whakaataata

The smallest gestures you do can sometimes carry the most weight

– Joe Vitale

te ao Māori principles

There are five key principals that we as an English Department consider important as part of a holistic study at school. Please read through these and know that we will come back to them as we begin looking at texts.

- Kaitiakitanga: Guardianship of natural resources and elements of sustainability

- Rangatiratanga: Leadership, authority, Mana, empowerment, Respect

- Manaakitanga: The process of showing respect, generosity and care for others.

- Whanaungatanga: A relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides people with a sense of belonging.

- Tikanga: The customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in the social context.

Key Terms

|

any kind of delivery of written words recited aloud, including poetry readings, poetry slams, jazz poetry, and hip hop music, and can include comedy routines and prose monologues. |

|

the works of a particular author or artist that are recognized as genuine. |

|

the manner or style of giving a speech. |

|

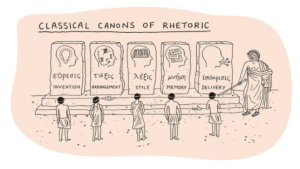

the art of effective or persuasive speaking or writing, especially the exploitation of figures of speech and other compositional techniques. |

|

quantity or power of sound; degree of loudness. |

|

a modulation of the voice expressing a particular feeling or mood. |

|

the quality of a sound governed by the rate of vibrations producing it; the degree of highness or lowness of a tone. |

|

enthusiasm, affection, or kindness. |

|

a shade of meaning. |

|

a quantity or amount considered in relation to or measured against another quantity or amount |

|

the formation of clear and distinct sounds in speech. |

|

a speech sound which is produced by comparatively open configuration of the vocal tract, with vibration of the vocal cords but without audible friction, and which is a unit of the sound system of a language that forms the nucleus of a syllable. |

|

a basic speech sound in which the breath is at least partly obstructed and which can be combined with a vowel to form a syllable. |

|

the way in which a word is pronounced. |

|

interrupt action or speech briefly. |

|

the state in which two people are aware of looking directly into one another’s eyes. |

|

a movement of part of the body, especially a hand or the head, to express an idea or meaning. |

|

lay stress on (a word or phrase) when speaking. |

|

an absurdly exaggerated piece of behaviour. |

|

an act of showing that something exists or is true by giving proof or evidence. |

|

hand movements that accompany speech and allow the speaker to effectively communicate thoughts. |

|

qualities, actions, or things are connected with a person’s body, rather than with their mind. |

|

walk at a steady speed, especially without a particular destination and as an expression of anxiety or annoyance. |

|

the branch of knowledge that deals with the amount of space that people feel it necessary to set between themselves and others. |

|

a continuous area or expanse which is free, available, or unoccupied. |

|

the length of the space between two points. |

|

an impression given by someone or something. |

|

the quality of being trusted and believed in. |

Learning Objectives

- Incorporate appropriate gesture to support the meaning of a speech.

- Develop vocal and non vocal techniques in public speaking.

- Practice speaking in front of others.

- Develop self confidence through multiple exposure to speaking opportunities.

- Listen to others.

- Provide feedback and take on feedback from others.

Exercises

Spelling

| existing | jewellery | conventional | electoral | consist | missile |

| opposite | absolute | regulator | referendum | combination | pleasant |

| fabric | congressional | mask | consciousness | equity | meal |

| conscious | concentration | vital | theme | illegal | honest |

| cue | plot | collective | numerous | licence | mutual |

Pangram

Remember, to become faster at writing, you should practise writing out the following phrase as many times as possible for 5 minutes.

- My ex pub quiz crowd gave joyful thanks.

Reading Warm Up

Read the following passage.

| This text is an online article giving advice from the editor of a website to people thinking of a career in travel writing.

‘Don’t worry,’ said the stallholder. ‘The snake round your daughter’s neck is not venomous.’ That was the example my instructor used when he taught us the immense value of a good opening to an article. My instructor is the travel editor for a national newspaper. Since 2000, he has written about, and been hopelessly lost in, diverse destinations on six continents. Having quit my job in software design to become a travel blogger and edit this website, I was attending a travel writing conference he was running. I wanted to improve the writing on my blog; my writing has improved, but I didn’t anticipate how much that conference would affect my role as an editor. If you have sent me an article and I have rejected it, it was probably because of something I learned at that conference. Writers of the unsuccessful articles submitted to me seem to think that they need extra padding at the beginning that goes something like: ‘Travel is wonderful. We should all travel.’ Get to the point. The articles I hate the most begin: ‘Our plane landed in ’. If the most interesting portion of your trip is the plane landing and collecting your luggage, then OK, start your story that way. Arguably though, if this really is the most interesting portion of your trip, you’d be better off staying at home. Good travel writing transports people. It celebrates the differences in manners and customs around the world, helping readers to understand other people and places. It helps readers plan their own trips and avoid costly mistakes while travelling. Most of all, readers get to experience those far-off destinations that they may never visit. I should point out, while I’m encouraging others to pursue their career in travel writing, that it was also at that conference that I decided to return to working in software design. Sitting in a room full of travel writers who were describing how difficult it is to make a living persuaded me to keep it strictly as a hobby. But if you have the desire to travel, and the savings, I can recommend that annual conference which my good friend runs every August. |

Questions:

- Give the example used by the instructor to teach the value of a good opening to an article, according to the text.

- Using your own words, explain what the text means by: ‘immense value’ (paragraph 2) and ‘diverse destinations’ (paragraph 2)

- Give two ways in which attending the conference changed the writer

- Re-read paragraphs 4 and 5 (‘Writers of never visit.’).

- Identify two mistakes made by writers of unsuccessful articles

- Explain why people like to read good travel writing, according to the text

- ) Re-read paragraphs 6 and 7 (‘I should point out every August.’). Using your own words, explain why people might not accept the writer’s advice about being a travel writer

Listening Warm Up

In groups of 5 have a go at telling each other one thing from the following selection. You cannot repeat a starter phrase once it has been used. At the end your teacher will ask for a summary from the group.

- something funny that happened to me this week was…

- a place outside of Auckland that I have travelled to recently was…

- my favourite meal would have to be…

- if I was principal the first thing I would change about this school is…

- the last movie I went to see was…

Dramatic Techniques

whakaataata

Public Speaking Emphasizes the Spoken Word. Any speaker can supplement her or his speech with pictures, charts, videos, handouts, objects, or even a live demonstration. However, public speakers devote most of their time to speaking to their audience. The spoken word plays the central role in their message, although speakers use gestures, posture, voice intonation, eye contact, other types of body language, and even presentation aids to heighten the effect of their words.

We have looked closely at words and putting them together, now we need to look at how other aspects can add to a message.

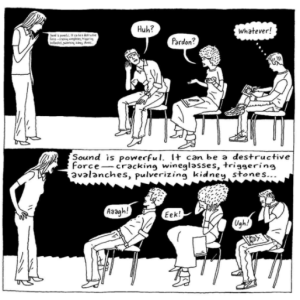

Remember that any speech is still a two way communication. As you deliver your speech, pay attention to factors you can control that affect your audience’s ability to listen—voice, volume, fluency, projection, rate, and timing. Speaking too quietly can inhibit listening, as can poor fluency, fast delivery, or excessive pausing. Be sure to maintain eye contact with your audience, and avoid making obtrusive gestures (such as pointing at the audience) or turning your back on the group while adjusting a visual aid.

Voice Techniques

- Volume

Volume refers to how loud or soft your voice is as you deliver a speech. Some speakers are not audible enough, and others are too audible. A guiding rule for volume is to be loud enough so that everyone in your audience can hear you but not so loud as to drive away the listeners positioned closest to you.

The biggest challenge for many presenters is speaking loudly enough to be heard. Because audience members don’t have the option of “turning up the volume,” you will need to provide that volume yourself when no microphone is available. If you speak too softly and don’t project enough, your listeners may have trouble hearing you. They may even see you as timid or uncertain—which could damage your credibility.

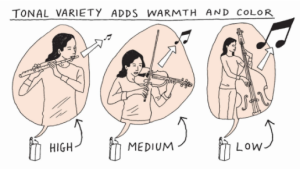

- Tone

The tone of your speaking voice derives from pitch—the highs and lows in your voice. If you can mix high and low tones and achieve some tonal variety, you’ll add warmth and color to your verbal delivery. By contrast, if your tone never varies (speaking in a monotone), listeners may perceive your presentation as bland, boring, or even annoying (in the case of a relentlessly high-pitched voice).

How much tonal variety should you aim for to make your voice interesting and enticing? Follow this guiding rule: use enough tonal variety to add warmth, intensity, and enthusiasm to your voice but not so much variety that you sound like a primary student. As you practice your speech, try dropping your pitch in some places and raising it in others. If you’re not sure whether you’re achieving enough tonal variety, practice in front of a trusted friend, family member, classmate, or colleague, and solicit her or his feedback.

Additionally, consider using inflection—raising or lowering your pitch —to emphasize certain words or expressions. For instance, try a lower pitch to convey the seriousness of an idea, or end on a higher pitch if you are posing a question. Like italics on a printed page, inflection draws attention to the words or expressions you want your audience to notice and remember.

- Rate of Delivery

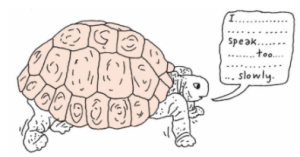

Your rate of delivery refers to how quickly or slowly you speak during a presentation. As with other verbal delivery skills, going to one extreme or another (in this case, speaking too quickly or too slowly) can hurt your delivery.

Do you fall into the “slow speaker” category? Do people tend to finish your sentences for you—during conversations or while you’re delivering a public address? Although people who try to finish your statements may seem rude, their behavior sends an important signal that you need to increase your rate of delivery. Fail to catch that signal, and you risk losing your audience’s interest and appreciation.

Swinging to the other extreme—talking too fast—presents the opposite problem. Overly fast talkers tend to run their words together, particularly at the ends of sentences, preventing their audiences from tracking what they’re saying. Listeners often have a difficult time in this situation—not because they are disinterested or impatient but simply because they cannot comprehend what is being said. In the worst-case scenario, potentially interested audience members may transform into defeated listeners because of a fast talker’s too-quick delivery.

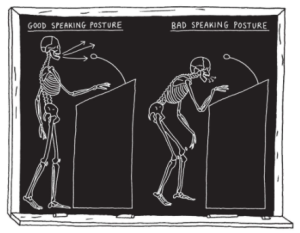

Have you ever observed someone singing without a microphone and wondered how the person’s voice managed to reach people near and far? What about actors on a stage who speak their lines quietly yet can still be heard by everyone in the theater? These individuals use projection— “booming” their voices across a forum to reach all audience members. To project, use the air you exhale from your lungs to carry the sound of your voice across the room or auditorium. Projection is all about the mechanics of breathing. To send your voice clearly across a large space, first maintain good posture: sit or stand up straight, with your shoulders back and your head at a neutral position (not too far forward or back). Also, exhale from your diaphragm—that sheet of muscle just below your rib cage—to push your breath away from you.

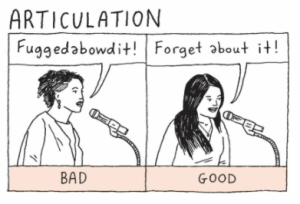

- Articulation

Articulation refers to the crispness or clarity of your spoken words. When you articulate, your vowels and consonants sound clear and distinct, and your listeners can distinguish your separate words as well as the syllables in your words. The result? Your audience can easily understand what you’re saying.

Articulation problems are most common when nervousness increases a speaker’s rate of delivery or when a speaker is being inattentive. Whatever the cause of your articulation issues, focus on this rule to get better results: when you deliver a speech, clearly and distinctly express all parts of the words in your presentation, and make sure not to round off the ends of words or lower your voice at the ends of sentences.

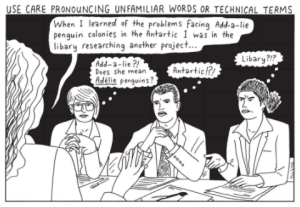

- Pronunciation

Pronunciation refers to correctness in the way you say words. Are you saying them in a way that has been commonly agreed to? If you pronounce terms incorrectly, your listeners may have difficulty understanding you. Equally troublesome, they may question your credibility.

How can you ensure that your pronunciation is accurate? The guideline here is simple: if you’re not certain how to pronounce a word or a name you want to use in your speech, find out how to say it before you deliver your presentation. For names of public figures, search for radio or television interviews with the subject to find out the preferred pronunciation. For other words, you can ask for guidance from your instructors, classmates, coworkers, or friends who might be familiar with the term. Better still, refer to a reputable dictionary, which will provide phonetic spellings for each word as well as a general guide to pronunciation. Many online dictionaries and other resources provide useful audio clips that demonstrate proper pronunciation.

- Pausing

Used skillfully, pausing—leaving gaps between words or sentences in a speech—provides you with some significant advantages. Besides enabling you to collect your thoughts, it reinforces the seriousness of your subject because it shows that you’re choosing your words carefully. Pausing can help you create a sense of importance as well. If you make a statement and then pause for the audience to weigh your words, your listeners may conclude that you’ve just said something especially important.

To get the most from pausing, use it judiciously, pausing every so often rather than after every sentence. Otherwise, your listeners may wonder if you’re having repeated difficulty collecting your thoughts, or they may think you’re being melodramatic. In either case, your audience will begin to take you less seriously.

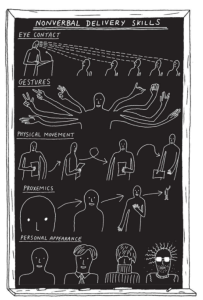

Non Voice Techniques

- Eye Contact

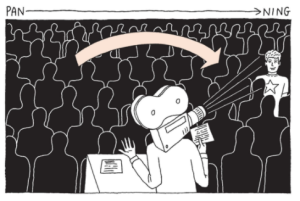

To understand what eye contact is, you may find it helpful to think first about what it is not. Eye contact is not you looking at your audience members while they look at something else. Nor is it audience members looking directly at you while you stare at your notes or nervously gaze at the ceiling for some divine guidance on what to say next. Rather, with true eye contact, you look directly into the eyes of your audience members, and they look directly into yours.

Eye contact enables you to gauge the audience’s interest in your speech. By looking into your listeners’ eyes, you can discern how they’re feeling about the speech (fascinated? confused? upset?). Armed with these impressions, you can adapt your delivery if needed. For example, you could provide more details about a particular point if your listeners look fascinated and hungry for more or reexplain a key point if your listeners look confused or overwhelmed.

Eye contact also helps you interact with your audience. By glancing at a particular listener, for instance, and noticing that he or she seems eager to ask a question, you might be prompted to stop and take queries from the audience.

Finally, eye contact helps you compel your audience’s attention. When you and your audience establish eye contact, it becomes difficult for listeners to look away or mentally drift as you’re talking.

From the audience’s perspective, eye contact is critical for another reason entirely. In Western cultures, many people consider a willingness to make eye contact evidence of a speaker’s credibility—especially truthfulness.

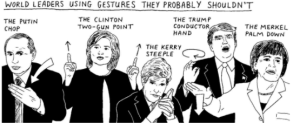

- Gestures

A gesture is a hand, head, or face movement that emphasizes, pantomimes, demonstrates, or calls attention to something.

Gestures can add flair to your speech delivery, especially when they seem natural rather than overly practiced. Research also indicates that gestures can benefit a listener’s ability to understand a speech’s message.

The effectiveness of a gesture depends on how it links with the speech topic—so gestures depicting physical actions communicate more than those depicting abstract topics. Hand gestures that link with speech content are called co-speech gestures (CSGs). CSGs communicate thoughts and ideas in two different ways—linguistically (through words that are heard) and visually (through the gesture that is seen). Neuroimaging of the brain shows that when CSGs are used with speech, there is more activity in the parts of the brain involved with language processing—meaning that listeners understand and retain more.

- Physical Movement

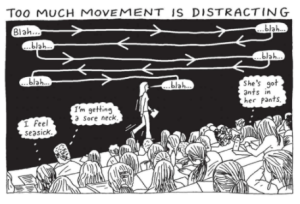

Physical movement describes how much or how little you move around while delivering a speech. Not surprisingly, standing still (sometimes referred to as the “tree trunk” approach) and shifting or walking restlessly from side to side or back and forth (“pacing”) in front of your audience are not effective. A motionless speaker comes across as boring or odd, and a restless one is distracting and annoying.

Instead of going to either of these extremes, strive to incorporate a reasonable amount and variety of physical movement as you give your presentation. Skillful use of physical movement injects energy into your delivery and signals transitions between parts of your speech. For example, when making an important point in your presentation, you can take a few steps to the left in front of your audience and casually walk back to your original spot when you shift to the next major idea. One useful tip is to combine moderate movement with the panning approach to eye contact, discussed earlier in this section.

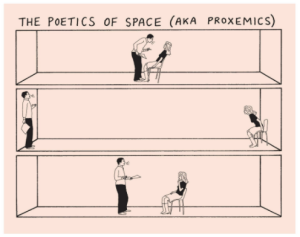

- Proxemics

Proxemics—the use of space and distance between yourself and your audience—is related to physical movement. Through proxemics, you control how close you stand to your audience while delivering your speech.

The size and setup of the speech setting can help you determine how best to use proxemics. For example, in a large forum, you may want to come out from behind the podium and move closer to your audience so that listeners can see and hear you more easily. Moving toward your audience also can help you communicate intimacy; it suggests you’re about to convey something personal, which many audience members will find compelling. Research has shown that audiences perceive a strong association not only between closeness and intimacy but also between closeness and attraction and that they see closeness as an indication of the immediacy/non immediacy of the speech message.

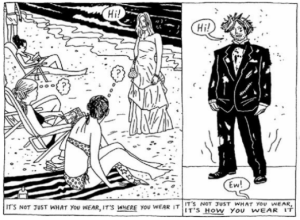

- Personal Appearance

By personal appearance, we refer to the impression you make on your audience through your clothing, jewelry, hairstyle, and grooming, and other elements influencing how you look.

Personal appearance in a public speech matters for two reasons. First, many people in your audience will form their initial impression of you before you say anything—just by looking at you. Be sure your appearance communicates the right message. Second, studies show that this initial impression can be long lasting and very significant.

If you make a negative first impression because of a sloppy or an otherwise unappealing appearance, you’ll need to expend a lot of time and effort to win back your audience’s trust and rebuild your credibility.

In some classes this term (and each term following) you will be reading through some texts together. This is part of a wider reading programme that you will be required to follow throughout the term.

Each chapter will have some questions on books that you may like to think about. If your class is not studying a text, you may like to look at these questions yourself.

- What type of text is it? (ie novel, short stories, poems etc)

- What is the name of the book?

- What image is on the cover?

- Based on the name and the image on the cover, what do you think the book is about?

- How does the blurb add to your knowledge?

- What is the genre of the story? (ie action, romance, adventure)

After reading the first chapter

- From whose perspective is the story told?

- Who do you think is the main character?

- What do you learn in the first chapter?

You may also like to try using Reading Circles of five people. Each person is given one of the following roles and you can work through the story together.

- “The Leader” – facilitates the discussion, preparing some general questions and ensuring that everyone is involved and engaged.

- “The Summariser” – gives an outline of the plot, highlighting the key moments in the book. More confident readers can touch upon its strengths and weaknesses.

- “The Word Master” – selects vocabulary that may be new, unusual, or used in an interesting way.

- “The Passage Person” – selects and presents a passage from that they feel is well written, challenging, or of particular interest to the development of the plot, character, or theme.

- “The Connector” – draws upon all of the above and makes links between the story and wider world. This can be absolutely anything; books, films, newspaper articles, a photograph, a memory, or even a personal experience, it’s up to you. All it should do is highlight any similarities or differences and explain how it has brought about any changes in your understanding and perception of the book.

Breathing

Breathing. It is really important to breathe correctly to help with your stress levels and preparation for the speech.

Ko te reo te tuakiri | Language is my identity.

Ko te reo tōku ahurei | Language is my uniqueness.

Ko te reo te ora. | Language is life.