3

Changing Entrants

Portsea had started as an avenue of entry to the main combatant arms of the service – Armour, Artillery, Engineers, Signals, Infantry and Army Service Corps. However this was widened to include progressively Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, Ordnance, Intelligence and Military Police to flesh out those corps as increasing technology and complexity within the postwar Army had meant a broadening of specialist categories of officers and both a numerical and proportionate increase in their numbers. Further avenues to commissioning had developed when qualified civilian pilots, surveyors and teachers were allowed direct entry to overcome the twin problems of shortages and a reluctance of professional candidates to endure an arguably unnecessary four year course at RMC or one year at OCS, and indeed in recognition of the adequacy of abbreviated officer training to fit them for limited employment in their field without the breadth and depth required for general service officer entrants.

These were initially trained through expedient short courses at various army schools and then at Scheyville from 1965 until OTU’s closure on the suspension of National Service in 1973. As the numbers in these categories could not justify a separate short course, and the climate had not yet become right for an amalgamation of these courses with the similar one at WRAAC OCS, this closure left no alternative but to include them in the Portsea regime. That they would be undertaking a course designed for mainstream officer candidates was now accepted as it was becoming usual for adequate specialist officers to spill over into non-corps administrative and training positions when they developed later in their service: as the career path within their speciality tapered, they became available for wider employment in an army hungry for and willing to use their talents in general administrative positions. This in turn required a broader training of candidates as general service officers rather than the previous direct entry to commissioned rank hitherto relied on.

WRAAC OCS – Georges Heights, 1959

Also a product of the postwar officer shortage, the School was opened at Mildura to provide extra officers, mainly in the personnel area. In keeping with the times, there was no sense that women belonged in the army as a natural part of it – rather the wartime idea that they released males for field duties remained until the late 1970s.

The WRAAC OCS was closed in 1983, absorbed into OCS the following year. The entrance gates were dedicated to Colonel K. Best, founding Director of the WRAAC in 1951. They were reerected at Duntroon on 6 November 1994, 35 years after their original opening, as a reminder of one of the streams now embodied in the Corps of Staff Cadets.

WRAAC Association (National)

Other special categories had presented themselves, initially female officers who had been catered for very early by establishing the WRAAC Officer Cadet School with a six month course at Mildura then Sydney, still held to be a suitable means of qualifying officers not destined for field duties. Then expansion to meet the post-1963 growth of Regular Army units required for the duo of training National Servicemen and cycling units through Vietnam brought the same pressures on officer numbers and production as had that of the early 1950s. OCS and RMC were expanded to the limit of their facilities and each tasked with producing 140 officers annually, while the Officer Training Unit was established at Scheyville, south west of the Blue Mountains, to conduct 22 week courses to prepare candidates from the National Service intakes for short service commissions. While OTU output met the need for short term and specialist officers in a parallel to OCS’s early short courses, there was still a shortfall by 1972 in the numbers of officers required to maintain the 45,000 man Regular Army and also provide cadre staff to support the CMF structure, even though output of the three academies was augmented by the expedients of employing CMF officers on full time duty and extensions of short term commissions and retiring ages. In consequence it was decided to enlarge the output from OCS by establishing a wing at Scheyville under the aegis of OTU, using its facilities and instructional base as an immediate solution to what was hoped to be a short term problem (1).

Officer Training Unit Final Graduation – Scheyville, 1973

National service in 1964 brought a liability for officers different from its predecessors in some major aspects: it was for two years full time service, they were available for immediate service in Vietnam, and they were 20 year olds.

Officering the doubled army could not be met by OCS and RMC and from earlier wartime experience, the talent in the ranks of the National Servicemen could not be passed over. OTU became the major source of officers, producing 1,802 from 1965-73, more than the others combined.

CGS Lt Gen M.F. Brogan takes the salute with commandant Col K.P. Outridge; the last OCS Wing was also on parade.

Photo: K.P. Outridge

This wing was to operate on a one off basis, but was continued for two intakes more and might have continued indefinitely except that, with the suspension of national service, withdrawal from Vietnam and wind-back of the Regular Army, the need for officers was reduced and OTU closed. Not that this wind back meant a substantial reduction for OCS as the flow of overseas students continued and it also became the only feasible avenue for handling the short course special entry candidates for survey, aviation and a smattering of other corps. The wastage of short commission and CMF full time duty officers also added to pressure to maintain a high level of output.

Expansion

From the mid-1950s, when the immediate officer shortage had been overcome, to the early 1960s the School had been in something of a period of low level activity. While it had been retained in recognition that the academic requirements at Duntroon were denying the regular officer corps valuable talent of a practical and necessary kind, both institutions were experiencing difficulties in attracting sufficient suitable applicants to meet their targets; indeed both OCS and RMC in one of those years, to meet even a much reduced intake, accepted entrants which a psychologist assisting the selection procedure described as half being below the usual minimum standard. The nadir for OCS in June 1961 saw a graduation of nine Australians with nine New Zealanders and one Malayan; commandant Col J.G. Ochiltree, visiting Army Headquarters in Canberra during this period, was asked by a contemporary how things were and replied ‘still running a school for overseas countries’. It took the impetus of the new national service scheme of 1963 and the war in Vietnam to create a demand which peaked in 1972-73, on the eve of the suspension of national service and withdrawal from Vietnam, with successive half-yearly graduations of 99, 92 and 95, of which 73, 61 and 74 were Australian. It was the only time that the 1963 target of 140 per year was close to being met, although at this stage Army Headquarters had reduced the annual target to 88 in recognition of the tapering requirement (2).

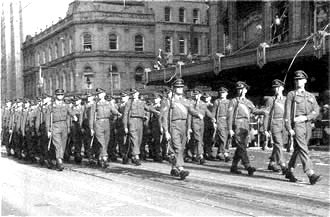

Anzac Day – Melbourne, 1961

The Company of Officer Cadets took part in Melbourne’s Anzac Day march, led by CSM G.E. Vickers and Sergeants B.C. Donald, A.J. Campbell and J.M. Bensley. The COC was not numerous at that stage, accentuated by marching six abreast.

While the June 1957 class graduated the all-time overall lowest of 15, 11 were for the Australian Staff Corps compared with only nine of the 19 from June 1961, the rest being one from the Federation of Malaya and nine New Zealanders.

This low local attendance changed when the Vietnam War stimulus and improved conditions of service began to produce higher levels of interest in the course. This was matched by an AHQ target of 140 per year, vastly above the less than 40 average of previous years.

Photo: D.N. Maddocks

Throughout this period, the average annual output of Australian graduates was 91 from an average intake of 119, a shortfall of 49 accentuated by a wastage rate of 28 percent, both of which were a source of ongoing concern for an Army stretched in meeting operational, training and administrative commitments unprecedented in the post-World War period. The structure of the School had been expanded accordingly through a construction effort and training and administrative staff increases but even the major building programme of the 1960s had underestimated the demands made on the School at its peak, with some cadets once again forced to share rooms designed for one in comfort. A prospective student population of 240 prompted successive commandants McDonagh and Butler to struggle for remedial action but with the prospect of a Tri-Service Academy reducing army officer training to one college, the Military Board in 1973 approved this to be located at Duntroon. Any hopes of a major redevelopment at Portsea faded, and the School had to make do with the overflow wing at Scheyville until smaller intakes relieved the population pressure (3).

Accommodation had not been the only problem of expansion. From the small class-small staff regime which had provided an intimate instructional relationship, there had been a significant expansion followed by reconstruction of the faculty in 1966 into two wings to consolidate expertise and allow control and effective implementation of a training programme built around the two-company structure introduced the previous year to cope with the expanded numbers. This had meant not only two classes but two half classes of each to match the lecture facilities and effective class sizes, which meant repetition of tuition, added complexity of allocation of both indoor and outdoor facilities and careful scheduling of programmes. All of this did not come without a price. Combined with a progressive development of the curriculum from minimum training for regimental officers, through a broad knowledge of the arms and services, to the art and science of war, a much more sophisticated training staff had to be co-developed, with administrative staff expanded to match the demands of the operating side of the academy. As is usually the case, allocation of resources tends to lag the requirement, so while the decade of expansion from 1963-1972 was coped with by ongoing incremental improvements and improvisation, when subsequently the workload had evened out the onward development momentum continued, with an increasingly complex and layered structure which did not have an ongoing expansion to justify it (4).

Liberalisation

Major General Sir William Throsby Bridges KCB CMG 1861-1915

Migrating to Australia in 1879, he was commissioned in the NSW Permanent Artillery and sent for training in UK. After return, he became Chief Instructor at the School of Gunnery, went to the Boer War with the British Army and there evacuated to Australia medically. Rapid promotion saw him as AQMG at AHQ, Chief of Military Intelligence and Chief of the General Staff, then sent to England as Australia’s member on the Imperial General Staff.

After promotion to brigadier-general as inaugural commandant of the Royal Military College Duntroon in 1911. In 1914 he was appointed Inspector General of the Army, following Kirkpatrick but the outbreak of World War 1 saw him appointed to command 1st Division, Australia’s initial contribution. The division was committed to Gallipoli where Bridges was mortally wounded by a sniper; he was knighted immediately before his death.

The Bridges concept of officer training – rigid discipline and isolation of malleable youths had of practical necessity been modified at Portsea from its inception. The more mature student body, mostly exposed to tobacco and alcohol use and social, even married life, and its proximity to a holiday area meant that the School’s approach was more relaxed than the historical one at RMC, which even banned smoking for the junior class until 1951. However the early courses at Portsea were also forbidden alcoholic drinks and possession of motor cars, similarly relying on clandestine efforts to circumvent these restrictions when time presented the opportunity. But although it was not until the aftermath of a late-1969 bastardisation scandal at Duntroon, and an enquiry chaired by RMC graduate Justice R.W. Fox, that the subject of unnatural restrictions on basic privileges of officer cadets was brought into the open (5), a strong trend towards liberalisation had already emerged at Portsea.

Cadets Mess – Portsea, 1972

Originally a lecture room, provision of a lecture complex, and the acquisition of six Victorian Education Department portable classrooms allowed conversion to the cadets’ dining room. This was not before time as the expansion of staff and cadets to meet the training need had put a similar pressure on living accommodation.

Even with this larger area the numbers of the early 1970s put a strain on the capacity of messing facilities and staff which, if the projected intakes had been sustained, would have required a more permanent solution.

It was always attempted to make the mess as near to an officers mess as practicable for status, but also for training in etiquette and the standards they could expect in later service.

Australian Archives

This process was initiated by commandant Col B.L. Bogle, and taken up with some activism by two men with the unusual combination of firmness and flexibility of mind: incoming commandant Col J.F. McDonagh and commanding officer of the COC Lt Col J.W. Sullivan continued to reorient both the routine treatment of cadets in general and the approach to junior class training. The approach was that, in a course training officer cadets to be officers, they must learn to organise their lives to fit the military requirements without rigid regulation and supervision, so they should be able to make their own decisions on the basis of that self choice, with some appropriate guidance. This process would further develop the leadership traits of integrity, responsibility and self discipline, and eventually make the transition from officer cadet to officer the easier (6).

Cadets Recreation Room – Portsea 1972

Also a byproduct of the 1960s and 70s expansion, recreation facilities became overcrowded to the point where at popular times they became assembly rooms rather than places of relaxation.

This, plus the previous and following photos are a series from Commonwealth Department of Works to support the need for expanded facilities, but by this time Army Headquarters was revising target numbers downwards and overflow students were trained at the OCS wing at the OTU Scheyville, so urgency slipped from considerations.

As well the prospective Tri-Service Academy began to inhibit moves towards redevelopment at Portsea on the preconception that Duntroon would become the venue for future army officer training.

Australian Archives

General conditions on the campus were swung towards a normalisation of lifestyle: the prohibition on leave during the week was relaxed, and weekend leave after Saturday sport became standard; married cadets, previously given no special room for absences from the campus, were encouraged to go home when not required at the School; brief bar openings in the Cadets Mess on weekend evenings supplemented by cupboard drinking was rationalised to all evenings and weekends, with wine available at evening meals; civilian clothing was authorised after the day’s work including for night lectures; and use of private cars to go to and from duty and sports was permitted.

Cadets Mess Bar – 1972

First introduced in 1966 on a very restricted basis, its opening hours were extended in 1969 to make it a viable alternative to heading for a local hostelry at every available opportunity, and keeping hidden supplies in rooms to ward off the winter cold. Sensible drinking habits were also fostered by allowing service of wine with evening meals.

Also part of the overcrowding tableau, the photograph depicts all eight feet of bar area, required to service up to 150 members of the mess. While never intended as a leaning bar, it could not cope with the rush hours endemic in a tightly timed lifestyle.

Australian Archives

A more particular approach was given to junior class training, where a great deal of elasticity existed. The overlapping senior-junior class system adopted in 1955 was welcomed as it allowed the very substantial benefit of cross education in a wide range of social and disciplinary areas, but within this relationship lay the seeds of bullying or bastardisation from excesses in a theoretically sound way of doing business. Bullying, fagging and menial tasks were outlawed, punishments had to be recorded, with physical penalties such as press ups, doubling on the spot and cold showers declared illegal. With this much achieved a good start had been made with creating a more stable environment however the commandant’s claim that liberalisation had ‘removed any possibility of sustained bastardisation’ did not recognise the capability for bending rules in a system where junior students quickly realise that compliance and acceptance of routine indignities is the easiest and safest way, and this in turn inculcates them with the desire to pass it on in due course to their junior class; so is a culture of harassment institutionalised, and the way opened for a more vicious turn. While some members might claim that there was neither the time, inclination or tolerance for such activity in their earlier classes, and McDonagh considered the problem solved, it would have been a foolhardy commandant indeed who let his attention stray from the potential for excesses and so emulate the troubles which overtook colleagues at Duntroon (7).

Junior Class Introductory Course – Jarman Field, January 1985

An initiative of chief instructor Lt Col K.S. Gallagher, it segregated the new entrants from the COC for the first two weeks, allowing them the opportunity to get to know the ropes of army life without the attentions of their sometimes overeager seniors.

Last in a series of reforms aimed at ensuring that life at Portsea, though designed to be hard, did not become intolerable or contribute to unnecessary drop out or failure, it became a standard facet of officer induction training.

Photo: L.A.C. Norton

It was finally recognised that the attentions of the senior class in the early stages of a cadet’s struggle to cope with the new environment and the pressures of adapting to a high pressure life were too much. Chief instructor Lt Col K.S Gallagher persuaded commandant Col G.D. Burgess to institute a circuit breaker: on march in, the new boys were housed in a tented camp on the oval and given two weeks induction and basic training by the instructional staff separate from the COC. At the end of this they entered their permanent accommodation at least over the initial hump and more able to cope with the pressure-cooked routine, facing their seniors in a less traumatised and vulnerable state than on initial entry (8).

The downside of liberalisation was that pendulums have a habit of swinging too far. Capt R.L. Sayce, graduate of 1965 and returned as instructor and then adjutant seven years later, noted that the new class was not moving at the expected pace, it being customary in his day for all movement other than at drill to be at the double as a means of accelerating achievement of the level of physical fitness necessary to cope with the course. This was easily remedied but another factor was the Australian student wastage rate, which rose from the first two decade average of 22 percent to 33 percent in 1969-85, with a two year 1971-72 peak of 37 percent (9). While there could be many reasons contributing to such an increase, the attempt to allow students to self motivate ushered in an era in which commandants and staff were stretched in finding ways to avoid unnecessary losses without compromising standards: one was reversion to some of the more restrictive practices. It is a simple fact of undergraduate life that a considerable proportion of students is satisfied in doing no more work than is necessary to gain a bare pass mark in subjects other than those in which they have a consuming interest; and targeting 50 percent is a hazardous exercise leaving no margin for error. Officer cadets were no different from their university peers in this roulette.

Consolidation of Officer Training

John Malcolm Fraser AC CH 1930 – 2015

Malcolm Fraser entered federal parliament in 1955, and was appointed Minister for Army in 1996 in the Holt government during the Vietnam War. He moved to Minister for Education and Science in the Gorton government, then in 1969 to Defence, from which he resigned two years later, alleging prime ministerial interference in his portfolio. During this period he promoted adoption of the Martin Report’s proposal for a tri-service, degree-granting military academy.

He became Opposition leader during the Whitlam Labor government, engineering its demise in 1975 and becoming prime minister after the election. His government approved the formation of the Australian Defence Force Academy but, succumbing to academic pressure, not as an independent university: this underlying reason for ADFA was placed in the hands of the University of New South Wales.

Sir Leslie Harold Martin CBE FAA FRS 1900-83

Martin was a physicist who had a distinguished academic career and was variously Defence Scientific Adviser and Chairman of the Australian Universities Commission until 1966. During this time he worked for the affiliation of the RAAF Academy with the University of Melbourne, which consequently proceeded with more vigour than the long-running attempts for a similar affiliation for RMC.

From 1967-1970 he chaired the government-established Tertiary Education (Services’ Cadet College) Committee on the feasibility of setting up a college for the joint education of officer cadets of the three Armed Services. This concept of replacing the academic content of the three separate service colleges with a central university-type academy was strongly supported by then Defence Minister Malcolm Fraser. Planning proceeded slowly until it was given impetus when Fraser became prime minister in 1974.

Training Command inherited the officer training establishments on its formation in 1973 and it was obvious that the system was in some disarray. From the early seventies, when Defence Minister Fraser pressed implementation of the Martin Report recommendation for a Tri-Service Academy to take up the academic training component of the three Service colleges to overcome the large separate academic overheads, uncertainty on OCS’s longevity and development plan set in. Reduced to the special to service training function, RMC’s course would parallel that of OCS, as did the WRAAC OCS; and other direct entry short indoctrination and in-service commissioning courses continued at Land Warfare Centre Canungra and the School of Army Health at Healesville. Training Command advised OCS in January 1975 that it was proposed to conduct all these at Portsea, OTU Scheyville having closed two years earlier. The School rejected the idea of two week indoctrination courses, but could see both the merit and practicability in the WRAAC course operating at OCS in a similar way to the OCS wing having operated using OTU’s instructional and accommodation facilities at Scheyville. The 839-period WRAAC syllabus was limited and slow tempo compared with the 2,570 period male cadet one, but the bulk of the non-field component was well matched and offered ample scope for combined tuition. However the concept of amalgamation was still elusive, with separatist ideas of the female students and instructors living at the WRAAC Barracks at Mt Martha 40 km away. The spirit was lacking for such a venture without the pressures of necessity which had forced the Scheyville excursus, and considerations in Training Command wandered to another scheme of six week indoctrination courses for medical, dental, survey, education, psychology, catering and nursing officers and chaplains which may have seemed a tidy way of dealing with a messy problem, but was quite out of character with the content and tempo of OCS instruction. It failed on that basis just as the WRAAC one did because it was before its time (10).

After Malcolm Fraser returned to office as Prime Minister in 1975 he was not pleased that his fix for Defence officer training had slowed and stalled, reactivating the Tri-Service Academy project with a 1977 government decision to proceed with its planning and construction, estimated to be in operation in the mid-eighties. This imperative provoked a more positive response, with a decision to centre army officer training at RMC from the opening of that academy, and as a preliminary its progressive standardisation and consolidation at OCS in a staged programme to bring all instruction into line ready for the final resolution. The WRAAC OCS course was accordingly extended in 1979 to 44 weeks as a preparatory move and the upper age bracket for OCS extended to 26 to allow absorption of the in-service qualifying and appropriate direct entry courses; but it was only in the final year that the Officer Training Wing of the WRAAC School was closed and OCS took on this instruction. It was by no means a rapid progression to amalgamation, the process tending to fill in the time up to the opening of the Australian Defence Force Academy (11).

New Faces: S.C. Naylor and R.E. Johnson – December 1985

While canvassed for over a decade, there was no rush to take on the integration of training servicewomen in the mainstream training units. One barrier was why they should undertake field training when army policy did not permit their field employment.

It required a decision that they go beyond the role of releasing men for field employment to their filling many such positions on an equal basis, which meant that officers should match soldiers of both sexes whom they commanded. The corollary to this was inevitably their acceptance as simply soldiers and the demise of a separate corps with its own barracks, administration and separateness.

RMC Archives

Absorption

With the decision to open the Australian Defence Force Academy in January 1986, and the RMC course consequently then bereft of its academic degree content, the latter was left with the same scope and function as those of OCS: one had to go. It might have been argued that OCS should continue its function and RMC fade out, but at that stage the decision making ranks of the Army were dominated by RMC graduates, and if for no other reason than that, RMC had to be the survivor. However such a decision was not without merit on other than parochial grounds: RMC undoubtedly had far the longest tradition and national and international recognition and prestige as the senior academy equating to those of other countries’ senior colleges. While an academic suggestion that Duntroon graduates were part of the national establishment hegemony had to be overstated, there is no doubt that it was the Australian institution of international repute amongst western countries with major military academies, while Portsea’s reputation was largely confined within the Army itself and the few Asian-Pacific countries which sent students regularly to it. In consequence the Chief of the General Staff decided to merge the Officer Cadet School, with its now established female, RAAF and overseas components, into the Royal Military College with effect January 1986. Much use was made of the title Royal Military College of Australia as if it was a new term, but that had been its official title since inception, RMC Duntroon being a shortened version matching RMC Kingston and RMA Sandhurst (12).

Behind the heartburn about the loss of name and separate identity, which was inevitable, what was really at issue was the location of the RMC of A. Founding sponsor of OCS Chief of the General Staff Lt Gen S.F. Rowell had, during the time he was manoeuvring for the Portsea site for the new institution, been fending off the demands of arrogant public servants attempting to banish RMC to Mildura to allow use of Duntroon for public servant hostel accommodation blocks, the parade ground being also considered an admirable car park. The Military Board had always been alert thereafter to preempt any similar moves, and when it was apparent that there was government backing for a Tri-Service Academy, it decided that Duntroon should continue to be the site for the residual army academy. After the matter was reactivated with return of a Liberal party government in 1975 the same underlying philosophy overshadowed attempts by OCS to direct attention to selecting the best overall site available rather than the traditional one. A strong element of frustration was apparent in the fruitless attempts by commandant Col P.G. Cole to present the comparative benefits of the uncontested dedicated Point Nepean training facilities compared with the uncertainty of tenure and problems of sharing with the Tri-Service Academy in an expanding Canberra always hungry for inner city land (13).

Godfather of the Officer Cadet School Portsea, he sponsored its inauguration ‘as early as possible’ to qualify entrants who should ‘have the same qualities and standards of character and potential leadership as are required for RMC selection’.

He also fought hard to gain the site at the Quarantine Station Portsea, and made sure of both opening the School personally, and attending its first graduation in consort with the Minister for Army and the entire Military Board to ensure that there would be no doubt of its standing within the army community.

RMC Archives

The arguments fell on barren ground. While Portsea provided what was still ‘a magnificent site’, the abysmal weather of both locales was on a par, and the training facilities favoured Point Nepean and the nearby Victorian state forests, the ultimate commitment stayed with tradition and the result has proved to be at least workable. The mechanics of transfer remained to be decided: Portsea’s half yearly intake meant that the July 1985 class would still be one third through the new standard eighteen month course at the time of absorption, and would become the College’s senior class with a year ahead of them. There was in this not only an element of disappointment in the extra time involved for that class but also a considerable incentive for those in the final graduating class not to fall into a repeat which would sentence them to an eventual total of two years. At least going in as the senior class gave them the positions of cadet authority, the responsibility of carrying on the tradition, and the opportunity to mould the Corps of Staff Cadets for its future.

Augmented Corps of Staff Cadets, RMC of Australia – Duntroon 1986

With the senior class the last class from Portsea, their first ceremonial parade was to farewell and lay up the colours of the Officer Cadet School Portsea in the Anzac Chapel, Duntroon on 23 March 1986.

RMC Archives

Disposal of the site caused some heartburning. Just as the Department of Health had resisted giving up such a prime location, so too Army in its turn sought to retain it. In early 1983 when a serious review was conducted there were 17 ARA and five Reserve units for which a permanent location had not been found, as well as other units which required major works to make their accommodation adequate but with no possibility of funding in the foreseeable future. The possibilities were examined on the basis that a future occupant of Portsea would have to be selected on the relocation providing savings through consolidating functions or reducing pressure on critical training areas elsewhere. The long list of candidates was reduced to a short one of the School of Army Health, Military Police School, Junior Staff Wing of the Land Warfare Centre and 1st Commando Regiment; the feasibility study came out in favour of relocating both the School of Army Health to allow relinquishment of the deteriorating Healesville site, and the Junior Staff Wing to reduce the overload at Canungra and be near to the Command and Staff College at Queenscliff. In addition it was decided to examine the use of the ranges for Reserve and Senior Cadet units as an alternative to the competition for overused facilities at Puckapunyal and Williamstown (14).

There were of course pressures to pass the whole reserve to State control, Department of Administrative Services obtusely insisting that the Prime Minister’s 1976 undertaking to the Victorian Premier to transfer the Portsea reserve ‘when the Commonwealth’s need for the land ceases’ was synonymous with when OCS departed, and that the Commonwealth was morally bound to this course. The CGS was unimpressed with this and advised the Minister for Defence of the continuing need and the proposals outlined in the feasibility study, with which the latter agreed. The final scheme was for the School of Army Health and a small range staff to support use by Reserve and Cadet units, so the Department of Administrative Services was requested in late 1983 to arrange the transfer of the Department of Health land and assets to Defence, or at least to continue with the permissive occupancy which had existed since 1951. Administrative Services continued its ‘morally bound’ obstruction through 1984, establishing an interdepartmental working group in true Sir Humphrey Appleby style to keep the argument going. The Minister for Defence decided on ongoing defence use, with the School of Army Health taking custody on 3 February 1986 when graduate and staff member Capt K.S. Fraser, who was winding up the final affairs of OCS, left the campus (15). It was a nice turning of the wheel that a military health establishment should succeed to occupancy of the civil health and military reserves.

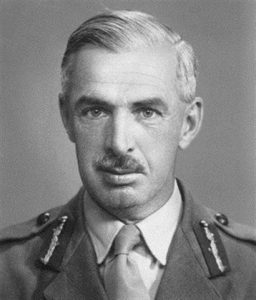

General Sir Arthur Leslie MacDonald KBE CB mid 1919-95

Born in Rockhampton, he graduated from RMC in 1939 and saw service in the Middle East and South West Pacific in 2/15 Bn. He commanded 3 RAR in the Korean War, and returned to Australia as Director of Operations, commanded PNG Command, and served as DCGS and Adjutant General.

He commanded the Australian Force Vietnam 1968-69, returned as Adjutant General again, then GOC Northern Command. He was Chief of the General Staff 1975-77 during the difficult period of the absorption of the service departments into an overblown defence civil and military bureaucracy. His final position was a Chief of Defence Force Staff until his retirement in 1979.

So ended a military generation which produced 3,544 officers: 2,826 for the Australian Army, 30 for the RAAF, 398 for New Zealand, 61 for Papua New Guinea, 91 for Malaysia, 40 for Singapore, 38 for the Philippines, 16 for Brunei and a total of 20 for Thailand, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, Cambodia, South Vietnam and Tonga (16). That generation, in which the early graduates were mostly retiring, had come to a close but there was still another generation in which the later graduates would continue to serve. The older serving graduates, contrary to the common wisdom delivered to the initial classes of no expectations beyond major, were occupying their share of the senior appointments in the Australian Army and do so in other armies, and will continue to do so throughout that second generation into the next century. They have provided a core of the armies of Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea at a standard equal to any, and also significant cadres to Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines. In the words of ex-Chief of Defence Force Staff General Sir Arthur MacDonald delivering the Harrison Memorial Lecture at Portsea on 14 November 1984 (17):

Over the years I have known many hundreds of young officers who received their training here or Duntroon. Only very rarely have I known from which stream an individual was drawn.

This was a widely held opinion throughout the Army, and just as well for both the harmony of the officer corps and the capability of the Army. This ethos was enunciated by commandant Col T.F. Cape to the 1955 graduating class, that the Officer Cadet School was not producing second class officers – there must only be one class for war regardless of the stream from which they came (18). The Officer Cadet School Portsea lives on – in its successor the Royal Military College of Australia, in its graduates serving in the armed forces in Australia and abroad, and in the memories of all those who passed through it.

Table 1 Chronology of the Officer Cadet School Portsea

References

- AWM MSS 1459 A182/R2/12 of 31 July 1967 OCS Statistics and Role; AA B2453/1 R130/2/3 OTU R133/3/1 of 19 February 1972.

- AA B2453/1 R130/2/2 of 9 February 1971.

- Table 7; AA B2453/1 R130/2/2 of 2 February 1971; R723/1/1 OCS Reports 3 February 1972, 7 August 1973.

- See Chapter 8.

- Fox et aI Report of Committee of Enquiry into the Royal Military College.

- AA B2453/1 R133/2/8 of 20 September 1969 and 4 April 1970.

- Letters O.M. Eather, E.J. Ellis; AA B2453/1 R133/2/8 of 20 September 1969 and 4 April 1970.

- Interviews G.D. Burgess.

- Letters R.L. Sayce; see Table 7.

- Coulthard-Clark Duntroon, p245f; AA B2453/1 R852/13/2 of 13 January, 28 February, 6 June, 25 August 1975.

- MSS1479 A84-11912 of 20 December 1984.

- AWM MSS1479 A84-11912 of 20 December 1984.

- AA B2453/1 RBI0/1/6 of 10 October 1978.

- Hence the RSM’s warning to cadets under warning in An Officer and a Lady; AWM MS 1479 A84/B4/323 undated 1985.

- AWM MSS1479 A84-34323; AA B2453/1 R560/1/2 of 7 November 1985; Interviews K.S. Fraser.

- Table 7.

- Wrangle C.G. ed ‘The Harrison Memorial Lectures’ MacDonald Lecture 1984.

- RMC Archives Miscellaneous OCS Commandants’ Graduation Addresses Col T.F. Cape 15 December 1955.