguan Sign Language has continued and changed as new generations of students have come to the school and started using the language. Although the original system was not a real language, it is becoming closer and closer every year, showing the development of a new language in modern times.

Chomsky and the Language Acquisition Device

Chomsky and Nativism: The linguist Noam Chomsky is a believer in the nature approach to language, arguing that human brains contain a language acquisition device that includes a universal grammar that underlies all human language (Chomsky, 1965). According to this approach, each of the many languages spoken around the world (there are between 6,000 and 8,000) is an individual example of the same underlying set of procedures that are hardwired into human brains. Chomsky’s account proposes that children are born with a knowledge of general rules of syntax that determine how sentences are constructed. Language develops as long as the infant is exposed to it. No teaching, training, or reinforcement is required for language to develop as proposed by Skinner.

Social pragmatics

Another language theory emphasizes the child’s active engagement in learning the language out of a need to communicate. Social impulses foster infant language because humans are social beings, and we must communicate because we are dependent on each other for survival. The child seeks information, memorizes terms, imitates the speech heard from others, and learns to conceptualize using words as language is acquired. Tomasello and Herrmann (2010) argue that all human infants, as opposed to chimpanzees, seek to master words and grammar in order to join the social world. Many would argue that all three of these theories (Chomsky’s argument for nativism, conditioning, and social pragmatics) are important for fostering the acquisition of language (Berger, 2004).

Moral Reasoning in Infants

The Foundation of Moral Reasoning in Infants

The work of Lawrence Kohlberg was an important start to modern research on moral development and reasoning. However, Kohlberg relied on a specific method: he presented moral dilemmas and asked children and adults to explain what they would do and—more importantly—why they would act in that particular way. Kohlberg found that children tended to make choices based on avoiding punishment and gaining praise. However, children are at a disadvantage compared to adults when they must rely on language to convey their inner thoughts and emotional reactions, so what they say may not adequately capture the complexity of their thinking.

Starting in the 1980s, developmental psychologists created new methods for studying the thought processes of children and infants long before they acquired language. One particularly effective method is to present children with puppet shows to grab their attention and then record nonverbal behaviors, such as looking and choosing, to identify children’s preferences or interests.

For much of the past decade, a research group at Yale University has been using puppet shows to study children’s moral thinking. What they have discovered has given us a glimpse of surprisingly complex thought processes that may serve as the foundation of moral reasoning.

Remember that Lawrence Kohlberg thought that children at this age—and, in fact, through 9 years of age—are primarily motivated to avoid punishment and seek rewards. Neither Kohlberg nor Carol Gilligan nor Jean Piaget was likely to predict that infants as young as 3 months would show preferences for moral behavior.

Check out this video from 60 Minutes with a look inside the Yale Baby Lab.

Attribution

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

References

Anglin, J. M. (1993). Vocabulary development: A morphological analysis. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 58(10), v–165.

Baldwin, D. A. (1993). Early referential understanding: Infants’ ability to recognize referential acts for what they are. Developmental Psychology, 29(5), 832–843.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Blossom, M. & Morgan, J. L. (2006). Does the face say what the mouth says? A study of infants’ sensitivity to visual prosody. In the 30th annual Boston University Conference on Language Development, Somerville, MA.

Campanella, J., & Rovee-Collier, C. (2005). Latent learning and deferred imitation at 3 months. Infancy, 7(3), 243-262.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1972). Language and mind. NY: Harcourt Brace.

Clark, E. V. (2009). What shapes children’s language? Child-directed speech and the process of acquisition. In V. C. M. Gathercole (Ed.), Routes to language: Essays in honor of Melissa Bowerman. NY: Psychology Press.

de Boysson-Bardies, B., Sagart, L., & Durand, C. (1984). Discernible differences in the babbling of infants according to target language. Journal of Child Language, 11(1), 1–15.

Dobrich, W., & Scarborough, H. S. (1992). Phonological characteristics of words young children try to say. Journal of Child Language, 19(3), 597–616.

Fernández, E. & Cairns, H.. (2010). Fundamentals of psycholinguistics. Wiley & Sons

Giles, A., & Rovee-Collier, C. (2011). Infant long-term memory for associations formed during mere exposure. Infant Behavior and Development, 34(2), 327-338.

Gleitman, L. R., & Newport, E. L. (1995). The invention of language by children: Environmental and biological influences on the acquisition of language. An invitation to cognitive science, 1, 1-24.

Goldin-Meadow, S., & Mylander, C. (1998). Spontaneous sign systems created by deaf children in two cultures. Nature, 391(6664), 279–281.

Hatch, E. M. (1983). Psycholinguistics: A second language perspective. Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers.

Johnson, S., & Newport, E. L. (1989). Critical period effects in second language learning: The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cognitive Psychology, 21, 60–99.

Klein, P. J., & Meltzoff, A. N. (1999). Long-term memory, forgetting, and deferred imitation in 12-month-old infants. Developmental Science, 2(1), 102-113.

Lenneberg, E. (1967). Biological foundations of language. Wiley.

Mandel, D. R., Jusczyk, P. W., & Pisoni, D. B. (1995). Infants’ recognition of the sound patterns of their own names. Psychological Science, 6(5), 314–317.

Petitto, L. A., & Marentette, P. F. (1991). Babbling in the manual mode: Evidence for the ontogeny of language. Science, 251(5000), 1493–1496.

Piaget, J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child. New York: Basic Books.

Pickens, J. (1994). Full-term and preterm infants’ perception of face-voice synchrony. Infant Behavior and Development, 17, 447–455.

Rovee-Collier, C. (1987). Learning and memory in infancy. In J. D. Osofsky (Ed.), Handbook of infant development, (2nd, ed., pp.98-148). New York: Wiley.

Rovee-Collier, C., & Hayne, H. (1987). Reactivation of infant memory: Implications for cognitive development. In H. W. Reese (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior. (Vol. 20, pp. 185-238). London, UK: Academic Press.

Rovee-Collier, C. (1990). The “memory system” of prelinguistic infants. Annuals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 608, 517-542. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-66231990.tb48908.

Rymer, R. (1993). Genie: A scientific tragedy. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Senghas, R. J., Senghas, A., & Pyers, J. E. (2005). The emergence of Nicaraguan Sign Language: Questions of development, acquisition, and evolution. In S. T. Parker, J. Langer, & C. Milbrath (Eds.), Biology and knowledge revisited: From neurogenesis to psychogenesis (pp. 287–306). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Singleton. M. (1995). Introduction: A critical look at the critical period hypothesis in second language acquisition research. In D.M. Singleton & Z Lengyel (Eds.), The age factor in second language acquisition: A critical look at the critical period hypothesis in second language acquisition research (pp. 1–29). Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. NY: Free Press.

Spelke, E. S., & Cortelyou, A. (1981). Perceptual aspects of social knowing: Looking and listening in infancy. In M.E. Lamb & L.R. Sherrod (Eds.), Infant social cognition: Empirical and theoretical considerations (pp. 61–83). Erlbaum.

Stork, F. & Widdowson, J. (1974). Learning About Linguistics. London: Hutchinson.

Verson, J. M., & Goldin-Meadow, S. (2005). Gesture paves the way for language development. Psychological science, 16(5), 367-371.

Werker, J. F., & Tees, R. C. (2002). Cross-language speech perception: Evidence for perceptual reorganization during the first year of life. Infant Behavior and Development, 25, 121-133.