Section 3: Genetics and Prenatal Development

3.2 Prenatal Development

What happens during prenatal development and pregnancy?

How did you come to be who you are? From beginning as a one-cell structure to your birth, your prenatal development occurs in an orderly and delicate sequence. There are three stages of prenatal development: germinal, embryonic, and fetal. Keep in mind that this is different than the three trimesters of pregnancy. Let’s take a look at what happens to the developing baby in each of these stages.

How did you come to be who you are? From beginning as a one-cell structure to your birth, your prenatal development occurs in an orderly and delicate sequence. There are three stages of prenatal development: germinal, embryonic, and fetal. Keep in mind that this is different than the three trimesters of pregnancy. Let’s take a look at what happens to the developing baby in each of these stages.

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between development during the germinal, embryonic, and fetal periods

- Define teratogens and describe the factors that influence their effects

- Examine risks to prenatal development posed by exposure to teratogens

- List and describe the effects of several common teratogens

- Explain maternal and paternal factors that affect the developing fetus

- Explain the types of prenatal assessment

- Explain potential complications of pregnancy and delivery

- Identify the impact of systemic racism on pregnancy and birth outcomes.

Prenatal Development

“The body of the unborn baby is more complex than ours. The preborn baby has several extra parts to his body which he needs only so long as he lives inside his mother. He has his own space capsule, the amniotic sac. He has his own lifeline, the umbilical cord, and he has his own root system, the placenta. These all belong to the baby himself, not to his mother. They are all developed from his original cell.”

Now, we turn our attention to the three periods of prenatal development: the germinal period, the embryonic period, and the fetal period. While medical practitioners refer to trimesters, the three periods of prenatal development are stage-based and are not equally distributed as 13 weeks each. Here is an overview of some of the changes that take place during each period.

The Germinal Period (Weeks 0-3)

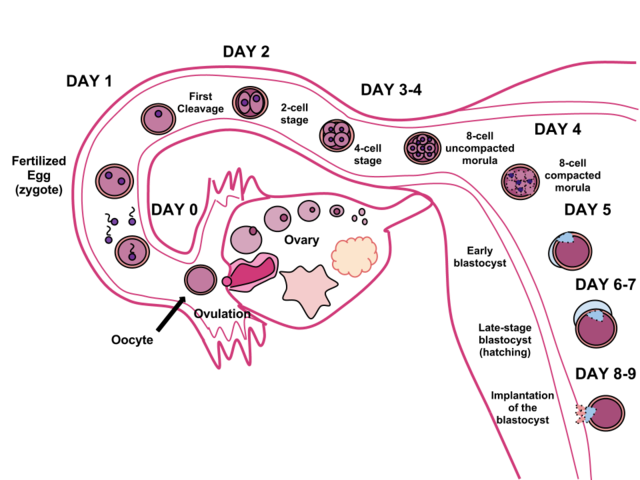

The germinal period begins from conception to the implementation of the zygote in the lining of the uterus, which lasts about 14 days. At ejaculation, a multitude of sperm are released into the vagina, and it only takes one sperm to fertilize the egg/ovum (Figure 1). When the egg ripens, it is released from the ovaries into the fallopian tube, which travels down to the uterus within 3-4 days, where fertilization happens.

Immediately after the single sperm penetrates through the egg’s wall, the egg becomes hard and blocks other sperm from entering it. Only the sperm head, which carries genetic information from the male, can fuse with the nucleus of the egg. From there, a new cell forms, also known as a zygote, which contains genetic information from the male and female. During this time, the organism begins cell division and growth. After the fourth doubling, differentiation of the cells begins to occur as well. It is estimated that about 60 percent of natural conceptions fail to implant in the uterus. The rate is higher for in vitro conceptions.

Throughout this process, the organism begins cell division through mitosis. After five days of mitosis, there are 100 cells, which is now called a blastocyst. The blastocyst consists of both an inner and an outer group of cells. The inner group of cells (or embryonic disk) will become the embryo, while the outer group of cells, or trophoblast, becomes the support system, which nourishes the developing organism. Other cells develop to form the amniotic sac. The amniotic sac fills with a clear liquid (amniotic fluid) and expands to envelop the developing embryo, which floats within it. This stage ends when the blastocyst fully implants into the uterine wall (United States National Library of Medicine, 2015).

Less than one-half of all zygotes survive beyond the first two weeks (Hall, 2004). One reason for this is outcome is that the egg and sperm do not join properly. As a result, their genetic material does not combine, there is too little or damaged genetic material, the zygote does not replicate, or the blastocyst does not implant into the uterine wall. The figure (2) above illustrates the journey of the ova from its release to its fertilization, cell duplication, and implantation into the uterine lining.

In Vitro Fertilization

IVF, which stands for in vitro fertilization, is an assisted reproductive technology. In vitro, which in Latin translates to “in glass,” refers to a procedure that takes place outside of the body. There are many different indications for IVF. For example, someone may produce normal eggs, but the eggs cannot reach the uterus because the uterine tubes are blocked or otherwise compromised. There are also challenges with low sperm count, low sperm motility, sperm with an unusually high percentage of morphological abnormalities, or sperm that are incapable of penetrating the zona pellucida of an egg.

A typical IVF procedure begins with egg collection. A normal ovulation cycle produces only one oocyte, but the number can be boosted significantly (to 10–20 oocytes) by administering a short course of gonadotropins. The course begins with follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) analogs, which support the development of multiple follicles and ends with a luteinizing hormone (LH) analog that triggers ovulation. Right before the ova are released from the ovary, they are harvested using ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval. In this procedure, ultrasound allows a physician to visualize mature follicles. The ova are aspirated (sucked out) using a syringe.

In parallel, sperm are obtained from a partner or from a donor/sperm bank. The sperm is prepared by washing to remove seminal fluid because seminal fluid contains a peptide, FPP (or fertilization promoting peptide), that—in high concentrations—prevents capacitation of the sperm. The sperm sample is also concentrated to increase the sperm count per milliliter.

Next, the eggs and sperm are mixed in a petri dish. The ideal ratio is 75,000 sperm to one egg. If there are severe problems with the sperm—for example, the count is exceedingly low, or the sperm are completely nonmotile or incapable of binding to or penetrating the zona pellucida—a sperm can be injected into an egg. This is called intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

The embryos are then incubated until they either reach the eight-cell stage or the blastocyst stage. In the United States, fertilized eggs are typically cultured to the blastocyst stage because this results in a higher pregnancy rate. Finally, the embryos are transferred to the uterus using a plastic catheter (tube).

IVF is a relatively new and still evolving technology. Until recently, it was necessary to transfer multiple embryos to achieve a good chance of a pregnancy. Today, however, transferred embryos are much more likely to implant successfully, so countries that regulate the IVF industry cap the number of embryos that can be transferred per cycle at two. This reduces the risk of multiple-birth pregnancies.

Watch this video on prenatal development:

It explains many of the developmental milestones and changes that happen during each month of development for the embryo and fetus.

The Embryonic Period (Weeks 3-8)

The embryonic period begins once the zygote is implanted in the uterine wall and lasts from the third through the eighth week after conception. Upon implantation, this multi-cellular organism is called an embryo (Figure 3). Blood vessels grow, forming the placenta, a structure connected to the uterus that provides nourishment and oxygen from the mother to the developing embryo via the umbilical cord.

During this period, cells continue to differentiate. Basic structures of the embryo start to develop into areas that will become the head, chest, and abdomen. During the embryonic stage, the heart begins to beat and organs form and begin to function. At 22 days after conception, the neural tube forms along the back of the embryo, developing into the spinal cord and brain.

Growth during prenatal development occurs in two major directions: from head to tail (cephalocaudal development) and from the midline outward (proximodistal development). This means that those structures nearest the head develop before those nearest the feet, and those structures nearest the torso develop before those away from the center of the body (such as hands and fingers).

The head develops in the fourth week, and the precursor to the heart begins to pulse. In the early stages of the embryonic period, gills and a tail are apparent. But by the end of this stage, they disappear, and the organism takes on a more human appearance. At the end of this period, the embryo is approximately 1 inch in length and weighs about 4 grams. The embryo can move and respond to touch at this time.

About 20 percent of organisms fail during the embryonic period, usually due to gross chromosomal abnormalities. As in the case of the germinal period, often the mother does not yet know that she is pregnant. It is during this stage that the major structures of the body are taking form making the embryonic period the time when the organism is most vulnerable to the greatest amount of damage if exposed to harmful substances. Potential mothers are not often aware of the risks they introduce to the developing child during this time.

The Fetal Period (Weeks 9-40)

When the organism is about nine weeks old, the embryo is called a fetus. At this stage, the fetus is about the size of a kidney bean and begins to take on the recognizable form of a human being as the “tail” begins to disappear (Figure 4).

The sex organs begin to differentiate from 9 to 12 weeks. By the 12th week, the fetus has all its body parts, including external genitalia. In the following weeks, the fetus will develop hair, nails, and teeth, and the excretory and digestive systems will continue to develop. At the end of the 12th week, the fetus is about 3 inches long and weighs about 28 grams.

At about 16 weeks, the fetus is approximately 4.5 inches long. Fingers and toes are fully developed, and fingerprints are visible. During the 4-6 months, the eyes become more sensitive to light, and hearing develops. The respiratory system continues to develop. Reflexes such as sucking, swallowing, and hiccupping develop during the 5th month. Cycles of sleep and wakefulness are present at that time as well. Throughout the fetal stage, the brain continues to grow and develop, nearly doubling in size from weeks 16 to 28. The majority of the neurons in the brain have developed by 24 weeks, although they are still rudimentary, and the glial or nurse cells that support neurons continue to grow. At 24 weeks, the fetus can feel pain (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 1997).

The first chance of survival outside the womb, known as the age of viability, is reached at about 22 to 26 weeks (Moore & Persaud, 1998). Before we are born (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders.[/footnote] By the time the fetus reaches the sixth month of development (24 weeks), it weighs up to 1.4 pounds. Hearing develops so the fetus can respond to sounds. The internal organs, such as the lungs, heart, stomach, and intestines, have formed enough that a fetus born prematurely at this point has a chance to survive outside of the mother’s womb.

Between the seventh and ninth months, the fetus is primarily preparing for birth. It is exercising its muscles, and its lungs begin to expand and contract. It is developing fat layers under the skin. The fetus gains about 5 pounds and 7 inches during this last trimester of pregnancy, including a layer of fat gained during the eighth month. This layer of fat serves as insulation and helps the baby regulate body temperature after birth.

Around 36 weeks, the fetus is almost ready for birth. It weighs about 6 pounds and is about 18.5 inches long. By week 37, all of the fetus’s organ systems are developed enough that it could survive outside the uterus without many of the risks associated with premature birth. The fetus continues to gain weight and grow in length until approximately 40 weeks. By then, the fetus has very little room to move around, and birth becomes imminent (Figure 5).

Prenatal Brain Development

Prenatal brain development begins in the third gestational week with the differentiation of stem cells, which are capable of producing all the different cells that make up the brain (Stiles & Jernigan, 2010). The location of these stem cells in the embryo is referred to as the neural plate. By the end of the third week, two ridges appear along the neural plate, first forming the neural groove and then the neural tube. The open region in the center of the neural tube forms the brain’s ventricles and spinal canal. By the end of the embryonic period, or week eight, the neural tube has further differentiated into the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain.

Brain development during the fetal period involves neuron production, migration, and differentiation. From the early fetal period until midgestation, most of the 85 billion neurons have been generated, and many have already migrated to their brain positions. Neurogenesis, or the formation of neurons, is largely completed after five months of gestation. One exception is in the hippocampus, which continues to develop neurons throughout life. Neurons that form the neocortex, or the layer of cells that lie on the surface of the brain, migrate to their location in an orderly way. Neural migration is mostly completed by the 29th week. Once in position neurons begin to produce dendrites and axons that begin to form the neural networks responsible for information processing. Regions of the brain that contain the cell bodies are referred to as gray matter because they look gray in appearance. The axons that form the neural pathways make up the white matter because they are covered in myelin, a fatty substance that is white in appearance. Myelin aids in both the insulation and efficiency of neural transmission. Although cell differentiation is complete at birth, the growth of dendrites, axons, and synapses continues for years.

Environmental Risks

Teratology

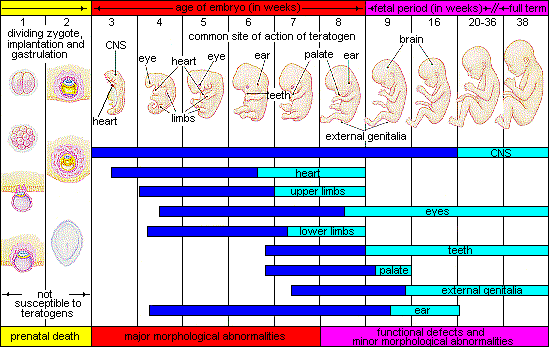

Quality prenatal care is essential. The developing embryo and fetus are most at risk for some of the most severe problems during the first three months of development. Unfortunately, most females are unaware that they are pregnant at this time. It is estimated that 10% of all birth defects are caused by prenatal exposure or teratogen. Teratogens are factors that can contribute to birth defects, which include some maternal diseases, drugs, alcohol, and stress. These exposures can also include environmental and occupational exposures. Today, we know many of the factors that can jeopardize the health of the developing child. Teratogen-caused birth defects are potentially preventable. The study of factors that contribute to birth defects is called teratology.

Teratogens are usually discovered after an increased prevalence of a particular birth defect. For example, in the early 1960s, a drug known as thalidomide was used to treat morning sickness. Exposure of the fetus during this early stage of development resulted in cases of phocomelia, a congenital malformation in which the hands and feet are attached to abbreviated arms and legs.

Factors Influencing Prenatal Risks

There are several considerations in determining the type and amount of damage that might result from exposure to a particular teratogen (Berger, 2005). These include:

- The timing of the exposure: Structures in the body are vulnerable to the most severe damage when they are forming. If a substance is introduced during a particular structure’s critical period (time of development), the damage to that structure may be more significant. For example, the ears and arms reach their critical periods at about six weeks after conception. If a woman exposes the embryo to certain substances during this period, the arms and ears may be malformed.

- The amount of exposure: Some substances are not harmful unless the amounts reach a certain level. The critical level depends in part on the size and metabolism of the mother.

- Dose-response relation: The higher the exposure to the potential teratogen, the more likely it is that the fetus will suffer damage, and the more severe the damage is likely to be with greater exposure.

- Genetics: Genetic makeup also influences the impact a particular teratogen might have on the child. Fraternal twin studies that have been conducted in the same prenatal environment yet have not experienced the same teratogenic effects suggest this. The genetic makeup of the mother can also have an effect; some mothers may be more resistant to teratogenic effects than others.

- Biological sex: Males are more likely to experience damage due to teratogens than females. The Y chromosome, which contains fewer genes than the X, may have an impact.

Figure 6 illustrates the timing of teratogen exposure and the types of structural defects that can occur during the prenatal period.

A Look at Some Teratogens

Alcohol

One of the most commonly used teratogens is alcohol. Because half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, it is recommended that women of child-bearing age take great caution against drinking alcohol when not using birth control and when pregnant (Surgeon General’s Advisory on Alcohol Use During Pregnancy, 2005). Alcohol consumption, particularly during the second month of prenatal development but at any point during pregnancy, may lead to neurocognitive and behavioral difficulties that can last a lifetime.

There is no acceptable safe limit for alcohol use during pregnancy, but binge drinking (5 or more drinks on a single occasion) or having 7 or more drinks during a single week places a child at particularly high risk. In extreme cases, alcohol consumption can lead to fetal death, but more frequently, it can result in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). This terminology is now used when looking at the effects of exposure and replaces the term fetal alcohol syndrome. It is preferred because it recognizes that symptoms occur on a spectrum and that all individuals do not have the same characteristics. Children with FASD share certain physical features such as flattened noses, small eye openings, small heads, intellectual developmental delays, and behavioral problems. Those with FASD are more at risk for lifelong problems such as criminal behavior, psychiatric problems, and unemployment (CDC, 2006).

The terms alcohol-related neurological disorder (ARND) and alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD) have replaced the term Fetal Alcohol Effects to refer to those with less extreme symptoms of FASD. ARBD includes kidney, bone, and heart problems.

Malnutrition

Pregnant women who are not getting enough calories and important micro-nutrients are at increased risk for having low birth weight babies (under 2,500 grams or 5 1/2 pounds) and other complications. One vital nutrient is folic acid, found in leafy green vegetables, legumes, egg yolk, liver, and citrus fruit (Greenberg et al., 2011). Folic acid deficiency during pregnancy is associated with neural tube disorders, like spina bifida, where the end of the spine does not close) and anencephaly, when the brain does not fully develop. Some common genetic variations reduce how women metabolize folic acid, which is why women of reproductive age are recommended to take 400 micrograms of folic acid each day (US Preventive Services Task Force, 2017).

Tobacco

Smoking is also considered a teratogen because nicotine travels through the placenta to the fetus. When the mother smokes, the developing baby experiences a reduction in blood oxygen levels. Tobacco use during pregnancy has been associated with low birth weight, placenta previa, birth defects, preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, and sudden infant death syndrome. Smoking in the month before getting pregnant and throughout pregnancy increases the chances of these risks. Quitting smoking before getting pregnant is best. However, for women who are already pregnant, quitting as early as possible can still help protect against some health problems for the mother and baby.

Another widely used teratogen is tobacco; in fact 2016, more than 7% of pregnant women smoked in 2016 (Someji & Beltrán-Sánchez, 2019). According to Tong et al. (2013), in conjunction with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, data from 27 sites in 2010 representing 52% of live births, showed that among women with recent live births:

- About 23% reported smoking in the 3 months prior to pregnancy.

- Almost 11% reported smoking during pregnancy.

- More than half (54.3%) reported that they quit smoking by the last 3 months of pregnancy.

- Almost 16% reported smoking after delivery.

When comparing the ages of women who smoked:

- Women <20, 13.6% smoked during pregnancy

- Women 20–24 ,17.6% smoked during pregnancy

- Women 25–34 , 8.8% smoked during pregnancy

- Women ≥35, 5.7% smoked during pregnancy

The findings among racial and ethnic groups indicated that smoking during pregnancy was highest among American Indians/Alaska Natives (26.0%) and lowest among Asians/Pacific Islanders (2.1%).

When a pregnant person smokes, the fetus is exposed to dangerous chemicals including nicotine, carbon monoxide, and tar, which lessen the amount of oxygen available to the fetus. Oxygen is important for overall growth and development. Tobacco use during pregnancy has been associated with ecotopic pregnancy (fertilized egg implants itself outside of the uterus), placenta previa (placenta lies low in the uterus and covers all or part of the cervix), placenta abruption (placenta separates prematurely from the uterine wall), preterm delivery, low birth weight, stillbirth, fetal growth restriction, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), birth defects, learning disabilities, and early puberty in girls (Center for Disease Control, 2015d).

When gestational parents are exposed to secondhand smoke during pregnancy, this also increases the risk of low-birth-weight infants. In addition, exposure to thirdhand smoke, or toxins from tobacco smoke that linger on clothing, furniture, and in locations where smoking has occurred, can have a negative impact on infants’ lung development. Rehan et al., (2011) found that prenatal exposure to thirdhand smoke played a greater role in altered lung functioning than postnatal exposure.

Drugs

Prescription/Over-the-counter Drugs: About 70% of pregnant people take at least one prescription drug (March of Dimes, 2016e). A person should not be taking any prescription medication during pregnancy unless it was prescribed by a health care provider who knows that person is pregnant. Some prescription drugs can cause birth defects, problems in overall health, and development of the fetus. Over-the-counter drugs are also a concern during the prenatal period because they may cause certain health problems. For example, the pain reliever ibuprofen can cause serious blood flow problems to the fetus during the last three months.

Illicit Drugs: Common illicit drugs include marijuana, cocaine, ecstasy and other club drugs, heroin, and prescription drugs that are abused. It is difficult to fully determine the effects of particular illicit drugs on a developing fetus because most mothers who use, use more than one substance and have other unhealthy behaviors. These include smoking, drinking alcohol, not eating healthy meals, and being more likely to get a sexually transmitted disease.

However, several problems seem clear. The use of cocaine is connected with low birth weight, stillbirths, and spontaneous abortion. Heavy marijuana use is associated with problems in brain development (March of Dimes, 2016c). If a baby’s gestational parent used an addictive drug during pregnancy, that baby can get addicted to the drug before birth and go through drug withdrawal after birth, also known as Neonatal abstinence syndrome (March of Dimes, 2015d). Other complications of illicit drug use include premature birth, smaller-than-normal head size, birth defects, heart defects, and infections. Additionally, babies born to gestational parents who use drugs may have problems later in life, including death from sudden infant death syndrome, slower than normal growth, and learning and behavior difficulties. Children of substance-abusing parents are also considered at high risk for a range of biological, developmental, academic, and behavioral problems, including developing substance abuse problems of their own (Conners et al., 2003).

Environmental Chemicals

Pollutants. More than 83,000 chemicals are used in the United States, and little information is available on their effects on unborn children (March of Dimes, 2016b).

- Lead poisoning. An environmental pollutant of significant concern is lead, which has been linked to fertility problems, high blood pressure, low birth weight, prematurity, miscarriage, and delayed neurological development. Grossman and Slutsky (2017) found that babies born in Flint, Michigan, an area identified with high lead levels in the drinking water, were premature, weighed less than average, and gained less weight than normal.

- Pesticides. Chemicals in certain pesticides are also potentially damaging and may lead to miscarriage, low birth weight, premature birth, birth defects, and learning problems (March of Dimes, 2014).

- Bisphenol A. Prenatal exposure to bisphenol A (BPA), a chemical commonly used in plastics and food and beverage containers, may disrupt the action of certain genes contributing to particular birth defects (March of Dimes, 2016b).

- Radiation. If a gestational parent is exposed to radiation, it can get into the bloodstream and pass through the umbilical cord to the fetus. Radiation can also build up in body areas close to the uterus, such as the bladder. Exposure to radiation can result in miscarriage, affect brain development, slow the baby’s growth, or cause birth defects or cancer.

- Mercury. Mercury, a heavy metal, can cause brain damage and affect the baby’s hearing and vision. This is why people are cautioned about the amount and type of fish they consume during pregnancy.

Toxoplasmosis. The tiny parasite, toxoplasma gondii, causes an infection called toxoplasmosis. According to the March of Dimes (2012d), toxoplasma gondii infects more than 60 million people in the United States. A healthy immune system can keep the parasite at bay, resulting in no symptoms, so most people do not know they are infected. As a routine prenatal screening frequently does not test for the presence of this parasite, pregnant people may want to talk to their health-care provider about being tested. Toxoplasmosis can cause premature birth and stillbirth and can result in birth defects to the eyes and brain. While most babies born with this infection show no symptoms, ten percent may experience eye infections, enlarged liver and spleen, jaundice, and pneumonia. To avoid being infected, gestational parents should avoid eating undercooked or raw meat and unwashed fruits and vegetables, touching cooking utensils that touch raw meat or unwashed fruits and vegetables, and touching cat feces, soil, or sand. If people think they may have been infected during pregnancy, they should have their newborn tested.

Environmental chemicals can include exposure to a wide array of agents, including pollution, organic mercury compounds, herbicides, and industrial solvents. Some environmental pollutants of major concern include lead poisoning, which is connected with low birth weight and slowed neurological development. Children who live in older housing in which lead-based paints have been used have been known to eat peeling paint chips thus being exposed to lead. The chemicals in certain herbicides are also potentially damaging. Radiation is another environmental hazard that a pregnant woman must be aware of. If a mother is exposed to radiation, particularly during the first three months of pregnancy, the child may suffer some congenital deformities. There is also an increased risk of miscarriage and stillbirth. Mercury leads to physical deformities and intellectual disabilities (Dietrich, 1999).

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Gonorrhea, syphilis, and chlamydia are sexually transmitted infections that can be passed to the fetus by an infected gestational parent. Gestational parents should be tested as early as possible to minimize the risk of spreading these infections to their unborn children. Additionally, the earlier the treatment begins, the better the health outcomes for parents and babies (CDC, 2016d). Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) can cause ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, premature rupture of the amniotic sac, premature birth, and stillbirths. and birth defects (March of Dimes, 2013). Although some STDs can cross the placenta and infect the developing fetus, most babies become infected with STDS while passing through the birth canal during delivery.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). One of the most potentially devastating teratogens is HIV. HIV and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) are leading causes of illness and death in the United States (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2015). One of the main ways children under age 13 become infected with HIV is via mother-to-child transmission of the virus prenatally, during labor, or by breastfeeding (CDC, 2016c). There are measures that can be taken to lower the chance the child will contract the disease. HIV positive gestational parents who take antiviral medications during their pregnancy greatly reduce the chance of passing the virus to the fetus. The risk of transmission is less than 2%; in contrast, if the gestational parent does not take antiretroviral drugs, the risk is elevated to 25% (CDC, 2016b). However, the long-term risks of prenatal exposure to the medication are not known. It is recommended that people with HIV deliver the child by c-section and that after birth, they avoid breastfeeding.

WHAT DO YOU THINK? Should Women Who Use Drugs During Pregnancy Be Arrested and Jailed?

As you now know, women who use drugs or alcohol during pregnancy can cause serious lifelong harm to their children. Some people have advocated mandatory screenings for women who are pregnant and have a history of drug abuse, and if the women continue using, to arrest, prosecute, and incarcerate them (Figdor & Kaeser, 1998). This policy was tried in Charleston, South Carolina, as recently as 20 years ago. The policy was called the Interagency Policy on Management of Substance Abuse During Pregnancy and had disastrous results.

The Interagency Policy applied to patients attending the obstetrics clinic at MUSC, which primarily serves patients who are indigent or on Medicaid. It did not apply to private obstetrical patients. The policy required patient education about the harmful effects of substance abuse during pregnancy. . . . [A] statement also warned patients that protection of unborn and newborn children from the harms of illegal drug abuse could involve the Charleston police, the Solicitor of the Ninth Judicial Court, and the Protective Services Division of the Department of Social Services (DSS). (Jos, Marshall, & Perlmutter, 1995, pp. 120–121)

This policy seemed to deter women from seeking prenatal care, deterred them from seeking other social services, and was applied solely to low-income women, resulting in lawsuits. The program was canceled after 5 years, during which 42 women were arrested. A federal agency later determined that the program involved human experimentation without the approval and oversight of an institutional review board (IRB).

In July 2014, Tennessee enacted a law that allows people who illegally use a narcotic drug while pregnant to be prosecuted for assault if their infant is harmed or addicted to the drug (National Public Radio, 2015). According to the National Public Radio report, a baby is born dependent on a drug every 30 minutes in Tennessee, which is a rate three times higher than the national average. However, since the law took effect, the number of babies born having drug withdrawal symptoms has not diminished. Critics contend that the criminal justice system should not be involved in what is considered a healthcare problem.

What do you think? Do you consider the issue of gestational parents using illicit drugs more of a legal or medical concern? What were the flaws in the program, and how would you correct them? What are the ethical implications of charging pregnant women with child abuse?

Maternal and Paternal Factors

Several factors can impact pregnancy and birth outcomes, such as paternal and maternal age, environmental teratogens, and the health conditions of both the male and female.

Paternal Age

The age of fathers at the time of conception is also an important factor in health risks for children. According to Nippoldt (2015), the offspring of men over 40 face an increased risk of miscarriage, autism, birth defects, achondroplasia (bone growth disorder), and schizophrenia. These increased health risks are thought to be due to chromosomal aberrations and mutations that accumulate during the maturation of sperm cells in older men (Bray, Gunnell, & Smith, 2006). However, like older women, the overall risks are small.

In addition, men are more likely than women to work in occupations where hazardous chemicals, many of which have teratogenic effects or may cause genetic mutations, are used (Cordier, 2008). These may include petrochemicals, lead, and pesticides that can cause abnormal sperm and lead to miscarriages or diseases. Men are also more likely to be a source of secondhand smoke for their developing offspring. As noted earlier, smoking by either the mother or around the mother can impede prenatal development.

Maternal age

Women who become pregnant at 35 years or older generally have healthy pregnancies. However, according to March of Dimes (2016), women older than 35 years of age are at greater risk of:

- Fertility problems

- High blood pressure

- Diabetes

- Miscarriages

- Placenta previa

- Cesarean section

- Premature birth

- Stillbirth

- A baby with a genetic disorder or other birth defects

Exposure to environmental teratogens can affect the quality of eggs as women age and the quality of sperm from males. Women’s reproductive systems naturally age with time, which can have a significant negative impact on pregnancy, although a woman is born with all her eggs. For this reason, some women older than 35 choose special prenatal screening, such as blood screening, to determine if there are any health risks for the baby.

Women who delay having children may live longer. Sun et al. (2015) found that women who had their last child after the age of 33 doubled their chances of living to age 95 or older compared to women who had their last child before their 30th birthday. A woman’s natural ability to have a child at a later age indicates that her reproductive system is aging slowly, and consequently, so is the rest of her body.

Because gestational parents are born with all their eggs, environmental teratogens can affect the quality of the eggs as they age. Also, their reproductive system ages, which can adversely affect the pregnancy. Some people over 35 choose special prenatal screening tests, such as a maternal blood screening, to determine if there are any health risks for the baby.

Although there are medical concerns associated with having a child later in life, there are also many positive consequences to being a more mature parent. Older parents are more confident, less stressed, and typically married, which can provide family stability. Their children perform better on math and reading tests, and they are less prone to injuries or emotional troubles (Albert, 2013). People who choose to wait are often well-educated and lead healthy lives. According to Gregory (2007), older women are more stable, demonstrate a stronger family focus, possess greater self-confidence, and have more money. Having a child later in one’s career equals overall higher wages. In fact, for every year gestational parents delay becoming a parent, they make 9% more in lifetime earnings. Lastly, gestational parents who delay having children actually live longer. Sun et al. (2015) found that women who had their last child after the age of 33 doubled their chances of living to age 95 or older than women who had their last child before their 30th birthday. A gestational parent’s natural ability to have a child at a later age indicates that their reproductive system is aging slowly, and consequently, so is the rest of their body.

Teenage pregnancy

A teenage gestational parent is at a greater risk for complications during pregnancy, including anemia and high blood pressure. These risks are even greater for those under age 15. Infants born to teenage gestational parents have a higher risk of being born prematurely and having low birth weight or other serious health problems. Premature and low birth weight babies may have organs that are not fully developed, which can result in breathing problems, bleeding in the brain, vision loss, and serious intestinal problems. Very low birthweight babies (less than 3 1/3 pounds) are more than 100 times as likely to die, and moderately low birthweight babies (between 3 1/3 and 5 ½ pounds) are more than 5 times as likely to die in their first year, than normal weight babies (March of Dimes, 2012c).

Again, the risk is highest for babies of gestational parents under age 15. A primary reason for these health issues is that teenagers are the least likely of all age groups to get early and regular prenatal care. Additionally, they may engage in risky behaviors during pregnancy, including eating unhealthy food, smoking, drinking alcohol, and taking drugs. Additional concerns for teenagers are repeat births. About 25% of teen gestational parents under age 18 have a second baby within 2 years after the first baby’s birth.

Gestational diabetes

Seven percent of pregnant people develop gestational diabetes (March of Dimes, 2015b). Diabetes is a condition where the body has too much glucose in the bloodstream. Most pregnant people have their glucose level tested at 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy. Gestational diabetes usually goes away after the gestational parent gives birth, but it might indicate a risk for developing diabetes later in life. If untreated, gestational diabetes can cause premature birth, stillbirth, infant breathing problems at birth, jaundice, or low blood sugar. Babies born to mothers with gestational diabetes can also be considerably heavier (more than 9 pounds), making the labor and birth process more difficult. For expectant mothers, untreated gestational diabetes can cause preeclampsia (high blood pressure and signs that the liver and kidneys may not be working properly) discussed later in the chapter.

Risk factors for gestational diabetes include age (being over age 25), being overweight or gaining too much weight during pregnancy, a family history of diabetes, having had gestational diabetes with a prior pregnancy, and race and ethnicity (mothers who are African-American, Native American, Hispanic, Asian, or Pacific Islander have a higher risk). Eating healthy food and maintaining a healthy weight during pregnancy can reduce the chance of gestational diabetes. People who already have diabetes and become pregnant need to attend all their prenatal care visits and follow the same advice as those for people with gestational diabetes, as the risk of preeclampsia, premature birth, birth defects, and stillbirth are the same.

High blood pressure (Hypertension)

Hypertension is a condition in which the pressure against the wall of the arteries becomes too high. There are two types of high blood pressure during pregnancy, gestational and chronic. Gestational hypertension only occurs during pregnancy and goes away after birth. Chronic high blood pressure refers to people who already had hypertension before the pregnancy or to those who developed it during pregnancy, and it continued after birth. According to the March of Dimes (2015c), about 8 in every 100 pregnant people have high blood pressure. High blood pressure during pregnancy can cause premature birth and low birth weight (under five and a half pounds), placental abruption, and mothers can develop preeclampsia.

Rh disease

Rh is a protein found in the blood. Most people are Rh-positive, meaning they have this protein. Some people are Rh-negative, meaning this protein is absent. Gestational parents who are Rh-negative are at risk of having a baby with a form of anemia called Rh disease (March of Dimes, 2009). A father who is Rh-positive and a gestational parent who is Rh-negative can conceive a baby who is Rh-positive. Some of the fetus’s blood cells may get into the mother’s bloodstream and her immune system is unable to recognize the Rh factor. The immune system starts to produce antibodies to fight off what it thinks is a foreign invader. Once the pregnant person’s body produces immunity, the antibodies can cross the placenta and start to destroy the red blood cells of the developing fetus. As this process takes time, often the first Rh-positive baby is not harmed, but because the pregnant person’s body continues to produce antibodies to the Rh factor across their lifetime, subsequent pregnancies can pose a greater risk for an Rh-positive baby. In newborns, Rh disease can lead to jaundice, anemia, heart failure, brain damage, and death.

Weight gain during pregnancy

According to March of Dimes (2016f), during pregnancy, most people need only an additional 300 calories per day to aid in the growth of the fetus. Gaining too little or too much weight during pregnancy can be harmful. People who gain too little may have a baby with a low birth weight, while those who gain too much are likely to have a premature or large baby. There is also a greater risk for the gestational parent developing preeclampsia and diabetes, which can cause further problems during the pregnancy. Table 3.1 shows the healthy weight gain during pregnancy. Putting on the weight slowly is best. Gestational parents who are concerned about their weight gain should talk to their healthcare provider.

Table 3 Weight gain during pregnancy

| If you were a healthy weight before pregnancy | If you were underweight before pregnancy | If you were overweight before pregnancy | If you were obese before pregnancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| • gain 25-35lbs • 1-4½lbs in the first trimester and 1lb per week in the second and third trimesters |

• gain 28-40lbs • 1-4½lbs in the first trimester and a little more than 1lb per week thereafter |

• gain 12-25 lbs • 1-4½lbs in the first trimester and a little more than ½lb per week in the second and third trimesters |

• 11-20lbs • 1-4½lbs in the first trimester and less than ½lb per week in the second and third trimesters |

| Mothers of twins need to gain more in each category |

Maternal Stress

Stress represents the effects of any factor able to threaten the homeostasis of an organism; these either real or perceived threats are referred to as the “stressors” and comprise a long list of potential adverse factors, which can be emotional or physical. Because of a link in blood supply between a mother and fetus, it has been found that stress can leave lasting effects on a developing fetus, even before a child is born. The best-studied outcomes of fetal exposure to maternal prenatal stress are preterm birth and low birth weight. Maternal prenatal stress is also considered responsible for a variety of changes in the child’s brain and a risk factor for conditions such as behavioral problems, learning disorders, high levels of anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism, and schizophrenia. Furthermore, maternal prenatal stress has been associated with a higher risk for a variety of immune and metabolic changes in the child, such as asthma, allergic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and obesity (Konstantinos et al., 2017).

Depression

Depression is a significant medical condition in which feelings of sadness, worthlessness, guilt, and fatigue interfere with one’s daily functioning. Depression can occur before, during, or after pregnancy, and 1 in 7 pregnant people are treated for depression sometime between the year before pregnancy and the year after pregnancy (March of Dimes, 2015a). Women who have experienced depression previously are more likely to have depression while pregnant. Consequences of depression include the baby being born prematurely, having a low birth weight, being more irritable, less active, less attentive, and having fewer facial expressions. About 13% of pregnant people take an antidepressant during pregnancy. It is important that pregnant people taking antidepressants discuss the medication with a health care provider, as some medications can cause harm to the developing organism. In fact, birth defects are about 2 to 3 times more likely in people who are prescribed certain Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) for their depression.

Prenatal Assessment

A number of assessments are suggested to women as part of their routine prenatal care to find conditions that may increase the risk of complications for the mother and fetus (Eisenberg, et al., 1996). These can include blood and urine analyses and screening and diagnostic tests for birth defects.

Prenatal screening focuses on finding problems among a large population with affordable and noninvasive methods. The most common screening procedures are routine ultrasounds, blood tests, and blood pressure measurements. Screening can detect problems such as neural tube defects, anatomical defects, chromosome abnormalities, and gene mutations that would lead to genetic disorders and birth defects, such as spina bifida, cleft palate, Downs Syndrome, Tay–Sachs disease, sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, cystic fibrosis, muscular dystrophy, and fragile X syndrome. Some tests are designed to discover problems that primarily affect the health of the mother, such as PAPP-A to detect pre-eclampsia or glucose tolerance tests to diagnose gestational diabetes. Screening can also detect anatomical defects such as hydrocephalus, anencephaly, heart defects, and amniotic band syndrome.

Prenatal diagnosis focuses on pursuing additional detailed information once a particular problem has been found and can sometimes be more invasive. Common prenatal diagnosis procedures include amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling.

- Amniocentesis is a procedure in which a needle is used to withdraw a small amount of amniotic fluid and cells from the sac surrounding the fetus and later tested.

- Chorionic villus sampling is a procedure in which a small sample of cells is taken from the placenta and tested. Both amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling have a risk of miscarriage, and consequently, they are not done routinely.

Because of the miscarriage and fetal damage risks associated with amniocentesis and CVS procedures, many women prefer to first undergo screening so they can find out if the fetus’ risk of birth defects is high enough to justify the risks of invasive testing. Screening tests yield a risk score, which represents the chance that the baby has a birth defect; the most common threshold for high-risk is 1:270. A risk score of 1:300 would, therefore, be considered low-risk by many physicians. However, the trade-off between the risk of birth defects and the risk of complications from invasive testing is relative and subjective; some parents may decide that even a 1:1000 risk of birth defects warrants an invasive test, while others wouldn’t opt for an invasive test even if they had a 1:10 risk score.

Ultrasound is one of the main screening tests done in combination with blood tests. The ultrasound is a test in which sound waves are used to examine the fetus. There are two general types. Transvaginal ultrasounds are used early in pregnancy, while transabdominal ultrasounds are more common and used after 10 weeks of pregnancy (typically, 16 to 20 weeks). Ultrasounds are used to check the fetus for defects or problems. It can also find out the age of the fetus, location of the placenta, fetal position, movement, breathing and heart rate, amount of amniotic fluid in the uterus, and number of fetuses. Most women have at least one ultrasound during pregnancy, but if problems are noted, additional ultrasounds may be recommended.

There are three main purposes of prenatal diagnosis:

- to enable timely medical or surgical treatment of a condition before or after birth,

- to give the parents the chance to abort a fetus with the diagnosed condition, and

- to give parents the chance to prepare psychologically, socially, financially, and medically for a baby with a health problem or disability or for the likelihood of stillbirth.

Having this information in advance of birth means that healthcare staff, as well as parents, can better prepare themselves for the delivery of a child with a health problem. For example, Down Syndrome is associated with cardiac defects that may need intervention immediately upon birth.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines currently recommend that all pregnant women, regardless of age, be offered invasive testing to obtain a definitive diagnosis of certain birth defects. Therefore, most physicians offer diagnostic testing to all their patients, with or without prior screening, and let the patient decide.

Complications of Pregnancy

There are a number of common side effects of pregnancy. Not everyone experiences all of these, and neither do women experience them to the same degree. Although they are considered “minor,” these problems are potentially very uncomfortable. These side effects include nausea (particularly during the first 3-4 months of pregnancy as a result of higher levels of estrogen in the system), heartburn, gas, hemorrhoids, backache, leg cramps, insomnia, constipation, shortness of breath or varicose veins (as a result of carrying a heavy load on the abdomen). What is the cure? Delivery!

Major Complications

The following are some serious complications of pregnancy that can pose health risks to the woman and child and that often require hospitalization.

- Gestational diabetes is when a woman without diabetes develops high blood sugar levels during pregnancy.

- Hyperemesis gravidarum is the presence of severe and persistent vomiting, causing dehydration and weight loss. It is more severe than the more common morning sickness.

- Preeclampsia is gestational hypertension. Severe preeclampsia involves blood pressure over 160/110 with additional signs. Eclampsia is seizures in a pre-eclamptic patient.

- Deep vein thrombosis is the formation of a blood clot in a deep vein, most commonly in the legs.

- A pregnant woman is more susceptible to infections. This increased risk is caused by an increased immune tolerance during pregnancy, which prevents an immune reaction against the fetus.

- Peripartum cardiomyopathy is a decrease in heart function that occurs in the last month of pregnancy or up to six months post-pregnancy.

Miscarriage

Pregnancy loss is experienced in an estimated 20-40 percent of undiagnosed pregnancies and in another 10 percent of diagnosed pregnancies. Usually, the body aborts due to chromosomal abnormalities, and this typically happens before the 12th week of pregnancy. Cramping and bleeding result and normal periods should return after several months. Or it may be necessary to have a surgical procedure called D&E (dilation and evacuation). Some women are more likely to have repeated miscarriages due to chromosomal, amniotic, or hormonal problems, but miscarriage can also be a result of defective sperm (Carroll et al., 2003).

In the U.S., a pregnancy loss before the 20th week of pregnancy is referred to as a miscarriage, while the term stillbirth refers to the loss of a baby after 20 weeks gestation. A woman must still go through labor or a c-section to deliver her baby. Stillbirth affects about 1 in 160 births, and each year about 24,000 babies are stillborn in the United States. That is about the same number of babies that die during the first year of life, and it is more than 10 times as many deaths as the number that occur from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).

Maternal Mortality

Maternal mortality is unacceptably high. About 295,000 women died during and following pregnancy and childbirth in 2017. The vast majority of these deaths (94%) occurred in low-resource settings, and most could have been prevented.

The high number of maternal deaths in some areas of the world reflects inequalities in access to quality health services and highlights the gap between rich and poor. The campaign to make childbirth safe for everyone has led to the development of clinics accessible to those living in more isolated areas and training more midwives to assist in childbirth.

Most of these complications develop during pregnancy, and most are preventable or treatable. Other complications may exist before pregnancy but are worsened during pregnancy, especially if not managed as part of the woman’s care. The major complications that account for nearly 75% of all maternal deaths are:

- severe bleeding (mostly bleeding after childbirth)

- infections (usually after childbirth)

- high blood pressure during pregnancy (pre-eclampsia and eclampsia)

- complications from delivery

The remainder are caused by or associated with infections such as malaria or related to chronic conditions like cardiac diseases or diabetes.

Women in less developed countries have, on average, many more pregnancies than women in developed countries, and their lifetime risk of death due to pregnancy is higher. A woman’s lifetime risk of maternal death is the probability that a 15-year-old woman will eventually die from a maternal cause. In high-income countries, this is 1 in 5400, versus 1 in 45 in low-income countries. Every day in 2017, approximately 810 women died from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth. Trends in estimates of maternal mortality ratio (MMR) maternal deaths and lifetime risk of maternal death, 2000-2020

Even though maternal mortality in the United States is relatively rare today because of advances in medical care, it is still an issue that needs to be addressed. Sadly, about 700 women die each year in the United States as a result of pregnancy or delivery complications. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention define a pregnancy-related death as the death of a woman while pregnant or within 1 year of the end of a pregnancy–regardless of the outcome, duration, or site of the pregnancy–from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.

A new cause of death code was used during the PMSS review of deaths occurring in 2020, specifically for COVID-19, within the infection category. Infection became the most frequent underlying cause of death (27.5%), and COVID-19 accounted for 14.7% of all pregnancy-related deaths in 2020 (Centers for Disease Control, 2024).

Since the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System was implemented, the number of reported pregnancy-related deaths in the United States steadily increased from 7.2 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1987 to 24.9 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2020. The graph above shows trends in pregnancy-related mortality ratios between 1987 and 2020 (the latest available year of data).

Racial Disparity in Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes

In 2017–2019, the highest PRMR was among non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander persons. In 2020, the highest PRMR was among non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native persons. Variability in the risk of death by race-ethnicity may be due to several factors, including access to care, quality of care, prevalence of chronic diseases, structural racism, and implicit biases.

Racial Disparity in Birth Outcomes

In the United States, Black and American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) women are disproportionately more likely to die from complications related to pregnancy or childbirth than any other race; they are three or four times more likely than white women to die due to pregnancy-related death and are more likely to receive worse maternal care. Black women from higher income groups and with advanced education levels also have heightened risks—even tennis superstar Serena Williams had near-deadly complications during the birth of her daughter, Olympia. Why is this the case in our modern world? Watch this video to learn more.

Considerable racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related mortality exist. During 2014–2020, the pregnancy-related mortality ratios (see figure 11 above):

- 55.9 deaths per 100,000 live births for non-Hispanic Black women (up 14.2 since 2017)

- 63.4 deaths per 100,000 live births for non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native women (up 35.1 since 2017)

- 14.2 deaths per 100,000 live births for non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander women (up .4 since 2017)

- 18.1 deaths per 100,000 live births for non-Hispanic White women (up 4.7 since 2017)

- 22.6 deaths per 100,000 live births for Hispanic or Latina women (up 11 since 2017)

Variability in the risk of death by race/ethnicity may be due to several factors, including access to care, quality of care, prevalence of chronic diseases, structural racism, and implicit biases (Bailey et al., 2017; Howell, 2018; Hall et al., 2015).

In just three years, the pregnancy-related mortality rate for Black and AI/AN women has gone up tremendously. For AI/AN women, the CDC (Trost et al., 2024) considers that 91.7% of these deaths were preventable.

This U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website shows infant mortality rate statistics by ethnicity. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=23

This book provides a troubling study of the role that medical racism plays in the lives of black women who have given birth to premature and low birth weight infants. Davis, D. (2019). Reproductive Injustice (Vol. 7). New York: NYU Press.

This article details the experience of Dr. Tressie McMillan Cottom, a professor who dealt with pregnancy and birthing complications due to systemic racism. https://thewestsidegazette.com/i-was-pregnant-and-in-crisis-all-the-doctors-and-nurses-saw-was-an-incompetent-black-woman/

This website provides resources related to Black women and prenatal and maternal health. https://everymothercounts.org/anti-racist-reading/

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) has started a program called “Hear Her” to create awareness and provide better medical support for women of color. https://www.cdc.gov/hearher/index.html

This Ted Talk features a doula and journalist, Miriam Zoila Pérez, who explores the relationship between race, class. and illness. Further, Pérez discusses a radically compassionate prenatal care program that can buffer pregnant women from the stress that people of color face every day.

Compare the data on the two charts below. What differences do you see?

Causes of Pregnancy-related deaths in the United States 2017 – 2019

Causes of Pregnancy-related Deaths in the United States 2020

Conclusions

As you can see, what may seem like a simple process is, in fact, a beautiful and delicate journey. Each pregnancy and birth story is unique and comes with surprises and sometimes challenges. As medical technology has rapidly improved, women are empowered with more information and more choices when it comes to their pregnancy and birth. However, just because interventions are available does not mean that this is the path for all mothers. As we learned in the case of Serena Williams, even in the U.S., sometimes medical care can go awry. Each mother needs to be an active advocate for herself and her baby during her pregnancy and delivery.

Where do you think we are headed with how medical advances are used in pregnancy and delivery? More women are able to get pregnant with reproductive assistance, oftentimes past the age at which they would naturally conceive. At the beginning of the module, the topic of “designer babies” was introduced. After completing this module, do you think that we are headed towards this in the near future? What are the ethical ramifications?

Additional Supplemental Resources

Websites

- The Human Genome Project

- The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an inward voyage of discovery led by an international team of researchers looking to sequence and map all of the genes — together known as the genome — of members of our species, Homo sapiens. Beginning in October 1990 and completed in April 2003, the HGP gave us the ability, for the first time, to read nature’s complete genetic blueprint for building a human being.

- Institute for Behavioral Genetics

- Founded in 1967, IBG is one of the top research facilities in the world for genetic research on behavior. Data collection and analysis are ongoing for several internationally renowned studies, including the Colorado Adoption Project, the Colorado Twin Registry, the National Youth Survey Family Study, the Colorado Learning Disabilities Research Center, and the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health.

Videos

-

- Fertilization

- This video, created by Nucleus Medical Media, shows human fertilization, also known as conception. Shown at a cellular level magnification, sperm struggle through many obstacles in the female reproductive tract to reach the egg. Then, genetic material from the egg and a single sperm combine to form a new human being.

- Conception to birth- Visualized

- Image-maker Alexander Tsiaras shares a powerful medical visualization, showing human development from conception to birth and beyond.

- What are DNA and Genes?

- The Genetic Science Learning Center, sponsored by the University of Utah, delivers educational materials on genetics, bioscience, and health topics. All humans have the same genes arranged in the same order. And more than 99.9% of our DNA sequence is the same. But the few differences between us (all 1.4 million of them!) are enough to make each one of us unique.

- What is Inheritance?

- The Genetic Science Learning Center, sponsored by the University of Utah, delivers educational materials on genetics, bioscience, and health topics. This video explains the importance of genetic variation.

- Down Syndrome- Ability Awareness

- What comes to mind when you think of a person with Down Syndrome? Do you have a preconceived idea of their abilities? Chris Burke talks about his experience and his work at the National Down Syndrome Society.

- Prenatal Testing Options

- The University of Michigan provides this video explaining the difference between prenatal screening and diagnostic testing. Pregnant women are faced with the decision of whether to undergo prenatal screening and testing and, if so, which of the many options to choose from.

- Prenatal Development: What We Learn Inside the Womb

- Let’s watch what we experience and learn inside the womb from the fetus’ perspective.

- TED talk: How CRISPR lets us Edit our DNA

- Geneticist Jennifer Doudna co-invented a groundbreaking new technology for editing genes called CRISPR-Cas9. The tool allows scientists to make precise edits to DNA strands, which could lead to treatments for genetic diseases … but could also be used to create so-called “designer babies.” Doudna reviews how CRISPR-Cas9 works — and asks the scientific community to pause and discuss the ethics of this new tool.

- Fertilization

Attributions

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Waymaker Lifespan Development, authored by Sarah Carter and Sarah Hoiland for Lumen Learning and available under a Creative Commons Attribution license,

The section, In Vitro Fertilization, was provided by Ericka Goerling, PhD, and Emerson Wolfe, MS. Introduction to Human Sexuality is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

References

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet., 389(10077), 1453–1463. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X.

Berger, K. S. (2005). The developing person through the life span (6th ed.). New York: Worth.

Bregel, S. (2017). The lonely terror of postpartum anxiety. Retrieved from https://www.thecut.com/2017/08/the-lonely-terror-of-postpartum-anxiety.html

Berk, L. (2004). Development through the life span (3rd ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. 66

Betts, J. G., DeSaix, P., Johnson, E., Johnson, J. E., Korol, O., Kruse, D. H., Poe, B., Wise, J. A., & Young, K. A. (2019). Anatomy and physiology (OpenStax). Houston, TX: Rice University.

Bray, I., Gunnell, D., & Davey Smith, G. (2006). Advanced paternal age: how old is too old? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(10), 851–853. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.045179

Carrell, D. T., Wilcox, A. L., Lowry, L., Peterson, C. M., Jones, K. P., & Erikson, L. (2003). Elevated sperm chromosome aneuploidy and apoptosis in patients with unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 101(6), 1229-1235.

Carroll, J. L. (2007). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2005). Surgeon’s general’s advisory on alcohol use during pregnancy. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/documents/surgeongenbookmark.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Pelvic inflammatory disease. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/std/pid/stdfact-pid-detailed.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015a). Birthweight and gestation. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/birthweight.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015b) Genetic counseling. Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/genetics/genetic_counseling.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015c). Preterm birth. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pretermbirth.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015d). Smoking, pregnancy, and babies. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/diseases/pregnancy.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016a). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016b). HIV/AIDS prevention. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/prevention.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016c). HIV transmission. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/transmission.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016d). STDs during pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/std/pregnancy/stdfact-pregnancy.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Pregnancy-related deaths. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/maternal-deaths/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Pregnancy-mortality surveillance system. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/php/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance/index.html

Chiu, A. (2019, May 30). ‘She’s a miracle’: Born weighing about as much as ‘a large apple,’ Saybie is the world’s smallest surviving baby. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2019/05/30/world-smallest-surviving-baby-saybie-miracle/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.7c8d0bb6acf7 67

Conners, N.A., Bradley, R.H., Whiteside-Mansell, L., Liu, J.Y., Roberts, T.J., Burgdorf, K., & Herrell, J.M. (2003). Children of mothers with serious substance abuse problems: An accumulation of risks. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 29 (4), 743–758.

Cordier, S. (2008). Evidence for a role of paternal exposure in developmental toxicity. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology, 102, 176-181.

Eisenberg, A., Murkoff, H. E., & Hathaway, S. E. (1996). What to expect when you’re expecting. New York: Workman Publishing.

Figdor, E., & Kaeser, L. (1998). Concerns mount over punitive approaches to substance abuse among pregnant women. The Guttmacher report on public policy, 1(5), 3–5.

Fraga, M. F., Ballestar, E., Paz, M. F., Ropero, S., Setien, F., Ballestar, M. L., … Esteller, M. (2005). Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (USA), 102, 10604-10609. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0500398102

Goerling, E. and Wolfe, E. (2023). Introduction to human sexuality. Open Oregon. Retrieved June 5th, 2024, from https://openwa.pressbooks.pub/hsspring2023/ CC BY-NC SA 4.0 license.

Gottlieb, G. (1998). Normally occurring environmental and behavioral influences on gene activity: From central dogma to probabilistic epigenesis. Psychological Review, 105, 792-802.

Gottlieb, G. (2000). Environmental and behavioral influences on gene activity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9, 93-97.

Gottlieb, G. (2002). Individual development and evolution: The genesis of novel behavior. New York: Oxford University Press.

Grossman, D., & Slutsky, D. (2017). The effect of an increase in lead in the water system on fertility and birth outcomes: The case of Flint, Michigan. Economics Faculty Working Papers Series. Retrieved from http://www2.ku.edu/~kuwpaper/2017Papers/201703.pdf

Hall, D. W. (2004). Meiotic drive and sex chromosome cycling. Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution, 58(5), 925–931. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00426.x

Hall W.J., Chapman M.V., Lee K.M., Merino, Y.M., Thomas, T. W., Payne B. K., Eng, E., Day, S. H., and Coyne-Beasley, T. (2015). Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 105 (e60–e76). https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903

Howell EA. (2018). Reducing disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 61(2), 387–399. https://doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0000000000000349

Jos, P. H., Marshall, M. F., & Perlmutter, M. (1995). The Charleston policy on cocaine use during pregnancy: A cautionary tale. The Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics, 23(2), 120-128.

Maier, S.E., & West, J.R. (2001). Drinking patterns and alcohol-related birth defects. Alcohol Research & Health, 25(3), 168-174.

March of Dimes. (2009). Rh disease. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/rh-disease.aspx

March of Dimes. (2012a). Rubella and your baby. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/baby/rubella-and-your-baby.aspx 68

March of Dimes. (2012b). Stress and pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy/stress-and-pregnancy.aspx

March of Dimes. (2012c). Teenage pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/teenage-pregnancy.pdf

March of Dimes. (2012d). Toxoplasmosis. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/toxoplasmosis.aspx

March of Dimes. (2013). Sexually transmitted diseases. Retrieved http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/sexually-transmitted-diseases.aspx

March of Dimes. (2014). Pesticides and pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy/pesticides-and-pregnancy.aspx

Mayo Clinic. (2015). Male infertility. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/male-infertility/basics/definition/con-20033113

March of Dimes. (2015a). Depression during pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/depression-during-pregnancy.aspx

March of Dimes. (2015b). Gestational diabetes. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/gestational-diabetes.aspx

March of Dimes. (2015c). High blood pressure during pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/high-blood-pressure-during-pregnancy.aspx

March of Dimes. (2015d). Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/neonatal-abstinence-syndrome-(nas).aspx

March of Dimes. (2016). Pregnancy after age 35. http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy-after-age-35.aspx

March of Dimes. (2016a). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/complications/fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorders.aspx

March of Dimes. (2016b). Identifying the causes of birth defects. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/research/identifying-the-causes-of-birth-defects.aspx

March of Dimes. (2016c). Marijuana and pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy/marijuana.aspx

March of Dimes. (2016d). Pregnancy after age 35. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy-after-age-35.aspx

March of Dimes. (2016e). Prescription medicine during pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy/prescription-medicine-during-pregnancy.aspx

March of Dimes. (2016f). Weight gain during pregnancy. Retrieved from http://www.marchofdimes.org/pregnancy/weight-gain-during-pregnancy.aspx

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Osterman, M., Curtin, S. C., & Mathews, T. J. (2015). Births: Final data for 2013. National Vital Statistics Reports, 64(1), 1-65.

Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Ectopic pregnancy. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ectopic-pregnancy/symptoms-causes/syc-20372088

Morgan, M.A., Goldenberg, R.L., & Schulkin, J. (2008) Obstetrician-gynecologists’ practices regarding preterm birth at the limit of viability. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 21, 115-121.

Moore, K. L., & Persaud, T. V. (1998). Before we are born (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2013). Preeclampsia. Retrieved from https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/preeclampsia/conditioninfo/Pages/risk.aspx 69

National Public Radio. (Producer). (2015, November 18). In Tennessee, giving birth to a drug-dependent baby can be a crime [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/templates/transcript.php?storyld=455924258

Nippoldt, T.B. (2015). How does paternal age affect a baby’s health? Mayo Clinic. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/getting-pregnant/expert-answers/paternal-age/faq- 20057873

Pettersson, E., Larsson, H., D’Onofrio, B., Almqvist, C., & Lichtenstein, P. (2019). Association of fetal growth with general and specific mental health conditions. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(5), 536-543. Doi:10.1001jamapsychiatry.2018.4342

Nippoldt, T.B. (2015). How does paternal age affect a baby’s health? Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/getting-pregnant/expert-answers/paternal-age/faq-20057873

Regev, R.H., Lusky, T. Dolfin, I. Litmanovitz, S. Arnon, B. & Reichman. (2003). Excess mortality and morbidity among small-for-gestational-age premature infants: A population based study. Journal of Pediatrics, 143, 186-191.

Rehan, V. K., Sakurai, J. S., & Torday, J. S. (2011). Thirdhand smoke: A new dimension to the effects of cigarette smoke in the developing lung. American Journal of Physiology: Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, 301(1), L1-8.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (1997). Fetal Awareness: Report of a Working Party. London: RCOG Press.

Someji, S., & Beltrán-Sánchez, H. (2019). Association of maternal cigarette smoking and smoking cessation with preterm birth. JAMA Network Open, 2(4), e192514. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2514

Streissguth, A.P., Barr, H.M., Kogan, J. & Bookstein, F. L. (1996). Understanding the occurrence of secondary disabilities in clients with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) and Fetal Alcohol Effects (FAE). Final Report to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), August. Seattle: University of Washington, Fetal Alcohol & Drug Unit, Tech. Rep. No. 96-06.

Stiles, J., & Jernigan, T. L. (2010). The basics of brain development. Neuropsychology Review, 20(4), 327–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-010-9148-4

Sun, F., Sebastiani, P., Schupf, N., Bae, H., Andersen, S. L., McIntosh, A., Abel, H., Elo, I., & Perls, T. (2015). Extended maternal age at birth of last child and women’s longevity in the Long Life Family Study. Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society, 22(1), 26-31.

Tong, V. T., Dietz, P.M., Morrow, B., D’Angelo, D.V., Farr, S.L., Rockhill, K.M., & England, L.J. (2013). Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy — Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 40 Sites, 2000–2010. Surveillance Summaries, 62(SS06), 1-19. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6206a1.htm

Trost SL, Busacker A, Leonard M, et al. (2024). Pregnancy-Related Deaths Among American Indian or Alaska Native Persons: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 38 U.S. States, 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

United States National Library of Medicine. (2015). Fetal development. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002398.htm

World Health Organization. (2010, September 15). Maternal deaths worldwide drop by a third, WHO. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/ 2010/maternal_mortality_20100915/en/index.html