kōrero

Learn continually. There is always one more thing to learn.

– Steve Jobs

te ao Māori principles

There are five key principals that we as an English Department consider important as part of a holistic study at school. Please read through these and know that we will come back to them as we begin looking at texts.

- Kaitiakitanga: Guardianship of natural resources and elements of sustainability

- Rangatiratanga: Leadership, authority, Mana, empowerment, Respect

- Manaakitanga: The process of showing respect, generosity and care for others.

- Whanaungatanga: A relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides people with a sense of belonging.

- Tikanga: The customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in the social context.

Key Terms

|

the interactive art of using words and actions to reveal the elements and images of a story while encouraging the listener’s imagination. |

|

the formation of clear and distinct sounds in speech. |

|

a specified state of growth or advancement. |

|

providing clarity of a point or overall premise of a communication. |

|

the structure and shape of a story. |

|

relating to bodily structure. |

|

a region of the brain concerned with the production of speech, located in the cortex of the dominant frontal lobe. |

|

a flap of cartilage behind the root of the tongue, which is depressed during swallowing to cover the opening of the windpipe. |

|

the hollow muscular organ forming an air passage to the lungs and holding the vocal cords in humans and other mammals; the voice box. |

|

the roof of the mouth, separating the cavities of the mouth and nose in vertebrates. |

|

a large membranous tube reinforced by rings of cartilage, extending from the larynx to the bronchial tubes and conveying air to and from the lungs; the windpipe. |

|

folds of membranous tissue which project inwards from the sides of the larynx to form a slit across the glottis in the throat, and whose edges vibrate in the airstream to produce the voice. |

|

the circumstances that form the setting for an event, statement, or idea, and in terms of which it can be fully understood. |

|

occurring or done immediately. |

|

the assembled spectators or listeners at a public event such as a play, film, concert, or meeting. |

|

a talk, especially an informal one, between two or more people, in which news and ideas are exchanged. |

|

a long speech by one actor in a play or film, or as part of a theatrical or broadcast programme. |

|

a speech that has been prepared using a drafting and redrafting process. |

|

the ability for two speakers to have equal contributions within the context of a conversation. |

Learning Objectives

- Appreciate the role of spoken language in a range of contexts.

- To recognise the parts of the body that affect speaking.

- To identify that own speaking style is dependent on context.

- To listen for verbal cues in others and recognise the skill others have in communicating.

- Recognise and use the features of spoken language including formal and informal spoken texts.

- Recognise differences between spoken and written texts.

- Use appropriate vocabulary to identify aspects of spoken language.

- Appreciate the different and appropriate uses of spoken language.

- Become a more effective speaker.

Exercises

Spelling

| shame | suspicion | explode | accompany | publication | superb |

| fiscal | license | sauce | definition | minor | install |

| sensible | peak | gallery | trend | pace | integrate |

| dare | anxious | assistance | preserve | prosecute | triumph |

| participate | broker | column | rescue | overnight | specialise |

Pangram

Remember, to become faster at writing, you should practise writing out the following phrase as many times as possible for 5 minutes.

- Sphinx of black quartz, judge my vow!

Reading Warm Up

Read the following passage. Pay special attention to the underlined words. Then, read it again, and complete the activities. Use your English book for your written answers.

| Jonathan Harker’s Journal

3 May. Bistritz.–Left Munich at 8:35 P.M., on 1st May, arriving at Vienna early next morning; should have arrived at 6:46, but train was an hour late. Buda-Pesth seems a wonderful place, from the glimpse which I got of it from the train and the little I could walk through the streets. I feared to go very far from the station, as we had arrived late and would start as near the correct time as possible. The impression I had was that we were leaving the West and entering the East; the most western of splendid bridges over the Danube, which is here of noble width and depth, took us among the traditions of Turkish rule. We left in pretty good time, and came after nightfall to Klausenburgh. Here I stopped for the night at the Hotel Royale. I had for dinner, or rather supper, a chicken done up some way with red pepper, which was very good but thirsty. (Mem. get recipe for Mina.) I asked the waiter, and he said it was called “paprika hendl,” and that, as it was a national dish, I should be able to get it anywhere along the Carpathians. I found my smattering of German very useful here, indeed, I don’t know how I should be able to get on without it. Having had some time at my disposal when in London, I had visited the British Museum, and made search among the books and maps in the library regarding Transylvania; it had struck me that some foreknowledge of the country could hardly fail to have some importance in dealing with a nobleman of that country. I find that the district he named is in the extreme east of the country, just on the borders of three states, Transylvania, Moldavia, and Bukovina, in the midst of the Carpathian mountains; one of the wildest and least known portions of Europe. I was not able to light on any map or work giving the exact locality of the Castle Dracula, as there are no maps of this country as yet to compare with our own Ordance Survey Maps; but I found that Bistritz, the post town named by Count Dracula, is a fairly well-known place |

Questions:

- Surface Level

- Between which cities did Johnathan Harker travel?

- At what time and on what date did Johnathan leave Munich?

- What form or mode of transport was Johnathan using?

- What are the main ingredients of ‘paprika hendl’?

- What does Johnathan note to himself as a reminder?

- To get ‘paprika henl’ in Carpathians

- To get a recipe for Mina

- To get a map showing Castle Dracula

- Discovering Techniques

- Look up the following words in the thesaurus and write out the synonyms. They need to have the same meaning as in the passage.

- glimpse

- impression

- splendid

- nightfall

- thirsty

- time at my disposal

- smattering

- extreme

- Look up the following words in the thesaurus and write out the synonyms. They need to have the same meaning as in the passage.

Listening Warm Up

In groups of 5 have a go at telling each other one thing from the following selection. You cannot repeat a starter phrase once it has been used. At the end your teacher will ask for a summary from the group.

- something funny that happened to me this week was…

- a place outside of Auckland that I have travelled to recently was…

- my favourite meal would have to be…

- if I was principal the first thing I would change about this school is…

- the last movie I went to see was…

Speaking

kōrero

Speaking is something that we do every single day. It is something we do almost without knowing it. It is different to the written word. I have thought about these words, changed them, edited them. Speaking is different.

Here are some features you might have noted as occurring in spoken text. This list also includes features you would find in both informal and formal spoken texts.

- it is instant – you can say things quickly (but we all have things that we wish we hadn’t said)

- you an explain things more, should the listener not understand (unlike writing)

- almost everyone can talk

- there is usually someone else involved (an audience of some description)

- the situation or context that binds the communication together will determine the subject (e.g. you wouldn’t discuss elements of algebra in the middle of a rugby scrum.)

- conversation is part of speaking. It is controlled by one speaker and then another. This is called turn-taking.

- spoken language is often interrupted by a listener and this is often seen as acceptable. A speech is different, it is not often interrupted.

- a speaker will interrupt their own speaking with words like ‘um’, ‘er’ or ‘like’. This can be used to create some time to think, or to create an effect.

- the listener will often respond with positive words like ‘yes’ or ‘that’s right’ at pauses. If they do not do this you can think that they are not concentrating.

- sentences are often short phrases or fragments of sentences.

- sentences are not always begun or finished the way a written sentence is.

- sentences in spoken words often include repetition.

- tone and body language have a major impact on how a message is received by an audience.

Let’s look at some of the specifics of how we speak. This is called The Mechanics. In fact, the word Mechanics is used a lot in English, it means the machinery or working parts of something. You will hear that word a lot.

This lady is a speech therapist so her job is to help those who struggle with speaking. While the vast majority of you won’t have these issues, the science behind it is interesting and worth knowing to help you on your own speaking journey.

For the second time here is Julian Treasure. In the previous section (Listening) we listened to him speak on the importance of hearing properly.

Here he is speaking about talking. It’s worth considering your own position as you listen to this talk.

Speech

Speech is defined as the ability to communicate thoughts, ideas, or other information by means of sounds that have clear meaning to others.

Many animals make sounds that might seem to be a form of speech. For example, one may sound an alarm that a predator is in the area. The sound warns others of the same species that an enemy is in their territory. Or an animal may make soothing sounds to let offspring know that a parent is present. Most scientists regard these sounds as something other than true speech.

True speech consists of two essential elements. First, an organism has to be able to develop and phrase thoughts to be expressed. Second, the organism has to have the anatomical equipment with which to utter clear words that convey those thoughts. Most scientists believe that humans are the only species capable of speech.

Speech has been a critical element in the evolution of the human species. It is a means by which a people’s history can be handed down from one generation to the next. It enables one person to convey knowledge to a roomful of other people. It can be used to amuse, to rouse, to anger, to express sadness, to communicate needs that arise between two or more humans.

The anatomy of speech

Spoken words are produced when air expelled from the lungs passes through a series of structures within the chest and throat and passes out through the mouth. The structures involved in that process are as follows: air that leaves the lungs travels up the trachea (windpipe) into the larynx. (The larynx is a longish tube that joins the trachea to the lower part of the mouth.) Two sections of the larynx consist of two thick, muscular folds of tissue known as the vocal cords. When a person is simply breathing, the vocal cords are relaxed. Air passes through them easily without producing a sound.

When a person wishes to say a word, muscles in the vocal cords tighten up. Air that passes through the tightened vocal cords begins to vibrate, producing a sound. The nature of that sound depends on factors such as how much air is pushed through the vocal cords and how tightly the vocal cords are stretched.

The moving air—now a form of sound—passes upward and out of the larynx. A flap at the top of the larynx, the epiglottis, opens and closes to allow air to enter and leave the larynx. The epiglottis is closed when a person is eating—preventing food from passing into the larynx and trachea—but is open when a person breathes or speaks.

Once a sound leaves the vocal cords, it is altered by other structures in the mouth, such as the tongue and lips. A person can form these structures into various shapes to make different sounds. Saying the letters “d,” “m,” and “p” shows how your lips and tongues are involved in this process.

Other parts of the mouth also contribute to the sound that is finally produced. These parts include the soft palate (roof) at the back of the mouth, the hard or bony palate in the front, and the teeth. The nose also provides an alternate means of issuing sound and is part of the production of speech. Movement of the entire lower jaw can alter the size of the mouth cavern and influence the tone and volume of the speech.

The tongue is the most agile body part in forming sounds. It is a powerful muscle that can take many shapes—flat, convex, curled—and can move front and back to contact the palate, teeth, or gums. The front of the tongue may move upward to contact the hard palate while the back of the tongue is depressed. Essentially these movements open or obstruct the passage of air through the mouth. During speech, the tongue moves rapidly and changes shapes constantly to form partial or complete closure of the vocal tract necessary to manufacture words.

The brain

Other animals have anatomical structures similar to those described above. Yet, they do not speak. The reason that they lack speech is that they lack the brain development needed to form ideas that can be expressed in words.

In humans, the part of the brain that controls the anatomical structures that make speech possible is known as Broca’s area. It is located in the left hemisphere (half) of the brain for right-handed and most left-handed people. Nerves from Broca’s area lead to the neck and face and control movements of the tongue, lips, and jaws.

The portion of the brain in which language is recognized is situated in the right hemisphere. This separation leads to an interesting phenomenon: a person who loses the capacity for speech still may be able to understand what is spoken to him or her and vice versa.

The Audience

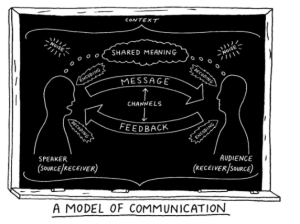

At its simplest, communication consists of a speaker, a message, and a receiver. Following this model, your speech represents the message. Naturally, this makes you the speaker. To whom you speak then, represents the receiver: in this case, your audience. When looking at this most basic model of communication, your audience represents one-third of the communication equation, proving it is one of the three most important elements to consider as you craft your speech.

Elements to Consider About Your Audience

Your audience may be represented by a variety of distinguishing characteristics and commonalities, often referred to as demographics. It is important to remember that you should not stereotype or make assumptions about your audience based on their demographics; however, you can use these elements to inform the language, context, and delivery of your speech. The first question you should ask yourself, before you begin crafting your speech, is this: “Who is my audience?”

As you begin to answer this question for yourself, here are some key elements to consider as you begin to outline and define your audience:

- Age: What age ranges will be in your audience? What is the age gap between you and your audience members? Age can inform what degree of historical and social context they bring to your speech as well as what knowledge base they have as a foundation for understanding information.

- Culture/Race: While these are two separate demographics, one informs the other and vice versa. Race and culture can influence everything from colloquialisms to which hand gestures may or may not be appropriate as you deliver your speech.

- Gender: Is your audience mostly women? Men? A mix of the two? It is important to consider your gender and your audience, as the gender dynamic between you and your audience can impact the ways in which your speech may be received.

- Occupation/Education: Just as age, culture, race, and gender factor into your audience’s ability to relate to you as speaker, so may occupation and education. These elements also help to give you an understanding of just how much your audience already may or may not know about your given subject.

- Values and Morals: While these may not be readily apparent, they can factor prominently into your ability to be likable to your audience. Particularly if you are dealing with controversial material, your audience may already be making judgments about you based on your values and morals as revealed in your speech and thus impacting the ways in which they receive your message.

Key Takeaways

When we speak we change what we say and how we say it, depending on who we are speaking to. Think about your daily conversations: when you speak to your parents in the morning you speak differently to the way you speak to your friends at lunch time, and that’s different again to the way you speak to your teacher during class time.

What you are doing is called code-switching. That means that you are consciously adapting to the needs of your audience. Sometimes that can mean you speak a different language to your parents or members of your family or you use more formal language depending on who you are speaking to.

Think about your own conversations in a day:

- How do you speak to your parents? What language do you use?

- How formal are your conversations with your friends? What language do you use? Is there a variety of languages in your friend group?

- What would be the best language choice for an email to your teacher?

- formal

- informal

- conversational

- Of the list of audience features above, what do you need to consider when speaking in front of your class?

In some classes this term (and each term following) you will be reading through some texts together. This is part of a wider reading programme that you will be required to follow throughout the term.

Each chapter will have some questions on books that you may like to think about. If your class is not studying a text, you may like to look at these questions yourself.

- What type of text is it? (ie novel, short stories, poems etc)

- What is the name of the book?

- What image is on the cover?

- Based on the name and the image on the cover, what do you think the book is about?

- How does the blurb add to your knowledge?

- What is the genre of the story? (ie action, romance, adventure)

After reading the last chapter you are up to….

- From whose perspective is the story told?

- Who do you think is the main character?

- What do you learn in this chapter?

An excellent speech to watch

In this TED talk from Trent Hohaia is a great example of listening to Māori storytelling. No need to make notes on this, just enjoy thinking and learning about the Māori storytelling culture.

Ko te reo te tuakiri | Language is my identity.

Ko te reo tōku ahurei | Language is my uniqueness.

Ko te reo te ora. | Language is life.