6

Visitors

Over the years the list of visitors in each semester not only added up to a who’s who of the Australian defence hierarchy but also was interleaved with dignitaries of overseas military forces and governments, scions of politics, academe and the third and fourth estates, and latterly returning graduates and staff. From the beginning the members of the Military Board including its chairmen, the successive ministers for army, made the pilgrimage to Portsea, and the Board made a point of allotting in turn the general officers of the army to take the graduation parade, with vice regal and inter-service patronage in other years to enhance the image of the academy. In the later years there was an unfortunate repetitive over-attendance by chiefs of the general staff, but at least there was never a shortage of a well-qualified inspecting officer.

Visitors to OCS

Sir Roden Cutler inspecting a guard of honour

Campus November 1983

Visiting the School to deliver the Harrison memorial lecture, Sir Roden Cutler is accompanied by BSM UO B.J. McLauchlin and commandant Col G.D. Burgess, passing M. Baumback, R.D. Bryett, P.S. Westbury, R.J. Youren in the front rank and M.H. Leary, S.M. Saddington, M.J. Butler, J.R. Bassett in the rear rank.

RMC Archives

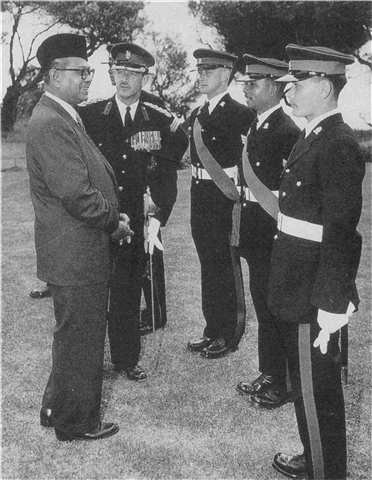

Prime Minister of Malaya

visiting Portsea, 1959

With Federation of Malaya students becoming regular attenders at OCS, visiting Prime Minister Tumku Abdul Rahman naturally took the opportunity to speak to all the overseas students and their mentors.

Accompanied by commandant Col J.G Ochiltree OBE, he is with Sgt D.J. McLachlan, Cpl Samsoodeen Izaidin bin Mohd Rahim and OIC Tan Soon Aun.

He was one of a stream of political leaders and senior servicemen who visited to make contact with their cadets, both to satisfy curiosity and to give them a feeling of not being forgotten while they were in a strange land.

Photo: D.J. McLachlan

Arrival AVM Nguyen Cao Ky

Portsea January 1967

With Australia strongly committed to assisting the government of the Republic of Vietnam to withstand the internal revolutionary forces and the invading ones from North Vietnam, and an increasing dissatisfaction of this support from the sincere and the fellow travellers within Australia, this state visit was aimed at bolstering the Australian government position and confirming its firm support for the beleaguered country.

Ky is accompanied by his wife and Prime Minister Harold Holt and wife, conducted on arrival by commandant Col H.G. Bates. The cadets, as was usual, provided a guard of honour for the visitors.

OCS Scrapbook 1967

There was, however, a noticeable fall off in military board visits after the 1969 move of the general staff, adjutant general and quartermaster general branches of Army Headquarters to Canberra, leaving the Master General of the Ordnance as their outpost in Melbourne. Not that there was any fall off in military visitors, the gap being amply filled by the ambassadors and high commissioners, military attaches and visiting senior officers of the overseas countries whose students were then beginning to form a regular component of the student body, and similar representatives from other friendly countries: Brunei, Burma, Cambodia, Ceylon, Federation of Malaya and Malaysia, Fiji, France, India, Indonesia, Laos, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Pakistan, Philippines, Republic of Vietnam, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand, United Kingdom and United States of America. The commandants and staff of other colleges also passed through: starting with the RAF College Cranwell in 1953 there followed visitors from the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, Mons Officer Cadet School, Staff College Camberley, Federation Military College-Royal Military College and the Military Training School of Malaysia, Military Technical Training School Bangkok, PNG Military Cadet School, Republic of Vietnam National Military Academy, US Military Academy West Point as well as the Australian ones, Staff College Queenscliff’ RAN College Flinders and Jervis Bay, RAAF Academy Point Cook, RMC Duntroon, OTU Scheyville and the Officer Training Wing of the WRAAC School Georges Heights (1).

Senior Malaysian Officer Visit – May 1967

The Malaysian Chief of the Armed Forces, General Tunku Osman, today visited the Officer Cadet School, Portsea during a series of visits to defence establishments. General Osman was greeted on his arrival at the Officer Cadet School with a Guard of Honour mounted by approxiately 100 officer cadets currently on the course. He inspected the guard of honour and was accorded a General Salute. From the parade ground, the General proceeded to an informal address of the officer cadets assembled in one of the lecture halls. He told them he was pleased the Australian Government extends its facilities to train Malaysian officer cadets at the Officer Cadet School. He said his brother in law had trained at OCS during the early 1950’s and his aide-camp, Capt Hasbullah, who is accompanying him on the visit to Australia, was also a graduate of the School. General Osman presented the plaque of the Malaysian Armed Forces “in appreciation for what the College has done for Malaysian officers”. Concluding his address, the General moved to the library, where he had an informal discussion with the four Malaysian officer cadets curently at Portsea. General Tunku Osman commenced his Australian tour on May 4, and returns home next Thursday, May 18. Tomorrow, Saturday May 13, he leaves by air to continue his visit in Queensland.

Source: AWM Video

After its building and refurbishment programme in the mid-1960s Portsea had become something of a showpiece, and therefore was automatically placed on the itinerary of any visiting dignitaries or of other visitors with a difficult to fill programme, providing a view of the Australian Army sure to impress from both the environment and military standards viewpoint. Politicians and public servants connected with defence were also directed there in one of the less astute moves prevalent in the army, of showing them over the best instead of worst establishments, so convincing them that army accommodation and facilities were of a high standard and further funds for construction were not a high priority. Ministers of State, delegations to SEATO conferences and the annual Chief of the General Staff Exercises supplemented the steady stream of other international visitors to the School. The Sultan of Pahang and his wife visited in 1960 to see their son who was a student, and resident and transient representatives of various countries also came to maintain contact with their cadets. Prime Minister of Vietnam AVM Nguyen Cao Ky visited in January 1967 accompanied by local resident Prime Minister Harold Holt, whose unofficial visit to Cheviot Beach later in the year ended in his disappearance and a search in which the School was closely involved.

Search for Harold Holt – Cheviot Beach 18 December 1967

A frequenter of the Portsea ocean beaches, Prime Minister Harold Holt disappeared while swimming at Cheviot Beach Sunday 17 December when the School was in recess. The duty officer of OCS was informed and the School staff assisted in the fruitless search.

Many theories have been advanced on how and why he disappeared, ranging from the outlandish to the simply political. The reality remains a public mystery, that is if the idea of a simple drowning of a strong and experienced swimmer in a strong sea is discounted. A year later an underwater plaque was mounted on a reef in the area where Holt was last seen.

Nepean Historical Society

Others came for more functional purposes: corps directors to solicit and interview prospective appointees to their corps; staff officers from Army Headquarters-Army Office, Headquarters Southern Command and later 3rd Military District to assist with administrative and training problems; Department of Works representatives on building and erosion control programmes; chaplains and chaplains general for religious services and character guidance courses; and the Fox Committee looking at officer training in the wake of an RMC bastardisation scandal was able to lean on OCS’s already advanced liberalisation programme as guidelines for a constructive approach where the course ‘trains cadets to be officers, where they must be able to organise their lives to fit a military system without supervision’. There were also attempts to use visits to promote OCS as a desirable career, starting with the headmaster of Scotch College Perth in mid-1953, two groups in 1960 mostly from the Melbourne area, representatives from National Service battalions from 1954 and cadre staffs of school cadet units in 1959-60. Subsequently, with a different approach, courses for army recruiters visited the School from 1965 onwards to get an understanding of the message they had to carry.

It was always the aim of successive commandants to bring in prestigious and well qualified lecturers on specific subjects to enhance both content and quality of the courses. The nature of these lecturers changed as emphasis on different aspects changed. In the absence of formal tuition on international affairs, early speakers were brought from Melbourne University, arms of the service were covered by corps directors, and the Bishop of Geelong dealt with religious and moral matters until introduction of character guidance courses in 1955. Those lectures changed their character as current affairs, military geography and government were phased into the course, with more senior military officers covering international affairs and expert lecturers presenting a variety of civil aspects – police, railways, industry, the antarctic, and such social aspects as the law, television, banking, insurance and architecture. Then during the 1960s, as the School strengthened its own academic programme and faculty, and began regular visits to army schools and cultural centres, the need of these visitors seemed to fade, the subjects being generally covered internally and during the external tours, other than for keynote addresses by such experts as Dr T.B. Millar from Australian National University and Mr M. Brown, principal of the Administrative Staff College. However there was a reversion to a solid external input during the 1970s with well known academic figures from a variety of universities lecturing on politics, strategic studies, international affairs, economics, political science and management, with a later reintroduction of such topical social issues as road safety and drug abuse.

Visits from sister colleges began early with regular sporting interchanges with the RAN College then located at Flinders and RAAF Academy Point Cook, followed in 1953 by the arrival of a rugby team from RAF Cranwell. Then the following year by Second Class of RMC Duntroon, on an industrial tour during a so-called term break, called in for a programme comprising a game of rugby, entertainment and a savage rocket by OCS instructor Capt T.M. Tripp for not having greatcoats buttoned to the neck as it was ‘in my day’. These openers heralded regular exchanges whenever the financial situation could bear it, usually coordinated with other activities, and were augmented by such occasions as a party from the US Military Academy West Point in 1978.

USMA cadets singing for their supper – Rec Room 3 August 1978

As part of a familiarisation tour, a party of West Point cadets visited Australian establishments, with OCS in the itinerary. A performance in the recreation room was part of the price of their own entertainment.

The memorabilia on the wall were part of the inheritance taken on from OTU Scheyville after it closed in 1973. This, with OCS’s own boards, flags and trophies were transferred to Duntroon in 1985, both sets featuring in the cadets’ mess and trophy room.

OCS Scrapbook 1978

Trips Away

Armoured training – Puckapunyal 1959

Although labelled a demonstration, the visit enabled some hands-on activity which included travelling in armoured personnel carriers, tanks and support vehicles, directing tank fire and observing or participating in infantry-tank cooperation training.

The same applied to similar activities: artillery demonstrations might include digging in the trail of a 25 pr gun to fire in the upper register; engineering the erection of a bridge; and firing infantry heavy weapons unavailable at Portsea. To the interested they gave a background which came in good stead in later service; for the uninterested, stories of who was asleep abounded. The course at OCS developed a smorgasbord from which different students took different inputs.

Photo: D.J. McLachlan

While it was obviously desirable that officer cadets should be exposed to the practical operations of the Army on which they were receiving theoretical instruction, time available for the short courses limited such activity to short visits to local schools for demonstrations. But once the 12 month course widened training horizons, extended visits to interstate schools and units were introduced, augmented by a variety of tours, excursions and sporting events. These visits were designed to provide demonstrations of the practical employment of the arms of the service: beginning with a lightning visit to the Armoured and Infantry Schools at Puckapunyal to let cadets see a wider range of support weapons, this was extended to include the School of Signals at Balcombe, with the following year artillery and engineer demonstrations included in the Puckapunyal leg. Advent of the long course allowed two series of demonstrations, the existing one for infantry and armour, and Sydney for artillery, engineers and ordnance, while some local industrial tours were arranged to a succession of plants – oil, paper and motor vehicles. By 1957 these tours had settled into a broad coverage: the units visited varied according to the time of year and availability, but armour and infantry weapons, fire direction and the RAASC School were covered at Puckapunyal, signals at Balcombe, army health and first aid at School of Army Health Healesville, while the Eastern Command tour, via Canberra for sport at RMC and visits to the War Memorial, included the School of Military Engineering at Casula, an infantry battalion tactical and firepower demonstration, an artillery unit at Green Hills range, and a look at 2nd Base Ordnance Depot and 2nd Base Workshops at Moorebank. While much of these demonstrations consisted of looking and learning, as much as possible was ‘hands on’, including artillery, mortar and tank fire direction.

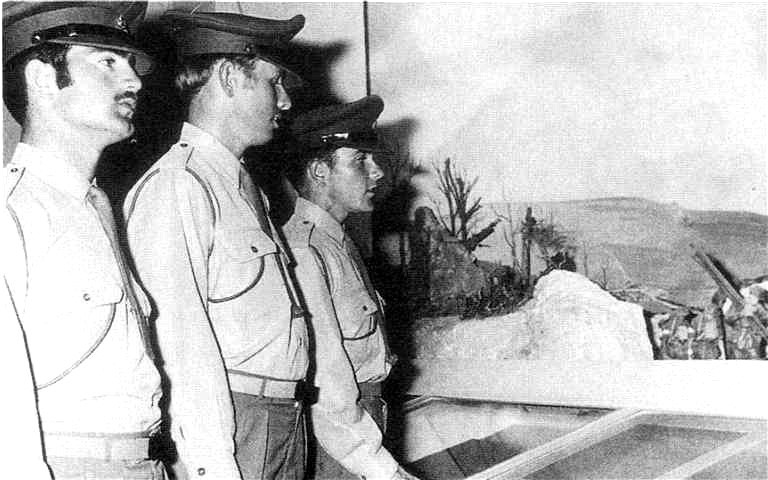

Hands on experience in gunnery – Holsworthy 1955

Good instructors always provided realistic experience so that budding officers had an appreciation of the effort and problems associated with providing support, whether it was building bridges, making roads, recovering bogged vehicles, loading ammunition on and off trucks or making a grenade range.

Artillery instructor Capt R.M.C. Cubis ensured cadets understood the implications of firing a 25 pr gun in the upper register as a howitzer by having them dig a pit for the trail. Lessons like these and directing the fire of guns last a lifetime, which shows how effective such instruction can be.

OCS Scrapbook 1955

Things changed from 1963 as the army became committed to the Vietnam war cycle when recruit and technical training of successive national service intakes, preparing units and individuals for rotation, and maintaining the force overseas, absorbed most of the attention and resources available. Demonstration visits for OCS reverted to Victoria, Puckapunyal again the focus, with less scope to be found in the limited units there. It was not until the second half of 1969 that the Eastern Command tour was resurrected, and this was cancelled again two years later through economic strictures, though a visit to Bandiana was added to cover the ordnance and workshop units there. Reinstated again, it became a standard element of the course programme, though an increasing financial awareness after the fairly unrestrained Vietnam heyday meant that more thought was given to coordinating demonstrations for the various colleges to ensure that the scale was enlarged and the cost minimised (2).

Portsea’s visits and demonstrations were by no means unique. Similar activities were scheduled for RMC, the Staff College, and after its inception in 1970 the Joint Services Staff College, as well as other interested opportunity groups. It took some time for this substantial multiplication of effort to sink in at Army Headquarters but it was finally realised that the diversion of time to a procession of such demonstrations each year, and the cost of ammunition involved, warranted a combined activity with acceptance that its timing might not be entirely convenient to all the academies concerned. It commenced with OCS going to a combined artillery demonstration at Holsworthy in 1972 after the previous year’s cancellation, and was continued with as many of the colleges and groups, including the WRAAC OCS and New Zealand OCS when it was opened in the late 1970s, but the grand concept of one all-in super demonstration foundered on the rocks of diverse timetables for the many institutions involved (3).

Cultural tours – Sydney and Canberra 1979 and 1974

Kings Cross was the magic word when the demonstration tour to Sydney was on the agenda. A weekend with accommodation provided meant that all that lay between the students and achieving whatever their hearts desire might be was cash. Demonstrations in artillery, engineering and infantry were useful if not absorbing to all but the few who are interested in nothing but self interest, and the evening entertainments in messes and downtown Sydney made a very acceptable if trying package.

The junior class had its own cultural tour, which settled down to a double of Canberra and Sydney legs. Unfortunately the imagination of some organisers in including a round of public buildings tended to blunt interest. While the War Memorial might attract RD. Edwards, N.E. Cunningham and J.D. Eastgate, the appeal of the National Library for those not into research is slight. Again thoughts turned to the flesh pots: tours of buildings and factories were interludes to be endured between the evening entertainments.

OCS Scrapbooks 1979 and 1974

These visits also provided a recreational component which gained it the sobriquet Cultural Tour, leavened as they were by visits to the Opera House, Rocks redevelopment and industrial works, the WRAAC OCS on the side, and leave in Sydney introducing those who needed it to Kings Cross. They also introduced any not previously so exposed to the benefits of military travel, the slow RAAF aircraft and interminable waits after unnecessary early arrivals at terminals, and the pleasures of long distance train journeys as sitting passengers, although many had experienced the latter in their original move to Portsea; but at least slow aircraft were better than army buses which broke down, which was long a standard hazard for travel on exercises and tours. Not that the demonstration tours were the only ones, or provided the only opportunity for culture. Starting with June 1973, the junior class had its own standard six-day outing – the cultural and industrial tour – to occupy part of its mid-year break, visiting Canberra to examine government and view such public buildings as Parliament House and the National Library, and gain an appreciation of Australian military background through the War Memorial, then to Sydney for industrial visits; for those inured to such sights the main benefits were the camaraderie engendered, and especially the evening entertainments (4).

Travelling

Bus travel

Map reading exercise 1954

Army buses in earlier days were notorious for breakdowns. Most were of a reliability which was not improved on by their age. Apart from the ones which took them with unparal1eled reliability from Spencer Street to Portsea, a bus trip had many downside possibilities, as well as the discomfort and boredom of longer trips in buses designed for suburban transit rather than touring.

Army buses in earlier days were notorious for breakdowns. Most were of a reliability which was not improved on by their age. Apart from the ones which took them with unparal1eled reliability from Spencer Street to Portsea, a bus trip had many downside possibilities, as well as the discomfort and boredom of longer trips in buses designed for suburban transit rather than touring.

When a bus became bogged or broke down, it was in all probability on the return to the School before leave or some other inconvenience, which meant hours waiting for an alternative or recovery. It took until the late 1960s for the rediscovery of the technique used by the Army from the early 1900s up to World War 2 to be reinvented – hiring commercial coaches.

OCS Scrapbook 1954

Road movement 1969

Air movement 1970

When the army stripped its own budget in the late 1950s to help pay for the acquisition of 12 Hercules transport aircraft for the RAAF, a new era of troop movement emerged, with purchase of Caribou light transports as well. With these assets, the RAAF found some even for Army support, and indeed eventually became anxious to provide it to exercise their pilots.

After a successful transfer by air from Puckapunyal to Yarram for final field training in November 1970 it was suggested that a tactical transport airstrip be built in the Nepean defence reserve, though this proposal was too ambitious even for the then current air mobile obsession within the army.

OCS Scrapbooks 1969,1970

Field Excursions

At the very core of ensuring that the training objectives of the course were met was the confirmation of theoretical instruction by practice in simulated conditions which were as close as possible to the real thing. This applied in particular to minor tactics but also embraced a whole range of other activities in which the potential officers would shortly be involved: planning and organising movement, planning and setting up camps, planning and executing exercises. In the extended period where this was practised OCS graduates had a practical head start over RMC colleagues who had to learn the hard way on the job. Another benefit accrued from the curtailment of tours to the Sydney complex was that, although the demonstrations may not have been as slick, much of those of the 1950s and 1960s were provided by the CMF units of 3rd Division, and cadets were able to see those units operating in the field in a competent manner, observe and direct the fire of their heavy weapons, and gain an appreciation not only of their capacity, but also of the wide range of units on the order of battle of the army’s reserves (5).

The Point Nepean close training area was found to be very adequate, but there were no classification ranges, requiring a pilgrimage to Williamstown until the Austfire range was installed by cadet labour in 1962; short bivouacs were introduced at nearby Flinders and Langwarrin for variety. Then the combination of an extended course and the sameness of the Defence reserve sent the School further afield to Puckapunyal, Healesville, Yarram and back to the Puckapunyal state forest areas to provide the variety of terrain and vegetation appropriate to the doctrine of the day, allow field firing and also to rest areas becoming degraded by overuse. Another incentive for the Yarram area was the hope that its coastal winter climate would be kinder than that in central Victoria, but such things are relative, the veterans of Mullungdung state forest having tales of the cold and wet equally as harrowing as the ones of those who experienced Healesville, Broadford, Gembrook and Taggerty. In this vein, various commandants angled to get to warmer climes as RMC had since 1955, but it was not until very late in the piece, when amalgamation of the colleges was on the horizon, that OCS was permitted to go through the Land Warfare Centre at Canungra and the Jungle Training School at Tully, together with the cultural side-benefits of local leave (6).

Cadets approached these periods in the field with mixed feelings. A break from the Portsea routine and regimen was always attractive, with outdoor activities preferred to trying to keep awake in classrooms and studies, but there was a downside to field training with exertion, vagaries of weather and ever-present assessment, for it was here that the latter presented its greatest potential, away from the artificialities of barracks life. From short navigation and patrolling exercises for leadership practice, to final exercises where some cadets’ final survival lay in the balance, there was an underlying pressure to perform against an unseen enemy – the assessment form carried by all instructors. Names of exercises varied but their overall nature did not: Nascent Leader, Flying Wedge, Rock Wallaby, Final Fling all evoked the mixed feelings of anticipation and apprehension, though the aftermath for most was again mixed feelings of relief and achievement. Commandant Col G.D Burgess in the early eighties found that he had to turn the assessment system on its head, returning training as the primary function, with assessment a necessary adjunct, rather than the reverse which had progressively taken over in the search for better ways of evaluating performance. However the latter need persisted as did the apprehension for some. To those on secure ground, the exhilaration of exercising command weighed evenly with the vicissitudes of an unkind climate and sleepless exertions (7).

Field Training

Demonstration

Puckapunyal 1981

Puckapunyal was a noted locale for demonstrations. In the 1950s, wartime carryover stocks of 25 pr and 4.2 inch mortar ammunition enabled 3rd Division to lavish some of it on annual firepower divisional shoots of its three field regiments and light regiment. In later years, as the equipment of the services improved, OCS was able to take the benefit of a wide range of armoured, infantry, artillery and air firepower displays.

With the introduction of new weapons of different calibre, new ammunition had to be procured and the costs borne by annual defence budgets, resulting in more economical demonstrations, the idea of a giant annual one for all colleges foundering on the difficulty of coordinating programmes.

Photo: D.N. Thornton

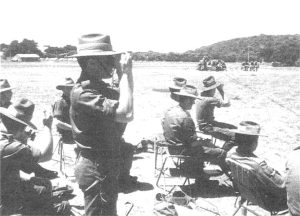

Mortar fire direction

Jarman Field 1984

The training programme included direction of fire support weapons – tanks, artillery and mortars. The first was undertaken at Puckapunyal with 1st Armoured Regiment, initially with Centurion then Leopard tanks; the second was either at Puckapunyal with a 3rd Division CMF regiment or a regular battery at Green Hills near Sydney. Mortar training was similarly undertaken with a CMF or regular unit on the demonstration tour of the time.

As a simple economy measure, subcalibre devices were used for initial local training, providing a similar pattern of fire sufficient to practise direction and without the need to travel afield. Observing fire are M.H. Cooper, A.W. Brunton, D.W. Caldwell, R.J. Dempster, G.D. Faulkhead.

Photo: D. W. Caldwell

Eating in the field

Puckapunyal 1959

Some vestiges of civilisation were maintained during demonstrations and weapons practices, A. Nicholson, R.M. Kelly, D.J. McLachlan, M.G. Holton, N.W. Spencer eating off field service tables and forms as an impromptu mess. Cooking by Fowler stove, an effective if primitive field cooker, was a little ahead of the World War 1 trench fires.

For field training the Wiles mobile trailer-mounted kitchen was able to provide adequately cooked meals, and these two old but effective equipments remained until replaced by the gasoline-fuelled American cookers.

Photo: D.J. McLachlan

Other Excursions

From the first course the School was involved in external ceremonial activities, with the annual Anzac Day commemoration at Sorrento. The first real involvement was in lining the streets during the Queen’s 1954 visit to Melbourne, followed two years later by cadets carrying the national team placards during the opening and closing ceremonies for the Melbourne Olympic Games. In the Queen’s visit of 1963 the COC paraded in the Canberra review of troops, and in 1968 received its colours from the Duke of Edinburgh at South Melbourne; in the 1977 armed services jubilee the colour party joined in the review of troops in Canberra. An awakening of national self recognition in the 1970s saw some attention being paid at last to Australia Day, and it became the annual practice for OCS to provide a guard for the ceremony at Sorrento (8).

A major foray away was for the visit by the Head of State in 1963, when a parade of the officer academies was held at Manuka Oval Canberra.

The cadets of the Royal Australian Navy College, the Royal Military College, the Officer Cadet School, and the Royal Australian Air Force Academy put on a vintage performance, as was their wont, with the OCS contingent passing the Queen on the saluting base, followed by the RAAF cadets. The colour was that of RMC, OCS being still five years away from receiving its own on the next royal visit..

OCS senior class spent a week in Canberra preparing for the parade, a welcome break away from Portsea.

OCS Scrapbook 1963

Sporting competitions provided a welcome reason for getting away from the School. For the great majority to whom sport was rewarding and the entertainment afterwards a pleasure, short and long excursions were equally welcome, outweighing the often uncomfortable and dreary time in transit by bus, train or cargo aircraft. These escapes even to Portsea oval in the early days got away for a time from the rigid discipline and constant work schedule on the campus and, as they extended further to the other service colleges and Melbourne sporting competitions, became significant recreational and recuperative factors. Demonstration and cultural tours usually included the opportunity for at least rugby and hockey matches on the side, and the institution of the inter-service athletics and swimming meetings enabled regular additional trips to be made to Point Cook, Jervis Bay and Duntroon (9).

Adventure training Mt McKenzie – Cameron’s Corner 15 June 1983

Providing an opportunity for local and overseas cadets to see another side of Australia and to organise and execute some minor operations with a strong element of the unusual, adventure training was open to cadets during their term breaks.

2 Platoon spent a week covering a zinc mine at Broken Hill, Sturt National Park, visiting a station, opal mines at White Cliffs and the tri-border comer. Not all just touring, the cadets were practised in driving and servicing, communications and navigation, as well as organising under the supervision of assistant instructors. They had the chance to entertain and be entertained by the locals, the New Zealand cadets also putting on a hungi for the latter.

RMC Archives

Another escape was found in the idea of adventure or adventurous training which was taken up from the British Army by an Australian Army short on direction and real activity after Vietnam. It was aimed at providing opportunities for challenging activities which would promote initiative, self sufficiency and leadership; in fact a pair of British army officers visited Portsea in 1964 during such an activity. It might well be imagined that Portsea would have been failing in its role if the normal syllabus was not substantially directed to those ends, however it provided the School, always hungry for more time, with the opportunity to steer some of the course breaks towards quasi-course activity, as well as providing students without anything special to do with stimulating experiences and sightseeing: it had been found in earlier courses that some cadets were at a loose end during breaks, some even setting up camp at Pearce Barracks. Expeditions were arranged using service resources as much as possible to such ends as abseiling on Eildon dam, skiing and mountaineering from the ANARE lodge in Tasmania, and visiting the outback at back of Bourke and Broken Hill to Cameron’s Corner. Encouraging cadet initiative, leadership and organising skills, as well as expanding their horizons, these provided an economical and rewarding experience for the groups which took advantage of this outlet (10).

For the overseas cadets something special came to lie in wait. Sorrento Lions Club sponsored an annual tour of Western Victoria covering Bacchus Marsh, Sovereign Hill at Ballarat, living on farm, Bendigo and home. Not all the eligible students were wrapped in the idea of four days on the road meeting the locals and soaking up local culture and history, so to avoid the embarrassment of mass defections it was made compulsory; in consequence the participants also loaded enough refreshments to soak up and so ameliorate the pain. Most of the complaint came from New Zealanders who usually had something else in mind and were less appreciative of the Australian scene than were those from different cultures; it was but small sacrifice for them to make (11).

Cadets in general were diligent avoiders of sacrifice if this could be achieved with a minimum of pain. In any establishment where leave of absence is routinely restricted there will be unauthorised absences as a matter of routine and, as was the early case, if drinking is embargoed, ways and means will be found. The reasons for absences at Portsea were as varied as cadets’ needs. In the restrictive days many were for the purpose of visiting hostelries near and afar, others for assignations or married cadets braving the tides along the beaches to get home and back; some were to meet relatives and friends, cadets O.M. Evans and P. Costello concealing a car outside the gates and escaping to pick up graduation partners from the airport (12). The range was endless, and many of the lesser thought-of cadets would have had dramatically increased leadership marks for initiative had these escapades been assessed for that purpose. Unfortunately where they became known to a humourless and unappreciative hierarchy the assessment was in the form of the scale of punishment to be inflicted.

Involuntary Visits

There was another area in which the School was not completely in control of visits away. The clause in the initial agreement of the School’s occupancy of the Portsea Quarantine Station requiring vacation within 24 hours in the event of a quarantine emergency was tested by the arrival of Strathaird in mid-August 1954 with smallpox aboard. OCS was advised during the previous week and was able to make a planned exit from the Quarantine Station two days before arrival of the vessel. As only the cadets’ and other rank mess and accommodation were required for the quarantined passengers, much of the facilities was simply secured and left, but the cadets and staff had to take all their belongings, a locker and wardrobe with them. Training was suspended on 12 August to effect the move of the cadets to Franklin Barracks and staff to Pearce Barracks, the former being fortuitously between holiday camps; the cadet area was clear by midday. This quarantine period lasted from 14 to 21 August, and things went so smoothly that the commandant was able to boast of only four periods of instruction lost, and these being made up (13).

Franklin Barracks – August 1954

Moving in at short notice, the cadets each brought their effects and a wardrobe, the whole move taking four hours. It was then immediately into normal periods of instruction, with the four lost periods to be made up as well.

It is apparent from the interior of the building, which was designed to nineteenth century barrack room standards, that the School had a lucky escape in gaining the quarantine buildings and then retaining them, making the inconvenience of the readiness to move and the two actual moves well worth the effort.

OCS Scrapbook 1954

A second evacuation was initiated by the Deputy Director of Health phoning commandant Col D.R. Jackson at 1215 on Sunday 14 April 1957 for a suspected smallpox case from the Stanvac Pretoria. This advice came at a distinctly awkward time with just a small duty staff available, but as the initial requirement was only for clearance of the RAP, sergeants mess and other ranks accommodation buildings which were adjacent to the isolation hospital, preparations to provide the ejected with emergency accommodation proceeded, with some personnel recalled to assist. However the Health requirements escalated during the afternoon, first adding the Other Ranks kitchen, canteen, QM, weapons and ration stores and transport lines; then later evacuation of the whole area was invoked, with the suspect patient to be disembarked at 1000 hours the following morning. That such a total clearance for an initial single suspected case should be invoked when State isolation facilities carried multiple infectious cases in a small controlled area says something of the desire of the Commonwealth Department of Health, while maintaining generally cordial relations, to confirm its authority over the area and justify retention of the facility, even to the extent of requiring clearance of the area in considerably less than the 24 hours notice under the occupation agreement.

The evacuation plan was invoked, but to Franklin Barracks rather than Pearce Barracks, as the loss of the 12 temporary training huts had not been anticipated and made that plan impractical. An advance party was at those barracks by mid afternoon, the main body of living-in staff arriving by early evening. Completed handover of the entire Station was effected at 1210 hrs the following day, a full evacuation within 24 hours of a partial evacuation being demanded, to ensure that there would be no excuse for the backbiting which followed the previous evacuation three years earlier, in this case the Deputy Director expressing both satisfaction and surprise that the apparently impossible deadline had been met. The fortuitous availability once again of Franklin Barracks between Lord Mayor’s holiday camps rescued the School from an awkward training problem, allowing the Commandant to report that loss of training time in the three weeks away was confined to the one morning of the move out which would be able to be made up – at the expense of students’ scarce free time (14). However the evacuation plans obviously had to be reviewed, and although Pearce and Lonsdale Bight once again came up for consideration, a tented camp at Puckapunyal was settled as the final solution, and one which was tested during the School’s first field camp in 1957 (15). Thereafter, as OCS’s occupancy became entrenched by agreement with Health, later isolation problems were met in a much more circumspect way with a fenced off isolation hospital built at the extreme west of the area. As activity tailed off almost completely, the Bungalow was used for individual cases, which simply meant closing the road leading into the Commandant’s house and Quarantine Officer’s quarters.

Final Trips Away

Leaving the School finally took many different forms. The hoped-for one for most was to graduate and, commissioned, move off to leave and a first posting: a week of festivity and ceremony, then the ultimate relief of getting through the course and off to the real world, though the harsh reality was that this was postponed by attendance at their corps school for technical training courses of anything from six weeks to two years, depending on the era and corps. For some there was the bitterness of last minute failure which reflected as much on the School as it did on the individual, while others had left much earlier for a variety of reasons. The physical activities during the course took their toll – in the gymnasium, on the sporting field, in the rigours of the simulated war of field training, and the normal hazards of living for active young men and women. For those unable to make a recovery to full fitness and those who lost too much of the course it was the army’s loss as much as theirs when they had to leave, though if at all possible any who could make a comeback were allowed to repeat a semester: D.J. McLachlan had a fall which broke his pelvis and was permitted repeat, surviving to become the first graduate to reach general rank. As adjutant Capt P.W. Pearce expressed it to departing injured ‘you go away with the satisfaction of knowing that you gave it your best shot’ (16).

Another group comprised those who left of their own volition, finding that they had simply made the wrong choice of career. Just as the second Field Marshal of the Australian Army Prince Phillip had seen one of his sons reject the military life for the theatre, so a steady trickle of cadets came to this realisation and, although their joining instructions said that they would be required to complete the course unless removed, it was to everybody’s benefit not to persist with anyone who was unsuited or disaffected, again in Pearce’s words ‘you realise there is a better life for you outside rather than in the army’. Others suffered temporary lows, many salvaged by assistance of guidance officers, sympathetic instructors, the RSM, chief physical training instructor, and above all by their classmates, though the latter were also known to accelerate a departure decision by those they believed not up to the course or life as an officer. Finally there were those who ‘beat the BOS’, knowing that their results meant removal as failures, resigned to leave as their choice rather than suffer dismissal (17).

The Board of Studies and its predecessor committees were the avenue through which commandants came to the decision to recommend removal of a student other than occasional dismissals for gross misbehaviour. Cadets were warned, counselled and assisted after the BOS found that they were at risk, but the final axe eventually came for a substantial proportion unable to make sufficient academic progress or unable to develop an acceptable capacity to become an effective leader. A usual practice had been for the commandant to remove a cadet and inform Army Headquarters, but with the sensitivity of overseas students, some of them from highly placed families, the Adjutant General (later Chief of Personnel-Army) required that the decision rest with him. An incoming instructor in 1972, Capt R.L. Sayce noticed something different ‘from his day’ – cadets who had been effectively dismissed were now hanging around the campus in civilian clothes awaiting confirmation, a misery to themselves and a morale depressant for the rest his class. A system of verbal agreement from Canberra was arranged and an instant procedure of advice, counselling and removal instituted. This resulted in disappearances of class members, but was preferable to the lingering delays; the black-humour habit arose of the cadet duty officer playing a current Queen hit song ‘Another one bites the dust’ over the loudspeaker system on the evening of such departures (18).

There remained one other group which made the final trip away. After the graduates of the class of December 1985 had departed, the junior class headed for leave and reassembly at Duntroon where they had a year remaining. While this extra time was disappointing after seeing their seniors escape after 12 months, these were the grounds on which they had entered Portsea so there could be no complaint. For the final graduating class, admonitions from the RSM that repeating a term meant in fact another year was a great incentive to passing straight out, resulting in none being backsquadded, but one of the junior class had more than his fair share of the road to a commission: B.A. Jennings who washed out of RMC after three years, completed his degree at University of New South Wales, entered Portsea for six months, then back to RMC for another year. This class entered Duntroon as the only occupants, the remaining class there having gone over the hill to the Australian Defence Force Academy. They were allotted the appropriate cadet ranks on leaving Portsea and became temporarily Duntroon’s Second Class, being six months into the new 18 month course. When the incoming new entrants moved into Duntroon in March after completing their induction camp, the ex-Portsea Second Class became First Class, so setting the OCS imprint and ongoing tradition on the old-new single army college (19).

Junior Classes Moving to RMC

Junior A Class

December 1985

R.K. Wyett P. Daniels M.G. May W.R Hanlon R. Fullerton R Northrup R.C. Parello M. Dawson D. Barlow C.M. Goddard

T.K. Williams G.J. Ducie P.C. Gates I.J. Afruns P.D. Galea A.R Clements G.A. Ackhurst A.B. Cook M.A. Seeley O. Oksap

P.J. Kennedy I. Nisbet D. Nichol M. Faulkner M. Phillips L.M. Barnes J.K. Walters Ong Chong Lin S.J. Roberts

B.A. Stevenson C.M. Lumley N.A. Withycombe S. Crafter G.R Baker A. Kenman A.J. Anetts J.T. Terrie N.G. Schwebel

Junior B Class

December 1985

D.J. Campbell R.L. KIuckhorn G. Carter G.D. Reiss T. Stevenson M. Doyle D.M. Luhrs A.R Cassie M.A. Phillips H.L. Worthington

G.T. Ford S. Hardy M. Schmidt P.M.A. Quaglia G.F. Stow T.L. Fairbairn J. McMillan C.A. Mitchell J.O. Rieck K. Mason A.C. Shegog

M.A. Smith D.J. Cullen D.W. Townley G.J. Hooker K. Grimley T.J. McNamara P.M. Quilligan K.G. Webb B. Sloan S. de Forest

P.J. Thomson E. Hesingut R.P. Burdock F.J. Watts S.C. James B.A. Jennings A. Armstrong M.J.P. Ducie A.R Mildred Absent: A.E. Morrison

Photos: KS. Fraser

References

- The paragraphs in this section epitomise AA B2453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Reports 1952 onwards.

- AA B2453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Reports 1952-74; OCS Journal June 1971, p45; June 1975, p80; December 1985, p83.

- AA B2453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Reports 1972 onwards.

- AA B2453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Report of 7 August 1973; OCS Journal December 1978, p46.

- AA B2453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Reports passim.

- AA B2453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Reports passim; OCS Journal June 1985, p30; December 1985, p84.

- AA B2453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Reports 1973-4.

- OCS Journal June 1972, p40; June 1985, p31; OCS Scrapbooks 1963, 1977.

- AA B24531 I R723/1/1 OCS Reports passim.

- AA B2453/1 R723/1/1 OCS of December 1964; OCS Journal December 1982, p28; RMC Archives R852/7 of July 1983; AA B2453 1 I R852/2/2 of 18 July 1984.

- AA B2453/1 R133/7/17 Brief on Orientation and Entertainment Foreign Military Students of 26 March 1974; OCS Journal December 1981, p19.

- Letters F.D.L. Greenway, O.M. Eather.

- AA B2453/1 R723/1/1 OCS Reports.

- Nepean Historical Society; AA B2453/1 R723/1/1 of June 1957.

- AA B2453/1 6/2/6 of 11 June 1952, 14 December 1955, 16 July 1957, 1 August 1958, 12 February 1959; OCS Administrative Order 2/57 Evacuation in the Event of Quarantine.

- Video An Officer and a Lady.

- Video An Officer and a Lady; Letters G.J. Crowley, O.M. Eather, R.L. Sayce.

- OCS Standing Orders; AA B2453 1 I R5730/1/3 of 4 October 1976; Letters RL.Sayce, P.M. Perrin.

- An Officer and a Lady; Interviews B.A Jennings.