Section 4: Birth and the Newborn

4.2 The Newborn

What is life like right after birth?

Learning Objectives

- Examine risks and complications with newborns

- Explain the postpartum recovery period

- Describe postpartum depression

The Newborn

The average newborn weighs approximately 7.5 pounds, although a healthy birth weight for a full-term baby is considered to be between 5 pounds, 8 ounces, and 8 pounds, 13 ounces. The average length of a newborn is 19.5 inches, increasing to 29.5 inches by 12 months and 34.4 inches by 2 years old (WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006).

For the first few days of life, infants typically lose about 5 percent of their body weight as they eliminate waste and get used to feeding. This often goes unnoticed by most parents, but it can cause concern for those who have a smaller infant. This weight loss is temporary, however, and is followed by a rapid period of growth.

Newborn Assessment and Risks

Assessing the Newborn

There are several ways to assess the condition of the newborn. The most widely used tool is the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS), developed by T. Berry Brazelton. This tool has been used around the world to help parents get to know their infants and to compare infants in different cultures (Brazelton & Nugent, 1995). The baby’s motor development, muscle tone, and stress response are assessed.

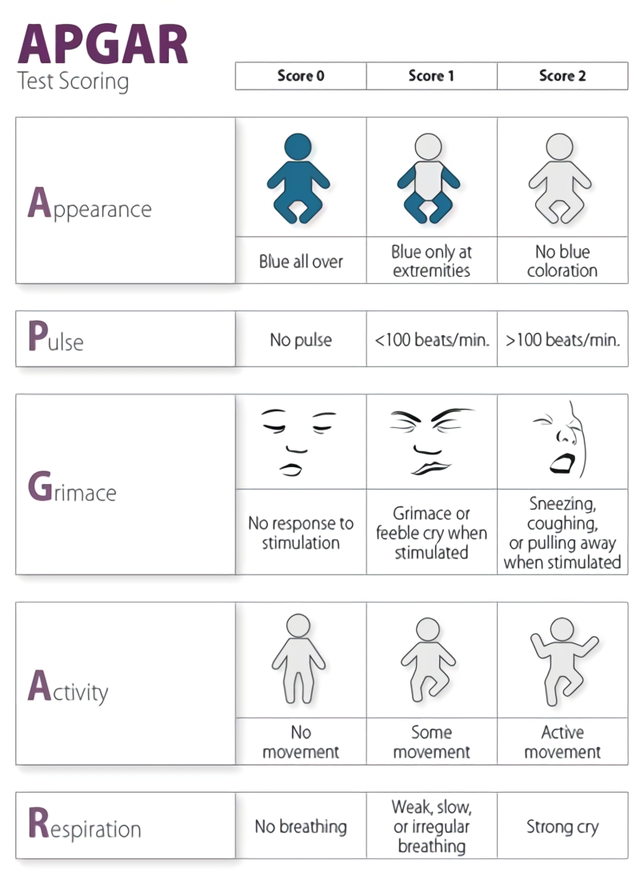

The Apgar assessment is conducted one minute and five minutes after birth by a medical professional (Figure 1). This is a very quick way to assess the newborn’s overall condition. Five measures are assessed: Heart rate, respiration, muscle tone (assessed by touching the baby’s palm), reflex response (the Babinski reflex is tested), and color. A score of 0 to 2 is given on each feature examined. An Apgar of 5 or less is cause for concern. The second Apgar should indicate improvement with a higher score.

Problems That May Exist with a Newborn

Anoxia and Hypoxia: One of the leading causes of infant brain damage is a lack of oxygen shortly after birth. Hypoxia occurs when the infant is deprived of an adequate amount of oxygen, leading to mild to moderate brain damage. Apoxia occurs when the infant undergoes a total lack of oxygen, which can lead to severe brain damage. Umbilical cord problems, birth canal problems, blocked airways, and placenta abruption typically cause this lack of oxygen. Both hypoxia and anoxia can lead to cerebral palsy and a host of other medical disorders.

Low birth weight: We have been discussing a number of teratogens associated with low birth weight, such as malnutrition, cocaine, tobacco, etc. A child is considered to have a low birth weight if they weigh less than 5.5 pounds (or under 2,500 grams). In 2016, about 8.17 percent of babies born in the United States were of low birth weight, and 1.4 percent were born with very low birth weight. Socioeconomic inequality is linked to low birth weight, and it’s more prevalent in the United States compared to the UK, Canada, and Australia (Martinson & Reichman, 2016).

A low birth weight baby has difficulty maintaining adequate body temperature because it lacks the fat that would otherwise provide insulation. Such a baby is also at more risk of infection. And 67 percent of these babies are also preterm, which can make them more at risk for a respiratory infection. Very low birth weight babies (under 1,500 grams or 3 pounds, 5 ounces) and extremely low birth weight (under 1,000 grams or 2 pounds, 3 ounces) have an increased risk of developing cerebral palsy. Many causes of low birth weight are preventable with proper prenatal care.

Preterm: A child might also have a low birth weight if it is born at less than 37 weeks gestation (which qualifies it as a preterm baby). In 2016, 9.85 percent of babies born in the U.S. were preterm. Early birth can be triggered by anything that disrupts the mother’s system. For instance, vaginal infections or gum disease can actually lead to premature birth because such infection causes the mother to release anti-inflammatory chemicals, which, in turn, can trigger contractions. Smoking and the use of other teratogens can also lead to preterm birth. A significant consequence of preterm birth includes respiratory distress syndrome, which is characterized by weak and irregular breathing (United States National Library of Medicine, 2015).

Small-for-date infants: Infants whose birth weights are below expectations based on their gestational age are referred to as small-for-date. These infants may be full-term or preterm but still weigh less than 90 % of all babies of the same gestational age.

Postpartum Period

The postpartum (or postnatal) period begins immediately after childbirth as the mother’s body, including hormone levels and uterus size, returns to a non-pregnant state. The terms puerperium, puerperal period, or immediate postpartum period are commonly used to refer to the first six weeks following childbirth. The World Health Organization (WHO) describes the postnatal period as the most critical and yet the most neglected phase in the lives of mothers and babies; most maternal and newborn deaths occur during this period.

A woman giving birth in a hospital may leave as soon as she is medically stable, which can be as early as a few hours postpartum, though the average for a vaginal birth is one to two days. The average cesarean section postnatal stay is three to four days. During this time, the mother is monitored for bleeding, bowel and bladder function, and baby care. The infant’s health is also monitored. Early postnatal hospital discharge is typically defined as the discharge of the mother and newborn from the hospital within 48 hours of birth.

The postpartum period can be divided into three distinct stages: the initial or acute phase, 6–12 hours after childbirth; the subacute postpartum period, which lasts two to six weeks; and the delayed postpartum period, which can last up to six months. In the subacute postpartum period, 87% to 94% of women report at least one health problem. Long-term health problems (persisting after the delayed postpartum period) are reported by 31% of women. Various organizations recommend routine postpartum evaluation at certain time intervals in the postpartum period.

Acute Phase

Postpartum uterine massage helps the uterus to contract after the placenta has been expelled in the acute phase. The first 6 to 12 hours after childbirth is the initial or acute phase of the postpartum period. During this time, the mother is typically monitored by nurses or midwives as complications can arise.

The greatest health risk in the acute phase is postpartum bleeding. Following delivery, the area where the placenta was attached to the uterine wall bleeds, and the uterus must contract to prevent blood loss. After contraction takes place, the fundus (top) of the uterus can be palpated as a firm mass at the level of the navel. It is important that the uterus remains firm, and the nurse or midwife will make frequent assessments of both the fundus and the amount of bleeding. Uterine massage is commonly used to help the uterus contract.

Following delivery, if the mother had an episiotomy or tearing at the opening of the vagina, it is stitched. In the past, an episiotomy was routine. However, more recent research shows that routine episiotomy, when a normal delivery without complications or instrumentation is anticipated, does not offer benefits in terms of reducing perineal or vaginal trauma. Selective use of episiotomy results in less perineal trauma. A healthcare professional can recommend comfort measures to help ease perineal pain.

Subacute Postpartum Period

Physical recovery

In the first few days following childbirth, the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is relatively high as hypercoagulability increases during pregnancy. It is maximal in the postpartum period, particularly for women with C-sections with reduced mobility. Anti-coagulants or physical methods such as compression may be used in the hospital, particularly if the woman has risk factors, such as obesity, prolonged immobility, recent C-section, or first-degree relative with a history of thrombotic episode. For women with a history of thrombotic events in pregnancy or prior to pregnancy, anticoagulation is generally recommended.

The increased vascularity (blood flow) and edema (swelling) of the woman’s vagina gradually resolve in about three weeks. The cervix gradually narrows and lengths over a few weeks. Postpartum infections can lead to sepsis and, if untreated, death. Postpartum urinary incontinence is experienced by about 33% of all women; women who deliver vaginally are about twice as likely to have urinary incontinence as women who give birth via a cesarean. Urinary incontinence in this period increases the risk of long-term incontinence. Kegel exercises are recommended to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles and control urinary incontinence. Discharge from the uterus, called lochia, will gradually decrease and turn from bright red to brownish to yellow and cease at around five or six weeks. An increase in lochia between 7–14 days postpartum may indicate delayed postpartum hemorrhage. In the subacute postpartum period, 87% to 94% of women report at least one health problem.

Infant care

At two to four days postpartum, a woman’s breast milk will generally come in. Historically, women who were not breastfeeding (nursing their babies) were given drugs to suppress lactation, but this is no longer medically indicated. In this period, difficulties with breastfeeding may arise. Maternal sleep is often disturbed as night waking is normal in the newborn, and newborns need to be fed every two to three hours, including during the night. The lactation consultant, health visitor, or postnatal doula (a person who helps the mother following the birth process) may be of assistance at this time.

Psychological disorders

During the subacute postpartum period, psychological disorders may emerge. Among these are postpartum depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and, in rare cases, postpartum psychosis. Postpartum mental illness can affect both mothers and fathers and is not uncommon. Early detection and adequate treatment are required. Approximately 70-80% of postpartum women will experience the “baby blues” for a few days. Between 10 and 20 percent may experience clinical depression, with a higher risk among those women with a history of postpartum depression, clinical depression, anxiety, or other mood disorders. The prevalence of PTSD following normal childbirth (excluding stillbirth or major complications) is estimated to be between 2.8% and 5.6% at six weeks postpartum.

Another subtype, peripartum onset (commonly referred to as postpartum depression), applies to women who experience major depression during pregnancy or in the four weeks following the birth of their child (APA, 2013). These women often feel very anxious and may even have panic attacks. They may feel guilty, agitated, and weepy. They may not want to hold or care for their newborn, even in cases in which the pregnancy was desired and intended. In extreme cases, the mother may have feelings of wanting to harm her child or herself. Most women with postpartum depression do not physically harm their children, but some do have difficulty being adequate caregivers (Fields, 2010). A surprisingly high number of women experience symptoms of peripartum-onset depression. A study of 10,000 women who had recently given birth found that 14% screened positive for postpartum depression and that nearly 20% reported having thoughts of wanting to harm themselves (Wisner et al., 2013).

Maternal-infant postpartum evaluation

Various organizations across the world recommend routine postpartum evaluation in the postpartum period. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recognizes the postpartum period (the “fourth trimester”) as critical for women and infants. Instead of the traditional single four- to six-week postpartum visit, ACOG, as of 2018, recommends that postpartum care be an ongoing process. They recommend that all women have contact (either in person or by phone) with their obstetric provider within the first three weeks postpartum to address acute issues, with subsequent care as needed. A more comprehensive postpartum visit should be done at four to twelve weeks postpartum to address the mother’s mood and emotional well-being, physical recovery after birth, infant feeding, pregnancy spacing and contraception, chronic disease management, and preventive health care and health maintenance.

Women with hypertensive disorders should have a blood pressure check within three to ten days postpartum. More than one-half of postpartum strokes occur within ten days of discharge after delivery. Women with chronic medical (e.g., hypertensive disorders, diabetes, kidney disease, thyroid disease) and psychiatric conditions should continue to follow up with their obstetric or primary care provider for ongoing disease management. Women with pregnancies complicated by hypertension, gestational diabetes, or preterm birth should undergo counseling and evaluation for cardiometabolic disease, as the lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease is higher in these women. Similarly, the World Health Organization recommends postpartum evaluation of the mother and infant at three days, one to two weeks, and six weeks postpartum.

Delayed Postpartum Period

The delayed postpartum period starts after the subacute postpartum period and lasts up to six months. During this time, muscles and connective tissue return to a pre-pregnancy state. Recovery from childbirth complications in this period, such as urinary and fecal incontinence, painful intercourse, and pelvic prolapse, are typically very slow and, in some cases, may not resolve. Symptoms of PTSD often subside in this period, dropping from 2.8% and 5.6% at six weeks postpartum to 1.5% at six months postpartum.

Approximately three months after giving birth (typically between two and five months), estrogen levels drop, and large amounts of hair loss are common, particularly in the temple area (postpartum alopecia). Hair typically grows back normally, but treatment is not indicated. Other conditions that may arise in this period include postpartum thyroiditis. During this period, infant sleep gradually increases during the night, and maternal sleep generally improves. Long-term health problems (persisting after the delayed postpartum period) are reported by 31% of women. Ongoing physical and mental health evaluation, risk factor identification, and preventive health care should be provided.

Cultural Viewpoints Post-Childbirth

Postpartum confinement refers to a system for recovery following childbirth. It begins immediately after the birth and lasts for a culturally variable length: typically for one month or 30 days, up to 40 days, two months, or 100 days. This postnatal recuperation can include “traditional health beliefs, taboos, rituals, and proscriptions.”The practice used to be known as “lying in,” which, as the term suggests, centers around bed rest. (Maternity hospitals used to use this phrase, as in the General Lying-in Hospital.) Postpartum confinement customs are well-documented in China, where it is known as “Sitting the Month,” and similar customs manifest all over the world. A modern version of this rest period has evolved to give maximum support to the new mother, especially if she is recovering from a difficult labor and delivery.

In other cultures, like South Korea, postnatal care is of great importance. Sanhujori is the term for traditional postnatal care in Korea and is a practice followed by the majority of women to ensure proper recovery after giving birth. Deeply rooted in Korean culture, sanhujori has similarly evolved with today’s society from being heavily reliant on the mother’s family members to including services that encompass its principles, which is apparent with the over 500 sanhujori centers (maternity hotels) in operation around Korea.

Newborn Nutrition

Proper nutrition in a supportive environment is vital for an infant’s healthy growth and development. From birth to 1 year, infants triple their weight and increase their height by half, and this growth requires proper nutrition. Breast milk is typically considered the ideal diet for newborns due to the nutritional makeup of colostrum and subsequent breast milk production. Breast milk is considered the ideal diet for newborns if/when the milk is free from drug and disease exposure (see below, When “breastfeeding” or “feeding breast milk” may not be an option). The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that infants be fed breast milk for the first 6 months of life and to introduce foods with breast milk until a child is 12 months old or older (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022a).

The World Health Organization (2018) recommends:

- initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth

- exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life

- introduction of solid foods at six months, together with continued breast milk up to two years of age or beyond

“Breastfeeding” or “being fed breast milk?” Many options and interpretations

Recommendations for “breastfeeding” can have different meanings. For instance, historically, breastfeeding has been defined as an infant snuggled on a mother’s breast and drinking milk directly from her breast. However, many options exist for feeding breast milk to an infant. A woman who has given birth can feed an infant directly from her breast, and milk can be expressed from a breast and fed through a bottle (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021a; Human Milk Banking: Association of North America, 2022; Mayo Clinic, 2021).

There are occasions when caregivers may be unable to breastfeed or provide breast milk for a variety of health, social, and emotional reasons. For example, breastfeeding may not be an option:

- when the nursing mother has a transmissible disease such as active, untreated tuberculosis or HIV,

- when the nursing mother is receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy,

- when the nursing mother is addicted to drugs or taking any medication that may be harmful to the baby (including some types of birth control),

- when there are attachment issues between the primary caregiver and the baby,

- when the mother or the baby is in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) after the delivery process or

- when the nursing mother does not produce enough breast milk (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022).

- However, as we learned above, breast milk can be purchased from a bank, which can remediate some of these complications.

Mothers can certainly continue to provide breast milk to their babies by expressing and freezing the milk to be bottle-fed at a later time or by being available to their infants at feeding time. However, some mothers find that after the initial encouragement they receive in the hospital to breastfeed, the outside world is less supportive of such efforts. Some workplaces support breastfeeding mothers by providing flexible schedules and welcoming infants, but many do not. In addition, not all women may be able to breastfeed. Women with HIV are routinely discouraged from breastfeeding as the infection may pass to the infant. Similarly, women who are taking certain medications or undergoing radiation treatment may be told not to breastfeed (United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Women’s Health, 2011).

Benefits of Breast Milk

Colostrum, the first breast milk produced during pregnancy and just after birth, has been described as “liquid gold” (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). Colostrum is packed with nutrients and other important substances that help the infant build up his or her immune system. Babies will typically get all the nutrition they need through colostrum during the first few days of life (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021b). Breast milk changes by the third to fifth day after birth, becoming much thinner but contains just the right amount of fat, sugar, water, and proteins to support overall physical and neurological development.

Breast milk also provides a source of iron more easily absorbed in the body than the iron found in dietary supplements. It typically provides resistance against many diseases, infants typically more easily digest it than formula, and it helps babies transition to solid foods more easily. Infants need high fat content due to the process of myelination, which requires fat to insulate the neurons. Breast milk has nutritional benefits and is free. Anyone who has priced formula recently can appreciate this added incentive to breastfeeding.

For most babies, breast milk is also easier to digest than formula. Formula-fed infants experience more diarrhea and upset stomachs. The absence of antibodies in the formula often results in a higher rate of ear infections and respiratory infections. Children who are breastfed have lower rates of childhood leukemia, asthma, obesity, type 1 and 2 diabetes, and a lower risk of SIDS. The USDHHS recommends that mothers breastfeed their infants until at least 6 months of age and that breast milk be used in the diet throughout the first year or two.

Benefits of feeding from the breast

Several recent studies have reported that it is not just babies that benefit from breastfeeding. Breastfeeding stimulates contractions in the uterus to help it regain its normal size, and women who breastfeed are more likely to space their pregnancies further apart.

Mothers who breastfeed are at lower risk of developing breast cancer (Islami et al., 2015), especially among higher-risk racial and ethnic groups (Islami et al., 2015; Redondo et al., 2012). Women who breastfeed have lower rates of ovarian cancer (Titus-Ernstoff et al., 2010) and reduced risk of developing Type 2 diabetes (Schwarz et al., 2010; Gunderson et al., 2015) and rheumatoid arthritis (Karlson et al., 2004). In most studies, these benefits have been seen in women who breastfeed longer than 6 months.

One early argument for promoting the practice of feeding from the breast (when health issues are not an issue) is that it promotes bonding and healthy emotional development for infants. However, research shows that breastfed and bottle-fed infants can adjust equally well emotionally (Fergusson & Woodward, 1999). Skin-to-skin contact is important for bonding and emotional development regardless of how infants receive their milk.

Video Example

Watch this video from the Psych SciShow, “Bad Science: Breastmilk and Formula,” to learn about research related to breastfeeding and formula feeding.

To learn more about breastfeeding, visit this resource from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources: Your Guide to Breastfeeding.

Visit Kids Health on Breastfeeding vs. Formula Feeding to learn more about the benefits and challenges of each. You can listen to the article’s narration by clicking on the speaker icon.

A meta-analysis (Anderson et al., 1999) has revealed that breastfeeding is connected to advantages with cognitive development. Low birth weight infants had greater benefits from breastfeeding than did normal-weight infants in a meta-analysis of twenty controlled studies examining the overall impact of breastfeeding. This meta-analysis showed that breastfeeding may provide nutrients required for rapid development of the immature brain and be connected to more rapid or better development of neurologic function. The studies also showed that a longer duration of breastfeeding was accompanied by greater differences in cognitive development between breastfed and formula-fed children. Whereas normal-weight infants showed a 2.66-point difference, low-birth-weight infants showed a 5.18-point difference in IQ compared with weight-matched, formula-fed infants. These studies suggest that nutrients present in breast milk may have a significant effect on neurologic development in both premature and full-term infants. Starting good nutrition practices early on can help children develop healthy dietary patterns, and infants need proper nutrients to fuel their rapid physical growth. Without proper nutrition, infants are at risk for malnutrition, which can result in physical, cognitive, emotional, and social consequences.

The use of wet nurses, or lactating women, hired to nurse others’ infants during the Middle Ages eventually declined, and mothers increasingly breastfed their own infants in the late 1800s. In the early part of the 20th century, breastfeeding began to decline again. By the 1950s, it was practiced less frequently by middle-class, more affluent mothers as formula began to be viewed as superior to breast milk.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, there was again a greater emphasis placed on natural childbirth and breastfeeding, and the benefits of breastfeeding were more widely publicized. Gradually, rates of breastfeeding began to climb, particularly among middle-class, educated mothers who received the strongest messages to breastfeed.

In the 1960s, formula companies led campaigns in developing countries to encourage mothers to feed their babies infant formula. Many mothers felt that formula would be superior to breast milk and began using formula. The use of formula can be healthy under conditions in which there is adequate, clean water with which to mix the formula and adequately sanitize bottles and nipples. However, in many countries, such conditions were not available, and babies often were given diluted, contaminated formula that made them sick with diarrhea and led to dehydration. These conditions continue today in some developing countries, and hospitals in those developing countries prohibit the distribution of formula samples to new mothers in an effort to get them to rely on breastfeeding. Many mothers in these countries do not understand the benefits of breastfeeding and have to be encouraged and supported to promote this practice.

When Breastfeeding or Breast Milk is Not Available

There are occasions when caregivers may be unable to breastfeed or provide breast milk for a variety of health, social, and emotional reasons. For example, breastfeeding may not be an option:

- when the nursing mother has a transmissible disease such as active, untreated tuberculosis or HIV,

- when the nursing mother is receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy,

- when the nursing mother is addicted to drugs or taking any medication that may be harmful to the baby (including some types of birth control),

- when there are attachment issues between the primary caregiver and the baby,

- when the mother or the baby is in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) after the delivery process or

- when the nursing mother does not produce enough breast milk (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022).

However, as we learned above, breast milk can be purchased from a bank, which can remediate some of these complications.

Cultural Differences in Breastfeeding

Intriguingly, breastfeeding rates are higher among immigrants than among non-immigrants (Dennis et al., 2019). In the United States, mothers born in the U.S. were actually less likely to breastfeed than foreign-born mothers (Gibson-Davis & Brooks-Gunn, 2006). This difference may contribute to what researchers have called the immigrant paradox (Coll & Marks, 2012).

Because immigrants are more likely to have a lower SES, one might expect their children to be less likely to be breastfed and more likely to experience negative outcomes. However, research has often found the opposite pattern. In addition to higher rates of breastfeeding, children of immigrants tend to be healthier and experience greater long-term educational achievements than children born to women of the same ethnic and socioeconomic group. This counter-intuitive finding highlights some of the strengths that immigrants bring to their new communities and suggests fruitful avenues for more research.

Global Considerations and Malnutrition

In the 1960s, formula companies led campaigns in developing countries to encourage mothers to feed their babies on infant formula. Many mothers felt that formula would be superior to breast milk and began using formula. The use of formula can certainly be healthy under conditions in which there is adequate, clean water with which to mix the formula and adequate means to sanitize bottles and nipples. However, in many of these countries, such conditions were not available, and babies often were given diluted, contaminated formula, which made them sick with diarrhea and dehydrated. These conditions continue today, and now many hospitals prohibit the distribution of formula samples to new mothers in an effort to get them to rely on breastfeeding. Many of these mothers do not understand the benefits of breastfeeding and have to be encouraged and supported in order to promote this practice.

According to WHO, malnutrition is defined as the low or excessive intake of nutrients, which can cause undernutrition or overweight/obesity. Malnutrition is classified into four categories: wasting, stunting, underweight, and micronutrient deficiencies (Figure 5) (World Health Organization, 2021).

Wasting occurs when a person has limited food intake with limited nutrients. A child who experiences wasting has a higher risk of dying if left untreated. It is often measured when the child has a lower weight for their height. Stunting, on the other hand, is measured when there is low height for age. It is caused by the lack of enough and properly balanced diet for a long period due to poverty, maternal health and nutrition, frequent illnesses, inappropriate feeding, and care from a younger age. An underweight child is a child that has a low weight for their age. They often can be stunted, wasted, or both (World Health Organization, 2021).

Malnutrition is a significant public health problem in several developing countries. In Niger, a country in West Africa with the youngest population, malnutrition persists across the country. It is reported that about 15.0% of children were classified as acutely malnourished in 2018. About 47.8% of children are stunted due to malnutrition. Stunting negatively affects cognitive and physical development, which also harms the country’s economy. It is projected that stunting will increase by 44 % by 2025 as the population in Niger continues to grow (UNICEF NIGER, 2021).

Children in developing countries and countries experiencing the harsh conditions of war are at risk for two major types of malnutrition. Infantile marasmus refers to starvation due to a lack of calories and protein. Children who do not receive adequate nutrition lose fat and muscle until their bodies can no longer function. Babies who are breastfed are much less at risk of malnutrition than those who are bottle-fed. After weaning, children who have diets deficient in protein may experience kwashiorkor, or the “disease of the displaced child,” often occurring after another child has been born and taken over breastfeeding. This results in a loss of appetite and swelling of the abdomen as the body begins to break down the vital organs as a source of protein.

Breastfeeding could save the lives of millions of infants each year, according to the WHO, yet fewer than 40 percent of infants across the world are breastfed exclusively for the first 6 months of life. Because of the great benefits of breastfeeding, WHO, United Nations Children’s Fund, formerly United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), and other national organizations are working together to step up support for breastfeeding across the world.

Find out more statistics and recommendations for breastfeeding at the WHO’s 10 Facts on Breastfeeding.

You can also learn about efforts to promote breastfeeding in Peru at “Protecting Breastfeeding in Peru.”

Milk Anemia in the United States

Many infants suffer from milk anemia, a condition in which milk consumption leads to a lack of iron in the diet. The body gets iron through certain foods. The prevalence of iron deficiency anemia in 1- to 3-year-old children seems to be increasing (Kazal, 2002). Toddlers who drink too much cow’s milk may also become anemic if they are not eating other healthy foods that have iron. This can be due to the practice of giving toddlers milk as a pacifier when resting, riding, walking, and so on. Appetite declines somewhat during toddlerhood, and a small amount of milk (especially added chocolate syrup) can easily satisfy a child’s appetite for many hours. The calcium in milk interferes with the absorption of iron in the diet as well. There is also a link between iron deficiency anemia and diminished mental, motor, and behavioral development. In the second year of life, iron deficiency can be prevented by the use of a diversified diet that is rich in sources of iron and vitamin C, limiting cow’s milk consumption to less than 24 ounces per day, and providing a daily iron-fortified vitamin (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998).

Introducing Solid Foods

When to Introduce More Solid Foods: Solid foods should not be introduced until the infant is ready. According to The Clemson University Cooperative Extension (2014), some things to look for include the infant:

- can sit up without needing support,

- can hold its head up without wobbling,

- shows interest in foods others are eating,

- is still hungry after being breastfed or formula-fed,

- is able to move foods from the front to the back of the mouth and

- is able to turn away when they have had enough.

Solid foods can be introduced from around six months onward when babies develop stable sitting and oral feeding skills but should be used only as a supplement to breast milk or formula. By six months, the gastrointestinal tract has matured, solids can be digested more easily, and allergic responses are less likely. The infant is also likely to develop teeth around this time, which aids in chewing solid food. Iron-fortified infant cereal, made of rice, barley, or oatmeal, is typically the first solid introduced due to its high iron content. Cereals can be made of rice, barley, or oatmeal (Figure 6). Generally, salt, sugar, processed meat, juices, and canned foods should be avoided.

Though infants usually start eating solid foods between 4 and 6 months of age, growing toddlers consume more and more solid foods. Pediatricians recommend introducing foods one at a time and for a few days to identify potential food allergies. Toddlers may be picky at times, but it remains important to introduce a variety of foods and offer food with essential vitamins and nutrients, including iron, calcium, and vitamin D.

Finger foods such as toast squares, cooked vegetable strips, or peeled soft fruit can be introduced by 10-12 months. New foods should be introduced one at a time, and the new food should be fed for a few days in a row to allow the baby time to adjust to the new food. This also allows parents time to assess if the child has a food allergy. Foods that have multiple ingredients should be avoided until parents have assessed how the child responds to each ingredient separately. Foods that are sticky (such as peanut butter or taffy), cut into large chunks (such as cheese and harder meats), and firm and round (such as hard candies, grapes, or cherry tomatoes) should be avoided as they are a choking hazard. Honey and Corn syrup should be avoided as these often contain botulism spores. In children under 12 months, this can lead to death (Clemson University Cooperative Extension, 2014).

Additional Supplemental Resources

Websites

- The AAP Parenting Website

- The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) promotes pediatrics and advances child health priorities in various ways. This website is dedicated to our mission—to better the health of children worldwide by empowering parents and caregivers with the needed resources and information.

Videos

- APGAR Score

- The Apgar score is a scoring system used to assess the health of newborns and identify those who require emergent attention. It ranges from zero to 10 and is calculated by evaluating the newborn based on five criteria. This video reviews how to calculate an APGAR score.

- Reflexes in Newborn Babies

- All full-term babies should be born with some natural reflexes like the sucking and walking reflex. Registered Nurse Sarah demonstrates some of these reflexes, which is a useful review for pediatric nursing students.

- Reducing fear of birth in U.S. culture

- This Tedx talk features Ina May Gaskin, MA, CPM, PhD (Hon), founder and director of the Farm Midwifery Center in Tennessee. The 41-year-old midwifery service is noted for its women-centered care.

Attributions

Human Growth and Development by Ryan Newton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License,

Individual and Family Development, Health, and Well-being by Diana Lang, Nick Cone; Laura Overstreet, Stephanie Loalada; Suzanne Valentine-French, Martha Lally; Julie Lazzara, and Jamie Skow is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

Human Development by Human Development Teaching & Learning Group under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License,

References

Anderson, J. W., Johnstone, B. M., & Remley, D. T. (1999). Breast-feeding and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70(4), 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/70.4.525

Brazelton, T. B., & Nugent, J. K. (1995). Neonatal behavioral assessment scale. London: Mac Keith Press.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1998). Recommendations to prevent and control iron deficiency in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00051880.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015c). Preterm birth. http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pretermbirth.htmCenters for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021a). Nutrition. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/InfantandToddlerNutrition/breastfeeding/pumping-breast-milk.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b). What to expect while breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/InfantandToddlerNutrition/breastfeeding/what-to-expect.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021c). Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/features/breastfeeding-benefits/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Breastfeeding: Breastfeeding and special circumstances. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/Contraindications-to-breastfeeding.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022a). Breastfeeding: Frequently asked questions (FAQS). https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/faq/#howlong

Children’s Welfare. (1998). Welfarem-L Digest, June 25. Retrieved August 10, 2006, from welfare-L@American.edu

Clemson University Cooperative Extension. (2014). Introducing Solid Foods to Infants. http://www.clemson.edu/extension/hgic/food/nutrition/nutrition/life_stages/hgic4102.html

Coll, C. G., & Marks, A. K. (Eds.). (2012). The immigrant paradox in children and adolescents: Is becoming American a developmental risk? American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13094-000

Dennis, C.-L., Shiri, R., Brown, H. K., Santos, H. P., Jr., Schmied, V., & Falah-Hassani, K. (2019). Breastfeeding rates in immigrant and non-immigrant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 15(3), e12809. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12809

Fergusson, & Woodward. (1999). Breastfeeding and later psychosocial adjustment. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 13(2), 144–157. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3016.1999.00167.

Gibson-Davis, C. M., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2006). Couples’ immigration status and ethnicity as determinants of breastfeeding. American Journal of Public Health, 96(4), 641–646. https://www.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.064840

Gunderson, E. P., Hurston, S. R., Ning, X., Lo, J. C., Crites, Y., Walton, D., Dewey, K. G., Azevedo, R. A., Young, S., Fox, G., Elmasian, C. C., Salvador, N., Lum, M., Sternfeld, B., Quesenberry, C. P., Jr, & Study of Women, Infant Feeding and Type 2 Diabetes After GDM Pregnancy Investigators. (2015). Lactation and progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort Study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(12), 889–898. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-0807

Human Milk Banking: Association of North America. (2022). Milk banking frequent questions. https://www.hmbana.org/about-us/frequent-questions.html

Islami, F., Liu, Y., Jemal, A., Zhou, J., Weiderpass, E., Colditz, G…Weiss, M. (2015). Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk by receptor status – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology, 26, 2398-2407.

Karlson, E.W., Mandl, L.A., Hankison, S. E., & Grodstein, F. (2004). Do breast-feeding and other reproductive factors influence the future risk of rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis & Rheumatism, 50 (11), 3458-3467.

Kazal, J. L. (2002). Prevention of iron deficiency in infants and toddlers. American Family Physician, 66(7), 1217-1224.

Mayo Clinic. (2014). Labor and delivery, postpartum care. http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/labor-and-delivery/in-depth/inducing-labor/art-20047557

Mayo Clinic. (2021). Infant and toddler health. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/infant-and-toddler-health/expert-answers/induced-lactation/faq-20058403

Redondo, C. M., Gago-Domínguez, M., Ponte, S. M., Castelo, M. E., Jiang, X., García, A. A., Fernández, M. P., Tomé, M. A., Fraga, M., Gude, F., Martínez, M. E., Garzón, V. M., Carracedo, Á., & Castelao, J. E. (2012). Breastfeeding, parity, and breast cancer subtype in a Spanish cohort. PloS One, 7(7), e40543. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040543

Schwarz, E. B., Brown, J. S., Creasman, J. M., Stuebe, A., McClure, C. K., Van Den Eeden, S. K., & Thom, D. (2010). Lactation and maternal risk of type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. The American Journal of Medicine, 123(9), 863.e1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.03.016

Titus-Ernstoff, L., Rees, J. R., Terry, K. L., & Cramer, D. W. (2010). Breast-feeding the last born child and risk of ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes & Control: CCC, 21(2), 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-009-9450-8

UNICEF NIGER (2021). Nutrition. https://www.unicef.org/niger/nutrition

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2012). A profile of older Americans: 2012. http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/Profile/2012/docs/2012profile.pdf

United States National Library of Medicine. (2015). Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001563.htm

United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Women’s Health (2011). Your guide to breastfeeding. Washington D.C.

Weitz, R. (2007). The sociology of health, illness, and health care: A critical approach, (4th ed.). Thomson.

Wisner K. L., Sit, D. K. Y., McShea, M. C., Rizzo, D. M., Zoretich, R. A., Hughes, C. L., Hanusa, B. H. (2013). Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry, 70, 490–498.

World Health Organization. (2018) Breastfeeding. https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/breastfeeding

World Health Organization. (2021). Malnutrition. https://www.who.int/health-topics/malnutrition#tab=tab_2