40 Understanding Organizations

This section introduces various theories and phenomena to help us understand how organizations and individuals may be predisposed to hinder or support change.

Understanding Organizations as Social Systems

It is helpful to consider that organizations are a social system and to apply social science wisdom to understand their norms, how they engage in resistance, and factors that help facilitate change. Since these phenomena are driven by individual and collective action or inaction, social science theories are particularly relevant.

Organizations have the power to facilitate immense benefits to the community as well as perpetuate immense harm. Some law enforcement, health care, and child welfare organizations are examples of this. They share common missions—to protect, help, and serve—but have been known to do quite the opposite and cause harm to the people, families, and communities they’re meant to help.

Allen Johnson (2006)[1] reminds us that organizations need to be understood as social systems in order to understand the dynamics of change. As a social system, organizations exhibit a culture that is known to possess the characteristics likely to support or resist change.

The culture of an organization defines the norms of appropriate behavior, motivates individuals, and offers solutions where there is ambiguity. These are the norms related to what people wear, how people interact during their work, the tone of the in-person communication (casual vs. strictly professional), comfort with humor, whether people socialize during the work day (like at lunch), and many other workplace behaviors.

Organizational Culture Supporting Change

Some organizational cultures value innovation and change, while others value stability and equilibrium. The culture may not be clearly visible when you enter but it is likely felt. The culture governs the way a company processes information, its internal relations, and its values. Often, the culture becomes tangible or visible when it is violated, evoking a response like, “We just don’t do that here.”

It is important to understand how and why an organization may be predisposed to support rather than resist change. In the open source textbook, Focusing on Organizational Change, Judge (2012)[2] describes eight dimensions of an organizational culture open to change. They include:

- Trustworthy leadership: A trustworthy leader is someone who is not only perceived to be competent in leading the organization but also as someone who has the best interests of the organization as their priority.

- Trusting followers: People are predisposed to trust others. When an organization is filled with a critical mass of individuals who are hopeful, optimistic, and trusting, it will be well-positioned to experiment with new ways of operating.

- Capable champions: Since organizations tend to keep doing things how they are accustomed, they must identify, develop, and retain a core group of capable change champions in order to lead the change initiative(s).

- Involved middle management: Middle managers are pivotal figures in shaping the organization’s response to potential change initiatives, so their involvement is crucial to the organization’s capacity for change.

- Systems thinking: The mindset and infrastructure that support organization-wide engagement (budgetary, communication, collaboration, etc.) rather than isolating departments or organizational segments.

- Communication systems: Effective networks of information sharing and knowledge transfer (e-mail systems, face-to-face meetings, telephone calls, methods of announcement sharing).

- Accountable culture: System for tracking deadlines, whether outcomes are achieved, and evaluating impact.

- Innovative culture: An organization that emphasizes and values change rather than stability and equilibrium motivates individuals and offers solutions where there is ambiguity.

Organizational Communication Supporting Change

Centola (2021) contributes insight into the ways in which an organization can be more able to adapt to change, focusing on how information shared between system or organizational parts facilitates or hinders communication as well as what happens when we rely on the ‘social influencers.’

Myth of Social Star

Centola describes the concept of highly connected people, often identified as influencers—those who may seem logically helpful in spreading information that would facilitate change—but that is often not the case. Highly connected people or the “social star,” as Centola points out, are often not helpful at spreading innovation because they may be reluctant to embrace the idea, end up forming roadblocks, and slow down the spread of information rather than speed it up.[3] Centola suggests that it is more important to look for the special ‘places’ in a network rather than ‘people’ to facilitate change. An example of a special place in a network could be the front desk and administrative staff where all staff walk by and often interact with daily.

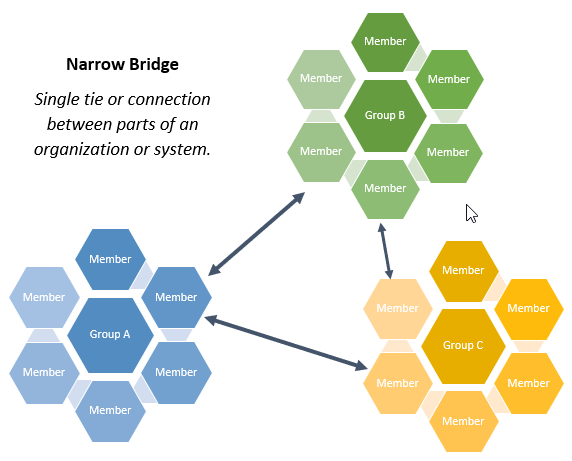

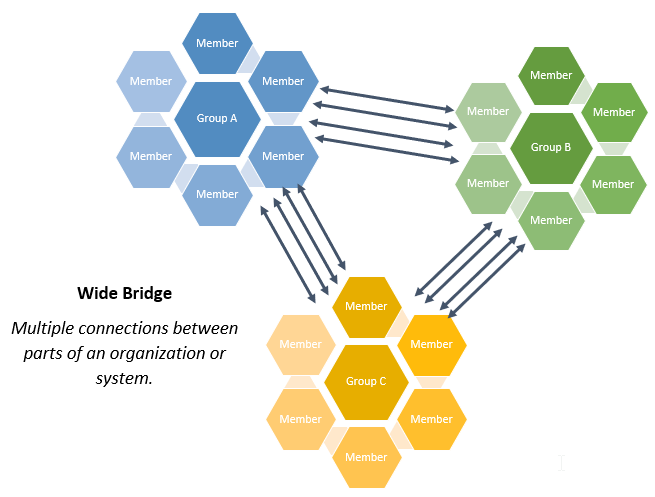

Narrow vs. Wide Communication Bridges

Centola also introduces the concept of ‘wide bridges‘ and ‘narrow bridges‘—communication channels between parts of an organization or system as the most effective for facilitating change. Narrow bridges are represented by an individual person who is relied upon to facilitate information between parts of an organization, as shown in the graphic below. This is a weak bridge because it relies upon one person to communicate information, focusing on their reach rather than the width of the connection.

In contrast, a wide bridge involves multiple connections of multiple people between organizations, which may represent a diversity of perspectives considered credible and relatable, resulting in a stronger connection.[4]

Social System and Social Identity Theories Impacting Change

There are three additional social system or social identity theories that influence the extent to which we are likely to engage in behaviors that facilitate or hinder change: Path of Least Resistance, Power of Bystanders, and Implicit Bias. These help explain the implications of resistance and the likelihood of facilitating the change that needs to take place.

Path of Least Resistance

Johnson (2006)[5] explains that the path of least resistance is the natural state of a social system. Since each system has its own set of norms and expectations, the easiest and most comfortable thing to do when entering a social system is to adopt the rules, expectations, and norms that exist—whether explicit or not. This is the ‘path of least resistance.’ Violating cultural norms and not following this path can be very consequential, leading to mild disapproval, punishment, or humiliation.

Johnson illuminates the path of least resistance through a story of an elevator, reminding us of the unwritten or spoken rules of elevator social norms. Within moments of entering an elevator, he conducted an experiment with the rules by choosing to stand and face the back wall instead of the established norm of facing the front. The tension and discomfort were palatable. He wasn’t saying anything or behaving in any way other than violating the norm of facing the front, but it caused discomfort for others and himself because he chose to engage in a path of greater rather than least resistance.

The risks of adopting harmful cultural norms, however, are also very consequential. Those who adopt harmful norms become a part of an organization or a system that perpetuates conditions such as oppression, inequity, harm, and mediocrity.

Power of Bystanders

Staub contributes another relevant theory for understanding organizational change and social change: the ‘bystander effect,’ which describes an individual’s likeliness to intervene in times of tragedy or change. This was famously described in 1970 by Litane and Darley in their research on the unresponsive bystander.[6] Staub explains that witnesses of violence or injustice have the opportunity to intervene, but they rarely do. Let that sink in for a moment. Why is this the case?

He states that the reasons are rooted in three primary things: background of the social conditions, past group relations, and devaluation of the victim’s group. The bystander is not responsible for the initial injustice or the violence, but due to lack of action, they have a responsibility for the continuation of the violence or injustice.

Bystander passivity not only communicates support to the perpetrators of the violence or injustice through inaction, but also influences other bystanders. By protecting themselves from other people’s suffering, the passive bystander reduces empathy and caring, making future action less likely. Passivity by bystanders suggests to other bystanders that inaction is acceptable, even appropriate.[7]

It is important to remember the bystander effect when looking at organizational change. Remember, Centola explained that a well-connected and influential person within an organization or a social system can be a roadblock for change; if that person is a passive bystander they are going to influence the likelihood that other people will fall into the pattern of standing by.[8]

Implicit Bias

Implicit bias refers to our “attitudes towards people or associating stereotypes with them without our conscious knowledge.”[9] This phenomenon is not unique to race, gender, country of origin, etc.

Implicit bias is critical for an organization to understand some of the internal forces driving ineffective outcomes and the need for change because it influences how we assess and respond to others. It also influences how we relate to individual and group strengths, needs, and challenges, therefore impacting our decision-making and directly influencing the assessment and intervention stages of our work. Cetola explains how implicit bias “permeates the professional norms and networks that reinforce them” (2021, pg. 281). [10] The implications of unchecked implicit bias cannot be understated; it leads to substandard care, inadequate treatment, perceptions of threat, and many other harmful impacts. It is no surprise that the outcomes of this disparate treatment are higher incarceration rates, health acuity, higher mortality, etc.

- Johnson, A. G. (2006). Privilege, power, and difference. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill. ↵

- Judge W. Q. (2012) Focusing on organizational change. Saylor Foundation. https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/128 ↵

- Centola, D. (2021). Change: How to make big things happen. New York: Little, Brown Spark. ↵

- Centola, D. (2021). Change: How to make big things happen. New York: Little, Brown Spark. ↵

- Johnson, A. G. (2006). Privilege, power, and difference. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw Hill. ↵

- Latane, B., & Darley, J. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help? New York, NY: Appleton-Crofts. ↵

- Staub, E. (2019). Witnesses/Bystanders: The tragic fruits of passivity, the power of bystanders, and promoting active bystandership in children, adults, and groups. Journal of Social Issues, 75(4), 1262–1293. https://doi-org.link.uwsuper.edu:9433/10.1111/josi.12351 ↵

- Centola, D. (2021). Change: How to make big things happen. New York: Little, Brown Spark. ↵

- Perception Institute. Implicit Bias. Para 1. https://perception.org/research/implicit-bias/ ↵

- Centola, D. (2021). Change: How to make big things happen. New York: Little, Brown Spark, pg. 281. ↵