1

Evolution of Officer Training

Provision of officers for armies was traditionally a matter of class. From earliest historical times the leaders of communities were war leaders, from which much of their general authority was also usually derived. Indeed early civilisations in their quest for and defence of land were regularly at war, so the ruling classes were necessarily leaders in war, religion and law which in combination both constituted the body politic and were the means of organising and controlling the people (1). The non-military ruler or leading politician is a very recent phenomenon.

Training of officers is also a modern invention. While the study of military history and texts was widespread from ancient times, this was on an individual basis, with tactical experience coming from field training and campaigns, the favoured also gaining experience on the staff of powerful patrons. Hereditary leadership persisted for two thousand years of recorded history, and obviously had grown up and become entrenched in previous millennia. While there are periodic instances of slaves, eunuchs and lower class leaders breaking in, the mainstream ongoing source of military leadership came from the upper classes who learnt basic military skills as part of their education, and gained preferment to command by inheritance or patronage. The system provided men who, in timocratic societies, both felt an obligation for service and took the opportunity for self aggrandisement and enrichment. It produced men trained to fight and lead from the front and, from the gifted, diligent and lucky, brilliant generals (2).

Such a system had its inherent weaknesses as well as strengths. Hereditary appointments and patronage ensured that the lazy, stupid, incompetent and unwilling had their share in running armies and pushing them to disasters but, with the deep suspicion of both the reliability and capability of the lower classes which pervaded oligarchic and even early democratic societies, the idea of training members from those classes to become leaders and take control of such a decisive political instrument was anathema. It was not until the simple direct clashes of men at arms began to be influenced decisively by the technology of artillery that this technology had to be taken seriously to the extent of extensive formal training in fortification and ordnance. In the United Kingdom this took the form of the Ordnance Department establishing the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich in 1741 to train professional officers for careers in the non-purchase Royal Engineers and Royal Regiment of Artillery (3). This expedient did not affect the cavalry and infantry where commissions were mostly subject to the purchase system or private raising of units, which perpetuated both the ruling class and amateur officer syndromes. However in 1802 a training establishment for the sons of deceased or indigent meritorious officers to gain non-purchase commissions was opened as the Royal Military College at Great Marlow, which eventually moved to Sandhurst in 1812, though this experiment lost its original purpose as fee-paying sons of the gentry progressively absorbed a majority of places (4).

Both Woolwich and Sandhurst had chequered beginnings, their graduates finding difficulty in acceptance in the Army due to the dubious academic standards and personal proclivities of the cadets (5), and to the ill regard for professionalism held by the mainstream of officers. But the beginnings of professional training had begun and were paralleled in France with engineer and artillery schools in 1742 and 1756, Austria 1748 and Prussia 1764; these early schools were replaced progressively in post-revolutionary France by Fontainebleu-St Cyr 1803 and in Prussia’s restructuring the Kreigsakademie in 1810. The United States established its military academy at West Point in 1802, Russia at St Petersberg in 1832 (6). With this competitive pressure there could be no turning back: training of an officer corps was beginning to produce an asset which would come to count as much as equipment technology and training of soldiers, and the various officer academies grew in competence and standing as industrialised warfare increased the nature, tempo and duration of conflicts, demanding staffs and trainers with an all-arms understanding and proficiency beyond the usual capacity of the amateur officer.

Australian Colonial Expedients

Australia’s colonial land forces were essentially non-professional, first as Volunteers, then progressively supplanted by partly paid volunteer Militia. Officers’ qualifications on appointment were usually listed as ‘gentleman’ with some minor exceptions: a man of substance who could ride and use firearms, and had the will to seek service, had the main characteristics required to lead infantry or mounted infantry. But the training of these leaders, and of their units, needed a more professional basis, as did the technical arms of the service. This was accommodated in part by the provision of permanent staff for overall command, administration and instruction, by the incorporation of officers and non commissioned officers with prior imperial service, by conducting schools of instruction in basic and technical skills, and by the use of the United Service Institutes to conduct coaching for examinations. Permanent instructors were attached to units during camps of continuous training, and also conducted the head-quarters courses for unit officers and instructors (7).

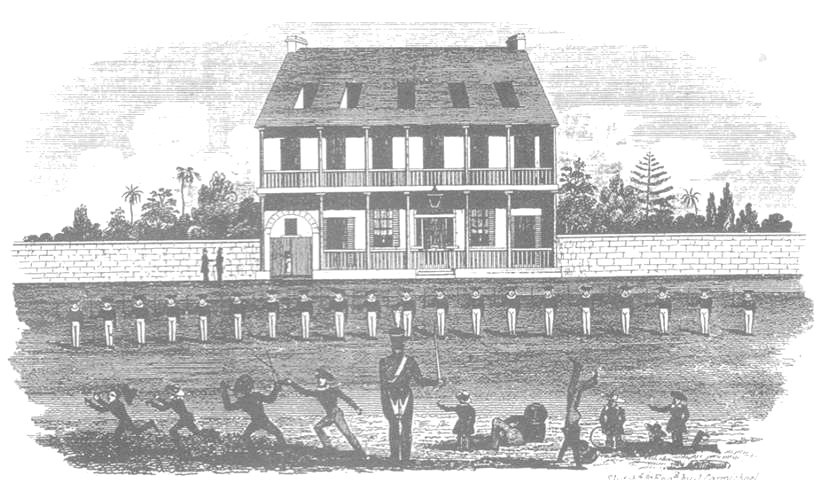

Military Training Normal Institution Hyde Park – Sydney 1938

The idea of training ‘cadets’ went back to Graeco-Roman times, and was well established within the public school systems of European countries. This early NSW school established ‘to train up the youths of the colony to be capable of acting as teachers of others’ carried into formal school cadet units, recognised as part of the Defence establishments of most Colonies from the 1860s.

The sergeant major of the British regiment on duty was made available to drill the students three days a week. Such training provided a basic entry to military drills and skills which stood many aspirants in good stead in their later officer training.

J. Carmichael from Maclehose Picture of Sydney

Expansion of the colonial defence forces, their progressive transition from Volunteer to Militia status, and increasing standards required by the technical arms, increased the pressure for a more professional approach. Victoria had introduced in 1863 a provision for its Volunteer Force officers to obtain a certificate of efficiency from a board of examiners at the Civil Service entry level examination plus military subjects for confirmation of their commission; New South Wales followed this, for military subjects only, in 1867 extending it in 1885 to include the Civil Service examination or a higher level within a year. This provisional system with a board of examiners was by then also in effect in Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and Tasmania, but Victoria and NSW with their larger defence forces were able to go further by establishing schools of instruction and requiring aspirant officers to obtain their certificates by attendance at formal courses at those schools (8).

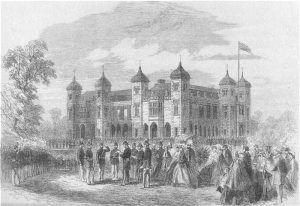

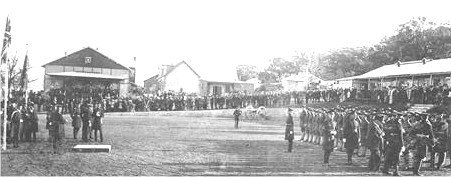

Presentation of commissions – Government House Perth December 1863

The presentations to officers of recently raised volunteer units were made before the paraded Enrolled Pensioner and Volunteer units.

Initially a case of patronage by the officers who raised units of the Volunteers, all the Colonies quickly adopted the system where basic education and military knowledge were a prerequisite for confirmation of probationary commissions.

The frequency of cancellation of commissions in the various Gazettes clearly attests to the insistence of the Commandants of the Colonial Forces on their aspirant officers attaining a measured adequate level of military competence.

Illustrated London News 19 March 1864

Lieutenant General Sir Andrew Clarke GCMC CB CIE 1824 – 1902

Commissioned into the Royal Engineers from the Royal Military Academy Woolwich, he served in Ireland, and at the urging of his father, Governor of Western Australia, served in Hobart as Royal Engineer. Subsequent service was in New Zealand, returning to Australia to become controller of the NSW Mounted Police, then Surveyor General in Victoria.

Further service followed in the Gold Coast, Governor of the Straits Settlements, Commandant of the Royal School of Military Engineering, then Inspector General of Fortifications, visiting Australia in 1885 and adding his support for a military college as well.

He retained an interest in Australia, becoming Agent-General for Victoria.

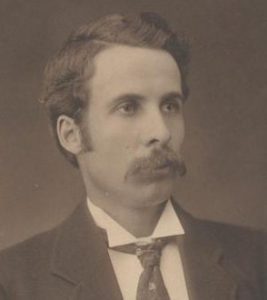

EDWARDS, Sir JAMES BEVAN (1834–1922), soldier, was born on 5 November 1834 in England, son of Samuel Price Edwards of Donegal. He was educated at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, and was commissioned in the Royal Engineers in December 1852. He served with distinction in the Crimea, in the Indian mutiny and with General Gordon’s ‘Ever-Victorious Army’ in China. In 1885 he commanded the Royal Engineers in the Suakin operations and then became commandant of the School of Military Engineering at Chatham. Promoted major-general in 1888, he went next year to Hong Kong as commander of British troops in China.

Following a recommendation of the Colonial Conference of 1887 Edwards was chosen by the British government to inspect the forces of the Australian colonies and to advise on their organization. He arrived at Brisbane in July 1889, inspected fortifications and troops in each colony and reported to the colonial governments in October. In recommendations published in the leading newspapers, he showed that the colonial forces lacked not only cohesion but the organization, training and equipment to fit them for defence of the continent. On questions common to the whole of Australia he proposed an organization which would enable the colonies to combine for mutual defence; he recommended uniform organization and armament, a common Defence Act, a military college to train officers and a uniform gauge for railways.

After leaving Australia Edwards carried out a similar mission in New Zealand and returned to Hong Kong. He resigned his command in 1890 and retired in 1893.

Permanent components were expanded and extended, a procession of imperial officers visited the colonies to report and advise on defences, and imperial officers were seconded to command the forces in each colony. Establishment of a military college in Canada in 1876 started thoughts of the Australian colonies having a similar institution. Raised in official circles by a royal commission in New South Wales in 1881, the idea became fairly universal and especially active with the Russian scare in 1885, where identification of the potential needs of expanding forces included a school for the training of permanent officers to provide an assured stream of instructors trained to uniform standards. This was raised by citizens of New South Wales in a petition calling for ‘a high class Military College’ and also by inspector general of fortifications Maj Gen Sir Andrew Clarke in 1885; by the Governor of Victoria to parliament to appropriate funds for a ‘College of Military Education’ in 1886; by visiting inspectors Maj Gen H. Schaw in 1887 calling for a college along the lines of the Canadian RMC Kingston, and Maj Gen J. Bevan Edwards in 1889; then by Maj Gen G.A. French as Commandant of the NSW Military Forces in 1897, and Maj Gen E.T.H. Hutton after Federation in 1903 as GOC Australian Commonwealth Military Forces (9).

Major General H. Schaw CB 1829-1902

Schaw was commissioned (non-purchase) from the Royal Military Academy Woolwich into the Royal Engineers, serving in England, Ceylon, Ireland and the Crimea.

Appointed Inspector General of Fortifications and Secretary of the Royal Defence Committee, he was invited to advise the Victorian and New South Wales and New Zealand governments on their port security in 1887. He extended beyond this brief, advising those governments on command and administration of their less-than-organised militia forces.

He retired in New Zealand and became active in the New Zealand Institute, also returning inspecting the NZ force during the Boer War.

Major General Sir G.A. French CMG 1841-1921

A graduate of both Sandhurst and Woolwich academies, he served in the Imperial forces in Canada, remaining after their 1871 withdrawal as Inspector of Warlike Stores, Commandant of the School of Gunnery and OC A Battery. He then became founding commissioner of the North West Mounted Police, bringing the lawless Canadian west under control.

As a colonel he became Commandant of the Queensland Defence Force in 1883 where he brought the force to a proper state of organisation and training, served in India from 1895, and returned as Commandant of the NSW Defence Force in 1899, continuing E.T.H. Hutton’s rebuilding.

He was promoted to major general and knighted after returning home in 1902.

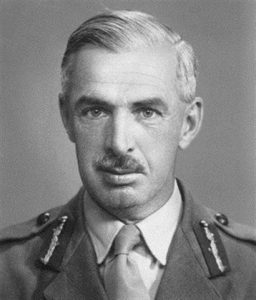

Lieutenant General Sir E.T.H. Hutton KCB KCMG 1848-1923

His British army service encompassed campaigns in South Africa and Egypt, and he was then appointed Commander of the New South Wales Defence Force 1892-96, during which period he not only revitalised the NSW forces but also promoted cooperation with the other colonies’ forces, and advocated a joint approach to Australian defence.

Hutton then moved to command the Canadian militia, which he set about transforming into a national army, followed by service as a mounted infantry commander in the Boer War.

Following Federation he was contracted to command the Australian forces 1902-06. During this period, although hampered by budgetary restraint, he was able to gain control of the drifting ex-colonial forces, and direct their structure and activities to progressing into a balanced national field force.

While there was little reason for opposition in principle to such proposals, there were real barriers. The problem lay in the nature of the forces – the part time Militia and the Volunteers were hard pressed to attend the limited annual camps and bivouacs of their normal commitment, much less a long course of instruction to qualify as an officer. The size of the colonial forces also precluded each having its own school, and while the technical schools of the Victorian and NSW Forces were used by the smaller colonial forces, setting up a single college as proposed had to overcome the institutionalised rivalry between the former two. Then the other factor was that of cost: during the 1890s and 1900s depression and drought ensured that there was little enough finance for even the meagre line units of the forces and the harbour defences, much less for an officers’ school. The concept was most applicable to permanent forces, and with just over 100 permanent officers all told in the Australian colonial forces, this hardly demanded an annual output from the smallest of colleges even were it to be a combined one and, as was the case with Canada’s Kingston, some graduates offered commissions in the British Army to justify the minimal output to make the college viable. The first meeting of the commandants of the colonial forces in 1890 decided that the time was not yet ripe for establishment of a military college proposed to be in Victoria and, even though they changed their tune in 1894, this had set a negative theme for the future. As alternative, the idea of setting up colleges within the universities of Melbourne and Sydney was canvassed, but the drought and depression 1890s were not ripe for military expansion (10). All the proposals languished.

Commonwealth Military Forces Solutions

Sir Edward Nicholas Coventry Braddon KCMG 1829-1904

Premier of Tasmania 1894-1899, he was a proponent of federation and elected as one of the Tasmanian representatives to the Constitutional Convention in 1897.

The draft Constitution gave the Federal Government power to levy customs duties, which were a mainstay of revenue for the colonies: Braddon insisted that the Commonwealth return at least three quarters of duties collected to the states. NSW threatened to withdraw from the Convention, so a compromise was reached where the Braddon Clause (or ‘Braddon Blot’) was operative for the first 10 years of federation.

This caused significant restrictions on federal budgets, including Army. Its lifting in 1910 enabled the funding of the Kitchener compulsory service expansion.

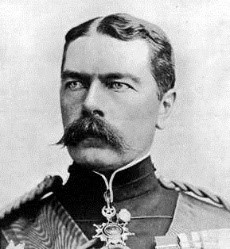

Field Marshal Earl Horatio Herbert Kitchener KG KP GCB OM GCSI GCMG GCMG GCIE ADC PC 1850-1916

Commissioned from the Royal Military Academy Woolwich into the Royal Engineers, he served as a surveyor in the Near East and in the failed relief of Khartoum. He became governor of the Red Sea Territories and commander of the Egyptian army, recapturing the Sudan after winning the battle of Omdurman in 1898. He was appointed commander of the Imperial forces in South Africa in 1900, bringing the Second Boer War to a successful conclusion, coincidentally signing the death warrants of Lts Morant and Handcock.

After a term as Commander in Chief in India and a failed attempt to become Viceroy, he toured the Empire, in the process preparing a report for the Australian government recommending a restructuring from the Hutton army to cope with the expansion arising from his recommended military conscription of all Australian youths.

In World War 1 he was Secretary of State for War, establishing the manpower and munitions necessary for the great prolonged and intense effort which he predicted. He died when a warship carrying him to a conference in Russia was sunk by a German mine.

It was not until the end of the first Commonwealth decade that sustained public and political support for defence arising from a deteriorating international situation, the improved availability of funds with the suspension of the Braddon Clause of the Constitution, and the training demands of the upcoming Universal Training army recommended by Lord Kitchener made the latter’s proposal, for a Royal Military College to sustain a Staff Corps of 350, not only a real proposition but also a necessity (11). But the function of that College was not as a training ground for command of the army: the citizen soldier would continue to command this citizen army. Suspicion of standing forces prevailed, handed down from the English regard of standing forces as tools of autocratic rulers and government; militias were of the underlying social structure and ‘constitutional’, the Army (that is standing army) was illegal without parliament’s consent (12). This inherited concept was reinforced in the new nation by the memory of the suppressive employment of imperial and colonial forces in the Australian colonies, carrying through in the Commonwealth Defence Act 1903 which was framed on the basis of the Army being the Citizen Military Forces. Permanent forces were forbidden, provision being made for ‘Administrative and Instructional Staffs, AASC, Medical and Ordnance Staffs, Garrison Artillery, Fortress Engineers and Submarine Miners’ (13), conceding no more than the need to man harbour defences continuously and provide some basic training and administrative services support to the Citizen Army.

Senator Sir George Foster Pearce KCVO PC 1870 – 1952

Starting life as a labourer then carpenter after leaving school at 11, he joined the union movement and entered politics through the Senate in 1901 as a free trader. Anti involvement in Britain’s wars, he became Minister for Defence in 1908 and promoted formation of an Australian Navy and compulsory military service.

After Kitchener’s recommendations he carried through a Naval Defence Act which included a naval college, and amendment to the Defence Act establishing a military college and compulsory training aimed at growing the army to 127,000 by 1920.

He remained Defence minister through World War 1 to 1921, promoting support of the war effort, including failed conscription for overseas service referendums in 1916 and 1917, then repatriation after the war, and the planning of the post-war citizen-army.

Duntroon’s output was therefore destined to train and administer the Army, not command it. Until this source came on stream instructional effort came from the Administrative and Instructional Staff which comprised permanent officers and non commissioned officers. Then, concomitant with the establishment of the military college, it was intended that permanent commissions would be available only in the Staff Corps which only graduates from Duntroon, including those entering that College from the ranks, could gain. Other instructors and administrative staff would be allotted to proscribed specialist corps or in the Australian Instructional Corps, whose members could be granted honorary rank, not permanent commissions. The advent of World War 1 before this system could get into operation clouded the issue, as the Duntroon output was allowed to join the Australian Imperial Force to meet the demands of wartime expansion, but a ceiling was placed on their rise to command ranks. The situation was made clear by Defence Minister G.F. Pearce in Parliament in 1917, in response to a complaint that the graduates were not being given the opportunity to progress to command positions, that (14):

It is the Citizen Force officer who will have to lead our Army in time of war. The Permanent Force officers are merely the instructors of our Citizen Force officers.

The first class, due to graduate in January 1915, was commissioned in August 1914 to join the Australian Imperial Force first contingent for the war in Europe.

This broke immediately with the intended use of its graduates as instructors for the Citizen Forces, but expedient needs have a sure way of bending the strongest of principles.

Subsequent graduates continued to fill places in later contingents to an expeditionary force which was hungry for reinforcement, but reverted to their planned function after the war, until World War II intervened, after which emergence of a regular army changed the function of permanent officers.

RMC Archives

The Kitchener Army expansion had put strains on the permanent officer situation in the preparation period before its effective inception in 1912. Apart from District administrative staff, there were planned to be 214 Permanent Area Officers to control the regional training of units raised under the scheme, together with an expanded instructional staff to conduct schools of instruction and assist in home and camp training. This liability grew as fresh echelons of compulsory trainees and the new units to hold them created further demands for training staff. The need for more full time duty officers for the home army was met largely from the Citizen Forces themselves, and as World War 1 wore on, from returned and home service officers unfit for operational service. Most of the Permanent staff remained overseas with the AIF, where their services were more required than at home training a Militia army which was not intended for the war, other than by providing volunteers for the AIF. In the immediate postwar surge in the Citizen Forces, returned temporary officers again filled the gap (15).

The vast demand for officers in the AIF created a parallel need. While the initial complement of the two expeditionary forces to New Guinea and the war in Europe was officered by volunteers from the Citizen Force, subsequent expansions and the ongoing drain of casualties had to be met from the ranks; the idea of training the bulk of officers in Australia for the front, rather than using the talent in the ranks which was so obviously revealed during operations, was both repugnant and impractical in outcome. As a consequence authority to submit recommendations for commissions direct to the minister was delegated to the GOC Australian Imperial Force, with officer training units in the bases in Egypt and the United Kingdom used to train and qualify aspirants: the ones in the latter were primarily the Officers’ Cadet Battalions at Oxford and Cambridge with artillery officers passing out of the Royal Artillery Cadet School at St Johns Wood (16). These courses took trained and experienced soldiers, preparing them for employment as junior leaders in a specific type of unit, this limited employment enabling the courses to be limited to three months, with any subsequent extension or change of duties being accommodated by an appropriate specialist course.

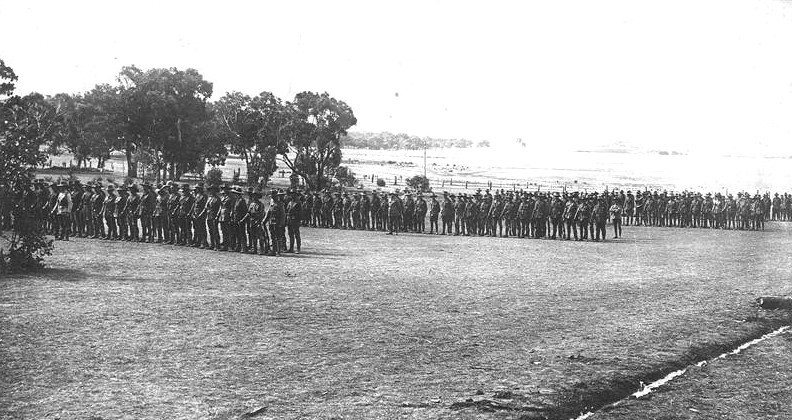

No 1 Officers’ Training School – Duntroon, April 1916

At first reinforcement officers for the AIF in the Middle East were trained in Australia and sent with reinforcement drafts. But as the overseas force became battle seasoned and produced its own officers from the practical talent in its ranks, the home source was sharply reduced, emphasis going to meeting the need for area officers for the Universal Training army of 100,000 still training in the Militia in Australia.

Officer courses for the AIF were held in the bases in Egypt and England, providing reinforcements for the seven divisions now on the Western Front and in Palestine.

RMC Archives

Disbandment of the AIF in 1921 and return to a peacetime army brought the Staff Corps situation to a head. An early reduction in establishments prevented any shortfall in the numbers required, indeed surplus RMC graduates left the army or transferred to the Commonwealth Public Service or the British and Indian Armies. It was not until the expansion of World War 2 that a large number of full time duty officers was required, and this spawned a repeat of the World War 1 officer training units and officer training wings of corps schools to meet a limited need with limited pre-commissioning training, followed as necessary by specialist courses.

Officer Cadet Training Unit Course on Tactical Training – Memphis, September 1941

This was one of a series of courses conducted in the AIF Schools of the Middle East Base, accelerated by losses in actions in the Western Desert, Greece and Syria, then the build up of 1st Australian Corps for employment in the upcoming battles against Rommel.

Departure of two divisions for the Pacific theatre in 1942 and the last division a year later ended an ongoing commitment which would have matched that of World War 1.

Parallel officer training was also conducted in Malaya for the 8th Division, but it too was short lived. Subsequent officer training then continued in the Australian base.

Australian War Memorial 020196

Officer training units were established by the AIF in the Middle East and Malaya, and by each corps and major formation in Australia (17). Big problems require big solutions, and in this vast expansion the continuing output of RMC was numerically irrelevant, even though its courses were shortened and increased in size; the output was absorbed into the AIF, where most wartime graduates received even less promotion than had their predecessors in World War 1. But the end of the war saw a mass exit of not only those commissioned in the AIF and CMF for war time service, but also a substantial percentage of RMC trained officers who re-entered civilian life along with their temporary service colleagues.

Officer Cadet Training Unit Graduation – Seymour, November 1944

With return of the expeditionary force from the Middle East, the Army was based on Australia. Commissioning of proven soldiers from within the ranks continued as the primary source of officers, and officer training schools were set up in Corps schools for units recuperating and retraining in Australia. It was, however, expedient to conduct other courses in remote areas, while RMC continued with shortened courses.

The output from No 14 Course of the Infantry Wing indicates the talent available: T.C. Derrick VC DCM and aborigine R.W. Saunders. Many of these officers attended RMC Wing courses to continue on the post-war expanded Regular Army.

Australian War Memorial 083166

The Regular Army Problem

The postwar Army created a unique need. Prohibition of permanent field units was removed from the Defence Act in 1947, as the aftermath of the war, the occupation of Japan and regional instability maintained a need for at least a modest standing force. In addition, in the Interim Army stage of wind down and demobilisation, and prior to reconstitution of the Citizen Military Forces in 1948, the command structure within Australia remained on the full time duty basis inherited from the wartime structure. Consequently a substantial increase in the permanent officer corps was created for command, administration and for manning the standing brigade group, as well as training of the recreated Citizen Forces. Availability of officers commissioned during the war who wished to serve on helped augment the small RMC output, and the requirement for graduation from RMC to qualify for a permanent commission was met by their attending six-week courses known as RMC Wings, held at the various corps schools and in Japan to spread the administrative and instructional load (18).

By the beginning of 1950 this still left a substantial shortfall of over 1,000 officers, and it was obvious that the asset of carryover wartime officers was a wasting one due to their ages. To add to the problem, the reintroduction of National Service in 1951, not just as conscription into CMF units but also with a preliminary three months of full time recruit training, created 10 national service training battalions and the need to provide staff to be rotated through them. With most wartime officers gone back to civilian life, and those with a continuing military inclination either already absorbed or with the force in Japan and Korea, even an expanded input to RMC would be slow in responding, and indeed the necessity for a four year course to train regimental officers for limited employment was not apparent: experience of officer production for limited employment from the two world wars suggested an expedient solution would bridge the gap (19). Just as the Universal Training scheme of 1911 created the expansionary impetus which made Duntroon feasible, so the National Service scheme forty years later helped create a similar one which led to the institution of the Officer Cadet School Portsea.

The model chosen was in existence for a different purpose. The Officer Cadet Schools at Mons and Eton Hall in the United Kingdom produced second lieutenants primarily to officer units of the British Army on the Rhine, its national contribution to NATO facing the Warsaw Pact forces in Germany. Those men were largely National Servicemen, required in a two year full time duty stint to do their officer training and one posting as platoon commanders, then a period in reserve, so the amount of training required could be curtailed and tailored to a specific function. It was not quite as easy with those required for the Australian National Service system: apart from the short recruit training phase, service was all in the Citizen Military Forces with no full time duty period, so sourcing officers for the full time national service training battalions from within the National Service trainees was not an option, although some confused thinking at Army Headquarters came to see National Servicemen as being the primary source of candidates for an Australian regular officer cadet school (20).

Developing a Solution

Acceptance by the Military Board of the urgent need for generating additional officer production to supplement the Australian Staff Corps resulted in the issue of a Military Board Instruction in September 1950 calling for applications for Australian Regular Army commissions from serving officers of the Interim Army and CMF, Reserve of Officers and warrant officers and sergeants. It was accepted that some direct entry commissions would be given to technically qualified civilian applicants with the necessary educational and professional qualifications for RAE, RA Sigs RAAMC, RAAOC, RAEME, RAAEC and ACC, all of whom were to undergo the equivalent of the successful short RMC Wing courses. But the Directorate of Military Training in Army Headquarters anticipated several hundred applicants from serving members and some 60 of these had already been accepted for appointment to commissioned rank subject to qualification at a proscribed course. It was this course which now became the centre of urgent consideration, with the Directorate of Military Training proposing a two pronged solution: a four-week RMC wing type course for those with previous military experience, and a ten month course for those without (21). Although there was still to be considerable debate and counter-marching, with the categories of service-no service altered to an age division, this quick initial reaction became entrenched as a durable solution to the problem: the short course was used to qualify the immediate batch of serving candidates, but survived as the Officer Qualifying Course for NCOs over 23 years of age; the OCS Course was established for servicemen and civilians under that age.

The long course was to be a two phase one, the first an Officer Candidate Course of five months ‘to achieve a high standard in military subjects common to all arms’ to be followed by an Officer Candidate (Arm or Service) Course of similar duration ‘to fit the member for duty as a commissioned officer in his Arm or Service’. The former was to be held at the School of Infantry at Seymour, the latter at the appropriate corps schools, with an expectation of no commencement before 1951; but while Army Headquarters fiddled on establishment of the Officer Cadet School, it became acutely necessary to deal with those already selected for commissioning from applicants from the Regular and Citizen Forces. Two courses, conducted for administrative convenience at the School of Artillery in November 1950 and the Staff College Queenscliff January 1951, met the immediate need with temporary staffs, but this ‘ad hoc arrangement’ to meet the now embarrassing outstanding liability of the already approved applicants from mid-year merely underlined the requirement for a durable organisation with proper facilities to carry what was obviously an ongoing requirement (22).

While this quick fix had solved the most pressing problem, the ongoing one was unresolved. Indeed the disruption to the programmes of the School of Artillery and Staff College had demonstrated the impracticability of superimposing an ongoing annual liability estimated at 300 or more candidates on one existing school, while the lack of continuity and administrative implications of rotating the All Arms courses between schools would simply compound the problem. In September 1950 DMT proposed raising an Officers’ Training Unit with a course capacity of up to 70 students commencing on 1 February 1951, located at Lonsdale Bight near Queenscliff where it was believed that recent improvements to the camp accommodation would serve for up to 150 at a time. At this stage DMT thinking was dominated by the requirement for testing candidates applying under the Military Board Instruction, but as a supplementary justification for a separate school it was suggested that it could be retained subsequently to give special training to CMF members who were potential officer material, particularly ex-National Servicemen, and as a base for expansion on the outbreak of war. These fairly woolly ideas merely represented the habit of the less gifted to substitute quantity of reasons for reasoned argument (23), but nevertheless they foreshadowed transition to a broader concept which catalysed a progression to the final solution.

Lieutenant General Sir Sydney Fairbairn Rowell KBE CB 1894-1975

He graduated from the first class of the Royal Military College Duntroon at the beginning of World War 1, being medically evacuated from Gallipoli and becoming an instructor at the Officers’ Training School collocated at Duntroon. In the postwar army, he filled a variety of staff appointments and joined the 2nd AIF after the outbreak of World War 2.

During that war, he served in the Middle East on HQ 6th Division, was Brigadier General Staff on 1st Australian Corps, and returned to Australia as DCGS, then GOC 1st Australian Corps in New Guinea. Here he had a falling out with Commander in Chief Blamey, who had been sent to New Guinea by over-agitated Prime Minister Curtin and General Macarthur. The presence of Blamey and Rowell trying to exercise command through the same headquarters was impossible, unless Rowell consented to be Blamey’s chief of staff, which he refused. He was reverted in rank and banished to inconsequential postings in the Middle East and UK.

In the postwar era, with Blamey gone, it was inevitable that a professional soldier of his experience should rise towards the top: he became VCGS then Chief of the General Staff in 1950.

Faced with the problems of an officer shortage in the postwar era, he saw the need to establish a shorter course than the restored four-year one at Duntroon, and became the godfather of the Officer Cadet School Portsea.

That initial woolliness had to a large extent been shaken out by December when Chief of the General Staff Lt Gen S.F. Rowell espoused ‘opening up an additional and lasting channel’ for commissioning in the Australian Regular Army through an Officer Candidate School on the lines of the United Kingdom system for training officers within their National Service scheme, nominating an OCS which would take candidates from junior CMF officers, ARA other ranks, RMC applicants with officer potential but not able to meet the academic requirements, and National Servicemen selected after their continuous training period. In a joint submission with the Adjutant General to the Military Board a month later RMC was defined as the source of future senior staff officers, technical staff officers and, more cautiously from Staff Corps officers still emerging from the shadow of the citizen-soldier command oligarchy of the previous half century, ‘probably a high proportion of Commanders’. They recognised RMC’s inability to either meet the current large deficiency of over 900, or the high maintenance drain of replacing future waste out of short service officers and those inducted through the RMC wings. They did not believe that it was desirable or economical to increase RMC’s output as the increases in the Regular Army requirement were mainly in National Service and Field Force units: the compelling need was for junior regimental officers, and they noted that Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom supplemented their principal military college output with a similar system (24).

A further impetus to come from these Military Board considerations was that of the replacement of male officers by female ones where this was practicable. To find and qualify such officers for Australian Regular Army service required a similar solution to that being canvassed for male regimental officers, but it was far too early in the development of military attitudes to female soldiers for any suggestion of their attending the same institution, from both sides of the gender barrier. The male hierarchy saw women as filling routine administrative tasks in the base context with no suggestion of fleshing out the field force, so the major operational content of a regimental officer course was inappropriate and indeed unachievable for female officers; and in the female hierarchy the carryover of the World War 2 Australian Womens Army Service attitudes of separateness and segregation into the upcoming Womens Royal Australian Army Corps ensured that there was no ambition to join the male mainstream training. After initial officer qualification courses at Mears House Watsonia paralleling those for males at the School of Artillery and Staff College, the WRAAC Officer Cadet School was set up at Mildura in June 1952, moved to Georges Heights Sydney in 1957 where it remained, until the inevitable if delayed decision to dispense with the WRAAC and simply have male and female soldiers resulted in that School’s absorption into OCS in its final year of operation in 1985, before it in turn was absorbed into Duntroon (25).

Sir Frank Roy Sinclair CBE 1892-1965

A lifelong Defence bureaucrat, he began as a junior clerk in the Defence Department in 1910 and became Assistant Secretary of the Military Board 1914. Appointed lieutenant in the Australian Army Pay Corps in 1917, he served as paymaster 4th Division in France.

Postwar he progressed to Accountant Army 1929, Secretary of the Defence Committee 1937, Assistant Secretary Department of Defence 1938, and served on the secretariat of the War Cabinet and War Council with Defence Minister Frederick Shedden from 1940.

Appointed Secretary Department of Army in 1941, he was an activist on army administrative matters, so earning staunch criticism from C in C Blamey, but was recognised as a competent public servant and retained his position under successive ministries until 1955.

Preparation of the Military Board submission not only firmed up the idea of tapping the source of junior CMF officers but also brought in those CMF members qualified for first appointment to commissioned rank; it included ARA other ranks, appropriate RMC applicants plus RMC cadets unable to handle the tertiary level academic studies but suitable for regimental duties; and for the first time suitable other young civilians. The standards of character and potential leadership were equated to those of RMC entrants, with a lower initial education standard; minimum age was set at 18 years with an upper limit of 22 to allow a reasonable career period; and on successful completion of the course graduation would be as a second lieutenant, with promotion to lieutenant after four years and completion of leaving standard education. The course would be 22 weeks covering all arms skills plus staff duties, military law, organisation, administration, current affairs, military history, intelligence, tactics and methods of instruction, approximating to the content of the RMC Special Entry classes of 1939; after graduation a special to arm course of 20 weeks was to be completed at the appropriate corps school (26).

Sir Arthur Harold Tange AC CBE 1914-2001

Joining the public service as a research assistant in Department of External Affairs in 1954, he rose rapidly to become Secretary of the Department, then in 1965 moved to High Commissioner to India.

Returning in 1970 as Secretary for Defence, he set on a path of amalgamating the separate Departments of Army, Navy and Air Force into it, creating an immense bureaucracy not answerable to the Defence Force command system. This amalgamation was in place in 1975 when he is on record as stating that he created the super-department ‘to facilitate efficient administration of Defence’. In this there was no mention of the fact that the function of Defence is Defence, not administration.

While there was a compelling need to push the divergent Services onto a common path of joint operation, his chosen path of a vastly overblown civil and military bureaucracy, cemented and expanded by his successors – civilian and military – consumes a large part of Defence funding, and also presides over spectacular failures in major equipment projects.

Secretary for Army F.R. Sinclair, who had recently returned from a visit of army establishments overseas in which he had discussed officer training, warned against short courses for Regular officers which would tend to adversely affect their standing as professionals, however in the days of Service Boards the Secretary was merely one of the members, having to convince his Service colleagues of his arguments, rather than the later hundred-odd independent senior Defence bureaucrats who were able to obstruct the so-called Service command structure following the Tange reorganisation. The Military Board was not convinced, having identified a clear and pressing need for rapid production of junior officers to allow the expanding Army to function (27). Shortened courses had solved the need in the serious business of two world wars, and these were a usual component in other militarily sophisticated countries as a matter of routine to solve short term deficiencies and limited needs. As well, what was being proposed here was a considerably enhanced period of tuition without relaxation of entry standards.

Sir Josiah Francis MHR 1890-1964

Jos Francis served in the AIF with 15th Battalion, was wounded and rejoined his unit. After the war he involved himself in ex-service welfare as president of Ipswich Sub-branch and Moreton District RSL.

Elected to the House of Representatives in 1922, he remained in parliament until 1955, always a champion of ex-service welfare, and holding minor ministerial portfolios.

Francis was Minister for Army in the first Menzies Government 1949-55. He managed to secure adequate budgets for Army (and Navy when its Minister) and was respected by the service chiefs, even though regarded politically as a plodder. His support for the establishment of OCS at Portsea was crucial.

The proposal was agreed and approved by Minister for the Army Jos Francis, with the first course to open with 30 students. While an early start was both envisaged and considered essential, with a beginning now proposed for July 1951, there were hurdles to overcome. A growing obsession with having a high proportion of National Servicemen as entrants, fed by analogy with the British experience but not borne out by the reality of the first intake to OCS, spawned proposals to increase the course to 28 weeks in two 14 week sessions to coordinate with two 14 week National Service full time training periods, with 20 cadets per course and involving overlapping courses to maintain the targetted 60 per year throughput. Better sense prevailed and it was decided to employ National Service entrants in the Regular Army while awaiting commencement of an OCS course. The tentative July start was held in abeyance on the basis of delayed Treasury approval militating against such a date, plus concerns beginning to arise on the intended venue, though the magnitude of this latter was not yet recognised as the problem which it turned out to be; the opening date was subsequently deferred to January 1952 to ensure that all arrangements could be put in place adequately. Indeed the authorising instruction was not promulgated to Command Headquarters for implementation until October 1951, and even then the location was uncertain (28).

The immediate need was established, the solution was agreed, but the means were still elusive. However the strength of any effective army is that it has the means and the men to make things happen, and now Headquarters Southern Command had been given the task of raising the School to commence activity by 7 January 1952. The great strength of the Army during its period of operating in the geographic command mode was unity of command and hence ability to harness all the broad range of resources at its disposal in any particular location: one way or another it would happen, as long as a suitable site could be made available.

References

- As examples Aristotle Constitution of Athens 3.2, 55.3; Polybius VI.12; Lewis N. & Reinhold M. Roman Civilisation vol II, p121-8.

- British generals were given large cash ‘success fees’ after World War 1, and there was an unfulfilled expectation of the same after World War 2 (see Bryant A. Triumph in the West); Tuner E.S. Gallant Gentlemen, p15-22; Bond B. The Victorian Army and the Staff College 1854-1914, p7-9.

- Smyth J. Sandhurst, p27f; Holloway D. ‘Formation of the Australian Military Elite’, p9-11.

- Smyth, p47f, 51, 54, 56-7.

- Smyth, p53, 65-7, 76.

- Bond Victorian Army, p9-19.

- eg Votes and Proceedings Queensland Legislative Assembly vi 1885 Regulations, p709; Votes and Proceedings New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1890, 1891 vol 2 Commandants’ Reports, p212, 266; 1894-5 vol 5 Hutton Report, p402; Papers Presented to the Parliament of Victoria 1884 vol 2 No 32.

- Victoria Government Gazette 1863 No 129, p2875; PP Victoria 1885 vol 4 No 83 Report of the Council of Defence, p3; 1889 vol 3 No 36 Regulations s.V.7,8; V&P NSW LA 1867-68 vol 2 Regulations, p300; 1885 v2 Regulations, p629; V &P QLA 1885 vol 1 Regulations, p709-10; Parliamentary Proceedings South Australia1887 vol 2 No 32 Regulations, p2; Votes and Proceedings Western Australia Legislative Council 1882 No 9 Report Upon the Volunteer Force, No 32 Report; 1883 No 8 Report; 1884 Report; Hobart Gazette 1886 Regulations sV.39-41.

- V&P NSW LA 1881 vol 1 Report of Military Defences Inquiry Commission, p25; 1885 vol 1, p39, 67; Votes and Proceedings Victoria Legislative Assembly 1886 vol 1, p715; V&P NSW LA 1887 vol 2 Report by Major General Schaw on the Defence of New South Wales, p47; 1897 vol7 French Report, p18; V&P QLA 1889 vol 1 Report by Major General Bevan Edwards, p1354; Papers Presented to the Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia 1903 vol 2 Hutton Report, p20. For further reading on the progression of ideas for an Australian military college see Coulthard-Clark C.D. Duntroon Introduction.

- Queensland Archives Colonial Secretary’s Office (IN) 1767191 of 11 May 1891; V&P NSW LA 1895 vol 5 Report on the Military Conference 24-26 October 1894; CPP 1903 vol 2 Naval and Military Forces of the commonwealth, p4.

- CPP 1910 vol 2, Memorandum of the Viscount Lord Kitchener, p95; Commonwealth of Australia Defence Act 1903.

- Barnett C. Britain and Her Army 1509-1970, p110, 115, 123, 173.

- Defence Act 1903, 831 (2); subsequent amendments extended this to include the Australian Staff Corps, Survey and all Artillery, but the restriction of cavalry and infantry remained – so much so that the Darwin Mobile Force in 1938 was raised and dressed as artillery, even though most of the members were infantry.

- Parliamentary Debates v 82, p1364.

- CPP 1910 vol 2 Kitchener Memorandum, p93; Military Orders 468, 606/1915; Scott E. Official History of Australia in the War

- Bean C.E.W. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18 vol 1, p412; vIII, p53; Australian Imperial Force Orders 1/1915 Order in Council 730 Of 1914; AIF Orders 156/1917, 164/1917.

- Long G. To Benghazi, p5; AIF Orders (Middle East) 1206 of 1 August 1942 Graduation of AIF Students from ME OCTU; Coulthard-Clark Duntroon, p86, 114.

- Military Board Instruction 50/1948 Appointment of Additional Officers to the Australian Army.

- Australian Archives MP927 A259/18/29 of 25 January 1951.

- MP927 A259/18/29 of 27 September 1950, 7 December 1950.

- Military Board Instruction 152/1950; AA MP927 A259/18/29 of (undated) March 1950.

- AA MP927 A259/18129 of 28 June 1950 and 27 September 1950.

- AA MP927 A259/18/29 of 27 September 1950.

- AA MP927 (UK) AC/240-243 of 1951; A259/18/29 CGS 290/1950

of 7 December 1950 and Military Board Agendum of 25 January 1951. - Ollif L. Colonel Best and Her Soldiers, p237-8; AA A3688 79/R2/42 of 19 February 1951.

- AA MP927 A259/18/29 of 30 May 1951; AA 82453 79/R2/42 Board Minute on Military Board Agendum No 10/1951; AA MP897/1 27/32/9 of 8 October 1951.

- AA A3688 72/R2/42 of 19 October 1950; AA 82453 79/R2/42 Board Minute on Military Board Agendum No 10/1951 para 5.

- AA A3688 79/R2/42 Military Board Minute on Agendum No 10/1951 of 19 February 1951; MP897/1 27/32/9 of 17 October 1951; MP927 A259/18/29 of 17 April 1951, 30 May 1951.