How to Write an Essay

By Dr. Mike Barrett and Dustin Pascoe

Now that you know about the rhetorical situation and the kinds of essays you’ll be writing about in The Academy, it’s time to get to the essence of the communicative act in The Academy—how to write a good essay.

We’ll start again with classical rhetoric. When making a speech (much of classical rhetoric was a guide to effective speech-making), classical rhetoricians thought that the orator needed to go through five stages: Invention, Arrangement, Style, Memory, Delivery. Each of these stages can be adapted to the more contemporary rhetoric of writing.

The word “Invention” comes from the Latin word “invenire,” which means “to come upon.” For the classical rhetoricians, speech making began with the orator generating material to use in his or her speech. Using a deep, contemplative imagination, the orator first gathers the content, the substance of the speech. Then the orator organizes that material according to an Arrangement that will have the most profound effect on the audience. Once that material is generated and arranged, the orator matches the Style to the material and audience. Style includes metaphoric language, diction, allusions; in other words, the orator chooses a manner of speaking that will be the most persuasive. Consider it this way: A professor wouldn’t use the same style of speaking to a Freshman Philosophy class as she would to a seminar with doctoral students.

In the Memory stage, the orator memorizes the speech for fluent delivery. When reading accounts of classic and medieval rhetoric, the memory stage is often described as being in deep meditation; it seemed to be a contemplative state of preparation. Orators used many mnemonic devices in order to commit to memory prodigious speeches, and this in turn helped to develop their imagination.

The Delivery stage is when the orator would present the speech to the audience, using the appropriate modulation in tone and volume. The delivery stage included hand and facial gestures as well.

For writing an essay using contemporary rhetoric, the five offices of classical rhetoric have been condensed into three recursive stages: Invention, Drafting, and Revision.

A. Invention

Invention is the first critical stage in the writing process. In this stage, you study your writing assignment carefully (in The Academy, many rhetorical situations are assigned to you) in order to discover what you are being asked to write. If the assignment requires research (more about those kinds of rhetorical situations later), then you should use the invention stage to narrow down your research focus.

There are many ways to generate ideas to write about in the invention stage. Here are a handful of the most commonly used techniques.

Freewriting

Freewriting is when you set yourself a time limit, say five minutes or so, provide yourself a prompt, and then write whatever comes to your mind about that prompt. For example, let’s say that your assignment was to write an essay about whether or not cell phones should be banned from classrooms. Your initial prompt might be something like: Cell phones are a hazard in class because…

What follows would be whatever comes to your mind based on that prompt.

The purpose of freewriting is to unlock your brain and get yourself, without second-guessing or procrastination, to write. Writing takes commitment and is hard work—it takes persistence. Freewriting is one simple way to generate material.

Looping

Looping is a modified version of freewriting. One thing you’ll discover quickly with freewriting is that the mind can very quickly move far afield from the original prompt. Looping is one way to avoid that wandering. When you practice looping, you freewrite for a brief period, then you look over the material you’ve generated. You take an idea from the first freewriting session and use that as a prompt for your next freewriting. Then you take an idea from the second freewrite and use that as a prompt for your next freewrite. You can do this as many times as is effective.

Notice what happens in looping—you are focusing on promising ideas and then developing those ideas. As mentioned earlier, freewriting is effective for getting the juices flowing, but it has a tendency to drift; looping keeps the writer on task.

The Reporter’s Questions

No matter what you are writing about, asking the reporter’s questions—who, what, when, where, why, and how—are an effective

place to begin. Let’s try them out with the cell phone issue.

Who: Students in class, and teachers

What: Cell phones and all their apps

When: During class

Where: In The Academy

Why: Social conditioning, inattentiveness, cultural programming, robot conspiracy

How: Institutional ban, let students text, keep students busy so they can’t be distracted.

You’ll notice in the example above that Why and How lead to multiple possibilities. Where there are multiple answers, there are multiple opportunities for paper topics.

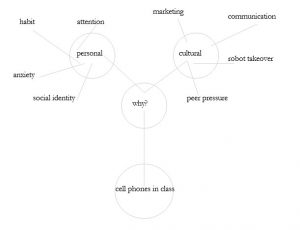

Clustering

Clustering, or idea mapping, is a visual way to generate ideas. You make the main idea a hub, and then ancillary ideas as spokes from the hub. Each ancillary idea, though, can be its own mini-hub with its own spokes. Using clustering as a way to invent material also helps you begin to develop and organize the material you generate.

As you can see, as the ideas are developed, they are organized into subcategories. In this example, the first ideas developed are the reasons why students look at cell phones in class. Two major reasons emerged—personal reasons and cultural reasons. Note that each of the individual reasons under each category can also serve as hubs for further development.

Listing

Listing is the invention technique that I frequently use. After I have finished research, I list all the things I want to say. Then I cluster that list, putting ideas in relation to each other in order to produce a suitable arrangement for the material.

There are many other techniques for invention. The ones included here have been used successfully by students. You MUST begin with the invention stage. In The Academy, it is nearly impossible to sit at the computer and write an essay from the top of the page and the top of your head. You must have a roadmap before you begin the drafting stage. Recall classical rhetoric—immediately following the invention stage is the arrangement stage. For our purposes, invention ends in arrangement. Many people use outlines to arrange their material. I use lists or idea maps. Whatever you choose to use, YOU MUST HAVE A PLAN BEFORE YOU START TO DRAFT. In the following section, I’ll describe a simple and effective way to invent and arrange your essays before drafting.

1. A Simple and Efficient Plan for Arrangement

I learned this way to invent and arrange during a stint in graduate school as a commercial writer. I would be hired by businesses to ghostwrite articles for them to be published in their trade journals. At first, I had a difficult time writing in a style that was suitable for magazines. The problem was that I was used to the long paragraphs of academic writing and those paragraphs were out of place for the breezy writing style of magazines.

What I did to improve my drafts is something that film directors do all the time—they envision, at all times, what the scene they are filming will look like when it is on the screen in the movie theater. In other words, they keep a constant focus on the final product, even when in the preliminary stages. For me, that meant setting the margins of my word processing file exactly as wide as the margin for each column of prose in the magazine. In this way, the number of characters per line as I drafted, would be the exact number of characters per line in the final product. In that way, as I wrote, I would see what my article would look like to the reading public.

a. Paragraphs

How does this work for you when writing an essay for The Academy? Before you learn this technique we need to discuss paragraphs.

First, understand that paragraphs are the basic building blocks of your essay. They are the prime movers of your purpose no matter what that purpose is. Secondly, you must understand that, typically, paragraphs develop one main idea. When you were in secondary school, you probably learned about topic sentences. A topic sentence is to a paragraph what a thesis is for the essay— it succinctly states what the paragraph is going to develop. For example (topic sentence in italics):

As you can see, the topic sentence makes a promise (as theses do) that the rest of the paragraph will fulfill.

You should note that in The Academy, topic sentences are not a requirement. An essay that includes a topic sentence for every paragraph will read as if it were written by a machine. Style dictates that the presentation of the material matches the purpose and, unless the purpose demands the rigid construction of topic sentences for each paragraph (technical manuals for example), do not think you need to construct your essay that way. What is not negotiable, though, is that each paragraph needs to represent one main, developed idea.

b. Using Key Words to Arrange

One way to check if your paragraph does indeed represent one main idea is to try to reduce that idea to a key word and key phrase. (This technique is discussed in Joseph Williams’s book, Style: Toward Clarity and Grace). Indeed, this works in reverse as well; in the invention stage, reduce each idea you will be discussing in the essay into a key word and phrase.

Once you are used to thinking of an essay in terms of its building blocks, paragraphs, you will be amazed, if you keep the final product in mind, how easy it is to complete the invention and arrangement stage. For example, say that you are asked to write a five-page essay on the causes of the first Iraqi War. Generally speaking, there are two or three paragraphs per page of an essay. Therefore, the sum total of paragraphs you will need for the essay is approximately 12-15 paragraphs in all. Take away one paragraph for the introduction and conclusion (special paragraphs we’ll discuss in a bit). That leaves approximately 10-12 paragraphs left for the body. Now before you start the invention stage, keep this number in mind. As you do your research, you know that you’ll have to generate 10-12 ideas relating to the causes of Operation Desert Storm. That sounds do-able, especially considering that one idea may have two aspects and therefore two paragraphs.

In addition, using this technique—keeping an eye on the final product throughout—helps you in the arrangement stage. After you do your research and isolate related ideas to discuss, you can arrange those key words or phrases in the order that you will treat them in your essay. So you have an arrangement scheme for the drafting stage. This technique makes the process of writing efficient because throughout you are working toward a final product that you have considered and kept in mind every step of the way. No preliminary work is wasted.

Pascoe’s Primer—Arrangement

Strategic Organization

“Strategic Organization” means arranging the information in the Middle for maximum clarity and effect. It may be that when drafting no thought was given to the order of the main points, or it has become apparent that the main points do not seem to have the internal coherence they need. If so, there are several ways to arrange main points. The writer should choose the method most rhetorically sensible for the task at hand.

-

- Chronological: Like it sounds, this is an order based on time. It would be possible, of course, to start in the past and work forward or vice versa, but it should be sequenced.

- Spatial: Based on physical space, this strategy moves north to south, top to bottom, front to back, etc. Clearly, it would work best when a tangible object or area (like a car or the state of Missouri) are being discussed.

- Problem-Solution: This strategy is best for persuasive works or studies of experiments. It can be slightly varied as problem-cause-solution.

- Topical: This is the “catch-all” category as it includes any organization that doesn’t fit into one of the above strategies. Topical organization takes main points that are unrelated to each other and imposes a structure on them (For instance, a topical paper on the Beatles would have main ideas like their sense of fashion, the lyrics of their songs, and how Yoko broke them up). Topical is probably the most widely useful.

2. Introductions and Conclusions

What you learned in elementary school that an essay has three parts—an introduction, body, and conclusion—still applies to writing essays in The Academy. Introductions and conclusions serve a special purpose in the essay different from the body.

The introduction to your essay should grab your reader’s attention and make them want to read more. It should give your reader an idea of what’s ahead in the essay, and, most importantly, it ought to indicate what the purpose of the essay is. Not all essays require a thesis in the introduction. Why? Because we have defined a thesis as the claim an argument is trying to prove and not all essays have as their purpose to prove a claim. For example, self-expressive essays do not require a thesis statement but remember, all essays should make their purpose known early in the essay, preferably in the introduction.

If you look up, “How to write a conclusion,” I’m sure that you would generate a list of specific strategies such as: “re-state the thesis,” or “ask a question,” or “call your readers to action.” These can be effective strategies but their specificity ignores the general sense of what the conclusion ought to accomplish.

Pascoe’s Primer—Introductions

Here, the writer may accomplish five things:

- Get the reader’s attention [called exigency]

- Explain what is happening [lab report, biography of Civil War general, analysis of poem, etc.] (Note: Don’t literally say “in this essay, I will discuss …”)

- Provide any background the reader will need to understand [key terms, concepts]

- Preview the body/main ideas of the essay [a thesis statement]

- Provide a transition into the body.

My theory of conclusions is as follows: When you write an essay, you are creating a home-made intellectual world for your reader to reside in while they read your words. Your conclusion, then, should be the place in your essay where you give something from the essay to your readers to take with them when they leave your world and re-enter their own.

With this principle of conclusion, you may want to re-state the thesis, ask a question, or call to action, but that is not all. The conclusion is not a tactic but a strategy and should answer the question: What do you want to leave your readers from your essay? Think of the conclusion as the essay’s gift to the reader for reading.

B. Drafting

Once you have your scheme for arrangement, it is time to draft your essay. This stage is where difficulties often arise for a simple reason—writing takes effort!

Any number of writing manuals will give you advice on the best way to approach drafting—from the time of day to the locale where you do your writing. That is all fine and maybe even helpful, but the truth is you have to sit down and concentrate in following your arrangement. There are no shortcuts and numerous diversions. In the time between I wrote the title “Drafting” and this sentence, I’ve checked my email, petted my dog, and looked to see if the oven has reached its preheated temperature. That’s a lot of diversion for only five sentences.

Pascoe’s Primer—Drafting

Here in stage two, it is time to begin putting things together in sentences and possibly paragraphs. Like in the Idea Generating stage, a student should not reject an idea here until it has been tried. This step is essentially creative.

- Main ideas: The writer should decide on the most important aspects of information to be conveyed. Ideally, there should be between two and five main ideas (although a single main idea is possible). Any more than five and – depending on the length of the whole – it becomes difficult for the reader to keep them clearly in mind.

- Outlining: While not every writer, or every project, needs an outline, it is a helpful tool in the drafting process because it allows the writer to turn simple ideas or phrases into complete sentences and sentences into paragraphs. It also helps prevent repetition or accidentally leaving something out. Again, for the visually-minded, it looks like a map.

- Beginning, Middle and End: All complete writings should have distinct beginnings, middles and ends, and this is the point at which to begin thinking about how to construct them. While there is no correspondence to paragraphs here, they should be separate from one another. For assignments that cannot reasonably include all three (very short abstracts or reports, for instance) the Middle is the bit that contains all the necessary information.

Yet here I sit, again, tending to the draft of this handbook. I have a mantra I tell my students, “one word in front of the other.” That is the only way to write. If you are always thinking about the page length or are counting words constantly to find out how much more you have to say (not a good idea) you’ll find it very difficult to complete a draft. Concentrate on the word in front of you, then the next word, and the next until you have a sentence. Keep at it until you have a paragraph. With concentration and effort, you’ll discover that you have finished the … hold on … I’ve got to check the oven.

C. Revision

Before we discuss the stage of revision in the writing process, let’s make one critical distinction—writing is not a linear process (1,2,3 and done)—but is a recursive process. A recursive process is a process that can be broken down into sub-processes that may loop over each other. In programming, think of a routine that is constructed from a series of sub-routines. To illustrate with writing: imagine you are in the drafting stage and you write, “we ran from the cops.” You stop and decide that “ran” is not a descriptive enough verb, so you think of a better verb and come up with “fled.” You then delete “ran” and replace it with “fled.” Can you detect the sub-routines here? You are drafting, then inventing, then revising, then return to drafting.

Two resources that can help you revise your essay are your instructor and the tutors in MACC’s Library and Academic Resource Centers. If you have a draft of your essay finished before it’s due, bring it to your instructor during his or her office hours and have them give you directions for revision. For sure, your instructor knows what they are looking for from you. MACC’s LARCs are staffed with tutors skilled in various subject areas. Go over your essays with tutors in order to develop a plan for revision. Another set of eyes is always helpful when looking over written work.

When revising your essay, it is commonplace to say that you start with the macro issues of purpose, organization, paragraphing, and finish with the micro issues like spelling and punctuation (i.e..proofreading). Revision is more than proofreading — it is a re-visioning of all aspects of your essay.

There are a number of effective strategies for revising your essay, but I’ll tie our strategy to MACC’s global communications rubric—which is how we as an institution check to see whether or not our students are generating successful writing. The rubric is organized according to outcomes. Note that some of these outcomes apply only to argumentative essays.

The first outcome is general and focuses on effectively communicating your purpose in language that is appropriate to The Academy.

Outcome IA: The student will demonstrate effective written and/or oral communication considering audience and situation through invention, arrangement, drafting, revision, and delivery.

- Is the essay’s purpose clear, complex, and explicitly expressed?

- Is the text unified – each element effectively serving the purpose?

- Is the text appropriately directed to an academic audience?

- Is the language concrete and specific, as opposed to general and abstract?

The second outcome applies to argumentative essays and focuses on the effectiveness of the logic used in constructing the argument.

Outcome IB: The student will construct logical and ethical arguments with evidence to support the conclusions.

- Does the text contain an explicit, concisely expressed, and original claim?

- Is the claim buttressed by effective and varied support?

- Are the warrants, stated or assumed, reasonable and free of fallacies?

The third outcome applies to the writing adhering to grammatical, usage, and stylistic principles.

Outcome IC: The student will conform to the rules of Standard English.

- Does the text contain standard academic grammar?

- Is the spelling correct?

- Is the punctuation appropriate?

The fourth outcome concerns the effective synthesis of the essay’s material.

Outcome ID: The student will analyze, synthesize, and evaluate a variety of course material and points of view.

- Does the text include a variety of appropriate material?

- Has that material been appropriately analyzed?

- Has that analysis led to a synthesis directly related to the essay’s purpose?

The fifth outcome concerns the ethos of the writer and how well the protocols of citation have been followed.

Outcome IE: The student will accept academic responsibility for all work regarding issues of copyright, plagiarism, and fairness.

- Is the text free of plagiarism?

- Is the text free of copyright violations?

- Are the sources properly cited in the appropriate citation format?

- Is there a citation page?

1. Final Thoughts on Revision

In a poem I once wrote, I was thinking about the relationship between writing and our moral life. When we err morally, we can determine to do better next time, but we cannot change the past—our actions are inscribed in the book of time. When we write, though, our texts can accommodate as much time as we have to put into them. In addition, if we make a mistake, we can fix it we can go back in time. The line I wrote for my poem was, “Revision means forgiven.” Think about your text as an opportunity to create the most complete ethical act. And if you make a mistake, that’s ok, you can fix it: revision means forgiven.

2. Delivery

Do you want to know one key element in establishing ethos as a writer? Turn the assignment in on time in the manner the instructor requires. That may be in a Dropbox set up in the Learning Management System, or in hard copy to be handed in during class. If the instructor requests that the essay be handed in hard copy, or submitted through your LMS, do not email it. Follow the instructions.

If there are special instructions for delivery, abide by those. MLA format f0or essays without ancillary material (like appendices or works cited pages) do not require a cover sheet and are to be formatted as illustrated below (not to scale):

3. Sample Essay Format

Double spaced, 1-inch margins

header 1 inch from the top, title centered

Barrett 1

Mike Barrett

Professor Pellopi

LAL101

24 Feb. 2022

Neoliberalism & Community Colleges

(Indent first line of paragraphs 1/2 inch — this usually done by hitting the tab key once on your keyboard) Cecilii libellum,

quem de Sublimitate composuit, perpendentibus nobis (ut scis) una, Posthumi Terentiane charissime, humilioris stili esse visus

est quam postularet argumenti materia, et [3/5] praecipuas res minime attingere, neque multum utilitatis (quam maxime debet

scriptor petere) legentibus afferre. Deinde cum in omni artis alicujus tractatione duae res requiruntur, (prior quidem, ut osten

das quid sit subjectum; secunda vero quoad ordinem secunda, at quoad vim potior, ut ostendas quomodo et quibus rationibus

hoc ipsum sit a nobis acquirendum), nihilominus Cecilius, quid sit Sublimitas, innumeris exemplis.

E. Mackey’s Maxim: Answering the “So, What?” Question

By Jill Mackey

One way to think of the concluding paragraph of an essay written for a course taken in The Academy is to consider it as your opportunity to answer what I call the “So, what?” question. The answer to this question is a brief explanation of why the reader has spent the better part of half an hour (or longer!) reading your writing. Think of the answers to the “So, what?” question in terms of answers to other questions: What is the pay-off for the reader? What is the significance of the point you are trying to make? In the words of Dr. Barrett, what is “the essay’s gift to the reader for reading”? This discussion can be as brief as a sentence or two (or longer). It should be embedded gracefully within the concluding paragraph. It may or may not begin the concluding paragraph, but however you construct your concluding paragraph, the reader should be able to tell, in addition to looking, by your words and your tone that you are coming to the end of your essay. Examine the following concluding paragraph:

The law is a natural and vital part of human society. Everyone, from beggars to kings, makes use of it or is affected by it. When the law is functioning as it should, each addition to it will help the whole of society, not just a select group who will exploit it for their own ends. It is designed for the benefit of someone, somewhere, and even those who openly defy it are influenced and protected, as seen in the United States where even the worst criminals are promised a speedy trial and protection from cruel and unusual punishment. That protection, that promise that it will do everything in its power to ensure a safe life for those under it, is what gives the law its jurisdiction.

–Thomas Stacey

You can probably infer from the opening sentence that this paragraph is from an essay on the function of law within our society. Notice how the writer seems to summarize the points made in the essay by each succeeding sentence— until, that is, the final sentence. Here is this writer’s answer to the “So, what?” question. His answer affirms the need for laws in a just society on the principle that we all want to be safe. No, it’s not rocket science; it’s more important. It’s the bedrock on which any just society is based. The fact that this student arrived at such a seemingly simple observation is music to a professor’s ears.