Section 7: Middle to Late Childhood

7.1 Physical Development in Middle to Late Childhood

What’s physical development like during middle childhood?

Children enter middle childhood, still looking very young, and end the stage on the cusp of adolescence. Most children have gone through a growth spurt that makes them look rather grown-up. The obvious physical changes are accompanied by changes in the brain. While we don’t see the actual brain changing, we can see the effects of the brain changes in the way that children in middle childhood play sports, write, and play games.

- Describe physical growth during middle childhood.

- Prepare recommendations to avoid health risks in school-aged children.

- Describe the six types of play that emerge over time.

- Define pretend play and describe how it contributes to development.

- Describe the ways that children benefit from play.

- Describe development of gender identity and sexuality in middle adulthood

Middle and late childhood

Middle and late childhood spans the ages between early childhood and adolescence, approximately ages 6 to 11. Children gain greater control over the movement of their bodies, mastering many gross and fine motor skills that eluded the younger child. Changes in the brain during this age enable not only physical development but also contribute to greater reasoning and flexibility of thought. School becomes a big part of middle and late childhood, and it expands their world beyond the boundaries of their own family. Peers start to take center stage, often prompting changes in the parent-child relationship. Peer acceptance also influences children’s perception of self and may have consequences for emotional development beyond these years.

Overall Physical Growth

Rates of growth generally slow during these years. Typically, a child will gain about 4-6 pounds a year and grow about 2-3 inches yearly (Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2022). They also tend to slim down and gain muscle strength and lung capacity making it possible to engage in strenuous physical activity for long periods of time. The beginning of the growth spurt, which occurs prior to puberty, tends to begin two years earlier for females than males. In the U.S., the mean age for the beginning of growth spurts for females is nine, while for males it is eleven. Children of this age tend to sharpen their abilities to perform both gross motor skills, such as riding a bike, and fine motor skills, such as cutting their fingernails. In gross motor skills (involving large muscles) males typically outperform females, while females tend outperform males in fine motor skills (small muscles). These improvements in motor skills are related to brain growth and experience during this developmental period.

Losing Primary Teeth

Deciduous teeth, commonly known as milk teeth, baby teeth, primary teeth, and temporary teeth, are the first set of teeth in the growth development of humans. The primary teeth are important for the development of the mouth, the development of the child’s speech, the child’s smile, and play a role in chewing food. Most children lose their first tooth around age 6 and then continue to lose teeth for the next 6 years. In general, children lose the teeth in the middle of the mouth first and then lose the teeth next to those in sequence over the 6-year span. By age 12, generally, all of the teeth are permanent teeth; however, it is not extremely rare for one or more primary teeth to be retained beyond this age, sometimes well into adulthood, often because the secondary tooth fails to develop.

Brain Growth

Two major brain growth spurts occur during middle/late childhood (Spreen et al., 1995). Between ages 6 and 8, significant improvements in fine motor skills and eye-hand coordination are noted. Then, between 10 and 12 years of age, the frontal lobes become more developed, and improvements in logic, planning, and memory are evident (van der Molen & Molenaar, 1994). Myelination is one factor responsible for these growths. From age 6 to 12, the nerve cells in the association areas of the brain, that is, those areas where sensory, motor, and intellectual functioning connect, become almost completely myelinated (Johnson, 2005). This myelination contributes to increases in information processing speed and reaction time. The hippocampus, responsible for transferring information from short-term to long-term memory, also shows increases in myelination, resulting in improvements in memory functioning (Rolls, 2000). Children in middle to late childhood are also better able to plan and coordinate activity using both the left and right hemispheres of the brain and control emotional outbursts. Paying attention is also typically improved as the prefrontal cortex matures (Markant & Thomas, 2013).

The Role of Play in Development

What is Play?

Play is a spontaneous, fun activity found at all ages and in all cultures. Play begins in infancy. Freud analyzed play in terms of emotional development. Vygotsky and Piaget saw play as a way for children to develop their intellectual abilities (Dyer & Moneta, 2006). Piaget called play “a child’s work.” Subsequent research has shown that play provides many positive outcomes for children in all domains of development. The activity of play provides children with opportunities to exercise all their developing capacities: physical, cognitive, emotional, and social. Play is spontaneous; children are intrinsically motivated to play. Play may be done alone or with others. It often involves pretending and make-believe.

Types of Play

In a classic study, Parten (1932) observed two to five-year-old children and noted six types of play: Three labeled as non-social play (unoccupied, solitary, and onlooker) and three categorized as social play (parallel, associative, and cooperative). The following Table describes each type of play. Younger children engage in non-social play more than older children; by age five, associative and cooperative play are the most common forms of play (Dyer & Moneta, 2006).

Table 1 Parten’s Classification of Types of Play in Preschool Children

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Unoccupied Play | Children’s behavior seems more random and without a specific goal. This is the least common form of play. |

| Solitary Play | Children play by themselves, do not interact with others, nor are they engaging in similar activities as the children around them. |

| Onlooker Play | Children are observing other children playing. They may comment on the activities and even make suggestions, but will not directly join the play. |

| Parallel Play | Children play alongside each other, using similar toys, but do not directly act with each other. |

| Associative Play | Children will interact with each other and share toys, but are not working toward a common goal. |

| Cooperative Play | Children are interacting to achieve a common goal. Children may take on different tasks to reach that goal. |

adapted from Paris, Ricardo, & Rymond, 2019

Pretend Play. Pretense is a familiar characteristic of play. Pretend play can be combined with physical play or playing with objects. When pretending, children act as-if; they engage in make-believe. Their words and actions are not literal but evoke something beyond what is concretely present (Lillard, Lerner, Hopkins, Dore, Smith, and Palmquist, 2015). In his study of cognitive development, Piaget was interested in pretend play, and he documented the way in which it involved symbolic thought, that is, the ability to have a symbol represent something in the real world. A toy, for example, has qualities beyond the way it was designed to function, and can be used to stand for a character or a completely different object. A banana can be used as a telephone. As seen in the study of early childhood, symbolic thought is an important capability developed at the end of the sensorimotor stage that paves the way for the development of language. But pretend play uses capabilities that go beyond symbolic thought and mental representation.

Pretend play also requires the use of fantasy and imagination (Sobel & Lillard, 2001). Imagination is distinct from but jointly engaged during play with executive function, including the developing capabilities of memory, inhibition, and attention shifting (Carlson & White, 2013). A complex form of pretend play emerges in Parten’s last two stages: associative play and cooperative play. This new form is sociodramatic play, which is make-believe play with others, involving objects and actions woven into some kind of imagined situation or story. It is often scaffolded in play with adults or older children. As the development of sociodramatic play progresses, children begin acting out roles. They use situated imaginary identities as the basis of action and to create storylines. Through the creation of settings, roles, and narrative, imagination is used to explore ideas about what follows what and about how things unfold in the world (Deunk, Berenst, & De Glopper, 2008). Perspective-taking is improved through this social form of pretend play. Emotional development is also fostered by sociodramatic play, as children choose imagined interpretations and responses to imagined emotions in pretend situations and respond to emotions that arise in actual conflict generated between playmates. Perspective-taking and dealing with emotions during pretend play contribute to the development of self-regulation (Gioia & Tobin, 2020).

Benefits of Play

“Play in all its rich variety is one of the highest achievements of the human species,” says Dr. David Whitebread from Cambridge University’s Faculty of Education. “It underpins how we develop as intellectual, problem-solving, emotional adults and is crucial to our success as a highly adaptable species.” International bodies like the United Nations and the European Union have begun to develop policies concerned with children’s right to play, and to consider implications for leisure facilities and educational programs.

Thanks to the Centre for Research on Play in Education, Development and Learning (PEDaL) at Cambridge, Whitebread, Baker, Gibson and a team of researchers are accumulating evidence on the role played by play in how a child develops. “A strong possibility is that play supports the early development of children’s self-control,” explains Baker, “. . . our abilities to develop awareness of our own thinking processes.” If playful experiences do facilitate this aspect of development, say the researchers, it could be extremely significant for educational practices because the ability to self-regulate has been shown to be a key predictor of academic performance.

Gibson adds: “Playful behaviour is also an important indicator of healthy social and emotional development. In my previous research, I investigated how observing children at play can give us important clues about their well-being and can even be useful in the diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders like autism.”

Source: Plays the Thing, Cambridge University https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/features/plays-the-thing is licensed under a CC BY 4.0

Sports and Physical Education

Middle childhood seems to be a great time to introduce children to organized sports, and in fact, many parents do. Nearly 3 million children play soccer in the United States (United States Youth Soccer, 2012). This activity promises to help children improve athletically, learn a sense of competition, and build social skills. However, it has been suggested that the emphasis on competition and athletic skill can be counterproductive and lead children to grow tired of the game and want to quit. In many respects, it appears that children’s activities are no longer children’s activities once adults become involved and approach the games as adults rather than children. The U. S. Soccer Federation recently advised coaches to reduce the amount of drilling engaged in during practice and to allow children to play more freely and to choose their own positions. The hope is that this will build on their love of the game and foster their natural talents.

Sports are important for children. According to research done by the Aspen Institue (2022), participation in sports has been linked to:

- Higher levels of satisfaction with family and overall quality of life in children

- Improved physical and emotional development, including lower stress, anxiety, and depression

- Better academic performance and creativity

- Lower risk of adult illness, including heart disease, cancer, stroke, and diabetes.

Yet, a study on children’s sports in the United States (Sabo & Veliz, 2008) has found that gender, poverty, location, ethnicity, and disability can limit opportunities to engage in sports. Girls were more likely to have never participated in any type of sport. They also found that fathers may not be providing their daughters as much support as they do their sons. While boys rated their fathers as their biggest mentors who taught them the most about sports, girls rated coaches and physical education teachers as their key mentors. Sabo and Veliz (2008) also found that children in suburban neighborhoods participated much more in sports than boys and girls living in rural or urban centers. In addition, Caucasian girls and boys participated in organized sports at higher rates than minority children.

The Youth Sports Industrial Complex?

A 2019 analysis estimated the youth sports industry was worth $19.2 billion; for context, the most profitable professional league, the NFL, was worth an estimated $15 billion (Ryssdal & McHenry, 2022). The cost of participating in youth sports, from league fees and equipment to tournaments and travel, has increased dramatically and has become inaccessible for many families. For some sports, average annual costs are over $1,000 – and can balloon well into five figures. The Aspen Institute (2022) estimated U.S. families spend $30 to $40 billion annually on their children’s sports activities. This is based on Aspen’s analysis of parent surveys and national sport participation data. That’s more than the annual revenues of any professional league.

Travel is now the costliest feature in youth sports. On average, across all sports, parents spent more annually on travel ($260 per sport per child) than equipment ($154), private lessons ($183), registration fees ($168), and camps ($111). That average includes all kids playing sports, not just those on travel teams, which often start in grade school and can cost families far more than a couple hundred dollars a year (The Aspen Institute Project Play, 2022). Many families are spending quite a lot more than these figures, especially for year-round travel teams and tournaments, individual training, tournament fees and related expenses, equipment/uniforms, and sports medicine/rehabilitation. Girls’ volleyball can be $3000 – $6000 upfront per season just for team participation. This does not include personal travel expenses, fundraising for coaching travel and expenses, entrance fees, etc. (Ounjian, personal communication).

State of Play Oakland (2022) shows a divide based on race, gender, and income in youth sports experiences for some children in Oakland. Among the report’s findings:

-

Oakland girls (9%) are less likely to be sufficiently physically active than boys (19%).

-

Access to quality parks and teams is unevenly distributed based on race and ethnicity.

-

White children are three times more likely than Latino/a/x youth and two times more likely than Black and Asian kids to play sports on a recreation center team.

-

Although Oakland is largely viewed as a football and basketball town, youth said they are very interested in trying other sports. However, children lack sustainable ways to keep playing these new sports to establish healthy habits for life.

Data on other historically marginalized groups, such as Native-American children, are not even reported in government-funded studies that track physical activity in youth (University of Florida’s SPARC, 2014).

Learn more about Project Play Oakland and other cities nationwide: https://projectplay.org/

Quitting Sports

Students don’t always persist in their participation in extracurricular and other organized sports activities. Sabo and Veliz (2008) asked children who had dropped out of organized sports why they left. For both girls and boys, the number one answer was that it was no longer any fun. According to the Sports Policy and Research Collaborative (SPARC) (2013), almost 1 in 3 children drop out of organized sports, and while there are many factors involved in the decision to drop out, one suggestion has been the lack of training that coaches of children’s sports receive may be contributing to this attrition (Barnett, Smoll & Smith, 1992). Several studies have found that when coaches receive proper training, the drop-out rate is about 5% instead of the usual 30% (Fraser-Thomas, Côté, & Deakin, 2005; SPARC, 2013).

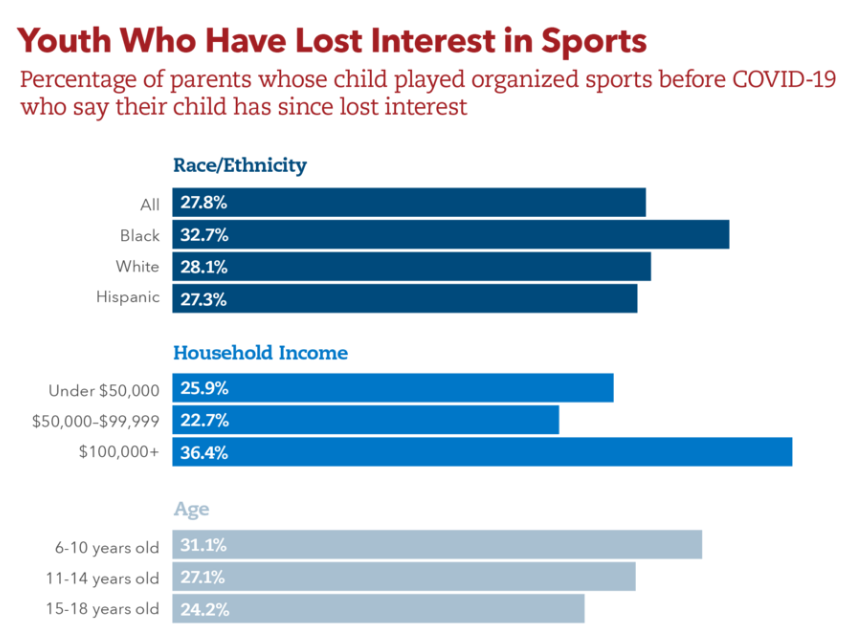

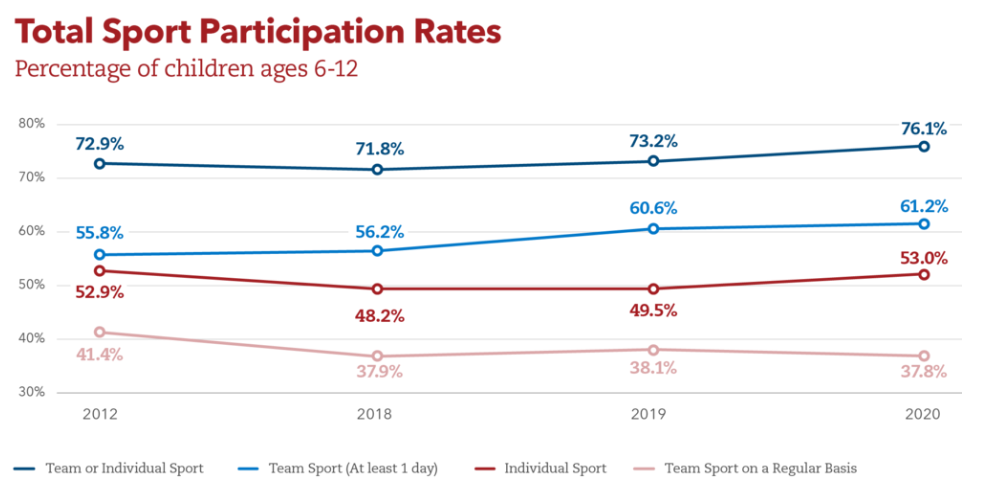

Many youths lost interest in sports even before the COVID-19 pandemic. Figure 7 denotes disparities among children who have lost interest in sports. We also notice in Figure 8 that there is a decrease in the total sports participation rates in regard to team sports on a regular basis. (The Aspen Institute Project Play, 2021).

Physical Education

For many children, physical education in school is a key component in introducing children to sports and regular physical activity. After years of schools cutting back on physical education programs, there has been a turnaround prompted by concerns over childhood obesity and related health issues. Despite these changes, currently, only the state of Oregon and the District of Columbia meet PE guidelines of a minimum of 150 minutes per week of physical activity in elementary school and 225 minutes in middle school (SPARC, 2016). There is also controversy about physical education. Some experts recommend changing the content of these classes. Training in competitive sports, often a high priority, is unlikely to reach the least physically fit youngsters. Instead, programs could emphasize cooperation, enjoyable informal games, and individual exercise.

Welcome to the world of e-sports

The recent Sport Policy and Research Collaborative (SPARC) (Sport Policy and Research Collaborative, 2016) report on the “State of Play” in the United States highlights a disturbing trend. One in four children between the ages of 5 and 16 rate playing computer games with their friends as a form of exercise. In addition, e-sports, which, as SPARC writes, is about as much a sport as poker, involves children watching other children play video games.

Since 2008, there has also been a downward trend in the number of sports children are engaged in, despite a body of research evidence that suggests specializing in only one activity can increase the chances of injury, while playing multiple sports can be more protective (Sport Policy and Research Collaborative, 2016). A University of Wisconsin study found that 49% of athletes who specialized in a sport experienced an injury compared with 23% of those who played multiple sports (McGuine, 2016).

Video example

This video gives a brief history of the significance of jump rope, particularly for Black girls in the U.S.

What is “kinetic orality,” according to the video?

What is the importance of double dutch to African American girl’s sports?

Additional resources: This is double dutch (video). The Fantastic Four, four junior high school girls from the Lower Eastside of Manhattan, won the World Wide Double Dutch Championship in 1979. We talked to them almost 40 years later about the sport and their legacy.

The Games Black Girls Play (2006) by Kyra D. Gaunt

Health Risks: Childhood Obesity

In the U.S., nearly 20 percent of school-aged American children are obese, which is defined as being in the 95% or above in body weight (CDC, 2021). The percentage of obesity in school-aged children has increased substantially since the 1960s. Obesity is multifactorial: it’s influenced by many different factors, such as genetics, metabolism, eating and activity behaviors, community and neighborhood design and safety, sleep, and childhood events. Kids gained weight faster during the COVID-19 pandemic. The rise in childhood obesity is attributed to the introduction of a steady diet of television and other sedentary activities along with high-fat, fast foods as a culture. Pizza, hamburgers, chicken nuggets, and “Lunchables” with soda have replaced more nutritious foods as staples.

One consequence of childhood obesity is that children who are overweight tend to be ridiculed and teased by others. This can certainly be damaging to their self-image and popularity. In addition, obese children run the risk of suffering orthopedic problems such as knee injuries and an increased risk of heart disease and stroke in adulthood. It may be difficult for a child who is obese to become a non-obese adult. In addition, the number of cases of pediatric diabetes has risen dramatically in recent years.

Dieting is not really the solution to childhood obesity. If you diet, your basal metabolic rate tends to decrease, thereby making the body burn even fewer calories in order to maintain its weight. Increased activity is much more effective in lowering weight and improving the child’s health and psychological well-being. Exercise reduces stress, and being an overweight child, subjected to the ridicule of others, can certainly be stressful. Parents should take caution against emphasizing diet alone to avoid the development of any obsession with dieting that can lead to eating disorders as teens. Again, increasing a child’s activity level is most helpful.

Behavioral interventions, including training children to overcome impulsive behavior, are being researched to help curtail childhood obesity (Lu, 2016). Practicing inhibition has been shown to strengthen the ability to resist unhealthy foods. Caregivers can help children the best when they are warm and supportive without using shame or guilt. Caregivers can also act like the child’s frontal lobe until it is developed by helping them make correct food choices and praising their efforts (Liang et al., 2014).

Gender and Sexual Development

Once children enter grade school (approximately ages 7–12), their awareness of social rules increases, and they may become more modest and want more privacy, particularly around adults. Curiosity about adult sexual behavior also tends to increase—particularly as puberty approaches—and children may begin to seek out sexual content in television, movies, the internet, and printed material. Children approaching puberty may also start displaying romantic and sexual interest in their peers.

For gender-nonconforming children or transgender children, early/middle childhood is an age where the psychological costs of society’s gender boxes and lines can become apparent. At this age, children can start to sense (or clearly know) that they have been permanently assigned to a biological sex that comes with a narrow gender expression or an eventually gendered body whose physicality is not consonant with their own internal needs or identity. If so, then confusion or (more or less strong) feelings of gender dissonance may emerge. In the clinical literature, these feelings are sometimes labeled “gender dysphoria” to indicate the sadness and desperation that children may feel when they realize that they have been permanently assigned to the “wrong” gender expression, gender identity, and/or biological sex.

A major developmental milestone for gender identification takes place during middle childhood, sometimes referred to as the “latency” stage or phase, and loosely modeled after Freud’s description of children’s psychosexual stages. During this period (about ages 8 or 9 until puberty), children seem to be less active in working out issues explicitly connected to gender or sexual identity. In general, children seem to be more mellow or laid back about the whole “gender thing,” largely recognizing that scripts about gender-appropriate signifiers (like colors, behaviors, or activities) are societal conventions and not true moral issues. At this age, children seem to relax their enforcement of gender rules, and the “yuckiness” of the opposite sex begins to fade. Many gender variant children, during this period, also seem to relax, maybe deciding that non-conformity is more trouble than it is worth, and so (at least temporarily) adopting conventional signifiers that are more aligned with their biological sex.

For parents who are worried about the effects of hetero-normative gender stereotypes, it can feel like your child has made it safely through the gender curriculum and come out whole on the other side. For parents who are worried about their gender-nonconforming children, it can also feel like the “problem” has been solved, and it was (after all) just a phase.

The next major milestone in gender development is ushered in by puberty, which usually starts between ages 10-12 for girls and between ages 12-14 for boys. The reality of biological changes in both primary and secondary sexual characteristics seems to trigger a major shift, not only in children’s neurophysiology but also in their psychological systems and social relationships. When puberty strikes, the issue of what it means to be male and female in this historical moment seems to come to center stage, and teenagers in middle school and early high school seem to be trying to enact and rigidly enforce all of society’s current stereotypes about gender. This process is called “gender intensification,” and it will be more or less “intense” depending on the local culture, their stereotypes, and the rigidity with which they are viewed.

Development of Sexual Orientation

According to current scientific understanding, individuals are usually aware of their sexual orientation between middle childhood and early adolescence. However, this is not always the case, and some do not become aware of their sexual orientation until much later in life. It is not necessary to participate in sexual activity to be aware of these emotional, romantic, and physical attractions; people can be celibate and still recognize their sexual orientation. Some researchers argue that sexual orientation is not static and inborn but is instead fluid and changeable throughout the lifespan.

There is no scientific consensus regarding the exact reasons why an individual holds a particular sexual orientation. Research has examined possible biological, developmental, social, and cultural influences on sexual orientation, but there has been no evidence that links sexual orientation to only one factor (APA, 2016). However, evidence for biological explanations, including genetics, birth order, and hormones, will be summarized since many scientists argue that biological processes occurring during the embryonic and early postnatal life play the central organizing role in sexual orientation (Balthazart, 2018).

Genetics. Using both twin and familial studies, heredity provides one biological explanation for same-sex orientation. Bailey and Pillard (1991) studied pairs of male twins and found that the concordance rate for identical twins was 52%, while the rate for fraternal twins was only 22%. Bailey et al. (1993) studied female twins and found a similar difference with a concordance rate of 48% for identical twins and 16% for fraternal twins. Schwartz, Kim, Kolundzija, Rieger, & Sanders (2010) found that gay men had more gay male relatives than straight men, and sisters of gay men were more likely to be lesbians than sisters of straight men.

Fraternal Birth Order. The fraternal birth order effect indicates that the probability of a boy identifying as gay increases for each older brother born to the same mother (Balthazart, 2018; Blanchard, 2001). According to Bogaret et al. “the increased incidence of homosexuality in males with older brothers results from a progressive immunization of the mother against a male-specific cell-adhesion protein that plays a key role in cell-cell interactions, specifically in the process of synapse formation” (as cited in Balthazart, 2018, p. 234). A meta-analysis indicated that the fraternal birth order effect explains the sexual orientation of between 15% and 29% of gay men.

Hormones. Excess or deficient exposure to hormones during prenatal development has also been theorized as an explanation for sexual orientation. One-third of females exposed to abnormal amounts of prenatal androgens, a condition called congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), identify as bisexual or lesbian (Cohen-Bendahan, van de Beek, & Berenbaum, 2005). In contrast, too little exposure to prenatal androgens may affect male sexual orientation by not masculinizing the male brain (Carlson, 2011).

Attributions

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

“Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0

Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

References

Bailey, J. M., Pillard, R. C., Neale, M. C. & Agyei, Y. (1993). Heritable factors influence sexual orientation in women. Archives of General Psychology, 50, 217-223.

Balthazart, J. (2018). Fraternal birth order effect on sexual orientation explained. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(2), 234-236.

Barnett, N. P., Smoll, F. L., & Smith, R. E. (1992). Effects of enhancing coach-athlete relationships on youth sport attrition. The Sport Psychologist, 6, 111-127.

Blanchard, R. (2001). Fraternal birth order and the maternal immune hypothesis of male homosexuality. Hormones and Behavior, 40, 105-114.

Boulton, M. J. (1999). Concurrent and longitudinal relations between children’s playground behavior and social preference, victimization, and bullying. Child Development, 70, 944-954.

Carlson, N. R. (2011). Foundations of behavioral neuroscience (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Carlson, S. M., & White, R. E. (2013). Executive function, pretend play, and imagination. In The Oxford Handbook of the Development of Imagination (pp. 161–174). Oxford University Press.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, April 5). Childhood obesity facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html

Cillessen, A. H., & Mayeaux, L. (2004). From censure to reinforcement: Developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Development, 75, 147-163.

Cohen-Bendahan, C., van de Beek, C., & Berenbaum, S. A. (2005). Prenatal sex hormone effects on child and adult sex-typed behavior: Methods and findings. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 29(2), 353-384.

Deunk, M., Berenst, J., & De Glopper, K. (2008). The development of early sociodramatic play. Discourse Studies, 10(5), 615–633.

Dyer, S., & Moneta, G. B. (2006). Frequency of parallel, associative, and cooperative play in British children of different socio-economic status. Social Behavior and Personality, 34(5), 587-592.

Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. NY: Norton & Company.

Fraser-Thomas, J. L., Côté, J., & Deakin, J. (2005). Youth sport programs: An avenue to foster positive youth development. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 10, 19-40.

Gioia, K. A., & Tobin, R. M. (2010). Role of sociodramatic play in promoting self-regulation. In Play therapy for preschool children (pp. 181–198). American Psychological Association.

Harvard School of Public Health. (n.d.) Child Obesity. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/obesity-prevention-source/obesity-trends/global-obesity-trends-in-children/.

Johnson, M. (2005). Developmental neuroscience, psychophysiology, and genetics. In M. Bornstein & M. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental science: An advanced textbook (5th ed., pp. 187-222). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum

Liang, J., Matheson, B. E., Kaye, W. H., & Boutelle, K. N. (2014). Neurocognitive correlates of obesity and obesity-related behaviors in children and adolescents. International Journal of Obesity (2005) , 38(4), 494–506. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.142

Lillard, A. S., Lerner, M. D., Hopkins, E. J., Dore, R. A., Smith, E. D., & Palmquist, C. M. (2013). The impact of pretend play on children’s development: A review of the evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 1–34.

Lu, S. (2016). Obesity and the growing brain. Monitor on Psychology, 47(6), 40-43.

Markant, J. C., & Thomas, K. M. (2013). Postnatal brain development. In P. D. Zelazo (Ed.), Oxford handbook of developmental psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

McGuine, T. A. (2016). The association of sport specialization and the history of lower extremity injury in high school athletes. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 48, 866. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000487597.82416.4d

Parten, M. B. (1932). Social participation among preschool children. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 27, 243-269.

Reid, S. (2017). 4 questions for Mitch Prinstein. Monitor on Psychology, 48(8), 31-32.

Rolls, E. T. (2000). Memory systems in the brain. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 599–630. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.599

Ross, H. S., & Lollis, S. P. (1989). A social relations analysis of toddler peer relations. Child Development, 60, 1082-1091.

Sabo, D., & Veliz, P. (2008). Go out and play: Youth sports in America. East Meadow, NY: Women’s Sports Foundation .

Sobel, D. M., & Lillard, A. S. (2001). The impact of fantasy and action on young children’s understanding of pretence. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 19(1), 85–98.

Sport Policy and Research Collaborative (SPARC, 2013). What is the status of youth coach training in the U.S.? University of Florida. Retrieved from https://assets.aspeninstitute.org/content/uploads/files/content/upload/Project%20Play%20Research%20Brief%20Coaching%20Education%20–%20FINAL.pdf

Sport Policy and Research Collaborative (SPARC, 2016). State of play 2016: Trends and developments. The Aspen Institute. Retrieved from https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/state-play-2016-trends-developments/

Sports and Fitness Industry Association (SFIA). (2018, June 15). Soccer participation in the United States. Medium. https://sfia.medium.com/soccer-participation-in-the-united-states-92f8393f6469

Spreen, O., Rissser, A., & Edgell, D. (1995). Developmental neuropsychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

The Aspen Institute Project Play. (n.d.). Youth Sports Facts: Participation rates. https://www.aspenprojectplay.org/youth-sports/facts/participation-rates

The Aspen Institute Project Play. (2022). State of Play, Oakland. https://projectplay.org/communities/oakland

United States Youth Soccer. (2012). US youth soccer at a glance. Retrieved from http://www.usyouthsoccer.org/media_kit/ataglance/

van der Molen, M., & Molenaar, P. (1994). Cognitive psychophysiology: A window to cognitive development and brain maturation. In G. Dawson & K. Fischer (Eds.), Human behavior and the developing brain. New York: Guilford.