Critical Reading

by Tarasa Gardner and Jeanne Bastian

Critical reading, simply put, means thinking about, analyzing, and questioning a text before, during, and after you read it.

Important considerations for critical reading:

Critical reading is active. Active reading means that you engage with the reading: mentally, by thinking about what you read, and physically, by jotting notes in the margin, looking up unknown words and writing their definitions, writing down questions that arise as you read, and summarizing (condensing an author’s key points or ideas in your own words) or paraphrasing (restating an author’s idea in your own words and sentence structure).

Skim for principal ideas

- Preview the length of a work so that you have an idea of how much time you will need to read it and what the key ideas are.

- Next, preview the title, headings, first sentences in paragraphs, words in bold, and any illustrations, photographs, charts, or tables to help identify the author’s key ideas.

- Read the concluding paragraph or summary of the text to reinforce the principal ideas.

Read for comprehension

- When reading for comprehension, read for the author’s main ideas. Try to comprehend the essence of the text, making sure to mark any section that you don’t understand.

- During this reading, take your time and annotate (write notes in) the text. Look for the author’s main point (thesis) and supporting details, and make sure to define any unknown words.

Summarize for recall

- After you read, summarizing an author’s main points in your own words can help you remember them. In a summary, focus on writing the main ideas and principal supporting details; you may omit detailed evidence here. The point is to help you gain mastery of the ideas.

A. Bloom’s Taxonomy

Developed by Benjamin Bloom and a group of educational psychologists to identify important learning behaviors, Bloom’s Taxonomy contains six increasingly complex levels of critical thinking skills. The taxonomy can help readers develop the habit of thinking about an author’s ideas, evidence, and reasoning, rather than come to quick, superficial conclusions about texts. The following six levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy comprise the revision that Lorin W. Anderson and David R. Krathwol devised in 2001.

Level 1: Remembering

- At this level, readers recall facts and basic concepts. Common questions used at this level are who? what? where? when? and why? Students recall and recognize at level 1.

Level 2: Understanding

- At this level, readers explain ideas and concepts using their own words. Explaining, summarizing, and paraphrasing a reading selection show that readers understand what they have read. Students interpret, give examples, classify, summarize, infer, compare, and explain at this level.

Level 3: Applying

- At this level, readers can use information in new situations, or they can solve problems with it. Finding the main idea or the organizational pattern in a reading falls in this category. Students execute tasks and implement knowledge at this level.

Level 4: Analyzing

- At this level, readers make connections between ideas, and they separate something into its parts or elements to better understand it. Comparing and contrasting, differentiating major and minor details, and distinguishing between facts and opinions are examples of analyzing. Students differentiate and organize at this level.

Level 5: Evaluating

- At this level, readers can justify a stand or a decision. Weighing evidence an author has used to support a claim and deciding whether or not to agree is evaluating. Students check (does this make sense?) and critique (does this author support the main ideas well?) at this level.

Level 6: Creating

- At this level, readers create original or new work or draw original conclusions. Making predictions or synthesizing sources into a new idea are both examples of creating. When writing a paper, you use level 6. Students generate, plan, or produce at this level.

B. Increasing Your Reading Rate

Chunking is a strategy for increasing your reading rate. It involves taking a lengthy, complex sentence or passage and grouping it into phrases and clauses according to their meaning. Grouping words into units according to their meaning increases both your comprehension and your reading rate.

If we look at these sentences from Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel, we can see how chunking works:

We all know that history has proceeded very differently for peoples from different parts of the globe. In the 13,000 years since the end of the last Ice Age, some parts of the world developed literate industrial societies with metal tools, other parts developed only nonliterate farming societies, and still others retained societies of hunter gatherers with stone tools. (13)

Experienced readers don’t read these sentences word by word; rather, they might break into phrases and clauses like this:

We all know

that history has proceeded very differently

for peoples from different parts of the globe.

In the 13,000 years since the end of the Ice Age,

some parts of the world

developed literate industrial societies with metal tools,

other parts developed only nonliterate farming societies,

and still others retained societies of hunter gatherers with stone tools.

To develop the skill of chunking as you read, make a conscious effort to group words and phrases together according to their meaning. The more you practice chunking, the more words you will be able to put in a meaning group, which means you will both read faster and comprehend better. Remember that punctuation can be a helpful tool in chunking, because commas, semicolons, dashes, and periods all indicate logical units of thought.

C. Using Context to Define Words

Using context means that we use the words and sentences around an unknown word to figure out its meaning. By consciously thinking about sentences that come before or after an unknown word, we can often determine its meaning so that we don’t have to consult a dictionary every time we encounter a new word.

Synonyms, antonyms, and examples are three common context clues, and often we can recognize of each of them by typical introductory words or phrases.

Synonyms are words that have the same or similar meaning as the unknown word—elated and joyful are synonyms.

In addition to synonyms, authors may also use comparison (showing similarities) or definition to clarify an unknown word. Common words that tell us an author is using comparison or definition may include like, also, as well, in other words, means, i.e. (that is), similar to, and similarly, as in:

Josie’s attendance is sporadic, i.e., some days she’s here and some days she’s not.

From this example, we may infer that sporadic means “random.”

Also, marks of punctuation such as dashes and parentheses may indicate either synonyms or definitions.

Goats and raccoons are omnivorous (animals that eat both plants and animals).

Antonyms are words that have the opposite meanings—rare and common are antonyms. Often, authors will use antonyms to define unknown words, such as

Mary was outgoing, but her sister Sarah was diffident.

Here we can see that outgoing and diffident are contrasted, so we are able to infer that diffident means “shy.” Common words and phrases that indicate contrast include but, rather, yet, although, instead, on the other hand, conversely, however, in contrast, on the other hand.

A third type of context clue is the example, when the author gives us specific instances, cases, or illustrations to clarify a word’s meaning. Common words and phrases that indicate examples include for instance, for example, to illustrate, and such as.

Also, authors may use a colon to introduce a series of examples.

Movies are often of different genres: romance, drama, action, gore, and sci-fi, to name a few.

Idioms such as “raining cats and dogs” and “spill the beans” often confuse people who are just learning English.

Finally, effective readers use their own personal context when reading; they connect what they’re reading to their previous knowledge on the subject and make logical inferences—they draw conclusions—based on what they know as they read.

D. Denotation and Connotation

A word’s denotation is its explicit dictionary meaning—what it stands for without any emotional associations.

A word’s connotation is the emotional, social, political associations it has in addition to its denotative meaning.

For example, assertive, aggressive, and pushy, although all related, have somewhat different denotations and connotations. Most writing require a combination of connotative and denotative language.

How do denotation and connotation fit in with reading comprehension? Sometimes while we are interpreting context clues to understand what we’re reading, we can also determine if a given word has positive, negative, or neutral connotations. On occasion, just knowing that a word has positive or negative connotations enables us to keep reading with sufficient comprehension, and we don’t have to stop and look up every single unknown word.

E. Vocabulary Study Using Word Parts

Learning word parts such as roots (which carry the word’s main meaning), prefixes (which come in front of the root), and suffixes (which come after the root) can expand and broaden our vocabulary.

Many of the words you encounter in college are based on Latin and Greek roots. For example, biology contains the Greek root bio-, meaning “life,” and the suffix –ology, meaning “the study of.”

Root: A root is a word from which other words are formed. For example, manufacture and manual both come from the Latin root manu, meaning “hand.”

Prefix: A letter or group of letters placed at the beginning of a word that change its meaning. Prefixes are not words and cannot be used alone in a sentence. Adding the prefix sur, which means “above” or “over” to real gives us surreal, meaning “unreal” or “fantastic.”

Suffix: A group of letters placed at the end of a word. A suffix often changes a word from word class to another. For example, if we add the suffix –able to the word like, like (a verb) becomes likeable (an adjective).

Here is a list of common Latin and Greek roots, prefixes, and suffixes to help you learn new words through recognizing these parts.

Common root words and meanings

| Latin Roots | Meanings | Examples |

| amare | to love | amiable |

| annus | year | annual |

| aduire | to hear | audible |

| capere | to take | capture |

| caput | head | capital |

| dict | to say | diction |

| duc, ductum | to lead | aqueduct |

| facere, factum | to make, to do | factory |

| loqui, loq | to speak | eloquent |

| lucere | to light | translucent |

| manu | hand | manuscript |

| medius | middle | mediate |

| mittere, miss | to send | admit, mission |

| omni | all | omnipotent |

| port | to carry | portable |

| scrib, script | to write | scribble |

| sent | to feel | sense |

| spec | to look | inspect |

| spir | to breathe | expire |

| verb | word | verbiage, verbal |

Prefixes indicating number

| Prefix | Meaning | Example |

| uni | one | unity |

| bi | two | bimonthly |

| duo | two | duet |

| tri | three | triangle |

| quadri | four | quadriceps |

| tetra | four | tetrahedron |

| quint | five | quintuplets |

| pent | five | pentagon |

| multi | many | multilingual |

| mono | one | monotonous |

| poly | many | polysyllabic |

Prefixes indicating space and sequence

| Prefix | Meaning | Example |

| ante | before | antebellum |

| circum | around | circumscribe |

| con | together, with | congregation |

| ex | out, from | exhale |

| in | in, into | inhale |

| intra | between | intramural |

| intro | within | introspection |

| macro | large | macroeconomics |

| micro | small | microscope |

| mini | small | miniature |

| omni | all | omnivore |

| post | after | postdate |

| pre | before | prerequisite |

| re | back | revise |

| sub | under | subterranean |

| super | above | supernatural |

Prefixes indicating negation

| Prefix | Meaning | Example |

| anti | against | antibiotic |

| contra | against | contradict |

| counter | opposing | counterclockwise |

| dis | not | disregard |

| il, ir | not | illegitimate, irregular |

| in, im | not | immature, incapacity |

| mal | wrong, bad | malnourished |

| non | not | nonviolent |

| pseudo | false | pseudonym |

Verb Suffixes

| Suffix | Meaning | Example |

| -en | to cause | redden, cheapen |

| -ate | to cause to be | animate |

| -ify | to make or cause | fortify |

Adjective Suffixes

| Suffix | Meaning | Example |

| -ic | pertaining to | democratic |

| -ous, -ose | full of | verbose, fibrous |

| -ish | having qualities of | childish |

| -ize | to make | modernize |

| -ly | at specific intervals | quarterly |

| -ology | the study of | psychology, sociology |

F. Note-taking Strategies

A well-developed system for taking notes while you read has several advantages. First, it keeps you actively engaged with the material you’re reading. Second, it helps you monitor your understanding and notice when you’re not comprehending an author’s point or when you have questions. Finally, good notetaking skills help you identify important information that you can later review for a test.

If you highlight, make sure to include the author’s main point, major supporting details, and key terms. Mark about 20% of the reading. If you highlight too much information, you will end up reading more than necessary when you are reviewing the material.

When annotating (writing explanatory notes in the margins or between the lines of the text), develop a system of shorthand that works for you, and make sure that your system helps you differentiate among main ideas, major details, minor details, steps in a process, important terms and examples, your personal reactions, and any questions you may have about the material.

G. SQ3R and Cornell Notes

Two well-known systems for reading and note taking are SQ3R and Cornell

notes.

SQ3R is an acronym for its major steps: survey, question, read, recite, and review.

Survey

Before you read, survey the title, introduction, and conclusion, any headings, visuals (photos, maps, charts, illustrations) and their captions, and the summary.

Question

Turn the titles, headings, and subheadings into questions. Ask yourself what you already know about the subject. You may write these questions if helpful.

Read

Look for answers to the questions you raised and to questions at the end of sections or chapters, read difficult sections more slowly, reread any parts that aren’t clear, note words in bold or in italics, read captions under pictures and other graphics, and read one section at a time.

Recite

After you read a section, orally ask yourself questions about it and answer in your own words, take notes in your own words, summarize, and underline or highlight main points.

Review

After you finish reading a section, go back over the questions you’ve created and see if you can still answer them. If not, refresh your memory. Create a study sheet containing the main points of the reading selection, and periodically review it so you don’t have to cram for an exam.

SQ3R is an effective reading and note-taking strategy because it involves seeing, saying, hearing, and writing.

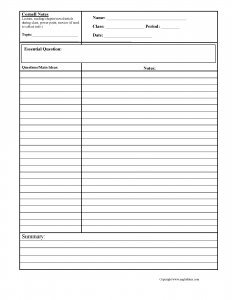

Cornell Notes is an effective note-taking strategy which is helpful both for lectures and for reading. First, divide your notebook into two columns: the smaller column on the left of the page for main ideas, important terms, and questions; the larger column on the right of the page for details, examples, and explanations. Reserve space at the bottom of the page to write a summary of the section, chapter, or page of notes.

One of the advantages of Cornell Notes is that they create built-in flashcards for review. When preparing for a test, you simply cover up the right-hand side of the page and quiz yourself about the main ideas. This is an effective and time-efficient study strategy.

Get a free printable Cornell Notes template like the one above at https://englishlinx.com/reading_comprehension/cornell-notes-reading-comprehension.html