Acknowledgements

Necessity of Acknowledging Context

This is a book on community and organizational change, so knowing and acknowledging the context of my work feels important and relevant. So much of the context for community work includes tragic history and the strengths and resilience of the people who have survived unthinkable intentional acts at the hands of oppressors who abused their power often for hundreds of years. It is baked into the fabric of our communities and incorporated into the DNA of our children. My community is no exception, so it needs to be acknowledged. If ignored, because it is too hard to hear, then expect to be less effective in your work. Period.

As I am a settler in the region where I live and work, there are a few critical place-based and people-based acknowledgments that I need to make in order to provide some context for this text.

My Community

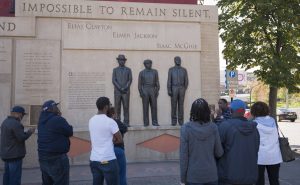

These images reflect the beauty of the community that I call ‘home.’ It is rich with stories, recent and past, and filled with people who are active in creating the community that they want to live in—one in which they feel welcomed and able to thrive and lead.

Region as Home to the Anishinaabe

I am writing this book from the shores of Lake Superior, in a region that is the current home to the Anishinaabe people[1]. Specifically, we are located in the treaty-ceded territory of the 11 Ojibwe Tribes of Minnesota and Wisconsin. As identified in the treaties, particularly from 1854, the Nations ceded the land in northern Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, but retained the rights to hunt, fish, and gather in the ceded territories[2]. This agreement must be honored and remains critical to health and healing.

This knowledge is critical for any of us who work or live in the Upper Midwest, as it helps us to understand the life-giving Manoomin (wild rice); the enormous cost of the tragedy of the Sandy Lake Massacre, and the horrifying actions preceding the massacre; the legacy of the boarding school era on families and communities; the reality of missing and murdered Indigenous people; the necessity of food sovereignty; the ingenuity of culturally-relevant human service strategies; the importance of language revitalization as empowerment and resilience, and so much more.

Region as Site of Community Violence

I am also writing this book from a community that engaged in an incident of lynching during the Jim Crow era of three African American men over 100 years ago[3]. A mob of 6-10,000 people came together in a matter of hours to murder three African American men who were in Duluth, Minnesota with a traveling circus. Clearly, the circumstances of hate and tension already existed when the men were wrongly accused of raping a white woman was made. Just think….the mob was gathered primarily by word-of-mouth as people drove around the city exclaiming that they needed to take justice into their own hands.

Often people are very surprised to know that this occurred in such a Northern state, far from the Jim Crow South. This is a part of the myth of the progressive North.

So. . . what is the history of your community that shapes the context for your work?

My Help and Inspiration

In addition, I want to recognize some of the people who have individually assisted or inspired my work. This includes former social work students like Vanessa Sowl, who read through this text and provided critical honest feedback; my amazing niece, Kate, who worked most closely with me to edit the entire text; Jax Kobielus, the technically talented and very kind copy editor at UW-Superior who edited and polished the entire draft; my closest friends—Emily, Patty, Shari, Dana, Sandra, Erik, Kevin— who were endlessly encouraging; more friends, community organizers and mentors like Carl Crawford, LeAnn Littlewolf, Nevada Littlewolf, Ivy Vainio, Treasure Jenkins, Emma Carroll, Henry Banks, Steve O’Neil, Erik Peterson, Denny Falk and many more who I have learned from and been challenged by in necessary ways over the years; amazing coworkers at UW-Superior (Mimi, Mandy, Cherie, Haji, T, Laurel, Kennedy, Salisa, Stephanie, Emily, Travis, Del, Rachel, Ina…), all the amazing changemakers at Ashoka who I recently became connected with and of course my family—Mom (Kathy), Brother (Richard), Eric, Ian, Cy, and Cal. It wasn’t important that they understood what I was working on, but I did need the encouragement and space for me to do my ‘thing.’

Finally, I am inspired by the youth! All change-making efforts should keep youth at the center of our work. We have an opportunity and responsibility to shape the world in which they can be their authentic selves and live out the dreams they have for themselves and their families.