tohetohe

Be calm in arguing for fierceness makes error a fault and truth discourtesy.

– George Herbert

te ao Māori principles

There are five key principals that we as an English Department consider important as part of a holistic study at school. Please read through these and know that we will come back to them as we begin looking at texts.

- Kaitiakitanga: Guardianship of natural resources and elements of sustainability

- Rangatiratanga: Leadership, authority, Mana, empowerment, Respect

- Manaakitanga: The process of showing respect, generosity and care for others.

- Whanaungatanga: A relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides people with a sense of belonging.

- Tikanga: The customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in the social context.

Key Terms

|

harmony or accordance in opinion or feeling.

|

|

lack of consensus or approval.

|

|

a serious incompatibility between two or more opinions, principles, or interests.

|

|

a general agreement.

|

|

stated clearly and in detail, leaving no room for confusion or doubt.

|

|

suggested though not directly expressed.

|

|

think, understand, and form judgements logically. |

|

a set of reasons or a logical basis for a course of action or belief. |

|

showing or feeling active opposition or hostility towards someone or something. |

|

a heated argument or disagreement, typically about a trivial issue and between people who are usually on good term. |

|

provide evidence to support or prove the truth of. |

|

public support for or recommendation of a particular cause or policy. |

|

admit or agree that something is true after first denying or resisting it. |

|

the action of repeating something that has already been said or written. |

|

giving an authoritative command; peremptory. |

|

the arrangement of words and phrases to create well-formed sentences in a language. |

|

a word that can function as a noun phrase used by itself and that refers either to the participants in the discourse (e.g. I, you ) or to someone or something mentioned elsewhere in the discourse (e.g. she, it, this ) |

|

departing from a literal use of words; metaphorical. |

|

a word naming an attribute of a noun, such as sweet, red, or technical. |

|

an expression designed to call something to mind without mentioning it explicitly; an indirect or passing reference. |

|

a short amusing or interesting story about a real incident or person. |

|

a comparison between one thing and another, typically for the purpose of explanation or clarification. |

|

a sentence worded or expressed so as to elicit information. |

Learning Objectives

- To explain common misconceptions about the meaning of argument

- To describe defining features of argument

- To explain the logical structure of argument in terms of claim, reason, and assumption granted by the audience

- To describe the key elements of classical argument

- To explain the rhetorical appeals

- To read sources rhetorically by analyzing a text’s genre, purpose, and degree of advocacy

Exercises

Spelling

| revolution | establishment | impressive | condemn | retreat | text |

| acceptable | parallel | remark | era | surely | praise |

| commissioner | analysis | vessel | proud | inevitable | nerve |

| verdict | gentleman | tragedy | contemporary | consistent | everywhere |

| commander | agenda | resort | premium | fancy | margin |

Pangram

Remember, to become faster at writing, you should practise writing out the following phrase as many times as possible for 5 minutes.

- Fox dwarves chop my talking quiz job.

Reading Warm Up

Read the following passage.

| Professional baseball in the United States was for whites only until Branch Rickey hired Jackie Robinson. Because he is the first black major league baseball player, Robinson must rise above the insults hurled at him. He must prove by his play that he belongs on the Brooklyn Dodgers and that other African American athletes belong in the major leagues. He succeeds, and baseball teams become integrated. As the story begins, Branch Rickey decides that the time has come for blacks and whites to play together.

It was 1945, and World War II had ended. Americans of all races had died for their country. Yet black men were still not allowed in the major leagues. The national pastime was loved by all America, but the major leagues were for white men only. Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers thought that was wrong. He was the only team owner who believed blacks and whites should play together. Baseball, he felt, would become even more thrilling, and fans of all colors would swarm to his ballpark. Rickey decided his team would be the first to integrate. There were plenty of brilliant Negro league players, but he knew the first black major leaguer would need much more than athletic ability. But somehow this man had to rise above that. No matter what happened, he must never lose his temper. No matter what was said to him, he must never answer back. If he had even one fight, people might say integration would not work. At first Robinson thought Rickey wanted someone who was afraid to defend himself. But as they talked, he realized that in this case a truly brave man would have to avoid fighting. He thought for a while, then promised Rickey he would not fight back. Robinson signed with the Dodgers and went to play in the minors in 1946. Rickey was right— fans insulted him, and so did players. But he performed brilliantly and avoided fights. Then, in 1947, he came to the majors. On April 15—Opening Day—26,623 fans came out to Ebbets Field. More than half of them were black—Robinson was already their hero. Now he was making history just by being on the field. The afternoon was cold and wet, but no one left the ballpark. The Dodgers beat the Boston Braves, 5–3. Robinson went hitless, but the hometown fans didn’t seem to care—they cheered his every move. Yet through it all, he kept his promise to Rickey. No matter who insulted him, he never retaliated. Slowly his teammates accepted him, realizing that he was the spark that made them a winning team. No one was more daring on the base paths or better with the glove. At the plate, he had great bat control—he could hit the ball anywhere. That season, he was named baseball’s first Rookie of the Year. Jackie Robinson went on to a glorious career. But he did more than play the game well—his bravery taught Americans a lesson. Branch Rickey opened a door, and Jackie Robinson stepped through it, making sure it could never be closed again. Something wonderful happened to baseball—and America—the day Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers. |

Questions:

- Details can help you determine the author’s purpose, or main reason for writing. Underline one important detail in the opening passage. Write a question you can ask to understand the author’s purpose.

- What baseball team were Robinson and Rickey associated with?

- An expository essay is a short piece of nonfiction about a specific subject. What is the subject of this expository essay?

- How old was Jackie Robinson when he joined the team?

- Read the final sentence. How does this sentence help you understand the authors’ purpose in writing this essay?

- What did the St. Louis Cardinals threaten to do?

- Why do you think everyone eventually accepted him as a member of the team and how he helped integrate baseball?

- What is the purpose of this essay?

Listening Warm Up

In groups of 5 have a go at telling each other one thing from the following selection. You cannot repeat a starter phrase once it has been used. At the end your teacher will ask for a summary from the group.

- something funny that happened to me this week was…

- a place outside of Auckland that I have travelled to recently was…

- my favourite meal would have to be…

- if I was principal the first thing I would change about this school is…

- the last movie I went to see was…

Argument

Arguments are an important part of communication, and it shouldn’t be something that you get concerned about. We need to try and find ways to argue better, so that confrontation is not part of the equation, rather it is about the art of speaking and listening. Recognising that other people have different perspectives is a massive starting point for this whole topic.

It’s a massive topic, and we are only scratching the surface. Argumentation, when done correctly, will set you up for success in whatever you end up doing in your adult life. It will even greatly help your ability to write.

Remember: Not everyone will agree with everything we do, but the more we allow the view of others to inform our own, the better we all will end up.

The misconceptions of arguments

To many, the word argument connotes anger and hostility, as when we say, “I just got in a huge argument with my brother,” or “My mother and I argue all the time.” What we picture here is heated disagreement, rising pulse rates, and an urge to slam doors. Argument imagined as fight conjures images of shouting talk-show guests, flaming bloggers, or fist-banging speakers.

But to our way of thinking, argument doesn’t imply anger. In fact, arguing is often pleasurable. It is a creative and productive activity that engages us at high levels of inquiry and critical thinking, often in conversation with people we like and respect. For your primary image of argument, we invite you to think not of a shouting match on TV but of a small group of reasonable people seeking the best solution to a problem.

Not a Pro – Con Debate

Another popular image of argument is debate—a political debate, perhaps, or a high school debate tournament. According to one popular dictionary, debate is “a formal contest of argumentation in which two opposing teams defend and attack a given proposition.” Although formal debate can develop critical thinking, its weakness is that it can turn argument into a game of winners and losers rather than a process of cooperative inquiry.

As we explain throughout this site, argument entails a desire for truth; it aims to find the best solutions to complex problems. We don’t mean that arguers don’t passionately support their own points of view or expose weaknesses in views they find faulty. Instead, we mean that their goal isn’t to win a game but to find and promote the best belief or course of action.

Implicit or Explicit?

Before proceeding to some defining features of argument, we should note also that arguments can be either explicit or implicit. An explicit argument directly states its controversial claim and supports it with reasons and evidence. An implicit argument, in contrast, may not look like an argument at all. It may be a bumper sticker, a billboard, a poster, a photograph, a cartoon, a vanity license plate, a slogan on a T-shirt, an advertisement, a poem, or a song lyric. But like an explicit argument, it persuades its audience toward a certain point of view.

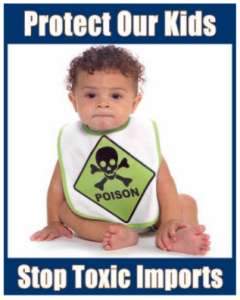

Have a look at this image

The photograph of the baby and bib makes the argumentative claim that baby products are poisonous; the photograph implicitly urges viewers to take action against phthalates. But this photograph is just one voice in a surprisingly complex conversation. Is the bib in fact poisonous?

Any argument, whether implicit or explicit, tries to influence the audience’s stance on an issue, moving the audience toward the arguer’s claim. Arguments work on us psychologically as well as cognitively, triggering emotions as well as thoughts and ideas.

Exercises

Have a look at the following images. For each one, answer the following questions:

- What bigger conversation does this argument join? By that I mean what is the issue or the controversy? What is at stake?

- What does the argument ‘claim’? That is, what value, perspective, belief or position does the argument ask its viewers to adopt?

- What is an opposing or alternative view? What views is the argument pushing against?

Extension

- Convert these implicit arguments in an explicit one by stating its claim and supporting reasons with words.

- How can implicit and explicit arguments work differently on the brains and hearts of the audience?

Other types of exchanges

Within the realm of communication there are any number of ways to connect or have conflict with another person. To begin with, we start with the easy stuff. We have agreement which is when two parts have a shared meaning or shared version of events. In this case, we have a consensus.

However, agreements don’t always happen in communication. So we then have the concept of disagreement. The use of the prefix ‘dis’ to mean ‘apart’ suggests that there is a lack of consensus.

A ‘quarrel’ is when two participants in a conversation exchange antagonistic or aggressive language towards each other without support or evidence.

An argument begins when there is some sort of evidence to support the assertions that are being made. Let’s take an example

Examples

Here is an exchange between a parent and a student.

| Student: | (racing towards the door putting a coat on) Bye! See you later! |

| Parent: | Whoa! Wait on there! What time are you planning on coming home? |

| Student: | (coolly) I told you before. I’ll be home at, like, 2am. |

| Parent: | (getting angry) We did not discuss this earlier and you are not staying out until two in the morning. You will be home at twelve. |

At this point we can see this is not an argument. This is a quarrel. There is no supporting evidence yet. If we never move on from ‘Yes-you-will / No-I-won’t’ then it will remain a quarrel. Or it could turn into a fight.

| Student: | But I am sixteen years old! |

No we are moving towards argument. Not a great one, not a well-developed one, but not we have a reason for the student’s assertion.

The parent can now either take that information and work with it (whether or not being sixteen means that there should be ownership of decisions like an appropriate time to return home) or return to quarreling. The parent will need to now use more evidence for their response to progress the argument.

So, we can establish that there are two conditions that we need to meet before we can call something an argument.

- a set of two or more conflicting assertions.

- the attempt to resolve the conflict through an appeal to reason.

But while the above meets those two conditions, it’s not a good argument. So we need to establish what constitutes a ‘good’ argument.

Argument is both a Process and a Product

As you can see above, an argument can be viewed as a process – that process being the exchange of ideas to seek the best solution to a question or problem. However, it can also be viewed as a product as in a person’s contribution (or side) to a conversation. Under formal settings such as a speech or presentation, the argument may be a position on a subject.

Similar elements occur in writing. A written argument such as a letter, an essay, an opinion piece in a newspaper, a review or a speech provide readers with a perspective on a given topic. In this case, sometimes it is other writers who will continue the exchange.

Argument Combines Truth Seeking and Persuasion

In considering argument as a product, the producer of the argument (speaker or writer) will often find themselves moving back and forth between truth seeking and persuasion, that is, between questions about the subject matter (what is the best solution to this problem?) and about audience (what do my audience already know, believe, or value?)

Different situations or contexts will provide a different set of requirements for arguments to be effective. Convincing parents will be different to convincing professors at university.

Reading argument rhetorically

As you read any given source connected to your issue, try to determine whether it is a background piece that provides the context for an issue, an overview article that tries to summarise the various positions in the controversy, or an argument that supports a position.

Questions for Reading Texts Rhetorically

- What genre of argument is this? How do the conventions of that genre help determine the depth, complexity, and even appearance of the argument?

- Who is the author? What are the author’s credentials and what is his or her investment in the issue?

- What audience is he or she writing for?

- What motivating occasion prompted the writing? The motivating occasion could be a current event, a crisis, pending legislation, a recently published alternative view, or another ongoing problem.

- What is the author’s purpose? The purpose could range from strong advocacy to inquiring truth seeker.

- What information about the publication or source (magazine, newspaper, advocacy Web site) helps explain the writer’s perspective or the structure and style of the argument?

- What is the writer’s angle of vision? By angle of vision, we mean the filter, lens, or selective seeing through which the writer is approaching the issue. What is left out from this argument? What does this author not see?

This rhetorical knowledge becomes important in helping you select a diversity of voices and genres of argument when you are exploring an issue.

Exercises

Find two recent arguments on the subject of minimum wage in New Zealand. You should find arguments from different genre (eg a letter, or a speech, or an article etc etc) and represent different kinds of arguers (a blogger, a scholar, etc). you can find your arguments online or in newspapers.

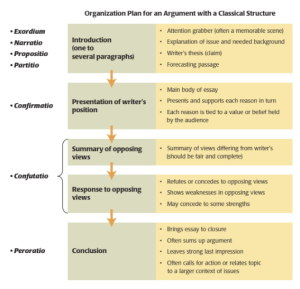

Classical Argument Structure

Classical argument is patterned after the persuasive speeches of ancient Greek and Roman orators. In traditional Latin terminology, the main parts of a persuasive speech are the exordium, in which the speaker gets the audience’s attention;

- the exordium, or ‘hook’, which catches the attention of the audience;

- the narratio, which provides needed background;

- the propositio, which is the speaker’s claim or thesis;

- the partitio, which forecasts the main parts of the speech;

- the confirmatio, which presents the speaker’s arguments supporting the claim;

- the confutatio, which summarizes and rebuts opposing views; and

- the peroratio, which concludes the speech by summing up the argument, calling for action, and leaving a strong, lasting impression.

Using Figurative Language

There are many many crossovers in English, something that you learn in one area of the course can definitely be used in another part.

It is the same in arguments. If you go back to your writing workshop section you can see how words, sentences and paragraphs can work here.

In writing using figurative language techniques, like metaphor and exaggeration you will find that these devices will help your argument.

The following ideas will also help

- Repetition: Repeating yourself so that you can reiterate an idea clearly and effectively

- Imperative: A command

- Syntax: The use of sentences to create meaning.

- Personal Pronoun: Making something more personal by using first person, or appealing to someone else by using second person

- Figurative Language: Creating images for the audience.

- Adjectives: Show comparatives and superlatives

- Rhetoric Devices: This is a new one, there are three main aspects to look at there.

- Allusion: making a reference to something that is well known, like ‘You’re Romeo and she’s Juliet’

- Anecdote: telling a personal story to help explain a point.

- Analogy: a comparison between one thing and another, typically for the purpose of explanation or clarification.

- Questions: Both rhetorical questions and direct questions can really help to explain something clearly.

In some classes this term (and each term following) you will be reading through some texts together. This is part of a wider reading programme that you will be required to follow throughout the term.

Each chapter will have some questions on books that you may like to think about. If your class is not studying a text, you may like to look at these questions yourself.

- What type of text is it? (ie novel, short stories, poems etc)

- What is the name of the book?

- What image is on the cover?

- Based on the name and the image on the cover, what do you think the book is about?

- How does the blurb add to your knowledge?

- What is the genre of the story? (ie action, romance, adventure)

After reading the first chapter

- From whose perspective is the story told?

- Who do you think is the main character?

- What do you learn in the first chapter?

You may also like to try using Reading Circles of five people. Each person is given one of the following roles and you can work through the story together.

- “The Leader” – facilitates the discussion, preparing some general questions and ensuring that everyone is involved and engaged.

- “The Summariser” – gives an outline of the plot, highlighting the key moments in the book. More confident readers can touch upon its strengths and weaknesses.

- “The Word Master” – selects vocabulary that may be new, unusual, or used in an interesting way.

- “The Passage Person” – selects and presents a passage from that they feel is well written, challenging, or of particular interest to the development of the plot, character, or theme.

- “The Connector” – draws upon all of the above and makes links between the story and wider world. This can be absolutely anything; books, films, newspaper articles, a photograph, a memory, or even a personal experience, it’s up to you. All it should do is highlight any similarities or differences and explain how it has brought about any changes in your understanding and perception of the book.

Dave Sumner on how to argue better

Ko te reo te tuakiri | Language is my identity.

Ko te reo tōku ahurei | Language is my uniqueness.

Ko te reo te ora. | Language is life.