25 Selecting and Defining the Interventions

The group of people who are leading the community planning process, are often referred to as the Core Leadership Team, also needs to identify the criteria for evaluating potential interventions. This is the team that has been working on this community change project from the beginning and is more aware of the context behind the project than the general public. The criteria should be based upon the root causes of the issue or situation you are attempting to address and has to be grounded in the needs, goals, and ideas shared by the community stakeholders.

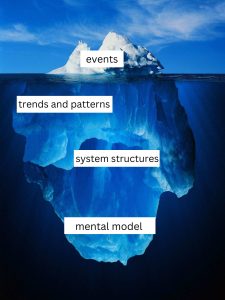

These root causes were identified through the systems thinking process of analyzing the community’s needs, as described through the iceberg metaphor.

Prevention vs Response Interventions

The most effective interventions are those that focus on leverage points, using minimal resources for long-term effects. These leverage points are focused on the systemic structures that demonstrate the cause of the symptoms, evidence, or events. These interventions are typically considered preventative in nature. Stroh (2015) calls these ‘high-level interventions’[1]. The most powerful interventions are going to be preventative in nature because they reduce or eliminate the risks that come from unaddressed symptoms that will likely get worse. Prevention saves lives, saves money, and is empowering.

A common way to explain the need for prevention and response is with the principle of “upstream.”

A familiar method for explaining this uses the imagery of a river, as shown in the graphic, “Social Determinants and Social Needs: Moving Beyond MIdstream”.[2] Imagine you are standing on the side of the river, likely minding your own business, when you see someone in front of you in crisis. They are struggling to survive in the water. If you don’t do something, they may not make it. You pull that person out and get them to safety, providing them warmth, dry clothes, etc. You essentially save them and treat their symptoms. Unfortunately, this keeps happening and you cannot move from your place at the side of the river where person after person needs your immediate help. This is a crisis that appears not to have an end. However, to end the crisis means that someone—you or someone else—needs to travel ‘upstream’ to see why people are falling into the river in the first place.

A familiar method for explaining this uses the imagery of a river, as shown in the graphic, “Social Determinants and Social Needs: Moving Beyond MIdstream”.[2] Imagine you are standing on the side of the river, likely minding your own business, when you see someone in front of you in crisis. They are struggling to survive in the water. If you don’t do something, they may not make it. You pull that person out and get them to safety, providing them warmth, dry clothes, etc. You essentially save them and treat their symptoms. Unfortunately, this keeps happening and you cannot move from your place at the side of the river where person after person needs your immediate help. This is a crisis that appears not to have an end. However, to end the crisis means that someone—you or someone else—needs to travel ‘upstream’ to see why people are falling into the river in the first place.

What is the cause of the crisis? What system is failing all of these people? What assumptions or mindsets are influencing people to enter the river or throwing them into the river? In order to address the crisis downstream, you have to address the causes and prevent the crisis from occurring in the first place.

In the area of mental health and well-being, a list of brainstormed ‘upstream’ or preventative interventions could include any of the following strategies:

- Mindfulness skills and practice

- Support groups

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) skill development for all youth

- Wellness and recovery planning

- Opportunities to be in healing spaces, like outdoors or inside nurturing spaces

- De-escalation training for first responders

- Coping mechanism development

- Social-emotional learning in schools

- Wraparound support for families

- Encouraging outside play, sports, and hobbies

- Annual mental health check-ups

- Integrating primary and mental health care

- Ending stigma

These are the types of ideas that may address some of the underlying or root causes of mental health crises. There are also models for us to use or reference which help point us in the direction of prevention vs response interventions. One of these models applied widely in community change work related to health is the Social Determinants of Health.

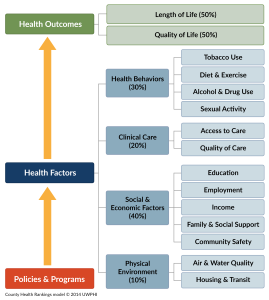

Example: Social Determinants of Health

The social determinants of health model, established by the University of Wisconsin’s Population Health Initiative, is an excellent explanation of the various factors that impact a person’s health. It includes factors that are commonly attributed to health and therefore receive an enormous amount of investment, which is clinical health care. What this model demonstrates, however, is that social and economic factors (employment, income, family and social support, and community safety) have an even greater impact on overall health than clinical care. This can help identify the interventions at the ‘leverage points’ for the greatest impact[3].

Selecting the Wow interventions

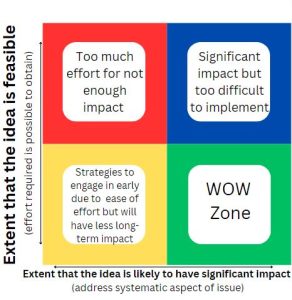

One way to select the community change strategy intervention is to ask, What wows? Once there is a significant list of brainstormed ideas, and there are criteria established for the factors most likely to positively impact the issue, you now have the opportunity to select the intervention(s) based on the ‘wow zone,’ as used in design thinking[4]. This is the zone for interventions most closely aligned with your selection criteria (address root causes), is feasible to implement, and is innovative in its scope.

You can facilitate this step by evaluating each intervention idea based on its feasibility and how likely it is to have a significant impact. It is helpful to arrange these factors on a matrix, which is shown here. You could do this by placing each idea on a sticky note, an individual piece of paper, or writing it directly on a matrix.

Adding Definition & Description

The ideal interventions are those in the Wow zone and the ‘early engagement zone.’ Once you have established these ideal interventions, they need to be defined and described in a way that others can understand, imagine, support, and implement. The intervention needs to be explained to fit the context in which it will be used. Initially, defining the intervention means establishing its scope and connecting it to the need or situation. To do so, you need to answer these questions:

- How will the intervention impact the needs or situation?

- Who is it intended to serve?

- For the intervention to have its intended impact, what does it need to look like?

- What should it include (space for gathering, training/education, a building with services, collaboration, etc.)

- Where should it be geographically/virtually located to meet the intended impact?

- How would the intervention build on assets that already exist?

- What is the likely impact of the intervention?

- How would it be sustainable?

Understanding these answers will help guide the next community planning steps, which are to essentially create the infrastructure in order to implement the intervention. The planning steps involve establishing the organizational structure, mission, work plan, and budget.

- Stroh, D.P. (2015). Systems thinking for social change: A practical guide to solving complex problems, avoiding unintended consequences, and achieving lasting results. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing. ↵

- Campbell, L.A., & Anderko, L. (2020). Moving Upstream From the Individual to the Community: Addressing Social Determinants of Health. NASN School Nurse, 35, 152 - 157. ↵

- The University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, 2023. www.countyhealthrankings.org ↵

- Liedtka, J.; Salzman, R.; Azer, D. (2017). Design thinking for the greater good: Innovation in the social sector. New York: Columbia University Press. ↵