meka riterite me te whakaaro

Beware of false knowledge. It is more dangerous than ignorance.

– George Bernard Shaw

te ao Māori principles

There are five key principals that we as an English Department consider important as part of a holistic study at school. Please read through these and know that we will come back to them as we begin looking at texts.

- Kaitiakitanga: Guardianship of natural resources and elements of sustainability

- Rangatiratanga: Leadership, authority, Mana, empowerment, Respect

- Manaakitanga: The process of showing respect, generosity and care for others.

- Whanaungatanga: A relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides people with a sense of belonging.

- Tikanga: The customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in the social context.

Key Terms

|

a thing that is known or proved to be true.

|

|

a view or judgement formed about something, not necessarily based on fact or knowledge. |

|

inclination or prejudice for or against one person or group, especially in a way considered to be unfair. |

|

the objective analysis and evaluation of an issue in order to form a judgement. |

|

the systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources in order to establish facts and reach new conclusions. |

|

the established set of attitudes held by someone. |

|

the time during which something is in use or operation. |

|

the quality or state of being closely connected or appropriate. |

|

the power to influence others, especially because of one’s commanding manner or one’s recognised knowledge about something. |

|

the quality or state of being correct or precise. |

|

the reason for which something is done or created or for which something exists. |

|

the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses. |

|

a set of reasons or a logical basis for a course of action or belief.

|

|

the ability to make considered decisions or come to sensible conclusions. |

Learning Objectives

- Explain the difference between fact, opinion and bias.

- Explore how critical thinking can affect meaning.

- Describe how fact and opinion can affect the understanding of a text.

- Show critical thinking skill from a text.

- Explore the mindset of the producer of a text.

- Show skepticism and curiosity in the interpretation of a text.

- Reflect on the student’s own thought process.

- Use evidence and reason to formulate decisions.

- Make judgments using evidence and reason.

Exercises

Spelling

| amendment | boost | entitle | acquisition | appoint | painful |

| rose | elegant | throat | expectation | fault | origin |

| belief | plate | carrier | electricity | appropriate | concession |

| corporation | stroke | intellectual | venture | reduction | presidency |

| regulation | broadcast | tube | atmosphere | phrase | adjust |

Pangram

Remember, to become faster at writing, you should practise writing out the following phrase as many times as possible for 5 minutes.

- Do wafting zephyrs quickly vex Jumbo?

Reading Warm Up

Read the following passage.

| Congressman Richard Durbin gave the following humorous speech in the House of Representatives on July 26, 1989. While most speeches to Congress are serious, Durbin’s is humorous yet persuasive and “drives home” the point that wooden baseball bats should not be replaced with metal ones.

Mr. Speaker, I rise to condemn the desecration of a great American symbol. No, I am not referring to flagburning; I am referring to the baseball bat. Several experts tell us that the wooden baseball bat is doomed to extinction, that major league baseball players will soon be standing at home plate with aluminum bats in their hands. Baseball fans have been forced to endure countless indignities by those who just can not leave well enough alone: designated hitters, plastic grass, uniforms that look like pajamas, chicken clowns dancing on the base lines, and, of course, the most heinous sacrilege, lights in Wrigley Field. Are we willing to hear the crack of a bat replaced by the dinky ping? Are we ready to see the Louisville Slugger replaced by the aluminum ping dinger? Is nothing sacred? Please do not tell me that wooden bats are too expensive, when players who cannot hit their weight are being paid more money than the President of the United States. Please do not try to sell me on the notion that these metal clubs will make better hitters. What will be next? Teflon baseballs? Radar-enhanced gloves? I ask you. I do not want to hear about saving trees. Any tree in America would gladly give its life for the glory of a day at home plate. I do not know if it will take a constitutional amendment to keep our baseball traditions alive, but if we forsake the great Americana of broken-bat singles and pine tar, we will have certainly lost our way as a nation. |

Questions:

- Why does the speaker wish to keep wooden baseball bats? Summarise his reasons.

- What is the author’s purpose in delivering this speech?

- How does the speaker use humorous images and language to appeal to the emotions of the audience?

- Does the sentence ‘metal bats should not replace wooden ones’ state the position of the author?

- Does the statement ‘baseball players make too much money’ support the author’s argument? Explain.

- Do you agree or disagree with Durbin’s argument?

- Provide at least two details from the speech that support your answer to question 6.

Listening Warm Up

In groups of 5 have a go at telling each other one thing from the following selection. You cannot repeat a starter phrase once it has been used. At the end your teacher will ask for a summary from the group.

- something funny that happened to me this week was…

- a place outside of Auckland that I have travelled to recently was…

- my favourite meal would have to be…

- if I was principal the first thing I would change about this school is…

- the last movie I went to see was…

Fact, Bias and Opinion

meka riterite me te whakaaro

Research

A major component of communication is the ability to speak with a level of authority. That is the case whether you are trying to convince others, sell a product, or just being part of a chat with others – either in real life or online.

It is therefore important to recognise the difference between fact and opinion, and where bias can come into play.

Check out https://zapatopi.net/treeoctopus/ to see the ability of websites to ‘look’ authentic, but have not basis in science.

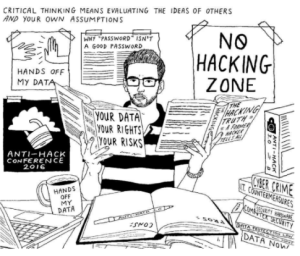

Critical Thinking

The term ‘critical thinking’ is used a lot, but not really explained well. A lot of definitions are confusing or just unclear in what it really means.

For the purposes of this text we need to agree on a definition:

- Critical thinking is the ability to think clearly and not take things at face value. Instead we question, analyse and evaluate what we read, hear, day or write.

Often the term critical thinker is given to people who have a way of thinking that fits with the above definition. Someone who asks questions to learn more and wants reliable information to make an informed decision.

Two prisoners are held in a dungeon. One night a mysterious visitor appears in their cell and offers them a chance to escape. It is only a chance because they must first reason to a decision which will determine whether or not they actually do go free.

Their cell is at the bottom of a long flight of steps. At the top is the outer door. Three envelopes, marked X, Y and Z, are placed on the table in the prisoners’ cell. One of them, they are told, contains the key to the outer door, but they may take only one envelope when they attempt to leave the cell. If they choose the wrong one, they will stay locked up forever, and the chance will not come again. It is an all-or-nothing decision. There are six clues, A to F, to help them – or puzzle them, depending on how you look at it. Two are printed on each envelope. There is also a general instruction, on a separate card, which stipulates:

No more than one of the statements on each envelope is false.

On envelope X it says:

A The jailhouse key is solid brass.

B The jailhouse key is not in this envelope.

On envelope Y it says:

C The jailhouse key is not in this envelope either.

D The jailhouse key is in envelope Z.

On envelope Z it says:

E The jailhouse key is solid silver.

F The jailhouse key is not in envelope X.

The prisoners may look inside the envelopes if they wish, before deciding. They have five minutes to make up their minds.

Decide which envelope the prisoners should choose in order to escape from the cell.

The best way to do this activity is to discuss it with a partner, just as the two prisoners would do in the story. As well as deciding which envelope to choose, answer this further question: Why is the envelope you have chosen the right one; and why can it not be either of the others?

Procedures and strategies

Procedures and strategies can help with puzzles and problems. These may be quite obvious; or you may find it hard even to know where to begin. One useful opening move is to look at the information and identify the parts that seem most relevant. At the same time you can write down other facts which emerge from them. Selecting and interpreting information in this way are two basic critical thinking and problem solving skills.

Start with the general claim, on the card, that:

[1] No more than one of the statements on each envelope is false.

This also tells you that:

[1a] At least one of the statements on each envelope must be true.

It also tells you that:

[1b] The statements on any one envelope cannot both be false.

Although [1a] says exactly the same as the card, it states it in a positive way rather than a negative one. Negative statements can be confusing to work with. A positive statement may express the information more practically. [1b] also says the same as the card, and although it is negative it restates it in a plainer way. Just rewording statements in this kind of way draws useful information from them, and helps you to organise your thoughts.

Now let’s look at the envelopes and ask what more we can learn from the clues on them. Here are some suggestions:

[2] Statements B and F are both true or both false (because they say the same thing).

[3] A and E cannot both be true. (You only have to look at them to see why.)

Taking these two points together, we can apply a useful technique known as ‘suppositional reasoning’. Don’t be alarmed by the name. You do this all the time. It just means asking questions that begin: ‘What if . . .?’ For example: ‘What if B and F were both false?’ Well, it would mean A and E would both have to be true, because (as we know from [1a]) at least one statement on each envelope has to be true. But, as we know from [3], A and E cannot both be true (because no key can be solid silver and solid brass).

Therefore:

[4] B and F have to be true: the key is not in envelope X: it is in either Y or Z.

This is a breakthrough. Now all the clues we need are on envelope Y. Using suppositional reasoning again we ask: What if the key were in Y? Well, then C and D would both be false. But we know (from [1b]) that they can’t both be false. Therefore the key must be in envelope Z.

Exercises

How strongly does the information in the article support the headline claim that the Wright brothers were not the first to fly?

- Answer this individually, or in a group or 2 or more. You are not expected to use any special terms or methods.

This is a typical critical thinking question, and one you will be asked in one form or another many times on different topics. This commentary will give you an idea, in quite basic terms, of the kind of critical responses you should be making.

Firstly, with any document, you need to be clear what it is saying, and what it is doing. We know from this article’s style that it is journalistic. But perhaps the most important point to make about it is that it is an argument. It is an attempt to persuade the reader that one of the most widely accepted stories of the 20th century is fundamentally wrong: the Wright brothers were not the first to fly a powered aeroplane. That claim is, as we have seen, made in the headline. It is echoed, though a bit more cautiously, in the caption beside the first photograph: ‘Or did they (make history)?’ The article then goes on to give, and briefly develop, four reasons to support the claim.

Two obvious questions need answering:

(a) whether the claims in the article are believable; and

(b) whether they support the headline claim. You cannot be expected to know whether or not the claims are true unless you have done some research. But it can be said with some confidence that they are believable. For one thing they could easily be checked.

As it happens, most if not all of the claims in the first four paragraphs are basically true.

- There are people who believe that Whitehead flew planes successfully before 1903. (You only need to look up Whitehead on the internet to see how many supporters he has.

- It is hard to say whether they count as ‘aviation experts’ or ‘historians’, but we can let that pass.)

- It is also true that Stella Randolf wrote books and articles in which she refers to numerous witnesses giving signed statements that they saw Whitehead flying.

- There really was a story in the New York Herald in 1901, reporting a half-mile flight by Whitehead, and quoting a witness as saying that the plane ‘worked perfectly’.

- The photograph of Whitehead with his ‘No. 21’ is understood to be genuine; and no one disputes that Whitehead built aircraft.

- It is a fact that Whitehead was a poor German immigrant.

- It is thought that the Smithsonian had some sort of agreement with the Wrights in return for their donating the Flyer.

If all these claims are so believable, is the headline believable too?

No single one of the claims would persuade anyone, but added together they do seem to carry some weight. That, however, is an illusion. Even collectively the evidence is inadequate. Not one of the claims is a first-hand record of a confirmed and dated Whitehead flight pre-1903. All the evidence consists of is a list of people who said that Whitehead flew. Author Jacey Dare reports that author Stella Randolf wrote that Louis Daravich said that he flew with Whitehead. Such evidence is inherently weak. It is what lawyers call ‘hearsay’ evidence, and in legal terms it counts for very little.

Here are three more negative points that you could have made, and quite probably did make.

- Firstly, the photograph of Whitehead’s plane does not show it in the air. The Wrights’ Flyer, by contrast, is doing exactly what its name implies: flying. ‘No. 21’ might have flown. (Apparently some ‘experts’ have concluded from its design that it was capable of flight.) But that is not the same as a photograph of it in flight; and had there been such a photograph, surely Jacey Dare would have used it in preference to one that shows the machine stationary and on the ground. The clear implication is that there is no photograph of a Whitehead machine airborne.

- Secondly, the New York Herald report is not a first-hand account: it quotes a single unnamed ‘witness’, but the reporter himself clearly was not there, or he would have given his own account.

- Thirdly Stella Randolf’s article and book were published 34 years after the alleged flight of ‘No. 21’, and the testimony of Louis Daravich was not made public until then either. Why? There are many possible reasons; but one, all-too-plausible reason is that it simply wasn’t true.

Mindset

Critical thinkers can be identified by the mindsets they have.

These could include being:

- inquisitive and curious, always seeking the truth

- fair in their evaluation of evidence and others’ views

- sceptical of information

- perceptive and able to make connections between ideas

- reflective and aware of their own thought processes

- open minded and willing to have their beliefs challenged

- using evidence and reason to formulate decisions

- able to formulate judgements with evidence and reason.

Critical Thinking Example

The following combination of letters represents a sentence from which one particular vowel has been removed. If you can figure out what that vowel is and re-insert it eleven times, in eleven different places, you will be able to determine what the sentence is saying.

VRYFINXMP

LARXCDSW

HATWXPCT

Most problem-solvers soon realize the missing letter is “e,” probably because the word “very” seems to jump out at them. They work very hard to construct the sentence with “very” as its first word. “Very” is not the first word, however; “every” is. When conviction and determination prevent us from exploring alternative options, we limit our potential for thinking critically. (The whole sentence reads, “Every fine exemplar exceeds what we expect.”)

Next:

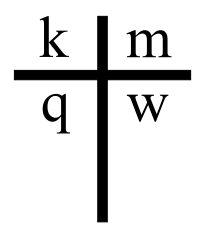

Have a look at the arrangement of the letters below. Which letter does not belong?

The letter “t,” which most people don’t even “see,” is out of place because it is bigger, thicker, and of a different color than the other letters.

You can see that while this is a silly exercise, it proves a point. We need to be mindful that sometimes that most obvious answer or the true answer isn’t the one that neither see, nor want.

The Speed Factor

More than ever we find that being slow or hesitant means that you’ll miss out. With increased frequency we are showing a reluctance to speed the world up. Typing is faster than handwriting. An email is faster than a letter. A message is faster than an email. And so on…

Speed is and of itself a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for critical thought. It must be supplemented with either creative or analytical thought – and sometimes with both. Hasty reactions can have disastrous results at both personal and corporate levels.

You may like to think of the stages as follows

What does this mean for oral language?

Oral language including public speeches relies on credible information and thorough research. Similarly, there are times in your school career when you will need to present researched information – especially later in the senior English classes when you need to quote supplementary (or supporting) research on a studied novel or poet.

To be effective as a speaker, or writer, you need to follow the expectations of critical thinking and the recognition of fact, bias, and opinion.

In critical thinking we use the same basic way of formalising arguments as logicians have used for many centuries: we list the reasons (or premises), and then the conclusion. If we use R for ‘reason’ and C for ‘conclusion’ we can say that all arguments have the form:

R1, R2, . . . Rn / C

The reasons and conclusion in a standard argument are all claims. In theory there is no limit to the number of reasons that can be given for a conclusion. In practice the number is usually between one and half-a-dozen.

The relation between the reasons and conclusion of standard argument is roughly equivalent to the phrase ‘so’, or ‘. . . and so . . .’, which is why inserting ‘so’ or ‘therefore’ into the text is a clue – though not an infallible one. What the whole argument states is that R1, R2, etc. are true; and that C follows from them. Or that because R1, R2, etc. are true, C must be true as well.

Consider the following examples. For each, think about how credible they are as arguments, and why:

- People shouldn’t be fooled into buying bottled mineral water. It’s meant to be safe but there have been several health alerts about chemicals found in some brands. It costs silly money, and anyway tap water, which is free, is just as good.

- It is inevitable that every year some athletes will give in to the temptation of taking performance-enhancing drugs. At the highest levels of sport, drugs can make the difference between winning gold and winning nothing. The rewards are so huge for those who reach the top that the risk will always seem worth taking.

- No sport should be allowed in which the prime object is to injure an opponent. Nor should any sport be allowed in which the spectators enjoy seeing competitors inflict physical harm on each other. On that score, boxing should be one of the first sports to be outlawed. What boxers have to do, in order to win matches, is to batter their opponents senseless in front of large, bloodthirsty crowds.

The C.R.A.A.P Test

CRAAP is an acronym for Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose. Use the CRAAP Test to evaluate your sources.

Currency: the timeliness of the information

- When was the information published or posted?

- Has the information been revised or updated?

- Is the information current or out-of date for your topic?

- Are the links functional?

Relevance: the importance of the information for your needs

- Does the information relate to your topic or answer your question?

- Who is the intended audience?

- Is the information at an appropriate level (i.e. not too elementary or advanced for your needs)?

- Have you looked at a variety of sources before determining this is one you will use?

- Would you be comfortable using this source for a research paper?

Authority: the source of the information

- Who is the author/publisher/source/sponsor?

- Are the author’s credentials or organizational affiliations given?

- What are the author’s credentials or organizational affiliations given?

- What are the author’s qualifications to write on the topic?

- Is there contact information, such as a publisher or e-mail address?

- Does the URL reveal anything about the author or source?

- examples:

- .com (commercial), .edu (educational), .gov (U.S. government)

- .org (nonprofit organization), or

- .net (network)

- examples:

Accuracy: the reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the content

- Where does the information come from?

- Is the information supported by evidence?

- Has the information been reviewed or refereed?

- Can you verify any of the information in another source or from personal knowledge?

- Does the language or tone seem biased and free of emotion?

- Are there spelling, grammar, or other typographical errors?

Purpose: the reason the information exists

- What is the purpose of the information? to inform? teach? sell? entertain? persuade?

- Do the authors/sponsors make their intentions or purpose clear?

- Is the information fact? opinion? propaganda?

- Does the point of view appear objective and impartial?

- Are there political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional, or personal biases?

In some classes this term (and each term following) you will be reading through some texts together. This is part of a wider reading programme that you will be required to follow throughout the term.

Each chapter will have some questions on books that you may like to think about. If your class is not studying a text, you may like to look at these questions yourself.

- What type of text is it? (ie novel, short stories, poems etc)

- What is the name of the book?

- What image is on the cover?

- Based on the name and the image on the cover, what do you think the book is about?

- How does the blurb add to your knowledge?

- What is the genre of the story? (ie action, romance, adventure)

After reading the first chapter

- From whose perspective is the story told?

- Who do you think is the main character?

- What do you learn in the first chapter?

You may also like to try using Reading Circles of five people. Each person is given one of the following roles and you can work through the story together.

- “The Leader” – facilitates the discussion, preparing some general questions and ensuring that everyone is involved and engaged.

- “The Summariser” – gives an outline of the plot, highlighting the key moments in the book. More confident readers can touch upon its strengths and weaknesses.

- “The Word Master” – selects vocabulary that may be new, unusual, or used in an interesting way.

- “The Passage Person” – selects and presents a passage from that they feel is well written, challenging, or of particular interest to the development of the plot, character, or theme.

- “The Connector” – draws upon all of the above and makes links between the story and wider world. This can be absolutely anything; books, films, newspaper articles, a photograph, a memory, or even a personal experience, it’s up to you. All it should do is highlight any similarities or differences and explain how it has brought about any changes in your understanding and perception of the book.

12 Cognitive Biases Explained

This is a fascinating overview of cognitive biases. It isn’t part of the course, but related to the ideas presented on this page. You may find it interesting.

Ko te reo te tuakiri | Language is my identity.

Ko te reo tōku ahurei | Language is my uniqueness.

Ko te reo te ora. | Language is life.