Section 10: Middle Adulthood

10.4 Relationships in Middle Adulthood

How relationships are maintained and changed during middle adulthood

The importance of establishing and maintaining relationships in middle adulthood is now well established in the academic literature—there are now thousands of published articles purporting to demonstrate that social relationships are integral to any and all aspects of subjective well-being and physiological functioning, and these help to inform actual healthcare practices. Studies show an increased risk of dementia, cognitive decline, susceptibility to vascular disease, and increased mortality in those who feel isolated and alone. However, loneliness is not confined to people living a solitary existence. It can also refer to those who endure a perceived discrepancy in the socio-emotional benefits of interactions with others, either in number or nature. One may have an expansive social network and still feel a dearth of emotional satisfaction in one’s own life.

Socioemotional selectivity theory (SST) predicts a quantitative decrease in the number of social interactions in favor of those bringing greater emotional fulfillment. Over the past thirty years or more, there have been significant social changes that have had a large effect on human bonding. These have affected the way we manage our emotional interactions and the manner in which society views, shapes, and supports that emotional regulation. Government policy has also changed and had a profound influence on how families are shaped, reshaped, and operated as social and economic agents.

Chapter Objectives

- Explain how relationships are maintained and changed during middle adulthood

- Describe the link between intimacy and subjective well-being

- Describe the different types of grandparents

- Discuss issues related to family life in middle adulthood

- Explore the impact of religion and spirituality within the lifespan

Family Issues and Considerations

The sandwich generation refers to adults who have at least one parent age 65 or older and are either raising their own children or providing support for their grown children. According to a recent Pew Research survey, 47% of middle-aged adults are part of this sandwich generation (Parker & Patten, 2013). In addition, 15% of middle-aged adults are providing financial support to an older parent while raising or supporting their own children (see Figure 8.12). According to the same survey, almost half (48%) of middle-aged adults have supported their adult children in the past year, and 27% are the primary source of support for their grown children.

Seventy-one percent of the sandwich generation is aged 40-59, 19% are younger than 40, and 10% are 60 or older. Hispanics are more likely to find themselves supporting two generations: 31% have parents 65 or older and a dependent child, compared with 24% of whites and 21% of blacks (Parker & Patten, 2013). Women are more likely to take on the role of care provider for older parents in the U.S. and Germany (Pew Research, 2015). About 20% of women say they have helped with personal care, such as getting dressed or bathing, of aging parents in the past year, compared with 8% of men in the U.S. and 4% in Germany. In contrast, in Italy, men are just as likely (25%) as women (26%) to have provided personal care.

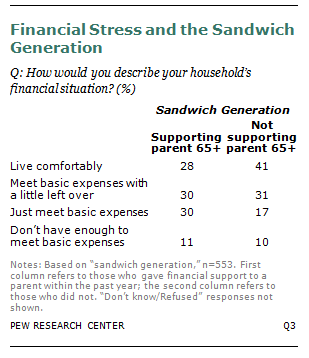

The Pew survey found that almost 33% of sandwich-generation adults were more likely to say they always feel rushed, while only 23% of other adults said this. However, the survey suggests that those who supported both parents and children reported being just as happy as those middle-aged adults who did not find themselves in the sandwich generation (Parker & Patten, 2013). Adults who are supporting both parents and children did report greater financial strain (see Figure 2). Only 28% reported that they were living comfortably versus 41% of those who were not also supporting their parents. Almost 33% were just making ends meet, compared with 17% of those who did not have the additional financial burden of aging parents.

Parenting in Later Life

Just because children grow up does not mean their family stops being a family; rather, the specific roles and expectations of its members change over time. One major change comes when a child reaches adulthood and moves away. When exactly children leave home varies greatly depending on societal norms and expectations, as well as on economic conditions such as employment opportunities and affordable housing options. Some parents may experience sadness when their adult children leave the home—a situation called an empty nest.

Empty nest. The empty nest or post-parental period refers to the time period when children are grown up and have left home (Dennerstein, Dudley & Guthrie, 2002). For most parents, this occurs during midlife. This time is recognized as a “normative event” as parents are aware that their children will become adults and eventually leave home (Mitchell & Lovegreen, 2009). The empty nest creates complex emotions, both positive and negative, for many parents. Some theorists suggest this is a time of role loss for parents; others suggest it is one of role strain relief (Bouchard, 2013).

The role loss hypothesis predicts that when people lose an important role in their lives, they experience a decrease in emotional well-being. It is from this perspective that the concept of the empty nest syndrome emerged, which refers to great emotional distress experienced by parents, typically mothers after their children have left home. The empty nest syndrome is linked to the absence of alternative roles for the parent in which they could establish their identity (Borland, 1982). In Bouchard’s (2013) review of the research, she found that few parents reported loneliness or a big sense of loss once all their children had left home.

In contrast, the role stress relief hypothesis suggests that the empty nest period should lead to more positive changes for parents, as the responsibility of raising children has been lifted. The role strain relief hypothesis was supported by many studies in Bouchard’s (2013) review. A consistent finding throughout the research literature is that raising children has a negative impact on the quality of marital relationships (Ahlborg et al., 2009; Bouchard, 2013). Most studies report that marital satisfaction often increases during the launching phase of the empty nest period and that this satisfaction endures long after the last child has left home (Gorchoff, John, & Helson, 2008).

However, most of the research on the post-parental period has been with American parents. A number of studies in China suggest that empty-nesters, especially in more rural areas of China, report greater loneliness and depression than their counterparts with children still at home (Wu et al., 2010). Family support for the elderly by their children is a cherished Chinese tradition (Wong & Leung, 2012). The fact that children move from rural communities to larger cities for education and employment may explain the more negative reaction of Chinese parents compared to American samples. The loss of an adult child in a rural region may mean a loss of family income and support for aging parents. Empty-nesters in urban regions of China did not report the same degree of distress (Su et al., 2012), suggesting that it is not so much the event of children leaving but the additional hardships this may place on aging parents.

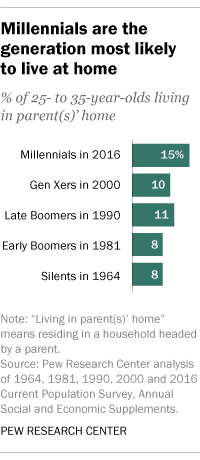

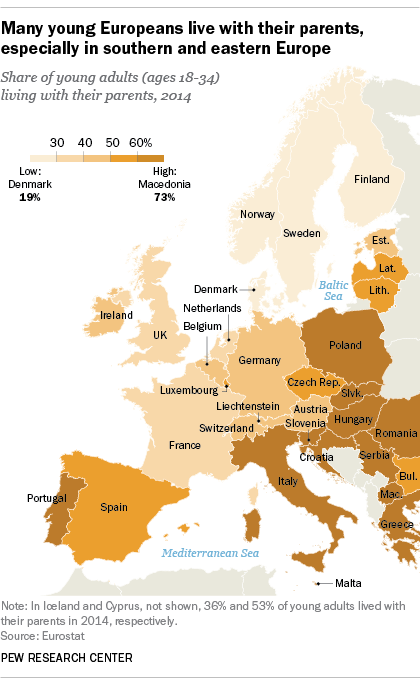

Boomerang Kids. Young adults are living with their parents for a longer duration and in greater numbers than previous generations. In addition to those in early adulthood who are not leaving the home of their parents, there are also boomerang kids, a term used to refer to young adults who return after having lived independently outside the home. The first Figure 3 shows the number of American young people 25-35 who were living at home based on their generation (Fry, 2017). The second Figure 8.15, with the European map, shows that more young adults 18-34 in Europe are also living with their parents (Desilver, 2016). Many of the same financial reasons that are influencing young people’s decisions to delay exit from the home of their parents are underlying their decisions to return home. In addition, to financial reasons, some boomerang kids are returning because of emotional distress, such as mental health issues (Sandberg-Thoma, Snyder, & Jang, 2015).

What is the effect on parents when their adult children return home? Certainly, there is considerable research that shows that the stress of raising children can have a negative impact on parents’ well-being and that when children leave home, many couples experience less stress and greater life satisfaction (see the section on the empty nest). Early research in the 1980s and 1990s supported the notion that boomerang children, along with those who were failing to exit the home, placed greater financial hardship on the parents, and the parents reported more negative perceptions of this living arrangement (Aquilino, 1991).

Recent surveys suggest that today’s parents are more tolerant of this, perhaps because this is becoming a more normative experience than in the past. Moreover, children who return are more likely to have had good relationships with their parents growing up, so there may be less stress between parents and their adult children who return (Sandberg-Thoma et al., 2015). Parents of young adults who have moved back home because of economic reasons report that they are just as satisfied with their lives as parents whose adult children are still living independently (Parker, 2012). Parker found that adult children aged 25 and older are more likely to contribute financially to the family or complete chores and other household duties. Parker also found that living in a multigenerational household may be acting as an economic safety net for young adults. In comparison to young adults who were living outside of the home, those living with their parents were less likely to be living in poverty (17% versus 10%).

Try It

Adult children typically maintain frequent contact with their parents, if for no other reason than money and advice. Attitudes toward one’s parents may become more accepting and forgiving, as parents are seen in a more objective way, as people with good points and bad. As adults, children can continue to be subjected to criticism, ridicule, and abuse at the hands of parents. How long are we “adult children”? For as long as our parents are living, we continue in the role of son or daughter. (I had a neighbor in her nineties who would tell me her “boys” were coming to see her this weekend. Her boys were in their 70s-but they were still her boys!) But after one’s parents are gone, the adult is no longer a child; as one 40-year-old man explained after the death of his father, “I’ll never be a kid again.”

So far, we have considered the impact that adult children who have returned home or have yet to leave the nest have on the lives of middle-aged parents. What about the effect on parents who have adult children dealing with personal problems, such as alcoholism, chronic health concerns, mental health issues, trouble with the law, poor social relationships, or academic or job-related problems, even if they are not living at home? The life course perspective proposes the idea of linked lives (Greenfield & Marks, 2006). The notion is that people in important relationships, such as children and parents, mutually influence each other’s developmental pathways. In previous chapters, you have read about the effects that parents have on their children’s development, but this relationship is bidirectional. The problems faced by children, even when those children are adults, influence the lives of their parents. Greenfield and Marks (2006) found in their study of middle-aged parents and their adult children those parents whose children were dealing with personal problems reported more negative affect, lower self-acceptance, poorer parent-child interactions, and more family relationship stress. The more problems the adult children were facing, the worse the lives and emotional health of their parents, with single parents faring the worst.

Abuse in Family Life

Abuse can occur in multiple forms and across all family relationships. Breiding, Basile, Smith, Black, & Mahendra (2015) define the forms of abuse as:

- Physical abuse: the use of intentional physical force to cause harm. Scratching, pushing, shoving, throwing, grabbing, biting, choking, shaking, slapping, punching, and hitting are common forms of physical abuse

- Sexual abuse: the act of forcing someone to participate in a sex act against his or her will. Such abuse is often referred to as sexual assault or rape. A marital relationship does not grant anyone the right to demand sex or sexual activity from anyone, even a spouse

- Psychological abuse: aggressive behavior that is intended to control someone else. Such abuse can include threats of physical or sexual abuse, manipulation, bullying, and stalking.

Abuse between partners is referred to as intimate partner violence; however, such abuse can also occur between a parent and child (child abuse), adult children and their aging parents (elder abuse), and even between siblings.

The most common form of abuse between parents and children is that of neglect. Neglect refers to a family’s failure to provide for a child’s basic physical, emotional, medical, or educational needs (DePanfilis, 2006). Harry Potter’s aunt and uncle, as well as Cinderella’s stepmother, could all be prosecuted for neglect in the real world.

Abuse is a complex issue, especially within families. There are many reasons people become abusers: poverty, stress, and substance abuse are common characteristics shared by abusers, although abuse can happen in any family. There are also many reasons adults stay in abusive relationships: (a) learned helplessness (the abused person believing he or she has no control over the situation); (b) the belief that the abuser can/will change; (c) shame, guilt, self-blame, and/or fear; and (d) economic dependence. All of these factors can play a role.

Children who experience abuse may “act out” or otherwise respond in a variety of unhealthy ways. These include acts of self-destruction, withdrawal, and aggression, as well as struggles with depression, anxiety, and academic performance. Researchers have found that abused children’s brains may produce higher levels of stress hormones. These hormones can lead to decreased brain development, lower stress thresholds, suppressed immune responses, and lifelong difficulties with learning and memory (Middlebrooks & Audage, 2008).

Committed Relationships in Middle Adulthood

It makes sense to consider the various types of relationships in our lives when trying to determine just how relationships impact our well-being. For example, would you expect a person to derive the same happiness from an ex-spouse as from a child or coworker? Among the most important relationships for most people is their long-time romantic partner. Most researchers begin their investigation of this topic by focusing on intimate relationships because they are the closest form of a social bond. Intimacy is more than just physical in nature; it also entails psychological closeness. Research findings suggest that having a single confidante—a person with whom you can be authentic and trust not to exploit your secrets and vulnerabilities—is more important to happiness than having a large social network (Taylor, 2010).

Another important aspect of relationships is the distinction between formal and informal. Formal relationships are those that are bound by the rules of politeness. In most cultures, for instance, young people treat older people with formal respect, avoiding profanity and slang when interacting with them. Similarly, workplace relationships tend to be more formal, as do relationships with new acquaintances. Formal connections are generally less relaxed because they require a bit more work, demanding that we exert more self-control. Contrast these connections with informal relationships—friends, lovers, siblings, or others with whom you can relax. We can express our true feelings and opinions in these informal relationships, using the language that comes most naturally to us and, generally, is more authentic. Because of this, it makes sense that more intimate relationships—those that are more comfortable and in which you can be more vulnerable—might be the most likely to translate to happiness.

Singlehood. According to a Pew Research study, 16 per 1,000 adults aged 45 to 54 and 7 per 1000 aged 55 and over have never-married in the U. S. (Wang & Parker, 2014). However, some of them may be living with a partner. In addition, some singles at midlife may be single through divorce or widowhood. DePaulo (2014) has challenged the idea that singles, especially the always single, fare worse emotionally and in health when compared to those married. DePaulo suggests there is a bias in how studies examine the benefits of marriage. Most studies focus on comparisons between married and not married, which do not include a separate comparison between those who are always single and those who are single because of divorce or widowhood. Her research has found that those who are married may be more satisfied with life than the divorced or widowed, but there is little difference between married and always single, especially when comparing those who are recently married with those who have been married for four or more years. It appears that once the initial blush of the honeymoon wears off, those who are wedded are no happier or healthier than those who remain single. This also suggests that it could be problematic for studies to consider the “married” category to be a homogeneous group.

Online Dating. Montenegro (2003) surveyed over 3,000 singles aged 40–69 and almost half of the participants reported their most important reason for dating was to have someone to talk to or do things with. Additionally, sexual fulfillment was also identified as an important goal for many. Alterovitz and Mendelsohn (2013) reviewed online personal ads for men and women over age 40 and found that romantic activities and sexual interests were mentioned at similar rates among the middle-aged and young-old age groups but less for the old-old age group.

Marriage

One of the most common ways that researchers often begin to investigate intimacy is by looking at marital status. The well-being of married people is compared to that of people who are single or have never been married. In other research, married people are compared to people who are divorced or widowed (Lucas & Dyrenforth, 2005). Researchers have found that the transition from singlehood to marriage brings about an increase in subjective well-being (Haring-Hidore, Stock, Okun, & Witter, 1985; Lucas, 2005; Williams, 2003). In fact, this finding is one of the strongest in social science research on personal relationships over the past quarter of a century.

As is usually the case, the situation is more complex than might initially appear. As a marriage progresses, there is some evidence for regression to a hedonic set-point—that is, most individuals have a set happiness point or level, and that both good and bad life events – marriage, bereavement, unemployment, births, and so on – have some effect for a period of time, but over many months, they will return to that set-point. One of the best studies in this area is that of Luhmann et al. (2012), who report a gradual decline in subjective well-being after a few years, especially in the component of affective well-being. Adverse events obviously have an effect on subjective well-being and happiness, and these effects can be stronger than the positive effects of being married in some cases (Lucas, 2005).

One way marriages vary is with regard to the reason the partners are married. Some marriages have intrinsic value: the partners are together because they enjoy, love, and value one another. Marriage is not thought of as a means to another end, instead it is regarded as an end in itself. These partners look for someone they are drawn to, and with whom they feel a close and intense relationship. Other marriages, called utilitarian marriages, are unions entered into primarily for practical reasons. For example, the marriage brings financial security, children, social approval, housekeeping, political favor, a good car, a great house, and so on.

There have been a few attempts to establish a typological framework for marriages. The best-known is that of Olson (1993), who referred to five typical kinds of marriage. Using a sample of 6,267 couples, Olson & Fowers (1993) identified eleven relationship domains that covered both areas related to relationship satisfaction and the more functional areas related to marriage. So, five of the eleven included areas such as marital satisfaction, communication, and, things like financial management, parenting, and egalitarian roles. Using these eleven areas, they came up with five kinds of marriage.

- Vitalized. Very high relationship quality. Tend to belong in a higher income bracket. Happy with their spouse across all areas—personality, communication, roles, and expectations.

- Harmonious relationships. These marriages have some areas of tension and disagreement but there is still broad agreement on major issues. Lack of agreement on parenting was the primary feature of this group, although the couples still scored highly on relationship quality.

- Traditional marriages. These marriages show much less emphasis on emotional closeness, but still score slightly above average on connection. There are high levels of compatibility in relation to parenting.

- Conflicted. These marriages accomplish functional goals such as parenting but are marked by a great deal of interpersonal disagreement. Communication and conflict resolution scores are extremely low.

- Devitalized. These marriages have low scores across all eleven areas—little interpersonal closeness and little agreement on family roles.

One aspect of this early study is the link between marital satisfaction and income/college education. The link between these factors is now commonplace in the literature. Olson & Fowers (1993) were one of the first studies to point to this link. The less well off are more prone to divorce, as are those with less college-level education. Income and college education are of course linked, and there is now increasing concern that marital dissolution and broader patterns of social inequality are now inextricably linked.

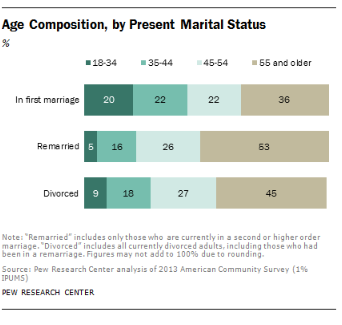

Trends seen in early adulthood also show up in relationships during middle adulthood, including declines in the rate of marriage, as more people are cohabitating, more are deciding to stay single, and more are getting married at a later age. As you can see in Figure 6, 48% of adults aged 45-54 are married, either in their first marriage (22%) or have remarried (26%). This makes marriage the most common relationship status for middle-aged adults in the United States.

Marital satisfaction has peaks and valleys during the course of the life cycle. Rates of happiness are highest in the years prior to the birth of the first child. It hits a low point with the coming of children. Marital satisfaction tends to increase for many couples in midlife as children leave home (Landsford et al., 2005). Not all researchers agree. They suggest that those who are unhappy with their marriage are likely to have gotten divorced by now, making the quality of marriages later in life only look more satisfactory (Umberson et al., 2005).

Although research frequently points to marriage being associated with higher rates of happiness, this does not guarantee that getting married will make you happy! The quality of one’s marriage matters greatly. When a person remains in a problematic marriage, it takes an emotional toll. Indeed, a large body of research shows that people’s overall life satisfaction is affected by their satisfaction with their marriage (Carr et al., 2008; Karney, 2001; Luhmann et al., 2012; Proulx et al., 2007). The lower a person’s self-reported level of marital quality, the more likely he or she is to report depression (Bookwala, 2012). In fact, longitudinal studies—those that follow the same people over a period of time—show that as marital quality declines, depressive symptoms increase (Fincham et al., 1997; Karney, 2001). Proulx et al. (2007) arrived at this same conclusion after a systematic review of 66 cross-sectional and 27 longitudinal studies.

What is it about bad marriages or bad relationships in general that takes such a toll on well-being? Research has pointed to the conflict between partners as a major factor leading to lower subjective well-being (Gere & Schimmack, 2011). This makes sense. Negative relationships are linked to ineffective social support (Reblin et al., 2010) and are a source of stress (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2007). In more extreme cases, physical and psychological abuse can be detrimental to well-being (Follingstad et al., 1990). Victims of abuse sometimes feel shame, lose their sense of self, and become less happy and prone to depression and anxiety (Arias & Pape, 1999). However, the unhappiness and dissatisfaction that occur in abusive relationships tend to dissipate once the relationships end. (Arriaga et al., 2013).

Divorce

Livingston (2014) found that 27% of adults aged 45 to 54 were divorced. Additionally, 57% of divorced adults were women. This reflects the fact that men are more likely to remarry than are women. Two-thirds of divorces are initiated by women (AARP, 2009). Most divorces take place within the first 5 to 10 years of marriage. This timeline reflects people’s initial attempts to salvage the relationship. After a few years of limited success, the couple may decide to end the marriage. It used to be that divorce after having been married for 20 or more years was rare, but in recent years the divorce rate among more long-term marriages has been increasing. Brown and Lin (2013) note that while the divorce rate in the U.S. has declined since the 1990s, the rate among those 50 and older has doubled.

Pursuing education decreases the risk of divorce. So, too, does waiting until we are older to marry. Likewise, if our parents are still married, we are less likely to divorce. Factors that increase our risk of divorce include having a child before marriage and living with multiple partners before marriage, known as serial cohabitation (cohabitation with one’s expected marital partner does not appear to have the same effect). Of course, societal and religious attitudes must also be taken into account. In societies that are more accepting of divorce, divorce rates tend to be higher. Likewise, in religions that are less accepting of divorce, divorce rates tend to be lower. See Lyngstad and Jalovaara (2010) for a more thorough discussion of divorce risk.

A “Gray Divorce Revolution”? In 2013 Brown and Lin referred to a “gray divorce revolution”. The figures certainly seem to support their contention. The rate of divorce had doubled for those aged 50-64 in the twenty years between 1990 and 2010. One in 10 persons who divorced in 1990 was over age 50, by 2010 it was over 1 in 4, accounting for some 25% of all divorces in the USA. Various explanations have been offered for this phenomenon. The “baby boomers” had divorced in large numbers in early adulthood, and a large number of remarriages within this group also ended in divorce. Remarriages are about 2.5 times more likely to end in divorce than first marriages. People are living longer and are no longer satisfied with relationships deemed insufficient to meet their emotional needs. The shift to companionate marriage in the latter half of the 20th century followed this segment of the population into midlife, with divorce rates diminishing or stabilizing for other segments of the population.

A survey by AARP (2009) found that men and women had diverse motivations for getting a divorce. Women reported concerns about the verbal and physical abusiveness of their partner (23%), drug/alcohol abuse (18%), and infidelity (17%). In contrast, men mentioned they had simply fallen out of love (17%), no longer shared interests or values (14%), and infidelity (14%). Both genders felt their marriage had been over long before the decision to divorce was made, with many of the middle-aged adults in the survey reporting that they stayed together because they were still raising children. Females also indicated that they remained in their marriage due to financial concerns, including the loss of health care (Sohn, 2015). However, only 1 in 4 adults regretted their decision to divorce.

The effects of divorce are varied. Overall, young adults struggle more with the consequences of divorce than do those in midlife, as they have a higher risk of depression or other signs of problems with psychological adjustment (Birditt & Antonucci, 2013). Divorce at midlife is more stressful for women. In the AARP (2009) survey, 44% of middle-aged women mentioned financial problems after divorcing their spouse; in comparison, only 11% of men reported such difficulties. However, a number of women who divorce in midlife report that they felt a great release from their day-to-day sense of unhappiness. Hetherington and Kelly (2002) found that among the divorce enhancers, those who had used the experience to better themselves and seek more productive intimate relationships, and the competent loners, those who used their divorce experience to grow emotionally, but who chose to stay single, the overwhelming majority were women.

Dating Post-Divorce. Most divorced adults have dated by one year after filing for divorce (Anderson et al., 2004; Anderson & Greene, 2011). One in four recent filers report having been in or were currently in a serious relationship, and over half were in a serious relationship by one year after filing for divorce. Not surprisingly, younger adults were more likely to be dating than middle-aged or older adults, no doubt due to the larger pool of potential partners from which they could draw. Of course, these relationships will not all end in marriage. Teachman (2008) found that more than two-thirds of women under the age of 45 had cohabited with a partner between their first and second marriages.

Dating for adults with children can be more of a challenge. Courtships are shorter in remarriage than in first marriages. When couples are “dating”, there is less going out and more time spent in activities at home or with the children. So, the couple gets less time together to focus on their relationship. Anxiety or memories of past relationships can also get in the way. As one Talmudic scholar suggests, “When a divorced man marries a divorced woman, four go to bed” (Secombe & Warner, 2004).

Post-divorce parents gatekeep, that is, they regulate the flow of information about their new romantic partner to their children in an attempt to balance their own needs for romance with consideration regarding the needs and reactions of their children. Anderson et al. (2004) found that almost half (47%) of dating parents gradually introduce their children to their dating partner, giving both their romantic partner and children time to adjust and get to know each other. Many parents who use this approach do so to protect their children from having to keep meeting someone new until it becomes clear that this relationship might be a lasting one. It might also help if the adult relationship is on firmer ground so it can weather any initial pushback from children when it is revealed. Forty percent of people are open and transparent with their children about the new relationship right from the outset. Thirteen percent do not reveal the relationship until it is clear that cohabitation and or remarriage is likely. Anderson and colleagues suggest that practical matters influence which gatekeeping method parents may use. Parents may be able to successfully shield their children from a parade of partners if there is reliable childcare available. The age and temperament of the child, along with concerns about the reaction of the ex-spouse, may also influence when parents reveal their romantic relationships to their children.

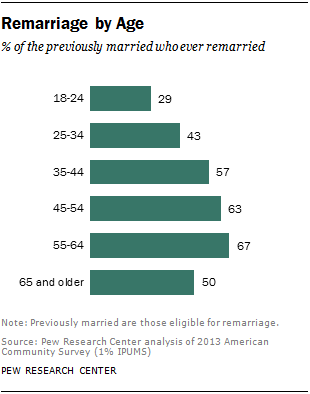

Rates of re-marriage. The rate for remarriage, like the rate for marriage, has been declining overall. In 2013 the remarriage rate was approximately 28 per 1,000 adults 18 and older. This represents a 44% decline since 1990 and a 16% decline since 2008 (Payne, 2015). Brown and Lin (2013) found that the rate of remarriage dropped more for younger adults than middle-aged and older adults, and Livingston (2014) found that as we age, we are more likely to have remarried (see Figure 7). This is not surprising as it takes some time to marry, divorce, and then find someone else to marry. However, Livingston found that unlike those younger than 55, those 55 and up are remarrying at a higher rate than in the past. In 2013, 67% of adults 55-64 and 50% of adults 65 and older had remarried, up from 55% and 34% in 1960, respectively.

Men have a higher rate of remarriage in every age group, starting at age 25 (Payne, 2015). Livingston (2014) reported that in 2013, 64% of divorced or widowed men, compared with 52% of divorced or widowed women, had remarried. However, this gender gap has narrowed over time. Even though more men still remarry, they are remarrying at a slower rate. In contrast, women are remarrying today more than they did in 1980. This gender gap has closed mostly among young and middle-aged adults but still persists among those 65 and older.

In 2012, Whites who were previously married were more likely to remarry than other racial and ethnic groups (Livingston, 2014). Moreover, the rate of remarriage has increased among Whites, while the rate of remarriage has declined for other racial and ethnic groups. This increase is driven by White women, whose rate of remarriage has increased, while the rate for White males has declined.

The success of Re-marriage. Research is mixed as to the happiness and success of remarriages. While some remarriages are more successful, especially if the divorce motivated the adult to engage in self-improvement and personal growth (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002), a number of divorced adults end up in very similar marriages the second or third time around (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). Remarriages have challenges not found in first marriages, and they can create additional stress in the marital relationship.

There can also be a general lack of clarity in family roles and expectations when trying to incorporate new kin into the family structure. Even determining the appropriate terms for these kin, along with their roles, can be a challenge. Partners may have to carefully navigate their roles when dealing with their partners’ children. All of this may lead to greater dissatisfaction and even resentment among family members. Even though remarried couples tend to have more realistic expectations for marriage, they tend to be less willing to stay in unhappy situations. The rate of divorce among remarriages is higher than among first marriages (Payne, 2015), which can add additional burdens, especially when children are involved.

Children’s Influence on Re-partnering. Do children affect whether a parent remarries? Goldscheider and Sassler (2006) found children residing with their mothers reduces the mothers’ likelihood of marriage, only with respect to marrying a man without children. Further, having children in the home appears to increase single men’s likelihood of marrying a woman with children (Stewart, Manning, & Smock, 2003). There is also some evidence that individuals who participated in a stepfamily while growing up may feel better prepared for stepfamily living as adults. Goldscheider and Kaufman (2006) found that having experienced family divorce as a child is associated with a greater willingness to marry a partner with children.

When children are present after divorce, one of the challenges the adults encounter is how much influence the child will have in the selection of a new partner. Greene, Anderson, Hetherington, Forgatch, and DeGarmo (2003) identified two types of parents. The child-focused parent allows the child’s views, reactions, and needs to influence the re-partnering. In contrast, the adult-focused parent expects that their child can adapt and should accommodate parental wishes. Anderson and Greene (2011) found that divorced custodial mothers identified as more adult-focused tended to be older, more educated, employed, and more likely to have been married longer. Additionally, adult-focused mothers reported having less rapport with their children, spent less time in joint activities with their children, and the child reported lower rapport with their mothers. Lastly, when the child and partner were resisting one another, adult-focused mothers responded more to the concerns of the partner, while child-focused mothers responded more to the concerns of the child. Understanding the implications of these two differing perspectives can assist parents in their attempts to re-partner.

Blended Families

Most academic research on reconstituted or blended families focuses on younger adults and the kind of difficulties that ensue when trying to blend children raised by a different spouse/partner and one or more adults with perhaps different views or experiences on how this might be accomplished. All sorts of issues can arise conflicted loyalties, different attitudes to discipline, role ambiguity, and the simple fact of a far-reaching change easily perceived as a disruption on the part of a child. Given the rise of the gray divorce, it is increasingly the case that this age group will encounter later age or adult children (sometimes called the “boomerang generation”) in the house of their new partners. Such encounters are even more likely given the rise of the so-called “silver surfer” utilizing online dating sites and the fact that an increasing number of adult children continue to live at home, given the increased cost of housing.

There has not been substantial research on recoupling and blended families in later life, but Papernow (2018) notes that all of the factors normally in play with younger children can be just as present and even exacerbated by the fact that previous relationships have had an even longer time to grow and solidify. In addition, stepfamilies formed in later life may have very difficult and complicated decisions to make about estate planning and elder care, as well as navigating daily life together, as an increasing number of young adults live at home (“grown but not gone”). Papernow lists five challenges for later-life stepfamilies:

- Stepparents are stuck as outsiders, while parents are the insiders in their relationships with their families.

- Stepchildren struggle with the change, even as adults, as they navigate new dynamics in family gatherings, status, and loyalty issues

- Parenting and discipline issues polarize parents and stepparents. In general, stepparents want more discipline and are viewed as harsher, while parents want more understanding and are viewed as pushovers. There are often disagreements about how much support (financial, physical, and emotional) to give older children.

- Stepfamilies must build a new family culture even after at least two established family cultures have come together.

- Ex-spouses are still part of a stepfamily, and children, even adult children, are worse off when they are involved in the conflict between their parents’ ex-spouses.

The Family Life Cycle

To better understand patterns of family life and changes in roles and expectations as family ages, researchers have theorized about typical stages of family life. Read more about the family life cycle in the following interactive activity.

Try It

Grandparents

In addition to maintaining relationships with their children and aging parents, many people in middle adulthood take on yet another role, becoming a grandparent. The role of grandparents varies around the world. In multigenerational households, grandparents may play a greater role in the day-to-day activities of their grandchildren. While this family dynamic is more common in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, it has been on the increase in the U.S. (Pew Research Center, 2010). Around the world, even when not cohabitating with their children and grandchildren, grandparents are usually a major source of support for new parents and young families.

The degree of grandparent involvement depends on the proximity of the grandparents’ home to the grandchildren. In developed nations, greater societal mobility means that many grandparents live long distances from their grandchildren. Technology has brought grandparents and their more distant grandchildren together. Sorenson and Cooper (2010) found that many of the grandfathers they interviewed would text, email, or Skype with their grandchildren in order to stay in touch.

Cherlin and Furstenberg (1986) described three styles of grandparents.

- Remote: Thirty percent of grandparents rarely see their grandchildren. They usually live far away from their grandchildren but may also have a distant relationship. Contact is typically made on special occasions, such as holidays or birthdays.

- Companionate: Fifty-five percent of grandparents were described as “companionate”. These grandparents do things with the grandchild but have little authority or control over them. They prefer to spend time with them without interfering in parenting. They are more like friends to their grandchildren.

- Involved: Fifteen percent of grandparents were described as “involved”. These grandparents take a very active role in their grandchild’s life. The children might even live with their grandparents. The involved grandparent is one who has frequent contact with and authority over the grandchild. Grandmothers, more so than grandfathers, play this role. In contrast, more grandfathers than grandmothers saw their role as family historians and family advisors (Neugarten & Weinstein, 1964). T

Bengtson (2001) suggests that grandparents adopt different styles with different grandchildren and may change styles over time as circumstances in the family change. Today, more grandparents are the sole care providers for grandchildren or may step in at times of crisis.

Early research on grandparents has routinely focused on grandmothers, with grandfathers often becoming invisible members of the family (Sorensen & Cooper, 2010). Yet, grandfathers stress the importance of their relationships with their grandchildren as strongly as do grandmothers (Waldrop et al., 1999). For some men, this may provide them with the opportunity to engage in activities that their occupations, as well as their generation’s views of fatherhood and masculinity, kept them from engaging in with their own children (Sorensen & Cooper, 2010). Many of the grandfathers in Sorenson and Cooper’s study felt that being a grandfather was easier and a lot more enjoyable. Even among grandfathers who took on a more involved role, there was still a greater sense that they could be more light-hearted and flexible in their interactions with their grandchildren. Many grandfathers reported that they were more openly affectionate with their grandchildren than they had been with their own children.

Friendships in Middle Adulthood

Adults of all ages who reported having a confidante or close friend with whom they could share personal feelings and concerns believed these friends contributed to a sense of belonging, security, and overall well-being (Dunér & Nordstrom, 2007). Having a close friend is a factor in significantly lower odds of psychiatric morbidity, including depression and anxiety (Harrison, Barrow, Gask, & Creed, 1999; Newton et al., 2008). The availability of a close friend has also been shown to lessen the adverse effects of stress on health (Kouzis & Eaton, 1998; Hawkley et al., 2008; Tower & Kasl, 1995). Additionally, poor social connectedness in adulthood is associated with a larger risk of premature mortality than cigarette smoking, obesity, and excessive alcohol use (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, & Layton, 2010).

Female friendships and social support networks at midlife contribute significantly to a woman’s feeling of life satisfaction and well-being (Borzumato-Gainey et al., 2009). Degges-White and Myers (2006) found that women who have supportive people in their lives experience greater life satisfaction than those who live a more solitary life. A friendship network or the presence of a confidante have both been found to be important to women’s mental health (Baruch & Brooks-Gunn, 1984). Unfortunately, with numerous caretaking responsibilities at home, it may be difficult for women to find time and energy to enhance the friendships that would provide an increased sense of life satisfaction (Borzumato-Gainey et al., 2009). Emslie et al. (2013) found that for men in midlife, the shared consumption of alcohol was important to creating and maintaining male friends. Drinking with friends was justified as a way for men to talk to each other, provide social support, relax, and improve mood. Although the social support provided when men drink together can be helpful, the role of alcohol in male friendships can lead to health-damaging behavior from excessive drinking.

The importance of social relationships begins in early adulthood by laying down a foundation for strong social connectedness and facilitating comfort with intimacy (Erikson, 1959). To determine the impact of the quantity and quality of social relationships in young adulthood on middle adulthood, Carmichael et al. (2015) assessed individuals at age 50 on measures of social connection (types of relationships and friendship quality) and psychological outcomes (loneliness, depression, psychological well-being). Results indicated that the quantity of social interactions at age 20 and the quality, but not quantity, of social interaction at age 30 predicted midlife social interactions. Those individuals who had high levels of social information seeking (quantity) at age 20, followed by fewer social relationships but greater emotional closeness (quality), ended up showing the most positive psychosocial adjustment at midlife.

Happy, Healthy Families

Our families play a crucial role in our overall development and happiness. They can support and validate us, but they can also criticize and burden us. For better or worse, we all have a family. In closing, here are strategies you can use to increase the happiness of your family:

- Teach morality—fostering a sense of moral development in children can promote well-being (Damon, 2004).

- Savor the good—celebrate each other’s successes (Gable et al., 2006).

- Use the extended family network—family members of all ages, including older siblings and grandparents, who can act as caregivers, can promote family well-being (Armstrong et al., 2005).

- Create family identity by sharing inside jokes and fond memories and framing the family story (McAdams, 1993).

- Forgive—Don’t hold grudges against one another (McCullough et al., 1997).

Women in Midlife

In Western society, aging for women is much more stressful than for men, as society emphasizes youthful beauty and attractiveness (Slevin, 2010). The description that aging men are viewed as “distinguished” and aging women are viewed as “old” is referred to as the double standard of aging (Teuscher & Teuscher, (2006). Since women have traditionally been valued for their reproductive capabilities, they may be considered old once they are postmenopausal. In contrast, men have traditionally been valued for their achievements, competence and power, and therefore are not considered old until they are physically unable to work (Carroll, 2016).

Consequently, women experience more fear, anxiety, and concern about their identity as they age and may feel pressure to prove themselves as productive and valuable members of society (Bromberger et al., 2013).

Attitudes about aging, however, do vary by race, culture, and sexual orientation. In some cultures, aging women gain greater social status. For example, as Asian women age they attain greater respect and have greater authority in the household (Fung, 2013). Compared to white women, Black and Latina women possess fewer stereotypes about aging (Schuler et al., 2008). Lesbians are also more positive about aging and looking older than heterosexuals (Slevin, 2010). The impact of media certainly plays a role in how women view aging by selling anti-aging products and supporting cosmetic surgeries to look younger (Gilleard & Higgs, 2000).

Religion and Spirituality

Grzywacz and Keyes (2004) found that in addition to personal health behaviors, such as regular exercise, healthy weight, and not smoking, social behaviors, including involvement in religious-related activities, have been shown to be positively related to optimal health. However, it is not only those who are involved in a specific religion that benefits but so too do those identified as being spiritual. According to Greenfield, Vaillant, and Marks (2009), religiosity refers to engaging with a formal religious group’s doctrines, values, traditions, and co-members. In contrast, spirituality refers to an individual’s intrapsychic sense of connection with something transcendent (that which exists apart from and not limited by the material universe) and the subsequent feelings of awe, gratitude, compassion, and forgiveness. Research has demonstrated a strong relationship between spirituality and psychological well-being, irrespective of an individual’s religious participation (Vaillant, 2008). Additionally, Sawatzky, Ratner, & Chiu (2005) found that spirituality was related to a higher quality of life for both individuals and societies.

Based on reports from the 2005 National Survey of Midlife in the United States, Greenfield et al (2009) found that higher levels of spirituality were associated with lower levels of negative affect and higher levels of positive affect, personal growth, purpose in life, positive relationships with others, self-acceptance, environmental mastery, and autonomy. In contrast, formal religious participation was only associated with higher levels of purpose in life and personal growth among just older adults and lower levels of autonomy. In summary, it appears that formal religious participation and spirituality relate differently to an individual’s overall psychological well-being.

Religion and Age. Older individuals identify religion/spirituality as being more important in their lives than those younger (Beit-Hallahmi & Argyle, 1998). This age difference has been explained by several factors, including that religion and spirituality assist older individuals in coping with age-related losses, provide opportunities for socialization and social support in later life, and demonstrate a cohort effect in that older individuals were socialized more to be religious and spiritual than those younger (Greenfield et al., 2009).

Religion and Gender. In the United States, women report identifying as being more religious and spiritual than men do (De Vaus & McAllister, 1987). According to the Pew Research Center (2016), women in the United States are more likely to say religion is very important in their lives than men (60% vs. 47%). American women also are more likely than American men to say they pray daily (64% vs. 47%) and attend religious services at least once a week (40% vs. 32%). Theories to explain this gender difference include that women may benefit more from the social-relational aspects of religion/spirituality because social relationships more strongly influence women’s mental health. Additionally, women have been socialized to internalize the behaviors linked with religious values, such as cooperation and nurturance, more than males (De Vaus & McAllister, 1987).

Religion Worldwide. To measure the religious beliefs and practices of men and women around the world, the Pew Research Center (2016) conducted surveys of the general population in 84 countries between 2008 and 2015. Overall, an estimated 83% of women worldwide identified with a religion compared with 80% of men. This equaled 97 million

more women than men identifying with a religion. There were no countries in which men were more religious than women by 2 percentage points or more. Among Christians, women reported higher rates of weekly church attendance and higher rates of daily prayer. In contrast, Muslim women and Muslim men showed similar levels of religiousness, except frequency of attendance at worship services. Because of religious norms, Muslim men worshiped at a mosque more often than Muslim women. Similarly, Jewish men attended a synagogue more often than Jewish women. In Orthodox Judaism, communal worship services cannot take place unless a minyan, or quorum of at least 10 Jewish men, is present, thus ensuring that men will have high rates of attendance. Only in Israel, where roughly 22% of all Jewish adults self-identify as Orthodox, did a higher percentage of men than women report engaging in daily prayer.

Conclusion

At the beginning of this section, we referred to the physical, psychological, and social aspects of middle adulthood. These have ranged from minor physiological changes to the way that knowledge of our own mortality may influence how we behave and feel during this part of the lifespan. The central theme might be identified as that of connection—the way that the body and mind are connected, how one can affect the other, exemplified by the way that physical mobility can impact cerebral acuity. In addition, we have learned that we are more selective in regard to the interpersonal connection as we age. The positive aspects of relationships, work, and the family assume ever greater importance. Hope is ever-present, but these sorts of positive and fulfilling connections cannot be postponed indefinitely. Freud believed that civilization was only possible if humans could be induced, or trained, to defer immediate gratification. That was what the process of primary childhood socialization was about. Perhaps middle adulthood demands that we unlearn this, if only partially. At this stage of the life course, it is now or never. Time is finite, and there is none left for indefinite postponement. This is what modern developmental theory has come to understand as mortality salience.

Developmental perspectives have tended to view intimacy and familial relationships as a universal need and function. It has largely left their transformation by divorce, cohabitation, and so forth to the sociologists. However, there is now a clearer understanding of the way that structural economic and social change have impacted family structures, often in those least able to resist the disruptive effects of social inequality (Cherlin, 2014). Income and education levels play as large a part in all of this as lifestyle choices and selectivity. We can only hope that advances in medical science can lead to a greater quality of life at this stage of the life course and that they are made widely available.

Additional Resources

Websites

- Seattle Longitudinal Study (SLS) of adult cognition

- This study began in 1956 and is one of the most influential perspectives on cognition during middle adulthood.

- Midlife in the United States Studies (MIDUS)

- This longitudinal study began in 1994. The MIDUS data supports the view that this period of life is something of a trade-off, with some cognitive and physical decreases of varying degrees.

Videos

- Aging and cognitive abilities | Khan Academy

- Learn about how cognitive abilities change as we age.

- Rethinking Infidelity…. a Talk for Anyone Who has ever Loved

- Infidelity is the ultimate betrayal. But does it have to be? Relationship therapist Esther Perel examines why people cheat and unpacks why affairs are so traumatic: because they threaten our emotional security. In infidelity, she sees something unexpected — an expression of longing and loss. A must-watch for anyone who has ever cheated or been cheated on, or who simply wants a new framework for understanding relationships.

- Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse | The Gottman Institute

- Certain negative communication styles are so lethal to a relationship that Dr. John Gottman calls them the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. If the behavior isn’t changed, they predict relationship failure with over 90% accuracy.

- A Brief History of Divorce: TedEd

- Formally or informally, human societies across place and time have made rules to bind and dissolve couples. The stakes of who can obtain a divorce and why have always been high. Divorce is a battlefield for some of society’s most urgent issues, including the roles of church and state, individual rights, and women’s rights. Rod Phillips digs into the complicated history of divorce.

- 100 Years of Beauty: Aging

- If you had a crystal ball and could gaze into the future, how would you feel seeing the love of your life as a 90-year-old? Cut offered a young couple about to say their vows the unique chance to do just that by aging them over 60 years with incredibly life-like makeup and prosthetics. We dare you not to tear up as they fall in love again and again.

Attributions

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Some selections were adapted from The Noba Project

References

AARP. (2009). The divorce experience: A study of divorce at midlife and beyond. Washington, DC: AARP

Ahlborg, T., Misvaer, N., & Möller, A. (2009). Perception of marital quality by parents with small children: A follow-up study when the firstborn is 4 years old. Journal of Family Nursing, 15, 237–263.

Alterovitz, S. S., & Mendelsohn, G. A. (2013). Relationship goals of middle-aged, young-old, and old-old Internet daters: An analysis of online personal ads. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 159–165.

Anderson, E. R., & Greene, S. M. (2011). “My child and I are a package deal”: Balancing adult and child concerns in repartnering after divorce. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(5), 741-750.

Anderson, E.R., Greene, S.M., Walker, L., Malerba, C.A., Forgatch, M.S., & DeGarmo, D.S. (2004). Ready to take a chance again: Transitions into dating among divorced parents. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 40, 61-75.

Aquilino, W. (1991). Predicting parents’ experiences with coresidence adult children. Journal of Family Issues, 12(3), 323-342.

Arai, Y., Sugiura, M., Miura, H., Washio, M., & Kudo, K. (2000). Undue concern for other’s opinions deters caregivers of impaired elderly from using public services in rural Japan. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(10), 961-968.

Beach, S. R., Schulz, R., Yee, J. L., & Jackson, S. (2000). Negative and positive health effects of caring for a disabled spouse: Longitudinal findings from the caregiver health effects study. Psychology and Aging, 15(2), 259-271.

Beit-Hallahmi, B., & Argyle, M. (1998). Religious behavior, belief, and experience. New York: Routledge.

Bengtson, V. L. (2001). Families, intergenerational relationships, and kinkeeping in midlife. In N. M. Putney (Author) & M. E. Lachman (Ed.), Handbook of midlife development (pp. 528-579). New York: Wiley.

Birditt, K. S., & Antonucci, T.C. (2012). Till death do us part: Contexts and implications of marriage, divorce, and remarriage across adulthood. Research in Human Development, 9(2), 103-105.

Borland, D. C. (1982). A cohort analysis approach to the empty-nest syndrome among three ethnic groups of women: A theoretical position. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 44, 117–129.

Bouchard, G. (2013). How do parents reaction when their children leave home: An integrative review. Journal of Adult Development, 21, 69-79.

Bromberger, J. T., Kravitz, H. M., & Chang, Y. (2013). Does risk for anxiety increase during the menopausal transition? Study of women’s health across the nation (SWAN). Menopause, 20(5), 488-495.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1989). Ecological systems theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Annals of Child Development, Vol. 6 (pp. 187–251). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Brown, S. L., & Lin, I. (2013). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle aged and older adults 1990-2010. National Center for Family & Marriage Research Working Paper Series. Bowling Green State University. https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and- sciences/NCFMR/ documents/Lin/The-Gray-Divorce.pdf

Bumpass, L. L. (1990). What’s happening to the family? Interactions between demographic and institutional change. Demography, 27(4), 483–498.

Carmichael, C. L., Reis, H. T., & Duberstein, P. R. (2015). In your 20s it’s quantity, in your 30s it’s quality: The prognostic value of social activity across 30 years of adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 30(1), 95-105.

Carroll, J. L. (2016). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Cherlin, A. J., & Furstenberg, F. F. (1986). The new American grandparent: A place in the family, a life apart. New York: Basic Books.

Cohen, P. (2013). Marriage is declining globally. Can you say that? Retrieved from https://familyinequality.wordpress.com/2013/06/12/marriage-is-declining/

Conger, R. D., & Conger, K. J. (2002). Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 361–373.

Cooke, L. P. (2010). The politics of housework. In J. Treas & S.Drobnic (Eds.), Dividing the domestic: Men, women, and household work in cross-national perspective (pp. 59-78). Standford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Crowley, K., Callanan, M. A., Tenenbaum, H. R., & Allen, E. (2001). Parents explain more often to boys than to girls during shared scientific thinking. Psychological Science, 12, 258–261.

Dennerstein, L., Dudley, E., & Guthrie, J. (2002). Empty nest or revolving door? A prospective study of women’s quality of life in midlife during the phase of children leaving and re-entering the home. Psychological Medicine, 32, 545–550.

DePaulo, B. (2014). A singles studies perspective on mount marriage. Psychological Inquiry, 25(1), 64-68.

Desai, S., & Andrist, L. (2010). Gender scripts and age at marriage in India. Demography, 47, 667-687.

Desilver, D. (2016). In the U. S. and abroad, more young adults are living with their parents. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/05/24/in-the-u-s-and-abroad-more-young-adults-are-living-with-their-parents/

De Vaus, D. & McAllister, I. (1987). Gender differences in religion: A test of the structural location theory. American Sociological Review, 52, 472-481.

Eastley, R., & Wilcock, G. K. (1997). Prevalence and correlates of aggressive behaviors occurring in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 12, 484-487.

Emslie, C., Hunt, K., & Lyons, A. (2013. The role of alcohol in forging and maintaining friendships amongst Scottish men in midlife. Health Psychology, 32(10, 33-41.

Erikson, E. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. (1959). Identity and the life cycle. New York: Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. (1982). The life cycle completed. New York: Norton & Company.

Fehr, B. (2008). Friendship formation. In S. Sprecher, A. Wenzel, & J. Harvey (Eds.), Handbook of Relationship Initiation (pp. 29–54). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Fung, H. H. (2013). Aging in culture. Gerontologist, 53(3), 369-377.

Gibbons, C., Creese, J., Tran, M., Brazil, K., Chambers, L., Weaver, B., & Bedard, M. (2014). The psychological and health consequences of caring for a spouse with dementia: A critical comparison of husbands and wives. Journal of Women & Aging, 26, 3-21.

Gilleard, C., & Higgs, P. (2000). Cultures of aging: Self, citizen and the body. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Publishers.

Goldscheider, F., & Kaufman, G. (2006). Willingness to stepparent: Attitudes about partners who already have children. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 1415 – 1436.

Goldscheider, F., & Sassler, S. (2006). Creating stepfamilies: Integrating children into the study of union formation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 275 – 291.

Gonzales, N. A., Coxe, S., Roosa, M. W., White, R. M. B., Knight, G. P., Zeiders, K. H., & Saenz, D. (2011). Economic hardship, neighborhood context, and parenting: Prospective effects on Mexican-American adolescent’s mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 98–113.

Gorchoff, S. M., John, O. P., & Helson, R. (2008). Contextualizing change in marital satisfaction during middle age. Psychological Science, 19, 1194–1200.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (2000). The timing of divorce: Predicting when a couple will divorce over a 14-year period. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 62, 737-745.

Greene, S. M., Anderson, E. R., Hetherington, E., Forgtch, M. S., & DeGarmo, D. S. (2003). Risk and resilience after divorce. In F. Walsh (Ed.), Normal family processes: Growing diversity and complexity (3rd ed., pp. 96-120). New York: Guilford Press.

Greenfield, E. A., & Marks, N. F. (2006). Linked lives: Adult children’s problems and their parents’ psychological and relational well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 442-454.

Greenfield, E. A., Vaillant, G. E., & Marks, N. F. (2009). Do formal religious participation and spiritual perceptions have independent linkages with diverse dimensions of psychological well-being? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50, 196-212.

Grzywacz, J. G. & Keyes, C. L. (2004). Toward health promotion: Physical and social behaviors in complete health. Journal of Health Behavior, 28(2), 99-111.

Ha, J., Hong, J., Seltzer, M. M., & Greenberg, J. S. (2008). Age and gender differences in the well-being of midlife and aging parents with children with mental health or developmental problems: Report of a national study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49, 301-316.

Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., & Ventura, S. J. (2011). Births: Preliminary data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports, 60(2). Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Hawkley, L. C., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Masi, C. M., Thisted, R. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago health, aging, and marital status transitions and health outcomes social relations study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63, 375–384.

Hayslip Jr., B., Henderson, C. E., & Shore, R. J. (2003). The Structure of Grandparental Role Meaning. Journal of Adult Development, 10(1), 1-13.

Hetherington, E. M. & Kelly, J. (2002). For better or worse: Divorce reconsidered. New York, NY: Norton.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316.

Institute of Medicine. (2015). Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near end of life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kang, S. W., & Marks, N. F. (2014). Parental caregiving for a child with special needs, marital strain, and physical health: Evidence from National Survey of Midlife in the U.S. 2005. Contemporary Perspectives in Family Research, 8A, 183-209.

Kerr, D. C. R., Capaldi, D. M., Pears, K. C., & Owen, L. D. (2009). A prospective three generational study of fathers’ constructive parenting: Influences from family of origin, adolescent adjustment, and offspring temperament. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1257–1275.

Krause, N. A., Herzog, R., & Baker, E. (1992). Providing support to others and well-being in later life. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 47, P300-311.

Lachman, M. E. (2004). Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 305-331.

Landsford, J. E., Antonucci, T.C., Akiyama, H., & Takahashi, K. (2005). A quantitative and qualitative approach to social relationships and well-being in the United States and Japan. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 36, 1-22.

Lesthaeghe, R. J., & Surkyn, J. (1988). Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review 14(1), 1–45.

Livingston, G. (2014). Four in ten couples are saying I do again. In Chapter 3. The differing demographic profiles of first-time marries, remarried and divorced adults. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/11/14/chapter-3-the-differing-demographic-profiles-of-first-time-married-remarried-and-divorced-adults/

Lucas, R. E. & Donnellan, A. B. (2011). Personality development across the life span: Longitudinal analyses with a national sample from Germany. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 847–861

Martinez, G., Daniels, K., & Chandra, A. (2012). Fertility of men and women aged 15-44 years in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006-2010. National Health Statistics Reports, 51(April). Hyattsville, MD: U.S., Department of Health and Human Services.

Metlife. (2011). Metlife study of caregiving costs to working caregivers: Double jeopardy for baby boomers caring for their parents. Retrieved from http://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/mmi-caregiving-costs-working-caregivers.pdf

Mitchell, B. A., & Lovegreen, L. D. (2009). The empty nest syndrome in midlife families: A multimethod exploration of parental gender differences and cultural dynamics. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 1651–1670.

Montenegro, X. P. (2003). Lifestyles, dating, and romance: A study of midlife singles. Washington, DC: AARP.

National Alliance for Caregiving. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015. Retrieved from http://www.caregiving.org/caregiving2015.

Neugarten, B. L., & Weinstein, K. K. (1964). The changing American grandparent. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 26, 199–204.

Newton, T., Buckley, A., Zurlage, M., Mitchell, C., Shaw, A., & Woodruff-Borden, J. (2008). Lack of a close confidant: Prevalence and correlates in a medically underserved primary care sample. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 13, 185–192.

Papernow, P. L. (1993). Becoming a stepfamily: Patterns of development in remarried families. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Parker, K. & Patten, E. (2013). The sandwich generation: Rising financial burdens for middle-aged Americans. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/01/30/the-sandwich-generation/

Payne, K. K. (2015). The remarriage rate: Geographic variation, 2013. National Center for Family & Marriage Research. Retrieved from http://bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/payne-remarriage-rate-fp-15-08.html

Pew Research Center. (2010). The return of the multi-generational family household. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/03/18/the-return-of-the-multi-generational-family-household/

Pew Research Center. (2010a). How the great recession has changed life in America. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/06/30/how-the-great-recession-has-changed-life-in-america/

Pew Research Center. (2010b). Section 5: Generations and the great recession. Retrieved from http://www.people-press.org/2011/11/03/section-5-generations-and-the-great-recession/

Pew Research Center. (2015). Caring for aging parents. Family support in graying societies. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/05/21/4-caring-for-aging-parents/

Pew Research Center. (2016). The Gender gap in religion around the world. http://www.pewforum.org/2016/03/22/the-gender-gap-in-religion-around-the-world/

Pew Research Center. (2016). The Gender gap in religion around the world. http://www.pewforum.org/2016/03/22/the-gender-gap-in-religion-around-the-world/

Prinzie, P., Stams, G. J., Dekovic, M., Reijntjes, A. H., & Belsky, J. (2009). The relations between parents’ Big Five personality factors and parenting: A meta-review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 351–362.

Proulx, C. M., Helms, H. M., & Buehler, C. (2007). Marital Quality and Personal Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3), 576–593

Saginak, K. A., & Saginak, M. A. (2005). Balancing work and family: Equity, gender, and marital satisfaction. Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 13, 162-166.

Sandberg-Thoma, S. E., Synder, A. R., & Jang, B. J. (2015). Exiting and returning to the parental home for boomerang kids. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 806-818.

Sawatzky, R., Ratner, P. A., & Chiu, L. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between spirituality and quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 72, 153-188.

Schuler, P., Vinci, D., Isosaari, R., Philipp, S., Todorovich, J., Roy, J., & Evans, R. (2008). Body-shape perceptions and body mass index of older African American and European American women. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 23(3), 255-264.

Schulz, R., Newsom, J., Mittelmark, M., Burton, L., Hirsch, C., & Jackson, S. (1997). Health effects of caregiving: The caregiver health effects study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 19, 110-116.

Seccombe, K., & Warner, R. L. (2004). Marriages and families: Relationships in social context. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Seltzer, M. M., Floyd, F., Song, J., Greenberg, J., & Hong, J. (2011). Midlife and aging parents of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Impacts of lifelong parenting. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 116, 479-499.

Slevin, K. F. (2010). “If I had lots of money…I’d have a body makeover”: Managing the aging body. Social Forces, 88(3), 1003-1020.

Stewart, S. D., Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2003). Union formation among men in the US: Does having prior children matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 90 – 104.

Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Way, N., Hughes, D., Yoshikawa, H., Kalman, R. K., & Niwa, E. Y. (2008). Parents’ goals for children: The dynamic coexistence of individualism and collectivism in cultures and individuals. Social Development, 17, 183–209.

Teachman, J. (2008). Complex life course patterns and the risk of divorce in second marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 294 – 305.

Teuscher, U., & Teuscher, C. (2006). Reconsidering the double standard of aging: Effects of gender and sexual orientation on facial attractiveness ratings. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(4), 631-639.

Torti, F. M., Gwyther, L. P., Reed, S. D., Friedman, J. Y., & Schulman, K. A. (2004). A multinational review of recent trends and reports in dementia caregiver burden. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 18(2), 99-109.

Vaillant, G. E. (2008). Spiritual evolution: A scientific defense of faith. New York: Doubleday Broadway.

Umberson, D., Williams, K., Powers, D., Chen, M., & Campbell, A. (2005). As good as it gets? A life course perspective on marital quality. Social Forces, 81, 493-511.

Wang, W., & Parker, K. (2014). Record share of Americans have never married: As values, economics and gender patterns change. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2014/09/2014-09-24_Never-Married-Americans.pdf

Wang, W., & Taylor, P. (2011). For Millennials, parenthood trumps marriage. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Witt, J. (2009). SOC. New York: McGraw Hill.

Wu, Z., Sun, L., Sun, Y., Zhang, X., Tao, F., & Cui, G. (2010). Correlation between loneliness and social relationship among empty nest elderly in Anhui rural area, China. Aging and Mental Health, 14, 108–112.

Yeager, C. A., Hyer, L. A., Hobbs, B., & Coyne, A. C., (2010). Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: The complex relationship between diagnosis and caregiver burden. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31(6), 376-384.

Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2015). Cohabitation in China: Trends and determinants. Population & Development Review, 41 (4), 607-628.

Zuidema, S. U., de Jonghe, J. F., Verhey, F. R., & Koopman, R. T. (2009). Predictors of neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home patients: Influence of gender and dementia severity. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(10), 1079-1086.