Section 11: Late Adulthood

11.2 Physical Change in Late Adulthood: Primary and Secondary Aging

What are physical changes in late adulthood?

In this section, you’ll learn more about physical changes in late adulthood. While late adulthood is generally a time of physical decline, there are no set rules on how this happens. Individuals experience both primary and secondary physical changes. Primary aging encompasses inevitable biological processes such as reduced muscle mass, bone density, and skin elasticity, along with slower metabolism and organ function. These changes are genetically programmed and occur universally. Conversely, secondary aging involves changes influenced by lifestyle, environment, and disease, such as osteoporosis, arthritis, and cardiovascular issues, which can be mitigated through healthy behaviors and medical interventions. Understanding these distinctions helps in promoting health and well-being in later life.

Learning Objectives

- Describe physical changes in late adulthood

- Describe primary aging, including vision and hearing loss

- Explain secondary aging concerns that are common in late adulthood, including illnesses and diseases

Normal Aging

The Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (BLSA, 2011) began in 1958 and has traced the aging process in 1,400 people from age 20 to 90. Researchers from the BLSA have found that the aging process varies significantly from individual to individual and from one organ system to another. Kidney function may deteriorate earlier in some individuals.

Bone strength declines more rapidly in others. Much of this is determined by genetics, lifestyle, and disease. However, some generalizations about the aging process have been found:

- Heart muscles thicken with age

- Arteries become less flexible

- Lung capacity diminishes

- Brain cells lose some functioning, but new neurons can also be produced

- Kidneys become less efficient in removing waste from the blood

- The bladder loses its ability to store urine

- Body fat stabilizes and then declines

- Muscle mass is lost without exercise

- Bone mineral is lost. Weight-bearing exercise slows this down.

Primary and Secondary Aging. Healthcare providers need to be aware of which aspects of aging are reversible and which ones are inevitable. By keeping this distinction in mind, caregivers may be more objective and accurate when diagnosing and treating older patients. And a positive attitude can go a long way toward motivating patients to stick with a health regime. Unfortunately, stereotypes can lead to misdiagnosis. For example, it is estimated that about 10 percent of older patients diagnosed with dementia are actually depressed or suffering from some other psychological illness (Berger, 2005). The failure to recognize and treat psychological problems in older patients may be one consequence of such stereotypes.

Watch this video clip from the National Institute of Health as it explains the research involved in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging. You’ll see some of the tests done on individuals, including measurements on energy expenditure, strength, proprioception, and brain imaging and scans. Watch the The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA).

Primary Aging

Senescence is biological aging associated with the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics. It is the process by which cells irreversibly stop dividing and enter a state of permanent growth arrest without undergoing cell death. This process is also referred to as primary aging and, thus, refers to the inevitable changes associated with aging (Busse, 1969). These changes include changes in the skin and hair, height and weight, hearing loss, and eye disease. However, some of these changes can be reduced by limiting exposure to the sun, eating a nutritious diet, and exercising.

Primary aging can be compensated for through exercise, corrective lenses, nutrition, and hearing aids. Just as important, by reducing stereotypes about aging, people of age can maintain self-respect, recognize their own strengths, and count on receiving the respect and social inclusion they deserve.

Body Changes. Everyone’s body shape changes naturally as they age. According to the National Library of Medicine (2014), after age 30, people tend to lose lean tissue, and some of the cells of the muscles, liver, kidney, and other organs are lost. Tissue loss reduces the amount of water in the body, and bones may lose some of their minerals and become less dense (a condition called osteopenia in the early stages and osteoporosis in the later stages). The amount of body fat goes up steadily after age 30, and older individuals may have almost one-third more fat compared to when they were younger. Fat tissue builds up toward the center of the body, including around the internal organs.

Skin, Hair, and Nails. With age, skin loses fat and becomes thinner, less elastic, and no longer looks plump and smooth. Veins and bones can be seen more easily, and scratches, cuts, and bumps can take longer to heal. Years of exposure to the sun may lead to wrinkles, dryness, and cancer. Older people may bruise more easily, and it can take longer for these bruises to heal. Some medicines or illnesses may also cause bruising. Gravity can cause skin to sag and wrinkle, and smoking can wrinkle skin as well. Also, seen in older adulthood are age spots, previously called “liver spots”. They look like flat, brown spots and are often caused by years in the sun. Skin tags are small, usually flesh-colored growths of skin that have a raised surface. They become common as people age, especially for women, but both age spots and skin tags are harmless (NIA, 2015f).

Nearly everyone has hair loss as they age, and the rate of hair growth slows down as many hair follicles stop producing new hair (U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2019). The loss of pigment and subsequent graying begins in middle adulthood and continues during late adulthood. The body and face also lose hair. Facial hair may grow coarser. For women, this often occurs around the chin and above the upper lip. For men, the hair of the eyebrows, ears, and nose may grow longer. Nails, particularly toenails, may become hard and thick. Lengthwise ridges may develop in the fingernails and toenails. However, pits, lines, and changes in the shape or color of fingernails should be checked by a healthcare provider as they can be related to nutritional deficiencies or kidney disease (U.S. National Library of Medicine).

Height and Weight. The tendency to become shorter as one ages occurs among all races and both sexes. Height loss is related to aging changes in the bones, muscles, and joints. A total of 1 to 3 inches in height is lost with aging. People typically lose almost one-half inch every 10 years after age 40, and height loss is even more rapid after age 70. Changes in body weight vary for men and women. Men often gain weight until about age 55 and then begin to lose weight later in life, possibly related to a drop in the male sex hormone testosterone. Women usually gain weight until age 65 and then begin to lose weight. Weight loss later in life occurs partly because fat replaces lean muscle tissue, and fat weighs less than muscle. Diet and exercise are important factors in weight changes in late adulthood (National Library of Medicine, 2014).

Sarcopenia is the loss of muscle tissue as a natural part of aging. Sarcopenia is most noticeable in men, and physically inactive people can lose as much as 3% to 5% of their muscle mass each decade after age 30, but even people who are active still lose muscle (Webmd, 2016). Symptoms include a loss of stamina and weakness, which can decrease physical activity and subsequently shrink muscles further. Sarcopenia typically increases around age 75, but it may also speed up as early as 65 or as late as 80. Factors involved in sarcopenia include a reduction in nerve cells responsible for sending signals to the muscles from the brain to begin moving, a decrease in the ability to turn protein into energy, and not receiving enough calories or protein to sustain adequate muscle mass. Any loss of muscle is important because it lessens strength and mobility, and sarcopenia is a factor in frailty and the likelihood of falls and fractures in older adults. Maintaining strong leg and heart muscles is important for independence. Weight-lifting, walking, swimming, or engaging in other cardiovascular exercises can help strengthen muscles and prevent atrophy.

Sensory Changes in Late Adulthood

Vision. In late adulthood, all the senses show signs of decline, especially among the oldest-old. In the last chapter, you read about the visual changes that were beginning in middle adulthood, such as presbyopia, dry eyes, and problems seeing in dimmer light. By later adulthood, these changes are much more common. Three serious eye diseases are also more common in older adults: cataracts, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Only the first can be effectively cured in most people.

Some typical vision issues that arise along with aging include:

- The lens becomes less transparent, and the pupils shrink.

- The optic nerve becomes less efficient.

- Distant objects become less acute.

- Loss of peripheral vision (the size of the visual field decreases by approximately one to three degrees per decade of life) (Heiting, 2019).

- More light is needed to see, and it takes longer to adjust to a change from light to darkness and vice versa.

- Driving at night becomes more challenging.

- Reading becomes more of a strain, and eye strain occurs more easily.

The majority of people over 65 have some difficulty with vision, but most is easily corrected with prescriptive lenses. Three percent of those 65 to 74 and 8 percent of those 75 and older have hearing or vision limitations that hinder activity. The most common causes of vision loss or impairment are glaucoma, cataracts, age-related macular degeneration, and diabetic retinopathy (Quillen, 1999).

Glaucoma is the loss of peripheral vision, frequently due to a buildup of fluid in the eye that damages the optic nerve. As we age, the pressure in the eye may increase, causing damage to the optic nerve. The exterior of the optic nerve receives input from retinal cells on the periphery, and as glaucoma progresses more and more of the peripheral visual field deteriorates toward the central field of vision. In the advanced stages of glaucoma, a person can lose their sight entirely. Fortunately, glaucoma tends to progress slowly (NEI, 2016b).

Glaucoma is the most common cause of blindness in the U.S. (NEI, 2016b). African Americans over age 40 and everyone else over age 60 have a higher risk for glaucoma. Those with diabetes and with a family history of glaucoma also have a higher risk (Owsley et al., 2015). There is no cure for glaucoma, but its rate of progression can be slowed, especially with early diagnosis. Routine eye exams to measure eye pressure and examination of the optic nerve can detect both the risk and presence of glaucoma (NEI, 2016b). Those with elevated eye pressure are given medicated eye drops. Reducing eye pressure lowers the risk of developing glaucoma or slowing its progression in those who already have it.

Cataracts are a clouding of the lens of the eye. The lens of the eye is made up of mostly water and protein. The protein is precisely arranged to keep the lens clear, but with age, some of the protein starts to clump. As more of the protein clumps together, the clarity of the lens is reduced. While some adults in middle adulthood may show signs of cloudiness in the lens, the area affected is usually small enough not to interfere with vision. More people have problems with cataracts after age 60 (NIH, 2014b), and by age 75, 70% of adults will have problems with cataracts (Boyd, 2014). Cataracts also cause a discoloration of the lens, tinting it more yellow and then brown, which can interfere with the ability to distinguish colors such as black, brown, dark blue, or dark purple.

Risk factors besides age include certain health problems, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity; behavioral factors, such as smoking; and other environmental factors, such as prolonged exposure to ultraviolet sunlight, previous trauma to the eye, long-term use of steroid medication, and a family history of cataracts (NEI, 2016a; Boyd, 2014). Cataracts are treated by removing and replacing the lens of the eye with a synthetic lens. In developed countries, such as the United States, cataracts can be easily treated with surgery.

However, in developing countries, access to such operations is limited, making cataracts the leading cause of blindness in late adulthood in the least developed countries (Resnikoff, Pascolini, Mariotti & Pokharel, 2004). As shown in Figure 10.6, in areas of the world with limited medical treatment for cataracts, people are living more years with a serious disability. For example, of those living in the darkest red color on the map, more than 990 out of 100,00 people have a shortened lifespan due to the disability caused by cataracts.

Macular degeneration (AMD), the loss of clarity in the center field of vision due to the deterioration of the macula, the center of the retina, is the most common cause of blindness in people over the age of 60. Although it does not usually cause total vision loss, the loss of the central field of vision can greatly impair day-to-day functioning.

There are two types of macular degeneration: dry and wet. The dry type is the most common form and occurs when tiny pieces of a fatty protein called drusen form beneath the retina. Eventually, the macular becomes thinner and stops working properly (Boyd, 2016). About 10% of people with macular degeneration have the wet type, which causes more damage to their central field of vision than the dry form. This form is caused by an abnormal development of blood vessels beneath the retina. These vessels may leak fluid or blood causing more rapid loss of vision than the dry form.

The risk factors for macular degeneration include smoking, which doubles your risk (NIH, 2015a); race, as it is more common among Caucasians than African Americans or Hispanics/Latinos; high cholesterol; and a family history of macular degeneration (Boyd, 2016). At least 20 different genes have been related to this eye disease, but there is no simple genetic test to determine your risk, despite claims by some genetic testing companies (NIH, 2015a). At present, there is no effective treatment for the dry type of macular degeneration. Some research suggests that some patients may benefit from a cocktail of certain antioxidant vitamins and minerals, but results are mixed at best. They are not a cure for the disease, nor will they restore the vision that has been lost. This “cocktail” can slow the progression of visual loss in some people (Boyd, 2016; NIH, 2015a). For the wet type, medications that slow the growth of abnormal blood vessels and surgery, such as laser treatment to destroy the abnormal blood vessels, may be used. Unfortunately, only 25% of those with the wet version typically see improvement with these procedures (Boyd, 2016).

Diabetic retinopathy, also known as diabetic eye disease, is a medical condition in which damage occurs to the retina due to diabetes mellitus. It is a leading cause of blindness. Three major treatments for diabetic retinopathy are very effective in reducing vision loss from this disease: laser photocoagulation, medications, and surgery.

Hearing Loss

Hearing Loss is experienced by 25% of people between ages 65 and 74 and 50% of people above age 75.[1] Among those who are in nursing homes, rates are even higher. Older adults are more likely to seek help with vision impairment than with hearing loss, perhaps due to the stereotype that older people who have difficulty hearing are also less mentally alert.

Conductive hearing loss may occur because of age, genetic predisposition, or environmental effects, including persistent exposure to extreme noise over the course of our lifetime, certain illnesses, or damage due to toxins. Conductive hearing loss involves structural damage to the ear, such as failure in the vibration of the eardrum and/or movement of the ossicles (the three bones in our middle ear). Given the mechanical nature by which the sound wave stimulus is transmitted from the eardrum through the ossicles to the oval window of the cochlea, some degree of hearing loss is inevitable. These problems are often dealt with through devices like hearing aids that amplify incoming sound waves to make the vibration of the eardrum and movement of the ossicles more likely to occur.

Presbycusis is a common form of hearing loss in late adulthood that results in a gradual loss of hearing. It runs in families and affects hearing in both ears (NIA, 2015c). Older adults may also notice tinnitus, a ringing, hissing, or roaring sound in the ears. The exact cause of tinnitus is unknown, although it can be related to hypertension and allergies. It may come and go or persist and get worse over time (NIA, 2015c). The incidence of both presbycusis and tinnitus increases with age, and males around the world have higher rates of both (McCormack, Edmondson-Jones, Somerset, & Hall, 2016).

Your auditory system has two jobs: to help you hear and to help you maintain balance. Balance is controlled when the brain receives information from the shifting of hair cells in the inner ear about the body’s position and orientation. With age, the inner ear’s functionality declines, which can lead to problems with balance when sitting, standing, or moving (Martin, 2014).

When the hearing problem is associated with a failure to transmit neural signals from the cochlea to the brain, it is called sensorineural hearing loss. This type of loss accelerates with age and can be caused by prolonged exposure to loud noises, which causes damage to the hair cells within the cochlea.

One disease that results in sensorineural hearing loss is Ménière’s disease. Although not well understood, Ménière’s disease results in a degeneration of inner ear structures that can lead to hearing loss, tinnitus (constant ringing or buzzing), vertigo (a sense of spinning), and an increase in pressure within the inner ear (Semaan & Megerian, 2011). This kind of loss cannot be treated with hearing aids, but some individuals might be candidates for a cochlear implant as a treatment option. Cochlear implants are electronic devices consisting of a microphone, a speech processor, and an electrode array. The device receives incoming sound information and directly stimulates the auditory nerve to transmit information to the brain.

Being unable to hear causes people to withdraw from conversation and others to ignore them or shout. Unfortunately, shouting is usually high-pitched and can be harder to hear than lower tones. The speaker may also begin to use a patronizing form of ‘baby talk’ known as elderspeak (See et al., 1999). This language reflects the stereotypes of older adults as being dependent, demented, and childlike. Hearing loss is more prevalent in men than women. And it is experienced by more white, non-Hispanics than by Black men and women. Smoking, middle ear infections, and exposure to loud noises increase hearing loss.

Other Senses

Taste and Smell. Our sense of taste and smell is part of our chemical sensing system. Our sense of taste, or gustation, appears to age well. Normal taste occurs when molecules that are released by chewing food stimulate taste buds along the tongue, the roof of the mouth, and the lining of the throat. These cells send messages to the brain, where specific tastes are identified. After age 50, we start to lose some of these sensory cells. Most people do not notice any changes in taste until their 60s (NIH: Senior Health, 2016b). Given that the loss of taste buds is very gradual, even in late adulthood, many people are often surprised that their loss of taste is most likely the result of a loss of smell.

Our sense of smell, or olfaction, decreases with age, and problems with the sense of smell are more common in men than in women. Almost 1 in 4 males in their 60s have a disorder with the sense of smell, compared to 1 in 10 women (NIH: Senior Health, 2016b). This loss of smell due to aging is called presbyopia. Olfactory cells are located in a small area high in the nasal cavity. These cells are stimulated via two pathways: when we inhale through the nose or via the connection between the nose and the throat when we chew and digest food. It is a problem with this second pathway that explains why some foods, such as chocolate or coffee, seem tasteless when we have a head cold. There are several types of loss of smell. Total loss of smell, or anosmia, is extremely rare.

Problems with our chemical senses can be linked to other serious medical conditions such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, or multiple sclerosis (NIH: Senior Health, 2016a). Any sudden changes in sensory sensitivity should be checked out. Loss of smell can change a person’s diet, with either a loss of enjoyment of food and eating too little for balanced nutrition or adding sugar and salt to foods that are becoming blander to the palette.

| Disorder | Description |

| Presbyosmia | Smell loss due to aging |

| Hyposmia | Loss of only certain odors |

| Anosmia | Total loss of smell |

| Dysosmia | Change in the perception of odors. Odors are distorted. |

| Phantosmia | Smelling odors that are not present. |

The Jean Mayer Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging (HNRCA), located in Boston, Massachusetts, is one of six human nutrition research centers in the United States supported by the United States Department of Agriculture and Agricultural Research Service. The goal of the HNRCA, which is managed by Tufts University, is to explore the relationship between nutrition, physical activity, and healthy and active aging.

The HNRCA has made significant contributions to U.S. and international nutritional and physical activity recommendations, public policy, and clinical healthcare. These contributions include advancements in the knowledge of the role of dietary calcium and vitamin D in promoting nutrition and bone health, the role of nutrients in maintaining the optimal immune response, the prevention of infectious diseases, the role of diet in prevention of cancer, obesity research, modifications to the Food Guide Pyramid, contribution to USDA nutrient data bank, advancements in the study of sarcopenia, heart disease, vision, brain and cognitive function, front of packaging food labeling initiatives, and research of how genetic factors impact predisposition to weight gain and various health indicators. Research clusters within the HNRCA address four specific strategic areas: 1) cancer, 2) cardiovascular disease, 3) inflammation, immunity, and infectious disease, and 4) obesity.

Research done by T. Colin Campbell M.D., Michael Greger M.D., Neal Bernard M.D. and others have demonstrated the impact of diet upon longevity and quality of life. As discussed in the video below, consumption of less animal based protein has been linked with the slowing of degradation of function which was traditionally seen as part of the normal aging process.

Try It

Touch. Research has found that with age, people may experience reduced or changed sensations of vibration, cold, heat, pressure, and pain (Martin, 2014). Many of these changes are also consistent with a number of medical conditions that are more common among the elderly, such as diabetes. However, there are also changes in touch sensations among healthy older adults. The ability to detect changes in pressure has been shown to decline with age, with more pronounced losses during the 6th decade and diminishing further with advanced age (Bowden & McNelty, 2013). Yet, there is considerable variability, with almost 40% of the elderly showing sensitivity that is comparable to younger adults (Thornbury & Mistretta, 1981). However, the ability to detect the roughness/ smoothness or hardness/softness of an object shows no appreciable change with age (Bowden & McNulty, 2013). Those who show decreasing sensitivity to pressure, temperature, or pain are at risk for injury (Martin, 2014), as they can injure themselves without detecting it.

Pain. According to Molton and Terrill (2014), approximately 60%-75% of people over the age of 65 report at least some chronic pain, and this rate is even higher for those individuals living in nursing homes. Although the presence of pain increases with age, older adults are less sensitive to pain than younger adults (Harkins, Price, & Martinelli, 1986). Farrell (2012) looked at research studies that included neuroimaging techniques involving older people who were healthy and those who experienced a painful disorder. Results indicated that there were age-related decreases in brain volume in those structures involved in pain. Especially noteworthy were changes in the prefrontal cortex, brainstem, and hippocampus.

Women are more likely to report feeling pain than men (Tsang et al., 2008). Women have fewer opioid receptors in the brain, and women also receive less relief from opiate drugs (Garrett, 2015). Because pain serves as an important indicator that there is something wrong, a decreased sensitivity to pain in older adults is a concern because it can conceal illnesses or injuries requiring medical attention.

Chronic health problems, including arthritis, cancer, diabetes, joint pain, sciatica, and shingles, are responsible for most of the pain felt by older adults (Molton & Terrill, 2014). Cancer is a special concern, especially “breakthrough pain,” which is a severe pain that comes on quickly while a patient is already medicated with a long-acting painkiller. It can be very upsetting, and after one attack, many people worry it will happen again. Some older individuals worry about developing an addiction to pain medication, but if the medicine is taken exactly as prescribed, addiction should not be a concern (NIH, 2015b). Lastly, side effects from pain medicine, including constipation, dry mouth, and drowsiness, may occur that can adversely affect the elder’s life.

Some older individuals put off going to the doctor because they think pain is just part of aging and nothing can help. Of course, this is not usually true. Managing pain is crucial to ensure feelings of well-being for the older adult. When chronic pain is not managed, the individual tends to restrict their movements for fear of feeling pain or injuring themselves further. This lack of activity will result in more restriction, further decreased participation, and greater disability (Jensen, Moore, Bockow, Ehde, & Engel, 2011). A decline in physical activity because of pain is also associated with weight gain and obesity in adults (Strine, Hootman, Chapman, Okoro, & Balluz, 2005). Additionally, sleep and mood disorders, such as depression, can occur (Moton & Terrill, 2014). Learning to cope effectively with pain is an important consideration in late adulthood, and working with one’s primary physician or a pain specialist is recommended (NIH, 2015b).

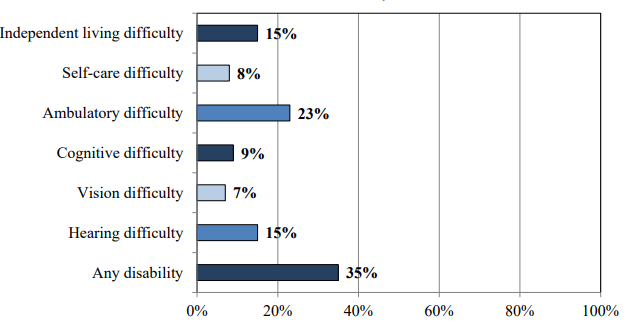

Of those 65 and older, 35% have a disability. Figure 10.11 identifies the percentage of those who have a disability based on the type.

Secondary Aging

Secondary aging refers to changes that are caused by illness or disease. These illnesses reduce independence, impact the quality of life, affect family members and other caregivers, and bring financial burdens. The major difference between primary aging and secondary aging is that primary aging is irreversible and is due to genetic predisposition; secondary aging is potentially reversible and is a result of illness, health habits, and other individual differences.

Chronic Illnesses

In the United States, six in 10 American adults have at least one chronic medical condition, and the number is expected to increase (CDC, 2022). The most common chronic conditions are high blood pressure, arthritis, respiratory diseases like emphysema, and high cholesterol. Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable death and disease in the U.S.

According to research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, chronic disease is also especially a concern in the elderly population in America. Chronic diseases like stroke, heart disease, and cancer are among the leading causes of death among Americans aged 65 or older. While the majority of chronic conditions are found in individuals between the ages of 18 and 64, it is estimated that at least 80% of older Americans are currently living with some form of a chronic condition, with 50% of this population having two or more chronic conditions. The two most common chronic conditions in the elderly are high blood pressure and arthritis, with diabetes, coronary heart disease, and cancer also being reported at high rates among the elderly population. The presence of type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity is termed “metabolic syndrome” and impacts 50% of individuals over the age of 60.

Heart disease is the leading cause of death from a chronic disease for adults older than 65, followed by cancer, stroke, diabetes, chronic lower respiratory diseases, influenza and pneumonia, and, finally, Alzheimer’s disease (which we’ll examine further when we talk about cognitive decline). Though the rates of chronic disease differ by race for those living with chronic illness, the statistics for the leading causes of death among the elderly are nearly identical across racial/ethnic groups.

Heart Disease

As stated above, heart disease is the leading cause of death from chronic disease for adults older than 65. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels. CVD includes coronary artery diseases (CAD) such as angina and myocardial infarction (commonly known as a heart attack). Other CVDs include stroke, heart failure, hypertensive heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, heart arrhythmia, congenital heart disease, valvular heart disease, carditis, aortic aneurysms, peripheral artery disease, thromboembolic disease, and venous thrombosis.

The underlying mechanisms vary depending on the disease. Coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral artery disease involve atherosclerosis. This may be caused by high blood pressure, smoking, diabetes mellitus, lack of exercise, obesity, high blood cholesterol, poor diet, and excessive alcohol consumption, among others. High blood pressure is estimated to account for approximately 13% of CVD deaths, while tobacco accounts for 9%, diabetes 6%, lack of exercise 6%, and obesity 5%.

It is estimated that up to 90% of CVD may be preventable. Prevention of CVD involves improving risk factors through healthy eating, exercise, tobacco smoke avoidance, and alcohol intake. Treating risk factors, such as high blood pressure, blood lipids, and diabetes, is also beneficial. The use of aspirin in otherwise healthy people is of unclear benefit.

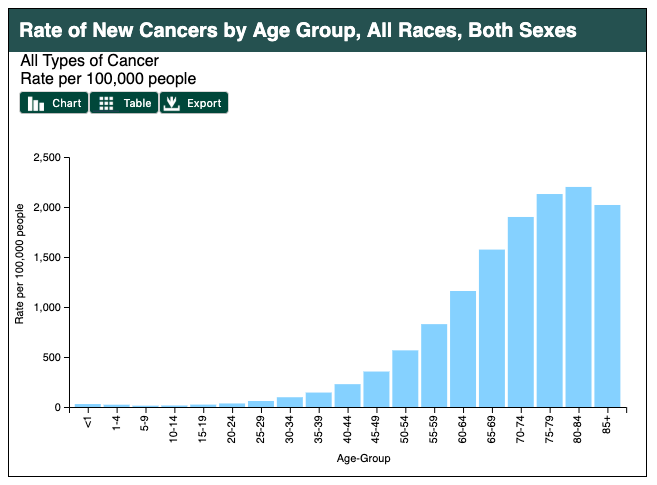

Cancer

Age in itself is one of the most important risk factors for developing cancer. Currently, 60% of newly diagnosed malignant tumors and 70% of cancer deaths occur in people aged 65 years or older. Many cancers are linked to aging; these include breast, colorectal, prostate, pancreatic, lung, bladder, and stomach cancers. Men over 75 have the highest rates of cancer at 28 percent. Women 65 and older have rates of 17 percent. Rates for older non-Hispanic Whites are twice as high as for Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks. The most common types of cancer found in men are prostate and lung cancer. Breast and lung cancer are the most common forms in women.

For many reasons, older adults with cancer have different needs than younger adults with the disease. For example, older adults:

- May be less able to tolerate certain cancer treatments.

- Have a decreased reserve (the capacity to respond to disease and treatment).

- May have other medical problems in addition to cancer.

- May have functional problems, such as the ability to do basic activities of daily living (ADLs: dressing, bathing, eating) or more advanced activities (called instrumental activities of daily living, IADLs, such as using transportation, going shopping or handling finances), and have less available family support to assist them as they go through treatment. IADLs require more complex planning and thinking, whereas ADLs are basic self-care tasks.

- May not always have access to transportation, social support, or financial resources.

- May have different views of quality versus quantity of life

Hypertension and Stroke

Hypertension or high blood pressure and associated heart disease and circulatory conditions increase with age. Stroke is a leading cause of death and severe, long-term disability. Most people who’ve had a first stroke also have high blood pressure (HBP or hypertension). High blood pressure damages arteries throughout the body, creating conditions where they can burst or clog more easily. Weakened arteries in the brain, resulting from high blood pressure, increase the risk for stroke—which is why managing high blood pressure is critical to reducing the chance of having a stroke. Hypertension disables 11.1 percent of 65 to 74-year-olds and 17.1 percent of people over 75. Rates are higher among women and blacks. Rates are highest for women over 75. Coronary disease and stroke are higher among older men than women. The incidence of stroke is lower than that of coronary disease, but it is the No. 5 cause of death and a leading cause of disability in the United States.

Arthritis

While arthritis can affect children, it is predominantly a disease of the elderly. Arthritis is more common in women than men of all ages and affects all races, ethnic groups, and cultures. In the United States, a CDC survey based on data from 2013–2015 showed 22.7% (58.5 million) of adults aged ≥18 years had self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis, and 9.2% (23.7 million or 43.5% of those with arthritis) had arthritis-attributable activity limitation (AAAL) (Barbour et al., 2017). With an aging population, this number is expected to increase.

Arthritis is a term often used to mean any disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, swelling, and decreased range of motion of the affected joints. In some types of arthritis, other organs are also affected. Onset can be gradual or sudden.

There are over 100 types of arthritis. The most common forms are osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease) and rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoarthritis usually increases in frequency with age and affects the fingers, knees, and hips. Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disorder that often affects the hands and feet. Other types include gout, lupus, fibromyalgia, and septic arthritis. They are all types of rheumatic disease

Treatment may include resting the joint and alternating between applying ice and heat. Weight loss and exercise may also be useful. Pain medications such as ibuprofen and paracetamol (acetaminophen) may be used. In some a joint replacement may be useful.

Over time a bent spine can make it hard to walk or even sit up. Adults can prevent the loss of bone mass by eating a healthy diet with enough calcium and vitamin D, regularly exercising, limiting alcohol, and not smoking (National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2016).

Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes (T2D), formerly known as adult-onset diabetes, is a form of diabetes characterized by high blood sugar, insulin resistance, and a relative lack of insulin. Common symptoms include increased thirst, frequent urination, and unexplained weight loss. Symptoms may also include increased hunger, feeling tired, and sores that do not heal. Often symptoms come on slowly. Long-term complications from high blood sugar include heart disease, strokes, and diabetic retinopathy, which can result in blindness, kidney failure, and poor blood flow in the limbs, which may lead to amputations.

Type 2 diabetes primarily occurs as a result of obesity and lack of exercise. Some people are more genetically at risk than others. Type 2 diabetes makes up about 90% of cases of diabetes, with the other 10% due primarily to type 1 diabetes and gestational diabetes. In type 1 diabetes, there is a lower total level of insulin to control blood glucose due to an autoimmune-induced loss of insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. Diagnosis of diabetes is by blood tests such as fasting plasma glucose, oral glucose tolerance test, or glycated hemoglobin (A1C).

Type 2 diabetes is partly preventable by staying a normal weight, exercising regularly, and eating properly. Treatment involves exercise and dietary changes. If blood sugar levels are not adequately lowered, the medication metformin is typically recommended. Many people may eventually also require insulin injections. In those on insulin, routinely checking blood sugar levels is advised; however, this may not be needed in those taking pills. Bariatric surgery often improves diabetes in obese people.

Rates of type 2 diabetes have increased markedly since 1960 in parallel with obesity. As of 2015, there were approximately 392 million people diagnosed with the disease worldwide compared to around 30 million in 1985. Typically it begins in middle or older age, although rates of type 2 diabetes are increasing in young people. Type 2 diabetes is associated with a ten-year-shorter life expectancy.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis, from the Greek word for “porous bones,” is a disease in which bone weakening increases the risk of a broken bone. It is defined as having a bone density of 2.5 standard deviations below that of a healthy young adult. Osteoporosis increases with age as bones become brittle and lose minerals. It is the most common reason for a broken bone among the elderly.

Osteoporosis becomes more common with age. About 15% of white people in their 50s and 70% of those over 80 are affected. It is four times more likely to affect women than men—in the developed world, depending on the method of diagnosis, 2% to 8% of males and 9% to 38% of females are affected. In the United States in 2010, about eight million women and one to two million men had osteoporosis. White and Asian people are at greater risk and are more likely to have osteoporosis than non-Hispanic blacks.

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a long-term degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that mainly affects the motor system, although as the disease worsens, non-motor symptoms become increasingly common. Early in the disease, the most obvious symptoms are shaking, rigidity, slowness of movement, and difficulty with walking, but thinking and behavioral problems may also occur. Dementia becomes common in the advanced stages of the disease, and depression and anxiety also occur in more than a third of people with PD.

The cause of Parkinson’s disease is generally unknown but believed to involve both genetic and environmental factors. Those with a family member affected are more likely to get the disease themselves. There is also an increased risk in people exposed to certain pesticides and among those who have had prior head injuries, while there is a reduced risk in tobacco smokers (though smokers are at a substantially greater risk of stroke) and those who drink coffee or tea. The motor symptoms of the disease result from the death of cells in the substantia nigra, a region of the midbrain, which results in not enough dopamine in these areas. The reason for this cell death is poorly understood but involves the build-up of proteins into Lewy bodies in the neurons.

In 2015, PD affected 6.2 million people and resulted in about 117,400 deaths globally. Parkinson’s disease typically occurs in people over the age of 60, of which about one percent are affected. Males are more often affected than females at a ratio of around 3:2. The average life expectancy following diagnosis is between 7 and 14 years. People with Parkinson’s who have increased the public’s awareness of the condition include actor Michael J. Fox, Olympic cyclist Davis Phinney, and professional boxer Muhammad Ali.

Try It

COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive lung disease in which the airways become damaged, making it difficult to breathe. COPD includes problems such as emphysema and chronic bronchitis (National Institutes of Health: Senior Health, 2013). COPD is one of the leading causes of death. Figure 6 compares healthy to damaged lungs due to COPD. As COPD develops slowly, people may not notice the early signs and may attribute the shortness of breath to age or lack of physical exercise. There is no cure, as the damage cannot be reversed. Treatments aim at slowing further damage.

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of COPD, but other types of tobacco smoking, such as a pipe or cigar, can cause COPD, especially if the smoke is inhaled. Heavy or long-term exposure to secondhand smoke can also lead to COPD (National Institutes of Health: Senior Health, 2013). COPD can also occur in people who have long-term exposure to other environmental irritants, such as chemical fumes and dust from the environment and workplace.

Shingles

According to the National Institute on Aging (2015), Shingles is a disease that affects your nerves (Figure 7). Shingles are caused by the same virus as chicken pox, the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). After you recover from chickenpox, the virus continues to live in some of your nerve cells. It is usually inactive, and most adults live with VZV in their bodies and never get shingles. However, the virus will become active in one in three adults. Instead of causing chickenpox again, it produces shingles. A risk factor for shingles includes advanced age, as people have a harder time fighting off infections as they get older. About half of all shingles cases are in adults age 60 or older, and the chance of getting shingles becomes much greater by age 70. Other factors that weaken an individual’s ability to fight infections, such as cancer, HIV infections, or other medical conditions, can put one at a greater risk for developing shingles.

Shingles results in pain, burning, tingling, or itching in the affected area, as well as a rash and blisters. A shingles vaccine is recommended for those aged 60 and older. Shingles are not contagious, but one can catch chickenpox from someone with shingles.

Attributions

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

References

Aguilar, M., Bhuket, T., Torres, S., Liu, B., & Wong, R. J. (2015). Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the United States, 2003-2012. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 313(19), 1973. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.4260

American Heart Association. (2016). How High Blood Pressure Can Lead to Stroke. https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/health-threats-from-high-blood-pressure/how-high-blood-pressure-can-lead-to-stroke

American Lung Association. (2018). Taking her breath away: The rise of COPD in women. Retrieved from https://www.lung.org/assets/documents/research/rise-of-copd-in-women-full.pdf

American Stroke Association. (n.d.) About Stroke. https://www.strokeassociation.org/en/about-stroke.

Arthritis Foundation. (2017). What is arthritis? Retrieved from http://www.arthritis.org/about-arthritis/understanding- arthritis/what-is-arthritis.php

Ash, A. S., Kroll-Desroisers, A. R., Hoaglin, D. C., Christensen, K., Fang, H., & Perls, T. T. (2015). Are members of long-lived families healthier than their equally long-lived peers? Evidence from the long life family study. Journal of Gerontology: Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. Advance online publication. doi:10.1093/gerona/glv015

Balducci, L., & Extermann, M. (2000). Management of cancer if the older person: A practical approach. The Oncologist. Retrieved from http://theoncologist.alphamedpress.org/content/5/3/224.full

Barnes, S. F. (2011b). Third age-the golden years of adulthood. San Diego State University Interwork Institute. Retrieved from http://calbooming.sdsu.edu/documents/TheThirdAge.pdf

Berger, K. S. (2005). The developing person through the life span (6th ed.). New York: Worth.

Berger, N. A., Savvides, P., Koroukian, S. M., Kahana, E. F., Deimling, G. T., Rose, J. H., Bowman, K. F., & Miller, R. H. (2006). Cancer in the elderly. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, 117, 147-156.

Blank, T. O. (2005). Gay men and prostate cancer: Invisible diversity. American Society of Clinical Oncology, 23, 2593–2596. doi:10.1200/ JCO.2005.00.968

Botwinick, J. (1984). Aging and behavior (3rd ed.). New York: Springer.

Bowden, J. L., & McNulty, P. A. (2013). Age-related changes in cutaneous sensation in the healthy human hand. Age (Dordrecht, Netherlannds), 35(4), 1077-1089.

Boyd, K. (2014). What are cataracts? American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved from http://www.aao.org/eye- health/diseases/what-are-cataracts

Boyd, K. (2016). What is macular degeneration? American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved from http://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/amd-macular-degeneration

Cabeza, R., Anderson, N. D., Locantore, J. K., & McIntosh, A. R. (2002). Aging gracefully: Compensatory brain activity in high- performing older adults. NeuroImage, 17, 1394-1402.

Carlson, N. R. (2011). Foundations of behavioral neuroscience (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2008). Persons age 50 and over: Centers for disease control and prevention. Atlanta, GA: Author.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Percent of U. S. adults 55 and over with chronic conditions. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/health_policy/adult_chronic_conditions.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016b). Older Persons’ Health. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/older-american-health.htm

Cohen, D., & Eisdorfer, C. (2011). Integrated textbook of geriatric mental health. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Cumming, E., & Henry, W. E. (1961). Growing old, the process of disengagement. Basic books.

Dahlgren, D. J. (1998). Impact of knowledge and age on tip-of-the-tongue rates. Experimental Aging Research, 24, 139-153. Dailey, S., & Cravedi, K. (2006). Osteoporosis information easily accessible NIH senior health. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/newsroom/2006/01/osteoporosis-information-easily-accessible-nihseniorhealth

DiGiacomo, R. (2015). Road scholar, once elderhostel, targets boomers. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/nextavenue/2015/10/05/road-scholar-once-elderhostel-targets-boomers/#fcb4f5b64449

Erber, J. T., & Szuchman, L. T. (2015). Great myths of aging. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons. Erikson, E. H. (1982). The life cycle completed. New York, NY: Norton & Company.

Graham, J. (2019, July 10). Why many seniors rate their health positively. The Chicago Tribune, p. 2.

Grzywacz, J. G. & Keyes, C. L. (2004). Toward health promotion: Physical and social behaviors in complete health. Journal of Health Behavior, 28(2), 99-111.

Harkins, S. W., Price, D. D. & Martinelli, M. (1986). Effects of age on pain perception. Journal of Gerontology, 41, 58-63. Harvard School of Public Health. (2016). Antioxidants: Beyond the hype. Retrieved from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/antioxidants

Havighurst, R. J., & Albrecht, R. (1953). Older people.

He, W., Goodkind, D., & Kowal, P. (2016). An aging world: 2015. International Population Reports. U.S. Census Bureau.

He, W., Sengupta, M., Velkoff, V., & DeBarros, K. (2005.). U. S. Census Bureau, Current Popluation Reports, P23-209, 65+ in the United States: 2005 (United States, U. S. Census Bureau). Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p23- 190/p23-190.html

Jensen, M. P., Moore, M. R., Bockow, T. B., Ehde, D. M., & Engel, J. M. (2011). Psychosocial factors and adjustment to persistent pain in persons with physical disabilities: A systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 92, 146–160. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2010 .09.021

Holth, J., Fritschi, S., Wang, C., Pedersen, N., Cirrito, J., Mahan, T.,…Holtzman, D. 2019). The sleep-wake cycle regulates brain interstitial fluid tau in mice and CSF tau in humans. Science, 363(6429), 880-884.

Levant, S., Chari, K., & DeFrances, C. J. (2015). Hospitalizations for people aged 85 and older in the United States 2000-2010. Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db182.pdf

Mayer, J. (2016). MyPlate for older adults. Nutrition Resource Center on Nutrition and Aging and the U. S. Department of Agriculture Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging and Tufts University. Retrieved from http://nutritionandaging.org/my-plate-for-older-adults/

McCormak A., Edmondson-Jones M., Somerset S., & Hall D. (2016) A systematic review of the reporting of tinnitus prevalence and severity. Hearing Research, 337, 70-79.

National Eye Institute. (2016a). Cataract. Retrieved from https://nei.nih.gov/health/cataract/

National Eye Institute. (2016b). Glaucoma. Retrieved from https://nei.nih.gov/glaucoma/

National Institutes of Health. (2011). What is alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency? Retrieved from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/aat

National Institutes of Health. (2014b). Cataracts. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/cataract.html

National Institutes of Health. (2015a). Macular degeneration. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/maculardegeneration.html National Institutes of Health. (2015b). Pain: You can get help. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/pain

National Council on Aging. (2019). Healthy aging facts. Retrieved from https://www.ncoa.org/news/resources-for-reporters/get- the-facts/healthy-aging-facts/

National Institutes of Health. (2016). Quick statistics about hearing. Retrieved from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing

National Institutes of Health: Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. (2014). Arthritis and rheumatic diseases. Retrieved from https://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Arthritis/arthritis_rheumatic.asp

National Institutes of Health: Senior Health. (2013). What is COPD? Retrieved from http://nihseniorhealth.gov/copd/whatiscopd/01.html

National Institutes of Health: Senior Health. (2015). What is osteoporosis? http://nihseniorhealth.gov/osteoporosis/whatisosteoporosis/01.html

National Institutes of Health: Senior Health (2016a). Problems with smell. Retrieved from https://nihseniorhealth.gov/problemswithsmell/aboutproblemswithsmell/01.html

National Institutes of Health: Senior Health (2016b). Problems with taste. Retrieved from https://nihseniorhealth.gov/problemswithtaste/aboutproblemswithtaste/01.html

National Institute on Aging. (2011b). Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging Home Page. (2011). Retrieved from http://www.grc.nia.nih.gov/branches/blsa/blsa.htm

National Institute on Aging. (2015a). The Basics of Lewy Body Dementia. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/publication/lewy-body-dementia/basics-lewy-body-dementia

National Institute on Aging. (2015c). Hearing loss. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/hearing-loss National Institute on Aging. (2015d). Humanity’s aging. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/publication/global- health-and-aging/humanitys-aging

National Institute on Aging. (2015e). Shingles. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/shingles

National Institute on Aging. (2015f). Skin care and aging. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/skin-care- and-aging

National Library of Medicine. (2014). Aging changes in body shape. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003998.htm

National Library of Medicine. (2019). Aging changes in the heart and blood vessels. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004006.htm

National Osteoporosis Foundation. (2016). Preventing fractures. Retrieved from https://www.nof.org/prevention/preventing- fractures/

National Institute on Aging. (2012). Heart Health. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/heart-health

National Institute on Aging. (2015). Shingles. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/shingles

National Institutes of Health: Senior Health. (2013). What is COPD? http://nihseniorhealth.gov/copd/whatiscopd/01.htm

Nilsson, H., Bülow, P.H., Kazemi, A. (2015). Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 2015, Vol. 11(3), doi:10.5964/ejop.v11i3.949.

Office on Women’s Health. (2010b). Sexual health. Retrieved from http://www.womenshealth.gov/aging/sexual-health/

Olanow, C. W., & Tatton, W. G. (1999). Etiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 22, 123-144.

Ortman, J. M., Velkoff, V. A., & Hogan, H. (2014). An aging nation: The older population in the United States. United States Census. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf

Owsley, C., Rhodes, L. A., McGwin Jr., G., Mennemeyer, S. T., Bregantini, M., Patel, N., … Girkin, C. A. (2015). Eye care quality and accessibility improvement in the community (EQUALITY) for adults at risk for glaucoma: Study rationale and design. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14, 1-14. DOI 10:1186/s12939-015-0213-8

Resnikov, S., Pascolini, D., Mariotti, S. P., & Pokharel, G. P. (2004). Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 82, 844-851.

Rhodes, M. G., Castel, A. D., & Jacoby, L. L. (2008). Associative recognition of face pairs by younger and older adults: The role of familiarity-based processing. Psychology and Aging, 23, 239-249.

Ruckenhauser, G., Yazdani, F., & Ravaglia, G. (2007). Suicide in old age: Illness or autonomous decision of the will? Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 44(6), S355-S358.

Schacter, D. L., Church, B. A., & Osowiecki, D. O. (1994). Auditory priming in elderly adults: Impairment of voice-specific implicit memory. Memory, 2, 295-323.

Shokri-Kojori, E., Wang, G., Wiers, C., Demiral, S., Guo, M., Kim, S.,…Volkow, N. (2018). β-amyloid accumulation in the human brain after one night of sleep deprivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(17), 4483-4488.

Strait, J.B., & Lakatta, E.G. (2012). Aging-associated cardiovascular changes and their relationship to heart failure. Heart Failure Clinics, 8(1), 143-164.

Strine, T. W., Hootman, J. M., Chapman, D. P., Okoro, C. A., & Balluz, L. (2005). Health-related quality of life, health risk behaviors, and disability among adults with pain-related activity difficulty. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 2042–2048. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005 .066225

Subramanian, S. V., Elwert, F., & Christakis, N. (2008). Widowhood and mortality among the elderly: The modifying role of neighborhood concentration of widowed individuals. Social Science and Medicine, 66, 873-884.

Sullivan, A. R., & Fenelon, A. (2014). Patterns of widowhood mortality. Journal of Gerontology Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences, 69B, 53-62.

Tales, A., Muir, J. L., Bayer, A., & Snowden, R. J. (2002). Spatial shifts in visual attention in normal aging and dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neuropsychologia, 40, 2000-2012.

Thornbury, J. M., & Mistretta, C. M. (1981). Tactile sensitivity as a function of age. Journal of Gerontology, 36(1), 34-39.

Tsang, A., Von Korff, M., Lee, S., Alonso, J., Karam, E., Angermeyer, M. C., . . . Watanabe, M. (2008). Common persistent pain conditions in developed and developing countries: Gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression- anxiety disorders. The Journal of Pain, 9, 883–891. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005

Uchida, Y., Nakashima, T., Ando, F., Niino, N., & Shimokata, H. (2003). Prevalence of Self-perceived Auditory Problems and their Relation to Audiometric Thresholds in a Middle-aged to Elderly Population. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 123(5), 61

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. (2018). U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on 2020 submission data (1999-2018). www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz, released in June 2021

United States National Library of Medicine. (2019). Aging changes in hair and nails. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004005.htm

Webmd. (2016). Sarcopenia with aging. Retrieved from http://www.webmd.com/healthy- aging/sarcopenia-with-aging

Wilcox, B. J. Wilcox, D. C., & Ferrucci, L. (2008). Secrets of healthy aging and longevity from exceptional survivors around the globe: Lessons from octogenarians to supercentenarians. Journal of Gerontology, 63(11), 1181-1185.

Wu, C., Odden, M. C., Fisher, G. G., & Stawski, R. S. (2016). Association of retirement age with mortality: a population-based longitudinal study among older adults in the USA. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. doi:10.1136/jech- 2015-207097

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Quick Statistics on Hearing. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing. ↵