Section 9: Emerging and Early Adulthood

9.5 Relationships in Early Adulthood

From Erikson, we have learned that the psychosocial developmental task of early adulthood is “intimacy versus isolation,” and if resolved relatively positively, it can lead to the virtue of “love.” In this section, we will look more closely at relationships in early adulthood, particularly in terms of love, dating, cohabitation, and marriage.

Learning Objectives

- Explain adult gender identity and gender roles

- Describe some factors related to attraction in relationships

- Describe trends and norms in dating, cohabitation, and marriage across the world

- Describe new parenthood.

Relationships with Parents, Caregivers, and Siblings

In early adulthood, the parent-child relationship transitions by necessity toward a relationship between two adults. This involves a reappraisal of the relationship by both parents and young adults. One of the biggest challenges for parents, especially during emerging adulthood, is coming to terms with the adult status of their children. Aquilino (2006) suggests that parents who are reluctant or unable to do so may hinder young adults’ identity development. This problem becomes more pronounced when young adults still reside with their parents and are financially dependent on them. Arnett (2004) reported that leaving home often helped promote psychological growth and independence in early adulthood.

Sibling relationships are one of the longest-lasting bonds in people’s lives. Yet, there is little research on the nature of sibling relationships in adulthood (Aquilino, 2006). What is known is that the nature of these relationships changes as adults have a choice as to whether they will create or maintain a close bond and continue to be a part of the life of a sibling. Siblings must make the same reappraisal of each other as adults, as parents have to with their adult children. Research has shown a decline in the frequency of interactions between siblings during early adulthood, as presumably peers, romantic relationships, and children become more central to the lives of young adults. Aquilino (2006) suggests that the task in early adulthood may be to maintain enough of a bond so that there will be a foundation for this relationship in later life. Those who are successful can often move away from the “older-younger” sibling conflicts of childhood toward a more egalitarian relationship between two adults. Siblings that were close to each other in childhood are typically close in adulthood (Dunn, 1984, 2007), and in fact, it is unusual for siblings to develop closeness for the first time in adulthood. Overall, the majority of adult sibling relationships are close (Cicirelli, 2009).

Attraction and Love

Attraction

Why do some people hit it off immediately? Or decide that the friend of a friend was not likable? Using scientific methods, psychologists have investigated factors influencing attraction and have identified a number of variables, such as similarity, proximity (physical or functional), familiarity, and reciprocity, that influence with whom we develop relationships.

Proximity. Often, we “stumble upon” friends or romantic partners; this happens partly due to how close in proximity we are to those people. Specifically, proximity or physical nearness has been found to be a significant factor in the development of relationships. For example, when college students go away to a new school, they will make friends consisting of classmates, roommates, and teammates (i.e., people close in proximity). Proximity allows people the opportunity to get to know one another and discover their similarities—all of which can result in a friendship or intimate relationship. Proximity is not just about geographic distance but rather functional distance or the frequency with which we cross paths with others.

For example, college students are more likely to become closer and develop relationships with people on their dorm-room floors because they see them (i.e., cross paths) more often than they see people on a different floor. How does the notion of proximity apply in terms of online relationships? Deb Levine (2000) argues that in terms of developing online relationships and attraction, functional distance refers to being at the same place at the same time in a virtual world (i.e., a chat room or Internet forum)—crossing virtual paths.

Familiarity. One of the reasons why proximity matters to attraction is that it breeds familiarity; people are more attracted to that which is familiar. Just being around someone or being repeatedly exposed to them increases the likelihood that we will be attracted to them. We also tend to feel safe with familiar people, as it is likely we know what to expect from them. Dr. Robert Zajonc (1968) labeled this phenomenon the mere exposure effect. More specifically, he argued that the more often we are exposed to a stimulus (e.g., sound, person), the more likely we are to view that stimulus positively. Moreland and Beach (1992) demonstrated this by exposing a college class to four women (similar in appearance and age) who attended different numbers of classes, revealing that the more classes a woman attended, the more familiar, similar, and attractive she was considered by the other students.

There is a certain comfort in knowing what to expect from others; consequently, research suggests that we like what is familiar. While this is often on a subconscious level, research has found this to be one of the most basic principles of attraction (Zajonc, 1980). For example, a young man growing up with an overbearing mother may be attracted to other overbearing women not because he likes being dominated but rather because it is what he considers normal (i.e., familiar).

Similarity. When you hear about celebrity couples, do you shake your head thinking, “This won’t last”? It is probably because they seem so different. While many make the argument that opposites attract, research has found that is generally not true; similarity is key. Sure, there are times when couples can appear fairly different, but overall, we like others who are like us. Ingram and Morris (2007) examined this phenomenon by inviting business executives to a cocktail mixer, 95% of whom reported that they wanted to meet new people. Using electronic name tag tracking, researchers revealed that the executives did not mingle or meet new people; instead, they only spoke with those they already knew well (i.e., people who were similar).

Research has found that couples tend to be very similar in marriage, particularly in age, social class, race, education, physical attractiveness, values, and attitudes (McCann Hamilton, 2007; Taylor et al., 2011). This phenomenon is known as the matching hypothesis (Feingold, 1988; Mckillip & Redel, 1983). We like others who validate our points of view and who are similar in thoughts, desires, and attitudes.

Reciprocity. Another key component in attraction is reciprocity; this principle is based on the notion that we are more likely to like someone if they feel the same way toward us. In other words, it is hard to be friends with someone who is not friendly in return. Another way to think of it is that relationships are built on give and take; if one side is not reciprocating, then the relationship is doomed. Basically, we feel obliged to give what we get and to maintain equity in relationships. Researchers have found that this is true across cultures (Gouldner, 1960).

Self-Disclosure. Liking is also enhanced by self-disclosure, the tendency to communicate frequently, without fear of reprisal, and in an accepting and empathetic manner. Friends are friends because we can talk to them openly about our needs and goals and because they listen and respond to our needs (Reis & Aron, 2008). However, self-disclosure must be balanced. If we open up about our concerns that are important to us, we expect our partner to do the same in return. If the self-disclosure is not reciprocal, the relationship may not last.

Love

Is all love the same? Are there different types of love? Examining these questions more closely, Robert Sternberg’s (2004; 2007) work has focused on the notion that all types of love are comprised of three distinct areas: intimacy, passion, and commitment.

Intimacy involves the ability to share feelings, psychological closeness, and personal thoughts with the other.

The passion component of love is comprised of physiological and emotional arousal; these can include physical attraction, emotional responses that promote physiological changes, and sexual arousal. Passion refers to the intense physical attraction partners feel toward one another.

Lastly, commitment refers to the cognitive process and decision to commit to loving another person and the willingness to work to keep that love over the course of your life. It is the conscious decision to stay together

The elements involved in intimacy (caring, closeness, and emotional support) are generally found in all types of close relationships—for example, a mother’s love for a child or the love that friends share. Interestingly, this is not true for passion. Passion is unique to romantic love, differentiating friends from lovers.

Although many would agree that all three components are important to a relationship, many love relationships do not consist of all three. Let’s look at other possibilities.

Liking. In this kind of relationship, intimacy or knowledge of the other and a sense of closeness is present. Passion and commitment, however, are not. Partners feel free to be themselves and disclose personal information. They may feel that the other person knows them well and can be honest with them and let them know if they think the person is wrong. These partners are friends. However, being told that your partner “thinks of you as a friend” can be a painful blow if you are attracted to them and seeking a romantic involvement.

Infatuation. Perhaps, this is Sternberg’s version of “love at first sight” or what adolescents would call a “crush.” Infatuation consists of an immediate, intense physical attraction to someone. A person who is infatuated finds it hard to think of anything but the other person. Brief encounters are played over and over in one’s head; it may be difficult to eat, and there may be a rather constant state of arousal. Infatuation is typically short-lived, however, lasting perhaps only a matter of months or as long as a year or so. It tends to be based on physical attraction and an image of what one “thinks” the other is all about.

Fatuous Love. However, some people who have a strong physical attraction push for commitment early in the relationship. Passion and commitment are aspects of fatuous love. There is no intimacy, and the commitment is premature. Partners rarely talk seriously or share their ideas. They focus on their intense physical attraction, yet one or both are also talking about making a lasting commitment. Sometimes, insistence on premature commitment follows from a sense of insecurity and a desire to make sure the partner is locked into the relationship.

Empty Love. This type of love may be found later in a relationship or in a relationship that was formed to meet needs other than intimacy or passion, including financial needs, childrearing assistance, or attaining/maintaining status. Here the partners are committed to staying in the relationship for the children because of a religious conviction or because there are no alternatives. However, they do not share ideas or feelings with each other and have no (or no longer any) physical attraction for one another.

Romantic Love. Intimacy and passion are components of romantic love, but there is no commitment. The partners spend much time with one another and enjoy their closeness but have not made plans to continue. This may be true because they are not in a position to make such commitments or because they are looking for passion and closeness and are afraid it will die out if they commit to one another and start to focus on other kinds of obligations.

Companionate Love. Intimacy and commitment are the hallmarks of companionate love. Partners love and respect one another, and they are committed to staying together. However, their physical attraction may have never been strong or may have just died out over time. Nevertheless, partners are good friends and committed to one another.

Consummate Love. Intimacy, passion, and commitment are present in consummate love, which is often perceived by Western cultures as “the ideal” type of love. The couple shares passion; the spark has not died, and the closeness is there. They feel like best friends as well as lovers, and they are committed to staying together.

Do these types of love mean anything? Is love necessary or helpful for reproduction in humans?

One study tested this hypothesis using Sternberg’s Triangular Love scale as their operational definition of love. The three components of passion, commitment, and intimacy were measured in a traditional hunter-gatherer tribe in Tanzania, and researchers gathered data about which type of relationship was most correlated with successful reproduction.

Try to predict the results of the study.

You were probably able to discern that this study examines the correlation between types of relationships and reproductive success or the number of children a woman has. In psychology, we learn that correlation does NOT equal causation, so just because a person is in a committed relationship, this does not mean they will have children.

So, what does correlation really mean? It means there is a relationship between the variables. Remember that with positive correlation, as one variable increases, so does the other. In a negative correlation, as one variable increases, the other decreases.

Love and the Brain

Taking this theory a step further, anthropologist Helen Fisher explained that she scanned the brains (using fMRI) of people who had just fallen in love and observed that their brain chemistry was “going crazy,” similar to the brain of an addict on a drug high (Cohen, 2007). Specifically, serotonin production increased by as much as 40% in newly-in-love individuals. Further, those newly in love tended to show obsessive-compulsive tendencies. Conversely, when a person experiences a breakup, the brain processes it in a similar way to quitting a heroin habit (Fisher et al., 2009). Thus, those who believe that breakups are physically painful are correct! Another interesting point is that long-term love and sexual desire activate different areas of the brain. More specifically, sexual needs activate the part of the brain that is particularly sensitive to innately pleasurable things such as food, sex, and drugs (i.e., the striatum—a rather simplistic reward system), whereas love requires conditioning—it is more like a habit. When sexual needs are rewarded consistently, then love can develop. In other words, love grows out of positive rewards, expectancies, and habits (Cacioppo et al., 2012).

Dive deeper into Helen Fisher’s research by watching her TED talk “The Brain in Love.”

Trends in Dating, Cohabitation, and Marriage

Single Adulthood

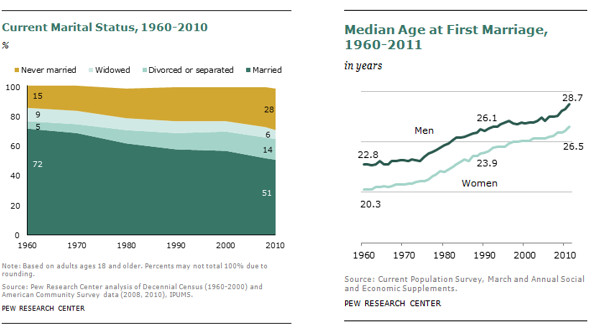

Singlehood. Being single is the most common lifestyle for people in their early 20s, and there has been an increase in the number of adults choosing to remain single. In 1960, only about 1 in 10 adults age 25 or older had never been married, in 2012 that had risen to 1 in 5 (Wang & Parker, 2014). While just over half (53%) of unmarried adults say they would eventually like to get married, 32 percent are not sure, and 13 percent do not want to get married.

It is projected that by the time people who are currently young adults reach their mid-40s and 50s, almost 25% of them may never have married. The U.S. is not the only country to see a rise in the number of single adults. The table below lists some of the reasons young adults give for staying single. In addition, adults are marrying later in life, cohabitating, and raising children outside of marriage in greater numbers than in previous generations. Young adults also have other priorities, such as education and establishing their careers.

Stein’s Typology of Singles

Many of the research findings on singles reveal that they are not all alike. Happiness with one’s status depends on whether the person is single by choice and whether the situation is permanent. Let’s look at Stein’s (1981) four categories of singles for a better understanding of this.

- Voluntary temporary singles: These are younger people who have never been married and divorced people who are postponing marriage and remarriage. They may be more involved in careers, getting an education, or just wanting to have fun without making a commitment to any one person. They are not quite ready for that kind of relationship. These people tend to report being very happy with their single status.

- Voluntary permanent singles: These individuals do not want to marry and do not intend to marry. This might include cohabiting couples who don’t want to marry, priests, nuns, or others who are not considering marriage. Again, this group is typically single by choice and understandably more contented with this decision.

- Involuntary temporary: These are people who are actively seeking mates. They hope to marry or remarry and may be involved in going on blind dates, seeking a partner on the internet, or placing “getting personal” aids in search of a mate. They tend to be more anxious about being single.

- Involuntary permanent: These are older divorced, widowed, or never-married people who wanted to marry but have not found a mate and are coming to accept singlehood as a probable permanent situation. Some are bitter about not having married, while others are more accepting of how their lives have developed.

Dating

In general, traditional dating among teens and those in their early twenties has been replaced with more varied and flexible ways of getting together (and technology with social media, no doubt, plays a key role). The Friday night date with dinner and a movie that those in their 30s may still enjoy gives way to less formal, more spontaneous meetings that may include several couples or a group of friends. Two people may get to know each other and go somewhere alone. How would you describe a “typical” date? Who calls, texts, or FaceTime? Who pays? Who decides where to go? What is the purpose of the date? In general, greater planning is required for people who have additional family and work responsibilities.

Dating and the Internet. The ways people find love have changed with the advent of the Internet. In a poll, 49% of all American adults reported that either they or someone they knew had dated a person they met online (Madden & Lenhart, 2006). As Finkel and colleagues (2007) found, social networking sites and the Internet generally perform three important tasks. Specifically, sites provide individuals with access to a database of other individuals who are interested in meeting someone. Dating sites generally reduce issues of proximity, as individuals do not have to be close in proximity to meet. Also, they provide a medium in which individuals can communicate with others. Finally, some Internet dating websites advertise special matching strategies based on factors such as personality, hobbies, and interests to identify the “perfect match” for people looking for love online. In general, scientific questions about the effectiveness of Internet matching or online dating compared to face-to-face dating remain to be answered.

It is important to note that social networking sites have opened the doors for many to meet people that they might not have ever had the opportunity to meet; unfortunately, it now appears that social networking sites can be forums for unsuspecting people to be duped. In 2010, a documentary, Catfish, focused on the personal experience of a man who met a woman online and carried on an emotional relationship with this person for months. As he later came to discover, though, the person he thought he was talking and writing with did not exist. As Dr. Aaron Ben-Zeév stated, online relationships leave room for deception; thus, people have to be cautious.

Online communication differs from face-to-face interaction in a number of ways. In face-to-face meetings, people have many cues upon which to base their first impressions. A person’s looks, voice, mannerisms, dress, scent, and surroundings all provide information in face-to-face meetings, but in computer-mediated meetings, written messages are the only cues provided. Fantasy is used to conjure up images of voice, physical appearance, mannerisms, and so forth. The anonymity of online involvement may make it easier to become intimate without fear of interdependence. When online, people tend to disclose more intimate details about themselves more quickly. A shy person may open up more without worrying about whether or not the partner is frowning or looking away. And someone who has been abused may feel safer in virtual relationships.

Hooking Up. United States demographic changes have significantly affected romantic relationships among emerging and early adults. As previously described, the age for puberty has declined, while the times for one’s first marriage and first child have increased. This results in a “historically unprecedented time gap where young adults are physiologically able to reproduce but not psychologically or socially ready to settle down and begin a family and child-rearing” (Garcia et al., 2012). Consequently, traditional forms of dating have shifted for some people to include more casual hookups that involve uncommitted sexual encounters (Bogle, 2007; Bogle, 2008).

Concerns regarding hooking-up behavior are evident in the research literature. One significant finding is the high comorbidity of hooking up and substance use. Those engaging in non-monogamous sex are more likely to have used marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol, and the overall risks of sexual activity are drastically increased with the addition of alcohol and drugs (Garcia et al., 2012). Regret has also been expressed, and those who had the most regret after hooking up also had more symptoms of depression (Welsh et al., 2006). Hookups were also found to be associated with lower self-esteem, increased guilt, and fostered feelings of using someone or feeling used.

Hooking up can best be explained by a biological, psychological, and social perspective. Research indicates that some emerging adults feel it is necessary to engage in hooking-up behavior as part of the sexual script depicted in the culture and media. Additionally, they desire sexual gratification. However, many also want a more committed romantic relationship and may feel regret about uncommitted sex.

Friends with Benefits. Hookups are different from relationships that involve continued mutual exchange. These relationships are often referred to as Friends with Benefits (FWB) or “Booty Calls.” These relationships involve friends having casual sex without commitment. Hookups do not include a friendship relationship. Bisson and Levine (2009) found that 60% of 125 undergraduates reported an FWB relationship. The concern with FWB is that one partner may feel more romantically invested than the other (Garcia et al., 2012).

Committed Relationships

Cohabitation is an arrangement where two people who are not married live together. They often involve a romantic or sexually intimate relationship on a long-term or permanent basis. Such arrangements have become increasingly common in Western countries during the past few decades, being led by changing social views, especially regarding marriage, gender roles, and religion. Today, cohabitation is a common pattern among people in the Western world.

In Europe, the Scandinavian countries have been the first to start this leading trend, although many countries have since followed. Mediterranean Europe has traditionally been very conservative, with religion playing a strong role. Until the mid-1990s, cohabitation levels remained low in this region but have since increased. Cohabitation is common in many countries, with the Scandinavian nations of Iceland, Sweden, and Norway reporting the highest percentages and more traditional countries like India, China, and Japan reporting low percentages (DeRose, 2011).

In countries where cohabitation is increasingly common, there has been speculation as to whether or not cohabitation is now part of the natural developmental progression of romantic relationships: dating and courtship, then cohabitation, engagement, and finally marriage. Though, while many cohabitating arrangements ultimately lead to marriage, many do not.

How prevalent is cohabitation today in the United States? According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2018), cohabitation has been increasing, while marriage has been decreasing in young adulthood. As seen in the graph below, over the past 50 years, the percentage of 18 to 24-year-olds in the U.S. living with an unmarried partner has gone from 0.1 percent to 9.4 percent, while living with a spouse has gone from 39.2 percent to 7 percent. More 18 to 24-year-olds live with an unmarried partner now than with a married partner.

While the percent living with a spouse is still higher than the percent living with an unmarried partner among 25 to 34-year-olds today, the next graph clearly shows a similar pattern of decline in marriage and increase in cohabitation over the last five decades. The percentage living with a spouse in this age group today is only half of what it was in 1968 (40.3 percent vs. 81.5 percent), while the percentage living with an unmarried partner rose from 0.2 percent to 14.8 percent in this age group. Another way to look at some of the data is that only 30% of today’s 18 to 34-year-olds in the U.S. are married, compared with almost double that, 59 percent 40 years ago (1978). The marriage rates for less-educated young adults (who tend to have lower income) have fallen at faster rates than those of better-educated young adults since the 1970s. Past and present economic climate are key factors; perhaps more couples are waiting until they can afford to get married financially. Current (2018) does caution that there are limitations to the measures of cohabitation, particularly in the past.

How long do cohabiting relationships last? Cohabitation tends to last longer in European countries than in the United States. Half of cohabiting relationships in the U. S. end within a year; only 10 percent last more than 5 years. These short-term cohabiting relationships are more characteristics of people in their early 20s. Many of these couples eventually marry. Those who cohabit for more than five years tend to be older and more committed to the relationship. Cohabitation may be preferable to marriage for a number of reasons. For partners over 65, cohabitation is preferable to marriage for practical reasons. For many of them, marriage would result in a loss of Social Security benefits and consequently is not an option. Others may believe that their relationship is more satisfying because they are not bound by marriage.

Cohabitation in Non-Western Cultures, the Philippines and China. Similar to other nations, young people in the Philippines are more likely to delay marriage, cohabitate, and engage in premarital sex as compared to previous generations (Williams et al., 2007). Despite these changes, however, many young people are still not in favor of these practices. Moreover, there is still a persistence of traditional gender norms as there are stark differences in the acceptance of sexual behavior out of wedlock for men and women in Philippine society. Young men are given greater freedom. In China, young adults are cohabitating in higher numbers than in the past (Yu & Xie, 2015). Unlike many Western cultures, in China, adults with higher, rather than lower, levels of education are more likely to cohabitate. Yu and Xie suggest this may be because cohabitation is seen as more “innovative” or “modern” and that those who are more highly educated may have had more exposure to Western cultures.

Think About it

Do you think that you will cohabitate before marriage? Or did you cohabitate? Why or why not? Does your culture play a role in your decision? Does what you learned in this module change your thoughts on this practice?

Engagement and Marriage

Most people will marry in their lifetime. In the majority of countries, 80% of men and women have been married by the age of 49 (United Nations, 2013). Despite how common marriage remains, it has undergone some interesting shifts in recent times. Around the world, people tend to get married later in life or, increasingly, not at all. People in more developed countries (e.g., Nordic and Western Europe), for instance, marry later in life—at an average age of 30 years. This is very different than, for example, the economically developing country of Afghanistan, which has one of the lowest average age statistics for marriage—at 20.2 years (United Nations, 2013). Another shift seen around the world is the gender gap in terms of age when people get married. In every country, men marry later than women. Since the 1970s, the average age of marriage has increased for both women and men.

As illustrated, the courtship process can vary greatly around the world. So, too, can an engagement be a formal agreement to get married? Some of these differences are small, such as on which hand an engagement ring is worn. In many countries, it is worn on the left, but in Russia, Germany, Norway, and India, women wear their rings on their right. There are also more overt differences, such as who makes the proposal. In India and Pakistan, it is not uncommon for the family of the groom to propose to the family of the bride, with little to no involvement from the bride and groom themselves. In most Western industrialized countries, it is traditional for the male to propose to the female. What types of engagement traditions, practices, and rituals are common where you are from? How are they changing?

Contemporary young adults in the United States are waiting longer than before to marry. The median age of entering marriage in the United States is 27 for women and 29 for men (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2011). This trend in delays in young adults taking on adult roles and responsibilities is discussed in our earlier section about “emerging adulthood,” or the transition from adolescence to adulthood, identified by Arnett (2000).

Marriage Worldwide. Cohen (2013) reviewed data assessing most of the world’s countries and found that rates of marriage have declined universally during the last several decades. Although this decline has occurred in both poor and rich countries, the countries with the biggest drops in marriage were mostly rich: France, Italy, Germany, Japan, and the U.S. Cohen argues that these declines are due not only to individuals delaying marriage but also to higher rates of non-marital cohabitation. Delays or decreases in marriage are associated with higher income and lower fertility rates that are observed worldwide.

Marriage Worldwide. Cohen (2013) reviewed data assessing most of the world’s countries and found that rates of marriage have declined universally during the last several decades. Although this decline has occurred in both poor and rich countries, the countries with the biggest drops in marriage were mostly rich: France, Italy, Germany, Japan, and the U.S. Cohen argues that these declines are due not only to individuals delaying marriage but also to higher rates of non-marital cohabitation. Delays or decreases in marriage are associated with higher income and lower fertility rates, which are observed worldwide.

Same-Sex Marriage. In June 26, 2015, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution guarantees same-sex marriage. The decision indicated that limiting marriage to only heterosexual couples violated the 14th amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law. This ruling occurred 11 years after same-sex marriage was first made legal in Massachusetts, and at the time of the high court decision, 36 states and the District of Columbia had legalized same sex marriage. Worldwide, 29 countries currently have national laws allowing gays and lesbians to marry (Pew Research Center, 2019).

Same-sex couples struggle with concerns such as the division of household tasks, finances, sex, and friendships, as do heterosexual couples. One difference between same-sex and heterosexual couples, however, is that same-sex couples have to live with the added stress that comes from social disapproval and discrimination. Continued contact with an ex-partner may be more likely among homosexuals and bisexuals because of the closeness of the circle of friends and acquaintances.

The number of adults who remain single has increased dramatically in the last 30 years. More people who never marry, more widows, and more divorcees are driving up the number of singles. Singles represent about 25 percent of American households. Singlehood has become a more acceptable lifestyle than it was in the past, and many singles are very happy with their status. Whether or not a single person is happy depends on the circumstances of their remaining single.

Cultural Influences on Marriage. Many cultures have both explicit and unstated rules that specify who is an appropriate mate. Consequently, mate selection is not completely left to the individual. Rules of endogamy indicate the groups we should marry within and those we should not (Witt, 2009). For example, many cultures specify that people marry within their own race, social class, age group, or religion. For example, for most of its history, the US upheld laws that criminalized marriage between people from different races; the last such laws were struck down by a Supreme Court ruling in 1967. Endogamy reinforces the cohesiveness of the group. Additionally, these rules encourage homogamy or marriage between people who share social characteristics. The majority of marriages in the U. S. are homogamous with respect to race, social class, age, and, to a lesser extent, religion. Homogamy is also seen in couples with similar personalities and interests.

Arranged Marriages and Elopement. Historically, marriage was not a personal choice but one made by one’s family. Arranged marriages often ensured proper transference of a family’s wealth and the support of ethnic and religious customs. Such marriages were considered marriages of families rather than of individuals. In Western Europe, starting in the 18th century, the notion of personal choice in a marital partner slowly became the norm. Arranged marriages were seen as “traditional,” and marriages based on love as “modern.” Many of these early “love” marriages were accomplished by eloping (Thornton, 2005).

Around the world, more and more young couples are choosing their own partners, even in nations where arranged marriages are still the norm, such as India and Pakistan. Desai and Andrist (2010) found that in India, only 5% of the women they surveyed, aged 25-49, had a primary role in choosing their partner. Only 22% knew their partner for more than one month before they were married. However, the younger cohort of women was more likely to have been consulted by their families before their partner was chosen than the older cohort, suggesting that family views are changing about personal choice. Allendorf (2013) reports that this 5% figure may also underestimate young people’s choices, as only women were surveyed. Many families in India are increasingly allowing sons veto power over the parents’ choice of their future spouse, and some families give daughters the same say.

In some cultures it is not uncommon for the families of young people to do the work of finding a mate for them. For example, the Shanghai Marriage Market refers to the People’s Park in Shanghai, China—a place where parents of unmarried adults meet on weekends to trade information about their children in an attempt to find suitable spouses for them (Bolsover, 2011). In India, the marriage market refers to the use of marriage brokers or marriage bureaus to pair eligible singles together (Trivedi, 2013). To many Westerners, the idea of arranged marriage can seem puzzling. It can appear to take the romance out of the equation and violate values about personal freedom. On the other hand, some people in favor of arranged marriage argue that parents are able to make more mature decisions than young people.

While such intrusions may seem inappropriate based on your upbringing, for many people worldwide, such help is expected, even appreciated. In India, for example, “parental arranged marriages are largely preferred to other forms of marital choices” (Ramsheena & Gundemeda, 2015, p. 138). Of course, one’s religious and social caste plays a role in determining how involved a family may be.

According to the filter theory of mate selection, the pool of eligible partners becomes narrower as it passes through filters used to eliminate members of the pool (Kerckhoff & Davis, 1962). One such filter is propinquity or geographic proximity. Mate selection in the United States typically involves meeting eligible partners face-to-face. Those with whom one does not come into contact are simply not contenders (though this has been changing with the Internet). Race and ethnicity are other filters used to eliminate partners. Although interracial dating has increased in recent years and interracial marriage rates are higher than before, interracial marriage still represents only 5.4 percent of all marriages in the United States. Physical appearance is another feature considered when selecting a mate. Age, social class, and religion are also criteria used to narrow the field of eligibles. Thus, the field of eligibles becomes significantly smaller before those things we are most conscious of, such as preferences, values, goals, and interests, are even considered.

Relationships 101: Predictors of Marital Harmony

Advice on how to improve one’s marriage is centuries old. One of today’s experts on marital communication is John Gottman. Gottman (1999) differs from many marriage counselors in his belief that having a good marriage does not depend on compatibility. Rather, he argues that the way partners communicate with one another is crucial. At the University of Washington in Seattle, Gottman has conducted some of the most thorough and interesting studies of marital relationships. His research team measured the physiological responses of thousands of couples as they discussed issues of disagreement. Fidgeting in one’s chair, leaning closer to or further away from the partner while speaking, and increases in respiration and heart rate are all recorded and analyzed along with videotaped recordings of the partners’ exchanges. Gottman is trying to identify aspects of communication patterns that can accurately predict whether or not a couple will stay together. In marriages destined to fail, partners engage in the “marriage killers”: Contempt, criticism, defensiveness, and stonewalling. Each of these undermines the caring and respect that healthy marriages require. To some extent, all partnerships include some of these behaviors occasionally, but when these behaviors become the norm, they can signal that the end of the relationship is near; for that reason, they are known as “Gottman’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse”. Contempt, which entails mocking or derision and communicating the other partner is inferior, is seen as the worst of the four because it is the strongest predictor of divorce. (Click here for suggestions on diffusing your own contempt.)

Gottman et al. (2000) researched the perceptions newlyweds had about their partner and marriage. The Oral History Interview used in this study, which looks at eight variables in marriage, including Fondness/affection, we-ness, expansiveness/ expressiveness, negativity, disappointment, and three aspects of conflict resolution (chaos, volatility, glorifying the struggle), was able to predict the stability of the marriage (vs. divorce) with 87% accuracy at the four to six year-point and 81% accuracy at the seven to nine year-point. Gottman (1999) developed workshops for couples to strengthen their marriages based on the results of the Oral History Interview. Interventions include increasing positive regard for each other, strengthening their friendship, and improving communication and conflict resolution patterns.

Accumulated Positive Deposits to the “Emotional Bank Account.” When there is a positive balance of relationship deposits this can help the overall relationship in times of conflict. For instance, some research indicates that a husband’s level of enthusiasm in everyday marital interactions was related to a wife’s affection in the midst of conflict (Driver & Gottman, 2004), showing that being friendly and making deposits can change the nature of conflict. Gottman and Levenson (1992) also found that couples rated as having more pleasant interactions, compared with couples with less pleasant interactions, reported higher marital satisfaction, less severe marital problems, better physical health, and less risk for divorce. Finally, Janicki et al. (2006) showed that the intensity of conflict with a spouse predicted marital satisfaction unless there was a record of positive partner interactions, in which case the conflict did not matter as much. Again, it seems as though having a positive balance through prior positive deposits helps to keep relationships strong even in the midst of conflict.

Parenthood

Parenthood is undergoing changes in the United States and elsewhere in the world. Women in the United States have fewer children than they did previously, and children are less likely to be living with both parents. The average fertility rate of women in the United States was about seven children in the early 1900s and has remained relatively stable at 2.1 since the 1970s (Hamilton, Martin, & Ventura, 2011; Martinez, Daniels, & Chandra, 2012). Not only are parents having fewer children, the context of parenthood has also changed. Parenting outside of marriage has increased dramatically among most socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic groups, although college-educated women are substantially more likely to be married at the birth of a child than are mothers with less education (Dye, 2010).

People are having children at older ages, too. This is not surprising given that many of the age markers for adulthood have been delayed, including marriage, completing an education, establishing oneself at work, and gaining financial independence. In 2014, the average age for American first-time mothers was 26.3 years (CDC, 2015). The birth rate for women in their early 20s has declined in recent years, while the birth rate for women in their late 30s has risen. In 2011, 40% of births were to women ages 30 and older. For Canadian women, birth rates are even higher for women in their late 30s than in their early 20s. In 2011, 52% of births were to women ages 30 and older, and the average first-time Canadian mother was 28.5 years old (Cohn, 2013). Improved birth control methods have also enabled women to postpone motherhood. Despite the fact that young people are more often delaying childbearing, most 18- to 29-year-olds want to have children and say that being a good parent is one of the most important things in life (Wang & Taylor, 2011).

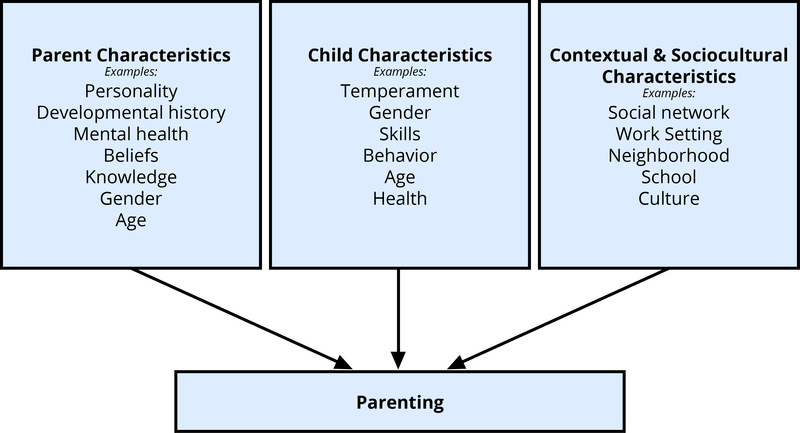

Influences on Parenting. Parenting is a complex process in which parents and children influence one another. There are many reasons that parents behave the way they do. The multiple influences on parenting are still being explored. Proposed influences on parenting include Parent characteristics, child characteristics, and contextual and sociocultural characteristics. (Belsky, 1984; Demick, 1999).

Parent Characteristics. Parents bring unique traits and qualities to the parenting relationship that affect their decisions as parents. These characteristics include the age of the parent, gender, beliefs, personality, developmental history, knowledge about parenting and child development, and mental and physical health. Parents’ personalities affect parenting behaviors. Mothers and fathers who are more agreeable, conscientious, and outgoing are warmer and provide more structure to their children. Parents who are more agreeable, less anxious, and less negative also support their children’s autonomy more than parents who are anxious and less agreeable (Prinzie, Stams, Dekovic, Reijntes, & Belsky, 2009). Parents who have these personality traits appear to be better able to respond to their children positively and provide a more consistent, structured environment for their children.

Parents’ developmental histories, or their experiences as children, also affect their parenting strategies. Parents may learn parenting practices from their own parents. Fathers whose own parents provided monitoring, consistent and age-appropriate discipline, and warmth were more likely to provide this constructive parenting to their own children (Kerr, Capaldi, Pears, & Owen, 2009). Patterns of negative parenting and ineffective discipline also appear from one generation to the next. However, parents who are dissatisfied with their own parents’ approach may be more likely to change their parenting methods with their own children.

Child Characteristics. Parenting is bidirectional. Not only do parents affect their children, but children also influence their parents. Child characteristics, such as gender, birth order, temperament, and health status, affect parenting behaviors and roles. For example, an infant with an easy temperament may enable parents to feel more effective, as they are easily able to soothe the child and elicit smiling and cooing. On the other hand, a cranky or fussy infant elicits fewer positive reactions from his or her parents and may result in parents feeling less effective in the parenting role (Eisenberg et al., 2008). Over time, parents of more difficult children may become more punitive and less patient with their children (Clark, Kochanska, & Ready, 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Kiff, Lengua, & Zalewski, 2011). Parents who have a fussy, difficult child are less satisfied with their marriages and have greater challenges in balancing work and family roles (Hyde, Else-Quest, & Goldsmith, 2004). Thus, child temperament is one of the child characteristics that influences how parents behave with their children.

Another child characteristic is the gender of the child. Parents respond differently to boys and girls. Parents talk differently with their sons and daughters, providing more scientific explanations to their sons and using more emotional words with their daughters (Crowley, Callanan, Tenenbaum, & Allen, 2001). Parents also often assign different household chores to their sons and daughters. Girls are more often responsible for caring for younger siblings and household chores, whereas boys are more likely to be asked to perform chores outside the home, such as mowing the lawn (Grusec, Goodnow, & Cohen, 1996).

Contextual Factors and Sociocultural Characteristics. The parent-child relationship does not occur in isolation. As we discussed in the previous section on families and parenting, parenting is influenced by higher-order sociocultural contexts. Sociocultural characteristics, including economic hardship, religion, politics, neighborhoods, schools, and social support, also influence parenting. Parents who experience economic hardship are more easily frustrated, depressed, and sad, and these emotional characteristics affect their parenting skills (Conger & Conger, 2002).

Culture also influences parenting behaviors in fundamental ways. Although promoting the development of skills necessary to function effectively in one’s community is a universal goal of parenting, the specific skills necessary vary widely from culture to culture. Thus, parents have different goals for their children that partially depend on their culture (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2008). Parents vary in how much they emphasize goals for independence and individual achievements, maintaining harmonious relationships, and being embedded in a strong network of social relationships. Culture is also a contributing contextual factor. For example, Latina mothers who perceived their neighborhood as more dangerous showed less warmth with their children, perhaps because of the greater stress associated with living a threatening environment (Gonzales et al., 2011).

Other important contextual characteristics, such as the neighborhood, school, and social networks, also affect parenting, even though these settings do not always include both the child and the parent (Brofenbrenner, 1989). This would be a good time to go back and re-re the section in Unit 4: Family on higher-order contexts of parenting, and the two papers that examined the ways that poverty and structural racism make parenting more challenging. As you may remember, there are three major ways that status hierarchies, like those organized around class and race, make parenting more difficult:

- Inequities create objective living conditions that are developmentally hazardous to children and families;

- Hardships and discrimination force people to parent under stressful conditions; and

- Families must expend effort to counteract the pervasive effects of discrimination and prejudice on the development of their children and adolescents.

Pay special attention to the recommendations provided in that section about how to make higher-order contexts more supportive of the important jobs of parenting and providing for a family, which are challenging tasks even under the best of circumstances

The many factors that influence parenting are depicted in the following figure.

Concluding thoughts

The new life stage of emerging adulthood has spread rapidly in the past half-century and is continuing to spread. Now that the transition to adulthood is later than in the past, is this change positive or negative for emerging adults and their societies? Certainly, there are some negatives. It means that young people are dependent on their parents for longer than in the past, and they take longer to become fully contributing members of their societies. A substantial proportion of them have trouble sorting through the opportunities available to them and struggle with anxiety and depression, even though most are optimistic. However, there are advantages to having this new life stage as well. By waiting until at least their late twenties to take on the full range of adult responsibilities, emerging adults are able to focus on obtaining enough education and training to prepare themselves for the demands of today’s information- and technology-based economy. Also, it seems likely that if young people make crucial decisions about love and work in their late twenties or early thirties rather than their late teens and early twenties, their judgment will be more mature, and they will have a better chance of making choices that will work out well for them in the long run.

What can societies do to enhance the likelihood that emerging adults will make a successful transition to adulthood? One important step would be to expand the opportunities for obtaining tertiary education. The tertiary education systems of OECD countries were constructed at a time when the economy was much different, and they have not expanded at the rate needed to serve all the emerging adults who need such education. Furthermore, in some countries, such as the United States, the cost of tertiary education has risen steeply and is often unaffordable to many young people. In non-industrialized countries, tertiary education systems are even smaller and less able to accommodate their emerging adults. Across the world, societies would be wise to strive to make it possible for every emerging adult to receive tertiary education free of charge. There could be no better investment for preparing young people for the economy of the future.

Additional Resources

- Article: The People Who Prioritize a Friendship Over Romance – The Atlantic

- What if friendship, and not marriage, was at the center of life?

- The Love Competition

- The World’s First Annual Love Competition. Because “Love is a feeling you have for someone you have feelings about.”

Attributions

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Love, Friendship, and Social Support by Debi Brannan and Cynthia D. Mohr is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Additional written material by Ellen Skinner & Heather Brule, Portland State University, is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

References

Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family Relationships and Support Systems in Emerging Adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 193–217). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11381-008

Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2008). Becoming friends by chance. Psychological Science, 19(5), 439–440.

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55, 83–96.

Birditt, K. S., & Antonucci, T. C. (2007). Relationship quality profiles and well-being among married adults. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 595.

Bisson, M. A., & Levine, T. R. (2009). Negotiating a friends-with-benefits relationship. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(1), 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9211-2

Bolsover, S. R., Shephard, E. A., White, H. A., Hyams, J. S. (2011). Cell biology: A short course (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Bogle, K. A. (2007). The shift from dating to hooking up in college: What scholars have missed: The shift from dating to hooking up. Sociology Compass, 1(2), 775–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00031.x

Bogle, K. A. (2008). Hooking up: Sex, dating, and relationships on campus. New York University Press.

Brannan, D. & Mohr, C. D. (2020). Love, friendship, and social support. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/s54tmp7k

Cacioppo, S., Bianchi-Demicheli, F., Hatfield, E., & Rapson, R. L. (2012). Social neuroscience of love. Clinical Neuropsychiatry: Journal of Treatment Evaluation, 9(1), 3–13.

Carrère, S., Buehlman, K. T., Gottman, J. M., Coan, J. A., & Ruckstuhl, L. (2000). Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 14(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1037//0893-3200.14.1.42

Clark, L. A., Kochanska, G., & Ready, R. (2000). Mothers’ personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 274–285.

Cohen, E. (2007, February 15). Loving with all your … brain. http://www.cnn.com/2007/HEALTH/02/14/love.science/.

Cohn, P. (2013, June 12). Marriage is declining globally. Can you say that? https://familyinequality.wordpress.com/2013/06/12/marriage-is-declining/

Conger, R. D., & Conger, K. J. (2002). Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 361–373.

Crowley, K., Callanan, M. A., Tenenbaum, H. R., & Allen, E. (2001). Parents explain more often to boys than to girls during shared scientific thinking. Psychological Science, 12, 258–261.

Davis, J. L., & Rusbult, C. E. (2001). Attitude alignment in close relationships. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 81(1), 65–84.

Demick, J. (1999). Parental development: Problem, theory, method, and practice. In R. L. Mosher, D. J. Youngman, & J. M. Day (Eds.), Human development across the life span: Educational and psychological applications (pp. 177–199). Westport, CT: Praeger.

DeRose, L. (2011). International family indicators: Global family structure. In The Sustainable Demographic Dividend: What do Marriage and Fertility have to do with the Economy? Charlottesville, VA: The National Marriage Project.

Driver, J., & Gottman, J. (2004). Daily marital interactions and positive affect during marital conflict among newlywed couples. Family Process, 43, 301–314.

Dunn, J. (1984). Sibling studies and the developmental impact of critical incidents. In P.B. Baltes & O.G. Brim (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (Vol 6). Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Dunn, J. (2007). Siblings and socialization. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization. New York: Guilford.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Guthrie, I.K., Murphy, B.C., & Reiser, M. (1999). Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Development, 70, 513-534.

Eisenberg, N., Hofer, C., Spinrad, T., Gershoff, E., Valiente, C., Losoya, S. L., Zhou, Q., Cumberland, A., Liew, J., Reiser, M., & Maxon, E. (2008). Understanding parent-adolescent conflict discussions: Concurrent and across-time prediction from youths’ dispositions and parenting. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 73, (Serial No. 290, No. 2), 1-160.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Feingold, A. (1988). Matching for attractiveness in romantic partners and same-sex friends: A meta-analysis and theoretical critique. Psychological Bulletin, 104(2), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.104.2.226

Finkel, E. J., Burnette, J. L., & Scissors, L. E. (2007). Vengefully ever after: destiny beliefs, state attachment anxiety, and forgiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 871–886. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.871

Fisher, H. E., Brown, L. L., Aron, A., Strong, G., & Mashek, D. (2010). Reward, addiction, and emotion regulation systems associated with rejection in love. Journal of Neurophysiology, 104(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00784.2009

Garcia, J. R., Reiber, C., Massey, S. G., & Merriwether, A. M. (2012). Sexual hookup culture: A review. Review of General Psychology: Journal of Division 1, of the American Psychological Association, 16(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027911

Gottman, J. M. (1999). Couple’s handbook: Marriage Survival Kit Couple’s Workshop. Seattle, WA: Gottman Institute

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: behavior, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(2), 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.63.2.221

Gottman, J. M., Carrere, S., Buehlman, K. T., Coan, J. A., & Ruckstuhl, L. (2000). Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 14(1), 42-58.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623

Grusec, J. E., Goodnow, J. J., & Cohen, L. (1996). Household work and the development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology, 32, 999–1007.

Gurrentz, B. (2018). For young adults, cohabitation is up, marriage is down. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/11/cohabitation-is-up-marriage-is-down.html

Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., & Ventura, S. J. (2011). Births: Preliminary data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports, 60(2). Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Harmon-Jones, E., & Allen, J. J. B. (2001). The role of affect in the mere exposure effect: Evidence from psychophysiological and individual differences approaches. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(7), 889–898.

Hendrick, C., & Hendrick, S. S. (Eds.). (2000). Close relationships: A sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hudson, N. W., Fraley, R. C., Vicary, A. M., & Brumbaugh, C. C. (2012). Attachment coregulation: A longitudinal investigation of the coordination in romantic partners’ attachment styles. Manuscript under review.

Hyde, J. S., Else-Quest, N. M., & Goldsmith, H. H. (2004). Children’s temperament and behavior problems predict their employed mothers’ work functioning. Child Development, 75, 580–594.

Ingram, P., & Morris, M. W. (2007). Do people mix at mixers? Structure, homophily, and the “life of the party”. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(4), 558-585. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.4.558

Janicki, D. L., Kamarck, T. W., Shiffman, S., & Gwaltney, C. J. (2006). Application of ecological momentary assessment to the study of marital adjustment and social interactions during daily life. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 20(1), 168–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.168

Joost, H., & Schulman, A. (2010). Catfish. Rogue.

Kaufman, B. E., & Hotchkiss, J. L. 2003. The economics of labor markets (6th ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western.

Kerckhoff, A. C., & Davis, K. E. (1962). Value consensus and need complementarity in mate selection. American Sociological Review, 27(3), 295-303. https://doi.org/10.2307/2089791

Kerr, D. C. R., Capaldi, D. M., Pears, K. C., & Owen, L. D. (2009). A prospective three generational study of fathers’ constructive parenting: Influences from family of origin, adolescent adjustment, and offspring temperament. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1257–1275.

Klenke-Hamel, K., & Janda, L. H. (1980). Human sexuality. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Levine, D. (2000). Virtual attraction: What rocks your boat. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 3(4), 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1089/109493100420179

Madden, M., & Lenhart, A. (2006). Online dating. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Retrieved from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/628767/online-dating/1610084/

Martinez, G., Daniels, K., & Chandra, A. (2012). Fertility of men and women aged 15-44 years in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006-2010. National Health Statistics Reports, 51(April). Hyattsville, MD: U.S., Department of Health and Human Services.

Masci, D., Sciupac, E. P., & Lipka, M. (2019). Same-Sex Marriage Around the World. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/fact-sheet/gay-marriage-around-the-world/

McCann Hamilton, V. (2007). Human relations: The art and science of building effective relationships. Prentice Hall.

McCann, V. (2016). Human relations: The art and science of building effective relationships, books a la carte (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Mckillip, J., & Redel, S. L. (1983). External validity of matching on physical attractiveness for same and opposite sex Couples1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 13(4), 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1983.tb01743.x

Moreland, R. L., & Beach, S. R. (1992). Exposure effects in the classroom: The development of affinity among students. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 28(3), 255-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(92)90055-O

Prinzie, P., Stams, G. J., Dekovic, M., Reijntjes, A. H., & Belsky, J. (2009). The relations between parents’ Big Five personality factors and parenting: A meta-review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 351–362.

Ramsheena, C. A. (2015). Youth and marriage: A study of changing marital choices among the university students in India. Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 06(01). https://doi.org/10.31901/24566764.2015/06.01.11

Reis, H. T., & Aron, A. (2008). Love: What is it, why does it matter, and how does it operate? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(1), 80–86.

Schindler, I., Fagundes, C. P., & Murdock, K. W. (2010). Predictors of romantic relationship formation: Attachment style, prior relationships, and dating goals. Personal Relationships, 17, 97-105.

Simpson, J. A., Collins, W. A., Tran, S., & Haydon, K. C. (2007). Attachment and the experience and expression of emotions in adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 355–367.

Simpson, J. A., Rholes, W. S., Oriña, M. M., & Grich, J. (2002). Working models of attachment, support giving, and support seeking in a stressful situation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 598-608.

Sorokowski, P., Randall, A. K., Groyecka, A., Frackowiak, T., Cantarero, K., Hilpert, P., Ahmadi, K., Alghraibeh, A. M., Aryeetey, R., Bertoni, A., Bettache, K., Blazejewska, M., Bodenmann, G., Bortolini, T. S., Bosc, C., Butovskaya, M., Castro, F. N., Cetinkaya, H., Cunha, D., David, D., David, O. A., Espinosa, A. C. D., Donato, S., Dronova, D., Dural, S., Fisher, M., Akkaya, A. H., Hamamura, T., Hansen, K., Hattori, W. T., Hromatko, I., Gulbetekin, E., Iafrate, R., James, B., Jiang, F., Kimamo, C. O., Koç, F., Krasnodebska, A., Laar, A., Lopes, F. A., Martinez, R., Mesko, N., Molodovskaya, N., Qezeli, K. M., Motahari, Z., Natividade, J. C., Ntayi, J., Ojedokun, O., Mohd, M. S., Onyishi, I. E., Özener, B., Paluszak, A., Portugal, A., Realo, A., Relvas, A. P., Rizwan, M., Sabiniewicz, A. L., Salkicevic, S., Sarmány-Schuller, I., Stamkou, E., Stoyanova, S., Šukolová, D., Sutresna, N., Tadinac, M., Teras, A., Edna, E. L., Tripathi, R., Tripathi, N., Tripathi, M., Yamamoto, M. E., Yoo, G., & Sorokowska, A. (2017). Marital satisfaction, sex, age, marriage duration, religion, number of children, economic status, education, and collectivistic values: Data from 33 countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1199. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01199

Sternberg, R. J. (2004). A Triangular Theory of Love. In H. T. Reis & C. E. Rusbult (Eds.), Close relationships: Key readings (pp. 213–227). Taylor & Francis.

Sternberg, R. J. (2007). Triangulating Love. In Oord, T. J. The Altruism Reader: Selections from Writings on Love, Religion, and Science (pp 331-347). West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation.

Tannen, D. (1990). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. New York: Morrow.

Taylor, L. S., Fiore, A. T., Mendelsohn, G. A., & Cheshire, C. (2011). “Out of my league”: a real-world test of the matching hypothesis. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(7), 942–954. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211409947

Thornton, A. (2005). Reading history sideways: The fallacy and enduring impact of the developmental paradigm on family life. University of Chicago Press.

Trivedi, A. (2013). In New Delhi, women marry up, and men are left behind. The New York Times. http://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/15/in-delhi-women-marry-up-and-men-are-left-behind

United Nations (2013). World Marriage Data 2012. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/WMD2012/MainFrame.html

US Census Bureau. (2022, November 15). Living with an unmarried partner now common for young adults. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/11/cohabitation-is-up-marriage-is-down-for-young-adults.html

Wang, W., & Parker, K. (2014). Record share of Americans have never married: As values, economics and gender patterns change. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2014/09/2014-09-24_NeverMarried-Americans.pdf

Wang, W., & Taylor, P. (2011). For Millennials, parenthood trumps marriage. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2011/03/09/for-millennials-parenthood-trumps-marriage/

Welsh, D. P., Grello, C. M., & Harper, M. S. (2006). No strings attached: the nature of casual sex in college students. Journal of Sex Research, 43(3), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490609552324

Witt, J. (2010). SOC (2010th ed.). McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages.

Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2015). Cohabitation in China: Trends and determinants. Population and Development Review, 41(4), 607–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00087.x

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2, Pt.2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025848

Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. The American Psychologist, 35(2), 151–175. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.35.2.151