whakakīkī

There are only two types of speakers in the world. 1. The nervous and 2. Liars.

– Mark Twain

te ao Māori principles

There are five key principals that we as an English Department consider important as part of a holistic study at school. Please read through these and know that we will come back to them as we begin looking at texts.

- Kaitiakitanga: Guardianship of natural resources and elements of sustainability

- Rangatiratanga: Leadership, authority, Mana, empowerment, Respect

- Manaakitanga: The process of showing respect, generosity and care for others.

- Whanaungatanga: A relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides people with a sense of belonging.

- Tikanga: The customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in the social context.

Key Terms

|

the activity of telling or writing stories. |

|

the art of effective or persuasive speaking or writing, especially the exploitation of figures of speech and other compositional techniques. |

|

the principles relating to or inherent in a sphere or activity, especially when concerned with power and status. |

|

a set of criteria or stated values in relation to which measurements or judgements can be made. |

|

a reason or set of reasons given in support of an idea, action or theory. |

|

the action or process of persuading someone or of being persuaded to do or believe something. |

|

a thing made or adapted for a particular purpose. |

|

relating to the philosopher, Aristotle or his philosophy. |

|

a speaker or writer’s credibility. |

|

a speaker or writer’s appeal to emotional content. |

|

a speaker or writer’s appeal to logical or fact-based content. |

|

the reason for which something is done or created or for which something exists. |

|

a person or thing that is being discussed, described, or dealt with. |

|

the assembled spectators or listeners at a public event such as a play, film, concert, or meeting. |

|

the aspect of someone’s character that is presented to or perceived by others. |

|

evidence or argument establishing a fact or the truth of a statement. |

|

showing sound reasoning, and relevant experience or expertise. |

|

a high level of moral character |

|

demonstrating good intentions towards the audience. |

Learning Objectives

- Appreciate the importance of the audience when speaking.

- Define rhetoric as part of the persuasion process.

- Identify the use of Aristotelian aspects of ethos, pathos and logos in a speech or piece of writing.

- Listen closely to language used by speakers to determine the rationale and purpose of the speaker.

- Incorporate elements of persuasion in own writing.

- Appreciate the use of rhetoric for persuasive purposes.

- Define framing as part of the rhetoric process.

- Become a more effective speaker.

Exercises

Spelling

| operator | nurse | impression | ultimate | homeless | reverse |

| combat | intense | incredible | stomach | counterpart | consequence |

| percentage | excerpt | category | miner | proceed | species |

| judgement | objective | resistance | silence | remarkable | transform |

| opera | slice | surgery | cancel | passion | takeover |

Pangram

Remember, to become faster at writing, you should practise writing out the following phrase as many times as possible for 5 minutes.

- Both fickle dwarves jinx my pig quiz.

Reading Warm Up

Read the following passage from Helen Keller.

| Try to imagine what it would be like to be both blind and deaf at the same time. The world around you would be completely dark and silent. It would be very hard to understand anything or to communicate with another person. This is the kind of world that young Helen Keller lives in, and there doesn’t seem to be much hope for her. But her teacher Miss Sullivan is determined to help her. And one day she finds a new way for Helen to connect to the world around her. As the story opens, Helen describes her first experiences with Miss Sullivan, her new teacher: The morning after my teacher came she led me into her room and gave me a doll. . . . When I had played with it a little while, Miss Sullivan slowly spelled into my hand the word “d-o-l-l.” I was at once interested in this finger play and tried to imitate it. I did not know that I was spelling a word or even that words existed; I was simply making my fingers go in monkey-like imitation. We walked down the path to the well-house, attracted by the fragrance of the honeysuckle with which it was covered. Some one was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout. As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten—a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that “w-a-t-e-r” meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. I left the well-house eager to learn. Everything had a name, and each name gave birth to a new thought. It would have been difficult to find a happier child than I was as I lay in my crib at the close of that eventful day and lived over the joys it had brought me, and for the first time longed for a new day to come. |

Questions:

-

-

- A narrative essay is a true story about real events. Is this a narrative essay? How do you know?

- An author’s purpose may be to instruct, to entertain, to persuade, or to express ideas. What do you think the purpose of this writing is? And what evidence do you have for this?

- Why does Helen’s discovery of words make her so happy?

- What smell attracted Helen and Anne Sullivan to the well-house?

- How did Sullivan teach Keller what w-a-t-e-r means?

- How do you think Sullivan feels about what happened?

- Complete the chart to figure out why Keller talk about a certain event in her autobiographical narrative

-

| Event From Narrative | Author’s Feelings and Thoughts | Why Is It Included? |

| Helen connects the word w-a-t-e-r with water from the pump

|

Listening Warm Up

In groups of 5 have a go at telling each other one thing from the following selection. You cannot repeat a starter phrase once it has been used. At the end your teacher will ask for a summary from the group.

- something funny that happened to me this week was…

- a place outside of Auckland that I have travelled to recently was…

- my favourite meal would have to be…

- if I was principal the first thing I would change about this school is…

- the last movie I went to see was…

Speaking

The DNA of Story

Ever since the first grunts were made by the first humans, we have been telling stories. As we gathered around fires for warmth, stories became the vehicle by which we built relationships, entertained, derived meaning, and transmitted vital information to each other. Stories have always been how we make sense of the world. They are the operating system upon which human beings are programmed, informing how we organise our lives and societies and acting as the delivery agents of culture. Stories engage both our hearts and our minds, driving our behaviour in ways that are largely subconscious to us. They tell us who is a part of our tribe, and who is not. They tell us what is a normal and acceptable way to behave, and what sort of behaviours will see us being socially shunned. They prescribe the consequences that come from certain actions, and they teach us lessons.

At the very foundation of storytelling is language, and we cannot make use of language without framing. Frames are mental structures, ideas, or concepts that help us to make sense of the world around us. They are the cognitive shortcuts and metaphors that we use to provide instant context and information about any given matter. We use frames hundreds of times a day in everyday conversation, media, politics, education, and advertising. Slogans, taglines, and political catchcries rely on frames. The memes you see in your social media feeds rely on frames. They provide snapshots that in a microsecond draw on mental patterns, stereotypes, and heuristics (mental shortcuts) to provide meaning or understanding with just one or a handful of words.

Frames gain strength through repetition: the more we hear a certain frame, the more it becomes our accepted version of reality. Think of the term natural resources. Most of us use this phrase without a second thought, yet it implicitly suggests that the gifts of the natural world are there for humans to take and use. It doesn’t frame them as part of a whole complex living system or provide any clue that if we do in fact remove these “resources,” that the integrity of the living system suffers.

Through our choice of language, we are reinforcing a narrative of human dominance over nature. Consequently, we are heading down a path where we are consuming natural ecosystems on this planet as if we had another one to move to. When we are exposed to frames, they do not land on a blank slate. The readiness with which we accept or reject any given frame depends on many different factors. From the values and morals we hold most dear, to our relationships, beliefs, and early experiences of childhood, our minds are programmed to assess and categorise the information coming at us. We accept or ignore new information depending on how it is framed, and whether or not it fits with our pre-existing views about the world and how we see ourselves within it.

The most important and familiar part of storytelling, stories themselves, capture our hearts and minds from a young age. They are the conduits by which we gain understanding and find meaning. Usually we tell stories to serve or fulfil some predetermined purpose—to inspire, educate, entertain, inform, persuade, or manipulate. The word author is from the Latin word auctus, which translates literally to “one who causes to grow.” As such, our stories may sometimes take on a mythic quality with some sort of moral lesson or symbolic meaning attached, such as those that lie behind fables and parables.

Rhetoric

What is Rhetoric?

“Rhetoric may be defined as the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.” — Aristotle

Definition: Rhetoric is the art of using language effectively or persuasively.

Rhetoric is all around us. Rhetoric is in conversation, in movies, in advertisements, in books, in body language, and in art. We use rhetoric whether we’re conscious of it or not.

When we become conscious of how rhetoric works, we can transform speaking, reading, and writing – making us more effective communicators and more discerning audiences.

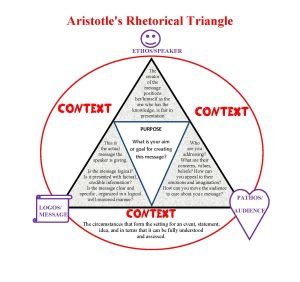

The Rhetorical Triangle: Subject, Audience, Speaker’s Persona

Aristotle believed that speakers could observe how communication happens from the world around them, and then use that understanding to develop sound and convincing arguments. In order to do this, speakers needed to look at three elements, graphically represented by what we now call the rhetorical triangle:

Aristotle said that when a rhetor (or speaker) begins to consider how to compose a speech— that is, begins the process of invention—the speaker must take into account three elements: the subject, the audience, and the speaker. The three elements are connected and interdependent; hence, the triangle.

1. The Subject:

Before I can communicate effectively, I must consider:

- What do we already know about this subject?

- What research is required for me to know more about this subject?

- Are there different perspectives regarding the subject?

- What types of evidence or proofs exist for these perspectives?

- Which proofs are useful for my argument?

- How do I support my claims with evidence?

But, Aristotle argued that knowing a subject is not sufficient for effective communication.

2. The Audience:

Examples of audience: a teacher, the audience of a play, the reader of a newspaper, a novel, a textbook

Before I can communicate effectively, I must:

- Speculate about audience expectations.

- Speculate about audience’s prior knowledge.

- Speculate about audience’s disposition.

In the classroom, your teachers will often spell out the audience’s expectation: “Write a five paragraph argumentative essay.” “State your thesis in the last sentence of the introductory paragraph.” “Use two outside sources.” “Have fun.”

However, when there is no fixed assignment, you must use experience and observation to imagine your audience in order to decide how best to communicate with that audience.

3. The Speaker’ Persona:

Writing is a form of imposture. “I’m not at all sure I am anything like the person I seem to a reader.” -E.B. White. (Merriam Webster: an instance of pretending to be someone else in order to deceive others.)

As I write, I create the character of the speaker. Aristotle called this the persona.

I use who I am, what I know and feel, what I have seen and done (my experience) to find my attitude toward the subject, and my understanding of the reader.

I create my persona – my speaking voice – through every decision I make in writing:

For example:

- Will I use formal or informal language?

- Will I use narration or quotations?

- Will my tone be familiar or objective?

The Appeals

Ethos: Mana

Together, he referred to ethos, logos, and pathos as the three modes of persuasion, or sometimes simply as “the appeals.” Aristotle believed that in order to have ethos a good speaker must demonstrate three things:

- Phronesis: Sound reasoning, and relevant experience or expertise.

- Arete: Moral character.

- Eunoia: Good intentions towards the audience.

Aristotle argued that a speaker in possession of these three attributes will naturally impress the audience with his or her ethos, and as a result will be better able to influence that audience. Over time, however, the definition of ethos has broadened, and the significance of the three qualities Aristotle named is now lost on anyone who hasn’t studied classical Greek. So it may give more insight into the meaning of ethos to translate Aristotle’s three categories into a new set of categories that make more sense in the modern era. A speaker or writer’s credibility can be said to rely on each of the following:

- Authority: A speaker in a high position of authority—for example, a president, or CEO—will possess a certain level of ethos simply because he or she can claim that title.

- Within literature, it’s interesting to notice when characters attempt to invoke their own authority and enhance their ethos by reminding other characters of the titles they possess. Often, this can be an indication that the character citing his or her own credentials actually feels his or her authority being threatened or challenged.

- Trustworthiness: Often, a large part of conveying trustworthiness to an audience depends on the speaker’s ability to demonstrate that he or she doesn’t have a vested interest in convincing the audience of his or her views. An audience should ideally feel that the speaker is impartial—doesn’t stand to gain anything personal, like money or power, from winning listeners’ favor—and that his or her opinions are therefore objective.

- In literature, this form of ethos is particularly relevant with respect to narrators. Authors often have their narrators profess impartiality or objectivity at the outset of a book in order to earn the reader’s trust in the narrator’s reliability regarding the story he or she is about to tell.

- Expertise: The credentials, education, and professional specialty of a speaker all greatly contribute to his or her ethos. For instance, a doctor’s assessment of a patient or a new drug will carry more weight with an audience than the opinion of someone with no medical training whatsoever.

- This type of ethos translates into literature quite easily, in the sense that characters’ opinions are often evaluated within the framework of their professions.

- Similarity: Speakers can strengthen their ethos by pointing out things that they share with an audience. This is a common technique in American politics where, for example, a candidate for office might describe his or her modest upbringing, in an effort to demonstrate that he or she is an average American and therefore shares the same values as voters. On the other hand, some speakers might find it more useful to convey that they are not like the audience and have a fresh, outside perspective. Either way, an important part of ethos is deciding whether to portray oneself as an insider or as an outsider to best make a point.

- Literary characters often use ethos to communicate similarity or likemindedness to other characters, and you can detect this by certain changes in their speech. In these situations, characters (as well as real-life speakers) often use a shibboleth—a specialized term or word used by a specific group of people—to show that they belong. For example, if you knew the name of a special chemical used to make jello, and you wanted to impress the head of a jello company, the name of that chemical would count as a shibboleth and saying it would help you show the jello executive that you’re “in the know.”

The Stagecraft of Ethos

In order to impress their positive personal qualities upon audiences, public speakers can use certain techniques that aren’t available to writers. These include:

- Speaking in a certain manner or even with a certain accent.

- Demonstrating confident stage presence.

- Having reputable people to introduce the speaker in a positive light.

- Listing their credentials and achievements.

Put another way, the ethos of a speech can be heavily impacted by the speaker’s confidence and manner of presenting him or herself.

Examples: Ethos

Politicians have always tried to connect ideas in every day life with their own agenda and narratives. Here are some examples from the world of political speeches.

t’s no secret a politician must be a master persuader. They have to earn the confidence of legions of people across a city or town, or even across a nation. One of the best ways to do that is to align their ethical code with the people they’re trying to elicit votes from. Let’s take a look at powerful orators who apply ethos to their speeches.

Barack Obama

In his speech in 2012, Barack Obama couldn’t be any more transparent in his use of ethos. He begins his speech by setting down his authority as a president and clarifying what he’s learned. You can see this through the excerpt.

“Now, the first time I addressed this convention, in 2004, I was a younger man — (laughter) — a Senate candidate from Illinois who spoke about hope, not blind optimism, not wishful thinking but hope in the face of difficulty, hope in the face of uncertainty, that dogged faith in the future which has pushed this nation forward even when the odds are great, even when the road is long.

Eight years later that hope has been tested by the cost of war, by one of the worst economic crises in history and by political gridlock that’s left us wondering whether it’s still even possible to tackle the challenges of our time. I know campaigns can seem small, even silly sometimes.”

Winston Churchill

Another great who was able to effectively use ethos in his speeches was Winston Churchill. In his 1941 address to the joint session, he establishes his credibility as a speaker. He shows the audience what he shares with common people. This excerpt works well to demonstrate his moral values.

“I may confess, however, that I do not feel quite like a fish out of water in a legislative assembly where English is spoken. I am a child of the House of Commons. I was brought up in my father’s house to believe in democracy. ‘Trust the people.’ That was his message. I used to see him cheered at meetings and in the streets by crowds of workingmen way back in those aristocratic Victorian days when as Disraeli said ‘the world was for the few, and for the very few.'”

Mitt Romney

When he accepted the Republican presidential nomination in 2012, Romney pointed to his business success as relevant experience that would serve him well if he were to take office:

“I learned the real lessons about how America works from experience.

When I was 37, I helped start a small company. My partners and I had been working for a company that was in the business of helping other businesses.

So some of us had this idea that if we really believed our advice was helping companies, we should invest in companies. We should bet on ourselves and on our advice.

So we started a new business called Bain Capital…That business we started with 10 people has now grown into a great American success story. Some of the companies we helped start are names you know. An office supply company called Staples – where I’m pleased to see the Obama campaign has been shopping; The Sports Authority, which became a favorite of my sons. We started an early childhood learning center called Bright Horizons that First Lady Michelle Obama rightly praised.”

Logos is an argument that appeals to an audience’s sense of logic or reason. For example, when a speaker cites scientific data, methodically walks through the line of reasoning behind their argument, or precisely recounts historical events relevant to their argument, he or she is using logos.

Logos: pārongo

Using logos as an appeal means reasoning with your audience, providing them with facts and statistics, or making historical and literal analogies:

- Aristotle defined logos as the “proof, or apparent proof, provided by the words of the speech itself.” In other words, logos rests in the actual written content of an argument.

- The three “modes of persuasion”—pathos, logos, and ethos—were originally defined by Aristotle.

- In contrast to logos’s appeal to reason, ethos is an appeal to the audience based on the speaker’s authority, while pathos is an appeal to the audience ‘s emotions.

- Data, facts, statistics, test results, and surveys can all strengthen the logos of a presentation.

Logos and Different Types of Proof

While it’s easy to spot a speaker using logos when he or she presents statistics or research results, numerical data is only one form that logos can take. Logos is any statement, sentence, or argument that attempts to persuade using facts, and these facts need not be the result of long research. “The facts” of an argument can also be drawn from the speaker’s own life or from the world at large, and presenting these examples to support one’s view is also a form of logos. Take this example from Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech in support of women’s rights:

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman?

Truth points to her own strength, as well as to the fact that she can perform physically tiring tasks just as well as a man, as proof of equality between the sexes: she’s still appealing to the audience’s reason, but instead of presenting abstract truths about reality or numerical evidence, she’s presenting the facts of her own experience as evidence. In this case, the logic of the argument is anecdotal (meaning it’s derived from a handful of personal experiences) rather than purely theoretical, but it goes to show that logos doesn’t have to be dry and clinical just because it’s concerned with proving something logically.

Logos: Proof vs. Apparent Proof

Not all speakers who use logos can be blindly trusted. As Aristotle specifies in his definition of the term, logos can be “proof, or apparent proof.” A speaker may present facts, figures, and research data simply to show that he or she has “done their homework,” in an effort to attain the degree of credibility that is often automatically attributed to scientific studies and evidence-driven arguments. Or a speaker might present facts in a way that is wholly or partially misrepresentative, using those facts (and, by extension, logos) to make a claim that feels credible while actually arguing something that is untrue. Yet another factor that can cause a speech or text to have the appearance of providing proof is the use of overlong words and technical language—but just because someone sounds smart doesn’t mean their argument stands to reason.

Even if the facts have been manipulated, any argument that relies on or even just claims to rely on “facts” to appeal to a listener’s reason is still an example of logos. Put another way: logos is not about using facts correctly or accurately, it’s about using facts in any way to influence an audience.

Examples: Logos

Politicians frequently use logos, often by citing statistics or examples, to persuade their listeners of the success or failure of policies, politicians, and ideologies.

Obama

In this example, Obama cites historical precedent and economic data from past years to strengthen his argument that recent progress has been substantial and that the nation’s economy is in good health:

But tonight, we turn the page. Tonight, after a breakthrough year for America, our economy is growing and creating jobs at the fastest pace since 1999. Our unemployment rate is now lower than it was before the financial crisis. More of our kids are graduating than ever before. More of our people are insured than ever before. And we are as free from the grip of foreign oil as we’ve been in almost 30 years.

Ronald Reagan

In this speech, Reagan intends for his comparison between the poverty of East Berlin—controlled by the Communists—and the prosperity of Democratic West Berlin to serve as hard evidence supporting the economic superiority of Western capitalism. The way he uses specific details about the physical landscape of West Berlin as proof of Western capitalist economic superiority is a form of logos:

Where four decades ago there was rubble, today in West Berlin there is the greatest industrial output of any city in Germany–busy office blocks, fine homes and apartments, proud avenues, and the spreading lawns of parkland. Where a city’s culture seemed to have been destroyed, today there are two great universities, orchestras and an opera, countless theaters, and museums. Where there was want, today there’s abundance–food, clothing, automobiles–the wonderful goods of the Ku’damm. From devastation, from utter ruin, you Berliners have, in freedom, rebuilt a city that once again ranks as one of the greatest on earth…In the 1950s, Khrushchev [leader of the communist Soviet Union] predicted: “We will bury you.” But in the West today, we see a free world that has achieved a level of prosperity and well-being unprecedented in all human history. In the Communist world, we see failure, technological backwardness, declining standards of health, even want of the most basic kind—too little food. Even today, the Soviet Union still cannot feed itself. After these four decades, then, there stands before the entire world one great and inescapable conclusion: Freedom leads to prosperity. Freedom replaces the ancient hatreds among the nations with comity and peace. Freedom is the victor.

Pathos: aurongo

Pathos is an argument that appeals to an audience’s emotions. When a speaker tells a personal story, presents an audience with a powerful visual image, or appeals to an audience’s sense of duty or purpose in order to influence listeners’ emotions in favor of adopting the speaker’s point of view, he or she is using pathos.

Some additional key details about pathos:

- You may also hear the word “pathos” used to mean “a quality that invokes sadness or pity,” as in the statement, “The actor’s performance was full of pathos.” However, this guide focuses specifically on the rhetorical technique of pathos used in literature and public speaking to persuade readers and listeners through an appeal to emotion.

- The three “modes of persuasion”—pathos, logos, and ethos—were originally defined by Aristotle.

- In contrast to pathos, which appeals to the listener’s emotions, logos appeals to the audience’s sense of reason, while ethos appeals to the audience based on the speaker’s authority.

- Although Aristotle developed the concept of pathos in the context of oratory and speechmaking, authors, poets, and advertisers also use pathos frequently.

Pathos in Depth

Aristotle (the ancient Greek philosopher and scientist) first defined pathos, along with logos and ethos, in his treatise on rhetoric, Ars Rhetorica. Together, he referred to pathos, logos, and ethos as the three modes of persuasion, or sometimes simply as “the appeals.” Aristotle defined pathos as “putting the audience in a certain frame of mind,” and argued that to achieve this task a speaker must truly know and understand his or her audience. For instance, in Ars Rhetorica, Aristotle describes the information a speaker needs to rile up a feeling of anger in his or her audience:

Take, for instance, the emotion of anger: here we must discover (1) what the state of mind of angry people is, (2) who the people are with whom they usually get angry, and (3) on what grounds they get angry with them. It is not enough to know one or even two of these points; unless we know all three, we shall be unable to arouse anger in any one.

Here, Aristotle articulates that it’s not enough to know the dominant emotions that move one’s listeners: you also need to have a deeper understanding of the listeners’ values, and how these values motivate their emotional responses to specific individuals and behaviors.

The philosopher and psychologist William James once said, “The emotions aren’t always immediately subject to reason, but they are always immediately subject to action.” Pathos is a powerful tool, enabling speakers to galvanize their listeners into action, or persuade them to support a desired cause. Speechwriters, politicians, and advertisers use pathos for precisely this reason: to influence their audience to a desired belief or action.

The use of pathos in literature is often different than in public speeches, since it’s less common for authors to try to directly influence their readers in the way politicians might try to influence their audiences. Rather, authors often employ pathos by having a character make use of it in their own speech. In doing so, the author may be giving the reader some insight into a character’s values, motives, or their perception of another character.

Pathos vs Logos and Ethos

Pathos is often criticized as being the least substantial or legitimate of the three persuasive modest. Arguments using logos appeal to listeners’ sense of reason through the presentation of facts and a well-structured argument. Meanwhile, arguments using ethos generally try to achieve credibility by relying on the speaker’s credentials and reputation. Therefore, both logos and ethos may seem more concrete—in the sense of being more evidence-based—than pathos, which “merely” appeals to listeners’ emotions. But people often forget that facts, statistics, credentials, and personal history can be easily manipulated or fabricated in order to win the confidence of an audience, while people at the same time underestimate the power and importance of being able to expertly direct the emotional current of an audience to win their allegiance or sympathy.

Examples: Pathos

Whenever someone tries to make you feel bad enough to do something, they’re using pathos as a rhetorical tool. They can also use pathos to explain how happy they would feel if you helped them out, or how hard it will be for them if you don’t.

Pathos examples in everyday life include:

- A teenager tries to convince his parents to buy him a new car by saying if they cared about their child’s safety they’d upgrade him.

- A man at the car dealership implores the salesman to offer the best price on a new car because he needs to support his young family.

- A boyfriend begs his girlfriend to stay with him, claiming “If you really love me, you’ll give me time to change my ways.”

- A car commercial depicts a teary-eyed parent saying goodbye to their child as they go off to college, sad but assured that they’re sending their child away in a reliable, safe car.

- Charity organizations show images of starving orphans living in dire conditions who need your help with monthly financial support.

Obama

In August 2013, the Syrian government, led by Bashar al-Assad, used chemical weapons against Syrians who opposed his regime, causing several countries—including the United States—to consider military intervention in the conflict. Obama’s tragic descriptions of civilians who died as a result of the attack are an example of pathos: they provoke an emotional response and help him mobilize American sentiment in favor of U.S. intervention.

Over the past two years, what began as a series of peaceful protests against the oppressive regime of Bashar al-Assad has turned into a brutal civil war. Over 100,000 people have been killed. Millions have fled the country…The situation profoundly changed, though, on August 21st, when Assad’s government gassed to death over 1,000 people, including hundreds of children. The images from this massacre are sickening: men, women, children lying in rows, killed by poison gas, others foaming at the mouth, gasping for breath, a father clutching his dead children, imploring them to get up and walk.

Reagan

In 1987, the Berlin Wall divided Communist East Berlin from Democratic West Berlin. The Wall was a symbol of the divide between the communist Soviet Union, or Eastern Bloc, and the Western Bloc which included the United States, NATO and its allies. The wall also split Berlin in two, obstructing one of Berlin’s most famous landmarks: the Brandenburg Gate.

Reagan’s speech, delivered to a crowd in front of the Brandenburg Gate, contains many examples of pathos:

Behind me stands a wall that encircles the free sectors of this city, part of a vast system of barriers that divides the entire continent of Europe…Yet it is here in Berlin where the wall emerges most clearly…Every man is a Berliner, forced to look upon a scar…

General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization: Come here to this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!

Reagan moves his listeners to feel outrage at the Wall’s existence by calling it a “scar.” He assures Germans that the world is invested in the city’s problems by telling the crowd that “Every man is a Berliner.” Finally, he excites and invigorates the listener by boldly daring Gorbachev, president of the Soviet Union, to “tear down this wall!”

In some classes this term (and each term following) you will be reading through some texts together. This is part of a wider reading programme that you will be required to follow throughout the term.

Here are some general questions for you to think about:

- What was your favorite part of the book?

- What was your least favorite?

- Did you race to the end, or was it more of a slow burn?

- Which scene has stuck with you the most?

- What did you think of the writing? …

- Did you reread any passages? …

- Would you want to read another book by this author?

You may also like to try using Reading Circles of five people. Each person is given one of the following roles and you can work through the story together.

- “The Leader” – facilitates the discussion, preparing some general questions and ensuring that everyone is involved and engaged.

- “The Summariser” – gives an outline of the plot, highlighting the key moments in the book. More confident readers can touch upon its strengths and weaknesses.

- “The Word Master” – selects vocabulary that may be new, unusual, or used in an interesting way.

- “The Passage Person” – selects and presents a passage from that they feel is well written, challenging, or of particular interest to the development of the plot, character, or theme.

- “The Connector” – draws upon all of the above and makes links between the story and wider world. This can be absolutely anything; books, films, newspaper articles, a photograph, a memory, or even a personal experience, it’s up to you. All it should do is highlight any similarities or differences and explain how it has brought about any changes in your understanding and perception of the book.

Here is the speech from Jacinda Ardern for the Memorial of the Christchurch Mosque Attack

Ko te reo te tuakiri | Language is my identity.

Ko te reo tōku ahurei | Language is my uniqueness.

Ko te reo te ora. | Language is life.