Section 10: Middle Adulthood

10.2 Cognitive Development in Middle Adulthood

While we sometimes associate aging with cognitive decline (often due to the way it is portrayed in the media), aging does not necessarily mean a decrease in cognitive function. In fact, tacit knowledge, verbal memory, vocabulary, inductive reasoning, and other types of practical thought skills increase with age. We’ll learn about these advances as well as some neurological changes that happen in middle adulthood in the section that follows.

Learning Objectives

- Describe cognitive and neurological changes during middle adulthood

- Outline cognitive gains/deficits typically associated with middle adulthood

- Explain changes in fluid and crystallized intelligence during adulthood

- Analyze emotional and social development in middle adulthood

- Explain the sources of stress confronting adults in midlife and the strategies to cope

Cognition in Middle Adulthood

One of the most influential perspectives on cognition during middle adulthood has been that of the Seattle Longitudinal Study (SLS) of adult cognition, which began in 1956. It’s one of the most famous sequential designs that compared cohorts and followed them over time. Schaie & Willis (2010) summarized the general findings from this series of studies as follows: “We have generally shown that reliably replicable average age decrements in psychometric abilities do not occur prior to age 60, but that such reliable decrement can be found for all abilities by 74 years of age.” In short, decreases in cognitive abilities begin in the sixth decade and gain increasing significance from that point on. However, Singh-Maoux et al. (2012) argue for small but significant cognitive declines beginning as early as age 45. There is some evidence that adults should be as aggressive in maintaining their cognitive health as they are in their physical health during this time, as the two are intimately related.

The second source of longitudinal research data on this part of the lifespan has been The Midlife in the United States Studies (MIDUS), which began in 1994. The MIDUS data supports the view that this period of life is something of a trade-off, with some cognitive and physical decreases of varying degrees. The cognitive mechanics of processing speed, often referred to as fluid intelligence, physiological lung capacity, and muscle mass, are in relative decline. However, knowledge, experience, and the increased ability to regulate our emotions can compensate for these losses. Continuing cognitive focus and exercise can also reduce the extent and effects of cognitive decline.

Control Beliefs

Central to all of this is personal control beliefs, which have a long history in psychology. Beginning with the work of Julian Rotter (1954), a fundamental distinction is drawn between those who believe that they are the fundamental agents of what happens in their lives and those who believe that they are largely at the mercy of external circumstances. Those who believe that life outcomes are dependent on what they say and do are said to have a strong internal locus of control. Those who believe that they have little control over their life outcomes are said to have an external locus of control.

Empirical research has shown that those with an internal locus of control enjoy better results in psychological tests across the board: behavioral, motivational, and cognitive. It is reported that this belief in control declines with age, but again, there is a great deal of individual variation. This raises another issue: directional causality. Does my belief in my ability to retain my intellectual skills and abilities at this time of life ensure better performance on a cognitive test compared to those who believe in their inexorable decline? Or does the fact that I enjoy that intellectual competence or facility instill or reinforce that belief in control and controllable outcomes? It is not clear which factor is influencing the other. The exact nature of the connection between control beliefs and cognitive performance remains unclear.

Brain science is developing exponentially and will unquestionably deliver new insights on a whole range of issues related to cognition in midlife. One of them will surely be on the brain’s capacity to renew, or at least replenish itself, at this time of life. The capacity to renew is called neurogenesis; the capacity to replenish what is there is called neuroplasticity. At this stage, it is impossible to ascertain exactly what effect future pharmacological interventions may have on the possible cognitive decline at this and later stages of life.

Try It

Cognitive Aging

Researchers have identified areas of loss and gain in cognition in older age. Cognitive ability and intelligence are often measured using standardized tests and validated measures. The psychometric approach has identified two categories of intelligence that show different rates of change across the life span (Schaie & Willis, 1996). Fluid and crystallized intelligence were first identified by Cattell in 1971. Fluid intelligence refers to information processing abilities, such as logical reasoning, remembering lists, spatial ability, and reaction time. Crystallized intelligence encompasses abilities that draw upon experience and knowledge. Measures of crystallized intelligence include vocabulary tests, solving number problems, and understanding texts. There is a general acceptance that fluid intelligence decreases continually from the 20s, but that crystallized intelligence continues to accumulate. One might expect to complete the NY Times crossword more quickly at 48 than at 22, but the capacity to deal with novel information declines.

With age, systematic declines are observed in cognitive tasks requiring self-initiated, effortful processing without the aid of supportive memory cues (Park, 2000). Older adults tend to perform poorer than young adults on memory tasks that involve recall of information, where individuals must retrieve the information they learned previously without the help of a list of possible choices. For example, older adults may have more difficulty recalling facts such as names or contextual details about where or when something happened (Craik, 2000). What might explain these deficits as we age?

As we age, working memory, or our ability to simultaneously store and use information, becomes less efficient (Craik & Bialystok, 2006). The ability to process information quickly also decreases with age. This slowing of processing speed may explain age differences in many different cognitive tasks (Salthouse, 2004). Some researchers have argued that inhibitory functioning, or the ability to focus on certain information while suppressing attention to less pertinent information, declines with age and may explain age differences in performance on cognitive tasks (Hasher & Zacks, 1988).

Fewer age differences are observed when memory cues are available, such as for recognition-style memory tasks or when individuals can draw upon acquired knowledge or experience. For example, older adults often perform as well, if not better, than young adults on tests of word knowledge or vocabulary. With age often comes expertise, and research has pointed to areas where aging experts perform as well or better than younger individuals. For example, older typists were found to compensate for age-related declines in speed by looking farther ahead at the printed text (Salthouse, 1984). Compared to younger players, older chess experts are able to focus on a smaller set of possible moves, leading to greater cognitive efficiency (Charness, 1981). Accrued knowledge of everyday tasks, such as grocery prices, can help older adults make better decisions than young adults (Tentori et al., 2001).

We began with Schaie and Willis (2010) observing that no discernible general cognitive decline could be observed before 60, but other studies contradict this notion. How do we explain this contradiction? In a thought-provoking article, Ramscar et al. (2014) argued that an emphasis on information processing speed ignored the effect of the process of learning/experience itself; that is, such tests ignore the fact that more information to process leads to slower processing in both computers and humans. We have more complex cognitive systems at 55 than at 25.

This video highlights some of the cognitive changes during adulthood as well as the characteristics that either decline, improve, or remain stable.

Try It

Performance in Middle Adulthood

Research on interpersonal problem-solving suggests that older adults use more effective strategies than younger adults to navigate through social and emotional problems (Blanchard-Fields, 2007). In the context of work, researchers rarely find that older individuals perform less well on the job (Park & Gutchess, 2000). Similar to everyday problem solving, older workers may develop more efficient strategies and rely on expertise to compensate for cognitive decline.

Given their nature, empirical studies of cognitive aging are often difficult and quite technical. Similarly, experiments focused on one kind of task may tell you very little about general capacities. Memory and attention as psychological constructs are now divided into very specific subsets, which can be confusing and difficult to compare.

However, one study does show with relative clarity the issues involved. In the USA, The Federal Aviation Authority insists that all air traffic controllers retire at 56 and that they cannot begin until age 31 unless they have previous military experience. However, in Canada, controllers are allowed to work until age 65 and are allowed to train at a much earlier age. Nunes and Kramer (2009) studied four groups: a younger group of controllers (20-27), an older group of controllers aged 53 to 64, and two other groups of the same age who were not air traffic controllers. On simple cognitive tasks not related to their occupational lives as controllers, older controllers were slower than their younger peers. However, when it came to job-related tasks, their results were largely identical. This was not true of the older group of non-controllers, who had significant deficits in comparison. Specific knowledge or expertise in a domain acquired over time (crystallized intelligence) can offset a decline in fluid intelligence.

Intelligence in Middle Adulthood

The brain at midlife has been shown to not only maintain many of the abilities of young adults, but also gain new ones. Some individuals in middle age actually have improved cognitive functioning (Phillips, 2011). The brain continues to demonstrate plasticity and rewires itself in middle age based on experiences. Research has demonstrated that older adults use more of their brains than younger adults. In fact, older adults who perform the best on tasks are more likely to demonstrate bi-lateralization than those who perform worst. Additionally, the amount of white matter in the brain, which is responsible for forming connections among neurons, increases into the 50s before it declines.

Emotionally, the middle-aged brain is calmer, less neurotic, more capable of managing emotions, and better able to negotiate social situations (Phillips, 2011). Older adults tend to focus more on positive information and less on negative information than younger adults. In fact, they also remember positive images better than those younger. Additionally, the older adult’s amygdala responds less to negative stimuli. Lastly, adults in middle adulthood make better financial decisions, a capacity that seems to peak at age 53 and show better economic understanding. Although greater cognitive variability occurs among middle-aged adults when compared to those both younger and older, those in midlife who experience cognitive improvements tend to be more physically, cognitively, and socially active.

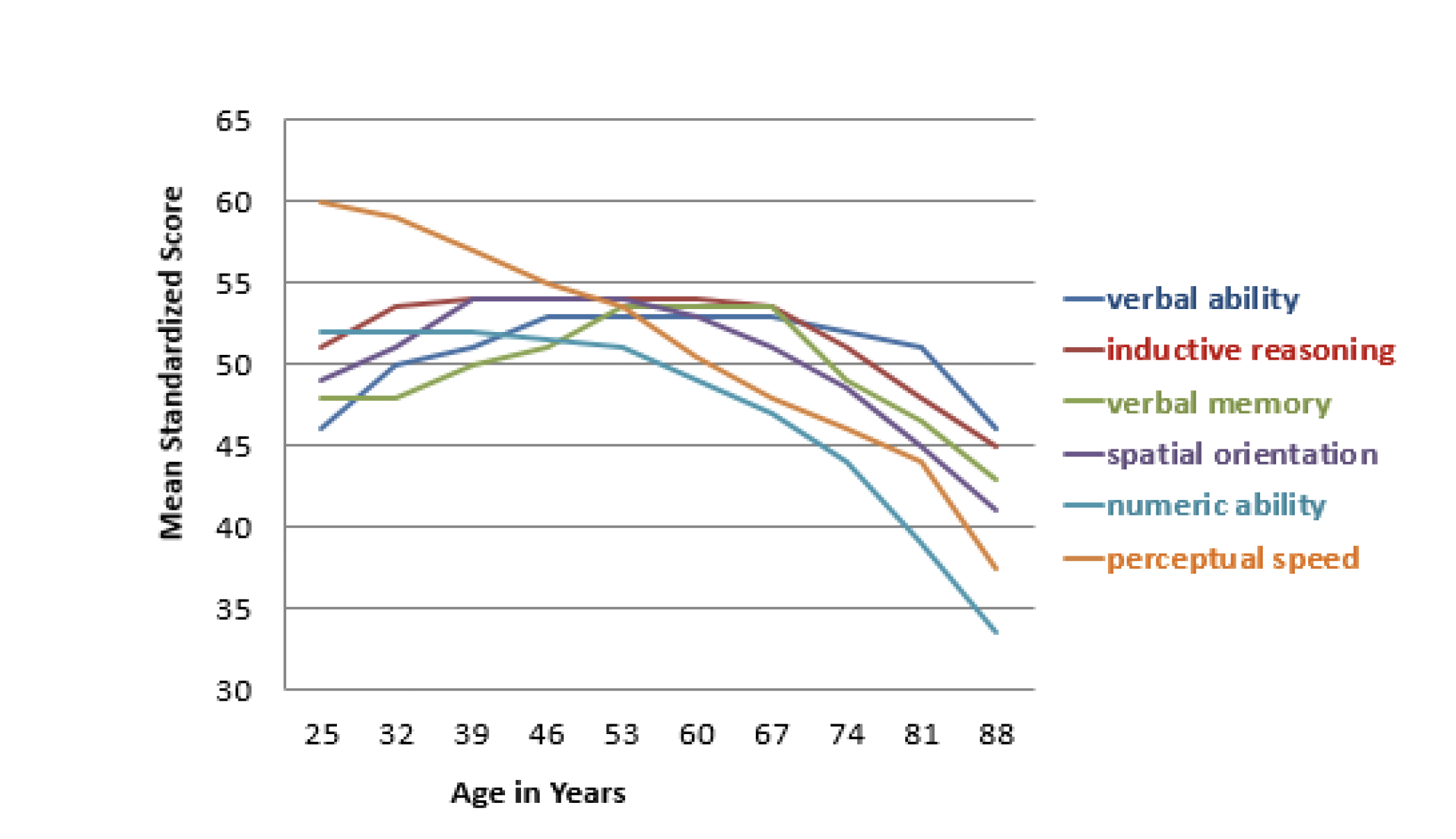

Crystalized versus Fluid Intelligence. Intelligence is influenced by heredity, culture, social contexts, personal choices, and certainly age. One distinction in specific intelligence noted in adulthood is between fluid intelligence, which refers to the capacity to learn new ways of solving problems and performing activities quickly and abstractly, and crystallized intelligence, which refers to the accumulated knowledge of the world we have acquired throughout our lives (Salthouse, 2004). These intelligence are distinct, and crystallized intelligence increases with age, while fluid intelligence tends to decrease with age (Figure 4) (Horn et al., 1981; Salthouse, T. A. (2004).

Fluid intelligence sometimes called the mechanics of intelligence, tends to rely on the perceptual speed of processing, and perceptual speed is one of the primary capacities that shows age-graded declines starting in early adulthood, as seen not only in cognitive tasks but also in athletic performance and other tasks that require speed. In contrast, research demonstrates that crystallized intelligence, also called the pragmatics of intelligence, continues to grow during adulthood as older adults acquire additional semantic knowledge, vocabulary, and language. As a result, adults generally outperform younger people on tasks where this information is useful, such as measures of history, geography, and even crossword puzzles (Salthouse, 2004). It is this superior knowledge, combined with a slower and more complete processing style, along with a more sophisticated understanding of the workings of the world around them, that gives older adults the advantage of “wisdom” over the advantages of fluid intelligence, which favor the young (Baltes, Staudinger, & Lindenberger, 1999; Scheibe, Kunzmann, & Baltes, 2009).

The differential changes in crystallized versus fluid intelligence help explain why older adults do not necessarily show poorer performance on tasks that also require experience (i.e., crystallized intelligence), although they show poorer memory overall. A young chess player may think more quickly, for instance, but a more experienced chess player has more knowledge to draw on.

Seattle Longitudinal Study. The Seattle Longitudinal Study has tracked the cognitive abilities of adults since 1956. Every seven years the current participants are evaluated, and new individuals are also added. Approximately 6000 people have participated thus far, and 26 people from the original group are still in the study today. Current results demonstrate that middle-aged adults perform better on four out of six cognitive tasks than those same individuals did when they were young adults. Verbal memory, spatial skills, inductive reasoning (generalizing from particular examples), and vocabulary increase with age until one’s 70s (Schaie, 2005; Willis & Shaie, 1999). In contrast, perceptual speed declines starting in early adulthood, and numerical computation shows declines starting in middle and late adulthood (see Figure 5).

Cognitive skills in the aging brain have been extensively studied in pilots. Similar to the Seattle Longitudinal Study results, older pilots show declines in processing speed and memory capacity, but their overall performance seems to remain intact. According to Phillips (2011), researchers tested pilots aged 40 to 69 as they performed on flight simulators. Older pilots took longer to learn to use the simulators but subsequently performed better than younger pilots at avoiding collisions.

Tacit knowledge is knowledge that is pragmatic or practical and learned through experience rather than explicitly taught, and it also increases with age (Hedlund, Antonakis, & Sternberg, 2002). Tacit knowledge might be thought of as “know-how” or “professional instinct.” It is referred to as tacit because it cannot be codified or written down. It does not involve academic knowledge; rather, it involves being able to use skills and to problem-solve in practical ways. Tacit knowledge can be seen clearly in the workplace and underlies the steady improvements in job performance documented across age and experience, as seen, for example, in the performance of both white and blue-collar workers, such as carpenters, chefs, and hairdressers.

Flow is the mental state of being completely present and fully absorbed in a task (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). When in a state of flow, the individual is able to block outside distractions, and the mind is fully open to producing. Additionally, the person is achieving great joy or intellectual satisfaction from the activity and accomplishing a goal. Further, when in a state of flow, the individual is not concerned with extrinsic rewards. Csikszentmihalyi (1996) used his theory of flow to research how some people exhibit high levels of creativity, as he believed that a state of flow is an important factor in creativity (Kaufman & Gregoire, 2016). Other characteristics of creative people identified by Csikszentmihalyi (1996) include curiosity and drive, a value for intellectual endeavors, and an ability to lose our sense of self and feel a part of something greater. In addition, he believed that the tortured creative person was a myth and that creative people were very happy with their lives. According to Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi (2002), people describe flow as the height of enjoyment. The more they experience it, the more they judge their lives to be gratifying. The qualities that allow for flow are well-developed in middle adulthood.

Back to school!

Middle Adults Returning to College. Midlife adults in the United States often find themselves in university classrooms. In fact, the rate of enrollment for older Americans entering college, often part-time or in the evenings, is rising faster than that of traditionally aged students. Students over age 35 accounted for 17% of all college and graduate students in 2009 and are expected to comprise 19% of that total by 2020 (Holland, 2014). In some cases, older students are developing skills and expertise in order to launch a second career, or to take their career in a new direction. Whether they enroll in school to sharpen particular skills, to retool and reenter the workplace, or to pursue interests that have previously been neglected, older students tend to approach the learning process differently than younger college students (Knowles, Holton, & Swanson, 1998).

The mechanics of cognition, such as working memory and speed of processing, gradually decline with age. However, they can be easily compensated for through the use of higher-order cognitive skills, such as forming strategies to enhance memory or summarizing and comparing ideas rather than relying on rote memorization (Lachman, 2004). Although older students may take a bit longer to learn the material, they are less likely to forget it as quickly. Adult learners tend to look for relevance and meaning when learning information. Older adults have the hardest time learning material that is meaningless or unfamiliar. They are more likely to ask themselves, “Why is this important?” when being introduced to information or when trying to memorize concepts or facts.

Older adults are more task-oriented learners and want to organize their activity around problem-solving or making contributions to real-world issues. Rubin et al. (2018) surveyed university students aged 17-70 regarding their satisfaction and approach to learning in college. Results indicated that older students were more independent, inquisitive, and intrinsically motivated compared to younger students. Additionally, older women processed information at a deeper learning level and expressed more satisfaction with their education. Just as at younger ages, during middle adulthood, more women than men are likely to attend and graduate from college.

To address the educational needs of those over 50, The American Association of Community Colleges (2016) developed the Plus 50 Initiative, which assists community colleges in creating or expanding programs that focus on workforce training and new careers for the plus-50 population. Since 2008 the program has provided grants for programs in 138 community colleges affecting over 37, 000 students. The participating colleges offer workforce training programs that prepare 50 plus adults for careers such as early childhood educators, certified nursing assistants, substance abuse counselors, adult basic education instructors, and human resources specialists. These training programs are especially beneficial because 80% of people over the age of 50 say they will retire later in life than their parents or continue to work in retirement, including work in a new field.

Visit PBS’ website for the story of Jules Means, who returned to higher education late in life.

Sleep

According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (Kasper, 2015), adults require at least 7 hours of sleep per night to avoid the health risks associated with chronic sleep deprivation. Less than 6 hours and more than 10 hours is also not recommended for those in middle adulthood (National Sleep Foundation, 2015). Not surprisingly, many Americans do not receive the 7-9 hours of sleep recommended. In 2013, only 59% of U.S. adults met that standard, while in 1942, 84% did (Jones, 2013). This means 41% of Americans receive less than the recommended amount of nightly sleep. Additional results included that in 1993, 67% of Americans felt they were getting enough sleep, but in 2013, only 56% felt they received as much sleep as needed. Additionally, 43% of Americans in 2013 believed they would feel better with more sleep.

Sleep problems: According to the Sleep in America poll (2015), 9% of Americans report being diagnosed with a sleep disorder, and of those, 71% have sleep apnea, and 24% suffer from insomnia. Pain is also a contributing factor in the difference between the amount of sleep Americans say they need and the amount they are getting. An average of 42 minutes of sleep debt occurs for those with chronic pain and 14 minutes for those who have suffered from acute pain in the past week. Stress and overall poor health are also key components of shorter sleep durations and worse sleep quality. Those in midlife with lower life satisfaction experienced a greater delay in the onset of sleep than those with higher life satisfaction. Delayed onset of sleep could be the result of worry and anxiety during midlife, and improvements in those areas should improve sleep. Lastly, menopause can affect a woman’s sleep duration and quality (National Sleep Foundation, 2016).

| Demographic | Sleep less than 7 hours |

| Single Mothers | 43.5% |

| Mothers with Partner | 31.2% |

| Women without Children | 29.7% |

| Single Fathers | 37.5% |

| Fathers with Partner | 34.1% |

| Men without Children | 32.3% |

Children in the home and sleep: As expected, having children at home affects the amount of sleep one receives. According to a 2016 National Center for Health Statistics analysis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016), having children decreases the amount of sleep an individual receives; however, having a partner can improve the amount of sleep for both males and females. Table 1 illustrates the percentage of individuals not receiving seven hours of sleep per night based on parental role.

Negative consequences of insufficient sleep

There are many consequences of too little sleep, and they include physical, cognitive, and emotional changes. Sleep deprivation suppresses immune responses that fight off infection and can lead to obesity, memory impairment, and hypertension (Ferrie et al., 2007; Kushida, 2005). Insufficient sleep is linked to an increased risk of colon cancer, breast cancer, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes (Pattison, 2015). A lack of sleep can increase stress as cortisol (a stress hormone) remains elevated, which keeps the body in a state of alertness and hyperarousal, which increases blood pressure. Sleep is also associated with longevity. Dew et al (2003) found that older adults who had better sleep patterns also lived longer. During deep sleep, a growth hormone is released, which stimulates protein synthesis, breaks down fat that supplies energy, and stimulates cell division. Consequently, a decrease in deep sleep contributes to less growth hormone being released and subsequent physical decline seen in aging (Pattison, 2015).

Sleep disturbances can also impair glucose functioning in middle adulthood. Caucasian, African American, and Chinese non-shift-working women aged 48–58 years who were not taking insulin-related medications participated in the Study of Women’s Health across the Nation (SWAN) Sleep Study and were subsequently examined approximately 5 years later (Taylor et al., 2016). Body mass index (BMI) and insulin resistance were measured at two-time points. Results indicated that irregular sleep schedules, including highly variable bedtimes and staying up much later than usual, are associated in midlife women with insulin resistance, which is an important indicator of metabolic health, including diabetes risk. Diabetes risk increases in midlife women, and irregular sleep schedules may be an important reason because irregular bedtime schedules expose the body to varying levels of light, which is the most important timing cue for the body’s circadian clock. By disrupting circadian timing, bedtime variability may impair glucose metabolism and energy homeostasis.

Attributions

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

References

American Association of Community Colleges. (2022). Fast Facts 2022. https://www.aacc.nche.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/AACC_2022_Fact_Sheet.pdf

Baltes, P. B., Staudinger, U. M., & Lindenberger, U. (1999). Lifespan Psychology: Theory and Application to Intellectual Functioning. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 471-507.

Blanchard-Fields, F. (2007). Everyday problem solving and emotion: An adult development perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 26–31.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). The National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/index.htm

Charness, N. (1981). Search in chess: Age and skill differences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 7, 467.

Charness, N., & Krampe, R. T. (2006). Aging and expertise. In K. Ericsson, N. Charness & P. Feltovich (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook of expertise and expert performance. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Craik, F. I. M. (2000). Age-related changes in human memory. In D. C. Park & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Cognitive Aging: A Primer (pp. 75–92). New York: Psychology Press.

Craik, F. I., & Bialystok, E. (2006). Cognition through the lifespan: mechanisms of change. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10, 131–138.

Crawford, S. & Channon, S. (2002). Dissociation between performance on abstract tests of executive function and problem solving in real life type situations in normal aging. Aging and Mental Health, 6, 12-21.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York: Harper Collins.

Dew, M. A., Hoch, C. C., Buysse, D. J., Monk, T. H., Begley, A. E., Houck, P. R.,…Reynolds, C. F., III. (2003). Healthy older adults’ sleep predicts all-cause mortality at 4 to 19 years of follow-up. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(1), 63–73.

Ferrie, J. E., Shipley, M. J., Cappuccio, F. P., Brunner, E., Miller, M. A., Kumari, M., & Marmot, M. G. (2007). A prospective study of change in sleep duration: Associations with mortality in the Whitehall II cohort. Sleep, 30(12), 1659.

Hasher, L. & Zacks, R. T. (1988). Working memory, comprehension, and aging: A review and a new view. In G.H. Bower (Ed.), The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, (Vol. 22, pp. 193–225). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Hedlund, J., Antonakis, J., & Sternberg, R. J. (2002). Tacit knowledge and practical intelligence: Understanding the lessons of experience. http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/army/ari_tacit_knowledge.pdf

Holland, K. (2014). Why America’s campuses are going gray. CNBC. http://www.cnbc.com/2014/08/28/why- americas-campuses-are-going-gray.html

Horn, J. L., Donaldson, G., & Engstrom, R. (1981). Apprehension, memory, and fluid intelligence decline in adulthood. Research on Aging, 3(1), 33-84.

Jensen, A. R., & Cattell, R. B. (1974). Abilities: Their structure, growth, and action. The American Journal of Psychology, 87(1/2), 290. https://doi.org/10.2307/1422024

Jones, J. M. (2013). In U.S., 40% Get Less than Recommended Amount of Sleep. Gallup. http://www.gallup.com/poll/166553/less-recommended- amount sleep.aspx?g_source=sleep%202013&g_medium=search&g_campaign=tiles

Kaufman, S. B., & Gregoire, C. (2016). How to cultivate creativity. Scientific American Mind, 27(1), 62-67.

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (1998). The adult learner: A neglected species. Houston: Gulf Pub., Book Division.

Kasper, T. (2015). Why you only need 7 hours of sleep. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. http://sleepeducation.org/news/2015/06/03/why-you-only-need-7-hours-of-sleep

Kushida, C. (2005). Sleep deprivation: basic science, physiology, and behavior. London, England: Informal Healthcare.

Lachman, M. E. (2004). Development in Midlife. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 305-331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141521

Lachman, M. E., Teshale, S., & Agrigoroaei, S. (2014). Midlife as a Pivotal Period in the Life Course: Balancing Growth and Decline at the Crossroads of Youth and Old Age. International journal of behavioral development, 39(1), 20-31.

National Sleep Foundation. (2015). 2015 Sleep in America™ poll finds pain a significant challenge when it comes to Americans’ sleep. National Sleep Foundation. https://sleepfoundation.org/media-center/press-release/2015-sleep- america-poll

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 89-105). New York: Oxford University Press.

National Sleep Foundation. (2015). The 2015 Sleep in America™ poll finds pain a significant challenge when it comes to Americans’ sleep. National Sleep Foundation. https://sleepfoundation.org/media-center/press-release/2015-sleep- america-poll

National Sleep Foundation. (2016). Menopause and Insomnia. National Sleep Foundation. https://sleepfoundation.org/ask-the-expert/menopause-and-insomnia

Neugarten, B. L. (1968). The awareness of middle aging. In B. L. Neugarten (Ed.), Middle age and aging (pp. 93-98). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nunes, A., & Kramer, A. F. (2009). Experience-based mitigation of age-related performance declines: evidence from air traffic control. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Applied, 15(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014947

Park, D. C. (2000). The basic mechanisms accounting for age-related decline in cognitive function. In D.C. Park & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Cognitive Aging: A Primer (pp. 3–21). New York: Psychology Press.

Park, D. C. & Gutchess, A. H. (2000). Cognitive aging and everyday life. In D.C. Park & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Cognitive Aging: A Primer (pp. 217–232). New York: Psychology Press.

Pattison, K. (2015). Sleep deficit. Experience Life. https://experiencelife.com/article/sleep-deficit/

Phillips, M. L. (2011). The mind at midlife. American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/monitor/2011/04/mind-midlife.aspx

Polanyi, M. (1967). Tacit Dimension. Doubleday Books.

Ramscar, M., Hendrix, P., Shaoul, C., Milin, P., & Baayen, H. (2014). The myth of cognitive decline: non-linear dynamics of lifelong learning. Topics in Cognitive Science, 6(1), 5–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12078

Research Network on Successful Midlife Development. (2007, February 7). Midlife Research – MIDMAC WebSite. Retrieved from http://midmac.med.harvard.edu/research.html

Rotter, J. B. (1954). Social Learning and Clinical Psychology. Prentice-Hall.

Rubin, M., Scevak, J., Southgate, E., Macqueen, S., Williams, P., & Douglas, H. (2018). Older women, deeper learning, and greater satisfaction at university: Age and gender predict university students’ learning approach and degree satisfaction. Diversity in Higher Education, 11(1), 82-96.

Salthouse, T. A. (1984). Effects of age and skill in typing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113, 345.

Salthouse, T. A. (2004). What and when of cognitive aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 140–144.

Schaie, K. W. & Willis, S. L. (1996). Psychometric intelligence and aging. In F. Blanchard-Fields & T.M. Hess (Eds.), Perspectives on Cognitive Change in Adulthood and Aging (pp. 293–322). New York: McGraw Hill.

Schaie, K. W. (2005). Developmental influences on adult intelligence the Seattle longitudinal study. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schaie, K. W., & Willis, S. L. (2010). The Seattle longitudinal study of adult cognitive development. ISSBD Bulletin, 57(1), 24–29.

Scheibe, S., Kunzmann, U. & Baltes, P. B. (2009). New territories of Positive Lifespan Development: Wisdom and Life Longings. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Singh-Manoux, A., Kivimaki, M., Glymour, M. M., Elbaz, A., Berr, C., Ebmeier, K. P., Ferrie, J. E., & Dugravot, A. (2012). Timing of onset of cognitive decline: results from Whitehall II prospective cohort study. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 344(jan04 4), d7622. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d7622

Tangri, S., Thomas, V., & Mednick, M. (2003). Prediction of satisfaction among college-educated African American women. Journal of Adult Development, 10, 113-125.

Taylor, B. J., Matthews, K. A., Hasler, B. P., Roecklein, K. A., Kline, C. E., Buysse, D. J., Kravitz, H. M., Tiani, A. G., Harlow, S. D., & Hall, M. H. (2016). Bedtime variability and metabolic health in midlife women: the SWAN sleep study. Sleep, 39(2), 457–465.

Tentori, K., Osherson, D., Hasher, L., & May, C. (2001). Wisdom and aging: Irrational preferences in college students but not older adults. Cognition, 81, B87–B96.

Willis, S. L., & Schaie, K. W. (1999). Intellectual functioning in midlife. In S. L. Willis & J. D. Reid (Eds.), Life in the Middle: Psychological and Social Development in Middle Age (pp. 233-247). San Diego: Academic.

World Health Organization. (2018). Top 10 causes of death. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/causes_death/top_10/en/