Section 2: Researching the Lifespan

2.2 Research Methods: Descriptive

Research Methods

“Methods” is also a name given to many different procedures scientists use to make their observations or collect information. Since developmentalists are interested in a wide range of human capacities, they want to know not only about people’s actions and thoughts, as expressed in words and deeds, but also about underlying processes, like abilities, emotions, desires, intentions, and motivations. Moreover, they want to go deeper, looking into biological and neurophysiological processes, and they want to consider many factors outside the person of study, looking at social relationships and interactions, as well as environmental materials, tasks, affordances, and societal contexts. As lifespan researchers, they want to study these capacities at all ages, from the tiniest babies to the oldest grandmothers. No wonder developmental scientists need so many tools and are inventing more all the time.

Every time you come across a conclusion in a textbook or research article (for example, when you read that “18-month-olds do not yet have a sense of self”), you should stop and ask, “How do you know that?” That is a great question. And a great scientific attitude. Over and over, we will want to scrutinize the evidence scientists are using to make their conclusions, considering carefully the extent to which the methods scientists use justify the conclusions they make. If a baby can’t yet talk, how would we know whether they have a sense of self? And even when a child can talk, what is the connection between what they tell us and what they are truly thinking? You can be sure that these kinds of questions stoke lively debates in scientific circles.

As with methodologies, more generally, science is strengthened by the use of a variety of approaches to collecting information. The strengths of others can compensate for one’s shortcomings. If we find that a new mother says that she is feeling stressed, and her best friend agrees, we see elevated cortisol levels. Her survey results are higher than usual, and she becomes irritated when her two-year-old makes a mess– well, we think we have captured something meaningful here. We are always in favor of multiple sources of data, and we especially appreciate methods that get us thick, rich information that is as close to lived experience in context as possible.

- Be familiar with the many methods lifespan development researchers use to gather information, including observations and self-reports, psychological tests and assessments, laboratory tasks, psychophysiological assessments, archival data or artifacts, case studies, and ethnographies.

- Identify the general strengths and limitations of different methods (e.g., reactivity, social desirability, accessibility, generalizability).

Methods of Gathering Information

Observation: Looking at people and their actions

Often considered the basic building blocks of developmental science, observational methods are those in which the researcher carefully watches participants, noting what they are doing, saying, and expressing, both verbally and nonverbally. Researchers can observe participants doing just about anything, including working on tasks, playing with toys, reading the newspaper, or interacting with others. Observations are ideal for gathering information about people’s verbal and physical behavior, but it is less clear whether internal states, like emotions and intentions, can be unambiguously discerned through observation.

Naturalistic observations take place when researchers conduct observations in the regular settings of everyday life. This method allows researchers to get very close to the phenomenon as it actually unfolds, but researchers worry that their participation may impact participants’ behaviors (a problem called reactivity). And, since researchers have little control over the environment, they realize that the different behaviors they observe may be due to differences in situational factors.

Laboratory observations, in contrast, take place in a specialized setting created by the researcher, that is, the lab. For example, researchers bring babies and their caregivers to the lab in a systematic procedure known as the strange situation, which you will learn about in the section on attachment. Observing in the lab allows researchers to set up a specific space and to have control over situational factors. However, researchers worry that the artificial nature of the situation may have an impact on people’s behavior and that the behaviors people show in the lab are not typical of the ones they show in regular contexts of daily life (a problem called generalizability).

Video or audio observations can be gathered using automatic recording devices that collect information even when a researcher is not present. For example, researchers ask caregivers to record family dinners or teachers to tape class sessions or place a small recording device on a young child’s chest that records every word the child says or hears. These records can then be watched or listened to by researchers. Such procedures reduce reactivity, but the resultant recordings are narrower in scope than what researchers could hear or see if they were present observing in the actual context.

Local expert observers can inform researchers about the verbal and non-verbal behavior of participants they have observed or interacted with many times. For example, caregivers and teachers can report on their children and students, and even children can provide their perspectives. Reports from others typically incorporate many more observations than a researcher could collect (e.g., a teacher sees a child in class every weekday), so the information is more representative of the target’s typical behavior. However, researchers worry that information could be distorted, for example, because reporters are biased or are not trained to observe or categorize the behaviors they have witnessed.

Participant observations, which are especially common in anthropology and sociology, take place when researchers gain entrance into a setting, not as an observer, but as a participant, with the aim of gaining a close and intimate familiarity with a given group of individuals or a particular community, and their behaviors, relationships, and practices. These observations are usually conducted over an extended period of time, sometimes months or years, which means that the observer can directly observe variations and changes in actions and interactions. Such observations provide rich and detailed information but are limited to the specific setting.

Self-reports: Listening to People and Their Thoughts

When researchers study people, one of the most common ways of gathering information about them is by asking them, via self-report methods. These can range from informal open-ended interviews or requests for participants to write responses to prompts all the way to surveys when participants can only choose among researcher-generated options. Self-report data are ideal for learning about people’s inner thoughts or opinions, but researchers worry that participants may distort the truth to present themselves in a favorable light (a problem called social desirability). There is also debate about whether participants can access some of their internal processes, like their genuine motivations.

Case studies involve exploring a single case or situation in great detail. Information may be gathered with the use of observation, interviews, testing, or other methods to uncover as much as possible about a person or situation. Case studies are helpful when investigating unusual situations such as brain trauma or children reared in isolation. They are often used by clinicians who conduct case studies as part of their normal practice when gathering information about a client or patient coming in for treatment. Case studies can be used to explore areas about which little is known and can provide rich detail about situations or conditions. However, the findings from case studies cannot be generalized or applied to larger populations because cases are not randomly selected, and no control group is used for comparison.

- Classic examples of case studies are the so-called baby diaries, in which researchers like Jean Piaget and William Stern conducted extensive observations on their individual children and took detailed notes about every aspect of their behavior and development. They also tested some of their hypotheses about development by giving their babies toys to play with or engaging them in interesting tasks. These case studies were conducted over the years. When case studies also extend into the past of the individual (for example, when researchers are interested in life review processes), they can be called biographical methods.

Ethnographies: Sometimes, researchers who focus on a group of individuals or a setting are particularly interested in the cultural context and its functioning. These studies can be called ethnographies. Drawn originally from anthropology, ethnographic methods describe an approach in which researchers carefully study and document people and their cultural settings, usually through extensive participant observation, interviews, and engagement in the setting. In these studies, as in all scientific investigations, researchers are the students, and the people in the setting are the teachers. Researchers strive to create a holistic, higher-order narrative account that privileges the perspectives of the people studied.

Surveys are familiar to most people because they are so widely used. Surveys enhance accessibility to subjects because they can be conducted in person, over the phone, through the mail, or online. A survey involves asking a standard set of questions to a group of subjects. In a highly structured survey, subjects are forced to choose from a response set such as “strongly disagree, disagree, undecided, agree, strongly agree” or “0, 1-5, 6-10, etc.” Surveys are commonly used by sociologists, marketing researchers, political scientists, therapists, and others to gather information on many variables in a relatively short period of time. Surveys typically yield surface information on a wide variety of factors but may not allow for an in-depth understanding of human behavior.

Of course, surveys can be designed in a number of ways. They may include forced-choice questions and semi-structured questions in which the researcher allows the respondent to describe or give details about certain events. One of the most difficult aspects of designing a good survey is wording questions in an unbiased way and asking the right questions so that respondents can give a clear response rather than choosing “undecided” each time. Knowing that 30% of respondents are undecided is of little use! So, a lot of time and effort should be put into the construction of survey items.

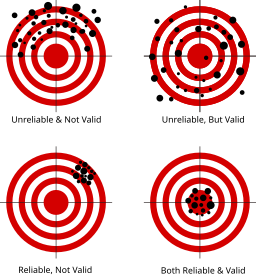

One of the benefits of having forced-choice items is that each response is coded so that the results can be quickly entered and analyzed using statistical software. The analysis takes much longer when respondents give lengthy responses that must be analyzed in a different way. Surveys are useful in examining stated values, attitudes, and opinions and reporting on practices. However, they are based on self-reports or what people say they do rather than on observation, which can limit accuracy. Validity refers to accuracy and reliability, which refers to consistency in responses to tests and other measures; great care is taken to ensure the validity and reliability of surveys (Figure 2).

Standardized, structured, or semi-structured interviews involve researchers directly asking a series of predetermined questions. Because researchers are present, they can ask follow-up questions, and participants can ask for clarification. This allows researchers to learn more from participants than they could from standardized questionnaires, but researchers worry that their presence could cause reactivity, such as when participants want to provide more socially desirable responses in a face-to-face setting than on an anonymous survey.

Open-ended interviews typically use targeted questions or prompts to get the conversation flowing and then follow the interview wherever it leads. This allows for more customized questioning and in-depth answers as researchers probe responses for greater clarity and understanding. However, since each respondent participates in a different interview conversation, it can be difficult to compare responses from person to person.

Focus groups involve group open-ended interviews, in which a small number of people (6-10) discuss a series of questions or prompts in guided or open discussion with a trained facilitator. In this format, focus group members listen and can react to each other’s comments and build discussion at the group level.

Responses to prompts are used when researchers ask participants to write down their thoughts. These can range from relatively unstructured free writes to short answers to a series of well-structured questions. Daily diaries, often organized electronically, allow participants to respond to online questions or prompts many days in a row.

In this video, Harvard psychologist Dan Gilbert explains survey research that was conducted to explore the way our preferences change over time.

Psychological Tests and Assessments: Mental Capacities and Conditions

Most of us are familiar with tests that measure IQ or other mental abilities and diagnostic assessments that classify people according to psychological conditions. When you read about the aging of intelligence, for example, some of those studies utilize measures of crystalized and fluid intelligence. Tests to measure mental abilities have been created for people of all ages, although it is not always clear how the measures used at different ages are connected to each other.

Laboratory Tasks: Interactions that Elicit or Capture Psychological Processes

Researchers create and invent all manner of tasks for participants to work on, either in the lab or in real-life settings (e.g., at home or school). These tasks allow researchers to set up activities that can assess a range of psychological attributes for people of all ages, ranging from problem-solving abilities to regulatory capacities (e.g., using the “Heads, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes” task), prosocial behaviors, learned helplessness, theories of mind, social information processing, rejection sensitivity, and so on. Many YouTube videos show children and adolescents participating in these tasks, and it is instructive to try to figure out exactly what is captured in each one. If you would like to see an example, you can watch a video of The Shopping Cart Study

Psychophysiological Assessment: Underlying Neurophysiological Functioning

Researchers also use a range of methods to capture information about neurophysiological functioning across the lifespan, including technology that can measure heart rate, blood pressure, hormone levels, and many kinds of brain activity to help explain development. These assessments provide information about what is happening “under the skin,” and researchers can see how these biological processes are connected to behavioral development. Usually, connections are bidirectional– neurophysiology contributes to the development of behavior, and behaviors shape physiological functioning and development.

Content Analysis

Content analysis involves looking at media such as old texts, pictures, commercials, lyrics or other materials to explore patterns or themes in culture. An example of content analysis is the classic history of childhood by Aries (1962) called “Centuries of Childhood” or the analysis of television commercials for sexual or violent content or for ageism. Passages in text or television programs can be randomly selected for analysis as well. Again, one advantage of analyzing work such as this is that the researcher does not have to go through the time and expense of finding respondents, but the researcher cannot know how accurately the media reflects the actions and sentiments of the population.

Secondary content analysis, or archival research, involves analyzing information that has already been collected or examining documents or media to uncover attitudes, practices, or preferences. There are a number of data sets available to those who wish to conduct this type of research. The researcher conducting secondary analysis does not have to recruit subjects but does need to know the quality of the information collected in the original study. Unfortunately, the researcher is limited to the questions asked and data collected originally.

U.S. Census Data is available and widely used to examine trends and changes in the United States (visit the United States Census website and check it out). A number of other agencies collect data on family life, sexuality, and many other areas of interest in human development (go to the NORC at the University of Chicago website or the Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation website and see what you find).

Try It

- case study: exploring a single case or situation in great detail. Information may be gathered with the use of observation, interviews, testing, or other methods to uncover as much as possible about a person or situation

- content analysis: involves looking at media such as old texts, pictures, commercials, lyrics or other materials to explore patterns or themes in culture

- Hawthorne effect: individuals tend to change their behavior when they know they are being watched

- observational studies, also called naturalistic observation, involve watching and recording the actions of participants

- reliability: when something yields consistent results

- secondary content analysis: archival research involves analyzing information that has already been collected or examining documents or media to uncover attitudes, practices, or preferences

- survey: asking a standard set of questions to a group of subjects

- validity: when something yields accurate results

Attributions

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

References

Ariès, P. (1962). Centuries of childhood. A social history of family life. New York: Vintage

Baer, D. M. (1973). The control of developmental process: Why wait? In J. R. Nesselroade & H. W. Reese (Eds.), Lifespan developmental psychology: Methodological issues (pp. 187-193). New York: Academic Press.

Baltes, P. B., Reese, H. W., & Nesselroade, J. R. (1977). Life-span developmental psychology: Introduction to research methods. Oxford, England: Brooks/Cole.

Cairns, R. B., Elder, G. H., & Costello, E. J. (Eds.). (2001). Developmental science. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Glazer, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine.

Lerner, R. M. (2006). Developmental science, developmental systems, and contemporary theories of human development. In R. M. Lerner (Vol. Ed.) and R. M. Lerner & W. E. Damon (Eds-in-Chief.). Handbook of child psychology: Vol 1, Theoretical models of human development(pp. 1-17). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Overton, W. F. (2010). Life‐span development: Concepts and issues. In W. F. Overton (Vol. Ed.) R.M. Lerner (Ed.-in-Chief), The handbook of life-span development: Vol. 1. Cognition, biology, and methods (pp. 1-29). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Overton, W. F., & Molenaar, P. (2015). Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (R. M. Lerner, Ed.-in-Chief): Vol 1, Theory and method. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Seccombe, K., & Warner, R. L. (2004). Marriages and families: Relationships in social context. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, & Mashburn, A. J. (2019). Lifespan developmental systems: Meta-theory, methodology, and the study of applied problems. An Advanced Textbook. New York, NY: Routledge.