4

Early Settlement

Captain Philip Gidley King 1758-1808

His naval career had included early service in the American War of Independence, and later under Arthur Philip, who selected him as an officer for the Sirius. On arrival in NSW he was sent to Norfolk Island to establish a station and examine the prospects of ships masts and flax as a source of naval stores.

After being sent home by Philip to explain the difficulties experienced in the new colony, he returned to Norfolk Island and faced difficulties in keeping order amongst mutinous soldiers, clashing with Acting Governor Grose. However he made the station self-sufficient, with excess for export to Sydney. Ill health forced his return to England, and when he returned in 1800 it was to replace Governor Hunter.

King attempted to control the rum trade and controlled prices by setting profit margins on imports, using the Commissariat as the agent. He encouraged government and private production of foodstuffs, and allowed ex-convicts to progress in the community. The part of the population ‘on the stores’ was halved. However his successes were minimised by his Rum Corps opponents who stood to lose from his changes, and he was replaced by Bligh in 1806.

Admiral Sir Arthur Phillip 1738-1814

Captain Phillip was appointed Governor of New South Wales on the basis of his experience controlling a convict-manned military and trading colony in Brazil when on secondment to the Portuguese navy during the Spanish-Portuguese war.

He established the military colony using convict labour at Port Jackson in 1788, returning home ill in 1792, and leaving Major Francis Grose as acting Governor.

He was promoted to Admiral after his return to England.

Captain Cristovao de Mendonca 14xx-1532

Son of the Alcade of Mourao, Mendonca entered the Portuguese navy and left Lisbon in command of a ship in 1519 for Goa. He was instructed in 1521 to take three caravels from Malacca to search for Marco Polo’s fabled Isles of Gold in the New Guinea area, and also intercept a Spanish fleet under command of the Portuguese mercenary Magellan which was coming around Cape Horn headed for the Philippines.

Mendonca expected that the imagined coastline of the southern continent sloped down towards Cape Horn, and by coasting down it he would run into Magellan. The latter however turned right up to the Equator and then turned across to the Philippines, leaving Mendonca following the Australian coastline which turned south.

While there is no direct evidence of the extent of this voyage, it is recorded in the maps of the mapmakers of Dieppe in the middle of the 1500s: one by Jean Rotz (a Scot whose real name was John Rose) given to Henry VIII by Anne of Cleeves as a wedding present, shows a better outline of Australia than it does of fairly well known South America. Other circumstantial evidence includes the Mahogany Ship near Warnambool (the east coast limit of the Dieppe Maps), the Geelong Keys and the ruins at Bittangabee Bay near Eden, plus some artefacts in New Zealand.

Port Phillip was surveyed by Portuguese captain Mendonca’s expedition down the east coast of Australia in 1522-23, the bay’s outline clearly identifiable in the Dieppe maps of a couple of decades later. Lieutenant Matthew Flinders and George Bass in the Norfolk passed through the strait between Van Diemen’s Land and the mainland in 1798, and two years later Lieutenant James Grant in the Lady Nelson passing through Bass’s Straits called the entrance to the bay Governor King’s Bay. In February 1802 Governor King sent Lieutenant John Murray in the same vessel to explore the inner bay which the latter called Port King, also naming Arthur’s Seat, and calling Point Nepean after the then Secretary for the Admiralty. Two months later Flinders in Investigator on passage from England to Sydney entered the bay, which King had renamed Port Phillip in deference to his predecessor and patron, naming Indented Head and Station Peak. Reports from these visits stimulated King to send Surveyor General of New South Wales Charles Grimes to survey the Bay early the following year and from this survey Flinders completed his provisional chart of it; but the French Baudin expedition in 1802, in its customary fashion sailing well out to sea naming existing and non-existing headlands and bays, had managed to avoid noticing the entrance to Port Phillip (1).

Prime motivating factors of this British interest were apprehension that the French would establish a settlement in Bass’s Straits, the increasing importance of the sealing and whaling industries, and the need to provide further outlets for convicts. The Botany Bay penal colony had been established in 1788 as one of a series of strategic bases from Sierra Leone through to the Indian Ocean to the Pacific to protect the East Indies trade, particularly from French incursions. La Perouse’s arrival at Port Jackson four days after the First Fleet entered Botany Bay lent some substance to a fear of French designs on the continent and, with the possibility of renewed war after the 1802 peace, a hostile base in the Strait was a clear danger. A successful sealing industry had been established in the Strait from 1798 so a British base in the area was desirable, while the anticipated flow of convicts sent for permanent exile would obviously strain the absorption capacity of the settlements at Sydney, Parramatta and the Hawkesbury. The time was right for a new settlement in the south of the continent (2).

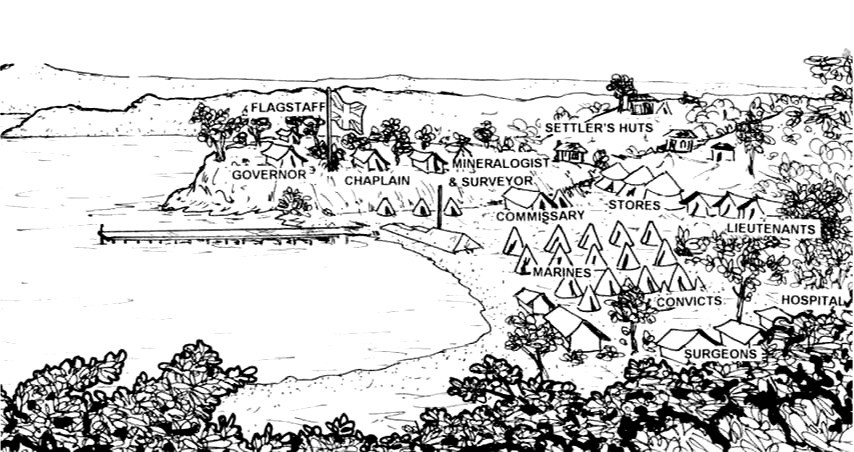

Lieutenant-Colonel David Collins, a first fleeter and Attorney General of the Colony of New South Wales who returned to England in 1796, was commissioned as Lieutenant Governor commanding a party of 466 comprising 11 civil staff, 50 marines, 19 settlers with 21 of their family members, and 299 convicts with 29 families including an eleven year old boy John Fawkner, to establish an outpost in the bay. HMS Calcutta with the official party arrived on 9 October 1803, linking up with the transport The Ocean which had arrived earlier after becoming separated by a storm; camp was set up between Arthur’s Seat and Point Nepean on the foreshores between The Sisters at Sorrento, which was named Sullivan Bay after the Under Secretary for War and the Colonies. Collins found the sandy soil and poor water supply unsatisfactory for a settlement and, with Lieutenant James Tuckey reporting similarly on the rest of the Bay, began agitating for removal of the settlement to Van Diemen’s Land. King agreed and the area was finally abandoned in May 1804 to its native inhabitants (3).

A settlement in Port Phillip District was a natural extension of late 18th and early 19th century British policy of protecting trade and resources by progressive establishment of military colonies from Sierra Leone through the Indian Ocean and Pacific to Vancouver.

Whaling and sealing in the Southern Ocean and Pacific were particularly important as at this time London burned more oil in its street lamps than the rest of Europe combined, and seal fur was in great demand. Consequently protection of this trade from French incursion was of prime significance, and convicts provided a convenient workforce which would also rid the home country of its more troublesome citizens.

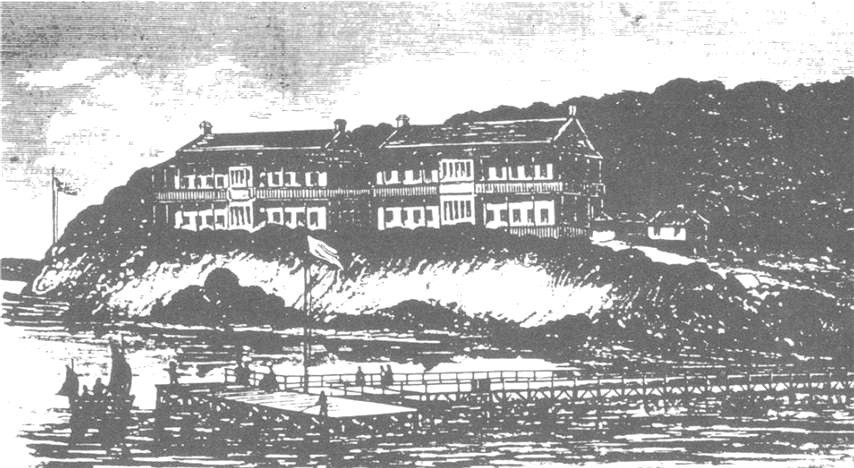

L.C. Cox after a drawing by G.P.R. Harris. in the British Museum London

No traces of the original inhabitants of Australia have so far been discovered in the Mornington Peninsula. However by the time of the Collins and later European settlements, of the Australoid people who occupied the continent up to forty thousand years ago, the western branch of the Bunurong tribe used the land from the Peninsula through to Carrum in the north and the Dandenong and western Strzelecki Ranges in the east. Collins and his settlers had little contact with the native inhabitants, but Tuckey in his exploration of the bay met several small parties who were friendly, already with experience of Europeans, having both a knowledge and fear of firearms, and one showing smallpox scars, a probable legacy of contact with the sealers of Bass’s Straits in the previous five years. The fear of firearms is likely to have come from an incident in February 1802 at Sorrento when a shore party from the Lady Nelson had a skirmish with a small party of aborigines resulting in two of them being wounded. Tuckey’s expedition subsequently had a major confrontation on the western side of the bay with a large group of one to two hundred which, after some initial skirmishing, made a concerted attack, forcing his party to open fire with the resultant death of a warrior. However the only surviving runaway convict from the Collins settlement William Buckley was accepted by the natives, moving through the Bunurong, the Woiworung in the Yarra Valley and then, to the west of the Bay, the Kurung and Wathaurung, becoming one of them until he eventually turned himself in to John Fawkner’s depot at Indented Head on the western Bay after its establishment in 1835 (4).

Bunurong at Sorrento 1803

The only known representation of this tribe which died out within 70 years, it is sketched in the comer of the chart Lt James Tuckey made of the bay. It shows the weapons and the possum skin coats which were appropriate to the weather of Victoria.

The aborigines of central southern Victoria have been described as the Kulin people by G. Presland in The Land of the Kulin; said to comprise the Bunurong, Woiworung, Taungurong and Wathaurung, however as he acknowledges that Kulin simply means human beings, and as these tribes were known to be often in conflict, this connection is perhaps tenuous.

Little memento of the Bunurong tribe itself remains other than the middens and artefacts which have been found on the Mornington Peninsula.

from ‘Port Phillip in Bass’s Strait’

a copy of the original Tuckey chart in the British Museum by F. Dossete 1804

William Thomas was appointed Assistant Protector of Aboriginals in 1839 for the area east of Port Phillip through to Gippsland with the duties ‘to move with the Aboriginals, learning their languages and customs, their numbers and tribal areas and safeguarding them from encroachments on their property and from acts of cruelty, of oppression or injustice’. These problems had already been visited on the Bunurong before his arrival, their songs recording that the Gippsland tribes had killed half of them a decade after Collins departed, with another 20 lost in further inter-tribal attacks in about 1831 and 1836. Additional depredations of Bass Strait sealers kidnapping women and the evidence of smallpox in the population, possibly introduced by the sealers from about 1798 had so further reduced their numbers that Thomas’ November 1839 census showed only 83 remaining, indicating a likely population at the time of the Collins settlement of about 300. Even these few remaining tribesmen were plagued by venereal disease and dysentery, and although they raided the Gippsland tribes for women, the effects of disease, alcoholism, murder, executions, shooting by the white authorities and death in gaol had by 1850 reduced their number to 28 with no children. None was seen in the southern part of the Mornington Peninsula after 1856, the remaining survivors living a precarious and degraded existence on a reserve at Mordialloc, with the last of the full blood tribesmen dying in 1877 (5).

These inhabitants were originally semi-nomadic, living from fishing, hunting and gathering, making periodic seasonal circuits to exploit the resources of their tribal area. The western branch of the tribe moved from south of the Yarra along the bayside to Point Nepean then along the sea coast to Western Port, completing the circuit back through Dandenong. Some references indicate a group in the southern part of the Peninsula known as Tal Tal, which was probably the clan name of a group which remained in the area after settlers moved in and began to provide a source of employment and food. A letter by pastoralist George McCrae in 1846 records such a large group on Arthur’s Seat property that it must have included a temporary augmentation by other visiting tribes, presumably the Kurung from across the bay with whom intermarriage was normal. McCrae described them as a mild, inoffensive fishing tribe, both useful and trustworthy; Robert Jamieson of Cape Schanck found them quiet, inoffensive and willing. But the adverse influence of the colonists made itself felt: subsequent records show them as spoilt by the settlers, decreasing to small groups cadging food and unwilling to work for it (6). Never populous, and subject to depredations from other tribes, disease and the colonists, their early demise was inevitable.

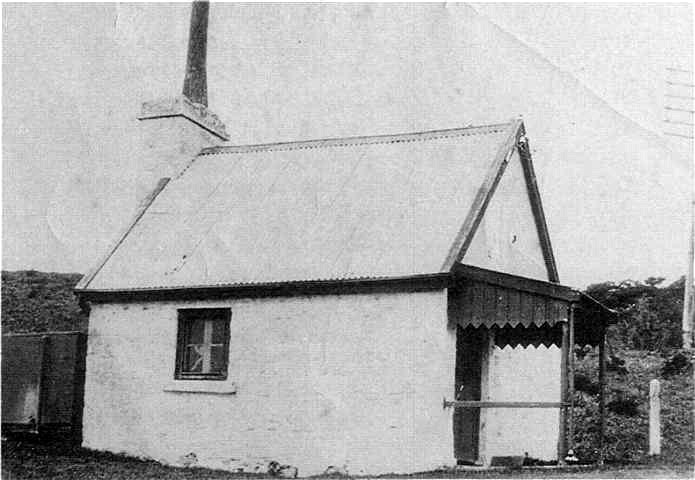

Thought to be built on the site of the oldest building in the area which was an underground dairy and wattle and daub hut, by 1854 the above ground structure was a limestone cottage, used successively as the storekeeper’s house (1854), paint store (1875), dairy (late 1800s), then as an office and store. The cellar was forgotten until 1941 when a Quarantine foreman rediscovered it and it was used as an air raid shelter.

The building was latterly the Regimental Sergeant Major’s office.

Nepean Historical Society

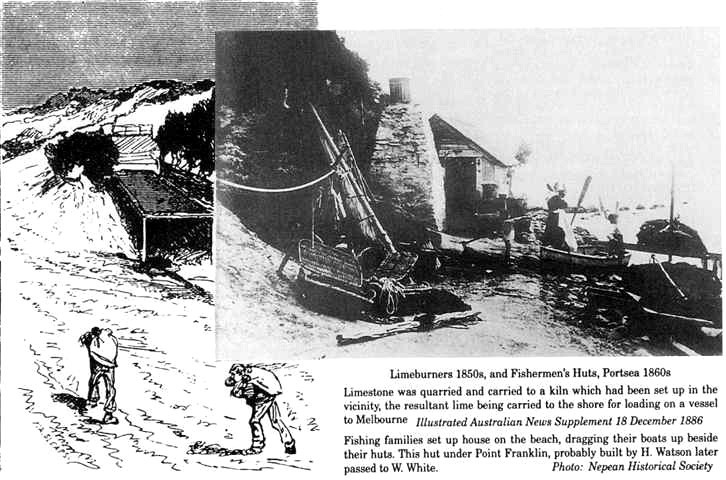

After Collins’ aborted attempt the next recorded white settlement on the Peninsula was in June 1837 when Edward Hobson established a pastoral run at Kangerong, while Robert Campbell set up at Cape Schanck, selling out in 1839 to Robert Jamieson who then onsold it to others. Further settlers Willoughby, Thompson, Meyrick, Desailly and Smith were in the area as pastoralists by the end of that year (7). Edward Hobson took a second run at Tootgarook in 1838, extending to Point Nepean. Subsequent land acts provided for closer settlement in the areas claimed by the squatters so in 1842 James Ford with his wife and several young children selected an area astride the present Portsea Back Beach road from the present town to the sea coast, naming it after a dockside suburb of his native Portsmouth. When he arrived the area was open grassland with casuarina and melaleuca trees, on which he raised cattle and horses which he sold to newer selectors anxious to stock their runs. Three years later Dennis Sullivan arrived with his family at Portsea, occupying the area west of Ford’s to Point Nepean, farming, grazing and lime-burning. The peninsula was well supplied with limestone formations so quarrying and burning of lime to supply Melbourne’s need for cement became a significant industry from the late 1830s. Kilns were set up by Dennis Sullivan and William Cannon in what later became the quarantine reserve, while to the east a further series through to Tootgarook was established by the Sullivans, Fords, Skelton and many others, employing ex-convicts, Aborigines and Chinese. Sullivan is reputed to have made a foray to the goldfields in 1851, returning within the year to the more secure living on his Portsea property (8).

Limestone was quarried and carried to a kiln which had been set up in the vicinity, the resultant lime being carried to the shore for loading on a vessel to Melbourne Illustrated Australian News Supplement 18 December 1886 Fishing families set up house on the beach, dragging their boats up beside their huts.

This hut under Point Franklin, probably built by H. Watson later passed to W. White.

Nepean Historical Society

The gold rush which temporarily seduced Sullivan also brought an immigrant rush, and with it the threat of disease epidemics. At first the occasional immigrant ships were inspected at Red Bluff (Point Ormond) initiated in 1840 by arrival of the Glen Huntly with typhus aboard, isolation and treatment being effected ashore in tented accommodation. As other vessels arrived with infectious cases and the pace of immigration escalated after the discovery of gold in 1851, the newly formed Victorian Legislative Council initiated a search for a permanent sanatory station away from the expanding urban area, confirming the site at Portsea in early 1852 with an allocation of £25,000 for construction. The Sullivan and Cannon families were given a month’s notice of resumption of their land on 28 October to enable construction to begin but this was preempted on 6 November by arrival of the Ticonderoga from Liverpool with eight hundred passengers on board, nearly a hundred having already died of typhus A vessel which had overtaken the ship in passage had brought the news ahead to Melbourne so the schooner Empire was dispatched to The Heads with fresh provisions, followed by the Lysander as a hospital ship with stores for three months. Ticonderoga was anchored in the bay now bearing its name, the worst cases transferred to Lysander and the remainder of the passengers disembarked. The Sullivans and Cannons were moved out and resettled forthwith so that their buildings could be used to house the disembarked passengers, with the overflow accommodated in tents made from ships’ spars and sails.

Sullivan’s cottage represented, together with Cannon’s, the original houses of the Nepean Peninsula. The building was used for the Ticonderoga emergency and later quarantine, being demolished about 1910. Dr J.B. Browning on the steps was Resident Medical Officer 1885-1897.

Nepean Historical Society

This incident concentrated the Legislative Council’s attention on the problem, resulting in acceleration of funds for its earlier decision to establish a permanent quarantine facility at the site (9). Ford remained an active participant in local activity, supplying the Quarantine Station with fresh produce, building sea baths and the first section of the Portsea pier to accommodate the Despatch, which was the area’s regular link with Melbourne on a weekly run to Lakes Entrance, plus other irregular vessels Williams and Golden Crown. He also established the Nepean Hotel, planting a park in front with the cypress pine trees still growing there; this hotel remained in the family with a short break until after World War 2. The early rural and lime-producing activities in the area were later supplemented by fishing, first for consumption by the local population, then expanding when some fishermen obtained licences to supply the Melbourne markets, their families adding to the growth of the bayside community. Sea access also eventually provided the means for Portsea to become established as a holiday resort in the 1880s, Williams now providing a weekly connection with Melbourne: it became a popular retreat for literati, academics and lawyers, plus a quota of remittance men paid by their English families to stay overseas (10). Then it also became the focus of a century long and continuing military connection.

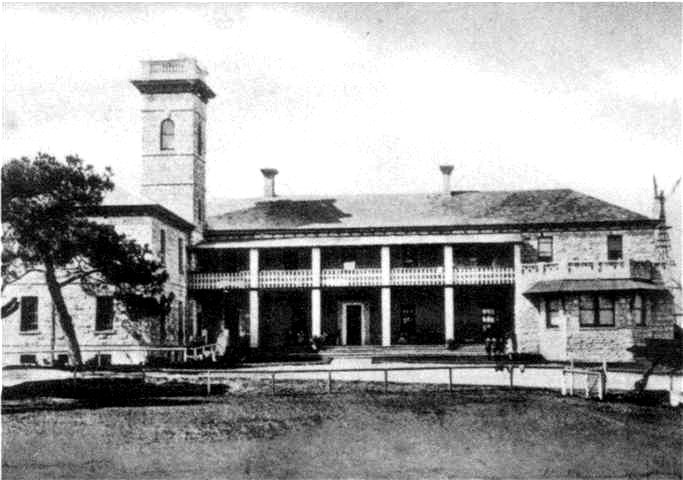

Built by James Ford, it underwent a series of changes and updatings to become in its later proprietor’s golden words ‘a first class Residential Hotel standing in spacious grounds, and embodying every comfort and convenience at a reasonable, flexible tariff’.

To those used to modem hotel-motel accommodation it was a relic of an old world era; to cadets at OCS it was a watering hole; and to those on an illicit weekend assignation, it was a place to register as Mr and Mrs Jarman, the name borrowed from the original instructor of that name.

Nepean Historical Society

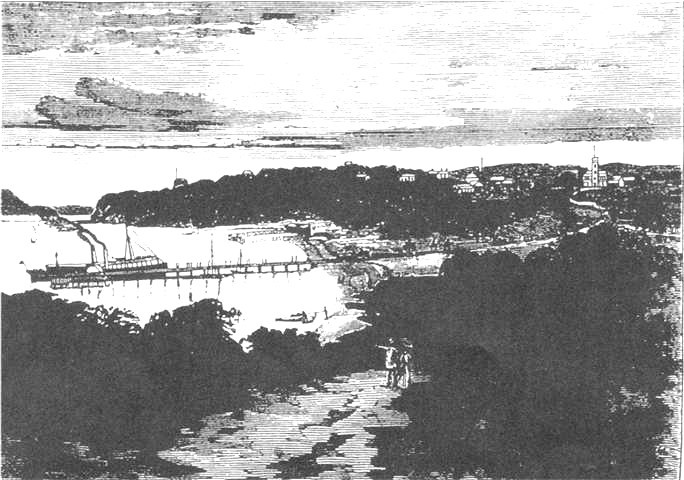

The lower bay provided attractions of open spaces, ocean and bay beaches, and a degree of isolation from the hustle of ‘Marvellous Melbourne’. Regular ferry services made feasible the trip to Portsea as an alternative to a two day sulky ride.

Then as now Port Phillip was the focus of water sports, while beaches, scenery, horse riding and walking were desirable get-away-from-it activities in a world without radio, cinema or TV, and from unsewered Melbourne, which accordingly earnt its rival Sydneyside epithet of ‘Marvellous Smelbourne’.

An array of hostelries in the district completed the scenery for holiday makers and residents alike.

Illustrated Australian News Supplement 18 December 1886

Forts and Training Establishments

Victoria’s first attempts at defence of Port Phillip began with establishment of a coastal artillery fort at Queenscliff near the western head of Port Phillip in response to the 1854 Russian scare, extended by 1862 to include other batteries at Williamstown and Sandridge. In 1877 visiting Royal Engineer Colonel Sir W.F.D. Jervois proposed a plan for comprehensive defence of the entry to the Bay which was taken seriously enough as, under the supervision of Colonel P. Scratchley, there were by 1880 two batteries erected at Queenscliff, another under construction on Swan Island, two batteries at Point Nepean in temporary positions and about to be permanently built in, and an artificial island under construction in the South Channel for another fort. By the time of the next substantive Russian scare in 1885 these works were mostly complete and a further battery emplaced at Fort Franklin, with subsequent work commenced on another artificial island to hold a fort at Popes’ Eye Shoal. The citizens of Melbourne obviously thought they had something worth protecting as by 1887, when the fortification’s armaments had had added to them the arming of Harbour Trust boats, provision of torpedo boats, minefields, searchlights, floating batteries, plus patrol vessels and telegraph wires for early warning, visiting inspector Maj Gen Schaw rated it ‘thoroughly satisfactory’, and an 1890 English version rated it ‘the best defended commercial city of the Empire’ (11).

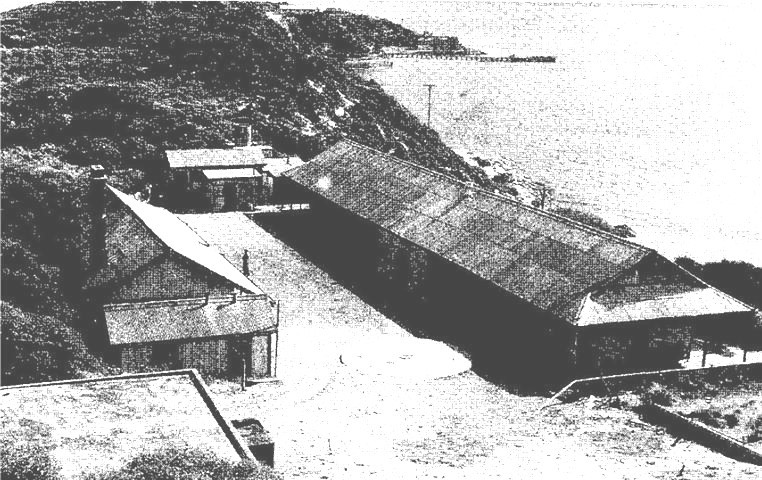

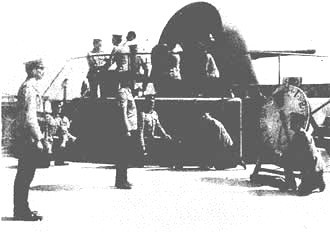

Part of the ring of guns and ships which made Melbourne one of the ‘best defended cities in the Empire’, Fort Franklin commanded the south passage up Port Phillip to the city.

Originally the permanent gunners who manned the fort were based at Fort Queenscliff on the western headland of the bay, but in 1894 Franklin Barracks was constructed to the rear of the fort to house the battery.

The fort went through later phases of inactivity, especially between the two world wars, revived for the latter, then abandoned with the closure of coastal artillery. The ordnance was disposed of, but fortunately most of the gun barrels were retrieved and mounted in the grounds of OCS.

Nepean Historical Society

The eastern forts were established at The Heads on a 420 acre defence reserve encompassing Points Nepean and Franklin, the former carrying one 9 inch and four 80 pounder guns, the latter three 80 pounders, in concrete emplacements with underground ammunition magazines and facilities hewn out of the sandstone, all protected against ground assault by Nordenfeldt guns. After a period of the gunners and engineers being based at Queenscliff and rotated to Nepean by launch, Franklin Barracks was established immediately to the south of Fort Franklin in 1894 to house the eighty members of the Victorian Permanent Artillery manning the eastern forts.

Beyond the Barracks is Fort Nepean with its jetty, covering entry through The Heads. This secondary barracks was built for gunners and engineers of the batteries at Nepean and Pearce in 1917. In World War 2 the buildings were occupied by AWAS who replaced male soldiers in the garrison, and was consequently known as the Wassery.

While the chance availability of Franklin Barracks for the Strathairdevacuation solved that problem, one of the standard summertime plans for evacuation of OCS in a Quarantine emergency was to use the limited Pearce Barracks for administration and training facilities, with marquees and tents erected nearby for cadet and staff accommodation.

Australian War Memorial Pll0B/13/09

Subsequently a new battery was established at Fort Pearce in 1911 and six years later Pearce Barracks was completed to accommodate the gunners and engineers in the Point Nepean area (12). One of the guns at Fort Nepean is credited with firing the first shots world wide from the British Empire side in both World War I and World War II, in the first instance challenging and stopping the pre-warned German merchantman Pfalz leaving port on the outbreak of war on 5 August 1914, then latterly at an unidentified ship entering Port Phillip on 4 September 1939 which turned out to be the Bass Strait freighter Wonoira (13).

The first guns were established on the eastern Head on a temporary basis in 1878 at Fort Nepean, with permanent emplacements developed two years later; Fort Franklin was added in 1885. Additions in both the Colonial and Commonwealth eras included the establishment of command and observation facilities, with underground magazines, internal power generator, and a pier to service the forts from the artillery headquarters at Queenscliff.

The original muzzle loaders were progressively replaced by breech loading and disappearing guns.

The gun position shown is the one credited with the imperial opening shots of World Wars 1 and 2. Its barrels are mounted at the entrance gates of the military reserve.

Nepean Historical Society

Facilities in the Nepean area were pressed into service for other military activities. The Quarantine Station was lent to two battalions of infantry for their 1881 Easter Camp. Fort Franklin also had other uses: as the only permanently staffed and catered establishment available to the Colonial and then Commonwealth military forces in Victorian Military District, and having a convenient training area within the defence reserve, the Barracks provided a venue for schools of instruction without requiring the usual overhead of setting up a special administrative structure for their limited duration. After Federation and the Commonwealth’s assumption of the Defence function, an additional area of land was acquired and gazetted in 1905. A School at Portsea and staff were established at Franklin Barracks to cater for periodic schools of instruction, Major R. Dowse being the first Officer Commanding and Chief Instructor, providing for courses including a 1911 special course to qualify officers for appointment to the permanent Administrative and Instructional Staff for the upcoming Universal Training scheme (14), foreshadowing Portsea’s future role in 1952.

In a change of policy to fully qualify and commission Australian Flying Corps pilots in Australia rather than sending them overseas as partly-trained NCOs, the School of Military Aeronautics (AIF) was established to carry out elementary flying training of flight cadets after which they completed their course at the Central Flying School, Laverton. The School of Aeronautics was located at Franklin Barracks under command of Captain H.H. Kilby: its first course was in December 1918, and it closed at the end of 1919. Thereafter the Portsea-Balcombe area was reinstated as a popular location for unit camps and courses of the militia 3rd and 4th Divisions and senior cadets, while Franklin Barracks was used for Militia schools of instruction, and for administration courses for Permanent cadre and 3rd District Base staff.

This use continued to 1942, when the belated realisation that parts of the country other than Sydney and Melbourne needed defending resulted in the militia divisions being redeployed to Western Australia and North Queensland. To replace these departing formations 9 Garrison Battalion (Coastal Defence) was located in the Defence areas of the Peninsula to guard an Italian prisoner of war camp and defend the forts, which were also adjusted by moving two guns from Fort Pearce to less exposed positions at Cheviot. And although the need for such major protection waned as the tide of war changed, the forts were used as a training ground for gunners and engineers destined for forward areas. Also stationed at Pearce Barracks was a company of AWAS, the female soldiers releasing males from signals, rangefinding and a multitude of administrative duties for deployment to active service areas. A supplementary activity for the area was also developed from 1943 when interstate ships due to join convoys at Hobson’s Bay were allowed to assemble at Portsea to save an unnecessary eight hours double journey to anchor off Point Gellibrand; they were permitted to come ashore to the township for rest and recuperation, and taking on stores and provisions (15).

Coastal artillery was disbanded after World War 2 when it was accepted that aircraft provided an effective and flexible solution to coastal and port defence, and were also on the other side capable of neutralising coastal batteries. This decision closed the forts at Queenscliff, Nepean and Franklin which were subsequently stripped of salvageable buildings and equipment, leaving Franklin Barracks without an obvious military function and in the hands of a caretaker, so there was no resistance by Defence to the Barracks being leased to the Lord Mayor’s Country Children’s Holiday Camp Trust in 1948 as accommodation for their youth camps (16). But while there was also obvious pressure for the now obsolescent Defence reserve to be opened up for development, the Army at that stage was unwilling to surrender any of its coastal properties and the value of preserving it also had strong local support, particularly from those already established in the area who had a vested interest in preserving their own preferred environment from hoi polloi. The Quarantine Station was also being superseded but a similarly conservative approach to retention of property in the Health Department opted for its retention as well. These conservative departmental approaches also meant that around Australia Defence reserves in prime urban and waterfront positions were saved from spoliation by property developers long enough for emerging popular awareness of their heritage and aesthetic value to exert pressure on governments to preserve them for the future. And in particular at Portsea both Defence and Quarantine reserves remained in place, to become an attractive national park site when changing departmental needs permitted.

Coastal artillery, a local defence battalion, an AWAS company, a prisoner of war camp plus the local administrative details established the need for a local medical facility.

58th Camp Hospital was established in a battlemented residence Dalgany House, occupied previously by the Misses Armytage and known locally as The Castle, to service the military presence in the Franklin-Nepean area.

Australian War Memorial 069144

Quarantine Station

A temporary timber hospital was built in 1854 to obviate future immediate problems of the desperately ill which had been experienced so dramatically in the Ticonderoga imbroglio, and ongoing problems of subsequent ships encouraged a more permanent solution. Construction of the Sanatory Station proper commenced in 1857, resulting by 1859 in five two-story rough-cast stuccoed sandstone ‘hospitals’ each with slate roofs, verandas, balconies and four 60×20 ft dormitories, to provide extended accommodation for disembarked passengers. Initially non-discriminatory, they were subsequently allotted one each for first and second class, two for third and steerage passengers, with the fifth by 1884 being allocated as an isolation hospital for those with communicable diseases, No 1 then being refitted for first class passengers as part of the ongoing upgrading programme. There were also ancillary buildings for office, stores, kitchen, dining, laundry, staff quarters and a crematorium. A police station was set up in 1852 to control isolation of the Ticonderoga disembarkees, and from the 1854 gazettal of the Station, the Quarantine reserve of 957 acres was created to both contain the Station and provide a buffer zone to assist police enforcement of isolation. Further building extensions in 1879 resulted from a co-located leprosarium, animal quarantine area and consumptives’ camp to the west of the quarantine station. Subsequent extensions included a two-ward infectious diseases hospital and administration buildings in 1915-16 and 12 weatherboard huts in 1919 as emergency wards for a procession of 12,000 soldiers returning from World War 1 isolated as a result of the Spanish influenza pandemic which they brought back from the Continent. Various smaller service buildings were added during the life of the Station, the last being two observation wards in the early 1970s during OCS’s occupancy (17).

The Nos 1 and 2 Hospitals are depicted, with some artistic licence, as being much wider than they were. Each was to a similar design, except that the dormitories in these two were subsequently partitioned into private rooms to cater for the 1st and 2nd Class passengers.

When the No 1 building was burnt down in 1916 it was rebuilt the following year to a better standard, reflecting the perception that First Class passengers were entitled to similar standard accommodation ashore as they were afloat.

Australasian Sketcher 29 September 1877

Originally water traffic into the area was by small boat across the beach, but growth of the lime trade serviced by a fleet of 30 to 40 ton craft required jetties to load them. The Quarantine Station was served by its own pier on Ticonderoga Bay while a supplementary wharf to unload large animals for the animal quarantine reserve was located at Observatory Point. The heavy returning traffic of servicemen from Europe from 1915 onwards brought renewed interest to quarantine activity, resulting in the additional buildings mentioned previously, and with the very regular flow of troopships which brought repatriated soldiers on their return journeys the Nepean, a 42 ft vessel built at Williamstown in 1917, was brought into service at the Station on a permanent basis rather than the previous chartered or borrowed vessels (18).

The group is awaiting disembarkation to the quarantine station for fumigation during the virulent influenza pandemic which returning servicemen brought home with them from Europe.

Soldiers pelted Quarantine officials with rubbish to stop them boarding, as the last thing they wanted was further weeks in isolation before getting home. The Station boasted of never having been repulsed.

Those found to be infected were housed in twelve temporary huts which were built for the occasion and survived over thirty years later to provide temporary training facilities for the Officer Cadet School.

Australian War Memorial J02824

Throughout its existence the Quarantine Station saw many changes and improvements, as much as its medical superintendents had bemoaned official lack of interest in quarantine unless a substantial scare was in train. The final configuration of the area as described by the army reconnaissance party investigating its suitability for the proposed Officer Cadet School was (19):

- First Class passenger accommodation – two two story buildings each with large rooms with cupboards and hand basin, lounges at each end and internal showers and toilets with adjoining dining rooms and kitchens;

- Third Class passenger accommodation – two two story barrack style blocks each able to hold 60 dormitory style, with internal cold water showers and toilets and a separate kitchen and dining room for 100, and a separate large steam laundry plus hot water bathing facilities for 60 at a time;

- An isolation area of the fifth accommodation block, similar to the First Class ones;

- A hospital, an administration block of offices and other functional buildings.

These facilities were shared by the joint Officer Cadet School-Quarantine Station, the

School progressively taking over more buildings as the Quarantine need receded, until the latter was finally closed on 29 September 1978.

Environmental Interests

While occupation of an area by Defence eventually attracts the attentions of those seeking to profit or benefit by its removal, the residents of Portsea early recognised that their environment was enhanced by having a low-use resident excluding close development or the introduction of noxious activities. Their environmental concerns embraced both self interest and altruism, local residents valuing the isolation and beauty of the area for their own living ambience and for the peninsula generally. This symbiosis of local and governmental interests meant that the quarantine and defence occupation was unchallenged locally, other than for periodic complaints where residents either felt unduly impeded in their use of the bayside facilities or considered that the reserves were not being adequately maintained or protected.

Such incidents included a diversity of interests:

- in 1919 Captain Kilby of the Aeronautics School drew fire for erecting a new fence cutting off a walkway along beach and cliffs where the public ‘always had right of way’, which was conceded and an easement allowed;

- a Mr Goss who had willingly allowed a resumption of land in 1905 asked for and received back in 1920 a 3 metre strip to complete a building block;

- from 1960 representations were made for restoration of the cemetery which was finally brought under proper maintenance;

- and while a 1952 complaint by a resident on burning of bushland drew a tart response by the Minister for Army that the clearance of a range to minimise fire risk involved low impenetrable scrub in an inaccessible area which was not a beauty spot, the School was also enjoined on other occasions to keep rigid control of such activity to minimise problems

There remained an underlying desire within Army Headquarters and Headquarters Southern Command to ensure that the activities at OCS would not jeopardise ongoing occupancy of such a desirable site. Commandants were instructed, and were themselves highly conscious of the need to be responsible occupants and a valued component of the local community (20).

This did not always run as smoothly as could be desired, if for no other reason than financial problems. Point Nepean had always been under pressure from the waves, both on the sea side and within the bay, so in colonial times extensive retaining walls were built for several hundred metres to prevent a breakthrough which would allow sea pressure to build up the level of Port Phillip, flooding low lying areas, possibly including Melbourne itself. Continuing battering and erosion required continuing maintenance, which was done on a minimal basis, the Commonwealth always angling for the State to maintain the walls, the State angling for Commonwealth funds. During OCS’s occupation of the area, maintenance of the sea walls remained an ongoing problem, culminating in 1967 when a survey showed that erosion had reduced the crest at the narrowest part of the neck to ‘feet rather than yards’, with a breakthrough imminent. A joint effort prevented this but the wrangling continued, the Commonwealth steadfastly declining to assume prime responsibility for natural activity (21).

The sea walls on the Rip and bay, and the narrow isthmus joining it to the main peninsula are clearly shown. The walls had been in existence for 80 years, periodically torn down on both the sea and bay sides by waves and tidal action. They were rebuilt, and during World War II Italian prisoners of war were employed weaving mats of grass and reeds to cover the sand dunes against wind erosion.

The consequences of a breakthrough flooding low lying Melbourne suburbs may have been overstated as some technical opinion considered that the residue would be a tidal reef no different to that beyond the Point.

RMC Archives

Another bone of contention was the cemetery. Of the original occupants from the Ticonderoga, 82 died after arrival and were buried on the foreshore near the subsequent site of No 3 Hospital, many without coffins simply interred by collapsing sand cliffs over them. These graves were exposed by successive sea erosions so the remains were reinterred in 1952 in the Point Nepean cemetery located in the Defence reserve, which also contains the graves of early settlers including pioneers James Ford and Edward Skelton, fatalities from the Tornado quarantining in 1869, and sailors drowned in the wreck of Cheviot in 1887 at The Heads. The cemetery was closed to the general public in 1890 with the opening of Sorrento General Cemetery, but it continued to be officially available to both Quarantine Station and military personnel using Franklin Barracks and the training areas in the Defence reserve; the Victorian Secretary of Lands in 1912 had made a blasé remark that ‘in the event of bombardment of Point Nepean, this cemetery will be the most convenient in which to bury the killed’. Up to 1962 there were 22 additional interrments from the Quarantine Station, including one of the returnees from World War 1 quarantined in the influenza epidemic who occupies an official war grave; in addition there were four private burials of local residents. Soldiers returning from the Boer War in 1902 on the trouble-plagued Drayton Grange were isolated at Fort Franklin on arrival; five died of bronchopneumonia but strangely were buried in Sorrento General Cemetery rather than the one on the Defence Reserve which was retained specifically for military and quarantine use; a single tombstone stands over their graves at Sorrento (22).

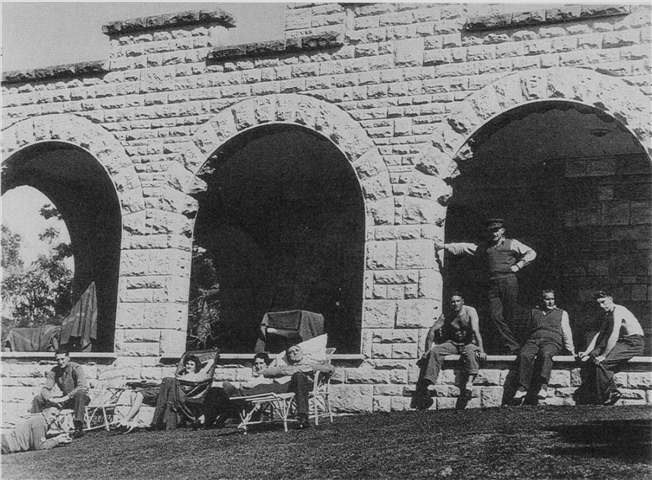

The cemetery restoration work was carried out by OCS staff members who, having committed misdemeanours, were available for extra duty employment and served this to good purpose restoring historical sites in the reserves. There was also cooperation from Quarantine staff, here assisting by cleaning grave sites and repainting grave markers.

The staff’ had their own distinctive uniforms, and to cadets were a familiar sight in the area.

Nepean Historical Society

With disuse and the multi-departmental occupancy and responsibilities after OCS took up residence, the cemetery fell into such disrepair that from 1960 locals raised increasing complaints on damage to the graves, culminating in 1964 with an on site meeting of the Federal member for Flinders Major R. Lindsay, representatives of the Department of the Interior and Headquarters Southern Command, and three local citizens to resolve demands that the Department of Army restore and maintain the site, but this and subsequent approaches to both minister and department brought further evasion rather than action. Finally as a matter of personal interest in the historic site Maj J.H. Welch, major in charge of administration and local historian, had it cleared and restored by volunteer conscripts of the OCS administration staff; as he succinctly put it:

what politicians and public servants could not accomplish was achieved by dint of sharp machetes and strong right arms. For once the sword became mightier than the pen.

As an extension of the lawns and gardens of the area, it stands as part of the record of those who made and passed through the area in the previous century and a half (23).

From the original settlers’ occupation, only the shepherd’s hut of the 1840s remains. Of the rest, the foundations and garden of a limestone cottage are still visible beside the magazine. The post-war stripping of the Point Nepean and Franklin Forts has left a series of underground storehouses and magazines plus the empty gun emplacements, the former of which has been partially restored and is now part of a scenic walk in the Point Nepean National Park.

The Campus

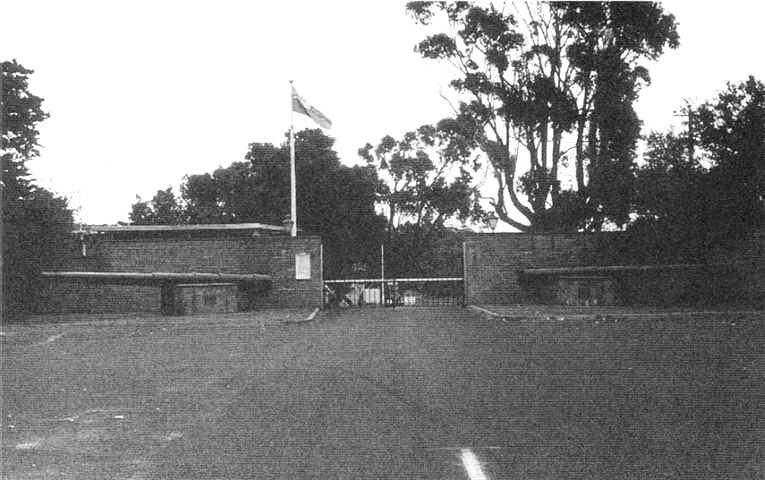

Entrance to the Officer Cadet School was through impressive walled gates erected for the Quarantine Station and bearing its crest and sign. With OCS’s advent its badge and sign were added, and in 1967 two gun barrels were mounted on each side of the entrance; after the closure of the Quarantine element in 1978 the School signage was rearranged to occupy both sides of the entry. The 6 inch Mark 7 breech loading barrels of the guns which formed the Nepean Battery, including the ones credited with firing the first allied shots of the two world wars, were dispersed after World War 2, as was unfortunately our wont with important artifacts. One was transferred to the Proof and Experimental Range at Port Wakefield for use in testing large calibre ammunition, the other sold for scrap. But in 1965 Maj J.H. Welch instituted a move to recover them, one fortuitously discovered in the Melbourne yards of a scrap dealer Stern Industries and brought to Portsea by RAASC tank transporter from Puckapunyal, the Port Wakefield one similarly retrieved. The Army Apprentices School at Balcombe diverted the talents of some of its students to refurbishing and mounting the two barrels outside the front gates of the School where they provided a military flavour to the Quarantine Station entrance and retained notable historical relics connected with the area in a position which, if not ideally their original location, was at least nearby and protected from the depredations to which they would otherwise have been exposed (24).

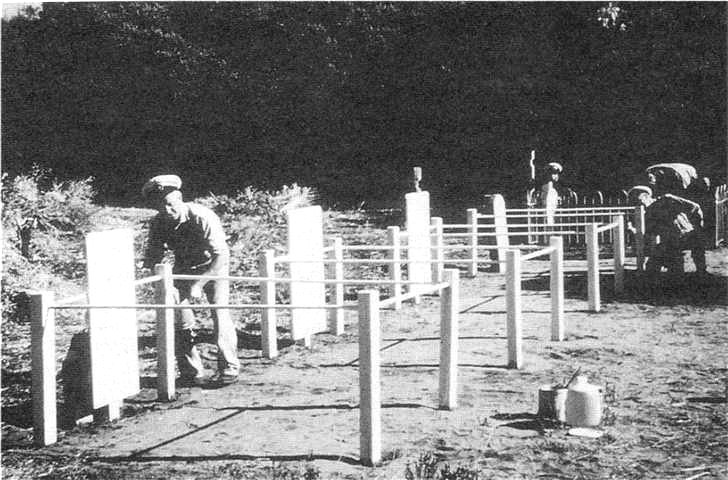

The ‘first shot’ barrels were recovered, one from Port Wakefield and the other a scrap metal yard; wooden plinths to mount the barrels were constructed at Army Apprentices School, Balcombe with bronze plaques recording the history of each gun attached to the mounting bases.

Minister for the Army Phillip Lynch, also local member of parliament, unveiled the guns at a ceremony whose guests included the gun layers involved with the firing of the first shots in each war, Mr J. Purdue from 1914 and Mr S. Walsh from 1939.

OCS Scrapbook 1972

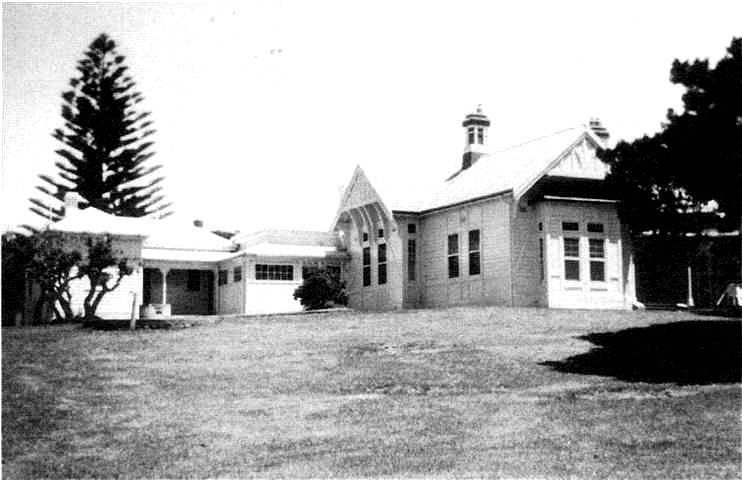

The entrance road passed a series of living quarters, originally built for the quarantine staff and progressively taken over for use by the military staff. Amongst these was The Bungalow, built as the Superintendent’s residence in 1899 and possibly incorporating the original 1854 doctor’s cottage (25). This was used as an isolation hospital for occasional patients during the OCS period, eventually becoming the residence of the Commandant. Past these buildings was the beginning of the Quarantine Station functional buildings, the first being the accommodation blocks. The initial allocation of facilities for the temporary housing of the School in 1952 comprised four of the five accommodation blocks plus some ancillary buildings for training and administrative purposes, the Department of Health staff retaining the No 2 accommodation block, isolation hospital, administrative offices, store and dwellings for its own use. Pressure on the accommodation facilities, first for the extended course, realised a transfer of No 2 block in 1955, then in the mid-1960s expansion two new blocks were built in 1963 and 1965. The new blocks lacked the ambience of the original ones, but were of similar shape to complement the architectural theme, and were purpose designed as individual suites for the students.

Possibly incorporating the original 1854 doctor’s cottage in the middle, this building was finally brought to its present structure in 1909 as the Superintendent’s house. It was subsequently used as the isolation hospital for occasional patients from ships and aircraft during the OCS period, after other buildings had been given over to assist in the expansion of the School.

It was more than adequate for most incidents, avoiding the necessity to clear major buildings for other than the two major emergencies in 1954 and 1957.

After the Station closed in 1978 it was the Commandant’s residence, a mixed blessing as the rambling house with large rooms swallowed the normal furniture owned by its occupants.

Nepean Historical Society

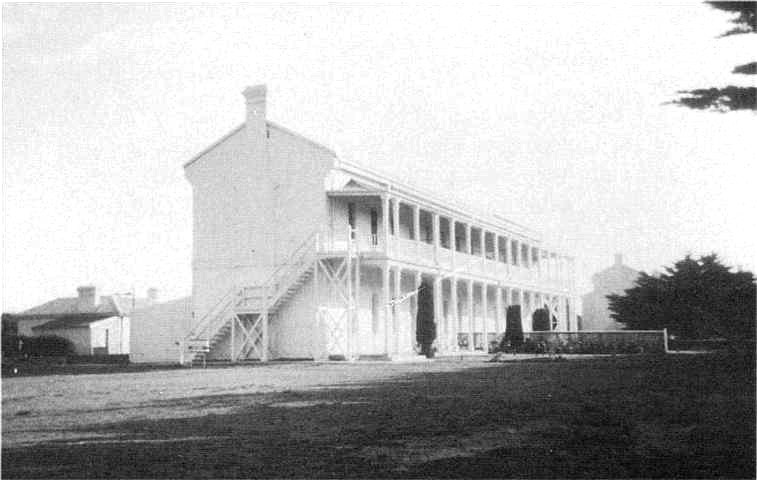

The five identical accommodation buildings known as hospitals, built 1857-59 in a colonial barracks style, were strung in line along the axis of the Station parallel to the beach. Each consisted of four 25-passenger dormitory wards, giving an initial capacity of 500. No 1 Hospital was first used for infectious cases but this was changed to No 5 in 1884 after which the former was altered to individual rooms for first class passengers; No 2 was similarly changed internally in 1909 and some partitioning was also effected on the ground floor of Nos 4 and 5 by 1919. When No 1 Hospital burnt down in 1916 it was rebuilt with a more comfortable standard of recreation facilities the following year, and it was this building which the early cadets inherited, albeit at two to each room; its adjacent dining room and kitchen became the cadet’s mess and was expanded in 1965. No 2 hospital as mentioned became the second cadet accommodation block; No 3 the other ranks quarters, store and armoury; No 4 other rank quarters and recreation facilities; and No 5 the sergeants quarters and mess, and quartermaster store (26).

Original permanent blocks completed in 1859 with 100 bed dormitories and staff quarters, they were reallocated by 1884 as steerage and isolation accommodation respectively, the latter being surrounded by a galvanised iron fence for security, and later supplemented by a fully separated isolation hospital and supplementary kitchen and sanitary buildings.

No 4 block became the other ranks quarters and recreation facilities, for years plagued by a leaking roof and local wildlife until repairs belatedly restored it to a livable state. No 5 was the sergeants quarters and mess, and quartermaster store.

The building at the rear of No 4 was converted to classrooms, augmented by portable ones as the School grew in numbers.

Nepean Historical Society

Below the cadet accommodation complex is perhaps the oldest building relic, now submerged in an underground dairy with sandstone cottage above it. There may have originally been a wattle and daub hut, part of the Hobson’s 1838 Nepean to Boneo grazing property on which he ran sheep: resulting from an early Sydney magistrate’s decision a shepherd was employed to look after each 400 throughout New South Wales, and local tradition called it the Shepherd’s Cottage so it possibly housed those in that part of the run. The existing limestone building was constructed before 1854, being used as a staff dwelling until converted to a dairy in the late 1880s on the initiative of resident doctor J.H. Browning; cows were milked in the building with produce processed and stored in the cellar. Later it was used as an office and store, the cellar falling into disuse until 1941 when it was rediscovered and allotted as an air raid shelter. The building, strategically overlooking the parade ground, finally became the office of the Regimental Sergeant Major of OCS (27).

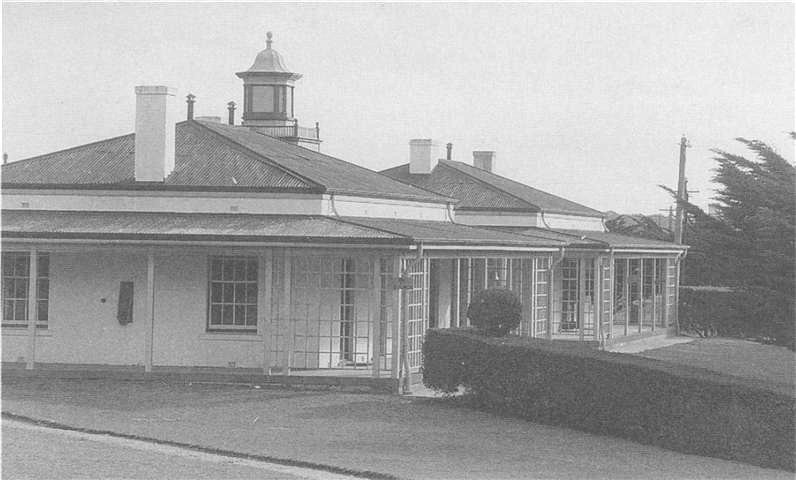

The next of the early structures is the 1916-vintage administration building, which incorporated offices and living and dining facilities for attendants, nurses, police and visitors, together with a doctor’s surgery, dispensary and post office; it was converted by OCS into the School Headquarters and Officers Mess (28). Between this complex and the cadet accommodation a lecture and library facility was built in 1963, named Badcoe Hall four years later. And between this and the Shepherd’s Hut, overlooking the parade ground, a memorial to graduates who died on active service was unveiled in 1967.

From its 1916 opening the building became the focus of the Station, with a clock tower which could be seen from most of the station, which was useful until the clock was removed.

It was a multi-purpose structure in two parts, the front incorporating offices, doctor’s surgery, dispensary and post office, the rear living and dining facilities for police, nurses, attendants and visitors.

It was subsequently converted to the headquarters of the School with the rear becoming the officers mess, which functions remain in the School of Army Health.

Photo: B.H. Cooper

In the early stages the School was without a gymnasium until one was completed in 1966 behind No 3 block. From near the back of this a track runs 200 metres from the magazine to the top of the hill which also provided the venue for the OCS Scramble Track, to an open brick crematorium probably last used in 1926. To the side of the gym is a cottage, erected about 1913 near the general store but relocated in 1925: used initially as a dispensary, consulting room and post office, then a maternity ward, it was designated Cape Cottage by OCS and used to accommodate distinguished visitors; and close by are the 1916 concrete flammable store, and another used as a pay office and reproduction centre. On the other side of the gymnasium is the transport office and transport compound, the former occupying a 1916-era building used as stables, beyond which are the weatherboard 1919 emergency wards, used variously by the School as wet weather instructional facilities, miniature range, offices, stores and workshops (29).

Supplementing the initial 1866 stone open bath and wash house, this sombre brick building was a high capacity bathhouse in the Victorian style, on either side of a central laneway, used as part of the decontamination progression. Luggage, mail and clothing went through the infected receiving store, disinfection building, clean luggage store; humans went through the waiting room, bathhouse, and accommodation cycle or on to isolation.

It must have taken a certain degree of imagination and desperation to see in the twin bathhouses the potential for cadet living accommodation, but less than that of the cadets who thought they looked like terminal care wards, even by late Victorian standards.

Nepean Historical Society

In front of No 3 block is the decontamination complex, of mostly 1900s vintage: adjacent to the beginning of the 1858 pier, it starts with a 1911 waiting room, leading on past an 1866 stone bath and wash house, through an infected receiving store and disinfection building with accompanying boiler house, to a clean luggage store; beside these are two bathhouses and towards the shore a 1925 supplementary shower block. The pier was demolished as unsafe and unrepairable in 1972, the stone bathhouse was pressed into service as a ration store, and the bathhouses became Death Row: converted to provide overflow accommodation in the 1970s, it was erroneously thought that the buildings had been a refuge for the dying and so the epithet. The decontamination building has been retained as a Department of Health museum housing relics of the quarantine station, and the clean luggage store, together with an adjacent later constructed building, were used as storehouses (30).

Built in 1854 to facilitate the disembarkation of passengers and service the Station, it was an integral part of the operation of the facility. But as the Quarantine Station was relegated to reserve status in the post-war years its maintenance was kept to minimum levels and the pier fell into serious disrepair, which neither Department of Army nor Health was willing to remedy.

The economical solution of demolition was agreed, and so in 1973 the Pier disappeared from a scene of which it had been an integral part for almost 120 years, just a little before the resurgence of conservation pressures in the subsequent decade could offer the possibility of reprieve.

Photo: R. Bricknell

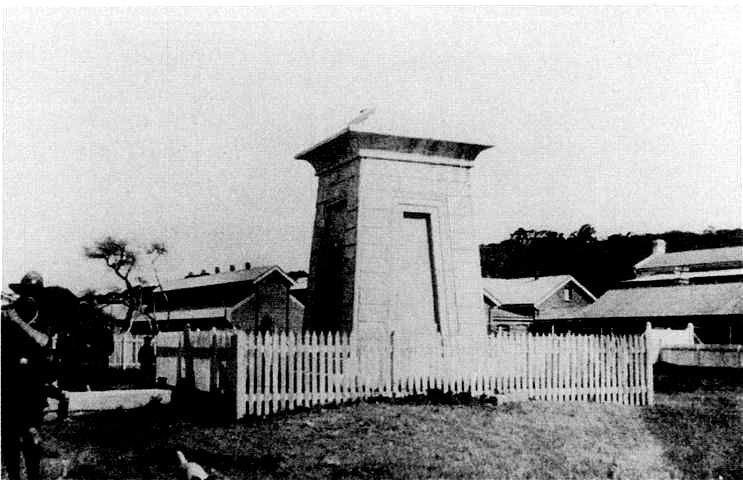

To the west of Death Row by the shore is the area where the original Ticonderoga interrments were effected, now marked by a monument erected by George Heaton, construction supervisor on the Quarantine Station’s initial buildings. As it has a vault it may have been intended as a family crypt, however this has not been used for any interrments but has been filled by sand drift. It is called Heaton’s Monument and has been suggested as being for the Ticonderoga victims, but the dedication panel carries no inscription. A more obvious answer is that Heaton, who paid for it, intended to be buried there, but as the existing remains were transferred to the Nepean cemetery, it was no longer in a cemetery therefore unusable, and he was interred in Melbourne (31).

On the foreshore with the decontamination complex and No 3 Hospital in the background, the monument has stood since about the end of the major construction effort in 1859. George Heaton was a construction supervisor and erected the edifice at his own expense for a purpose which is not certain.

Thought by some to be a monument for the Ticonderoga disaster, it has a crypt underneath, now filled by sand. This suggests that it may have been intended as a mausoleum, though it was not so used and Heaton lies in a Melbourne cemetery. The inscription panel carries no message, so its purpose remains an uncertain.

Nepean Historical Society

To the rear of No 4 block were established a series of relocatable classrooms and an office building for education officers. No 5 block, after its 1884 translation to infectious diseases, by 1920 had around it a series of satellite buildings: a fenced-off two-ward isolation hospital, with attendant staff changing rooms, mortuary and laboratory, and an administrative block and kitchen. The administrative centre was converted by the army into a medical centre, while at the end of the quarantine requirement the isolation wards were used as offices for instructors. Beyond these buildings was Jarman Field, named after the deceased first instructor, for field sports, incorporating two ovals, and beyond them the sparse remains of the cattle quarantine, leprosarium and consumptives facilities (32). To the south of the centre road which traversed the peninsula was a conglomerate of training facilities: confidence course, assault course, and an array of ranges: 25 metre, classification, grenade, snap, sneaker, anti-tank, and shooting gallery. The remainder of the Defence Reserve constituted the close training areas for fieldcraft, minor tactics and physical training endeavour. Included in the Reserve are the Forts Nepean and Pearce sites, and Cheviot Beach where Prime Minister Harold Holt met his end.

As would be expected in a military academy, the campus attracted an array of past military equipment of both historic and decorative impact. Apart from the barrels at the entrance gates, a 10 inch disappearing gun which had been sited at Eagles Nest at Fort Nepean in 1889 was found half buried in the sandhills and mounted at the junction of the Defence and Quarantine roads in 1976 where it was joined by a Sherman tank which saw service in the post-war period christened Casper, giving rise to the name Tank Junction. A Matilda tank, an infantry support vehicle used in World War 2 from New Guinea to the Borneo campaigns, was located next to the School headquarters and field guns of various vintage were placed around the parade ground.

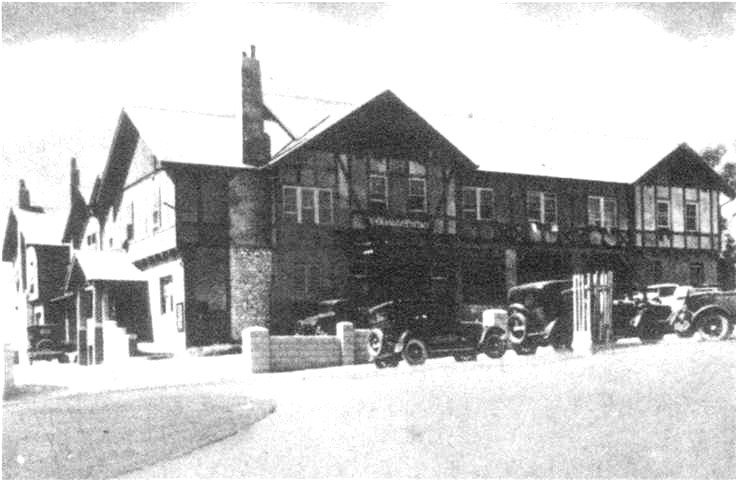

Portsea Hotel – 1930s

One of the holiday hotels of the area, it was much patronised in an era before holiday apartments, when all-in tariffs were economical and a usual means of taking accommodation by the sea.

To the OCS cadets it was one of several convenient hostelries which provided their basic source of alcohol and entertainment in the dry years, a watering hole to dash to after work on Fridays when drinking was legal, and yet another different pub when drink was freely available at the School mess.

Nepean Historical Society

This brief description of the area covers a great deal of ground in an extensive and fascinating area within which the Officer Cadet School operated for over three decades. Brevity has forced omission of many of the nuances of the background history, and the OCS usage of facilities was more fluid than has been represented, as changing needs and availability of buildings forced or encouraged alternate uses. It was both a great benefit and a privilege for the School to have been endowed with such an outstanding campus: the Portsea area was connected with the early discovery and settlement of Australia and development of the Port Phillip District; it formed part of the maritime defence system and provided an ongoing training facility for the Colonial and Commonwealth forces; its natural environment made it an extremely beautiful site; its core buildings were steeped in history and heritage; and it was in a community which both appreciated and supported its existence. The site has now been passed on to other uses which preserve both the heritage and environment.

Few establishments boast a private beach, but being inside a restricted area, the beach under the cliff below the cadets’ accommodation block was secluded and free of visitors. Had the water and weather been kinder it would have been even more attractive, however with only afternoon sun when there was sun, and water at normal swimming temperature for a few weeks of the year, its use was limited, here G.H. Nicholson braves the cold.

It had another use as an escape route much frequented by cadets, especially the married ones getting home in the days when no leave was given other than the odd weekend. High tides made the way precarious for these night time travellers who had then to climb around the rocks.

Photo: D.J. McLachlan

References

- Macintyre K.G. The Secret Discovery of Australia, pl43-8, 148f; Bonwick J. Discovery and Settlement of Port Phillip, p5-8; in Homer F. The French Reconnaissance, p214 – the course shows that the Baudin map published nine years later owed much to Flinders’ and Grant’s earlier charts.

- Tench W. Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay, p22; Clark C.M.H. A History of Australia vol l, p182-3, 190, 197-8.

- Bonwick, p10f; Hollinshed C.N. ‘The Nepean Peninsula in the Nineteenth Century’ Victorian Historical Magazine v28 No 4 December 1958, p146-50; Historical Records of Australia III.l Collins to King 5 November 1803, p33f.

- Sullivan H. An Archaeological Survey of the Mornington Peninsula, Victoria, p54, 118; Moorhead L. In the Wake of Flinders, p30; HRA III.1 Journal of the Proceedings on Board Her Majesty’s Ship Calcutta, p98 and Memoir of a Chart of Port Phillip by Lieutenant James Tuckey, p118f; General Orders, p523 and Note 267; Turner H.G. A History of the Colony of Victoria vol I, p37 -8; Fawkner’s Reminiscences in Hollinshed ”Nepean Peninsula in the Nineteenth Century’, p153.

- Sullivan Momington Peninsula, p14-18, 21-2; HRA Ill.1 Memoir, p121; Turner, p217-22.

- Sullivan Mornington Peninsula, p29-30, 34, 120.

- Hollinshed C.N. Land, Lime and Leisure, p66-7.

- Hollinshed ‘Nepean Peninsula’, p50-3, 66f, 121; Rogers H. The Early History of the Mornington Peninsula, p61-2; Welch J.H. Point Nepean – Portsea, p4.

- Hollinshed ‘Nepean Peninsula’ p171; O’Neill F. Point Nepean: A History, p24-6.

- Hollinshed ‘Nepean Peninsula’ p190-7.

- Victoria Year Book 1880-81, pl1-12; 1883-84, p597; 1885-86, p660-11; 1886-87, p815-16; 1888-89, p462-63;PP Vic LA 1885 vol 4 Commandant’s Report, p5; O’Neill Point Nepean, p46.

- O’Neill Point Nepean, p52.

- Welch J.H. Portsea, p10.

- O’Neill Point Nepean, p50; AA MP 84/1 2002124/194 of 3 April 1911; Military Orders 101/1911, 252/1911.

- Military Orders 138/1918, 437/1918, 4971918, 505/1918, 57811919; AA MP701/6 27/1411504 of 1 July 1937, 1 June 1938; AWM 49 Serials 99, 178, 190; AA MP70/5 27/14/1504 passim; MP1049/5 2026/12/524 of21 March, 14 June 1943.

- Letters Nepean Historical Society of 29 June 1995.

- Welch J.H. The Peninsula Story Part 2 Hell to Health, p45-7, 523, 55; O’Neill. Point Nepean, p29-31; Finn C. A Point to Remember, p10; Power S.M. ‘Maritime Quarantine and the Former Quarantine Station, Point Nepean’, p175.

- AA MP641/1 35/4 of 23 August 1916.

- AA MP 927 A259/18129 DMT 1019 of 5 July 1951.

- AA MP367/1 481/16147 517/1/636 of 23 February 1920;AA 927 A82/2/1 of 7 February 1952; R371/1/1 of 14 July, 30 July 1971; R7/1/2 of 11 September 1972.

- AA B2453/1 R750/619 of 6 May 1988.

- Welch Portsea, p7-8; ‘Portsea Quarantine Station and Defence Reserve’, p7-8.

- Welch Peninsula Story, p44-5, 86;.McGregor K.R. ‘Grim Reminder of Past Activity The Cemetery’ OCS Journal June1972, p38-9.

- Welch Portsea, p11.

- Power, p187-91.

- Power, p160f.

- Power, p113, 197-9.

- Power, p119f.

- Power, p203-7, 210; Letters Nepean Historical Society of 29 June1995.

- Power, p174-181.

- Power, p207; Welch Portsea, p7.

- Power, p184-6, 207.