Ingarihi hei reo

Do not seek to follow in the footsteps of the wise. Seek what they sought.

– Matsuo Basho

te ao Māori principles

There are five key principals that we as an English Department consider important as part of a holistic study at school. Please read through these and know that we will come back to them as we begin looking at texts.

- Kaitiakitanga: Guardianship of natural resources and elements of sustainability

- Rangatiratanga: Leadership, authority, Mana, empowerment, Respect

- Manaakitanga: The process of showing respect, generosity and care for others.

- Whanaungatanga: A relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides people with a sense of belonging.

- Tikanga: The customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in the social context.

Key Terms

|

the imparting or exchanging of information by speaking, writing, or using some other medium.

|

|

intended to communicate something that is not directly expressed.

|

|

the arrangement of and relations between the parts or elements of something complex. |

|

relating to or capable of production or reproduction. |

|

(of a process or system) characterized by constant change, activity, or progress.

|

Learning Objectives

- Identify your own language

- Articulate the difference between literature and language

- Introduce the course

Exercises

Spelling

| rating | Buddhism | quantity | socialist | justify | seal |

| engineer | phase | necessarily | parishioner | opponent | exception |

| accusation | immigration | examination | visible | essentially | mount |

| competitor | construction | imply | associate | urban | comfortable |

| inspector | explanation | panel | literary | dessert | universe |

[h5p id=”1″]

Pangram

Remember, to become faster at writing, you should practise writing out the following phrase as many times as possible for 5 minutes.

- A wizard’s job is to vex chumps quickly in fog.

English as a Language

Ingarihi hei reo

Consider the concept of English as a language. A language is a system of communication which consists of a set of sounds and written symbols which are used by the people of a particular country or region for talking or writing.

We need to think about English class at school as a way to be better at communicating with others.

Words are just letters. Yet we add so much value to each one. Some words have the power to hurt, others have the power to heal.

The aim of this year is to provide you with the fundamental elements of English to help you prepare for specialist study at the higher levels.

Exercises

Consider the following styles of language that you use in your daily communication. Put a (F) when you think there is a formal style of communication, a (I) when you think there is an informal style of communication, and a (?) if you aren’t sure.

- A letter to the local mayor.

- An email to your friend in Australia.

- A text message to your dad to pick you up at a certain time.

- An instant message (DM or Facebook style)

- An email to your teacher.

- An essay about something you had studied in class.

- A magazine article on a celebrity.

- A speech on the importance of recycling.

The idea of code switching is looking at the situation and working out how best to speak. A big part of this year is recognising what is required in order to make the most of every situation you come across.

In dealing with other people, there is a psychological term that is called the Law of Reciprocity which says that we react to the way that others interact with us. This is a very strong instinct. Sometimes people can copy the level of formality, or even someone’s accent a little, to make them feel more comfortable.

Think about your conversations with your caregivers after school when they ask how your day was. If you give little in response then that is likely to make them feel upset or hurt because you have not adhered to the law of reciprocity. If you respond using sentences then you have met the expectation and things will go more smoothly.

Words Words Words

Think about the word ‘set’. According to the Guinness World Records, the word ‘set’ has the most definitions attached to it. How many can you come up with, without using your dictionary.

We can all recognise that language is important. It creates music, starts wars, and generally makes the world go round. It is a vital skill that we, as students, can learn over the course of our high school career.

Consider the following ideas and consider how language works for you.

1. Language Is Communicative

Communicative by definition is a willingness to dispense information. The ancient Roman society preserved records and instructed their children and students in the form and vocabulary, the lexicon of their language. Because of its communicative nature, that ancient language, Latin, existed for centuries creating generational culture which sustained that society, and continues to provide the rudiments for medical and scientific language.

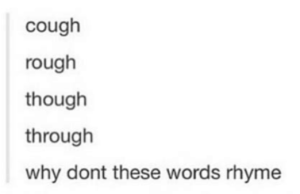

2. Language Is Arbitrary in Nature

One word describing an object may very well be another—such as the word door could as easily have been assigned to a window. Language is based on random choices by groups of people (nations, even) to communicate needs and wants, a collective system for commerce and shared understanding.

3. Language Is Structured

There is a pattern of organisation within language (words go with other words and eventually make sentences) that takes an identifiable shape. The patterns must be familiar enough to be identifiable to all other users of that language. Language has basic building blocks that set it aside from other forms of communication.

4. Language Is Generative

Language constantly creates new words, new phrases, new structures—it generates more of itself. It is comparable to a living thing that reproduces, changes, and even dies. Even though Latin is a dead tongue, those who use it keep it alive or generative by speaking and writing it.

5. Language Is Dynamic

Language experiences change and development as time passes, which can cause some questions in the mind of some who seek to preserve the integrity of certain cultural aspects surrounding a language. But for this work, dynamic is a decent gauge for describing language. Dynamic in this cause means that language has the ability to evolve and never repeat the same phrase with the same meaning in the same way without doing so on purpose.

Exercises

Watch the following piece from Stephen Fry and consider the following:

- How does language show who you are?

- Do you agree with Stephen Fry?

- Is language something you have thought about when you think about yourself?

Language Perspective

Culture does influence a person’s view of the world—shaping our ideas and behavior—meaning that a person may respond differently depending on how the words leave our mouths because of the way we have to hold our tongue to say those words.

We all have a view of the world. In a pepeha (an introduction in Māori) the speaker will first acknowledge their maunga, their mountain. This does two things, it shows the listener where they are from the world as defined by the geographical feature of a mountain. At Macleans we would acknowledge the mountain of Ōhuiarangi (or Pigeon Mountain) in our pepeha.

So location is the first reason why, it tells the listener what part of the world we come from.

But it also does something else: the second reason why Māori say the mountain they are from is because it demonstrates that they may have a different perspective to the listener. For example, a speaker who comes from the coast will see a lot of sea from the top of their mountain, they may therefore think of the sea as being of great value to their life. It provides food, adventure and a daily part of their lives. A person who has Mt Ruapehu as their maunga will not have the same view from the top of their mountain. In fact, that is a mountain covered in snow and the nearest body of water is the great depths of Taupō, a lake. They have a different perspective on the world.

Consider your perspective.

You will have a completely different perspective on things to the person sitting next to you, to your parents or caregivers, to your teacher, to your friends. Each person has their own perspective based upon their age, history, associations etc etc.

Whenever you are in a conversation with someone else, listen to them. You carry your perspectives with you. So do they. It is only through language that we are able to find the ability to compromise and work collaboratively.

An extract from The Tomo by Mary-Anne Scott

The family meeting was scheduled for late afternoon. Mum wouldn’t be drawn on what was going to be discussed no matter how many times Phil questioned her. ‘It’s not more bad news about Dad, is it?’ He followed her out to the clothes line. ‘We’re staying home for Christmas, right?’

Mum brought the washing in, her fingers moving over the pegs like a pecking bird. She looked past Phil to nod at the scrubby, dry lawn. ‘Pick up the Blue poo, will you? I shouldn’t have to ask every day.’

‘So, it’s bad news. You won’t say because it’s terrible.’ Phil picked up the scoop and Blue must have heard the metal scrape from inside the house because she bounded out to dance around him as he cleaned up her messes. He couldn’t help laughing. ‘This is not normal dog behaviour.’

Mum paused to watch, the washing basket tucked under her arm. Blue danced on the grass, lifting her paws as if the grass was hot. ‘Normal is not a word I’d use to describe that dog.’ She walked inside, saying as she went. ‘I can hear Skip’s ute. Let’s get this meeting started.’

Dad was in his wheel chair in the front room and Blue ran to take up her seat at his side. She was Dad’s dog, his heading dog slash pet, slash devoted buddy. Dad had his eyes shut but he reached out to stroke Blue’s silky ears. ‘Hello, my girl,’ and Blue licked his hand. They sat quietly then, the only sound being the small fan which clattered on the sideboard, working hard to provide a breeze.

Phil thought Dad looked thinner and sicker today — a half-a-dad. ‘He’s battling cancer,’ people said, but that implied a fight when it seemed to Phil that Dad was being consumed by cancer. It had started one day in his prostate and within six months it had crept to his lymph nodes and into every aspect of the family’s lives. Phil imagined the cancer like the rust in their car — appearing one day beside the exhaust pipe and then eating at three of the doors. The Davidsons’ car was old and clapped-out so it was probably due to get some rust, but Dad was not exactly old at forty-one, and he had been fit. It made no sense.

There were six in the Davidson family — including Blue — and the whole family always included Blue. Dad used to be a farm manager but when he became sick, he took what work he could, as a casual. He’d shifted around the district following work opportunities, covering for farmers who needed a break or as an extra pair of hands, until in an unlucky twist, it was now Dad who needed the break.

‘Help yourselves,’ Mum said as she carried in a plate of fallen-apart sushi rolls. She’d been given them free at the sushi bar in town where she worked.

‘No, thanks,’ Phil said.

Dad shook his head.

Oliver asked, ‘Why can’t we have biscuits?’

Skip wandered in, spinning his car keys around his finger. He was the eldest of the three boys, at seventeen and a half. He had a full driver’s licence — and that mattered to Skip. ‘Some idiot towing a trailer held me up,’ Skip said. Phil thought people were always getting in Skip’s way. Dad called Skip ‘my right-hand man’, he’d always called him that even when Skip had been so young he would’ve been a ‘right-hand toddler’. He’d left school a year ago and was working on farms like Dad, but as a general hand. He picked up four pieces of sushi and trailed bits of rice as he walked to a chair.

‘Hand Skip a plate, will you, Phil?’

Phil passed a side plate to Skip who mumbled around his mouthful, ‘What’s this meeting all about? What’s up with you, Smif?’

Phil’s nickname, Smif, started when the PE teacher had called Phil a small fifteen when she was picking teams for inter-house competitions last winter. Skip heard about it, shortened the name to Smif and it caught on. Phil also got ‘four-eyes’, but Smif pissed him off more. ‘Nothing’s up,’ Phil said.

‘Why can’t I have a biscuit?’ Oliver asked. He leaned over the plate of sushi and picked out the salmon.

‘Niney and whiney, you are. Get your mitts off,’ Skip said.

Mum sat down beside Dad, her legs twisted like a cheese straw, her face frowning, as she ran through her list of things to be discussed. She said, ‘Let’s get started. Thanks for being here,’ which was really just a thanks to Skip as everyone else was already home. She tapped her pen on her page. ‘Dad’s been accepted on a treatment programme. It’s a trial but we’re very hopeful. And grateful,’ she added. ‘But it means we have to be in Auckland from the twenty-first of December for the initial tests and to get him started — if he’s suitable. Unfortunately, Christmas will be side-lined this year.’ Oliver let out a howl and Mum said, ‘Give me a chance to speak, Oliver. You’ll be staying at my Aunt Lily’s. I’m sure you’ll have a special Christmas with her.’

‘Noooooo,’ Oliver said. ‘Why can’t I stay—?’

‘She loves sweets, remember,’ Mum said, and they all watched Oliver weigh up the good and the bad of his situation. Mum said, ‘You’ll have a wonderful time. She’s looking forward to having you.’

Phil doubted that. He’d noticed Aunt Lily frown when Oliver ran through his complaints posed as questions. ‘How come there’s only crumbs left in the Weetbix? Why do all my socks have loose tops? Why can’t I watch TV? Why is our sushi always broken?’

‘Moving on,’ Mum said and she pointed her pen at Skip. ‘You’ll be covering at McArdle’s for Dad so nothing really changes except that we’d like you to collect Oliver each Sunday and spend the day with him. Aunt Lily has church services and routines she wants to keep up.’

‘Each Sunday? That’s over an hour’s drive from McArdle’s into the middle of Gisborne. It’s my only day off.’

‘It’s probably only two Sundays, Skip, and we’re all making sacrifices so Dad can take this opportunity.’

Phil found it hard to breathe. He wondered what his sacrifice would be. Mum turned to him, next. ‘I’ve managed to find you a job for this time Phil.’ She spoke softly but each word boomed in his head. ‘Years ago, when I was pregnant with you, I worked as a receptionist in a health clinic in the centre of town, and a woman, Penny Tiopera, was the physio there. She was pregnant at the same time and we’ve seen each other occasionally. She was getting sushi the other day — one thing led to another — and she’s offered to help.’

Phil felt his face heat up and he reached down to adjust his shoelaces. The spider-web design was his best effort yet, and just staring at the intricate knot helped level his heart beats. Mum continued, ‘Penny Tiopera and her husband Chopper Harris live on the back road between Tiniroto and Frasertown. They manage a big station there for a Māori Trust and she said you could help Chopper while she and her daughter are away over Christmas and then through mustering when they’re back around the twenty-seventh.’

Skip had already whipped his phone out. He searched and scrolled then expanded on a photo. ‘What’s the daughter’s name?’ He peered closely at his screen. ‘Emara Tiopera?’

Mum frowned at Skip. ‘Yes, her name is Emara but I don’t think it’s a good idea to—’

‘She looks like she’s into horses, because there’s a horse in nearly every photo.’

‘Anyway,’ Mum said, trying to wrestle back control of her meeting, ‘this is a wonderful opportunity. As I said, they’ll be mustering over January.’

‘The girl looks too cool for you, Smif, so don’t be thinking you’ll have a girlfriend.’ He grinned around the room to see if anyone appreciated his joke.

‘A girlfriend!’ Oliver’s eyes were wide.

‘I’m not going,’ Phil said. ‘So, you can all shut it.’

Mum glared at Skip and muttered, ‘Most unhelpful.’

Skip shrugged. ‘I was only having a laugh.’ Mum gave him a very long stare so Skip said, ‘I know where this station is. It sits under Mt Whakapūnake. It’s mint out there, Smif. You’ll like it.’

‘This could be a great chance for you, Phil,’ Dad said. His voice was croaky so he cleared his throat a bit. ‘I hope you’ll give it a go.’

‘Why can’t I stay home? I’ll mind the house and do the garden, every day. I’ll—’

‘The house is rented out,’ Dad said in a hoarse whisper.

‘People are desperate to rent holiday homes in Gisborne over Christmas. We’ve found a family who’ll pay decent money to stay until New Year,’ Mum said. ‘If the tests go well, we could be home by then but I’ve organised for you younger boys to be away a bit longer in case we’re not finished.’

No one spoke for a while. Phil imagined someone else in his room, his special space that was just a narrow sunporch off Skip’s bedroom. It clung to the rest of the house like a dinghy attached to a bigger boat. He loved his high iron bed, the eight rattly windows along the wall and even the sheets strung up for curtains, but most of all, how it looked out over the vege patch that Phil was looking after for Dad. Keeping the garden alive seemed crucial to keeping Dad alive. He didn’t feel able to mention the garden again, so he said, ‘I’ll find work here, in town somewhere or a petrol station. Why can’t I go with Oliver?’

‘Aunt Lily thinks she can only manage one of you,’ Mum said. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘Harden up, mate,’ Skip said. ‘This is a good chance to see how a big station runs. They’ll be getting sheep down into the yards for shearing, so you’ll get to ride the horses.’

Dad patted the stool beside him. ‘Come here, Phil.’

Phil felt exposed and trapped. Tears pricked the back of his eyes but he moved to sit next to Dad and Blue. ‘What?’

‘You’re a good boy.’

Phil nodded, although it didn’t feel like much of a compliment. The room was silent, even Blue tilted her head to listen. The white ruffle of fur around her neck fluttered in the fan breeze and her remarkable eyes bored into Phil. Dad dropped his hand on Blue’s head and said, ‘You can take my girl, Blue.’

There was an intake of breath from around the room. Blue turned to look at Dad as if to say, what’s this? But Dad’s eyes were on Phil so Blue looked that way again. She leaned in and Phil felt her nose press against his hand.

‘Me? I can take Blue?’ Phil wiped his eyes.

‘He doesn’t mean out to the station,’ Skip scoffed.

But Dad nodded. ‘I do mean that.’

‘No way,’ Skip cracked his knuckles and appealed to his mother. ‘If Blue isn’t here with Dad, then I should have her. I’m the oldest.’

Dad said firmly, ‘Phil can take Blue.’

Phil placed his clothes out in piles along the floor, then rechecked his list to be sure he had everything. Through the door he could see Skip’s gear strewn over his bed. Skip was lying on his clothes, eating an apple. Blue lay on Phil’s bed with her eyes shut, but her ears were up like antennae.

‘You’re gunna have to work hard out there,’ Skip called to Phil. ‘That Chopper guy isn’t going to be happy about being stuck with a fifteen-year-old.’

‘He’ll be pleased he’s got some help. Especially when he sees how good Blue is at heading.’

‘That’s the thing,’ Skip said. ‘Farmers have their routines and they’re too busy to have kids around. I’ve heard this Chopper guy is tough.’

Phil carried his list to the doorway. ‘Like what?’

‘Well, grumpy. Heaps of farmers are grumpy because there’s never enough time to do all the jobs and they think everyone is picking on them — which they are.’ Skip stopped chewing for a moment as he thought about something. ‘Don’t take Blue. Chopper will have his own dogs and he won’t want Blue getting in the way. You should definitely leave her.’

Blue lifted her head at the sound of her name. She swivelled her extraordinary eyes, one brown and one blue, from Phil to Skip, trying to understand the conversation. Her blue eye caught the light, making it gleam like a sapphire. ‘I’m taking her,’ Phil said. ‘She’d rather be with me.’ They both knew this was true. Blue adored Dad first, then Phil second and there was nothing Skip could do to change it.

‘You’d better take damn good care of her. If anything happens, you’ll have me to answer to.’

Blue sighed at Skip’s tone, curled back into a half-circle, but kept one eye open. Phil leaned in to check which eye was peeping and grinned at Skip. ‘She hates you. She’s giving you the brown eye.’

The morning Phil was due to leave, six days before Christmas, he woke up to find Oliver curled up on his bed in the very space Blue sometimes lay. ‘Whatcha’ doing?’ Phil mumbled, bleary with sleep.

‘I don’t want you to go and I don’t want to go to Aunt Lily’s.’

‘I know how you feel but we all have to do this. For Dad. This trial he’s on is gunna work and we’ll all be normal again.’ Phil dug his fingers into his palms. He propped himself up and Oliver passed him his glasses. Once they were on his face, Phil could think more clearly. ‘What would help you? Do you want to look after some of my stuff?’

Immediately, Oliver brightened. ‘Like what? Can I mind your money?’

‘Mum’s putting stuff like that into a locked cupboard but you can take care of Chase.’ Phil grabbed the police dog he should have grown out of from the rickety shelf above his bed. He chucked it at Oliver who hugged it close.

‘It’s fair, isn’t it? You’ve got Blue and I’ve got Chase. We’re sharing the load.’

Phil laughed at Oliver’s use of Mum’s expression. ‘Yeah, I guess we are.’ Phil plumped his pillow and lay back down. Despite having Blue for company, Phil’s load felt anything but shared that morning.

‘What else?’ Oliver, always on the hunt for an opportunity, looked around the room. ‘How about your book of knots?’

‘I’d better take that.’

‘But you already know every knot there is. I could be learning while you’re away and get as good as you,’ Oliver said.

Phil was good at knots. Skip said he was obsessed with knots which was quite possible as Phil knew he became fixated on things. This obsession had started when he’d been selecting a topic for his English speech. The school library had a small book on knots but it wasn’t enough and they had to list sources for their topic other than the internet. Mrs Kersten, the librarian, lent Phil a book from her house that explained the theories, categories, uses, components and most of all the strength and slippage of knots.

Phil borrowed the book most days in his lunchbreak until Mrs Kersten said, ‘Keep that book, Phil. It was just sitting on my shelf at home and what good is that when it could be read every day?’

The speech day came and went but the knot tying locked in as surely as the knots themselves. There was a symmetry to twisting the ropes; the ritual of right over left, or slide the loop under.

Phil sighed. ‘Alright, you can borrow my book. I probably won’t need it.’

Oliver grinned happily and bounced on the bed as he quoted the last line of Phil’s assessment speech. ‘You never know, a knot might be the difference between life and death.’

Taken from “https://www.ketebooks.co.nz/all-book-reviews/2021-first-chapters-the-tomo-75ng5”

Ko te reo te tuakiri | Language is my identity.

Ko te reo tōku ahurei | Language is my uniqueness.

Ko te reo te ora. | Language is life.