Section 11: Late Adulthood

11.1 Introduction to Late Adulthood

What is Late Adulthood?

Late adulthood, which includes those aged 65 years and above, is the fastest-growing age division of the United States population (Gatz, Smyer, & DiGilio, 2016). Currently, one in seven Americans is 65 years of age or older. The first of the baby boomers (born from 1946 to 1964) turned 65 in 2011, and approximately 10,000 baby boomers turn 65 every day.

By the year 2050, almost one in four Americans will be over 65 and will be expected to live longer than previous generations.

Learning Objectives

- Describe age categories of late adulthood

- Explain trends in life expectancies, including factors that contribute to longer life

- Compare theories on why humans age.

- Examine key theories on aging, including socio-emotional selectivity theory (SSC) and selection, optimization, and compensation (SOC)

According to the U. S. Census Bureau (2014b), a person who turned 65 in 2015 can expect to live another 19 years, which is 5.5 years longer than someone who turned 65 in 1950. This increasingly aged population has been referred to as the “graying of America.” This “graying” is already having significant effects on the nation in many areas, including work, health care, housing, social security, caregiving, and adaptive technologies. Table 10.1 shows the 2012, 2020, and 2030 projected percentages of the U.S. population ages 65 and older.

Percent of United States Population 65 Years and Older

| Percent of United States Population | 2012 | 2020 | 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 65 Years and Older | 13.7% | 16.8% | 20.3% |

| 65-69 | 4.5% | 5.4% | 5.6% |

| 70-74 | 3.2% | 4.4% | 5.2% |

| 75-79 | 2.4% | 3.0% | 4.1% |

| 80-84 | 1.8% | 1.9% | 2.9% |

| 85 Years and Older | 1.9% | 2.0% | 2.5% |

Table 1. Adapted from Lally & Valentine-French (2019) and compiled from data from An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf

According to the National Institute on Aging (NIA, 2015b), there are 524 million people over 65 worldwide. This number is expected to increase from 8% to 16% of the global population by 2050. Between 2010 and 2050, the number of older people in less developed countries is projected to increase by more than 250%, compared with only a 71% increase in developed countries. Declines in fertility and improvements in longevity account for the percentage increase for those 65 years and older. In more developed countries, fertility fell below the replacement rate of two live births per woman by the 1970s, down from nearly three children per woman around 1950. Fertility rates also fell in many less developed countries from an average of six children in 1950 to an average of two or three children in 2005. In 2006, fertility was at or below the two-child replacement level in 44 less-developed countries (NIA, 2015d).

Watch this clip from Marco Pahor, a professor in the University of Florida Department of Aging and Geriatric Research, as he discusses his research about ways physical activity affects the mobility of older adults and how it may result in longer life, lower medical costs, and increased long-term independence.

Age Categories

Researchers recognize there are multiple ages or sub-periods that can be distinguished based on differences in peoples’ typical physical health and mental functioning during those age periods by senescence or biological aging (the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics.)

Late adulthood has four age periods: Young–old (60-74), old-old (75-84), the oldest-old (85-99), and centenarians (100+). These categories are based on the conceptions of aging, including biological, psychological, social, and chronological differences. They also reflect the increase in longevity of those living to this latter stage.

The Young Old—65 to 74

These 18.3 million Americans tend to report greater health and social well-being than older adults. 41 percent of this age group report having good or excellent health (Centers for Disease Control, 2004).

Generally, this age span includes many positive aspects and is considered the “golden years” of adulthood. When compared to those who are older, the young-old experience relatively good health and social engagement (Smith, 2000), knowledge and expertise (Singer, Verhaeghen, Ghisletta, Lindenberger, & Baltes, 2003), and adaptive flexibility in daily living (Riediger, Freund, & Baltes, 2005).

Their lives are more similar to those of midlife adults than those of those who are 85 and older. This group is less likely to require long-term care, to be dependent or to be poor, and more likely to be married, working for pleasure rather than income, and living independently. About 65 percent of men and 50 percent of women between the ages of 65 and 69 continue to work full-time (He et al., 2005) and show strong performance in attention, memory, and crystallized intelligence.

Physical activity tends to decrease with age despite the dramatic health benefits enjoyed by those who exercise. People with more education and income are more likely to continue being physically active. Males are more likely to engage in physical activity than females. The majority of the young-old continue to live independently. Only about 3 percent of those 65-74 need help with daily living skills as compared with about 22.9 percent of people over 85. (Another way to think of this is that 97 percent of people between 65 and 74 and 77 percent of people over 85 do not require assistance!) This age group is less likely to experience heart disease, cancer, or stroke than the old but nearly as likely to experience depression (U.S. Census, 2005).

The Old Old—75 to 84

Adults in this age period are likely to be living independently but often experience physical impairments since chronic diseases increase after age 75. For example, congestive heart failure is 10 times more common in people 75 and older than in younger adults (National Library of Medicine, 2019). In fact, half of all cases of heart failure occur in people after age 75 (Strait & Lakatta, 2012). In addition, hypertension and cancer rates are also more common after 75, but because they are linked to lifestyle choices, they typically can be prevented, lessened, or managed (Barnes, 2011b).

Rates of death due to heart disease, cancer, and cerebral vascular disease are double that experienced by people 65-74. Poverty rates are 3 percent higher (12 percent) than for those between 65 and 74. However, the majority of these 12.9 million Americans live independently or with relatives. Widowhood is more common in this group, especially among women.

The Oldest Old—85 plus

Among the older adult population. this age group often includes people who have more serious chronic ailments. In the U.S., the oldest-old represented 14% of the older adult population in 2015 (He et al., 2016). This age group is one of the fastest growing worldwide and is projected to increase more than 300% over its current levels (NIA, 2015b). It is projected that there will be nearly 18 million in the oldest-old age group by 2050, or about 4.5% of the U. S. population, compared with less than 2% of the population today. Females comprise more than 60% of those 85 and older, but they also suffer from more chronic illnesses and disabilities than older males (Gatz et al., 2016).

While this age group accounts for only 2% of the U. S. population, it accounts for 9% of all hospitalizations (Levant et al., 2015). In a study of over 64,000 patients age 65 and older who visited an emergency department, the admission rates increased with age. Thirty-five percent of admissions after an emergency room visit were the young old, almost 43% were the old-old, and nearly half were the oldest-old (Lee et al., 2018). The most common reasons for hospitalization for the oldest-old were congestive heart failure, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, septicemia, stroke, and hip fractures. In recent years, hospitalizations for many of these medical problems have been reduced. However, hospitalization for urinary tract infections and septicemia has increased for those 85 and older Levant et al., 2015). The mortality rate was also higher with age.

Those 85 and older are more likely to require long-term care and to be in nursing homes than the youngest-old. Almost 50% of the oldest-old require some assistance with daily living activities (APA, 2016). However, most still live in the community rather than in a nursing home (Stepler, 2016b). The oldest-old are less likely to be married and living with a spouse compared with the majority of the young-old (APA, 2016; Stepler, 2016c). Gender is also an important factor in the likelihood of being married or living with one’s spouse.

The Centenarians

Centenarians, or people aged 100 or older, are both rare and distinct from the rest of the older population (Figure 4). Although uncommon, the number of people living past the age of 100 is on the rise; between the years 2000 and 2014, the number of centenarians increased by over 43.6%, from 50,281 in 2000 to 72,197 in 2014 (Jiaquan, 2016). In 2010, over half (62.5 percent) of the 53,364 centenarians were age 100 or 101 (US Census Bureau, 2018, August 03).

This number is expected to increase to 601,000 by the year 2050 (U. S. Census Bureau, 2011). The majority is between ages 100 and 104, and eighty percent are women. Out of almost 7 billion people on the planet, about 25 are over 110. Most live in Japan, a few live in the United States, and three live in France (National Institutes of Health, 2006). These “super-centenarians” have led varied lives and probably do not give us any single answer about living longer. Jeanne Clement smoked until she was 117. She lived to be 122. She also ate a diet rich in olive oil and rode a bicycle until she was 100. Her family had a history of longevity. Pitskhelauri (in Berger, 2005) suggests that a moderate diet, continued work, and activity, inclusion in family and community life, and exercise and relaxation are important ingredients for a long life.

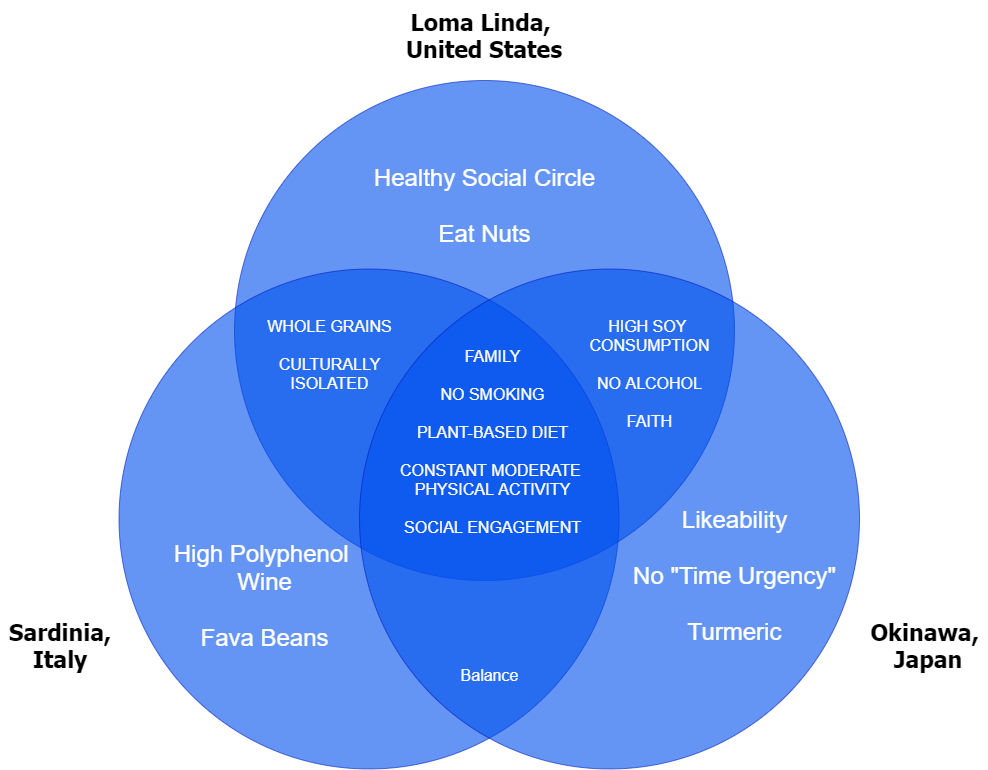

Recent research on longevity reveals that people in some regions of the world live significantly longer than people elsewhere. Efforts to study the common factors between these areas and the people who live there are known as blue zone research. Blue zones are regions of the world where Dan Buettner claims people live much longer than average. The term first appeared in his November 2005 National Geographic magazine cover story, “The Secrets of a Long Life.” Buettner identified five regions as “Blue Zones”: Okinawa (Japan); Sardinia (Italy); Nicoya (Costa Rica); Icaria (Greece); and the Seventh-day Adventists in Loma Linda, California. He offers an explanation, based on data and first-hand observations, for why these populations live healthier and longer lives than others.

The people inhabiting blue zones share common lifestyle characteristics that contribute to their longevity. The Venn diagram below highlights the six characteristics shared by the people of Okinawa, Sardinia, and Loma Linda blue zones. Though not a lifestyle choice, they also live as isolated populations with a related gene pool.

- Family: put ahead of other concerns

- Less smoking

- Semi-vegetarianism: the majority of food consumed is derived from plants

- Constant moderate physical activity: an inseparable part of life

- Social engagement: people of all ages are socially active and integrated into their communities

- Legumes are commonly consumed

In his book, Buettner provides a list of nine lessons covering the lifestyle of blue zones people:

- Moderate, regular physical activity.

- Life purpose.

- Stress reduction.

- Moderate caloric intake.

- Plant-based diet.

- Moderate alcohol intake, especially wine.

- Engagement in spirituality or religion.

- Engagement in family life.

- Engagement in social life.

Try It

The “Graying” Population and Life Expectancy

The term “graying of America” refers to the fact that the American population is steadily becoming more dominated by older people. In other words, the median age of Americans is going up.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017 National Population Projections, 2030 marks an important demographic turning point in U.S. history. By 2030, all baby boomers will be older than 65. This will expand the size of the older population so that 1 in every 5 residents will be at retirement age. And by 2035, it’s projected that there will be 76.7 million people under the age of 18 but 78 million people above the age of 65.

The 2030s are projected to be a transformative decade for the U.S. population. The population is expected to grow at a slower pace, age considerably, and become more racially and ethnically diverse. Net international migration is projected to overtake natural increase in 2030 as the primary driver of population growth in the United States, another demographic first for the United States.

Although births are projected to be nearly four times larger than the level of net international migration in coming decades, a rising number of deaths will increasingly offset how much births are able to contribute to population growth. Between 2020 and 2050, the number of deaths is projected to rise substantially as the population ages and a significant share of the population, the baby boomers, age into older adulthood. As a result, the population will naturally grow very slowly, leaving net international migration to overtake natural increase as the leading cause of population growth, even as projected levels of migration remain relatively constant.

“Graying” Around the World

While the world’s oldest countries are mostly in Europe today, some Asian and Latin American countries are quickly catching up. The percentage of the population aged 65 and over in 2015 ranged from a high of 26.6 percent for Japan to a low of around 1 percent for Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Of the world’s 25 oldest countries, 22 are in Europe, with Germany and Italy leading the ranks of European countries for many years (He et al., 2015).

Slovenia and Bulgaria are projected to be the oldest European countries by 2050. Japan, however, is currently the oldest nation in the world and is projected to retain this position through at least 2050. With the rapid aging taking place in Asia, the countries of South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan are projected to join Japan at the top of the list of oldest countries and areas by 2050, when more than one-third of these Asian countries’ total populations are projected to be aged 65 and over.

Life Expectancy vs Lifespan

Lifespan or Maximum Lifespan is referred to as the greatest age reached by any member of a given population (or species). For humans, the lifespan is currently between 120 and 125. Life Expectancy is defined as the average number of years that members of a population (or species) live. According to the World Health Organization (WHO)(2016), global life expectancy at birth in 2015 was 71.4 years, with females reaching 73.8 years and males reaching 69.1 years. Women live longer than men around the world, and the gap between the sexes has remained the same since 1990. Overall life expectancy ranged from 60.0 years in the WHO African Region to 76.8 years in the WHO European Region. Global life expectancy increased by 5 years between 2000 and 2015, and the largest increase was in the WHO African Region, where life expectancy increased by 9.4 years. This was due primarily to improvements in child survival and access to antiretroviral medication for the treatment of HIV. According to the Central Intelligence Agency (2016) the United States ranks 43rd in the world for life expectancy.

Life Expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live based on the year of birth, current age, and other demographic factors, including gender. The most commonly used measure of life expectancy is at birth (LEB). There are great variations in life expectancy in different parts of the world, mostly due to differences in public health, medical care, and diet, but also affected by education, economic circumstances, violence, mental health, and sex.

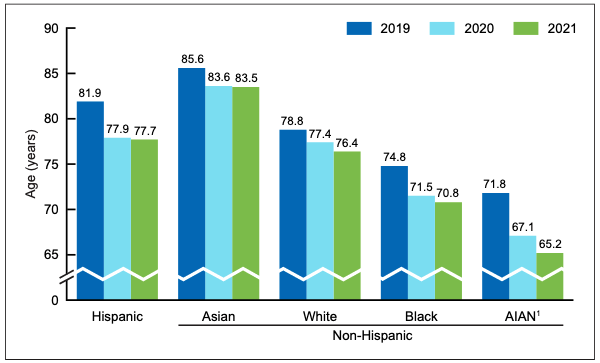

Life Expectancy in the United States

According to the CDC (2022), life expectancy in the U.S. now stands at 76.1 years. Life expectancy dropped 1.8 years in 2020 and 0.9 years in 2021, largely due to the coronavirus pandemic (74% of the decline) and to drug overdoses (fentanyl). Before 2020, life expectancy had been slowly but steadily increasing in the U.S.; its currently at its lowest level since 1996. Women continue to outlive men, with life expectancy being 74.2 years for males and 79.1 years for females. Life expectancy varies according to race and ethnicity. It is highest for Asian Americans, then Hispanics, for both males and females and lower for blacks and American Indians or Alaskan Natives.

Statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau reveal that the 85-and-over age group is the fastest-growing age group in America. According to the Census Bureau and AgingStats.gov, the over-65 population grew from 3 million in 1900 to 40 million in 2010, an increase of more than 1200%. But during this same time, the over-85 population grew from just over 100,000 in 1900 to 5.5 million in 2010–an increase of 5400%!

When calculating life expectancy, we consider all of the elements of heredity, health history, current health habits, and current life experiences that contribute to a longer life or subtract from a person’s life expectancy. Recent studies concluded that cutting calorie intake by 15 percent over two years can slow aging and protect against diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s (Redman et al., 2018).

Some life factors are beyond a person’s control, and some are controllable. The rising cost of health care is a source of financial vulnerability to older adults. Vaccines are especially important for older adults. As you get older, you’re more likely to get diseases like the flu, pneumonia, and shingles and to have complications that can lead to long-term illness, hospitalization, and even death.

Things that contribute to longer life expectancies include eating a healthy diet that is rich in plants and nuts. Staying physically active, not smoking, and consuming moderate amounts of alcohol, tea, or coffee are also reported to be beneficial to leading a long life. Other recommendations include being conscientious, prioritizing your happiness, avoiding stress and anxiety, and having a strong social support network. Establishing a consistent sleep schedule and maintaining between 7-8 hours of sleep per night is also beneficial (Petre, 2019).

A major reason a person will statistically live longer once they reach an older age is simply that they have made it this far without anything killing them. Also, several factors appear to explain changes in life expectancy in the United States and around the world—health conditions are better, many diseases have been eliminated or better controlled through medicine, working conditions are better, and better lifestyle choices are being made. Such factors significantly contribute to longer life expectancies.

Understanding Life Expectancy

Life expectancy is also used in describing the physical quality of life. Quality of life is the general well-being of individuals and societies, outlining negative and positive features of life. Quality of life considers life satisfaction, including everything from physical health, family, education, employment, wealth, safety, security, freedom, religious beliefs, and the environment. According to the CDC (2020), getting adequate physical activity is an evidence-based way to increase quality of life. Learn more about how much activity and types of activities are recommended for older adults in this 4-minute podcast from the CDC.

Increased life expectancy brings concern over the health and independence of those living longer. Greater attention is now being given to the number of years a person can expect to live without disability, which is called active life expectancy. When this distinction is made, we see that although women live longer than men, they are more at risk of living with a disability (Weitz, 2007).

What factors contribute to poor health in women? Marriage has been linked to longevity, but spending years in a stressful marriage can increase the risk of illness. This negative effect is experienced more by women than men and seems to accumulate over the years. The impact of a stressful marriage on health may not occur until a woman reaches 70 or older (Umberson et al., 2006). Sexism can also create chronic stress. The stress experienced by women as they work outside the home as well as care for family members can also ultimately have a negative impact on health (He et al., 2005).

The shorter life expectancy for men, in general, is attributed to greater stress, poorer attention to health, more involvement in dangerous occupations, and higher rates of death due to accidents, homicide, and suicide. Social support can increase longevity. For men, life expectancy and health seem to improve with marriage. Spouses are less likely to engage in risky health practices, and wives are more likely to monitor their husband’s diet and health regimes. However, men who live in stressful marriages can also experience poorer health as a result.

Gender Differences in Life Expectancy

Biological Explanations. Biological differences in sex chromosomes and different patterns of gene expression are theorized as one reason why females live longer. (Chmielewski et al., 2016). Males are heterogametic (XY), whereas females are homogametic (XX) with respect to the sex chromosomes. Males can only express their X chromosome genes that come from the mother, while females have an advantage by selecting the “better” X chromosome from their mother or father while inactivating the “worse” X chromosome. This process of selection for “better” genes is impossible in males and results in the greater genetic and developmental stability of females. In terms of developmental biology, women are the “default” sex, which means that the creation of a male individual requires a sequence of events at a molecular level.

Men are more likely to contract viral and bacterial infections, and their immunity at the cellular level decreases significantly faster with age. Although women are slightly more prone to autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, the gradual deterioration of the immune system is slower in women (Caruso et al., 2013; Hirokawa et al., 2013).

Looking at the influence of hormones, estrogen levels in women appear to have a protective effect on their heart and circulatory system (Viña et al., 2005). Estrogens also have antioxidant properties that protect against the harmful effects of free radicals, which damage cell components, cause mutations, and are, in part, responsible for the aging process. Testosterone levels are higher in men than in women and are related to more frequent cardiovascular and immune disorders. The level of testosterone is also responsible, in part, for male behavioral patterns, including increased levels of aggression and violence (Martin et al., 2011; Borysławski & Chmielewski, 2012).

Another factor responsible for risky behavior is the frontal lobe of the brain. The frontal lobe, which controls judgment and consideration of an action’s consequences, develops more slowly in boys and young men. This lack of judgment affects lifestyle choices, and consequently, many more boys and men die by smoking, excessive drinking, accidents, drunk driving, and violence (Shmerling, 2016).

Lifestyle Factors. Certainly, not all the reasons women live longer than men are biological. As previously mentioned, male behavioral patterns and lifestyle play a significant role in the shorter lifespans for males. One significant factor is that males work in more dangerous jobs, including police, firefighters, and construction, and they are more exposed to violence. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (2014), there were 11,961 homicides in the U.S. in 2014 (last year for full data), and of those, 77% were males. Males are also more than three times as likely to commit suicide (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016a). Further, males serve in the military in much larger numbers than females. According to the Department of Defense (2015), in 2014, 83% of all officers in the Services (i.e., Navy, Army, Marine Corps, and Air Force) were male, while 85% of all enlisted service members were male.

Additionally, men are less likely than women to have health insurance, develop a regular relationship with a doctor, or seek treatment for a medical condition (Scott, 2015; Greenfield et al., 2009). Lastly, social contact is also important, as loneliness is considered a health hazard. Nearly 20% of men over 50 have contact with their friends less than once a month, compared to only 12% of women who see friends infrequently (Scott, 2015). Overall, men’s lower life expectancy appears to be due to both biological and lifestyle factors.

Sexuality

According to Kane (2008), older men and women are often viewed as genderless and asexual. There is a stereotype that elderly individuals no longer engage in sexual activity, and when they do, they are perceived to have committed some kind of offense. These ageist myths can become internalized, and older people have a more difficult time accepting their sexuality (Gosney, 2011). Additionally, some older women indicate that they no longer worry about sexual concerns anymore once they are past the childbearing years.

In reality, many older couples find greater satisfaction in their sex life than they did when they were younger. They have fewer distractions, more time and privacy, no worries about getting pregnant, and greater intimacy with a lifelong partner (National Institutes of Health, 2013). Results from the National Social Life Health and Aging Project indicated that 72% of men and 45.5% of women aged 52 to 72 reported being sexually active (Karraker et al., 2011).

Additionally, the National Survey of Sexual Health data indicated that 20%-30% of individuals remain sexually active well into their 80s (Schick et al., 2010). However, there are issues that occur in older adults that can adversely affect their enjoyment of healthy sexual relationships.

Causes of Sexual Problems

According to the National Institute on Aging (2013), chronic illnesses including arthritis (joint pain), diabetes (erectile dysfunction), heart disease (difficulty achieving orgasm for both sexes), stroke (paralysis), and dementia (inappropriate sexual behavior) can all adversely affect sexual functioning. Hormonal changes, physical disabilities, surgeries, and medicines can also affect a senior’s ability to participate in and enjoy sex. How one feels about sex can also affect performance. For example, a woman who is unhappy about her appearance as she ages may think her partner will no longer find her attractive. A focus on youthful physical beauty for women may get in the way of her enjoyment of sex. Likewise, most men have a problem with erectile dysfunction (ED) once in a while, and some may fear that ED will become a more common problem as they age. If there is a decline in sexual activity for a heterosexual couple, it is typically due to a decline in the male’s physical health (Erber & Szuchman, 2015).

Overall, the best way to experience a healthy sex life in later life is to keep sexually active while aging. However, the lack of an available partner can affect heterosexual women’s participation in a sexual relationship. Beginning at age 40 there are more women than men in the population, and the ratio becomes 2 to 1 at age 85 (Karraker et al., 2011). Because older men tend to pair with younger women when they become widowed or divorced, this also decreases the pool of available men for older women (Erber & Szuchman, 2015).

Theories on Aging

Why do we age?

Why do we age? Many theories attempt to explain how we age, but researchers still do not fully understand what factors contribute to the human lifespan (Jin, 2010). Research on aging is constantly evolving and includes a variety of studies involving genetics, biochemistry, animal models, and human longitudinal studies (NIA, 2011a). According to Jin (2010), modern biological theories of human aging involve two categories.

The first is Programmed Theories that follow a biological timetable, possibly a continuation of childhood development. This timetable would depend on “changes in gene expression that affect the systems responsible for maintenance, repair, and defense responses” (Jin, 2010 p. 72).

The second category includes Damage Theories, which emphasize environmental factors that cause cumulative damage to organisms. We will discuss examples from each of these categories.

Primary Aging: Programmed Theories

Genetics

Genetic make-up certainly plays a role in longevity, but scientists are still attempting to identify which genes are responsible. Based on animal models, some genes promote longer life, while other genes limit longevity.

Specifically, longevity may be due to genes that better equip someone to survive a disease. For others, some genes may accelerate the rate of aging, while others slow that rate. To help determine which genes promote longevity and how they operate, researchers scan the entire genome and compare genetic variants in those who live longer with those who have an average or shorter lifespan. For example, a National Institutes of Health study identified genes possibly associated with blood fat levels and cholesterol, both risk factors for coronary disease and early death (NIA, 2011a). Researchers believe that it is most likely a combination of many genes that affect the rate of aging.

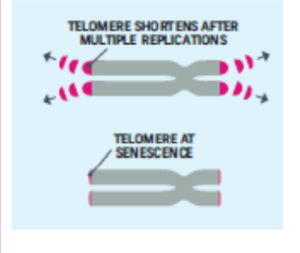

Cellular Clock Theory.

This theory suggests that biological aging is due to the fact that normal cells cannot divide indefinitely. Cells divide a limited number of times and then stop. This is known as the Hayflick limit and is evidenced in cells studied in test tubes, which divide about 40-60 times before they stop (Bartlett, 2014). But what is the mechanism behind this cellular senescence? At the end of each chromosomal strand is a sequence of DNA that does not code for any particular protein but protects the rest of the chromosome, which is called a telomere.

With each replication, the telomere gets shorter. Once it becomes too short, the cell does one of three things.

- It can stop replicating by turning itself off, called cellular senescence.

- It can stop replicating by dying, called apoptosis.

- Or, as in the development of cancer, it can continue to divide and become abnormal.

Senescent cells can also create problems. While they may be turned off, they are not dead, thus they still interact with other cells in the body and can lead to an increase risk of disease. When we are young, senescent cells may reduce our risk of serious diseases such as cancer, but as we age, they increase our risk of such problems (NIA, 2011a).

The question of why cellular senescence changes from being beneficial to being detrimental is still under investigation. The answer may lead to some important clues about the aging process.

DNA Damage

Through the normal growth and aging process, DNA is damaged by environmental factors such as toxic agents, pollutants, and sun exposure (Dollemore, 2006). This results in deletions of genetic material and mutations in the DNA duplicated in new cells. The accumulation of these errors results in reduced functioning in cells and tissues. Theories that suggest that the body’s DNA genetic code contains a built-in time limit for the reproduction of human cells are called the genetic programming theories of aging. These theories promote the view that the cells of the body can only duplicate a certain number of times and that the genetic instructions for running the body can be read only a certain number of times before they become illegible. Such theories also promote the existence of a “death gene,” which is programmed to direct the body to deteriorate and die, and the idea that a long life after the reproductive years is unnecessary for the survival of the species (Kunlin, 2010).

Mitochondrial Damage. Damage to mitochondrial DNA can lead to a decaying of the mitochondria, which is a cell organelle that uses oxygen to produce energy from food. The mitochondria convert oxygen to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) which provides the energy for the cell. When damaged, mitochondria become less efficient and generate less energy for the cell, which can lead to cellular death (NIA, 2011a).

Free Radicals. When the mitochondria use oxygen to produce energy, they also produce potentially harmful byproducts called oxygen free radicals (NIA, 2011a). The free radicals are missing an electron and create instability in surrounding molecules by taking electrons from them. There is a snowball effect (A takes from B, and then B takes from C, etc.) that creates more free radicals, which disrupt the cell and cause it to behave abnormally (See Figure 12). Some free radicals are helpful as they can destroy bacteria and other harmful organisms, but for the most part, they cause damage to our cells and tissue. Free radicals are identified with disorders seen in those of advanced age, including cancer, atherosclerosis, cataracts, and neurodegeneration.

Some research has suggested that adding antioxidants to our diets can help counter the effects of free radical damage because the antioxidants can donate an electron that can neutralize damaged molecules. However, the research on the effectiveness of antioxidants is not conclusive (Harvard School of Public Health, 2016).

Immune and Hormonal Stress Theories

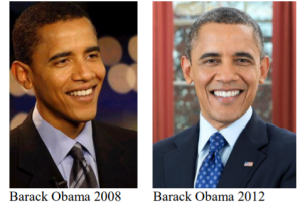

Ever notice how quickly U.S. presidents seem to age? Before and after photos reveal how stress can play a role in the aging process. When gerontologists study stress, they are not just considering major life events, such as unemployment, the death of a loved one, or the birth of a child. They also include metabolic stress, the life-sustaining activities of the body, such as circulating the blood, eliminating waste, controlling body temperature, and neuronal firing in the brain. In other words, all the activities that keep the body alive also create biological stress.

To understand how this stress affects aging, researchers note that both problems with the innate and adaptive immune systems play key roles. The innate immune system is made up of the skin, mucous membranes, cough reflex, stomach acid, and specialized cells that alert the body of an impending threat. With age, these cells lose their ability to communicate effectively, making it harder for the body to mobilize its defenses. The adaptive immune system includes the tonsils, spleen, bone marrow, thymus, circulatory system and the lymphatic system that work to produce and transport T cells. T-cells, or lymphocytes, fight bacteria, viruses, and other foreign threats to the body. T-cells are in a “naïve” state before they are programmed to fight an invader and become “memory cells”. These cells now remember how to fight a certain infection should the body ever come across this invader again. Memory cells can remain in your body for many decades, which is why the measles vaccine you received as a child is still protecting you from this virus today. As older adults produce fewer new T-cells to be programmed, they are less able to fight off new threats, and new vaccines work less effectively. The reason why the shingles vaccine works well with older adults is because they already have some existing memory cells against the varicella virus. The shingles vaccine is acting as a booster (NIA, 2011a).

Hormonal Stress Theory, also known as the Neuroendocrine Theory of Aging, suggests that as we age, the ability of the hypothalamus to regulate hormones in the body begins to decline, leading to metabolic problems (American Federation of Aging Research (AFAR) 2011). This decline is linked to excessive levels of the stress hormone cortisol. While many of the body’s hormones decrease with age, cortisol does not (NIH, 2014a). The more stress we experience, the more cortisol we release, and the more hypothalamic damage that occurs. Changes in hormones have been linked to several metabolic and hormone-related problems that increase with age, such as diabetes (AFAR, 2011), thyroid problems (NIH, 2013), osteoporosis, and orthostatic hypotension (NIH, 2014a).

Secondary Aging: Damage Theories

A second set of theories focuses on aging as an outcome of the wear and tear our bodies receive as part of our daily lives. Damage theories examine the parts of aging and death that come from the outside. This perspective scrutinizes the nurture or environmental side of the equation and holds that the body wears out through the cumulative effects of a host of life events and lifestyle factors, such as disease, disuse, abuse, stress, and environmental toxins. Evidence to support this position comes from three sources.

Lifestyle Factors that Predict Aging and Death

The first body of research supporting the role of nurture in aging examines the effects of a variety of physical factors, such as poor diet, lack of exercise, and substance abuse, as well as psychological factors, such as stress, social inactivity, and pessimistic outlook. Studies show that these factors can predict both how healthy people will be and how long they will live. Such forces can cause biological damage, which is repaired more and more slowly as we age. From this perspective, aging results from the accumulation of such damage.

Exposure to Environmental Toxins

A second body of evidence shows that aging can be shaped by exposure to environmental pollution, as caused, for example, by pesticides, air pollutants, and radiation or by harmful substances added to our food and water. When we metabolize these toxins, they do damage not only to our bodies but also to our our genetic DNA material at the cellular level. As our organ systems deteriorate and become more vulnerable, errors pile up, and our body’s ability to repair them slows down. Toxins can cause allergic reactions and auto-immune diseases, as seen in the upswing in Type II adult-onset diabetes and other chronic conditions. Effects of environmental toxins are also seen in inflammatory processes involved in life-threatening medical conditions like cardiovascular disease, arthritis, and cancer.

Historical Increases in Average Life Expectancy

A third source of evidence that aging can be speeded up or slowed down by external factors comes from documentation of steady historical increases in average life expectancy. These increases follow from changes in external factors, mostly related to public health. They include historical reductions in the number of people in extreme poverty as well as improvements in nutrition, quality, and access to medical care, sanitation, childbirth procedures, and the invention of antibiotics. These historical changes did not result in evolutionary changes in human biology. They produced recent changes in environmental factors that are shaping the rate of aging and the timing of death.

In sum, as you can see, aging and death are processes that are multiply determined– by biological, psychological, social, and contextual factors. Theories of primary aging are correct that we have the seeds of our aging programmed into our bodies. But theories of secondary aging are also correct– the environment also speeds up and slows down our aging and dying via the damage it does to our increasingly vulnerable biology. And, of course, lifespan researchers would remind us that the active individual also plays a role through the decisions they make about behavioral risks, like smoking, drinking, and using or abusing substances, as well as via more positive routes, especially a healthy diet, exercise, and continued participation in positive social and cognitive activities.

Successful Aging

We are considered in late adulthood from the time we reach our mid-sixties until death. Because we live longer, late adulthood gets longer. Whether we start counting at 65, as demographers may suggest, or later, there is a greater proportion of people alive in late adulthood than at any other time in world history. Today, a 10-year-old child has a 50 percent chance of living to age 104. Some demographers have even speculated that the first person ever to live to be 150 is alive today.

Demographers use chronological age categories to classify individuals in late adulthood. Developmentalists, however, divide this population into categories based on physical and psychosocial well-being in order to describe one’s functional age. As we learned above, the “young old” are healthy and active, the “old, old” experience some health problems and difficulty with daily living activities, and the “oldest old” are frail and often in need of care. A 98-year-old woman who still lives independently, has no major illnesses, and is able to take a daily walk would be considered as having a functional age of “young old”. Therefore, optimal aging refers to those who enjoy better health and social well-being than average (Figure 2). Normal aging refers to those who seem to have the same health and social concerns as most of those in the population. However, there is still much being done to understand exactly what normal aging means. Impaired aging refers to those who experience poor health and dependence to a greater extent than would be considered normal.

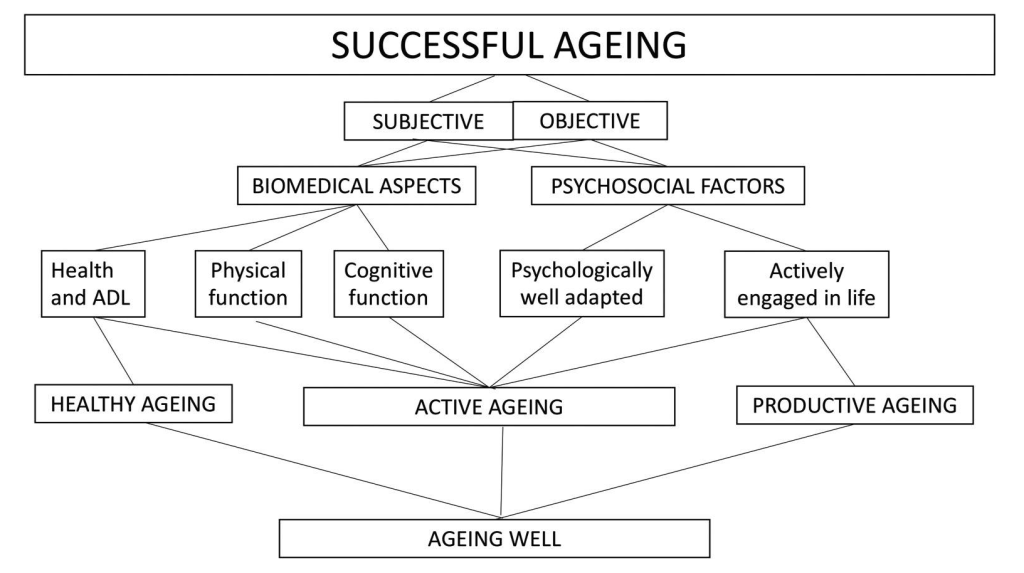

Successful aging is a concept that describes the quality of aging. Studies continually use a variety of definitions for “successful aging.” For this book, “successful aging” is defined as encompassing an individual’s physical, functional, social, and psychological health domains (Cosco et al., 2014; Fries, 1980; Martin et al., 2015; Depp & Jeste, 2006). Most definitions of “successful aging” also include objective measurements of outcomes based on an individual’s overall health and functionality (Fernández-Ballesteros, 2019). Because a variety of terms and dimensions of successful aging are used, we have included Figure 12 as a brief overview.

Although definitions of successful aging are value-laden, Rowe and Kahn (1997) defined three criteria of successful aging that are useful for research and behavioral interventions. They include:

- Relative avoidance of disease, disability, and risk factors, like high blood pressure, smoking, or obesity

- Maintenance of high physical and cognitive functioning

- Active engagement in social and productive activities

For example, research has demonstrated that age-related declines in cognitive functioning across the adult lifespan may be slowed through physical exercise and lifestyle interventions (Rowe & Kahn, 1997).

Successful aging involves making adjustments as needed to continue living as independently and actively as possible. This is referred to as selective optimization with compensation. Let’s review this theory and consider a few additional theories on successful aging.

Theories of Successful Aging

Psychologists and sociologists have long wondered how people manage to age successfully, and many theories have been developed that highlight the keys to successful aging. We examine five: (1) Activity theory, (2) Continuity theory, (3) Socioemotional selectivity theory, (4) Selective optimization with compensation, and (5) Developmental self-regulation theory.

Activity Theory

Developed by Havighurst and Albrecht in 1953, activity theory addresses the issue of how persons can best adjust to the changing circumstances of old age–e.g., retirement, illness, loss of friends and loved ones through death, and so on. In addressing this issue, they recommend that older adults involve themselves in voluntary and leisure organizations, child care, and other forms of social interaction. Activity theory thus strongly supports the avoidance of a sedentary lifestyle and considers it essential to health and happiness that the older person remains active physically and socially. In other words, the more active older adults are, the more stable and positive their self-concept will be, which will then lead to greater life satisfaction and higher morale (Havighurst & Albrecht, 1953). Activity theory suggests that many people are barred from meaningful experiences as they age, but older adults who continue to find ways to remain active can work toward replacing lost opportunities with new ones (Nilsson et al., 2015).

Continuity theory

Continuity theory suggests as people age, they continue to view the self in much the same way as they did when they were younger. An older person’s approach to problems, goals, and situations is much the same as it was when they were younger. They are the same individuals, but simply in older bodies. Consequently, older adults continue to maintain their identity even as they give up previous roles. For example, a retired Coast Guard commander attends reunions with shipmates, stays interested in new technology for home use, is meticulous in the jobs he does for friends or at church, and displays mementos from his experiences on the ship. He is able to maintain a sense of self as a result. People do not give up who they are as they age. Hopefully, they are able to share these aspects of their identity with others throughout life. Focusing on what a person is still able to do and pursuing those interests and activities is one way to optimize and maintain self-identity.

Socioemotional Selectivity Theory

The Socioemotional Selectivity Theory focuses on changes in motivation for actively seeking social contact with others (Carstensen, 1993; Carstensen, Isaacowitz & Charles, 1999). This theory proposes that with increasing age, our motivational goals change based on how much time we have left to live. Rather than focusing on acquiring information from many diverse social relationships, as adolescents and young adults tend to do, older adults focus on the emotional aspects of relationships. To optimize the experience of positive affect, older adults actively restrict their social life to prioritize time spent with emotionally close significant others. In line with this theory, older marriages are found to be characterized by enhanced positive and reduced negative interactions, and older partners show more affectionate behavior during conflict discussions than middle-aged partners (Carstensen, Gottman, & Levenson, 1995). Research showing that older adults have smaller networks compared to young adults and tend to avoid negative interactions also supports this theory.

Return to Psychosocial Development in Middle Adulthood for more on the Socioemotional Selectivity Theory

Selective Optimization with Compensation

Selective Optimization with Compensation is a strategy for improving health and well-being in older adults and a model for successful aging. It is recommended that seniors select and optimize their best abilities and most intact functions while compensating for declines and losses. This means, for example, that a person who can no longer drive is able to find alternative transportation or a person who is compensating for having less energy learns how to reorganize the daily routine to avoid over-exertion. Perhaps nurses and other allied health professionals working with this population will begin to focus more on helping patients remain independent by optimizing their best functions and abilities rather than simply treating illnesses. Promoting health and independence is essential for successful aging.

Return to Psychosocial Development in Middle Adulthood for more on the Selective Optimization with Compensation Theory

Developmental Self-regulation Theory

Developmental Self-regulation Theory is a dual-process model that could have been based on St. Augustine’s serenity prayer. On the one hand, is primary control, or the strength and courage to take action to change the things that can be changed. This includes a sense of self-efficacy to take action needed to make lifestyle changes or undergo treatments that optimize functioning, such as a healthy diet, exercise, medical treatments (like taking one’s insulin or cataract surgery), or adopting outside aids like a cane or walker. The second process is called accommodation, and it involves the grace to accept the things that cannot be changed. This attitude of willing acceptance includes understanding, gratitude for times past, and a focus on the positive things that still remain. Such accommodation can be contrasted with furious resentment or depressed resignation to the losses of aging. In fact, some researchers argue that depression in old age is often due not to the losses of control aging inevitably entails but to an inability to accommodate, that is, to relinquish activities and goals that are no longer feasible.

Systematic examination of old age is a new field inspired by the unprecedented number of people living long enough to become elderly. Developmental psychologists Paul and Margret Baltes have proposed a model of adaptive competence for the entire life span, but the emphasis here is on old age. Their model SOC (Selection, Optimization, and Compensation) is illustrated with engaging vignettes of people leading fulfilling lives, including writers Betty Friedan and Joan Erikson, as well as dancer Bud Mercer. Segments of the cognitive tests used by the Baltes in assessing the mental abilities of older people are shown. Although the video clip shown below is old and dated, it remains an intellectually appealing video in which the Baltes discuss personality components that generally lead to positive aging experiences.

Try It

Additional Resources

American Psychological Association: A Snapshot of Today’s Older Adults

Attributions

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

The section on the “graying” of America is from Waymaker Lifespan Development, authored by Sonja Ann Miller for Lumen Learning, and is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license.

Some selections were adapted from The Noba Project.

References

American Federation for Aging Research. (2011). The biology of aging: Why our bodies grow old. Retrieved from https://www.afar.org/brochure/the-biology-of-aging

Baltes, B. B., & Dickson, M. W. (2001). Using life-span models in industrial-organizational psychology: The theory of selective optimization with compensation. Applied Developmental Science, 5(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532480xads0501_5

Bartlett, J. E. (2014). Nursing theories: A framework for professional practice (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Berger, K. S. (2005). The developing person through the life span (6th ed.). New York: Worth.

Borysławski, K., & Chmielewski, P. (2012). A prescription for healthy aging. In: A Kobylarek (Ed.), Aging: Psychological, biological and social dimensions (pp. 33-40). Wrocław: Agencja Wydawnicza.

Caruso, C., Accardi, G., Virruso, C., & Candore, G. (2013). Sex, gender and immunosenescence: a key to understand the different lifespan between men and women? Immunity & Ageing: I & A, 10(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4933-10-20

Central Intelligence Agency. (2016). The world factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the- world-factbook/geos/xx.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016a). Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db241.htm

Chapman, D. P., Williams, S. M., Strine, T. W., Anda, R. F., & Moore, M. J. (2006, February 18). Preventing Chronic Disease: April 2006: 05_0167. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2006/apr/05_0167.htm

Chmielewski, P., Borysławski, K., & Strzelec, B. (2016). Contemporary views on human aging and longevity. Anthropological Review, 79(2), 115–142. https://doi.org/10.1515/anre-2016-0010

Cosco, T. D., Prina, A. M., Perales, J., Stephan, B. C. M., & Brayne, C. (2014). Operational definitions of successful aging: a systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(3), 373–381. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610213002287

Department of Defense. (2015). Defense advisory committee on women in the services. http://dacowits.defense.gov/Portals/48/Documents/Reports/2015/Annual%20Report/2015%20DACOWITS%20Annual %20Report_Final.pdf

Depp, C. A., & Jeste, D. V. (2006). Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(1), 6–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jgp.0000192501.03069.bc

Dollemore, D. (2006, August 29). Publications. National Institute on Aging. Retrieved May 07, 2011, from http://www.nia.nih.gov/HealthInformation/Publications?AgingUndertheMicroscope/

Erber, J. T., & Szuchman, L. T. (2015). Great myths of aging. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2014). Crime in the United States. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the- u.s/2014/crime-in-the-u.s.-2014/tables/expanded- homicide- data/expanded_homicide_data_table_1_murder_victims_by_race_ethnicity_and_sex_2014.xls

Fernández-Ballesteros, R. (2019). The concept of successful aging and related terms. In The Cambridge Handbook of Successful Aging (pp. 6–22). Cambridge University Press.

Fries, J. F. (1980). Aging, natural death, and the compression of morbidity. The New England Journal of Medicine, 303(3), 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198007173030304

Greenfield, E. A., Vaillant, G. E., & Marks, N. F. (2009). Do formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions have independent linkages with diverse dimensions of psychological well-being? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50, 196-212.

Gosney, T. A. (2011). Sexuality in older age: Essential considerations for healthcare professionals. Age Ageing, 40(5), 538-543.

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (2016). Antioxidants. Retrieved from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/antioxidants/

He, W., Sengupta, M., Velkoff, V., & DeBarros, K. (n.d.). U. S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P23‐209, 65+ in the United States: 2005 (United States, U. S. Census Bureau). www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p23‐190/p23‐190.html

Hirokawa, K., Utsuyama, M., Hayashi, Y., Kitagawa, M., Makinodan, T., & Fulop, T. (2013). Slower immune system aging in women versus men in the Japanese population. Immunity & Ageing: I & A, 10(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4933-10-19

Jiaquan, X. (2016). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mortality Among Centenarians in the United States, 2000─2014. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db233.pdf.

Jin, K. (2010). Modern biological theories of aging. Aging and Disease, 1(2), 72-74. https://doi.org/10.14336/AD.2010.0100072

Jin, Y., Pang, A., & Cameron, G. T. (2010). The role of emotions in crisis responses: Inaugural test of the integrated crisis mapping (ICM) model. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 15(4), 428-452. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563281011085529

Kane, M. (2008). How are the sexual behaviors of older women and older men perceived by human service students? Journal of Social Work Education, 27(7), 723-743.

Karraker, A., DeLamater, J., & Schwartz, C. R. (2011). Sexual frequency declines from midlife to later life. The Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66B, 502-512.

Levant, S., Chari, K., & DeFrances, C. J. (2015). Hospitalizations for people aged 85 and older in the United States 2000-2010. Centers for Disease Control. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db182.pdf

Martin, P., Kelly, N., Kahana, B., Kahana, E., Willcox, B. J., Willcox, D. C., & Poon, L. W. (2015). Defining successful aging: a tangible or elusive concept? The Gerontologist, 55(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu044

Martin, P., Poon, L. W., & Hagberg, B. (2011). Behavioral factors of longevity. Journal of Aging Research, 2011, 197590. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/197590

National Institute on Aging. (2011a). Cellular senescence: Its role in aging and health. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/cellular-senescence-its-role-aging-and-health

National Institute on Aging. (2011). Does cellular senescence hold secrets for healthier aging?. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/does-cellular-senescence-hold-secrets-healthier-aging

National Institutes of Health. (2013). Hypothyroidism. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health- topics/endocrine/hypothyroidism/Pages/fact-sheet.aspx

Newsroom: Facts for Features & Special Editions: Facts for Features: Older Americans Month: May 2010. (2011, February 22). Census Bureau Home Page. http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/cb10-ff06.html

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37(4), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.4.433

Shmerling, R. H. (2016). Why men often die earlier than women. Harvard Health Publications. http://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/why-men-often-die-earlier-than-women-201602199137

Scott, P. J. (2015). Save the Males. Men’s Health. http://www.menshealth.com

Schick, V., Herbenick, D., Reece, M., Sanders, S. A., Dodge, B., Middlestadt, S. E., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2010). Sexual behaviors, condom use, and sexual health of Americans over 50: Implications for sexual health promotion for older adults. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(5), 315-329.

Tan, K. & Tay, L. (2024). Relationships and well-being. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/h2tu6sxn

US Census Bureau. (2018, October 05). Population Projections. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popproj.html

US Census Bureau. (2018, December 03). Older People Projected to Outnumber Children. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/cb18-41-population-projections.html

US Census Bureau. (2018, April 10). The Nation’s Older Population Is Still Growing, Census Bureau Reports. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2017/cb17-100.html

US Census Bureau. (2018, August 03). Newsroom. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/cb17-ff08.html

United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p95-16-1.pdf. World Health Organization. (2016). Life expectancy. http://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/life_tables/situation_trends_text/en/

Viña, J., Borrás, C., Gambini, J., Sastre, J., & Pallardó, F. V. (2005). Why females live longer than males: control of longevity by sex hormones. Science of Aging Knowledge Environment: SAGE KE, 2005(23), e17. https://doi.org/10.1126/sageke.2005.23.pe17

Wan, H., Goodking, D., and Kowal, P. (2015). An Aging World: 2015.