Section 7: Middle to Late Childhood

7.3 Psychosocial Development in Middle to Late Childhood

Stressors and Supports in Middle Childhood

Family Tasks

One of the ways to assess the quality of family life is to consider the tasks of families. There are many different types of family or family structure. The structures refer to the formation of relationships among a household, such as single-parent families, two-parent families, adoptive families, foster families, families raised by grandparents, same-sex parent families, etc. There are numerous structures of families. However, family function, or the way families function to meet each others’ needs, is paramount.

Berger (2005) lists five family functions:

- Providing food, clothing, and shelter

- Encouraging Learning

- Developing self-esteem

- Nurturing friendships with peers

- Providing harmony and stability

Notice that in addition to providing food, shelter, and clothing, families are responsible for helping the child learn, relate to others, and have a confident sense of self. The family provides a harmonious and stable environment for living. A good home environment is one in which the child’s physical, cognitive, emotional, and social needs are adequately met. Sometimes, families emphasize physical needs but ignore cognitive or emotional needs. Other times, families pay close attention to physical needs and academic requirements but may fail to nurture the child’s friendships with peers or guide the child toward developing healthy relationships. Parents might want to consider how it feels to live in the household. Is it stressful and conflict-ridden? Is it a place where family members enjoy being?

Family Structure

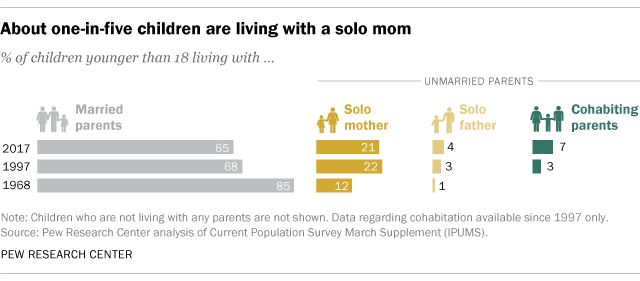

Family structures have changed significantly over the years. In 1960, 92% of children resided with married parents, while only 5% had parents who were divorced or separated, and 1% resided with parents who had never been married. By 2008, 70% of children resided with married parents, 15% had parents who were divorced or separated, and 14% resided with parents who had never married (Pew Research Center, 2010). In 2017, only 65% of children lived with two married parents, while 32% (24 million children younger than 18) lived with an unmarried parent (Livingston, 2018). Some 3% of children were not living with any parents, according to the U.S. Census Bureau data.

Most children in unmarried-parent households in 2017 were living with a solo mother (21%), but a growing share were living with cohabiting parents (7%) or a sole father (4%) (see Figure 4.3). The increase in children living with solo or cohabiting parents is thought to be due to overall declines in marriage, combined with increases in divorce. Of concern is that children who live with a single parent are also more likely to be living in reduced socioeconomic circumstances. Specifically, while only 8% of married couples live below the poverty line, 30% of solo mothers, 17% of solo fathers, and 16% of families with a cohabitating couple live in poverty (Livingston, 2018).

Divorce and its effects on children

A lot of attention has been given to the impact of divorce on the lives of children. The assumption has been that divorce has a strong, negative impact on the child and that single-parent families are deficient in some way. Research suggests 75-80 percent of children and adults who experience divorce suffer no long-term effects (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). Children of divorce and children who have not experienced divorce are more similar than different (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002).

Other research suggests that divorce typically is difficult for children. For example, Weaver and Schofield (2015) selected a subsample of families from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development and found that children from divorced families had significantly more behavior problems than those from a matched sample of children from non-divorced families. These problems were evident immediately after the separation and also in early and middle adolescence.

An analysis of the factors that make adjustment to divorce easier or harder indicated that children exhibited more externalizing behaviors if the family had fewer financial resources before the separation. Researchers suggested that perhaps a lower income and lack of educational and community resources contributed to the stress involved in the divorce. Additional factors predicting fewer behavior problems included a more supportive and stimulating post-divorce home and a mother who was more sensitive and less depressed.

Mintz (2004) suggests that the alarmist view of divorce was due in part to the newness of divorce when rates in the United States began to climb in the late 1970s. Adults reacting to the change grew up in the 1950s when rates were low. As divorce has become more common and there is less stigma associated with divorce, this view has changed somewhat. Social scientists have operated from the divorce as a deficit model emphasizing the problems of being from a “broken home” (Seccombe &Warner, 2004). More recently, a more objective view of divorce, re-partnering, and remarriage indicates that divorce, remarriage, and life in stepfamilies can have a variety of effects. The exaggeration of the negative consequences of divorce has left the majority of those who do well hidden and subjected them to unnecessary stigma and social disapproval (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002).

The tasks of families listed above are functions that can be fulfilled in a variety of family types, just intact, two-parent households. Harmony and stability can be achieved in many family forms, and when it is disrupted, either through a divorce, efforts to blend families or any other circumstances, the child suffers (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002).

Factors Affecting the Impact of Divorce

As you look at the consequences (both pro and con) of divorce and remarriage on children, keep these family functions in mind. Some negative consequences are a result of financial hardship rather than divorce per se (Drexler, 2005). Some positive consequences reflect improvements in meeting these functions. For instance, we have learned that positive self-esteem comes in part from a belief in the self and one’s abilities rather than merely being complemented by others. In single-parent homes, children may be given more opportunities to discover their own abilities and gain the independence that fosters self-esteem. If divorce leads to fighting between the parents and the child is included in these arguments, the self-esteem may suffer.

Certain losses are inevitable in a divorce. Children miss the parent they no longer see as frequently, as well as any other family members who become estranged because of the divorce. Children may grieve the loss of the family as a unit, and reminisce about “the good old days” when the whole family lived together. The process of divorce is typically accompanied by change, disruption, and confusion, as well as increased family conflict. Because they are themselves dealing with the divorce, parents are typically stressed out and fewer resources are available for parenting.

The impact of divorce on children depends on a number of factors. The degree of conflict prior to the divorce plays a role. If the divorce means a reduction in tensions, the child may feel relief. If the parents have kept their conflicts hidden, the announcement of a divorce can come as a shock and be met with enormous resentment. Another factor that has a great impact on the child concerns the financial hardships they may suffer, especially if financial support is inadequate. Another difficult situation for children of divorce is the position they are put into if the parents continue to argue and especially if they bring the children into those arguments.

Short-term consequences: In roughly the first year following divorce, children may exhibit some of these short-term effects:

- Grief over losses suffered. The child will grieve the loss of the parent they no longer see as frequently. The child may also grieve about other family members that are no longer available. Grief sometimes comes in the form of sadness, but it can also be experienced as anger or withdrawal. Preschool-aged boys may act out aggressively, while the same-aged girls may become more quiet and withdrawn. Older children may feel depressed.

- Reduced Standard of Living. Very often, divorce means a change in the amount of money coming into the household. Children experience new constraints on spending or entertainment. School-aged children, especially, may notice that they can no longer have toys, clothing, or other items to which they’ve grown accustomed. The custodial parent may experience stress at not being able to rely on child support payments or having the same level of income as before. This can affect decisions regarding healthcare, vacations, rents, mortgages, and other expenditures. The stress can result in less happiness and relaxation in the home. The parent who has to take on more work may also be less available to the children.

- Adjusting to Transitions. Children may also have to adjust to other changes accompanying a divorce. The divorce might mean moving to a new home, changing schools or friends, or leaving a neighborhood that has meant a lot to them.

Long-Term consequences: The following are some effects found after the first year of a divorce:

- Economic/Occupational Status. One of the most commonly cited long-term effects of divorce is that children of divorce may have lower levels of education or occupational status. This may be a consequence of lower income and resources for funding education rather than divorce per se. In those households where economic hardship does not occur, there may be no impact on education or occupational status (Drexler, 2005).

- Improved Relationships with the Custodial Parent (usually the mother): The majority of custodial parents are mothers (approximately 80.4 percent) and

19.6 percent of custodial parents are fathers. Shared custody is on the rise, however, and shows promising social, academic, and psychological results for the children. Children from single-parent families talk to their mothers more often than children of two-parent families (McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994). Most children of divorce lead happy, well-adjusted lives and develop stronger, positive relationships with their custodial parent (Seccombe & Warner, 2004). In a study of college-age respondents, Arditti (1999) found that increasing closeness and a movement toward more democratic parenting styles were experienced. Others have also found that relationships between mothers and children become closer and stronger (Guttman, 1993) and suggest that greater equality and less rigid parenting is beneficial after divorce (Steward et al., 1997). - Greater emotional independence in sons. Drexler (2005) notes that sons who are raised by mothers only develop an emotional sensitivity to others that is beneficial in relationships.

- Feeling more anxious in their own love relationships. Children of divorce may feel more anxious about their own relationships as adults. This may reflect a fear of divorce if things go wrong, or it may be a result of setting higher expectations for their own relationships.

- Adjustment of the custodial parent. Furstenberg and Cherlin (1991) believe that the primary factor influencing the way that children adjust to divorce is the way the custodial parent adjusts to the divorce. If that parent is adjusting well, the children will benefit. This may explain a good deal of the variation we find in children of divorce. Adults going through divorce should consider good self-care as beneficial to the children as self-indulgent.

- Mental health issues: Some studies suggest that anxiety and depression that are common in children and adults within the first year of divorce may actually not resolve. A 15-year study by Bohman et al. (2017) suggests that parental separation significantly increases the risk for depression 15 years later when depression rates were compared to matched controls. In fact, the risk of depression was related more strongly to parental conflict and parental separation than it was to parental depression!

Helping children adjust to divorce. According to Arkowitz and Lilienfeld (2013), long-term harm from parental divorce is not inevitable, however, and children can navigate the experience successfully. A variety of factors can positively contribute to the child’s adjustment. For example, children manage better when parents limit conflict and provide warmth, emotional support, and appropriate discipline. Further, children cope better when they reside with a well-functioning parent and have access to social support from peers and other adults. Those at a higher socioeconomic status may fare better because some of the negative consequences of divorce are a result of financial hardship rather than divorce per se (Anderson, 2014; Drexler, 2005). It is important when considering the research findings on the consequences of divorce for children to consider all the factors that can influence the outcome, as some of the negative consequences associated with divorce are due to preexisting problems (Anderson, 2014). Although they may experience more problems than children from non-divorced families, most children of divorce lead happy, well-adjusted lives and develop strong, positive relationships with their custodial parents (Seccombe & Warner, 2004).

In a study of college-age respondents, Arditti (1999) found that increasing closeness and a movement toward more democratic parenting styles were experienced following divorce. Children from single-parent families also talk to their mothers more often than children of two-parent families (McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994). Others have also found that relationships between mothers and children become closer and stronger (Guttman, 1993) and suggest that greater equality and less rigid parenting are beneficial after divorce (Stewart, Copeland, Chester, Malley, & Barenbaum, 1997).

For more information on how to help children adjust, here is guide from the American Academy of Pediatrics on Helping Children and Families Deal with Divorce.

For advice to parents, here is a set of informal recommendations.

Is cohabitation and remarriage more difficult than divorce for children? The remarriage of a parent may be a more difficult adjustment for a child than the divorce of a parent (Seccombe & Warner, 2004). Parents and children typically have different ideas about how the stepparent should behave. Parents and stepparents are more likely to see the stepparent’s role as that of a parent. A more democratic style of parenting may become more authoritarian after a parent remarries. Biological parents are more likely to continue to be involved with their children jointly when neither parent has remarried. They are least likely to jointly be involved if the father has remarried and the mother has not. Cohabitation can be difficult for children to adjust to because cohabiting relationships in the United States tend to be short-lived. About 50 percent last less than 2 years (Brown, 2000). A child who starts a relationship with the parent’s live-in partner may have to sever this relationship later. Even in long-term cohabiting relationships, once it is over, continued contact with the child is rare.

Blended families

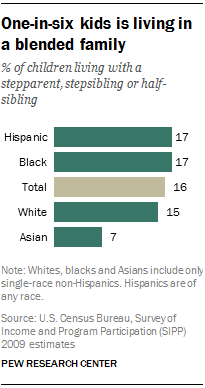

One in six children (16%) live in a blended family (Pew Research Center, 2015). As can be seen in Figure 4.5, Hispanic, Black, and White children are equally likely to be living in blended families. In contrast, children of Asian descent are more likely to be living with two married parents, often in their first marriage. Blended families are not new. In the 1700s-1800s, there were many blended families, but they were created because one parent (usually the mother) died and the other parent remarried. Most blended families today are a result of divorce and remarriage, and such origins lead to new considerations. Blended families are different from intact families and more complex in a number of ways that can pose unique challenges to those who seek to form successful blended family relationships (Visher & Visher, 1985). Children may be a part of two households, and if each has different rules, the situation can be confusing.

Members of blended families may not be as sure that others care and may require more demonstrations of affection for reassurance. For example, stepparents expect more gratitude and acknowledgment from the stepchild than they would with a biological child. Stepchildren experience more uncertainty/insecurity in their relationship with their parents and fear the parents will see them as sources of tension. Stepparents may feel guilty for a lack of feelings they may initially have toward their partner’s children. Children who are required to respond to the parent’s new mate as though they were the child’s “real” parent often react with hostility, rebellion, or withdrawal. This occurs especially if there has not been sufficient time for the relationship to develop organically.

Sexual Abuse in Middle Childhood

Researchers estimate that 1 out of 4 girls and 1 out of 10 boys have been sexually abused (Valente, 2005). The median age for sexual abuse is 8 or 9 years for both boys and girls, around the first signs of physical puberty (Finkelhor et al., 1990). Most boys and girls are sexually abused by a male. Childhood sexual abuse is defined as any sexual contact between a child and an adult or a much older child. Incest refers to sexual contact between a child and family members. In each of these cases, the child is exploited by an older person without regard for the child’s developmental immaturity and inability to understand the sexual behavior (Steele, 1986).

Although rates of sexual abuse are higher for girls than for boys, boys may be less likely to report abuse because of the cultural expectation that boys should be able to take care of themselves and because of the stigma attached to homosexual encounters (Finkelhor et. al. 1990). Girls are more likely to be victims of incest, and boys are more likely to be abused by someone outside the family. Sexual abuse can create feelings of self-blame, betrayal, and feelings of shame and guilt (Valente, 2005). Sexual abuse is particularly damaging when the perpetrator is someone the child trusts. Victims of sexual abuse may suffer from depression, anxiety, problems with intimacy, and suicide (Valente, 2005). Sexual abuse has additional impacts as well. Studies suggest that children who have been sexually abused have an increased risk of eating disorders and sleep disturbances Further, sexual abuse can lead to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Being sexually abused as a child can have a powerful impact on self-concept. The concept of false self-training (Davis, 1999) refers to holding a child to adult standards while denying the child’s developmental needs. Sexual abuse is just one example of false self-training. Children are held to adult standards of desirableness and sexuality while their level of cognitive, psychological, and emotional immaturity is ignored. Consider how confusing it might be for a 9-year-old girl who has physically matured early to be thought of as a potential sex partner. Her cognitive, psychological, and emotional state does not equip her to make decisions about sexuality or, perhaps, to know that she can say no to sexual advances. She may feel like a 9-year-old in all ways and be embarrassed and ashamed of her physical development. Girls who mature early have problems with low self-esteem because of the failure of others (family members, teachers, ministers, peers, advertisers, and others) to recognize and respect their developmental needs. Overall, youth are more likely to be victimized because they do not have control over their contact with offenders (parents, babysitters, etc.) and have no means of escape (Finkelhor and Dzuiba-Leatherman, in Davis, 1999).

Conclusion

Up until middle childhood, the process of development isn’t usually as structured as it becomes during middle childhood when children enter into the formal education setting. Children in school are taught new ways of thinking about things that they already know—they learn why they structure sentences the way they do, and they learn new words not through hearing them from others but from lists provided by teachers or determined by committees. They are even taught how to play sports in specific ways with explicit rules that they get tested on in written form. This is quite a departure from the organic learning of younger years.

Learning in this new way is difficult for some children who have never had to sit down for formal instruction. Structured learning can also shed light on learning difficulties and learning disabilities. Educators today are trained to recognize the signs of many learning disabilities so that children can get help early on in their academic careers.

Developing social relationships in the school environment and keeping up with the changing relationships at home can be difficult tasks for children during middle childhood. Children begin the period relatively dependent on parents and by the end of the period, children should be able to act autonomously in terms of decision making and caring for themselves. This change may feel quick to parents, and it can be difficult for them to let go of control and allow the child to make more decisions. In order for the child to continue healthy development, though, that gradual letting go is necessary. Parents should pay close attention to their children to recognize signs that the child is capable of taking on new responsibilities. This will help the child continue to develop their skills, their sense of self, their sense of place in the family, and their sense of place in the greater community.

Additional Resources

Websites

- Autism Science Foundation (Links to an external site.)

- An organization supporting autism research by providing funding and other assistance to scientists and organizations conducting, facilitating, publicizing, and disseminating autism research. The organization also provides information about autism to the general public and serves to increase awareness of autism spectrum disorders and the needs of individuals and families affected by autism.

- Stop Bullying (Links to an external site.)

- There are many types of bullying, including physical, verbal, social, and cyber. With bullying affecting so many people, it is important to understand what it is and how to respond to it and prevent it. This Web site provides a plethora of resources for a variety of audiences.

Videos

- Crash Course Video #13 – How We Make Memories

- This video on how we make memories includes information on topics such as stages of memory, mnemonics, and levels of processing. Closed captioning available.

- Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

- This video summarizes Kohlberg’s stages of moral development. The stages themselves are structured in three levels: Pre-Conventional, Conventional, and Post-Conventional.

- Heinz Dilemma – Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development (Interactive Animation)

- Heinz’s dilemma was conceived by Lawrence Kohlberg in its original research on the stages of moral development. This video presents a simplified version of the experiment.

- What is dyslexia? – Kelli Sandman-Hurley- TEDed

- Dyslexia affects up to 1 in 5 people, but the experience of dyslexia isn’t always the same. This difficulty in processing language exists along a spectrum — one that doesn’t necessarily fit with labels like “normal” and “defective.” Kelli Sandman-Hurley urges us to think again about dyslexic brain function and to celebrate the neurodiversity of the human brain.

- Piaget – Stage 3 – Concrete – Reversibility

- Does this child understand the concept of reversibility? Which stage would that put her in?

- Egocentrism

- The Three Mountain Problem was devised by Piaget to test whether a child’s thinking was egocentric, which was also a helpful indicator of whether the child was in the preoperational stage or the concrete operational stage of cognitive development. Which stage are these children in?

- ADHD at School

- ADHD stands for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and is considered a mental disorder. Children with ADHD have trouble paying attention, are hyperactive, and have difficulty controlling their behavior. To understand how it affects children in school, let’s look at the story of Leo, a 12-year-old boy who is going to school with the best intentions but is struggling hard to succeed.

- The World Needs All Kinds of Minds- TED talk

- Temple Grandin, diagnosed with autism as a child, talks about how her mind works — sharing her ability to “think in pictures,” which helps her solve problems that neurotypical brains might miss. She makes the case that the world needs people on the autism spectrum: visual thinkers, pattern thinkers, verbal thinkers, and all kinds of smart geeky kids.

Attributions

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Child Growth and Development by College of the Canyons, Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, and Dawn Rymond and is used under a CC BY 4.0 international license

Plays the Thing, Cambridge University is licensed under a CC BY 4.0

Additional written material by Dan Grimes & Brandy Brennan, Portland State University, and is licensed CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0

References

Anderson, J. (2018). The impact of family structure on the health of children: Effects of divorce. The Linacre Quarterly 81(4), 378–387.

Arditti, J. A. (1999). Rethinking relationships between divorced mothers and their children: Capitalizing on family strengths. Family Relations, 48, 109-119.

Arkowicz, H., & Lilienfeld. (2013). Is divorce bad for children? Scientific American Mind, 24(1), 68-69.

Asher, S. R., & Hymel, S. (1981). Children’s social competence in peer relations: Sociometric and behavioral assessment. In J. K. Wine & M. D. Smye (Eds.), Social competence (pp. 125-157). New York: Guilford Press.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action; A social-cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Berkowitz, M., & Gibbs, J. (1983). Measuring the Developmental Features of Moral Discussion. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 29(4), 399-410. Retrieved September 9, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23086309

Bigelow, B. J. (1977). Children’s friendship expectations: A cognitive developmental study. Child Development, 48, 246–253.

Bigelow, B. J., & La Gaipa, J. J. (1975). Children’s written descriptions of friendship: A multidimensional analysis. Developmental Psychology, 11(6), 857-858.

Boulton, M. J. (1999). Concurrent and longitudinal relations between children’s playground behavior and social preference, victimization, and bullying. Child Development, 70, 944-954.

Brown, S. L. (2000). Union transitions among cohabitors: The significance of relationship assessments and expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 833-846.

Cillessen, A. H., & Mayeaux, L. (2004). From censure to reinforcement: Developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Development, 75, 147-163.

Clark, M. L., & Bittle, M. L. (1992). Friendship expectations and the evaluation of present friendships in middle childhood and early adolescence. Child Study Journal, 22, 115–135.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87

Davis, N. J. (1999). Youth crisis: Growing up in the high-risk society. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Drexler, P. (2005). Raising boys without men. Emmaus, PA: Rodale.

Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. NY: Norton & Company.

Finkelhor, D. (1984). Child sexual abuse: New theory and research. New York: Free Press.

Finkelhor, D., Hotaling, G., Lewis, I. A., & Smith, C. (1990). Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse and Neglect, 14, 19-28.

Furstenberg, F. F., & Cherlin, A. J. (1991). Divided families: What happens to children when parents part. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Guttmann, J. (1993). Divorce in psychosocial perspective: Theory and research. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834.

Hampel, P., & Petermann, F. (2005). Age and Gender Effects on Coping in Children and Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(2), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-3207-9

Hetherington, E. M., & Kelly, J. (2002). For better or for worse: Divorce reconsidered. New York: W.W. Norton.

Jaffee, S., & Hyde, J. S. (2000). Gender differences in moral orientation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 703–726.

Killen, M., Rutland, A., & Yip, T. (2016). Equity and justice in developmental science: Discrimination, social exclusion, and intergroup attitudes. Child Development, 87(5), 1317-1336.

Klima, T., & Repetti, R. L. (2008). Children’s peer relations and their psychological adjustment: Differences between close friends and the larger peer group. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 54, 151-178.

Kohlberg, L. (1963). The development of children’s orientations toward a moral order: Sequence in the development of moral thought. Vita Humana, 16, 11-36.

Kohlberg, L. (1968). The child as a moral philosopher. Psychology Today, 25-30.

Kohlberg, L. (1984). The psychology of moral development: Essays on moral development (Vol. 2, p. 200). San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row.

Livingston, G. (2018). About one-third of U.S. children are living with an unmarried parent. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/27/about-one-third-of-u-s-children-are-living-with-an-unmarried-parent/Mason, M. G., & Gibbs, J. C. (1993). Social Perspective Taking and Moral Judgment among College Students. Journal of Adolescent Research, 8(1), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/074355489381008

McLanahan, S., & Sandefur, G. D. (1994). Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Pettit, G. S., Clawson, M. A., Dodge, K. A., & Bates, J. E. (1996). Stability and change in peer-rejected status: The role of child behavior, parenting, and family ecology. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 42(2), 267-294.

Pew Research Center. (2010). New family types. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/11/18/vi-new-family-types/

Pew Research Center. (2015). Parenting in America. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/12/2015-12-17_parenting-in-america_FINAL.pdf

Reid, S. (2017). 4 questions for Mitch Prinstein. Monitor on Psychology, 48(8), 31-32.

Rest, J. (1979). Development in judging moral issues. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Richter, D, & Lemola, S. (2017). Growing up with a single mother and life satisfaction in adulthood: A test of mediating and moderating factors. PLOS ONE 12(6): e0179639. Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0179639

Saarni, C. (1999). The development of emotional competence. New York: Guilford Press.

Schwartz, D., Lansford, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2014). Peer victimization during middle childhood as a lead indicator of internalizing problems and diagnostic outcomes in late adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 44, 393-404.

Seccombe, K., & Warner, R. L. (2004). Marriages and families: Relationships in social context. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Seifert, K. (2011). Educational psychology. Houston, TX: Rice University

Selman, Robert L. (1980). The growth of interpersonal understanding. London: Academic Press

Steele, B.F. (1986). Notes on the lasting effects of early child abuse throughout the life cycle. Child Abuse & Neglect 10(3), 283-291.

Stewart, A. J., Copeland, Chester, Malley, & Barenbaum. (1997). Separating together: How divorce transforms families. New York: Guilford Press.

Temke, Mary W. 2006. “The Effects of Divorce on Children.” Durham: University of New Hampshire. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

Turiel, E. (1998). The development of morality. In W. Damon (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Socialization (5th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 863–932). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, November 5). Effects of Bullying. stopbullying.gov. https://www.stopbullying.gov/bullying/effects

Valente, S. M. (2005). Sexual Abuse of Boys. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 18, 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2005.00005.x

Visher, E. B., & Visher, J. S. (1985). Stepfamilies are different. Journal of Family Therapy, 7(1), 9-18.

Walker, L. J. (1995). Sexism in Kohlberg’s moral psychology? In W. M. Kurtines & J. L. Gerwitz (Eds.), Moral development: An introduction (pp. 83-107). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Walker, L. J., & Taylor, J. H. (1991). Stage transitions in moral reasoning: A longitudinal study of developmental processes. Developmental Psychology, 27(2), 330–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.27.2.330

Weaver, J. M., & Schofield, T. J. (2015). Mediation and moderation of divorce effects on children’s behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(1), 39-48. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/fam0000043