Section 9: Emerging and Early Adulthood

9.4 Psychosocial Development in Early Adulthood

What is psychosocial development like in emerging adulthood?

From a lifespan developmental perspective, growth and development do not stop in childhood or adolescence; they continue throughout adulthood. In this section, we will build on Erikson’s psychosocial stages and then be introduced to theories about transitions that occur during adulthood. According to Levinson, we alternate between periods of change and periods of stability. More recently, Arnett notes that transitions to adulthood happen at later ages than in the past, and he proposes that there is a new stage between adolescence and early adulthood called “emerging adulthood.” Let’s see what you think.

Learning Objectives

- Describe Erikson’s stage of intimacy vs. isolation

- Describe the relationship between infant and adult temperament

- Explain the five-factor model of personality

- Describe adult attachment styles

- Summarize attachment theory in adulthood

Theories of Early Adult Psychosocial Development

Erikson’s Theory

Erikson’s (1950, 1968) sixth stage of psychosocial development focuses on establishing intimate relationships or risking social isolation. Intimate relationships are more difficult if one is still struggling with identity. Achieving a sense of identity is a life-long process, as there are periods of identity crisis and stability. Once a sense of identity is established, young adults’ focus often turns to intimate relationships. The word “intimacy” is often used to describe romantic or sexual relationships, but it also refers to the closeness, caring, and personal disclosure that can be found in many other types of relationships as well– and, of course, it is possible to have sexual relationships that do not include psychological intimacy or closeness. The need for intimacy can be met in many ways, including with friendships, familial relationships, and romantic relationships.

| Table 1. Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages of Development | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | Age (years) | Developmental Task | Description |

| 1 | 0–1 | Trust vs. mistrust | Trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met |

| 2 | 1–3 | Autonomy vs. shame/doubt | Develop a sense of independence in many tasks |

| 3 | 3–6 | Initiative vs. guilt | Take initiative on some activities—may develop guilt when unsuccessful or boundaries overstepped |

| 4 | 7–11 | Industry vs. inferiority | Develop self-confidence in abilities when competent or a sense of inferiority when not |

| 5 | 12–18 | Identity vs. Confusion | Experiment with and develop identity and roles |

| 6 | 19–29 | Intimacy vs. isolation | Establish intimacy and relationships with others |

| 7 | 30–64 | Generativity vs. stagnation | Contribute to society and be part of a family |

| 8 | 65– | Integrity vs. despair | Assess and make sense of life and the meaning of contributions |

Intimacy vs. Isolation

Erikson (1950) believed that the main task of early adulthood is to establish intimate relationships and not feel isolated from others. Intimacy does not necessarily involve romance; it involves caring about another and sharing one’s self without losing one’s self. This developmental crisis of “intimacy versus isolation” is affected by how the adolescent crisis of “identity versus role confusion” was resolved (in addition to how the earlier developmental crises in infancy and childhood were resolved). The young adult might be afraid to get too close to someone else and lose her or his sense of self, or the young adult might define her or himself in terms of another person.

While identity is a life-long process, having some sense of identity is essential for intimate relationships. However, consider what that would mean for previous generations of women who may have defined themselves through their husbands and marriages or for Eastern cultures today that value interdependence rather than independence.

People in early adulthood (the 20s through 40) are concerned with intimacy vs. isolation. After we have developed a sense of self in adolescence, we are ready to share our life with others. However, if other stages have not been successfully resolved, young adults may have trouble developing and maintaining successful relationships with others. Erikson said that we must have a strong sense of self before we can develop successful intimate relationships. Adults who do not develop a positive self-concept in adolescence may experience feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation.

Friendships as a source of intimacy

In our twenties, intimacy needs may be met in friendships rather than with partners. This is especially true in the United States today as many young adults postpone making long-term commitments to partners either in marriage or in cohabitation. Friendships provide one common way to achieve a sense of intimacy. In early adulthood, healthy friendships continue to be important for development, providing not only a source of support in tough times but also improved self-esteem and general well-being (Berk, 2014; Collins & Madsen, 2006; Deci et al., 2006). As is the case in adolescence, friendships rich in intimacy, mutuality, and closeness are especially important for development (Blieszner & Roberto, 2012).

The kinds of friendships shared by women tend to differ from those shared by men (Berk, 2014; Sherman, de Vries, & Lansford, 2000).

- Friendships between men are more likely to involve sharing information, providing solutions, or focusing on activities rather than discussing problems or emotions. Men tend to discuss opinions or factual information or spend time together in an activity of mutual interest.

- Friendships between women are more likely to focus on sharing weaknesses, emotions, or problems. Women talk about difficulties they are having in other relationships and express their sadness, frustrations, and joys.

These differences in approaches could lead to problems when men and women come together. She may want to vent about a problem she is having; he may want to provide a solution and move on to some activity. But when he offers a solution, she thinks he does not care! Effective communication is the key to good relationships.

Many argue that other-sex friendships become more difficult for heterosexual men and women because of the unspoken question about whether the friendships will lead to a romantic involvement. Although common during adolescence and early adulthood, these friendships may be considered threatening once a person is in a long-term relationship or marriage. Consequently, friendships may diminish once a person has a partner or single friends may be replaced with couple friends.

Workplace friendships. Friendships often take root in the workplace since people spend as much, or more, time at work as they do with their family and friends (Kaufman & Hotchkiss, 2003). Often, it is through these relationships that people receive mentoring and obtain social support and resources, but they can also experience conflicts and the potential for misinterpretation when sexual attraction is an issue. Indeed, Elsesser and Peplau (2006) found that many workers reported that friendships grew out of collaborative work projects, and these friendships made their days more pleasant. In addition to those benefits, Riordan and Griffeth (1995) found that people who work in an environment where friendships can develop and be maintained are more likely to report higher levels of job satisfaction, job involvement, and organizational commitment, and they are more likely to remain in that job. Similarly, a Gallup poll revealed that employees who had “close friends” at work were almost 50% more satisfied with their jobs than those who did not (Armour, 2007).

Internet friendships. What influence does the Internet have on friendships? It is not surprising that people use the Internet with the goal of meeting and making new friends (Fehr, 2008; McKenna, 2008). Researchers have wondered whether virtual relationships (compared to ones conducted face-to-face) reduce the authenticity of relationships or whether the Internet actually allows people to develop deep, meaningful connections. Interestingly, research has demonstrated that virtual relationships are often as intimate as in-person relationships; in fact, Bargh and colleagues found that online relationships are sometimes more intimate (Bargh et al., 2002). This can be especially true for those individuals who are socially anxious and lonely—such individuals are more likely to turn to the Internet to find new and meaningful relationships (McKenna et al. 2002). McKenna et al. (2002) suggest that for people who have a hard time meeting and maintaining relationships due to shyness, anxiety, or lack of face-to-face social skills, the Internet provides a safe, non-threatening place to develop and maintain relationships. Similarly, Benford (2008) found that for high-functioning autistic individuals, the Internet facilitates communication and relationship development with others, which would be more difficult in face-to-face contexts, leading to the conclusion that Internet communication can be empowering for those who feel dissatisfied when communicating face to face.

Gaining Adult Status

Many of the developmental tasks of early adulthood involve becoming part of the adult world and gaining independence. Young adults sometimes complain that they are not treated with respect, especially if they are put in positions of authority over older workers. Consequently, young adults may emphasize their age to gain credibility from those who are even slightly younger. “You’re only 23? I’m 27!” a young adult might exclaim. [Note: This kind of statement is much less likely to come from someone in their 40s!]

The focus of early adulthood is often on the future. Many aspects of life are on hold while people seek additional education, go to work, and prepare for a brighter future. There may be a belief that the hurried life now lived will improve ‘as soon as I finish school’ or ‘as soon as I get promoted’ or ‘as soon as the children get a little older.’ As a result, time may seem to pass rather quickly. The day consists of meeting many demands that these tasks bring. The incentive for working so hard is that it will all result in a better future.

Adulthood, then, is a period of building and rebuilding one’s life. Many of the decisions that are made in early adulthood are made before a person has had enough experience to really understand the consequences of such decisions. And, perhaps, many of these initial decisions are made with one goal in mind – to be seen as an adult. As a result, early decisions may be driven more by the expectations of others. For example, imagine someone who chose a career path based on other’s advice but now finds that the job is not what was expected.

Personality

Beyond providing insights into the general outline of adult personality development, Roberts et al. (2006) found that young adulthood (the period between the ages of 18 and the late 20s) was the most active time in the lifespan for observing average changes, although average differences in personality attributes were observed across the lifespan. Such a result might be surprising in light of the intuition that adolescence is a time of personality change and maturation. However, young adulthood is typically a time in the lifespan that includes a number of life changes in terms of finishing school, starting a career, committing to romantic partnerships, and parenthood (Donnellan et al., 2007; Rindfuss, 1991). Finding that young adulthood is an active time for personality development provides circumstantial evidence that adult roles might generate pressures for certain patterns of personality development. Indeed, this is one potential explanation for the maturity principle of personality development.

It should be emphasized again that average trends are summaries that do not necessarily apply to all individuals. Some people do not conform to the maturity principle. The possibility of exceptions to general trends is the reason it is necessary to study individual patterns of personality development. The methods for this kind of research are becoming increasingly popular (Vaidya et al., 2008), and existing studies suggest that personality changes differ across people (Roberts & Mroczek, 2008). These new research methods work best when researchers collect more than two waves of longitudinal data covering longer spans of time. This kind of research design is still somewhat uncommon in psychological studies, but it will likely characterize the future of research on personality stability.

Temperament in Early Adulthood

Remember, temperament is defined as the innate characteristics of the infant, including mood, activity level, and emotional reactivity, noticeable soon after birth. Does one’s temperament remain stable through the lifespan? Do shy and inhibited babies grow up to be shy adults, while the sociable child continues to be the life of the party? Like most developmental research, the answer is more complicated than a simple yes or no.

Chess and Thomas (1984), who identified children as easy, difficult, slow-to-warm-up, or blended, found that children identified as easy grew up to become well-adjusted adults, while those who exhibited a difficult temperament were not as well-adjusted as adults. Kagan (2003) has studied the temperamental category of inhibition to the unfamiliar in children. Infants exposed to unfamiliarity reacted strongly to the stimuli and cried loudly, pumped their limbs, and had an increased heart rate. Research has indicated that these highly reactive children show temperamental stability into early childhood, and Bohlin and Hagekull (Bohlin & Hagekull, 2009) found that shyness in infancy was linked to social anxiety in adulthood.

An important aspect of this research on inhibition was looking at the response of the amygdala, which is important for fear and anxiety, especially when confronted with possible threatening events in the environment. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRIs) young adults identified as strongly inhibited toddlers showed heightened activation of the amygdala when compared to those identified as uninhibited toddlers (Davidson & Begley, 2013).

The research does seem to indicate that temperamental stability holds for many individuals throughout their lifespan, yet we know that one’s environment can also have a significant impact. Recall from our discussion on epigenesis or how environmental factors are thought to change gene expression by switching genes on and off. Many cultural and environmental factors can affect one’s temperament, including supportive versus abusive child-rearing, socioeconomic status, stable homes, illnesses, teratogens, etc. Additionally, individuals often choose environments that support their temperament, which in turn further strengthens them (Cain, 2012).

In summary, because temperament is genetically driven, genes appear to be the major reason why temperament remains stable into adulthood. In contrast, the environment appears mainly responsible for any change in temperament (Clark & Watson, 1999).

Everybody has their own unique personality; that is, their characteristic manner of thinking, feeling, behaving, and relating to others (John et al., 2008). Personality traits refer to these characteristic, routine ways of thinking, feeling, and relating to others. Personality integrates one’s temperament with cultural and environmental influences. Consequently, there are signs or indicators of these traits in childhood, but they become particularly evident when the person is an adult. Personality traits are integral to each person’s sense of self, as they involve what people value, how they think and feel about things, what they like to do, and, basically, what they are like almost every day throughout much of their lives.

Trait Theory: Five-Factor Model (Big 5)

There are hundreds of different personality traits, and all of these traits can be organized into the broad dimensions referred to as the Five-Factor Model (John et al., 2008). These five broad domains include Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (Think OCEAN to remember). This applies to traits that you may use to describe yourself. Table 2 provides illustrative traits for low and high scores on the five domains of this model of personality.

|

Dimension |

Description |

Examples of behaviors predicted by the trait |

|

Openness to experience |

A general appreciation for art, emotion, adventure, unusual ideas, imagination, curiosity, and variety of experience |

Individuals who are highly open to experience tend to have distinctive and unconventional decorations in their homes. They are also likely to have books on a wide variety of topics, a diverse music collection, and works of art on display. |

|

Conscientiousness |

A tendency to show self-discipline, act dutifully, and aim for achievement |

Individuals who are conscientious have a preference for planned rather than spontaneous behavior. |

|

Extraversion |

The tendency to experience positive emotions and to seek out stimulation and the company of others |

Extroverts enjoy being with people. In groups, they like to talk, assert themselves, and draw attention to themselves. |

|

Agreeableness |

A tendency to be compassionate and cooperative rather than suspicious and antagonistic toward others reflects individual differences in general concern for social harmony |

Agreeable individuals value getting along with others. They are generally considerate, friendly, generous, helpful, and willing to compromise their interests with those of others. |

|

Neuroticism |

The tendency to experience negative emotions, such as anger, anxiety, or depression, sometimes called “emotional instability” |

Those who score high in neuroticism are more likely to interpret ordinary situations as threatening and minor frustrations as hopelessly difficult. They may have trouble thinking clearly, making decisions, and coping effectively with stress. |

Personality can change throughout adulthood. Longitudinal studies reveal average changes during adulthood in the expression of some traits (e.g., neuroticism and openness decrease with age and conscientiousness increases) and individual differences in these patterns due to idiosyncratic life events (e.g., divorce, illness). Longitudinal research also suggests that adult personality traits, such as conscientiousness, predict important life outcomes, including job success, health, and longevity (Friedman et al., 1993; Roberts et al., 2007).

The Harvard Health Letter (2012) identifies research correlations between conscientiousness and lower blood pressure, lower rates of diabetes and stroke, fewer joint problems, being less likely to engage in harmful behaviors, being more likely to stick to healthy behaviors, and more likely to avoid stressful situations. Conscientiousness also appears to be related to career choices, friendships, and marriage stability. Lastly, a person possessing both self-control and organizational skills, both related to conscientiousness, may withstand the effects of aging better and have stronger cognitive skills than one who does not possess these qualities.

Attachment

Attachment Theory Review

The need for intimacy, or close relationships with others, is universal and persistent across the lifespan. What our adult intimate relationships look like actually stems from infancy and our relationship with our primary caregiver (historically our mother)—a process of development described by attachment theory, which you learned about in the module on infancy. Recall that according to attachment theory, different styles of caregiving result in different relationship “attachments.”

For example, responsive mothers—mothers who soothe their crying infants—produce infants who have secure attachments (Ainsworth, 1973; Bowlby, 1969). About 60% of all children are securely attached.

- As adults, secure individuals rely on their working models—concepts of how relationships operate—that were created in infancy as a result of their interactions with their primary caregiver (mother) to foster happy and healthy adult intimate relationships. Securely attached adults feel comfortable being depended on and depending on others.

As you might imagine, inconsistent or dismissive parents also impact the attachment style of their infants (Ainsworth, 1973), but in a different direction. In early studies on attachment style, infants were observed interacting with their caregivers, followed by being separated from them, and then finally reunited. About 20% of the observed children were “resistant,” meaning they were anxious even before, and especially during, the separation, and 20% were “avoidant,” meaning they actively avoided their caregiver after separation (i.e., ignoring the mother when they were reunited). These early attachment patterns can affect the way people relate to one another in adulthood.

- Anxious-resistant adults worry that others don’t love them, and they often become frustrated or angry when their needs go unmet. Anxious-avoidant adults will appear not to care much about their intimate relationships and are uncomfortable being depended on or depending on others themselves.

The good news is that our attachment can be changed. It isn’t easy, but it is possible for anyone to “recover” a secure attachment. The process often requires the help of a supportive and dependable other, and for the insecure person to achieve coherence—the realization that his or her upbringing is not a permanent reflection of character or a reflection of the world at large, nor does it bar him or her from being worthy of love or others of being trustworthy (Treboux et al., 2004).

To learn more, watch this video from The School of Life, “What is Your Attachment Style?”

Attachment in Young Adulthood

Hazan and Shaver (1987) described the attachment styles of adults using the same three general categories proposed by Ainsworth’s research on young children: secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent. Hazan and Shaver developed three brief paragraphs describing the three adult attachment styles. Adults were then asked to think about romantic relationships they were in and select the paragraph that best described the way they felt, thought, and behaved in these relationships (See Table 3.)

|

Secure |

I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t often worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me. |

|

Avoidant |

I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, love partners want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being. |

|

Anxious/Ambivalent |

I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t stay with me. I want to merge completely with another person, and this sometimes scares people away. |

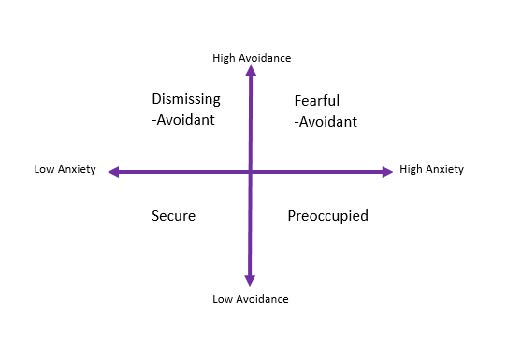

Bartholomew (1990) challenged the categorical view of attachment in adults and suggested that adult attachment was best described as varying along two dimensions: attachment-related anxiety and attachment-related avoidance.

- Attachment-related anxiety refers to the extent to which an adult worries about whether their partner really loves them. Those who score high on this dimension fear that their partner will reject or abandon them (Fraley et al., 2015).

- Attachment-related avoidance refers to whether an adult can open up to others and whether they trust and feel they can depend on others. Those who score high on attachment-related avoidance are uncomfortable with opening up and may fear that such dependency may limit their sense of autonomy (Fraley et al., 2015). According to Bartholomew (1990), this would yield four possible attachment styles in adults: secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful-avoidant (see Figure 5)

Securely attached adults score lower on both dimensions. They are comfortable trusting their partners and do not worry excessively about their partner’s love for them. Adults with a dismissing style score low on attachment-related anxiety but higher on attachment-related avoidance. Such adults dismiss the importance of relationships. They trust themselves but do not trust others, thus not sharing their dreams, goals, and fears with others. They do not depend on other people and feel uncomfortable when they have to do so.

Those with a preoccupied attachment are low in attachment-related avoidance but high in attachment-related anxiety. Such adults are often prone to jealousy and worry that their partner does not love them as much as they need to be loved. Adults whose attachment style is fearful-avoidant score high on both attachment-related avoidance and attachment-related anxiety. These adults want close relationships but do not feel comfortable getting emotionally close to others. They have trust issues with others and often do not trust their own social skills in maintaining relationships.

Other research on attachment in adulthood has found that:

- Adults with insecure attachments report lower satisfaction in their relationships (Butzer & Campbell, 2008; Holland et al., 2012).

- Those high in attachment-related anxiety tend to report more daily conflict in their relationships. (Campbell et al., 2005).

- Those with avoidant attachment exhibit less support for their partners (Simpson et al., 2002).

- Young adults tend to show greater attachment-related anxiety than middle-aged or older adults (Chopik et al., 2013).

- Some studies report that young adults tend to show more attachment-related avoidance (Schindler et al., 2010), while other studies find that middle-aged adults tend to show higher avoidance than younger or older adults (Chopik et al., 2013).

- Young adults with more secure and positive relationships with their parents tend to make the transition to adulthood more easily than those with more insecure attachments (Fraley, 2013).

- Young adults with secure attachments and authoritative parents were less likely to be depressed than those with authoritarian or permissive parents or who experienced an avoidant or ambivalent attachment (Ebrahimi, Amiri, Mohamadlou, & Rezapur, 2017).

Do people with certain attachment styles attract those with similar styles?

When people are asked what kinds of psychological or behavioral qualities they are seeking in a romantic partner, a large majority of people indicate that they are seeking someone who is kind, caring, trustworthy, and understanding; those are the kinds of attributes that characterize a “secure” caregiver. (Chappell & Davis, 1998). However, we know that people do not always end up with others who meet their ideals. Are secure people more likely to end up with secure partners, and, vice versa, are insecure people more likely to end up with insecure partners? The majority of the research that has been conducted to date suggests that the answer is “yes.” Frazier et al. (1996) studied the attachment patterns of more than 83 heterosexual couples and found that if the man was relatively secure, the woman was also likely to be secure.

One important question is whether these findings exist because (a) secure people are more likely to be attracted to other secure people, (b) secure people are likely to create security in their partners over time, or (c) some combination of these possibilities. Existing empirical research strongly supports the first alternative. For example, when people have the opportunity to interact with individuals who vary in security in a speed-dating context, they express a greater interest in those who are higher in security than those who are more insecure (McClure et al., 2010). However, there is also some evidence that people’s attachment styles mutually shape one another in close relationships.

Childhood experiences shape adult attachment

The majority of research on this issue relies on adults’ reports of what they recall about their childhood experiences. This kind of work suggests that secure adults are more likely to describe their early childhood experiences with their parents as being supportive, loving, and kind (Hazan Shaver, 1987). A number of longitudinal studies are emerging that demonstrate prospective associations between early attachment experiences and adult attachment styles and/or interpersonal functioning in adulthood.

It is easy to come away from such findings with the mistaken assumption that early experiences “determine” later outcomes. To be clear, Attachment theorists assume that the relationship between early experiences and subsequent outcomes is probabilistic, not deterministic. Having supportive and responsive experiences with caregivers early in life is assumed to set the stage for positive social development. However, that does not mean that attachment patterns cannot change over time. For instance, even if an individual has far from optimal experiences in early life, attachment theory suggests that it is possible for that individual to develop well-functioning adult relationships through a number of corrective experiences, including relationships with siblings, other family members, teachers, and close friends. Security is best viewed as a culmination of a person’s attachment history rather than a reflection of only the person’s early experiences. Those early experiences are considered important, not because they determine a person’s fate, but because they provide the foundation for subsequent experiences.

Additional Resources

Websites

- Society for the Study of Emerging Adulthood

- SSEA is a multidisciplinary, international organization with a focus on theory and research related to emerging adulthood, which includes the age range of approximately 18 through 29 years. The website includes information on topics, events, and publications pertaining to emerging adults from diverse backgrounds, cultures, and countries.

- On the Cusp of Adulthood: What we know about Gen Z so far

- Aside from the unique set of circumstances in which Gen Z is approaching adulthood, what do we know about this new generation? Pew Research Center

- Article: The People Who Prioritize a Friendship Over Romance – The Atlantic

- What if friendship, and not marriage, was at the center of life?

Videos

- Why does it take so long to grow up today? | Jeffrey Jensen Arnett | TEDxPSU

- It takes so long to “grow up” today—finish education, find a stable job, get married—that it makes sense to think of it as a new life stage, emerging adulthood, in between adolescence and young adulthood. But why? Arnett coined the phrase emerging adulthood, the phase of life between adolescence and full-fledged adulthood.

- Why 30 is Not the New 20 TED talk

- Clinical psychologist Meg Jay has a bold message for twentysomethings: Contrary to popular belief, your 20s are not a throwaway decade. In this provocative talk, Jay says that just because marriage, work, and kids are happening later in life, doesn’t mean you can’t start planning now.

- The Love Competition

- The World’s First Annual Love Competition. Because “Love is a feeling you have for someone you have feelings about.”

Attributions

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Love, Friendship, and Social Support by Debi Brannan and Cynthia D. Mohr is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Additional written material by Ellen Skinner & Heather Brule, Portland State University, is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

References

Ainsworth, M. S. (1973). Infant–mother attachment. American Psychologist, 34(10), 932–937. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.932

Armour, S. (2007, August 2). Friendships and work: A good or bad partnership? USA Today. Retrieved from http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/workplace/2007-08-01-work-friends_N.htm

Arnett, J. J. (2003). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2003(100), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.75

Bargh, J. A., McKenna, K. Y. A, & Fitsimons, G. G. (2002). Can you see the real me? Activation and expression of the true self on the Internet. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 33–48.

Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 147-178. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3524.61.2.226.

Benford, P. (2008). The use of Internet-based communication by people with autism (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nottingham).

Berk, Laura E. (2014). Exploring lifespan development (3rd ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Blieszner, R., & Roberto, K. A. (2012). Partners and friends in adulthood. In S. K. Whitbourne & M. J. Sliwinski (Eds.), Handbooks of developmental psychology. The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of adulthood and aging (p. 381–398). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118392966.ch19

Bohlin, G., & Hagekull, B. (2009). Socio-emotional development: from infancy to young adulthood. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 50(6), 592–601. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00787.x

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Loss. New York: Basic Books.

Butzer, B., & Campbell, L. (2008). Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships, 15, 141-154.

Cain, S. (2012). Quiet. New York: Crown Publishing Group.

Campbell, L., Simpson, J. A., Boldry, J., & Kashy, D. A. (2005). Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: The role of attachment anxiety. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 510-532.

Chappell, K. D., & Davis, K. E. (1998). Attachment, partner choice, and perception of romantic partners: An experimental test of the attachment-security hypothesis. Personal Relationships, 5, 327–342.

Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1984). Origins and evolution of behavior disorders: From infancy to early adult life. Harvard University Press.

Chopik, W. J., Edelstein, R. S., & Fraley, R. C. (2013). From the cradle to the grave: Age differences in attachment from early adulthood to old age. Journal or Personality, 81 (2), 171-183 DOI: 10.1111/j. 1467-6494.2012.00793Cicirelli, V. (2009). Sibling relationships, later life. In D. Carr (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the life course and human development. Boston, MA: Cengage.

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1999). Temperament: A new paradigm for trait psychology. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 399–423). Guilford Press.

Collins, W. A., & Madsen, S. D. (2006). Personal Relationships in Adolescence and Early Adulthood. In A. L. Vangelisti & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (p. 191–209). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606632.012

Deci, E. L., La Guardia, J. G., Moller, A. C., Scheiner, M. J., & Ryan, R. M. (2006). On the benefits of giving as well as receiving autonomy support: Mutuality in close friendships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(3), 313-327.

Donnellan, M. B., Trzesniewski, K. H., Robins, R. W., Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2007). Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychological Science, 16(4), 328-335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01695.x

Ebrahimi, L., Amiri, M., Mohamadlou, M., & Rezapur, R. (2017). Attachment styles, parenting styles, and depression. International Journal of Mental Health, 15, 1064-1068.

Elsesser, L., & Peplau, L. A. (2006). The glass partition: Obstacles to cross-sex friendships at work. Human Relations, 59(8), 1077–1100.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Fehr, B. (2008). Friendship formation. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel, & J. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of Relationship Initiation (pp. 29–54). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Fraley, R. C., Hudson, N. W., Heffernan, M. E., & Segal, N. (2015). Are adult attachment styles categorical or dimensional? A taxometric analysis of general and relationship-specific attachment orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(2), 354–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000027

Frazier, P. A, Byer, A. L., Fischer, A. R., Wright, D. M., & DeBord, K. A. (1996). Adult attachment style and partner choice: Correlational and experimental findings. Personal Relationships, 3, 117–136.

Friedman, H. S., Tucker, J. S., Tomlinson-Keasey, C., Schwartz, J. E., Wingard, D. L., & Criqui, M. H. (1993). Does childhood personality predict longevity? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(1), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.1.176

Harvard Health Letter. (2012). Raising your conscientiousness. http://www.helath.harvard.edu

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 (3), 511-524.

Holland, A. S., Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2012). Attachment styles in dating couples: Predicting relationship functioning over time. Personal Relationships, 19, 234-246. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01350.x

John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 114-158). Guilford Press.

Masci, D., Sciupac, E. P., & Lipka, M. (2019). Same-Sex Marriage Around the World. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/fact-sheet/gay-marriage-around-the-world/

McClure, A. C., Tanski, S. E., Kingsbury, J., Gerrard, M., & Sargent, J. D. (2010). Characteristics associated with low self-esteem among U.S. adolescents. Pediatrics, 125(3), 238-244. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0312

McKenna, K. A. (2008) MySpace or your place: Relationship initiation and development in the wired and wireless world. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel, & J. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of relationship initiation (pp. 235–247). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

McKenna, K. Y. A., Green, A. S., & Gleason, M. E. J. (2002). Relationship formation on the Internet: What’s the big attraction? Journal of Social Issues, 58, 9–31.

Rindfuss, R. R. (1991). The young adult years: Diversity, structural change, and fertility. Demography, 28(4), 493-512. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061419

Riordan, C. M., & Griffeth, R. W. (1995). The opportunity for friendship in the workplace: An underexplored construct. Journal of Business and Psychology, 10, 141–154.

Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N. R., Shiner, R., Caspi, A., & Goldberg, L. R. (2007). The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 2(4), 313–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x

Sherman, A. M., De Vries, B., & Lansford, J. E. (2000). Friendship in childhood and adulthood: Lessons across the life span. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 51(1), 31-51.

Sorokowski, P., Randall, A. K., Groyecka, A., Frackowiak, T., Cantarero, K., Hilpert, P., Ahmadi, K., Alghraibeh, A. M., Aryeetey, R., Bertoni, A., Bettache, K., Blazejewska, M., Bodenmann, G., Bortolini, T. S., Bosc, C., Butovskaya, M., Castro, F. N., Cetinkaya, H., Cunha, D., David, D., David, O. A., Espinosa, A. C. D., Donato, S., Dronova, D., Dural, S., Fisher, M., Akkaya, A. H., Hamamura, T., Hansen, K., Hattori, W. T., Hromatko, I., Gulbetekin, E., Iafrate, R., James, B., Jiang, F., Kimamo, C. O., Koç, F., Krasnodebska, A., Laar, A., Lopes, F. A., Martinez, R., Mesko, N., Molodovskaya, N., Qezeli, K. M., Motahari, Z., Natividade, J. C., Ntayi, J., Ojedokun, O., Mohd, M. S., Onyishi, I. E., Özener, B., Paluszak, A., Portugal, A., Realo, A., Relvas, A. P., Rizwan, M., Sabiniewicz, A. L., Salkicevic, S., Sarmány-Schuller, I., Stamkou, E., Stoyanova, S., Šukolová, D., Sutresna, N., Tadinac, M., Teras, A., Edna, E. L., Tripathi, R., Tripathi, N., Tripathi, M., Yamamoto, M. E., Yoo, G., & Sorokowska, A. (2017). Marital satisfaction, sex, age, marriage duration, religion, number of children, economic status, education, and collectivistic values: Data from 33 countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1199. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01199

Treboux, D., Crowell, J. A., & Waters, E. (2004). When “new” meets “old”: configurations of adult attachment representations and their implications for marital functioning. Developmental Psychology, 40(2), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.295