Section 9: Emerging and Early Adulthood

9.1 What is Emerging Adulthood?

Emerging Adulthood Defined

The theory of emerging (or early/young) adulthood proposes that a new life stage has arisen between adolescence and adulthood over the past half-century in industrialized countries. Fifty years ago, most young people in these countries had entered stable adult roles in love and work by their late teens or early twenties.

Have you noticed that many young adults in industrialized societies today are taking longer to accomplish the developmental tasks of becoming independent in early adulthood? Completion of formal education, financial independence from parents, marriage, and parenthood have all been markers of the end of adolescence and beginning of adulthood, and all of these transitions happen, on average, later now than in the past. The prolonging of adolescence within industrialized countries has prompted the introduction of a new developmental period called emerging adulthood (sometimes called early adulthood) that captures these developmental changes out of adolescence and into adulthood (Arnett, 2000).

Emerging adulthood is the period between the late teens and early twenties, ages 18-25, although some researchers have included up to age 29 in their definitions (Society for the Study of Emerging Adulthood, 2016). Jeffrey Arnett (2000) argues that emerging adulthood is neither adolescence nor is it young adulthood. Individuals in this age period have left behind the relative dependency of childhood and adolescence but have not yet taken on the responsibilities of adulthood. “Emerging adulthood is a time of life when many different directions remain possible, when little about the future is decided for certain, when the scope of independent exploration of life’s possibilities is greater for most people than it will be at any other period of the life course” (Arnett, 2000, p. 469).

Arnett identified five characteristics of emerging adulthood that distinguish it from adolescence and young adulthood (Arnett, 2006).

Age of Identity Exploration

Erik Erikson (1968) commented on a trend during the 20th century of a “prolonged adolescence” in industrialized societies. Today, most identity development occurs during the late teens and early twenties rather than in adolescence. It is during emerging adulthood that many people explore their career choices and ideas about intimate relationships, setting the foundation for adulthood. Emerging adulthood is an extended period of time for exploring what individuals between the ages of 18 and 25 want out of work, love, and life. Part of that exploration is attending postsecondary (tertiary) education to expand more pathways for work. Tertiarty education includes community colleges, universities, and trade schools.

Age of Instability

Exploration generates uncertainty and instability (Arnett, 2000; Arnett, 2006). Emerging adults tend to change jobs, relationships, and residences more frequently than other age groups. Rates of residential change in American society are much higher at ages 18 to 29 than at any other period of life (Arnett, 2003). This reflects the explorations going on in emerging adults’ lives. Some move out of their parents’ household for the first time in their late teens to attend a residential college, whereas others move out simply to be independent (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). They may move again when they drop out of college, change trade schools, or when they graduate. They may move to cohabit with a romantic partner and then move out when the relationship ends. Some move to another part of the country or the world to study or work. For nearly half of American emerging adults, residential change includes moving back in with their parents or guardians at least once (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). In some countries, such as in southern Europe, emerging adults remain in their parents’ homes rather than move out; nevertheless, they may still experience instability in education, work, and love relationships (Douglass, 2020; Douglass, 2007).

Age of Self-focus

Being self-focused is not the same as being “self-centered.” Adolescents are more self-centered than emerging adults. Arnett found emerging adults tend to be very considerate of the feelings of others, especially their parents. They now begin to see their parents as people, not just parents, which is something most adolescents fail to do (Arnett, 2006). Nonetheless, emerging adults focus more on themselves as they realize that they have few obligations to others and that this is the time when they can do what they want with their lives. Most American emerging adults move out of their parent’s home at age 18 or 19 and do not marry or have their first child until at least their late twenties (Arnett, 2003).

Even in countries where emerging adults remain in their parents’ homes through their early twenties, as in southern Europe and in Asian countries such as Japan, they establish a more independent lifestyle than they had as adolescents (Rosenberger, 2007). Emerging adulthood is a time between adolescents’ reliance on parents or primary caregivers and adults’ long-term commitments in love and work, and during these years, emerging adults focus on themselves as they develop the knowledge, skills, and self-understanding they will need for adult life. During emerging adulthood, they tend to make independent decisions about everything, from what to have for dinner to whether or not to get married.

Age of Feeling in-between

When asked if they feel like adults, more 18 to 25-year-olds answer “yes and no” than do teens or adults older than the age of 25 (Arnett, 2004). Most emerging adults have gone through the changes of puberty and are typically no longer in high school, and many have also moved out of their parents’ homes. Thus, they no longer feel as dependent as they did as teenagers. Yet, they may still be financially dependent on their parents or primary caregivers to some degree, and they have not completely attained some of the indicators of adulthood, such as finishing their education, obtaining a “career-based” full-time job, being in a committed relationship, or being responsible for others. It is not surprising that Arnett found that 60% of 18 to 25-year-olds felt that, in some ways, they were adults, but in some ways, they were not (Arnett, 2004). It is when most people reach their late twenties and early thirties that a clear majority feel like they have reached adulthood. Most emerging adults have the subjective feeling of being in a transitional period of life, on the way to adulthood, but not there yet. This “in-between” feeling in emerging adulthood has been found in a wide range of countries, including Argentina (Facio & Micocci, 2003), Austria (Sirsch et al., 2009), Israel (Mayseless & Scharf, 2003), the Czech Republic, (Macek et al., 2007), and China (Nelson & Chen, 2007).

Age of Many Possibilities

This stage tends to be an age of high hopes and great expectations. In one national survey of 18- to 24-year-olds in the United States, nearly all—89%—agreed with the statement, “I am confident that one day I will get to where I want to be in life” (Arnett & Schwab 2012). This optimism in emerging adulthood has been found in other countries as well (Nelson & Chen, 2007). Arnett (2000, 2006) suggests that this optimism is because these dreams have yet to be tested. For example, it is easier to believe that you will eventually find your soulmate when you have yet to have a serious relationship. It may also be a chance to change directions for those whose lives up to this point have been difficult. The experiences of children and teens tend to be heavily influenced by the choices and decisions of their primary caregivers. If their primary caregivers are dysfunctional, there is little a child can do about it. In emerging adulthood, people can move out and move on. They have the chance to transform their lives and move away from unhealthy environments. Even those whose lives were happier and more fulfilling as children now have the opportunity in emerging adulthood to become independent and make decisions about the direction they would like their life to take.

To hear about emerging adulthood and why it may take longer to reach adulthood today in industrialized nations, view this video clip of Dr. Jeffrey Arnett. In the first 6 1/2 minutes, he describes four societal revolutions that may have caused emerging adulthood. In the second half of the clip, Arnett discusses how “30 is the new 20,” as twenty-somethings today enjoy unparalleled freedoms when compared with other generations.

Socioeconomic Class and Emerging Adulthood.

The theory of emerging adulthood was initially criticized as only reflecting upper-middle-class, college-attending young adults in the United States and not those who were working-class or poor (Arnett, 2016). Consequently, Arnett reviewed results from the 2012 Clark University Poll of Emerging Adults, whose participants were demographically similar to the United States population. Results primarily indicated consistencies across aspects of the theory, including positive and negative perceptions of the time period and views on education, work, love, sex, and marriage. Two significant differences were found, the first being that emerging adults from lower socioeconomic classes identified more negativity in their emotional lives, including higher levels of depression. Secondly, those in the lowest socioeconomic group were more likely to agree that they had not been able to find sufficient financial support to obtain the education they believed they needed. Overall, Arnett concluded that emerging adulthood exists wherever there is a period between the end of adolescence and entry into adult roles, but also acknowledged that social, cultural, and historical contexts were important.

Cross-Cultural Variations

The five features proposed in the theory of emerging adulthood were originally based on research involving Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 from various ethnic groups, social classes, and geographical regions (Arnett, 2004, 2016).

To what extent does the theory of emerging adulthood apply internationally?

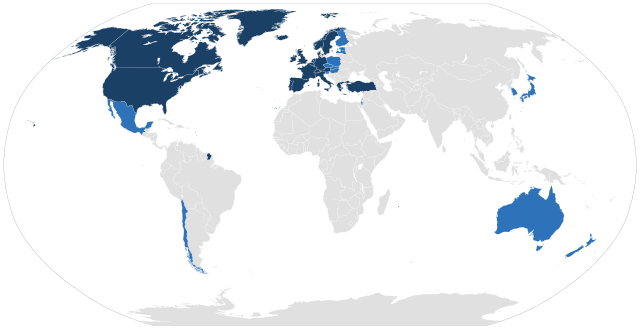

The answer to this question depends greatly on what part of the world is considered. Demographers make a useful distinction between the developing countries that comprise the majority of the world’s population and the economically developed countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), including the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The current population of OECD countries (also called developed countries) is 1.2 billion, about 18% of the total world population (United Nations Development Programme, 2011). The rest of the population resides in developing countries, which have much lower median incomes, much lower median educational attainment, and a much higher incidence of illness, disease, and early death. Let us consider emerging adulthood in other OECD countries, as little is known about the experiences of 18-25-year-olds in developing countries.

The same demographic changes as described above for the United States have taken place in other OECD countries as well. This is true of increasing participation in postsecondary education, as well as increases in the median ages for entering marriage and parenthood (UNdata, 2010). However, there is also substantial variability in how emerging adulthood is experienced across OECD countries. Europe is the region where emerging adulthood is the longest and most leisurely. The median ages for entering marriage and parenthood are near 30 in most European countries (Douglass, 2007).

Europe today is the location of the most affluent, generous, and egalitarian societies in the world, in fact, in human history (Arnett, 2007). Governments pay for tertiary education, assist young people in finding jobs, and provide generous unemployment benefits for those who cannot find work. In northern Europe, many governments also provide housing support. Emerging adults in European societies make the most of these advantages, gradually making their way to adulthood during their twenties while enjoying travel and leisure with friends.

The lives of emerging adults in developed Asian countries, such as Japan and South Korea, are in some ways similar to the lives of emerging adults in Europe and, in some ways, strikingly different. Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults tend to enter marriage and parenthood around the age of 30 (Arnett, 2011). Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults in Japan and South Korea enjoy the benefits of living in affluent societies with generous social welfare systems that provide support for them in making the transition to adulthood, including free university education and substantial unemployment benefits.

However, in other ways, the experience of emerging adulthood in Asian OECD countries is markedly different than in Europe. Europe has a long history of individualism, and today’s emerging adults carry that legacy with them in their focus on self-development and leisure during emerging adulthood. In contrast, Asian cultures have a shared cultural history emphasizing collectivism and family obligations.

Although Asian cultures have become more individualistic in recent decades, as a consequence of globalization, the legacy of collectivism persists in the lives of emerging adults. They pursue identity explorations and self-development during emerging adulthood, like their American and European counterparts, but within narrower boundaries set by their sense of obligations to others, especially their parents (Phinney & Baldelomar, 2011). For example, in their views of the most important criteria for becoming an adult, emerging adults in the United States and Europe consistently rank financial independence among the most important markers of adulthood. In contrast, emerging adults with an Asian cultural background especially emphasize becoming capable of supporting parents financially as among the most important criteria (Arnett, 2003; Nelson et al., 2004). This sense of family obligation may curtail their identity explorations in emerging adulthood to some extent, and compared to emerging adults in the West, they pay more heed to their parent’s wishes about what they should study, what job they should take, and where they should live (Rosenberger, 2007).

Another notable contrast between Western and Asian emerging adults is in their sexuality. In the West, premarital sex is normative by the late teens, more than a decade before most people enter marriage. In the United States and Canada, and in northern and eastern Europe, cohabitation tends to be normative; many people have at least one cohabiting partnership before marriage. In southern Europe, cohabiting is typically still taboo, but premarital sex is more tolerated in emerging adulthood. In contrast, both premarital sex and cohabitation remain rare and forbidden throughout Asia.

For young people in developing countries, emerging adulthood typically only exists for the wealthier segment of society, mainly the urban middle class, whereas the rural and urban poor—the majority of the population—have no emerging adulthood and may even have no adolescence because they enter adult-like work at an early age and also begin marriage and parenthood relatively early. However, as globalization proceeds and economic development along with it, the proportion of young people who experience emerging adulthood will most likely increase as the middle class expands. By the end of the 21st century, emerging adulthood may be normative worldwide.

A Counter Argument: No Emerging Adulthood?

While Arnett describes “emerging adulthood” as a time of delayed entry into early adulthood, not everyone agrees. View this clip from Dr. Meg Jay, as she cautions young adults not to procrastinate since what happens during their twenties is important for the rest of adulthood:

So, When Does Adulthood Begin?

According to Rankin and Kenyon (2008), in years past, the process of becoming an adult was more clearly marked by rites of passage. For many, marriage and parenthood were considered entry into adulthood. However, these role transitions are no longer considered important markers of adulthood (Arnett, 2001). Economic and social changes have resulted in more young adults attending college (Rankin & Kenyon, 2008) and delaying marriage and having children (Arnett & Taber, 1994; Laursen & Jensen-Campbell, 1999). Consequently, current research has found financial independence and accepting responsibility for oneself to be the most important markers of adulthood in Western culture across age (Arnett, 2001) and ethnic groups (Arnett, 2004).

In looking at college students’ perceptions of adulthood, Rankin and Kenyon (2008) found that some students still view rites of passage as important markers. College students who placed more importance on role transition markers, such as parenthood and marriage, belonged to a fraternity/sorority, were traditionally aged (18–25), belonged to an ethnic minority, were of a traditional marital status (i.e., not cohabitating), or belonged to a religious organization, particularly for men. These findings supported the view that people holding collectivist or more traditional values place more importance on role transitions as markers of adulthood. In contrast, older college students and those cohabitating did not value role transitions as markers of adulthood as strongly.

Attributions

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

References

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469-480.

Arnett, J. J. (2001). Conceptions of the transitions to adulthood: Perspectives from adolescence to midlife. Journal of Adult Development, 8, 133-143.

Arnett, J. J. (2003). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 100, 63–75.

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. In J. J. Arnett & N. Galambos (Eds.), Cultural conceptions of the transition to adulthood: New directions in child and adolescent development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Arnett, J. J. (2006). G. Stanley Hall’s adolescence: Brilliance and non-sense. History of Psychology, 9, 186-197.

Arnett, J. J. (2011). Emerging adulthood(s): The cultural psychology of a new life stage. In L.A. Jensen (Ed.), Bridging cultural and developmental psychology: New syntheses in theory, research, and policy (pp. 255–275). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J. (2016). Does emerging adulthood theory apply across social classes? National data on a persistent question. Emerging Adulthood, 4(4), 227-235.

Arnett, J. J., & Taber, S. (1994). Adolescence terminable and interminable: When does adolescence end? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 23, 517–537.

Arnett, J.J. (2007). The long and leisurely route: Coming of age in Europe today. Current History, 106, 130-136.

Douglass, C. B. (2007). From duty to desire: Emerging adulthood in Europe and its consequences. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 101–108.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Laursen, B., & Jensen-Campbell, L. A. (1999). The nature and functions of social exchange in adolescent romantic relationships. In W. Furman, B. B. Brown, & C. Feiring (Eds.), The development of romantic relationships in adolescence (pp. 50–74). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Nelson, L. J., Badger, S., & Wu, B. (2004). The influence of culture in emerging adulthood: Perspectives of Chinese college students. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28, 26–36.

Phinney, J. S. & Baldelomar, O. A. (2011). Identity development in multiple cultural contexts. In L. A. Jensen (Ed.), Bridging cultural and developmental psychology: New syntheses in theory, research and policy (pp. 161-186). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Rankin, L. A. & Kenyon, D. B. (2008). Demarcating role transitions as indicators of adulthood in the 21st century. Who are they? Journal of Adult Development, 15(2), 87-92. doi: 10.1007/s10804-007-9035-2

Rosenberger, N. (2007). Rethinking emerging adulthood in Japan: Perspectives from long-term single women. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 92–95.

Society for the Study of Emerging Adulthood (SSEA). (2016). Overview. Retrieved from http://ssea.org/about/index.htm