ataahua o nga kupu

You have brains in your head. You have feet in your shoes. You can steer yourself any direction you choose.

– Dr. Seuss

te ao Māori principles

There are five key principals that we as an English Department consider important as part of a holistic study at school. Please read through these and know that we will come back to them as we begin looking at texts.

- Kaitiakitanga: Guardianship of natural resources and elements of sustainability

- Rangatiratanga: Leadership, authority, Mana, empowerment, Respect

- Manaakitanga: The process of showing respect, generosity and care for others.

- Whanaungatanga: A relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides people with a sense of belonging.

- Tikanga: The customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in the social context.

Key Terms

|

is the study of words, how they are formed, and their relationship to other words in the same language. |

|

the origin of a word and the historical development of its meaning. |

|

a category to which a word is assigned in accordance with its syntactic functions. |

|

a word (other than a pronoun) used to identify any of a class of people, places, or things ( common noun ), or to name a particular one of these ( proper noun ).

|

|

a noun or noun phrase that adds information (e.g. Hermoine Granger, a student a Hogwarts, is accomplished at spells) |

|

a word used to describe an action, state, or occurrence, and forming the main part of the predicate of a sentence, such as hear, become, happen.

|

|

a word used to connect clauses or sentences or to coordinate words in the same clause (e.g. and, but, if ). |

|

word naming an attribute of a noun, such as sweet, red, or technical. |

|

a word governing, and usually preceding, a noun or pronoun and expressing a relation to another word or element in the clause, as in ‘the man on the platform’, ‘she arrived after dinner’, ‘what did you do it for ?’.

|

|

a word or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word or phrase in the same language, for example shut is a synonym of close. |

|

a word opposite in meaning to another (e.g. bad and good ).

|

|

each of two or more words having the same spelling or pronunciation but different meanings and origins. |

|

each of two or more words having the same pronunciation but different meanings, origins, or spelling, for example new and knew.

|

|

a letter representing a vowel sound, such as a, e, i, o, u.

|

|

a letter representing a consonant.

|

|

using a dictionary to give words meaning, or give the equivalent words in a different language, also obtaining information about pronunciation, origin, and usage. |

|

the letters that form (a word) in correct sequence. |

|

used to indicate either possession (e.g. Harry ‘ s book ; boys ‘ coats ) or the omission of letters or numbers (e.g. can ‘ t ; he ‘ s ; 1 Jan. ‘ 99 ). |

Learning Objectives

- Name and articulate how morphology affects words.

- Recognise that language has origins and stories (etymologies) eg Latin / Nordic etc.

- Use dictionaries to their full extent.

- Identify and discuss parts of speech.

- Incorporate accurate and effective choices of language in their writing.

- Recognise sound devices in writing.

- Explain the effect of language choices in writing.

- Identify the role of the apostrophe in writing.

- Spell words correctly using specifically taught structures and rules.

Exercises

Spelling

| tract | cease | nervous | temperature | perfectly | helicopter |

| outcome | plait | pact | barrier | gamble | curious |

| overwhelming | trace | casualty | lean | contribute | intention |

| philosophy | negative | recruit | seriously | substantial | speculate |

| gradual | tradition | illness | mayor | corruption | fundamental |

Pangram

Remember, to become faster at writing, you should practise writing out the following phrase as many times as possible for 5 minutes.

- Bored? Craving a pub quiz fix? Why, just come to the Royal Oak!

Reading Warm Up

Read the following passage. Pay special attention to the underlined words. Then, read it again, and complete the activities. Use your English book for your written answers.

I was nervous when the principal asked me to give a speech. I would have to write something to be read aloud at an assembly. The assembly was being held for Ms. Hagerty, a teacher who was leaving the school after many years. At the assembly, many people would speak about how much we would miss her.

It wasn’t hard to find speakers; everyone loved Ms. Hagerty. She was known for her kindness and would do anything to help a student learn.

She spent hours each week tutoring students after classes ended. Students and teachers had long been awed by her teaching skills. They were amazed at her ability to make almost any difficult subject easy to understand.

The assembly was being held in the auditorium, a large hall that was perfect for putting on plays and concerts. The audience was going to be huge—at least three or four hundred people.

The point of my speech was to express my appreciation for Ms. Hagerty. I wanted to show how thankful I was that she had been my teacher. To write it, I reached back into my memory, trying to recall all the great things she had done for me. It wasn’t hard. She had helped me many, many times over the years.

Even though I wasn’t used to speaking in front of people, giving the speech wasn’t hard. There was one bad moment at first when I dropped the microphone. It made a horrible screeching sound that hurt everyone’s ears. I picked it up again and calmed down. Then I talked about all the wonderful things that Ms. Hagerty had done.

“We will miss her,” I said. The audience seemed to agree. They clapped loudly when I finished speaking.

Questions

- Write the words that tell what a speech is. Then, tell what sort of person might have to give lots of speeches.

- Jot down an example of Ms. Hagerty’s kindness. Then, write what kindness means.

- Write down the nearby word that has a similar meaning to awed.

- Write down the words that tell what an auditorium is used for.

- Note the words that explain what the audience would be like. Then, tell what audience means.

- In your own words, explain what the speech writer wants to show appreciation for.

- Write a sentence telling why the speech writer reached back into memory.

- Write down the words that show what made the horrible sound.

Wondrous Words

ataahua o nga kupu

1. Free write for ten minutes. Don’t take your pen away from the page, don’t judge what you are writing, don’t edit it, don’t even read it. Keep your pen moving and writing until the full ten minutes is up. (It may help to use a timer)

2. Take a sheet of paper – preferably an old news paper or magazine with a good amount of text in it – but you can just use a blank sheet of A4

3. Cut a small square out of the sheet (about 5cm x 10cm)

4. Take this ‘window’ and put it on top of your page of free writing. The empty frame will automatically select a square of your own text and cover the rest.

5. The words that the frame selects are the beginning of a poem or story. When you read them they should either be the first few words of your new piece of writing, or they are the inspiration for a new direction.

6. If you find something that surrounds the window (as in from the news paper) then feel free to use that also.

7. Try making different text types like a poem, a story, or a song lyric.

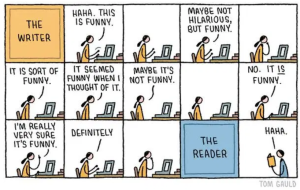

This section of the year takes practice. Practice is repetition of a skill. Have a look at this piece from TED Education on the importance of practice.

Morphemes

Morphemes are referred to as ‘units of meaning’. They can be, but are often not, whole words. They are used to help us understand words and help to improve spelling.

There are three types of morphemes in the English Language:

- Free Morphemes (Root or Base word)

- Bound Morphemes

- Derivational Morphemes

Free Morphemes

A free morpheme is a word that can stand on its own. It cannot be divided into smaller units of meaning. These are also called root or base words. Some examples are:

| girl | play | kind | help | house |

Bound Morphemes

A bound morpheme is a prefix or suffix that is added to a free morpheme to create a new meaning. A bound morpheme cannot stand on its own. Some examples are:

- ‘dis’ as in dis/appear

- dis means not (note that dis is a bound morpheme, appear is a free morpheme)

- ‘ed’ as in play/ed

- ed means past (note that ed is a bound morpheme, play is a free morpheme)

Other bound morphemes are:

- ‘s’ meaning more than one (girl/s)

- ‘er’ meaning someone who does (paint/er)

- ‘est’ meaning most (great/est)

Derivational Morphemes

A derivational morphemes provide an element of common meaning to the words in which they occur. Some examples are:

- ‘auto’ meaning self (auto/matic; auto/mobile; auto/graph)

- ‘trans’ meaning across (trans/mit; trans/port; trans/plant)

Exercises

Break these words into morphemes

- landscape

- telephone

- unhelpful

- achievements

- disinterested

Here is a list of morphemes. Combine them to make words.

- ed

- er

- un

- ment

- ly

- sing

- work

- sleep

- ship

- develop

The Parts of Speech

Every word in the English language can be categorised into the Parts of Speech. Knowing these Parts of Speech allows us to use language more effectively. The main pats of speech are listed here.

Nouns

If we think of words as the body then nouns must be the bones. Sentences that contain strong bones explore meaning and emotion through things that we can connect and relate to.

In your own writing, try to use nouns that are tangible (things you can touch, or see, or smell) rather than abstract. Look at this extract from a poem by Emily Dickinson and pay close attention to how she uses nouns.

That perches in the soul,

And sings the tune without the words

And never stops at all.

Great authors and poets (like Emily Dickinson) show us that concrete language is the ally of abstract thought, not its enemy.

The term noun comes from the Latin word nomen, which means name. Nouns are used to name a person, place or thig. Nouns can be proper, common, collective, and abstract.

Proper Nouns: always begin with a capital letter and are the names of people, places, organisations and specific things.

- While working at Countdown last Wednesday, Kelly saw an old friend from Christchurch.

Common Nouns: the names gives to classes of persons, places or things. They are non-specific.

- I bought a book from the shop next to the river.

Collective Nouns: The nouns used to name a group or collection of things.

- A swarm of bees landed on a bunch of bananas that were near the family.

Abstract Nouns: The names of things than cannot be seen or touched.

- James was in a state of jealousy at the new found freedom after the virus.

Exercises

In the following paragraphs, highlight all nouns, then categorise them using the following 4 areas. Note: not all types of nouns will be in every example eg. some paragraphs may have 3-4 proper nouns, and some may have 0.

Make a chart like the example below for all the exercises.

Example: “They thought that was pretty funny, but I meant it. I felt lousy. The hospital got real quiet after they left. The only noise was the nurse’s soft footsteps and Soda’s light breathing. Darry looked down at him and grinned half-heartedly. “He didn’t get much sleep this week,” he said softly. “He hardly slept at all.”

- (‘The Outsiders’ by S.E. Hinton)

- She drives me crazy. Sometimes I have to grit my teeth to control myself. She wants to know why other Italian girls have Italian boyfriends and I don’t. If I want to go out with Australians, she objects. “What do they know about culture?” she asks. “Do they understand the way we live?” (‘Looking for Alibrandi’ by Melina Marchetta)

- Even before he signs his name, he feels the tears welling up inside. They don’t seem to come from his eyes but from deep in his gut. It’s a heaving so powerful it hurts his stomach and his lungs. His eyes flood, and the pain inside is so great, he’s certain it will kill him right here, right now. But he doesn’t die, and in time the storm inside him passes, leaving him weak in every joint and muscle of his body. He feels like he needs Sonia’s cane just to walk again. (‘Unwind’ by Neal Shusterman)

- Suddenly Kahu made a quick, darting gesture. She picked something up, inspected it, appeared satisfied with it, and went back to the dolphins. Slowly the girl and the dolphins rose towards us. But just as they were midway, Kahu stopped again. She kissed the dolphins goodbye and gave Nanny Flowers a heart attack by returning to the reef. She picked up a crayfish and resumed her upward journey. The dolphins were like silver dreams as they disappeared. (‘The Whale Rider‘ by Witi Ihimaera)

- Ender knew what was happening from the moment they brought him in. Everyone expected him to go commander early. Perhaps not this early, but he had topped the standings almost continuously for three years, no one else was remotely close to him, and his evening practices had become the most prestigious group in the school. There were some who wondered why the teachers had waited this long. He wondered which army they’d give him. Three commanders were graduating soon, including Petra, but it was beyond hope for them to give him Phoenix Army—no one ever succeeded to command of the same army he was in when he was promoted. (‘Ender’s Game’ by Orson Scott Card)

- Bruno considered the dilemma he was in. On the one hand his sister and he had one crucial thing in common: they weren’t grown ups. And although he had never bothered to ask her, there was every chance that she was just as lonely as he was at Out-With. After all, back in Berlin she had had Hilda and Isobel and Louise to play with; they may have been annoying girls but at least they were her friends. Here she had no one at all except her collection of lifeless dolls. Who knew how mad Gretel was after all? Perhaps she thought the dolls were talking to her. (‘The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas’ by John Boyne)

Pronouns

The term pronoun is to use a word in place of the noun. There must be a reference link to a noun so that the audience know who or what is being replaced. Read the following example

- I saw Philippa: Philippa was at the beach.

- I saw Philippa: she was at the beach.

The pronoun she is used so that the name Philippa doesn’t need to be repeated. As the audience, we know that she refers to Philippa.

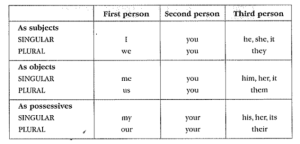

Personal Pronouns: Used to replace names of persons and things and can be singular or plural. Look at the following table.

Relative Pronouns: include who, whom, whose, which and that. These can replace nouns especially when used to combine sentences. Look at the following example.

- I saw the boy. The boy was crying.

- I saw the boy who was crying.

Interrogative Pronouns: these are used in questions. They are who, what which, whom and whose. Here are some examples of their use.

- Who is going to help me?

- What are you doing?

- To whom are you referring?

Indefinite Pronouns: Words like everybody, someone, no-one, anybody, nobody, something, and anything that do not stand for any specific person, place or thing.

- Nobody can help if something goes wrong.

Exercises

Read the following extract, and then answer the questions that follow

Alice’s Time Up North

When Alice came to live in the tiny town of Kaitaia it went almost completely under water.

It was the year of the big floods up north and Alice found herself right in the middle of them.

Alice was staying with her aunt and uncle and her cousins Linda and Thomas because her mother was so sick in hospital in Auckland. Their house was not far from the deep creek where Thomas took her fishing, and it looked out onto the most perfectly beautiful lake. It was called Fairy Lake by the locals but Alice thought it should be called Birdsong lake because you could hear the birds so clearly. So many beautiful birds. It wasn’t like this at home where she lived in a tiny flat in Eden Terrace, right in the heard of the city of Auckland. Mum was always saying there must have been a garden like Eden there once. Well, there certainly weren’t birds like this in Auckland – so noisy and festive when she woke every morning. It helped, in a way, to ease the ache of facing yet another day without her mum

.

- What sort of nouns are Alice, Kaitaia, Linda, Thomas?

- List three common nouns from the extract.

- What part of speech is her in ‘her mother’?

- What part of speech is their in ‘their house’?

- What noun does it refer to in ‘Their house was not far from a deep creek, and it looked out onto …’

- What type of noun is ache?

- What proper noun does she refer to in ‘It wasn’t like this at home where she lived…’?

- Who does her in ‘without her mum’ refer to? Alice or Linda?

Articles

There are only three articles in the English language: a, an and the. Articles can be difficult for English learners to use correctly because many languages don’t have them (or don’t use them in the same way).

Although articles are their own part of speech, they’re technically also adjectives! Articles are used to describe which noun you’re referring to. Maybe thinking of them as adjectives will help you learn which one to use:

- A — A singular, general item.

- An — A singular, general item. Use this before words that start with a vowel.

- The — A singular or plural, specific item.

Simply put, when you’re talking about something general, use a and an. When you’re speaking about something specific, use the. “A cat” can be used to refer to any cat in the world. “The cat” is used to refer to the cat that just walked by.

Exercises

Identify the articles in the following extracts. The first one has been done for you.

- Worse, the suits were confining. It was harder to make precise movements, since the suits bent just a bit slower, resisted a bit more than any clothing they had ever worn before. (‘Ender’s Game’ by Orson Scott Card)

- This time when he went out to the sea to sulk he took my dinghy, the one with the motor in it. (‘The Whale Rider’ by Witi Ihimaera)

- Becky and Todd and some others reckoned there must be some way we could fit Simon in, even if we just showed him in a head a shoulders shot, or maybe sitting behind a table. (‘See ya, Simon’ by David Hill)

- Mr. Jones, of the Manor Farm, had locked the hen-houses for the night, but was too drunk to remember to shut the pop-holes. (‘Animal Farm’ by George Orwell)

- We didn’t sleep for twenty hours, but we gave it our best shot. I stirred a couple of times during the morning, turned over, had a look at Lee, who seemed restless, glanced at Robyn beside me, who was sleeping like an angel, and dropped back into my heavy sleep. (‘Tomorrow, When the War Began’ by John Marsden)

- Lennie lost his smile. He advanced a step into the room, then remembered and backed to the door again. “I looked at ‘em a little. Slim says I ain’t to pet ‘em very much.” (‘Of Mice and Men’ by John Steinbeck)

- And this was my timetable when I lived at home with Father and I thought that Mother was dead from a heart attack (this was the timetable for a Monday and also it is an approximation). (‘The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime” by Mark Haddon)

- We browsed around for a while looking at all the stalls with their trinkets and T-shirts and spent half an hour in Gap and Abercrombie trying on clothes we knew we couldn’t afford to buy. The crowds got to us after a while. (‘Looking for Alibrandi’ by Melina Marchetta)

- Connor’s relief is so great, it takes the wind right out of him. He can’t even offer a thank-you. (‘Unwind’ by Neal Shusterman)

- Still, he had heard enough to know that there was a chance they might be returning to Berlin, and to his surprise he didn’t know how to feel about that. (‘The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas’ by John Boyne)

Adjectives

Primary school teachers often encourage their pupils to jazz up their writing with ‘sizzle words’: that is, with lots of adjectives and adverbs. So, a cat inevitably becomes ‘a creeping cat’ or ‘a mysterious cat’ or ‘a fluffy cat’. No one would deny the impact of a well-placed adjective. However, a sentence crammed with too many artificial additives can ruin the effectiveness of that piece of writing. Only use adjectives when they contribute new information to the sentence.

Adjectives are words that add meaning to a noun or a pronoun. They are describing words that modify nouns.

Descriptive Adjectives: are words like thin, black, hot, old. For example:

- thin pastry

- black shoes

- hot day

- old house

Numeral Adjectives: add meaning related to numbers. They tell us how many there are, or how an item is ranked in comparison with others, for example:

- There were eight cars in the garage.

- He was the fourth person to become sick.

Degrees of comparison: are indicated by the morphemes -er and -est, for example.

- Rick and Morty is a funny show

- Family Guy is a funnier show

- The Simpsons is still the funniest show.

Degrees of Comparison can also be shown through the words more and most, for example:

- Mathematics is a challenging subject

- Chemistry is a more challenging subject

- Nuclear Physics is the most challenging subject that there is

The three degrees of comparison are called positive, comparative, and superlative.

NB: Although adjectives often occur next to the noun they describe, this is not always the case. See these examples:

- His car was blue.

- A dog, fierce and growling, ran towards me.

Exercises

Here are three stanzas from a poem by Henry Lawson. Copy it into your workbook and underline the adjectives.

A cloud of dust on the long, white road,

And the teams go creeping on

Inch by inch the weary load;

And by the power of the green-hide goad

The distant goal is won.

With eyes half-shut to the blinding dust,

And necks to the yokes bent low,

The beasts are pulling as bullocks must;

And the shining tires might almost rust

While the spokes are turning slow.

With face half-hid by a broad-brimmed hat,

That shades from the heat’s white waves,

And shouldered whip, with its green-hide plait,

The drive plods with a gait like that,

Of his weary, patient slaves.

The Dictionary

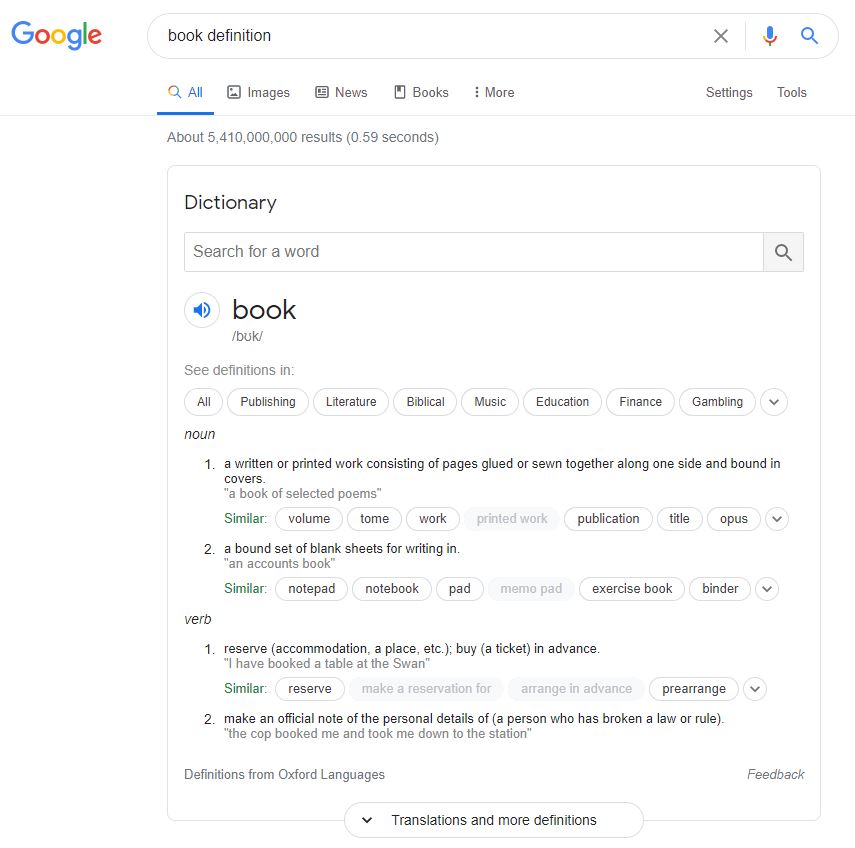

The dictionary acts as a way of finding out more about words. While we don’t use dictionaries like we used to (every class used to have to have a complete set of dictionaries for all students to assist with their writing) the emphasis on them is still the same. Now, we are more likely to check Google for the definition of a word.

Here is how to search for a definition:

- In the search bar, enter the word you are seeking the definition for, and add ‘definition’ at the end. For example

- The next screen should provide you with the information that you need, as below.

There are a few things of importance here.

- The Sound Icon: This allows you to hear the word pronounced correctly. It is great for when you aren’t sure how to say something tricky – like “manoeuvre”.

- The phonetic alphabet: (You should use the sound icon for phonetic) This allows you to work out how to say the word based upon the sounds in the English language. You do not need to know these in Year 9. This is just for your interest (if you are interested you can look at them here). Did you know there are 44 phonemes in the English language? If you went to school in New Zealand from Year 1 or Year 2, you actually already know these. Every English word is made from a selection of these 44 phoneme sounds.

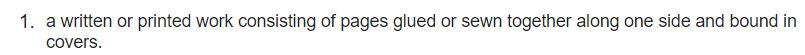

- Part of Speech: The Google dictionary also tells you the type of word that it is. It provides you with the type of speech, and allows you to note the various versions of the word that you can use.

- Definition: The main reason for using the dictionary is to provide you with the information that you need about the word. Be careful that you are looking at the right type of word. For example, ‘book’ can be a noun or a verb, so just make sure you are looking at the right version of the word.

- Example: Each definition will always provide an example of how that word can be used (in that version).

NB: If you expand the window at the bottom of the definition you will get more options for definitions and examples. - Synonyms: Another popular book at school is the thesaurus. The thesaurus provides alternative words (synonyms) that can be used. There are a few options available on Google for this purpose. It is not extensive (but you can also use the same technique of searching for a word and ‘synonym’ for a similar function to a thesaurus – eg ‘book synonym’)

- Phrases: Often the word will be associated with idioms or phrases. Here you have the opportunity to search through some common phrases that include the word.

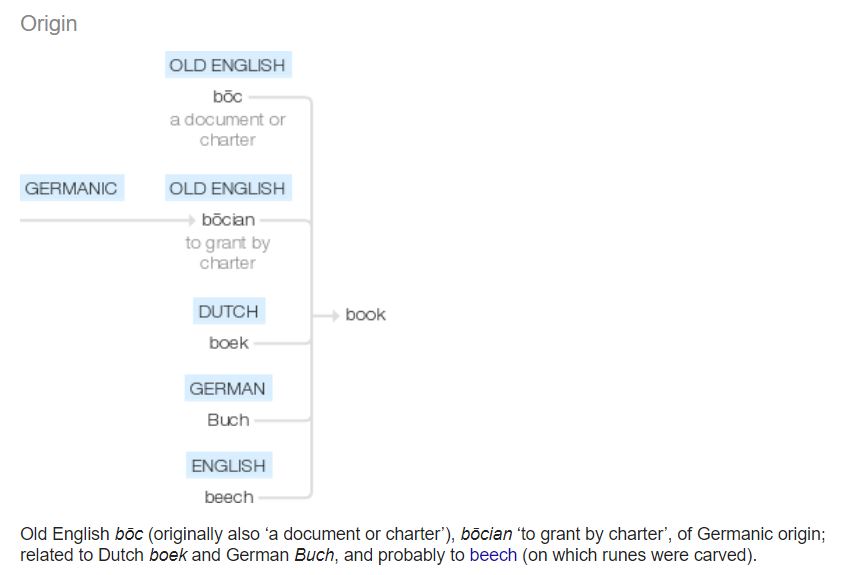

- Etymology: The etymology of a word is where it came from. All English words started off as other languages (German / French / Spanish / Indian etc). You don’t need to know where all the words you use come from, but you should realise that English came from other languages and was (and is) adaptable. In the example below you will see that ‘book’ came from the Germanic word ‘bōc’. The key learning here is that words come from somewhere, and the story of the words is called the etymology.

In some classes this term (and each term following) you will be reading through some texts together. This is part of a wider reading programme that you will be required to follow throughout the term.

Each chapter will have some questions on books that you may like to think about. If your class is not studying a text, you may like to look at these questions yourself.

- What type of text is it? (ie novel, short stories, poems etc)

- What is the name of the book?

- What image is on the cover?

- Based on the name and the image on the cover, what do you think the book is about?

- How does the blurb add to your knowledge?

- What is the genre of the story? (ie action, romance, adventure)

After reading the first chapter

- From whose perspective is the story told?

- Who do you think is the main character?

- What do you learn in the first chapter?

You may also like to try using Reading Circles of five people. Each person is given one of the following roles and you can work through the story together.

- “The Leader” – facilitates the discussion, preparing some general questions and ensuring that everyone is involved and engaged.

- “The Summariser” – gives an outline of the plot, highlighting the key moments in the book. More confident readers can touch upon its strengths and weaknesses.

- “The Word Master” – selects vocabulary that may be new, unusual, or used in an interesting way.

- “The Passage Person” – selects and presents a passage from that they feel is well written, challenging, or of particular interest to the development of the plot, character, or theme.

- “The Connector” – draws upon all of the above and makes links between the story and wider world. This can be absolutely anything; books, films, newspaper articles, a photograph, a memory, or even a personal experience, it’s up to you. All it should do is highlight any similarities or differences and explain how it has brought about any changes in your understanding and perception of the book.

An extract from Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbit

The road that led to Treegap had been trod out long before by a herd of cows who were, to say the least, relaxed. It wandered along in curves and easy angles, swayed off and up in a pleasant tangent to the top of a small hill, ambled down again between fringes of bee-hung clover, and then cut sidewise across a meadow. Here its edges blurred. It widened and seemed to pause, suggesting tranquil bovine picnics: slow chewing and thoughtful contemplation of the infinite. And then it went on again and came at last to the wood. But on reaching the shadows of the first trees, it veered sharply, swung out in a wide arc as if, for the first time, it had reason to think where it was going, and passed around.

On the other side of the wood, the sense of easiness dissolved. The road no longer belonged to the cows. It became, instead, and rather abruptly, the property of people. And all at once the sun was uncomfortably hot, the dust oppressive, and the meager grass along its edges somewhat ragged and forlorn. On the left stood the first house, a square and solid cottage with a touch-me-not appearance, surrounded by grass cut painfully to the quick and enclosed by a capable iron fence some four feet high which clearly said, “Move on—we don’t want you here.” So the road went humbly by and made its way, past cottages more and more frequent but less and less forbidding, into the village. But the village doesn’t matter, except for the jailhouse and the gallows. The first house only is important; the first house, the road, and the wood.

There was something strange about the wood. If the look of the first house suggested that you’d better pass it by, so did the look of the wood, but for quite a different reason. The house was so proud of itself that you wanted to make a lot of noise as you passed, and maybe even throw a rock or two. But the wood had a sleeping, otherworld appearance that made you want to speak in whispers. This, at least, is what the cows must have thought: “Let it keep its peace; we won’t disturb it.”

Whether the people felt that way about the wood or not is difficult to say. There were some, perhaps, who did. But for the most part the people followed the road around the wood because that was the way it led. There was no road through the wood. And anyway, for the people, there was another reason to leave the wood to itself: it belonged to the Fosters, the owners of the touch-me-not cottage, and was therefore private property in spite of the fact that it lay outside the fence and was perfectly accessible.

The ownership of land is an odd thing when you come to think of it. How deep, after all, can it go? If a person owns a piece of land, does he own it all the way down, in ever narrowing dimensions, till it meets all other pieces at the center of the earth? Or does ownership consist only of a thin crust under which the friendly worms have never heard of trespassing?

In any case, the wood, being on top—except, of course, for its roots—was owned bud and bough by the Fosters in the touch-me-not cottage, and if they never went there, if they never wandered in among the trees, well, that was their affair. Winnie, the only child of the house, never went there, though she sometimes stood inside the fence, carelessly banging a stick against the iron bars, and looked at it. But she had never been curious about it. Nothing ever seems interesting when it belongs to you—only when it doesn’t.

And what is interesting, anyway, about a slim few acres of trees? There will be a dimness shot through with bars of sunlight, a great many squirrels and birds, a deep, damp mattress of leaves on the ground, and all the other things just as familiar if not so pleasant—things like spiders, thorns, and grubs.

In the end, however, it was the cows who were responsible for the wood’s isolation, and the cows, through some wisdom they were not wise enough to know that they possessed, were very wise indeed. If they had made their road through the wood instead of around it, then the people would have followed the road. The people would have noticed the giant ash tree at the center of the wood, and then, in time, they’d have noticed the little spring bubbling up among its roots in spite of the pebbles piled there to conceal it. And that would have been a disaster so immense that this weary old earth, owned or not to its fiery core, would have trembled on its axis like a beetle on a pin.

Taken from “https://us.macmillan.com/excerpt?isbn=9781250059291”

Ko te reo te tuakiri | Language is my identity.

Ko te reo tōku ahurei | Language is my uniqueness.

Ko te reo te ora. | Language is life.