Section 2: Researching the Lifespan

2.1 Research in Lifespan Development

How do we study lifespan development?

A primary goal of this course is to help you learn more about how to constructively influence development. Whether we are aware of it or not, all of us are shaping development every day through our decisions and actions. Sometimes, this is obvious– when we are raising children or teaching preschoolers. In these situations, we know we are trying to help our children and students learn and grow. We think carefully about how we were raised or taught about our professional training. We take these responsibilities seriously. We know what a difference people in our lives have made to our development. However, in cases where we are not explicitly charged with promoting development, we may not think as carefully about our effects on others– like our friends, romantic partners, or parents. We may not think about our own development or the ways we nurture or disparage ourselves.

- Explain how the scientific method is used in researching development.

- Compare various types and objectives of developmental research.

- Compare and contrast three different research methodologies.

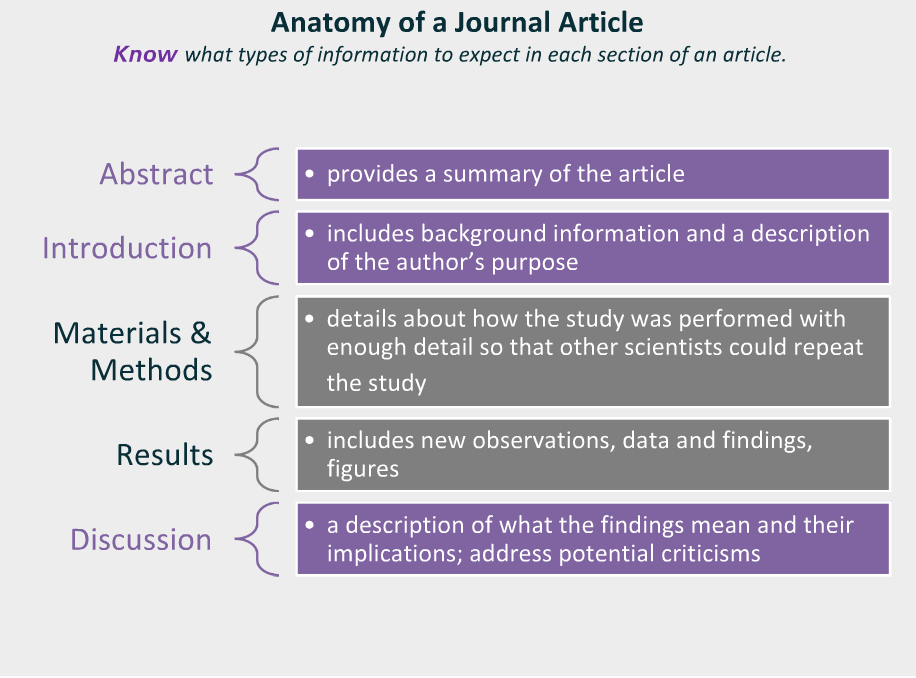

- Identify the parts of a journal article.

Introduction to Research

How do we know what changes and stays the same (and when and why) in families and individuals across the lifespan? We rely on research that utilizes the scientific method so that we can have confidence in the findings. How data are collected may vary by age group and by the type of information sought. The developmental design (for example, following individuals as they age over time or comparing individuals of different ages at one point in time) will affect the data and the conclusions that can be drawn from them about actual age changes. What do you think are the particular challenges or issues in conducting developmental research, such as with infants and children? Read on to learn more.

How do we know what we know?

At its core, science is a way of knowing: a set of practices for learning about the world. There are many other ways of knowing, including our intuition, emotions, and observations; the beliefs and customs of our families and neighbors; the opinions of friends and peers; communications from political and religious authorities; and messages from the media. If we bundle all these other sources of information together, they make up our“personal experience.” From this history, we form opinions about the contents of development: how people change and remain the same, what is “normal,” the causes of healthy and unhealthy development, and what we should do to be good parents, educators, and friends. Our experiences are embedded in particular cultural and historical contexts. These contexts have many strengths, but they also have their own implicit biases. Our personal convictions, based on a lifetime of experiences in these societal contexts and historical times, are naturally very compelling.

Personal Knowledge

A second source of information about how to support development can be called “professional experience.” Many callings and professions shape development, like parenting, education, nursing, social work, coaching, etc. And each comes with its own set of training, traditions, and practices. Some of these practices are drawn from research (as we will discuss shortly), others from personal experience of what has worked in the past, and others are simply “the way things have always been done.” Take, for example, the practices you see in our classroom: Learning takes place in groups, with a leader called the teacher, and involves readings, assignments, and grades. Such practices are based on a society’s history of carrying out these tasks, and educational and training programs reinforce them. Professional experiences are also embedded in the institutions of our time and place, as seen in schools, health care systems, human services, and other workplaces. These organizations and our education and training provide us with skills and information. At the same time, they have their own implicit biases. And, just like personal experience, professional experience has its own baked-in assumptions about humans and how they develop.

How do we know what we know? Take a moment to write down two things that you know about childhood. Okay. Now, how do you know? Chances are you know these things based on your own history (experiential reality), what others have told you, or cultural ideas (agreement reality) (Seccombe & Warner, 2004). There are several problems with personal inquiry, or drawing conclusions based on our personal experiences. Read the following sentence aloud:

Paris in the the spring

Are you sure that is what it said? Read it again:

Paris in the the spring

If you read it differently the second time (adding the second “the”) you just experienced one of the problems with relying on personal inquiry; that is, the tendency to see what we believe. Our assumptions very often guide our perceptions, consequently, when we believe something, we tend to see it even if it is not there. Have you heard the saying, “seeing is believing”? Well, the truth is just the opposite: believing is seeing. This problem may just be a result of cognitive ‘blinders’ or it may be part of a more conscious attempt to support our own views. Confirmation bias is the tendency to look for evidence that we are right and in so doing, we ignore contradictory evidence.

Science offers a more systematic way to make comparisons and guard against bias. One technique used to avoid sampling bias is to select participants for a study in a random way. This means using a technique to ensure that all members have an equal chance of being selected. Simple random sampling may involve using a set of random numbers as a guide in determining who is to be selected. For example, if we have a list of 400 people and wish to randomly select a smaller group or sample to be studied, we use a list of random numbers and select the case that corresponds with that number (Case 39, 3, 217, etc.). It is preferable to ask only those individuals with whom we are familiar to participate in a study; if we conveniently chose only people we know, we know nothing about those who had no opportunity to be selected. There are many more elaborate techniques that can be used to obtain samples that represent the composition of the population we are studying. However, even though a randomly selected representative sample is preferable, it is not always used because of costs and other limitations. As a consumer of research, however, you should know how the sample was obtained and keep this in mind when interpreting results. It is possible that what was found was limited to that sample or similar individuals and not generalizable to everyone else.

Scientific Methods

The particular method used to conduct research may vary by discipline, and since lifespan development is multidisciplinary, more than one method may be used to study human development. Because interventionists and practitioners use bodies of scientific evidence to transform systems and change practices in the world, it is crucial that researchers produce the highest quality evidence possible and evaluate and critique it thoughtfully. The tools that scientists use to generate such knowledge are called research methods or methodologies.

Many textbooks describe “the” scientific method as if there were only one way of knowing scientifically. Just as lifespan development spans multiple disciplines, each with its own preferred epistemologies and methodologies, we believe that there are multiple scientific methods or multiple perspectives, each one providing a complementary line of sight on a given target phenomenon. Social and developmental sciences have been critiqued for our reliance on a narrow range of methodologies, favoring methods that quantify observations (e.g., via surveys, ratings, or numerical codings) and control extraneous variables or confounds, either statistically or, for example, by bringing people into the lab. Social scientists often seem to favor these more quantitative methods and to discount methodologies that are more situated, contextualized, and wholistic, sometimes called qualitative methods. A third methodology, one that considers the strengths of the group being studied, falls under collaborative methods.

1. Deductive Methodologies: Quantitative

The scientific method typically involves quantitative research, which relies on numerical data or statistics to understand and report what has been studied. Quantitative researchers typically start with simple analyses like mean, median, mode, or frequency count and can utilize analyses to compare averages or find correlations between concepts.

The Scientific Method is a deductive method–in which a scientist starts with a falsifiable hypothesis and then conducts a series of observations to test whether the specifics on the ground are consistent with this hypothesis. It is one method of scientific investigation that involves the following steps, preferably guided by a theory:

- Determining a research question. Use initial observations to articulate a research question:

- Review previous studies (known as a literature review) to determine what has been found to date

- Identify the deficiencies or gaps in previous research

- Formulate a working theory of the target phenomenon and propose a hypothesis

- Conducting the study. Select or create a method of gathering information relevant to the hypothesis:

- Who? Sampling. Determine the people to be included

- What? Measurement. Determine the measures to be used to capture the phenomena of interest

- Where? Setting. Determine the setting where the study will take place

- How? and When? Design. Determine the study design.

- Interpreting the results. In light of everything you know, examine what the findings likely mean:

- Consider the limitations of the study

- Draw conclusions, including rejecting the hypothesis and revising the original theory

- Suggest future studies

- Publish:

- Making the findings available to others (both to share information and to have the work scrutinized by others)

The findings of these scientific studies can then be used by others to further explore the area of interest. Through this process, a literature or knowledge base is established. This model of scientific investigation presents research as a linear process guided by a specific research question.

2. Inductive Methodologies: Qualitative

A second set of procedures is more inductive. This process, often called grounded theory, starts with a general question and then constructs a theory of the phenomenon based not on the scientific community’s or researcher’s preconceived notions but on the researcher’s actual observations of many specific experiences on the ground. As you can see, in the process, the scientist foregrounds “looking” (the observations and experiences in the target setting) and uses this process to scaffold “thinking” (i.e., theorizing or building a mental model of what has been observed).

Qualitative research may involve steps such as these:

- Find a question: Begin with a broad area of interest and a research question

- Review the literature to justify the importance of the problem

- See how the problem fits into a larger set of issues

- Identify the deficiencies or gaps in other work on the topic

- Gather Information

- Who and where? Gain entrance into a group to be researched

- How? Gather field notes about the setting, the people, the structure, the activities or other areas of interest

- What? Ask open-ended, broad “grand tour” types of questions when interviewing subjects

- Reflect. Modify research questions as the study continues

- Make sense of the Information

- Note own participation and biases.

- Note patterns or consistencies

- Explore new areas deemed important by the people being observed

- Report findings

In this type of research, theoretical ideas are “grounded” in the participants’ experiences. The researcher is the student, and the people in the setting are the teachers who inform the researcher of their world (Glazer & Strauss, 1967). Researchers should be aware of their own biases and assumptions, acknowledge them, and report them in an effort to keep them from limiting accuracy in reporting results. Sometimes, qualitative studies are used initially to explore a topic, and then quantitative studies are employed to test or explain what was first described.

3. Collaborative Methodologies: CBPR

A third set of methodologies is based on the assumption that knowledge, research, and effective social action can best be co-constructed among researchers and community participants, incorporating the strengths and perspectives of all the stakeholders involved in a particular set of issues. This approach, often called community-based participatory action research, holds that complex social issues cannot be well understood or resolved by “expert” research, pointing to interventions from outside of the community that often have disappointing results or unintended side effects.

In collaborative approaches, researchers and community partners build a genuine trusting relationship, and this cooperative partnership is the basis on which all decisions about the project are made, from articulating a set of research questions to identifying data collection strategies, analysis and interpretation of information, and dissemination and application of findings.

The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) supports various CBPR projects addressing health disparities. These projects involve scientific researchers and community members collaborating on all aspects, from needs assessment to intervention design and implementation, aiming to address diseases and conditions disproportionately affecting populations experiencing health disparities. More information can be found on the NIMHD CBPR Program page (NIMHD).

Principles of Community Based Participatory Action Research (CBP

Community-Based Collaboration

- Researchers build a collaborative partnership with community members who are living with, involved in, or working on the problem of interest.

- This work is situated within neighborhoods and community organizations, building on their strengths and priorities.

- The goal is to facilitate change within the community itself, making it a more supportive context for all its inhabitants rather than removing individuals from the community for lab studies or individualized therapy.

Participatory Approach

- As the collaboration develops, members discuss and learn more about each other to co-create and frame a common agenda for research and action.

- These projects incorporate researchers’ expertise and goals while foregrounding the knowledge, concerns, and needs of community partners.

- For example, researchers interested in homeless youth could engage youth-serving organizations and the homeless youth themselves, consistent with the slogan popularized by the disability rights movement, “Nothing about us without us!”

- Community knowledge is irreplaceable as it provides key insights about target issues.

Action-Oriented Research

- All research activities are anchored by the larger goal of enhancing strategic action that leads to social change and community transformation.

- Community action can take various forms, such as public education campaigns, policy changes, or the creation of new public spaces like community gardens and farmers’ markets.

Informed Research Process

- The community action plan is informed by organizing existing information and collecting new data from key stakeholders relevant to the community issues.

- Research methods are planned collaboratively to produce high-quality information that is useful for making progress on the community agenda.

- All partners are involved in the scrutiny, visualization, discussion, and interpretation of data and jointly decide how it should be disseminated and used.

- These efforts feed into the next steps in both research and action.

Ongoing Collaboration

- University-community partnerships typically last for many years.

- Researchers are thoughtful about how to bring them to a successful close, ensuring that the collaboration builds capacity within the community so members can sustain collective action after the research team leaves.

Where is it Published?

Journal Articles

A good way to become more familiar with these scientific research methods, both quantitative and qualitative, is to look at journal articles, which are written in sections that follow these steps in the scientific process. Most psychological articles and many papers in the social sciences follow the writing guidelines and format dictated by the American Psychological Association (APA). In general, the structure is as follows: abstract (summary of the article), introduction or literature review, methods explaining how the study was conducted, results of the study, discussion and interpretation of findings, and references.

View the American Psychological Association’s document: Anatomy of a Journal Article.

Brené Brown is a bestselling author and social work professor at the University of Houston. She conducts grounded theory research by collecting qualitative data from large numbers of participants. In Brené Brown’s TED Talk, The Power of Vulnerability, Brown refers to herself as a storyteller-researcher as she explains her research process and summarizes her results.

Research Methods and Objectives

The main categories of psychological research are descriptive, correlational, and experimental research.

Research studies that do not test specific relationships between variables are called descriptive or qualitative studies. These studies are used to describe general or specific behaviors and attributes that are observed and measured. In the early stages of research, it might be difficult to form a hypothesis, especially when there is no existing literature on the subject. In these situations, designing an experiment would be premature, as the question of interest is not yet clearly defined as a hypothesis. Often, a researcher will begin with a non-experimental approach, such as a descriptive study, to gather more information about the topic before designing an experiment or correlational study to address a specific hypothesis.

Some examples of descriptive questions include:

-

- “How much time do parents spend with children?”

- “How many times per week do couples have intercourse?”

- “When is marital satisfaction greatest?”

Descriptive research is distinct from correlational research, in which psychologists formally test whether a relationship exists between two or more variables.

Experimental research goes a step further beyond descriptive and correlational research and randomly assigns people to different conditions, using hypothesis testing to make inferences about how these conditions affect behavior. Some experimental research includes explanatory studies, which are efforts to answer the question “why,” such as:

- “Why have rates of divorce leveled off?”

- “Why are teen pregnancy rates down?”

- “Why has the average life expectancy increased?”

Evaluation research is designed to assess the effectiveness of policies or programs. For instance, research might be designed to study the effectiveness of safety programs implemented in schools for installing car seats or fitting bicycle helmets. Do children who have been exposed to the safety programs wear their helmets? Do parents use car seats properly? If not, why not?

This Crash Course video provides a brief overview of psychological research, which we’ll cover in more detail on the coming pages.

You can view the transcript for “Psychological Research: Crash Course Psychology #2” here.

Additional Resources

Websites

- Psychological Research on the Net

- Want to participate in a study? Click on a link that sounds interesting to you in order to participate in online research.

- United States Census website

- U.S. Census Data is available and widely used to look at trends and changes taking place in the United States

- Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation

- KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization that fills the need for trusted, independent information on national health issues.

- Hidden Figures in Development Science

- The Society for Research in Child Development (SRCD) launched a project to increase the visibility of leading developmental scientists of color who have made critical research contributions and paved the way, through mentoring and advocacy, for younger scholars of color.

CBPR: a partnership approach to research that equitably involves, for example, community members, organizational representatives, and researchers in all aspects of the research process. All partners contribute expertise and share decision-making and ownership.

correlational research: research that formally tests whether a relationship exists between two or more variables; however, correlation does not imply causation

descriptive studies: research focused on describing an occurrence

evaluation research: research designed to assess the effectiveness of policies or programs

experimental research: research that involves randomly assigning people to different conditions and using hypothesis testing to make inferences about how these conditions affect behavior; the only method that measures cause and effect between variables

explanatory studies: research that tries to answer the question “why”

qualitative research: theoretical ideas are “grounded” in the experiences of the participants, who answer open-ended questions

quantitative research: involves numerical data that are quantified using statistics to understand and report what has been studied

Attributions

This chapter was adapted from:

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

References

Glazer, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine

Seccombe, K., & Warner, R. L. (2004). Marriages and families: Relationships in social context. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.