Section 6: Early Childhood

6.2 Cognitive Development in Early Childhood

What’s cognitive growth like in early childhood?

Early childhood is a time of pretending, blending fact and fiction, and learning to think of the world using language. As young children move away from needing to touch, feel, and hear about the world toward learning basic principles about how the world works, they hold some pretty interesting initial ideas. For example, how many of you are afraid that you are going to go down the bathtub drain? Hopefully, none of you! But a child of three might really worry about this as they sit at the front of the bathtub. A child might protest if told that something will happen “tomorrow” but be willing to accept an explanation that an event will occur “today after we sleep.” Or the young child may ask, “How long are we staying? From here to here?” while pointing to two points on a table. Concepts such as tomorrow, time, size, and distance are not easy to grasp at this young age. Understanding size, time, distance, fact, and fiction are all tasks that are part of cognitive development in the preschool years.

Early childhood is a time of pretending, blending fact and fiction, and learning to think of the world using language. Young children move away from needing to touch, feel, and hear about the world toward learning basic principles about how the world works, they hold some pretty interesting initial ideas. For example, a three-year-old child might worry about whether or not they will go down the drain with the water in the bathtub. A child might protest if told that something will happen “tomorrow” but be willing to accept an explanation that an event will occur “today after we sleep.” Concepts such as tomorrow, time, size, fact, fiction, and distance are all tasks typically part of cognitive development during the preschool years.

Learning Objectives

- Describe Piaget’s preoperational stage of development

- Illustrate limitations in early childhood thinking, including animism, egocentrism, and conservation errors

- Explain theory-theory and theory of mind

- Explain language development and the importance of language in early childhood

- Describe Vygotsky’s model, including the zone of proximal development

- Compare preschool education programs and their developmental impacts

Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

| Table 1. Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development | |||

| Age (years) | Stage | Description | Developmental issues |

| 0–2 | Sensorimotor | World experienced through senses and actions | Object permanence Stranger anxiety |

| 2–7 | Preoperational | Use words and images to represent things but lack logical reasoning | Pretend play Egocentrism Language development |

| 7–11 | Concrete operational | Understand concrete events and logical analogies; perform arithmetical operations | Conservation Mathematical transformations |

| 11– | Formal operational | Utilize abstract reasoning and hypothetical thinking | Abstract logic Moral reasoning |

Piaget’s Second Stage: The Preoperational Stage

Piaget believed that we are continuously trying to maintain balance in how we understand the world. With rapid increases in motor skills and language development, young children are constantly encountering new experiences, objects, and words. When faced with something new, a child may either assimilate (bringing in new information) it into an existing schema by matching it with something they already know or expand their knowledge structure to accommodate (change the new learning) the new situation. During the preoperational stage, many of the child’s existing schemas will be challenged, expanded, and rearranged. Their whole view of the world may shift.

Piaget’s second stage of cognitive development is called the preoperational stage and coincides with ages 2-7 (following the sensorimotor stage). The word operational refers to the use of logical manipulation of information, so children at this stage are considered pre-operational. Sometimes this stage is misinterpreted as implying that children are illogical. While it is true that children at the beginning of the preoperational stage tend to answer questions intuitively as opposed to logically, children in this stage are learning to use language and how to think about the world symbolically (symbolic thought). These skills help children develop the foundations they will need to consistently use operations in the next stage. Let’s examine some of Piaget’s assertions about children’s cognitive abilities at this age.

Pretend Play

Pretend play is typically a favorite activity at this time. For a child in the preoperational stage, a toy has qualities beyond the way it was designed to function and can now be used to stand for a character or object unlike anything originally intended. A laundry basket, for example, can be a boat or flip over to be the shell of a turtle or hermit crab!

Piaget believed that children’s pretend play and experimentation helped them solidify the new schemas they were developing cognitively. This involves both assimilation and accommodation, which results in changes in their conceptions or thoughts for future logical operations. However, children also learn as they pretend and experiment. Their play does not simply represent what they have learned (Berk, 2007).

Symbolic representation

In addition to ushering in an era of pretend play, the development of symbolic representation revolutionizes the way young children think and act. Representational capacities underlie the emergence of language, which opens up channels of communication with others and provides young children with words and concepts for their inner experiences (like emotion labels). Symbolic capacities also scaffold the development of memory and allow young children to remember and discuss autobiographical events. They become very interested in two-dimensional representations, like photographs and computer screens, and can interact with grandparents and others using these tools.

As seen at the end of the sensorimotor period, toddlers begin to use primitive representations to solve problems in their heads. During the preschool years, cognitive advances allow them to get better and better at trying out strategies mentally before taking action. Hence, planning and problem-solving become central activities. Problem-solving can be used to facilitate physical play (e.g., planning how to build a castle), solve interpersonal conflicts (e.g., two children want the same toy), or figure out how to comfort oneself when one is sad.

Mental representations are also key to the advances in executive function and self-regulation described earlier. When children can hold goals in their minds that are different from the ones that spontaneously emerge, they use representations of what they are supposed to do to modulate or manage what they want to do. Young children show an outpouring of representational activities, including language, pretend play, storytelling, singing, drawing, looking at photos, and discussing the past and present. They love to engage in joint problem-solving and be read to, often asking for the same book or video over and over again, pouring over and discussing the story until they can repeat every word.

Despite the many advances that symbolic thought brings to young children, there are still several significant limitations to their thinking, as described below. When parents see behaviors typical of the preoperational stage, it is important that they correctly interpret their meaning. Young children are not being hard to get along with. These behaviors are the result of genuine limitations in their cognitive functioning. Young children can understand many ideas and follow rules, but for the best developmental outcomes, adults should temper their expectations and demands so that they are reasonable and explain their thinking using language that is developmentally attuned to children’s current cognitive capacities.

Egocentrism

Egocentrism in early childhood refers to the tendency of young children not to be able to take the perspective of others, and instead, the child thinks that everyone sees, thinks, and feels just as they do. Egocentric children are not able to infer the perspective of other people and instead attribute their own perspective to everyone in the situation. For example, ten-year-old Keiko’s birthday is coming up, so her mom takes 3-year-old Kenny to the toy store to choose a present for his sister. He selects an Iron Man action figure for her, thinking that if he likes the toy, his sister will too.

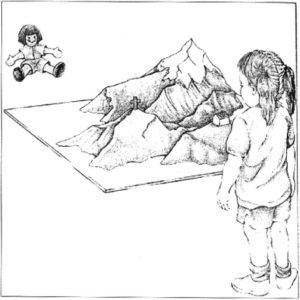

Piaget’s classic experiment on egocentrism involved showing children a three-dimensional model of a mountain and asking them to describe what a doll that is looking at the mountain from a different angle might see (see Figure 1). Children tend to choose a picture that represents their own rather than the doll’s view. By age 7, children are less self-centered. However, even younger children, when speaking to others, tend to use different sentence structures and vocabulary when addressing a younger child or an older adult. This indicates some awareness of the views of others. Consider why this difference might be observed. Do you think this indicates some awareness of the views of others? Or do you think they are simply modeling adult speech patterns?

The children in this interview display egocentrism by believing that the researcher sees the same thing as they do, even after switching positions.

This video demonstrates that older children are able to look at the mountain from different viewpoints and no longer fall prey to egocentrism.

You can view the transcript for “Piaget’s Mountains Task” here (opens in new window).

Precausal Thinking

Similar to preoperational children’s egocentric thinking is their structuring of cause-and-effect relationships based on their limited view of the world. Piaget coined the term “pre-causal thinking” to describe the way in which preoperational children use their own existing ideas or views, like in egocentrism, to explain cause-and-effect relationships. Three main concepts of causality, as displayed by children in the preoperational stage, include animism, artificialism, and transductive reasoning.

Animism refers to attributing life-like qualities to objects. An example could be a child believing that the sidewalk was mad and made them fall down or that the stars twinkle in the sky because they are happy. To an imaginative child, the cup may be alive, the chair that falls down and hits the child’s ankle is mean, and the toys need to stay home because they are tired. They may believe that stuffed animals and objects have feelings just as they do. Young children do seem to think that objects that move may be alive, but after age three, they seldom refer to objects as being alive (Berk, 2007). Many children’s stories and movies capitalize on animistic thinking. Do you remember some of the classic stories that make use of the idea of objects being alive and engaging in lifelike actions?

Artificialism refers to the belief that environmental characteristics can be attributed to human actions or interventions. For example, a child might say that it is windy outside because someone is blowing very hard, or the clouds are white because someone painted them that color.

Finally, precausal thinking is categorized by transductive reasoning.

Preoperational children also demonstrate centration when they have difficulty understanding that an object can be classified in more than one way. Transductive reasoning is when a child fails to understand the true relationships between cause and effect. For example, if shown three white buttons and four black buttons and asked whether there are more black buttons or buttons, the child is likely to respond that there are more black buttons. They focus on the most salient feature (black buttons) and cannot keep in mind the general class of buttons, so they compare black versus white buttons instead of part versus whole. Because young children lack these general classes, their reasoning is typically transductive, that is, making faulty inferences from one specific example to another. For example, Piaget’s daughter Lucienne stated she had not had her nap, therefore it was not afternoon. She did not understand that afternoons are a time period, and her nap was just one of many events that occurred in the afternoon (Crain, 2005). As the child’s capacity to mentally represent and coordinate multiple features improves, the ability to classify objects emerges.

Cognition Errors

Between the ages of four and seven, children tend to become very curious and ask many questions, beginning the use of primitive reasoning. There is an increase in curiosity in the interest of reasoning and wanting to know why things are the way they are. Piaget called it the “intuitive substage” because children realize they have a vast amount of knowledge, but they are unaware of how they acquired it. This is an age filled with questions as children begin to make sense of their worlds. Parents should know that children’s ceaseless “why?” questions do not require detailed explanations. They are looking for brief and simple explanations. For example, if children ask “Why do I have to wear a helmet when I ride a bicycle?” they are not looking for a lecture on legal issues, but just a simple “To keep your head safe.”

Centration. The primary limitation of thought during the intuitive substage is called centration. Centration means that understanding is dominated (i.e., centered on) a single feather– the most perceptually salient one. At this age, children cannot hold or coordinate two features of an object at the same time. Piaget demonstrated this aspect of preoperational thought in a series of experiments. They showed that young children do not yet have the logical notion of conservation, which refers to the ability to recognize that aspects like quantity remain the same, even when over transformations in appearance.

Inability to conserve. Children at this stage are unaware of conservation and exhibit centration. Imagine a 2-year-old and a 4-year-old eating lunch. The 4-year-old has a whole peanut butter and jelly sandwich. He notices, however, that his younger sister’s sandwich is cut in half and protests, “She has more!” He is exhibiting centration by focusing on the number of pieces, which results in a conservation error.

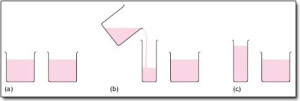

The classic Piagetian experiment associated with conservation involves liquid (Crain, 2005). As seen on the left side of Figure 5.3, the child is shown two glasses that are filled to the same level and asked if they have the same amount. Usually the child agrees they have the same amount. The experimenter then pours the liquid in one glass into a taller and thinner glass (as shown in the center of Figure 3). The child is again asked if the two glasses have the same amount of liquid. The preoperational child will typically say the taller glass now has more liquid because it is taller (as shown on the right side). The child has centrated on the height of the glass and fails to conserve.

Irreversibility is also demonstrated during this stage and is closely related to the ideas of centration and conservation. Irreversibility refers to the young child’s difficulty mentally reversing a sequence of events. In the beaker situation, the child does not realize that if the liquid was poured back into the original beaker, then the same amount of liquid would exist.

Centration, conservation errors, and irreversibility are indications that young children are reliant on visual representations. Another example of children’s reliance on visual representations is their misunderstanding of “less than” or “more than”. When two rows containing equal amounts of blocks are placed in front of a child, with one row spread farther apart than the other, the child will think that the row spread farther contains more blocks. When something takes up more space, it is seen as having more.

This clip shows how younger children struggle with the concept of conservation and demonstrate irreversibility.

Class inclusion refers to a kind of conceptual thinking that children in the preoperational stage cannot yet grasp. Children’s inability to focus on two aspects of a situation at once (centration) inhibits them from understanding the principle that one category or class can contain several different subcategories or classes. Preoperational children also have difficulty understanding that an object can be classified in more than one way. For example, a four-year-old girl may be shown a picture of eight dogs and three cats. The girl knows what cats and dogs are, and she is aware that they are both animals. However, when asked, “Are there more dogs or more animals?” she is likely to answer “more dogs.” This is due to her difficulty focusing on the two subclasses and the larger class all at the same time. She may have been able to view the dogs as dogs or animals, but struggled when trying to classify them as both, simultaneously. Similar to this is a concept relating to intuitive thought, known as “transitive inference.”

Transitive inference is using previous knowledge to determine the missing piece, using basic logic. Children in the preoperational stage lack this logic. An example of transitive inference would be when a child is presented with the information “A” is greater than “B” and “B” is greater than “C.” The young child may have difficulty understanding that “A” is also greater than “C” unless clearly defined.

As the child’s vocabulary improves and more schemes are developed, they are more able to think logically, demonstrate an understanding of conservation, and classify objects.

Was Piaget Right?

It certainly seems that children in the preoperational stage make the mistakes in logic that Piaget suggests that they will make. That said, it is important to remember that there is variability in terms of the ages at which children reach and exit each stage. Further, there is some evidence that children can be taught to think in more logical ways far before the end of the preoperational period. For example, as soon as a child can reliably count, they may be able to learn conservation of number. For many children, this is around age five. More complex conservation tasks, however, may not be mastered until closer to the end of the stage, around age seven.

Critique of Piaget. Similar to the critique of the sensorimotor period, several psychologists have attempted to show that Piaget also underestimated the intellectual capabilities of the preoperational child. For example, children’s specific experiences can influence when they are able to conserve. Children of pottery makers in Mexican villages know that reshaping clay does not change the amount of clay at much younger ages than children who do not have similar experiences (Price-Williams, Gordon, & Ramirez, 1969). Crain (2005) also showed that under certain conditions, preoperational children can think rationally about mathematical and scientific tasks, and they are not always as egocentric as Piaget implied. Research on the theory of mind (discussed later in the chapter) shows that some children overcome egocentrism by 4 or 5 years of age, which is sooner than Piaget indicated. As with sensorimotor development, Piaget seemed to be right about the exact sequence and the processes involved in cognitive development, as well as when these steps are typically observable under naturalistic conditions. However, current research has provided more accurate estimates of the exact ages when underlying capacities emerge, which could only be revealed by working with children in specific experimental conditions that removed barriers to their performance.

Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory: Changes in Thought with Guidance

Modern social learning theories stem from the work of Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky, who produced his ideas as a reaction to existing conflicting approaches in psychology (Kozulin, 1990). Vygotsky’s ideas are most recognized for identifying the role of social interactions and culture in the development of higher-order thinking skills. His theory is especially valuable for the insights it provides about the dynamic “interdependence between individual and social processes in the construction of knowledge” (John-Steiner & Mahn, 1996, p. 192). Vygotsky’s views are often considered primarily as developmental theories, focusing on qualitative changes in behavior over time, that attempt to explain unseen processes of development in thought, language, and higher-order thinking skills. Although Vygotsky’s intent was mainly to understand higher psychological processes in children, his ideas have many practical applications for learners of all ages.

Three themes are often identified with Vygotsky’s ideas of sociocultural learning: (1) human development and learning originate in social, historical, and cultural interactions, (2) the use of psychological tools, particularly language, mediates the development of higher mental functions, and (3) learning occurs within the Zone of Proximal Development. While we discuss these ideas separately, they are closely interrelated.

Sociocultural theory

Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and social interaction in the development of cognitive abilities. Vygotsky contended that thinking has social origins, social interactions play a critical role, especially in the development of higher-order thinking skills, and cognitive development cannot be fully understood without considering the social and historical context within which it is embedded. He explained, “Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level, and later, on the individual level; first between people (interpsychological) and then inside the child (intrapsychological)” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 57). It is through working with others on a variety of tasks that a learner adopts socially shared experiences and associated effects and acquires useful strategies and knowledge (Scott & Palincsar, 2013).

Rogoff (1990) refers to this process as guided participation, where a learner actively acquires new culturally valuable skills and capabilities through a meaningful, collaborative activity with an assisting, more experienced other. It is critical to notice that these culturally mediated functions are viewed as being embedded in sociocultural activities rather than being self-contained. Development is a “transformation of participation in a sociocultural activity,” not a transmission of discrete cultural knowledge or skills (Matusov, 2015, p. 315). For example, young children learn problem-solving skills, not by sitting alone at a desk trying to solve arbitrary problems but by working alongside parents or older siblings as they work on actual culturally relevant tasks, like preparing a family meal or repairing a fence. Working together, the dyad or group encounters social or physical problems and discusses their possible solutions before taking action. Through participation in joint problem-solving, young children develop these skills.

Language as a developmental tool.. In his sociocultural view of development, Vygotsky highlighted the tools that the culture provides to support the development of higher-order thought. Chief among them is language. For Vygotsky, children interact with the world through the tool of language. For Piaget, children use schemas that they construct and organize on the mental plane, but for Vygotsky, language, a social medium, was the mechanism through which we build knowledge of the world. He believed that with development, the language we acquire from our environment shapes the ways in which we think and behave. With development, language becomes internalized as thought (i.e., cognition or reasoning), and children use this internalized language to guide their action.

Scaffolding and the “Zone of Proximal Development.”

Vygotsky differed from Piaget in that he believed that a person not only has a set of actual abilities but also a set of potential abilities that can be realized if given the proper guidance from others. He believed that through guided participation, known as scaffolding, with a teacher or capable peer, a child can learn cognitive skills within a certain range, known as the zone of proximal development. Both Piaget and Vygotsky highlighted the importance of interactions with the social and physical world as the sources of developmental change; Piaget’s ideas of cognitive development emphasized universal stages progressing toward increasing cognitive complexity. Vygotsky presents a more culturally-embedded view in which situated participatory learning drives development. The idea of learning driving development, rather than being determined by the developmental level of the learner, fundamentally changes our understanding of the learning process and has significant instructional and educational implications (Miller, 2011).

Have you ever taught a child to perform a task? Maybe it was brushing their teeth or preparing food. Chances are you spoke to them and described what you were doing while you demonstrated the skill and let them work along with you throughout the process. You gave them assistance when they seemed to need it, but once they knew what to do, you stood back and let them go. This is scaffolding. This approach to teaching has also been adopted by educators. Rather than assessing students on what they are doing, they should be understood in terms of what they are capable of doing with the proper guidance and mentoring.

This difference in assumptions has significant implications for the design and development of learning experiences. If we believe, as Piaget did, that development precedes learning, then we will introduce children to learning activities involving new concepts and problems but follow their lead, allowing learners to initiate participation when they are ready or interested. On the other hand, if we believe, as Vygotsky did, that learning drives development and that development occurs as we learn a variety of concepts and principles, recognizing their applicability to new tasks and new situations, then our instructional design will look very different.

Vygotsky and Education

Vygotsky’s theories do not just apply to language development but have been extremely influential for education in general. Although Vygotsky himself never mentioned the term scaffolding, it is often credited to him as a continuation of his ideas pertaining to the way adults or other children can use guidance in order for a child to work within their ZPD. (The term scaffolding was first developed by Jerome Bruner, David Wood, and Gail Ross while applying Vygotsky’s concept of ZPD to various educational contexts.)

Educators often apply these concepts by assigning tasks that students cannot do on their own but which they can do with assistance; they should provide just enough assistance so that students learn to complete the tasks independently and then provide an environment that enables students to do harder tasks than would otherwise be possible. Teachers can also allow students with more knowledge to assist students who need more guidance. Especially in the context of collaborative learning, group members who have higher levels of understanding can help the less advanced members learn within their zone of proximal development.

Information Processing

Information processing researchers have focused on several issues in cognitive development for this age group, including improvements in attention skills, changes in capacity, and the emergence of executive functions in working memory. Additionally, in early childhood memory strategies, memory accuracy and autobiographical memory emerge. Many researchers see early childhood as a crucial time period in memory development (Posner & Rothbart, 2007) and making sense of the world.

Attention

Young children (age 3-4) have considerable difficulties in dividing their attention between two tasks, and often perform at levels equivalent to our closest relative, the chimpanzee, but by age five they have surpassed the chimp (Hermann et al., 2015; Hermann & Tomasello, 2015). Despite these improvements, 5-year-olds continue to perform below the level of school-age children, adolescents, and adults.

Children’s ability with selective attention improves as they age. Guy et al. (2013) found that children’s ability to selectively attend to visual information outpaced that of auditory stimuli. This may explain why young children are not able to hear the voice of the preschool teacher over the cacophony of sounds in the typical preschool classroom (Jones et al., 2015). Young children between 3 and 7 also have more difficulty sustaining their attention when there are multiple distractions (Berwid et al., 2005).

Memory

Memory dramatically improves in early childhood compared to infancy, but it’s not quite at the level of school-aged children. Children form more detailed autobiographical memories of events from their lives. Most adults don’t remember events from the first few years of their lives, but they can remember events from early childhood.

Young children are less developed in each aspect of memory. They hold sounds for less time in sensory memory than older children and adults (Gomes et al., 1999). A 5-year-old’s working memory is limited to about 4 digits, compared to the 7 digits available to teens and adults. Most kindergarteners do not use strategies to help them remember information (Schneider et al., 2009). More useful strategies emerge in school-aged kids.

More recently, information processing researchers have added to this understanding by examining how children organize information and develop their own theories about the world.

Theory Theory

The tendency of children to generate theories to explain everything they encounter is called theory-theory. This concept implies that humans are naturally inclined to find reasons and generate explanations for why things occur. Children frequently ask questions about what they see or hear around them. When the answers provided do not satisfy their curiosity or are too complicated for them to understand, they generate their own theories. In much the same way that scientists construct and revise their theories, children do the same with their intuitions about the world as they encounter new experiences (Gopnik & Wellman, 2012). One of the theories they start to generate in early childhood centers on the mental states, both their own and those of others.

Theory of Mind

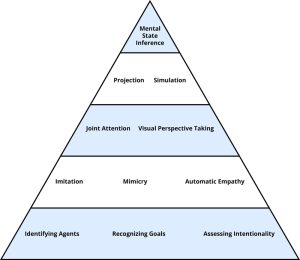

How do we come to understand how our mind works? Theory of mind refers to the understanding that other people experience mental states (for instance, thoughts, beliefs, feelings, or desires) that are different from our own and that their mental states guide their behavior. This skill, which emerges in early childhood, helps humans infer, predict, and understand the reactions of others, thus playing a crucial role in social development and in promoting competent social interactions.

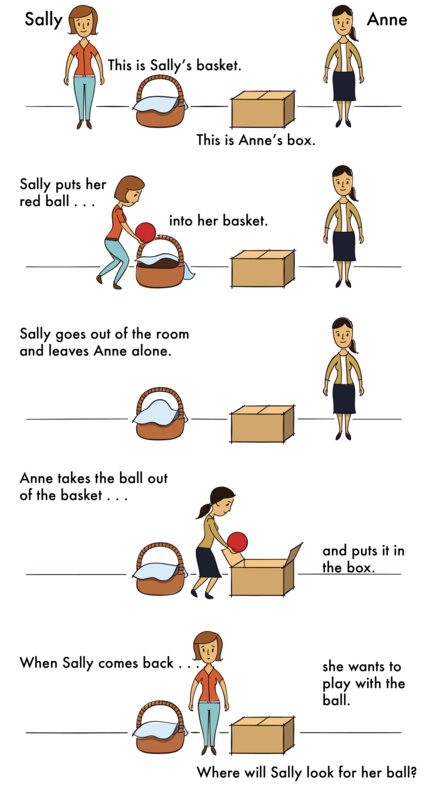

One common method for determining if a child has reached this mental milestone is called the false belief task. The research began with a clever experiment by Wimmer and Perner (1983), who tested whether children could pass a false-belief test (see Figure 5.5). The child is shown a picture story of Sally, who puts her ball in a basket and leaves the room. While Sally is out of the room, Anne comes along, takes the ball from the basket, and puts it inside a box. The child is then asked where Sally thinks the ball is located when she comes back to the room. Is she going to look first in the box or in the basket? The right answer is that she will look in the basket because that is where she put it and thinks it is, but we have to infer this false belief against our own better knowledge that the ball is in the box. This is very difficult for children before the age of four because of the cognitive effort it takes.

Three-year-olds have difficulty distinguishing between what they once thought was true and what they now know to be true. They feel confident that what they know now is what they have always known (Birch & Bloom, 2003). You could say that their perspectives are fused: whatever is actually true is what they and everyone else think. Even adults need to think through this task (Epley, Morewedge, & Keysar, 2004). To be successful at solving this type of task, the child must separate three things: (1) what is true; (2) what they themselves think (which can be false); and (3) what someone else thinks (which can be different from what they think as well as different from reality). Can you see why this task is so complex?

In Piagetian terms, children must give up a tendency toward egocentrism. The child must also understand that what guides people’s actions and responses is what they believe rather than what is actually true. In other words, people can mistakenly believe things that are false (called false beliefs) and will act based on this false knowledge. Consequently, prior to age four, children are rarely successful at solving such tasks (Wellman, Cross & Watson, 2001).

Researchers examining the development of the theory of mind have been concerned by the overemphasis on the mastery of false belief as the primary measure of whether a child has attained a theory of mind. Two-year-olds understand the diversity of desires, yet as noted earlier, it is not until age four or five that children grasp false beliefs, and often not until middle childhood do they understand that people may hide how they really feel. In part, this is because children’s understanding is fused: in early childhood, children do not differentiate genuine feelings from the expression of feelings. They have difficulty hiding how they really feel (e.g., saying thank you for a gift they do not really like). Wellman and his colleagues (Wellman, Fang, Liu, Zhu & Liu, 2006) suggest that the theory of mind is comprised of a number of components, each with its own developmental timeline.

Table 1 Components of Theory of Mind

| Stage, Component | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Desire Psychology (ages 2-3) | ||

| Diverse-desires | Understanding that two people may have different desires regarding the same object. | |

| Belief Psychology (ages 3 or 4 to 5) | ||

| Diverse-beliefs | Understanding that two people may hold different beliefs about an object. | |

| Knowledge access (knowledge/ignorance) | Understanding that people may or may not have access to information. | |

| False belief | Understanding that someone might hold a belief based on false information. | |

adapted from Lally & Valentine-French, 2019

Those in early childhood in the US, Australia, and Germany develop the theory of mind in the sequence outlined in Table 1. Yet, Chinese and Iranian preschoolers acquire knowledge access before diverse beliefs (Shahaeian, Peterson, Slaughter & Wellman, 2011). Shahaeian and colleagues suggested that cultural differences in child-rearing may account for this reversal. Parents in collectivistic cultures, such as China and Iran, emphasize conformity to the family and cultural values, greater respect for elders, and the acquisition of knowledge and academic skills more than they do autonomy and social skills (Frank, Plunkett & Otten, 2010). This could reduce the degree of familial conflict of opinions expressed in the family. In contrast, individualistic cultures encourage children to think for themselves and assert their own opinions, and this could increase the risk of conflict in beliefs being expressed by family members. As a result, children in individualistic cultures would acquire insight into the question of diversity of belief earlier, while children in collectivistic cultures would acquire knowledge access earlier in the sequence. The role of conflict in aiding the development of the theory of mind may account for the earlier age of onset of an understanding of false belief in children with siblings, especially older siblings (McAlister & Petersen, 2007; Perner, Ruffman & Leekman, 1994).

Theory of Mind and Social Intelligence

This awareness of the existence of the mind is part of social intelligence and the ability to recognize that others can think differently about situations. It helps us to be self-conscious or aware that others can think of us in different ways, and it helps us to be able to be understanding or empathetic toward others. This developing social intelligence helps us to anticipate and predict the actions of others (even though these predictions are sometimes inaccurate). The awareness of the mental states of others is important for communication and social skills. A child who demonstrates this skill is able to anticipate the needs of others.

The list of social interactions that rely deeply on theory of mind is long; here are a few highlights.

- Teaching another person new actions or rules involves considering what the learner knows or doesn’t know and how best to make him understand.

- Learning the words of a language by monitoring what other people attend to and are trying to do when they use certain words.

- Figuring out our social standing by trying to guess what others think and feel about us.

- Sharing experiences by telling a friend how much we liked a movie or by showing her something beautiful.

- Collaborating on a task by signaling to one another that we share a goal and understand and trust the other’s intention to pursue this joint goal. (Malle, 2024)

Autism and Impaired Theory of Mind

Individuals with autism can have a harder time using the theory of mind because it involves processing facial expressions and inferring people’s intentions. A look that might convey a lot of meaning to most people conveys little or nothing to someone with autism. People with autism or an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) typically show an impaired ability to recognize other people’s minds. Autism is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction across multiple contexts, as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities.

Children with this disorder typically show signs of significant disturbances in three main areas:

(a) deficits in social interaction,

(b) deficits in communication, and

(c) repetitive patterns of behavior or interests.

These disturbances tend to be present in early childhood, typically before age three, and may lead to clinically significant functional impairment. Symptoms may include lack of social or emotional reciprocity, stereotyped and repetitive language use or idiosyncratic language, and persistent preoccupation with unusual objects.

About half of parents of children with ASD notice their child’s unique behaviors by age 18 months, and about four-fifths notice by age 24 months, but often a diagnosis comes later, and individual cases vary significantly. Typical early signs of autism include:

- No babbling by 12 months.

- No gesturing (pointing, waving, etc.) by 12 months.

- No single words by 16 months.

- No two-word (spontaneous, not just echolalic) phrases by 24 months.

- Loss of any language or social skills at any age.

For testing whether someone lacks the theory of mind, the Sally-Anne test is performed. The child sees the following story: Sally and Anne are playing. Sally puts her ball into a basket and leaves the room. While Sally is gone, Anne moves the ball from the basket to the box. Now Sally returns. The question is: where will Sally look for her ball? The test is passed if the child correctly assumes that Sally will look in the basket. The test is failed if the child thinks that Sally will look in the box. Children younger than four and older children with autism will generally say that Sally will look in the box.

We will look at Autism Spectrum disorder in more detail in the next section, middle and late childhood.

Language Development

The development of symbolic representation during the second year of life leads to an explosion of language growth during toddlerhood and early childhood.

Vocabulary growth. Between the ages of two to six, a child’s vocabulary expands from about 200 words to over 10,000 words. This “vocabulary spurt” typically involves 10-20 new words per week and is accomplished through a process called fast-mapping. Words are easily learned by making connections between new words and concepts already known. The parts of speech that are learned depend on the language and what is emphasized. Children speaking verb-friendly languages, such as Chinese and Japanese, learn verbs more readily, while those speaking English tend to learn nouns more readily. at the same time, children learning less verb-friendly languages, such as English, seem to need assistance in grammar to master the use of verbs (Imai et al., 2008).

Literal meanings. Children can repeat words and phrases after having heard them only once or twice, but they do not always understand the meaning of the words or phrases. This is especially true of expressions or figures of speech which are taken literally. For example, a classroom full of preschoolers hears the teacher say, “Wow! That was a piece of cake!” The children may begin asking, “Cake? Where is my cake? I want cake!” Or when a young child falls down and scrapes her knee, and she hears a parent say, “Oh, your poor knee,” as they put on a band-aid, the parent should not be surprised if, when the child falls down and scapes an elbow, she shows it to the parent and says– “Oh, man, I got another knee.”

Overregularization. Children learn rules of grammar as they learn language but may apply these rules inappropriately at first. For instance, a child learns to add “ed” to the end of a word to indicate past tense. Then, form a sentence such as “I went there. I doed that.” This is typical at ages two and three. Even without any correction, those mistakes will soon disappear, and they will learn new words, such as “went” and “did,” to be used in those situations.

The impact of training. Remember Vygotsky and the Zone of Proximal Development? Children can be assisted in learning language by others who listen attentively, model more accurate pronunciations, and encourage elaboration. The child exclaims, “I’m goed there!” and the adult responds, “You went there? Where did you go?” No corrections are needed. Children may be ripe for language, as Chomsky suggests, but active participation in helping them learn is important for language development as well. The process of scaffolding is one in which the guide provides needed assistance to the child as a new skill is learned.

Private speech. Do you ever talk to yourself? Why? Chances are, this occurs when you are struggling with a problem, trying to remember something, or feel very emotional about a situation. Children talk to themselves too. Piaget interpreted this as egocentric speech or a practice engaged in because of a child’s inability to see things from other points of view. Vygotsky, however, believed that children talk to themselves in order to solve problems or clarify thoughts. As children learn to think in words, they do so aloud before eventually closing their lips and engaging in private speech or inner speech. Thinking out loud eventually becomes thought accompanied by internal speech, and talking to oneself becomes a practice only engaged in when we are trying to learn something or remember something, etc. This inner speech is not as elaborate as the speech we use when communicating with others (Vygotsky, 1962).

Bilingualism

Although monolingual speakers often do not realize it, the majority of children around the world are bilingual, meaning that they understand and use two languages (Meyers-Sutton, 2005). Even in the United States, which is a relatively monolingual society, more than 60 million people (21%) speak a language other than English at home (Camarota & Zeigler, 2014; Ryan, 2013). Children who are dual language learners are one of the fastest-growing populations in the United States (Hammer et al., 2014). They make up nearly 30% of children enrolled in early childhood programs like Head Start. By the time they enter school, they are very heterogeneous in their language and literacy skills, with some children showing delays in proficiency in either one or both languages (Hammer et al., 2014). Hoff (2018) reports language competency is dependent on the quantity, quality, and opportunity to use a language. Dual language learners may hear the same number of words and phrases (quantity) overall, as do monolingual children, but it is split between two languages (Hoff, 2018). Thus, in any single language, they may be exposed to fewer words. They will show higher expressive and receptive skills in the language they come to hear the most.

In addition, the quality of the languages spoken to the child may differ in bilingual versus monolingual families. Place and Hoff (2016) found that for many immigrant children in the United States, most of the English heard was spoken by a non-native speaker of the language. Finally, many children in bilingual households will sometimes avoid using the family’s heritage language in favor of the majority language (DeHouwer, 2007, Hoff, 2018). A common pattern in Spanish-English homes is for the parents to speak to the child in Spanish but for the child to respond in English. As a result, children may show little difference in receptive skills between English and Spanish but better expressive skills in English (Hoff, 2018).

There are several studies that have documented the advantages of learning more than one language in childhood for cognitive executive function skills. Bilingual children consistently outperform monolinguals on measures of inhibitory control, such as ignoring irrelevant information (Bialystok, Martin & Viswanathan, 2005). Studies also reveal an advantage for bilingual children in measures of verbal working memory (Kaushanskaya, Gross, & Buac, 2014; Yoo & Kaushanskaya, 2012) and non-verbal working memory (Bialystok, 2011). However, it has been reported that among lower SES populations the working memory advantage is not always found (Bonifacci, Giombini, Beloocchi, & Conteno, 2011).

There is also considerable research to show that being bilingual, either as a child or an adult, leads to greater efficiency in the word-learning process. Monolingual children are strongly influenced by the mutual-exclusivity bias, the assumption that an object has only a single name (Kaushanskaya, Gross, & Buac, 2014). For example, a child who has previously learned the word car may be confused when this object is referred to as an automobile or sedan. Research shows that monolingual children find it easier to learn the name of a new object than acquiring a new name for a previously labelled object. In contrast, bilingual children and adults show little difficulty with either task (Kaushanskaya & Marian, 2009). This finding may be explained by the experience bilinguals have in translating between languages when referring to familiar objects.

Educational programs should take advantage of the preschool years as a time when children are developmentally primed to learn more than one language. The practice in the US of waiting until middle or high school to learn a second language flies in the face of the natural developmental progression of language learning. Systematic instruction, practice, reading, and writing in multiple languages would allow young children to become bilingual and bi-literate during a developmental period when that is relatively easy. That is why many school districts offer immersion programs in multiple languages starting in preschool or Kindergarten. School districts that serve many children who speak languages other than English can take advantage of their skills and support bilingualism in all their pupils.

Early Childhood Education

Providing universal preschool has become an important lobbying point for federal, state, and local leaders throughout our country. In his 2013 State of the Union address, President Obama called upon Congress to provide high-quality preschool for all children. He continued to support universal preschool in his legislative agenda, and in December 2014, the President convened state and local policymakers for the White House Summit on Early Education (White House Press Secretary, 2014). However, universal preschool covering all four-year-olds in the country would require significant funding. Further, how effective preschools are in preparing children for elementary school and what constitutes high-quality preschool has been debated.

To set criteria for designation as a high-quality preschool, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) identifies 10 standards (NAEYC, 2016). These include:

- Positive and caring relationships among all children and adults are promoted.

- The curriculum supports learning and development in social, emotional, physical, language, and cognitive areas.

- Teaching approaches are developmentally, culturally, and linguistically attuned.

- Children’s progress is assessed to provide information on their learning and development.

- Children’s health and nutrition are promoted while they are protected from illness and injury.

- Teachers possess the educational qualifications, knowledge, and commitment to promote children’s learning.

- Collaborative relationships with families are established and maintained.

- Relationships with agencies and institutions in the children’s communities are established to support the program’s goals.

- Indoor and outdoor physical environments are safe and well-maintained.

- Leadership and management personnel are well qualified, effective, and maintain licensure status with the applicable state agency.

Parents should review preschool programs using criteria such as those set by NAEYC as a guide and template for asking questions that will assist them in choosing the best program for their child.

Selecting the right preschool is also difficult because there are so many types of preschools available. Zachry (2013) identified Montessori, Waldorf, Reggio Emilia, High Scope, Creative Curriculum, and Bank Street as types of early childhood education programs that focus on children learning through discovery, which is considered child-centered or developmental programs. Teachers act as facilitators of children’s learning and development and create activities based on the child’s developmental level. In line with Piaget’s view, children are seen as active explorers in creating their own knowledge. In line with Vygotsky’s view, children are encouraged to play with other children.

In contrast, teacher-directed programs focus more on building academic skills. Teachers introduce new concepts that will prepare children for grade school. For example, they may identify letters, numbers, colors, and shapes. In line with behavioral theories of learning, this approach incorporates repetition, direct instruction, drills, and breaking down tasks in small steps (Parker & Neuharth-Pritchett, 2006). This approach is often driven by accountability demands by local and federal governments.

Most developmentalists favor a child-centered approach in line with the constructivist views of how children learn espoused by Piaget and Vygotsky (Parker & Neuharth-Pritchett, 2006). The NAEYC recognizes that early childhood education does not have to be an either/or proposition, and children can benefit from incorporating elements from each type of program.

Head Start. For children who live in poverty, Head Start has been providing preschool education since 1965, when it was begun by President Lyndon Johnson as part of his war on poverty. It currently serves nearly one million children and annually costs approximately 7.5 billion dollars (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2015). However, concerns about the effectiveness of Head Start have been ongoing since the program began. Armor (2015) reviewed existing research on Head Start and found there were no lasting gains, and the average child in Head Start had not learned more than children who did not receive preschool education. One study showed that 3-and 4-year-old children in Head Start received “potentially positive effects” on general reading achievement, but no noticeable effects on math achievement and social-emotional development (Barshay, 2015).

Nonexperimental designs are a significant problem in determining the effectiveness of Head Start programs because a control group is needed to show group differences that would demonstrate educational benefits. Because of ethical reasons, low-income children are usually provided with some type of preschool programming in an alternative setting. Additionally, Head Start programs are different depending on the location, and these differences include the length of the day or qualification of the teachers. Lastly, testing young children is difficult and strongly dependent on their language skills and comfort level with an evaluator (Barshay, 2015).

Despite the challenges in researching the effectiveness of Head Start, the social and economic benefits of investing in universal preschool cannot be overstated. This is especially true for preschool programs that serve disadvantaged children and communities. Researchers and economists have estimated that investing in the cost of Head Start for a single child—about $17,000—can yield a return to society of between $300,000 and $500,000 over that child’s lifetime (Heckman et al., 2010). This substantial economic return (potentially saving our society billions of dollars in the long run) comes in the form of lower high school dropout rates, lower unemployment rates, and lower rates of incarceration—all of which have been documented for individuals who had academic and social supports during early childhood (Heckman et al., 2010). Similar to the concept of preventative healthcare, the benefits of investing in early education for children in poor or underserved communities today will add up over time and will yield greater societal benefits than we would expect from programs that implement interventions after problems emerge (for example, remedial schooling, job re-training, or substance abuse rehabilitation; Heckman, 2006).

Link to Learning

Explore how teacher-directed and child-centered approaches can be combined in an early childhood classroom.

Masterson, M. L. (2021). Transforming teaching: Creating lesson plans for child-centered learning in preschool. National Association for the Education of Young Children, pp. 34–35.

Key Terms

Conservation problems: Problems pioneered by Piaget in which the physical transformation of an object or set of objects changes a perceptually salient dimension but not the quantity that is being asked about.

False-belief test: An experimental procedure that assesses whether a perceiver recognizes that another person has a false belief—a belief that contradicts reality.

Object permanence task: The Piagetian task in which infants below about 9 months of age fail to search for an object that is removed from their sight and, if not allowed to search immediately for the object, act as if they do not know that it continues to exist.

Scaffolding: a process in which adults or capable peers model or demonstrate how to solve a problem, and then step back, offering support as needed.

Sociocultural Theory: Vygotsky’s theory that emphasizes how cognitive development proceeds as a result of social interactions between members of a culture, and relies on cultural tools like language.

Theory of mind: The human capacity to understand minds, a capacity that is made up of a collection of concepts (e.g., agent, intentionality) and processes (e.g., goal detection, imitation, empathy, perspective taking).

Zone of Proximal Development: what a learner can do with help from more competent others; sits in the gap between what a learner can do alone without help, and what the learner cannot yet do.

Supplemental Materials

This study explores maternal involvement in the preschool years for Black families across three generations.

This article compares Piaget and Vygotsky’s perspectives on learning and development in a deep dive on constructivism.

Attributions

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-V). Washington, DC: Author.

Armor, D. J. (2015). Head Start or False Start. USA Today Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.questia.com/magazine/1G1-429736352/head-start-or-false-start

Autism Genome Project Consortium. (2007). Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nature Genetics, 39, 319–328.

Barshay, J. (2015). Report: Scant scientific evidence for Head Start programs’ effectiveness. U.S. News and World Report. Retrieved from http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/ 2015/08/03/report-scant-scientific-evidence-for-head-start-programs-effectiveness

Berk, L. (2007). Development through the life span (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Berwid, O., Curko-Kera, E. A., Marks, D. J., & Halperin, J. M. (2005). Sustained attention and response inhibition in young children at risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(11), 1219-1229.

Bialystok, E. (2011). Coordination of executive functions in monolingual and bilingual children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 110, 461–468.

Bialystok, E., Martin, M.M., & Viswanathan, M. (2005). Bilingualism across the lifespan: The rise and fall of inhibitory control. International Journal of Bilingualism, 9, 103–119.

Birch, S., & Bloom, P. (2003). Children are cursed: An asymmetric bias in mental-state attribution. Psychological Science, 14(3), 283-286.

Bonifacci, P., Giombini, L., Beloocchi, S., & Conteno, S. (2011). Speed of processing, anticipation, inhibition, and working memory in bilinguals. Developmental Science, 14, 256–269.

Camarota, S. A., & Zeigler, K. (2015). One in five U. S. residents speaks foreign language at home. Retrieved from https://cis.org/sites/default/files/camarota-language-15.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders, autism, and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries, 61(3), 1–19. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6103.pdf

Crain, W. (2005). Theories of development concepts and applications (5th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson.

DeStefano, F., Price, C. S., & Weintraub, E. S. (2013). Increasing exposures to antibody-stimulating proteins and polysaccharides in vaccines is not associated with risk of autism. The Journal of Pediatrics, 163, 561–567

De Houwer, A. (2007). Parental language input patterns and children’s bilingual use. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28, 411–422.

Dyer, S., & Moneta, G. B. (2006). Frequency of parallel, associative, and cooperative play in British children of different socio-economic status. Social Behavior and Personality, 34(5), 587-592.

Epley, N., Morewedge, C. K., & Keysar, B. (2004). Perspective taking in children and adults: Equivalent egocentrism but differential correction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 760–768.

Frank, G., Plunkett, S. W., & Otten, M. P. (2010). Perceived parenting, self-esteem, and general self-efficacy of Iranian American adolescents. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 19, 738-746.

Gomes, G. Sussman, E., Ritter, W., Kurtzberg, D., Vaughan, H. D. Jr., & Cowen, N. (1999). Electrophysiological evidence of development changes in the duration of auditory sensory memory. Developmental Psychology, 35, 294-302.

Gopnik, A., & Wellman, H.M. (2012). Reconstructing constructivism: Causal models, Bayesian learning mechanisms, and the theory. Psychological Bulletin, 138(6), 1085-1108.

Guy, J., Rogers, M., & Cornish, K. (2013). Age-related changes in visual and auditory sustained attention in preschool-aged children. Child Neuropsychology, 19(6), 601–614. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2012.710321

Hammer C. S., Hoff, E., Uchikosh1, Y., Gillanders, C., Castro, D., & Sandilos, L. E. (2014). The language literacy development of young dual language learners: A critical review. Early Child Research Quarterly, 29(4), 715-733.

Heckman, J. J., Moon, S. H., Pinto, R., Savelyev, P. A., & Yavitz, A. (2010). The rate of return to the HighScope Perry Preschool Program. Journal of Public Economics, 94(1-2), 114-128.

Heckman, J. J. (2006). Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science, 312(5782), 1900-1902.

Herrmann, E., & Tomasello, M. (2015). Focusing and shifting attention in human children (homo sapiens) and chimpanzees (pan troglodytes). Journal of Comparative Psychology, 129(3), 268–274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0039384

Herrmann, E., Misch, A., Hernandez-Lloreda, V., & Tomasello, M. (2015). Uniquely human self-control begins at school age. Developmental Science, 18(6), 979-993. doi:10.1111/desc.12272.

Hoff, E. (2018). Bilingual development in children of immigrant families. Child Development Perspectives, 12(2), 80-86.

Hughes, V. (2007). Mercury rising. Nature Medicine, 13, 896-897.

Imai, M., Li, L., Haryu, E., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., & Shigematsu, J. (2008). Novel noun and verb learning in Chinese, English, and Japanese children: Universality and language-specificity in novel noun and verb learning. Child Development, 79, 979-1000.

John-Steiner, V., & Mahn, H. (1996). Sociocultural approaches to learning and development: A Vygotskian framework. Educational psychologist, 31(3-4), 191-206.

Jones, J. M. (2013). In U.S., 40% Get Less than Recommended Amount of Sleep. Gallup. http://www.gallup.com/poll/166553/less-recommended-amount sleep.aspx?g_source=sleep%202013&g_medium=search&g_campaign=tiles

Kaushanskaya, M., Gross, M., & Buac, M. (2014). Effects of classroom bilingualism on task-shifting, verbal memory, and word learning in children. Developmental Science, 17(4), 564-583.

Kaushanskaya, M., & Marian, V. (2009). Bilingualism Reduces Native-Language Interference During Novel-Word Learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35(3), 829–835. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015275

Kozulin, A. (1990). The concept of regression and Vygotskian developmental theory. Developmental review, 10(2), 218-238.

Malle, B. (2024). Theory of mind. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/a8wpytg3

Matusov, E. (2015). Comprehension: A dialogic authorial approach. Culture & Psychology, 21(3), 392-416.

McAlister, A. R., & Peterson, C. C. (2007). A longitudinal study of siblings and theory of mind development. Cognitive Development, 22, 258-270.

Meek, S. E., Lemery-Chalfant, K., Jahromi, L. D., & Valiente, C. (2013). A review of gene-environment correlations and their implications for autism: A conceptual model. Psychological Review, 120, 497–521

Meyers-Sutton, C. (2005). Multiple voices: An introduction to bilingualism. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Miller, R. (2011). Vygotsky in perspective. Cambridge University Press.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2016). The 10 NAEYC program standards. Retrieved from http://families.naeyc.org/accredited-article/10-naeyc-program-standards

Perner, J., Ruffman, T., & Leekam, S. R. (1994). Theory of mind is contagious: You catch from your sibs. Child Development, 65, 1228-1238.

Place, S., & Hoff, E. (2016). Effects and non-effects of input in bilingual environments on dual language skills in 2 1/2-year-olds. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 19, 1023–1041.

Price-Williams, D.R., Gordon, W., & Ramirez, M. (1969). Skill and conservation: A study of pottery making children. Developmental Psychology, 1, 769.

Posner, M.I., & Rothbart, M.K. (2007). Research on attention networks as a model for the integration of psychological science. Annual Review in Psychology, 58, 1–23

Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. Oxford University Press.

Ryan, C. (2013). Language use in the United States: 2011. Retrieved from https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2013/acs/acs-22/acs-22.pdf

Schneider, W., Kron-Sperl, V., & Hünnerkopf, M. (2009). The development of young children’s memory strategies: Evidence from the Würzburg Longitudinal Memory Study. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 6, 70-99.

Scott, S., & Palincsar, A. (2013). Sociocultural theory. Education. com, 1-4.

Shahaeian, A., Peterson, C. C., Slaughter, V., & Wellman, H. M. (2011). Culture and the sequence of steps in theory of mind development. Developmental Psychology, 47(5), 1239-1247.

Thomas, R. M. (1979). Comparing theories of child development. Santa Barbara, CA: Wadsworth. Berk, L. E. (2007). Development through the life span (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2015). Head Start program facts fiscal year 2013. Retrieved from http://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/data/factsheets/docs/hs-program-fact-sheet-2013.pdf

Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Socio-cultural theory. Mind in society.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition, 13, 103–128.

Wellman, H.M., Cross, D., & Watson, J. (2001). Meta-analysis of theory of mind development: The truth about false belief. Child Development, 72(3), 655-684.

Wellman, H. M., Fang, F., Liu, D., Zhu, L, & Liu, L. (2006). Scaling theory of mind understandings in Chinese children. Psychological Science, 17, 1075-1081.

White House Press Secretary. (2014). Fact Sheet: Invest in US: The White House Summit on Early Childhood Education. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/12/10/fact-sheet-invest-us-white-house-summit-early-childhood-education

Yoo, J., & Kaushanskaya, M. (2012). Phonological memory in bilinguals and monolinguals. Memory & Cognition, 40, 1314–1330.

Zachry, A. (2013). 6 Types of Preschool Programs. Retrieved from http://www.parents.com/toddlers-preschoolers/starting -preschool/preparing/types-of-preschool-programs/