Section 8: Adolescence

8.1 Physical Development in Adolescence

What are the physical changes that occur during puberty and adolescence?

Physical changes of puberty mark the onset of adolescence (Lerner & Steinberg, 2009). For both boys and girls, these changes include a growth spurt in height, growth of pubic and underarm hair, and skin changes (e.g., pimples). Boys also experience growth in facial hair and a deepening of their voice. Girls experience breast development and begin menstruating. These pubertal changes are driven by hormones, particularly an increase in testosterone for boys and estrogen for girls. The physical changes that occur during adolescence are greater than those of any other time of life, with the exception of infancy. In some ways, however, the changes in adolescence are more dramatic than those that occur in infancy—unlike infants, adolescents are aware of the changes that are taking place and of what the changes mean. In this section, you will learn about the pubertal changes in body size, proportions, and sexual maturity, the social and emotional attitudes and reactions toward puberty, and some of the health concerns during adolescence, including eating disorders.

Adolescence has evolved historically, with evidence indicating that this stage is lengthening as individuals start puberty earlier and transition to adulthood later than in the past. Puberty today begins, on average, at age 10–11 years for girls and 11–12 years for boys. This average age of onset has decreased gradually over time since the 19th century by 3–4 months per decade, which has been attributed to a range of factors, including better nutrition, obesity, increased father absence, and other environmental factors (Steinberg, 2013). Completion of formal education, financial independence from parents, marriage, and parenthood have all been markers of the end of adolescence, and beginning of adulthood, and all of these transitions happen, on average, later now than in the past. In fact, the prolonging of adolescence has prompted the introduction of a new developmental period called emerging adulthood that captures these developmental changes out of adolescence and into adulthood, occurring from approximately ages 18 to 29 (Arnett, 2000). We’ll learn more about this phase in the next module.

Learning Objectives

- Summarize the overall physical growth

- Describe pubertal changes in body size, proportions, and sexual maturity

- Describe the changes in brain maturation

- Explain the importance of sleep for adolescents

- Describe health and sexual development during adolescence

- Explain social and emotional attitudes and reactions toward puberty, including sex differences

- Discuss concerns associated with eating disorders

Physical Development during Adolescence

In the United States, puberty typically begins, on average, at age 10–11 years for females and 11–12 years for males. Pubertal changes take around three to four years to complete. While the sequence of physical changes in puberty is predictable, the onset and pace of puberty vary widely. Every person’s individual timetable for puberty is different and is primarily influenced by heredity; however, environmental factors—such as diet and exercise—also exert some influence.

Physical Growth Spurt

Adolescents experience an overall physical growth spurt. The growth proceeds from the extremities toward the torso. This is referred to as distal proximal development. First, the hands grow, then the arms, and finally, the torso. The overall physical growth spurt results in 10-11 inches of added height and 50 to 75 pounds of increased weight. The head begins to grow sometime after the feet have gone through their period of growth. Growth of the head is preceded by growth of the ears, nose, and lips. The difference in these patterns of growth results in adolescents appearing awkward and out of proportion. As the torso grows, so does the internal organs. The heart and lungs experience dramatic growth during this period.

During this stage, children are quite similar in height and weight. However, gender differences become apparent during adolescence. From approximately age 10 to 14, the average female is taller but not heavier than the average male. For females the growth spurt begins between 8 and 13 years old (average 10-11), with adult height reached between 10 and 16 years old. After that, the average male becomes both taller and heavier, although individual differences are certainly noted. Males tend to begin their growth spurt slightly later, usually between 10 and 16 years old (average 12-13), and typically reach their adult height between 13 and 17 years old. As adolescents physically mature, weight differences are more noteworthy than height differences. At eighteen years of age, those who are heaviest weigh almost twice as much as the lightest, but the tallest teens are only about 10% taller than the shortest (Seifert, 2012). Both nature (i.e., genes) and nurture (e.g., nutrition, medications, and medical conditions) can influence both height and weight.

Both height and weight can certainly be sensitive issues for some teenagers. Yet, neither socially preferred height nor thinness is the destiny for many individuals. Being overweight, in particular, has become a common, serious problem in modern society due to the prevalence of diets high in fat and lifestyles low in activity (Tartamella et al., 2004).

Average height and weight are also related somewhat to racial and ethnic background. In general, children of Asian background tend to be slightly shorter than children of European and North American background. The latter, in turn, tend to be shorter than children from African societies (Eveleth & Tanner, 1990). Body shape differs slightly as well, though the differences are not always visible until after puberty. Asian background youth tend to have arms and legs that are a bit short relative to their torsos, and African background youth tend to have relatively long arms and legs. The differences are only averages, as there are large individual differences as well.

Hormonal Changes

Puberty is the period of rapid growth and sexual development that begins in adolescence and starts at some point between ages 8 and 14. While the sequence of physical changes in puberty is predictable, the onset and pace of puberty vary widely. Every person’s individual timetable for puberty is different and is primarily influenced by genes; however, environmental factors—such as diet and exercise—also exert some influence. Especially for girls, body fat and pubertal timing go together; body fat is linked with the earlier age of puberty.

Puberty involves distinctive physiological changes in an individual’s height, weight, body composition, and circulatory and respiratory systems, and during this time, both the adrenal glands and sex glands mature. These changes are largely influenced by hormonal activity. Many hormones contribute to the beginning of puberty, but most notably, a major rush of estrogen for girls and testosterone for boys. Hormones play an organizational role (priming the body to behave in a certain way once puberty begins) and an activational role (triggering certain behavioral and physical changes). During puberty, the adolescent’s hormonal balance shifts strongly towards an adult state. The hypothalamus triggers the pituitary gland, which secretes a surge of hormonal agents into the bloodstream and initiates a chain reaction.

Puberty occurs over two distinct phases. The first phase, adrenarche, begins at 6 to 8 years of age and involves increased production of adrenal androgens that contribute to a number of pubertal changes, such as skeletal growth. The second phase, gonadarche, begins several years later and involves increased production of hormones governing physical and sexual maturation.

Sexual Maturation

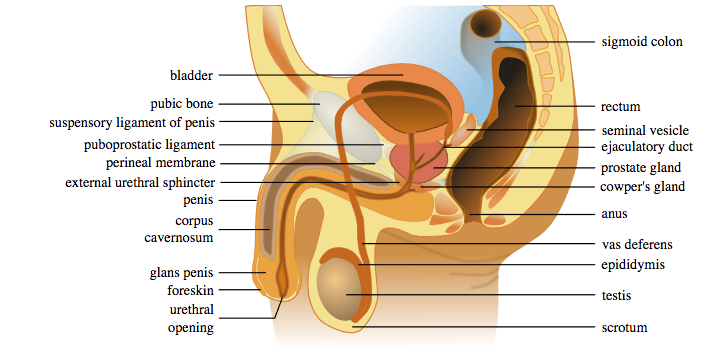

During puberty, primary and secondary sex characteristics develop and mature. Primary sex characteristics are organs specifically needed for reproduction. For males, this includes growth of the testes, penis, scrotum, and spermarche or first ejaculation of semen. This occurs between 11 and 15 years of age. Males produce their sperm in a cycle, and unlike the female’s ovulation cycle, the male sperm production cycle produces millions of sperm daily. The main sex organs for those assigned male at birth are the penis and the testicles, the latter of which produce semen and sperm (see Figure 3). For those assigned female at birth, primary characteristics include growth of the uterus and menarche or the first menstrual period.

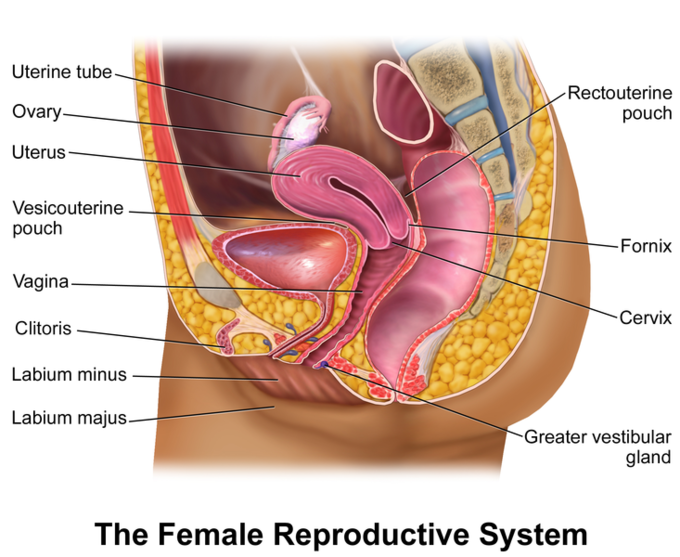

The female gametes, stored in the ovaries, are present at birth but are immature (see Figure 4). Each ovary contains about 400,000 gametes, but only 500 will become mature eggs (Crooks & Baur, 2007). Beginning at puberty, one ovum ripens and is released about every 28 days during the menstrual cycle. Stress and a higher percentage of body fat can cause menstruation at younger ages.

Secondary sex characteristics are physical signs of sexual maturation that do not directly involve sex organs. For those assigned male at birth, this includes broader shoulders and a lower voice as the larynx grows. Hair becomes coarser and darker, and hair growth occurs in the pubic area, under the arms, and on the face (see Figure 1). For those assigned female at birth, breast development occurs around age 10, although full development takes several years. Hips broaden and pubic and underarm hair develops and also becomes darker and coarser (See Figure 2).

The surge of the hormones discussed earlier activates the male and female gonads, putting them into a state of rapid growth and development. The testes primarily release testosterone, and the ovaries release estrogen; the production of these hormones increases gradually until sexual maturation is met.

For girls, observable changes begin with nipple growth and pubic hair. Then, the body increases in height while fat forms, particularly on the breasts and hips. The first menstrual period (menarche) is followed by more growth, which is usually completed by four years after the first menstrual period begins. Girls experience menarche, usually around 12–13 years old. For boys, the usual sequence is the growth of the testes, initial pubic-hair growth, growth of the penis, first ejaculation of seminal fluid (spermarche), appearance of facial hair, a peak growth spurt, deepening of the voice, and final pubic-hair growth (Herman-Giddens et al., 2012). Boys experience spermarche, the first ejaculation, around 13–14 years old.

Acne: An unpleasant consequence of the hormonal changes in puberty is acne, defined as pimples on the skin due to overactive sebaceous (oil-producing) glands (Dolgin, 2011). These glands develop at a greater speed than the skin ducts that discharge the oil. Consequently, the ducts can become blocked with dead skin, and acne will develop. Experiencing acne can lead adolescents to withdraw socially, especially if they are self-conscious about their skin or teased (Goodman, 2006).

Effects of Pubertal Age

The age of puberty is getting younger for children throughout most of the world. According to Euling et al. (2008), data are sufficient to suggest a trend toward an earlier breast development onset and menarche in those with female internal sex organs. A century ago, the average age of someone with female internal sex organs to experience their first period (in the United States and Europe) was 16, while today, it is around 13. Because there is no clear marker of puberty for those with male internal sex organs, it is harder to determine if males assigned at birth are maturing earlier, too. In addition to better nutrition, less positive reasons associated with early puberty for those with internal female sex organs include increased stress, obesity, and endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

Cultural differences are noted with Asian-American females, on average, developing last, while African American females tend to enter puberty the earliest. Hispanic females start puberty the second earliest, while European-American females tend to rank third in their age of starting puberty. Although African American females are typically the first to develop, they are less likely to experience negative consequences of early puberty when compared to European-American females (Weir, 2016). Research has demonstrated mental health problems can be linked to children who begin puberty earlier than their peers. For females, early puberty is associated with depression, substance use, eating disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, and early sexual behavior. (Graber, 2013). Some early-maturing females demonstrate more anxiety and less confidence in their relationships with family and friends, and they compare themselves more negatively to their peers (Weir, 2016).

Additionally, mental health problems are more likely to occur when a child is among the first in their peer group to develop. Because the preadolescent time is one of not wanting to appear different, early-developing children stand out among their peer group and gravitate toward those who are older. For females, this results in them interacting with older peers who engage in risky behaviors such as substance use and early sexual behavior (Weir, 2016). Males also see changes in their emotional functioning at puberty. According to Mendle et al. (2010), while most males experienced a decrease in depressive symptoms during puberty, males who began puberty earlier and exhibited a rapid tempo or a fast rate of change actually increased in depressive symptoms. The researchers concluded that the transition in peer relationships might be especially challenging for males whose pattern of pubertal maturation differs significantly from those of others their age. Consequences for males attaining early puberty was increased odds of cigarette, alcohol, or other drug use (Dudovitz et al., 2015).

Brain and Cognitive Changes

The human brain is not fully developed by the time a person reaches puberty. Between the ages of 10 and 25, the brain undergoes significant changes that have important implications for behavior. The brain reaches 90% of its adult size by the time a person is six or seven years of age. Thus, the brain does not grow in size much during adolescence. However, the creases in the brain continue to become more complex until the late teens. The biggest changes in the folds of the brain during this time occur in the parts of the cortex that process cognitive and emotional information.

During adolescence, myelination and synaptic pruning in the prefrontal cortex increase, improving the efficiency of information processing, and neural connections between the prefrontal cortex and other regions of the brain are strengthened. However, this growth takes time and the growth is uneven. Additionally, changes in both the levels of the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin in the limbic system tend to make adolescents more emotional and more responsive to rewards and stress. In the next section, we will learn about changes in the brain and why teenagers sometimes engage in increased risk-taking behaviors and have varied emotions.

The Teen Brain: 5 Things to Know

As you learn about brain development during adolescence, consider these six facts from The National Institute of Mental Health:

Your brain does not keep getting bigger as you get older

The brain reaches its largest physical size for girls around 11 years old, and for boys around 14. Of course, this difference in age does not mean either boys or girls are smarter than one another!

But that doesn’t mean your brain is done maturing.

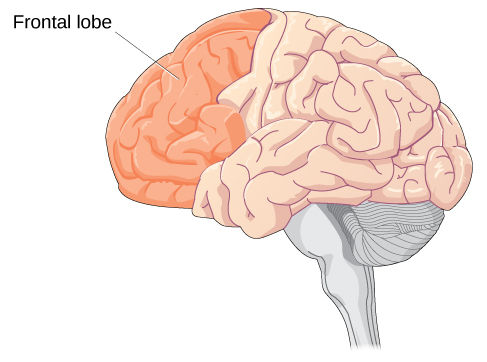

For both boys and girls, although your brain may be as large as it will ever be, your brain doesn’t finish developing and maturing until your mid-to-late-20s. The front part of the brain, called the prefrontal cortex, is one of the last brain regions to mature. It is the area responsible for planning, prioritizing, and controlling impulses.

The teen brain is ready to learn and adapt.

In a digital world that is constantly changing, the adolescent brain is well prepared to adapt to new technology—and is shaped in return by experience.

Many mental disorders appear during adolescence.

All the big changes the brain is experiencing may explain why adolescence is the time when many mental disorders—such as schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and eating disorders—emerge.

The teen brain is resilient.

Although adolescence is a vulnerable time for the brain and for teenagers in general, most teens go on to become healthy adults. Some changes in the brain during this important phase of development actually may help protect against long-term mental disorders.

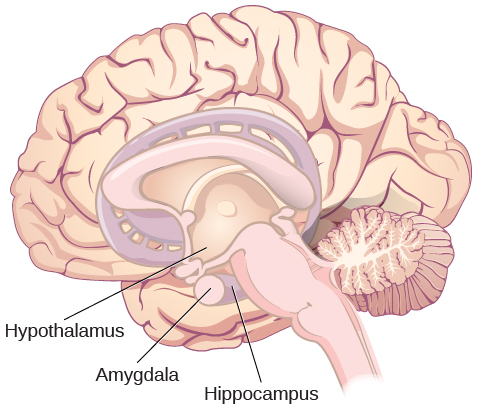

The limbic system develops years ahead of the prefrontal cortex. Development in the limbic system plays an important role in determining rewards and punishments and processing emotional experience and social information. Pubertal hormones target the amygdala directly, and powerful sensations become compelling (Romeo, 2013). Brain scans confirm that cognitive control, revealed by fMRI studies, is not fully developed until adulthood because the prefrontal cortex is limited in connections and engagement (Hartley & Somerville, 2015). Recall that this area is responsible for judgment, impulse control, and planning, and it is still maturing into early adulthood (Casey et al., 2005).

Changes in levels of neurotransmitters (dopamine and serotonin) in the limbic system can make adolescents more emotional and more responsive to rewards and stress compared to when they were younger. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter in the brain associated with pleasure and attuning to the environment during decision-making, while serotonin, the “calming chemical,” eases tension and stress. During adolescence, dopamine levels in the limbic system (see Figure 7) increase, and the input of dopamine to the prefrontal cortex increases. This increased dopamine activity may have implications for adolescent risk-taking and vulnerability to boredom. Serotonin also puts a brake on the excitement and sometimes recklessness that dopamine can produce. If there is a defect in the serotonin processing in the brain, impulsive or violent behavior can result.

When the overall brain chemical system is working well, these chemicals tend to interact to balance out extreme behaviors. However, when stress, arousal, or sensations become extreme, the adolescent brain can be flooded with impulses that overwhelm the prefrontal cortex. As a result, adolescents may engage in increased risk-taking behaviors and emotional outbursts, possibly because the frontal lobes of their brains are still developing. In addition to dopamine, the adolescent brain is affected by oxytocin, which facilitates bonding and makes social connections more rewarding.

The prefrontal cortex is one of the last brain regions to mature (see Figure 8). It is the area responsible for planning, prioritizing, and controlling impulses, and it is still maturing into early adulthood (Casey et al., 2005). Brain scans confirm that cognitive control, revealed by fMRI studies, is not fully developed until adulthood because the prefrontal cortex is limited in connections and engagement (Hartley & Somerville, 2015).

One of the world’s leading experts on adolescent development, Laurence Steinberg, likens this to engaging a powerful engine before the braking system is in place. The result is that many adolescents are more prone to risky behaviors than are children or adults (Steinberg, 2008).

Many changes in the teen brain

In a digital world that is constantly changing, the adolescent brain is well prepared to adapt to new technology—and is shaped in return by experience. All the big changes the brain is experiencing may explain why adolescence is the time when many mental health issues—such as schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and eating disorders—emerge. Although adolescence is a vulnerable time for the brain and for teenagers in general, most teens become healthy adults. Some changes in the brain during this important phase of development actually may help protect against long-term mental health issues.

Although the brain does not get larger during adolescence, it matures and becomes more interconnected and specialized (Giedd, 2015). The myelination and development of connections between neurons continue. This results in an increase in the white matter of the brain and allows adolescents to make significant improvements in their thinking and processing skills. Different brain areas become myelinated at different times. For example, the brain’s language areas undergo myelination during the first 13 years. With greater myelination, however, comes diminished plasticity as a myelin coating inhibits the growth of new connections (Dobbs, 2012). Even as the connections between neurons are strengthened, synaptic pruning occurs more than during childhood as the brain adapts to changes in the environment. Further, the corpus callosum, which connects the two hemispheres, continues to thicken, allowing for stronger connections between brain areas. The hippocampus becomes more strongly connected to the frontal lobes, allowing for greater integration of memory and experiences into our decision-making.

As mentioned in the introduction to adolescence, too many who have read the research on the teenage brain come to quick conclusions about adolescents as irrational loose cannons. However, adolescents are actually making choices influenced by a very different set of chemical influences than their adult counterparts—a hopped-up reward system that can drown out warning signals about risk. Adolescent decisions are not always defined by impulsivity because of lack of brakes but because of planned and enjoyable pressure to the accelerator. It is helpful to put all of these brain processes in a developmental context.

Additionally, the adolescent brain is especially vulnerable to damage from drug exposure. Consequently, adolescents are more sensitive to the effects of repeated marijuana exposure (Weir, 2015). However, researchers have also focused on the highly adaptive qualities of the adolescent brain which allow the adolescent to move away from the family towards the outside world (Dobbs, 2012; Giedd, 2015). Novelty-seeking and risk-taking can generate positive outcomes, including meeting new people and seeking out new situations. Separating from the family and moving into new relationships and different experiences are actually quite adaptive for society.

To learn more, watch this video about adolescent brain research and more about how these changes in brain development also result in behavioral changes.

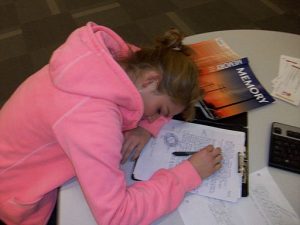

Sleep

According to the National Sleep Foundation (NSF; 2016), to function their best, adolescents need about 8 to 10 hours of sleep each night. The most recent Sleep in America poll in 2006 indicated that adolescents between sixth and twelfth grade were not getting the recommended amount of sleep. On average, adolescents slept only 7 ½ hours per night on school nights, with younger adolescents getting more than older ones (8.4 hours for sixth graders and only 6.9 hours for those in twelfth grade). For older adolescents, only about one in ten (9%) get an optimal amount of sleep, and those who don’t are more likely to experience negative consequences the following day. These include depressed mood, feeling tired or sleepy, being cranky or irritable, falling asleep in school, and drinking caffeinated beverages (NSF, 2016). Additionally, sleep-deprived adolescents are at greater risk for substance abuse, car crashes, poor academic performance, obesity, and a weakened immune system (Weintraub, 2016).

Troxel et al. (2019) found that insufficient sleep in adolescents is also a predictor of risky sexual behaviors. Reasons given for this include that those adolescents who stay out late, typically without parental supervision, are more likely to engage in a variety of risky behaviors, including risky sex, such as not using birth control or using substances before/during sex. An alternative explanation for risky sexual behavior is that the lack of sleep increases impulsivity while negatively affecting decision-making processes.

Why don’t adolescents get adequate sleep? In addition to known environmental and social factors, including work, homework, media, technology, and socializing, the adolescent brain is also a factor. As adolescents go through puberty, their circadian rhythms change and push back their sleep time until later in the evening (Weintraub, 2016). This biological change not only keeps adolescents awake at night, it makes it difficult for them to wake up. When they are awakened too early, their brains do not function optimally. Impairments are noted in attention, academic achievement, and behavior, while increases in tardiness and absenteeism are also seen.

To support adolescents’ later circadian rhythms, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that school begin no earlier than 8:30 a.m. Unfortunately, over 80% of American schools begin their day earlier than 8:30 a.m., with an average start time of 8:03 a.m. (Weintraub, 2016). Psychologists and other professionals have been advocating for later start times based on research demonstrating better student outcomes for later start times. More middle and high schools have changed their start times to better reflect the sleep research. However, the logistics of changing start times and bus schedules are proving too difficult for some schools, leaving many adolescents vulnerable to the negative consequences of sleep deprivation. Troxel et al. (2019) caution that adolescents should find a middle ground between sleeping too little during the school week and too much during the weekends. Keeping consistent sleep schedules of too little sleep will result in sleep deprivation, but oversleeping on weekends can affect the natural biological sleep cycle, making it harder to sleep on weekdays

Link to Learning: School Start Times

As research reveals the importance of sleep for teenagers, many people advocate for later high school start times. Read about some of the research at the National Sleep Foundation on school start times.

California recently enacted later start times. Middle schools cannot start before 8:00 a.m., and high schools cannot start before 8:30 a.m. (Associated Press, 2022). This is an important issue to follow as we learn more from research on implementing these changes.

Health During Adolescence

Nutrition

Adequate adolescent nutrition is necessary for optimal growth and development. Dietary choices and habits established during adolescence greatly influence future health, yet many studies report that teens consume few fruits and vegetables and are not receiving the calcium, iron, vitamins, or minerals necessary for healthy development.

One of the reasons for poor nutrition is anxiety about body image, which is a person’s idea of how his or her body looks. The way adolescents feel about their bodies can affect the way they feel about themselves as a whole. Few adolescents welcome their sudden weight increase, so they may adjust their eating habits to lose weight. Adding to the rapid physical changes, they are simultaneously bombarded by messages, and sometimes teasing, related to body image, appearance, attractiveness, weight, and eating that they encounter in the media, at home, and from their friends/peers (both in-person and via social media).

Much research has been conducted on the psychological ramifications of body image on adolescents. Modern-day teenagers are exposed to more media on a daily basis than any generation before them. Recent studies have indicated that the average teenager watches roughly 1500 hours of television per year, and 70% use social media multiple times a day (Markey, 2019). As such, modern-day adolescents are exposed to many representations of ideal societal beauty. The concept of a person being unhappy with their own image or appearance has been defined as “body dissatisfaction.” In teenagers, body dissatisfaction is often associated with body mass, low self-esteem, and atypical eating patterns. Scholars continue to debate the effects of media on body dissatisfaction in teens. What we do know is that two-thirds of U.S. high school girls are trying to lose weight, and one-third think they are overweight, while only one-sixth are actually overweight (McDow et al., 2019).

Disordered Eating

Disordered eating affects all genders. Dissatisfaction with body image can explain why many teens, mostly girls, eat erratically or ingest diet pills to lose weight and why boys may take steroids to increase their muscle mass. Although eating disorders can occur in children and adults, they frequently appear during the teen years or young adulthood (National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), 2019). Disordered eating affect both genders, although rates among women are 2½ times greater than among men. Similar to women who have eating disorders, some men also have a distorted sense of body image, including muscle dysmorphia or an extreme concern with becoming more muscular.

Risk Factors for Disordered Eating

Because of the high mortality rate, researchers are looking into the etiology of the disorder and associated risk factors. Researchers are finding that eating disorders are caused by a complex interaction of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors (NIMH, 2019). Eating disorders appear to run in families, and researchers are working to identify DNA variations that are linked to the increased risk of developing disordered eating. Researchers have also found differences in patterns of brain activity in women with eating disorders in comparison with healthy women. The main criteria for the most common disordered eating patterns, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder, are described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition, DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). People with anorexia limit food intake, whereas those with bulimia engage in binge and purge cycles: they eat a large amount of food in a short time period and then try to purge those calories to prevent weight gain, often by vomiting or over-exercising. Binge eating disorder was added in 2013 and exhibits the binge cycle without the compensatory purge behavior.

|

Diagnosis |

Major Criteria |

|

Anorexia |

Significantly low body weight, significant weight and shape concerns |

|---|---|

|

Bulimia Nervosa |

Recurrent binge eating and compensatory behaviors (eg, purging, laxative use); significant weight and shape concerns |

|

Binge eating disorder |

Recurrent binge eating; at least 3 of 5 additional criteria related to binge eating (eg, eating large amounts when not physically hungry, eating alone due to embarrassment); significant distress |

Health Consequences of Disordered Eating

For those suffering from anorexia, health consequences include an abnormally slow heart rate and low blood pressure, which increases the risk of heart failure. Additionally, there is a reduction in bone density (osteoporosis), muscle loss and weakness, severe dehydration, fainting, fatigue, and overall weakness. Anorexia nervosa has the highest death rate of any psychiatric disorder. Individuals with this disorder may die from complications associated with starvation, while others die of suicide. In women, suicide is much more common in those with anorexia than with most other mental disorders.

The binging and purging cycle of bulimia can affect the digestive system and lead to electrolyte and chemical imbalances that can affect the heart and other major organs. Frequent vomiting can cause inflammation and possible rupture of the esophagus, as well as tooth decay and staining from stomach acids. Lastly, binge eating disorder results in similar health risks to obesity, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, heart disease, Type II diabetes, and gall bladder disease (National Eating Disorders Association, 2016).

Disordered Eating Treatment

To treat disordered eating, getting adequate nutrition and stopping inappropriate behaviors, such as purging, are the foundations of treatment. Treatment plans are tailored to individual needs and include medical care, nutritional counseling, medications (such as antidepressants), and individual, group, and/or family psychotherapy (NIMH, 2019). For example, the Maudsley Approach has parents of adolescents with anorexia nervosa be actively involved in their child’s treatment, such as assuming responsibility for feeding their child. To eliminate binge eating and purging behaviors, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) assists sufferers by identifying distorted thinking patterns and changing inaccurate beliefs.

Link to Learning

Visit the National Eating Disorders Association to learn more about eating disorders.

Sexual Development

Developing sexually is an expected and natural part of growing into adulthood. Healthy sexual development involves more than sexual behavior. It is the combination of physical, and sexual maturation (puberty, age-appropriate sexual behaviors), the formation of a positive sexual identity, and a sense of sexual well-being (discussed more in-depth later in this module). During adolescence, teens strive to become comfortable with their changing bodies and to make healthy, safe decisions about which sexual activities, if any, they wish to engage in.

Earlier in this section, we discussed primary and secondary sex characteristics. During puberty, every primary sex organ (the ovaries, uterus, penis, and testes) increases dramatically in size and matures in function. During puberty, reproduction becomes possible. Simultaneously, secondary sex characteristics develop. These characteristics are not required for reproduction, but they do signify masculinity and femininity. At birth, boys and girls have similar body shapes, but during puberty, males widen at the shoulders, and females widen at the hips and develop breasts (examples of secondary sex characteristics). Sexual development is impacted by a dynamic mixture of physical and cognitive changes coupled with social expectations. With physical maturation, adolescents may become alternately fascinated with and chagrined by their changing bodies and often compare themselves to the development they notice in their peers or see in the media. For example, many adolescent girls focus on their breast development, hoping their breasts will conform to an ideal body image.

As the sex hormones cause biological changes, they also affect the brain and trigger sexual thoughts. Culture, however, shapes actual sexual behaviors. Emotions regarding sexual experience, like the rest of puberty, are strongly influenced by cultural norms regarding what is expected at what age, with peers being the most influential. Simply put, the most important influence on adolescents’ sexual activity is not their bodies but their close friends, who have more influence than sex or ethnic group norms (van de Bongardt et al., 2015).

Sexual interest and interaction are a natural part of adolescence. Sexual fantasy and masturbation episodes increase between the ages of 10 and 13. Masturbation is very ordinary—even young children have been known to engage in this behavior. As the bodies of children mature, powerful sexual feelings begin to develop, and masturbation helps release sexual tension. For adolescents, masturbation is a common way to explore their erotic potential, and this behavior can continue throughout adult life.

Sexual Interactions

Many early social interactions tend to be nonsexual—text messaging, phone calls, email—but by the age of 12 or 13, some young people may pair off and begin dating and experimenting with kissing, touching, and other physical contact, such as oral sex. The vast majority of young adolescents are not prepared emotionally or physically for oral sex and sexual intercourse. If adolescents this young do have sex, they are highly vulnerable to sexual and emotional abuse, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV, and early pregnancy. For STIs in particular, adolescents are slower to recognize symptoms, tell partners, and get medical treatment, which puts them at risk of infertility and even death.

Adolescents ages 14 to 16 understand the consequences of unprotected sex and teen parenthood if properly taught, but cognitively, they may lack the skills to integrate this knowledge into everyday situations or consistently to act responsibly in the heat of the moment. By the age of 17, many adolescents have willingly experienced sexual intercourse. Teens who have early sexual intercourse report strong peer pressure as a reason behind their decision. Some adolescents are just curious about sex and want to experience it.

Becoming a sexually healthy adult is a developmental task of adolescence that requires integrating psychological, physical, cultural, spiritual, societal, and educational factors. It is particularly important to understand the adolescent in terms of his or her physical, emotional, and cognitive stages. Additionally, healthy adult relationships are more likely to develop when adolescent impulses are not shamed or feared. Guidance is certainly needed, but acknowledging that adolescent sexuality development is both normal and positive would allow for more open communication so adolescents can be more receptive to education concerning the risks (Tolman & McClelland, 2011).

Adolescents are receptive to their culture, to the models they see at home, in school, and in the mass media. These observations influence moral reasoning and moral behavior, which we discuss in more detail later in this module. Decisions regarding sexual behavior are influenced by teens’ ability to think and reason, their values, and their educational experience. Helping adolescents recognize all aspects of sexual development encourages them to make informed and healthy decisions about sexual matters.

Adolescent Pregnancy

In the United States, adolescent pregnancy rates have declined. However, teenage birth rates are higher than in most developed countries. It appears that adolescents in the United States seem to be less sexually active than in previous years, and those who are sexually active seem to be using birth control.

Risk Factors for Adolescent Pregnancy

Miller et al. (2001) found that parent/child closeness, parental supervision, and parents’ values against teen intercourse (or unprotected intercourse) decreased the risk of adolescent pregnancy. In contrast, residing in disorganized/dangerous neighborhoods, living in a lower SES family, living with a single parent, having older sexually active siblings or pregnant/parenting teenage sisters, early puberty, and being a victim of sexual abuse place adolescents at an increased risk of adolescent pregnancy.

Consequences of Adolescent Pregnancy

After a child is born, life can be difficult for teen parents. Fewer than 50% of teenagers who have children before age 18 graduate from high school. Without a high school degree, job prospects tend to be limited, and economic independence can be difficult. Teen parents are more likely to live in poverty, and a majority of unmarried teen mothers receive public assistance within 5 years of the birth of their first child. Further, a child born to a teenage mother is more likely to repeat a grade in school, perform poorly on standardized tests, and drop out before finishing high school when compared to their counterparts who are not born to teen mothers (March of Dimes, 2012). All genders tend to become parents at an older age as their educational attainment increases.

Attributions

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

References

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 74–103). New York, NY: Wiley.

Casey, B. J., Tottenham, N., Liston, C., & Durston, S. (2005). Imaging the developing brain: what have we learned about cognitive development? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(3), 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.01.011

Center for Disease Control. (2016). Birth rates (live births) per 1,000 females aged 15–19 years, by race and Hispanic ethnicity, select years. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/about/birth-rates-chart-2000-2011-text.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2017). The obesity epidemic and United States students. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2017/2017_US_Obesity.pdf

Crooks, K. L., & Baur, K. (2007). Our sexuality (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Dobbs, D. (2012). Beautiful brains. National Geographic, 220(4), 36.

Dolgin, K. G. (2011). The adolescent: Development, relationships, and culture (13th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Dudovitz, R.N., Chung, P.J., Elliott, M.N., Davies, S.L., Tortolero, S,… Baumler, E. (2015). Relationship of Age for Grade and Pubertal Stage to Early Initiation of Substance Use. Preventing Chronic Disease, 12:150234. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.150234.

Euling, S. Y., Herman-Giddens, M.E., Lee, P.A., Selevan, S. G., Juul, A., Sorensen, T. I., Dunkel, L., Himes, J.H., Teilmann, G., & Swan, S.H. (2008). Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics, 121, S172-91. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-1813D.

Eveleth, P. & Tanner, J. (1990). Worldwide variation in human growth (2nd edition). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Giedd, J. N. (2015). The amazing teen brain. Scientific American, 312(6), 32-37.

Goodman, G. (2006). Acne and acne scarring: The case for active and early intervention. Australia Family Physicians, 35, 503- 504.

Graber, J. A. (2013). Pubertal timing and the development of psychopathology in adolescence and beyond. Hormones and Behavior, 64, 262-289.

Hartley, C.A. & Somerville, L.H. (2015). The neuroscience of adolescent decision-making. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 5, 108-115.

Herman-Giddens, M. E., Steffes, J., Harris, D., Slora, E., Hussey, M., Dowshen, S. A., Wasserman, R., Serwint, J. R., Smitherman, L., & Reiter, E. O. (2012). Secondary sexual characteristics in boys: data from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings Network. Pediatrics, 130(5), e1058–e1068. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3291

Kuhn, D. (2013). Reasoning. In. P.D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology. (Vol. 1, pp. 744-764). New York NY: Oxford University Press.

March of Dimes. (2012). Teenage pregnancy. http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/teenage-pregnancy.pdf

Markey, C. H. & Daniels, E. A., (2022). An examination of preadolescent girls’ social media use and body image: Type of engagement may matter most. Body Image, 42, 145 – 149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.05.005.

McDow KB, Nguyen DT, Herrick KA, & Akinbami LJ. (2019). Attempts to lose weight among adolescents aged 16–19 in the United States, 2013–2016. NCHS Data Brief, no 340. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Mendle, J., Harden, K. P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Graber, J. A. (2010). Development’s tortoise and hare: Pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology, 46,1341–1353. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020205

Miller, B. C., Benson, B., & Galbraith, K. A. (2001). Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: A research synthesis. Developmental Review: DR, 21(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.2000.0513

National Eating Disorders Association. (2016). Health consequences of eating disorders. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/health-consequences-eating-disorders

National Institutes of Mental Health. (2021). Eating Disorders. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders/index.shtml

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). (2020). The teen brain: 7 things to know. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/the-teen-brain-7-things-to-know

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). I’m so stressed out! Fact sheet. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/so-stressed-out-fact-sheet

National Sleep Foundation. (2016). Teens and sleep. Retrieved from https://sleepfoundation.org/sleep topics/teens-and-sleep

Romeo, R.D. (2013). The teenage brain: The stress response and the adolescent brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(2), 140-145.

Seifert, K. (2012). Educational Psychology. http://cnx.org/content/col11302/1.2

Steinberg, L. (2008) A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review, 28:78-106.

Steinberg, L., Icenogle, G., Shulman, E.P., et al. (2018). Around the world, adolescence is a time of heightened sensation-seeking and immature self-regulation. Developmental Science, 21, e12532.

Tartamella, L., Herscher, E., Woolston, C. (2004). Generation extra large: Rescuing our children from the obesity epidemic. New York: Basic Books.

Tolman, D., & McClelland, S. I. (2011). Normative sexuality development in adolescence: A decade in review, 2000–2009. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00726.x

van de Bongardt, D., Reitz, E., Sandfort, T., & Deković, M. (2015). A meta-analysis of the relations between three types of peer norms and adolescent sexual behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19(3), 203–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314544223

Weintraub, K. (2016). Young and sleep deprived. Monitor on Psychology, 47(2), 46-50.

Weir, K. (2015). Marijuana and the developing brain. Monitor on Psychology, 46(10), 49-52.

Weir, K. (2016). The risks of earlier puberty. Monitor on Psychology, 47(3), 41-44.