4 Integrating Drones into USAF OPS (DeMaio)

“History is a vast early warning system.” At Dawn We Slept (Prange, 1981)

Special acknowledgement: The Wildcat team thanks Dr. Paul Schwennesen for his two-plus years in Ukraine, observing the Ukrainian Drone Forces on the front lines. His assistance on this chapter was invaluable to its preparation and first-hand accuracy.

Abbreviations

A2/AD – Anti Access / Area Denial

AAA – Anti-aircraft Artillery

ACE – Agile Combat Employment

AD – Air Defense

AFDN – Air Force Doctrine Note

AFDP – Air Force Doctrine Publication

AI – Artificial Intelligence

AMD – Active Air and Missile Defense

ATO – Air Tasking Order

BMD – Ballistic Missile Defense

C2 – Command and Control

CAS – Close Air Support

CSO – Chief of Space Operations

CSAF – Chief of Staff of the Air Force

CUAS – Counter Unmanned Aerial System

DAF – Department of the Air Force

DCA – Defensive Counterair

DoD – Department of Defense

DoDD – Department of Defense Directive

EMS – Electromagnetic Spectrum

FAARP – Forward Arming and Refueling Point

FOB – Forward Operating Base

FOS – Forward Operating Site

FPV – First Person Video

GBU – Guided Bomb Unit

HALE – High Altitude Long Endurance

IAF – Israeli Air Force

IDF – Israeli Defense Force

ISR – Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance

JP – Joint Publication

MOB – Main Operating Base

MTO – Mission-Type Orders

NASA – National Aeronautics and Space Administration

NATO – North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NWC – Naval War College

OCA – Offensive Counterair

OODA – Observe, Orient, Decide, Act

Ops – Operations

SAM – Surface to Air Missile

SEAD – Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses

TTP – Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures

USAF – United States Air Force

UAS – Unmanned Aerial Systems

UAV – Unmanned Aerial Vehicle

US – United States

USG – United States Government

USJFCOM – United States Joint Forces Command

USN – United States Navy

USSF – United States Space Force

USSOCOM – United States Special Operations Command

VR – Virtual Reality

WRM – War Reserve Material

Student Learning Objectives

- Identify lessons from history

- Discover drone combat in Ukraine

- Examine current operations with drones

- Understand Air Force Counterair doctrine

- Analyze a method for integrated Airpower

- Assess a strategy to integrate drones into Air Force operations

Vulnerability Repeated

On Sunday, December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese under the command of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, launched Operation Ai, a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor from the Kido Butai (mobile force) of six advanced aircraft carriers, the Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, Hiru, Shokaku, and Zuikaku. At 07:48 AM, 353 dive bombers, torpedo planes, and fighters executed a meticulously planned, two-hour-long attack. Zero Fighters gained and maintained Air Superiority throughout the entire strike. The first wave of aircraft was comprised of high-altitude dive bombers, striking airfields and other military facilities, and preventing United States (US) forces from executing any effective defense. The second wave was comprised of torpedo aircraft, crews specially trained to deliver modified torpedoes in shallow waters. The Japanese deployed 23 other warships, protecting the carriers with fighter caps and a ring of destroyers to thwart potential aircraft and submarine counterattacks. The attack killed 2,400, wounded 1200, and destroyed four battleships, three cruisers, and nearly 200 aircraft. Despite five battleships eventually being returned to service, the US suffered a significant tactical and operational defeat. However, the Japanese failed to engage any of the US Navy’s four aircraft carriers, which would turn the tide at Midway just 18 months later, awakening the American people, unleashing the juggernaut of US industry, and sealing Japan’s fate from the start. (Prange, 1981)

On Sunday, June 1, 2025, the Security Service of Ukraine launched a surprise attack against four Russian strategic air bases. The attack occurred on a holiday, the Military Transport Aviation Day, taking Russia by complete surprise.

The operation was planned over 18 months, and over 150 small Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS), or drones, were smuggled into Russia under the guise of normal day-to-day activities, bypassing the entire Russian security network, including their integrated air defense system. Planners staged first-person-video (FPV) drones in combination with Artificial Intelligence (AI) using ArduPilot as the backbone for command and control (C2) to execute the attack with commercially available equipment through the internet. The actual attack was conducted by 117 drones deep inside Russian territory, deployed from wooden containers onboard trucks, which were destroyed after launch. FPV pilots conducted real-time attacks on Oleyna, Dyagilevo, Ivanova Severny, and Belaya Air Bases, with video up-linked to operators inside Ukraine. The attack purportedly destroyed some 40 aircraft, including Tu-95 and Tu-22 bombers and several A-50 early warning aircraft remaining in the Russian inventory. Approximately 34% of Russia’s strategic cruise missile delivery aircraft and early warning aircraft were affected; aircraft that had been used to conduct attacks deep into Ukraine. Unlike the US after the Pearl Harbor attack, modern Russia does not have an extensive industrial base to draw from nor a population energized to defeat Ukraine. However, Russia is a resilient nation. (Bondar, 2025)

Operation Ai and Operation Spider Web adapted new technologies and methods to conduct audacious attacks, taking their enemies by complete surprise and scoring historic victories. Instinctively, military leaders knew or should have known the potential but failed to act in decisive ways, and many are now desperate to adapt their current force structures to this existential threat. Even faced with stark lessons from history and the recent showcasing of the destructive power of drones in combat, militaries continue to fall behind, namely the United States Air Force (USAF). The authors propose that the fundamental reason the USAF has lagged in this fight is a failure to admit that drones are Airpower. In truth, the demonstrated combat effectiveness and potential of drones is an existential threat to the USAF, its high-end force structure, and its relevance. The authors clearly recognize that drones alone cannot achieve all the missions of the USAF.

However, drones integrated with high-end Airpower will be ready for the battlespace and can perhaps solve the most enduring weakness of Airpower: a lack of persistence in the air. Finally, they propose that the faster the USAF integrates drones into Agile Combat Employment (ACE), the more survivable and lethal a deterrent it will be against our rising adversary, China. If the USAF fails, vulnerability will repeat itself soon.

Black Swan

“The inability to predict outliers implies the inability to predict the course of history.” The Black Swan (Taleb, 2010)

At the dawn of the 20th Century, the US rapidly emerged as a world power. To contend with potential adversaries in both oceans, the US developed color-coded plans, each color corresponding to a single adversary. War Plan Orange was initiated in 1897 to prepare the US for a potential conflict with Japan. Initially assigned to both the Army and Navy, it evolved primarily into a US Navy (USN) plan. The tenets of War Plan Orange endured over four decades of iteration, evolving with geopolitics, technology, and lessons learned from Wargaming. The Navy extensively developed and adapted the plan to changing conditions, resulting in three stages: secure the western United States; a decisive naval battle with Japan; and the surrender of Japan. Once the potential of a two-front war became a reality, the Navy planned for a resource-limited initial stage, Japan’s first-move attack, the retreat of US forces to its stronghold in Hawaii, national support, build-up of the industrial base, and an island-hopping campaign across the Pacific. (Miller, 1991) While they did not predict everything, practitioners accounted for new technology through continuous iterations of the plan. From 1919 to 1941, the Naval War College (NWC) conducted 318 wargames, dedicating ninety percent of the college’s curriculum to preparing, executing, and debriefing, most for War Plan Orange. (Pellegrino, 2024)

“The war with Japan had been enacted in the game rooms at the War College by so many people and in so many different ways that nothing that happened during the war was a surprise – absolutely nothing except the kamikaze tactics towards the end of the war. We (Adm. Nimitz) had not visualized these.” (Pellegrino, 2024)

Clearly, the US Navy recognized the real potential, if not the probability, of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. At the very least, the Navy should have known. Pearl Harbor was fortified with many defenses, including long-range Radar, reconnaissance aircraft, torpedo nets, and fleet protection around the islands. (Prange, 1981.) However, it appears the Navy relied too heavily on these defenses and did not think the Japanese would be so bold, despite 318 wargames at the NWC, the results of which were studied in depth by War Department officials. In much the same way, one can surmise the Russians were a victim of this thinking as well: a refusal to consider the outlier, or an attack deep in their homeland.. (Taleb, 2010) They clearly underestimated the tenacity of their Ukrainian opponent. The US cannot ignore the real possibility that Operation Spider Web will be repeated at an overseas base or on US soil. In reality, drones are rapidly evolving into one of the USAF’s deadliest threats. In the world’s most advanced drone battlespace, Ukraine, approximately 80% of kinetic battlefield losses (predominantly armor and infantry) are due to drone attacks. Currently, the US defense posture at the installation level and beyond is inadequate. Simple preparations may have mitigated or blunted Operation Spider Web, which the authors will explore later in this chapter.

Drone Combat in Ukraine

“A culture of innovation and adaptation has effectively inverted traditional asymmetry.” Dr. Paul Schwennesen

The following is a detailed description by Dr. Paul Schwennesen from his two-plus years in Ukraine, observing the Ukrainian Drone Forces on the front lines. His description details the evolution of the drones from simple reconnaissance platforms to a highly lethal threat, to the saturation of the airspace with a ubiquitous killer. He details his impressions in a haunting, first-person account, followed by background, technologies, offensive and defensive operations, and salient observations during his time in the battlespace.

A Revolution Observed

“On my sixth mission to the Ukrainian front, I first began to really grasp just how much the battlefield was shifting under the influence of drones. Our sniper/overwatch team had infiltrated to within a thousand meters of a Russian machine-gun position near Bakhmut. We moved cautiously, fully aware that both Ukrainian and Russian surveillance drones hovered overhead, attempting to track movement and direct artillery fire. At that time, drones were mostly a reconnaissance tool – annoying and dangerous, to be sure, but not yet decisive in their own right. Infantry tactics still held, and we could work our way forward without expecting an immediate strike from above. If we tried that same maneuver a year later, however, I sincerely doubt we would survive more than a few minutes – the pace of change has been that staggering. In just twelve months, the skies have become saturated not only with observers but with cheap, lethal, and near-constant direct-attack drones. What was at first a cat-and-mouse game between riflemen and spotters has become instead a near-continuous drone-driven exposure campaign. There’s nowhere to hide in contested zones where a lethal pan-opticon is on watch. I confess I was slow to recognize the shift. At first, I thought drones were just another step in the long march of weapons innovation – important, but manageable. But after seeing what they’ve become in places like Ukrainian-occupied Kursk, I’ve had to revise that view. This isn’t an incremental change; it’s a revolution in how lethal force is applied. The battlefield will never look the same again.

The war in Ukraine has proven many military assumptions wrong, but perhaps none more radically than those regarding the conduct of Airpower.

What began in 2022 as a textbook example of legacy air doctrine has since morphed into an extraordinary testbed for unmanned and low-cost aerial systems. Drone warfare – especially as employed by Ukrainian forces – is rapidly reshaping how strategists, operators, and policymakers must think about control of the skies. The conflict’s evolution from armor-led assaults to drone-saturated battlespaces reflects a broader truth: Airpower is no longer the exclusive domain of jet aircraft and deep-pocketed militaries. In its place is emerging a layered environment of cheap, disposable, and rapidly adaptable technologies that leverage first-person view (FPV) systems, fiber-optic “spool drones,” and autonomous decision-making tools. These developments represent not just a tactical innovation but a strategic shift in how wars are waged and won.”

A War of Necessity and Adaptation

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, conventional military logic presumed that Russia’s Air Superiority and overwhelming missile inventory would cripple Ukrainian defenses in a matter of days. A “ten-day Special Military Operation” would be quick, clean, and ignored by the rest of the world. Instead, Ukraine defended its homeland with surprising resolve, aided not only by Western arms shipments and foreign volunteers but through mobilizing a society-wide culture of innovation. Drones, used in improvised combat applications since at least 2014, became by late 2023 a sophisticated, multi-domain combat force. This force showed itself capable of executing complex surveillance, strike, and denial operations from the immediate frontline trenches to the farthest reaches of the Russian state itself. The “Special Military Operation” had become a quagmire, and the tables had effectively turned.

Ukraine’s defense is now rooted in a “losing slowly” strategy, deliberately trading Space for time and blood to wear down a numerically superior foe. In this framework, drones serve a dual purpose: they exact a constant, low-cost toll on Russian forces while denying them uncontested airspace and maneuver freedom. From trench-level FPV attacks to deep strikes on Black Sea naval assets, Ukraine’s drone force has become its de facto air force. Its drone campaigns underscore a deeper truth about modern war: adaptation, not legacy advantage, is the decisive currency. Where Russia relied on overwhelming firepower and massive mobilization of heavy assets, Ukraine relied on a decentralized ecosystem of coders, tinkerers, soldiers, and civilian innovators. Small teams experimented, failed, iterated, and scaled an evolutionary process that mirrored the resilience of the society at large. The result was a force that could respond in days or hours to battlefield challenges that would take Russia, or even NATO militaries, weeks, months, or even years to address through formal procurement cycles.

A culture of innovation and adaptation has effectively inverted traditional asymmetry. Rather than Russia holding the advantage by virtue of scale and resources, it is Ukraine’s lean and improvisational model that has imposed disproportionate costs. Every successful drone strike against a tank, a warship, or an oil depot reflects a broader truth: industrial-age militaries built around massed formations and capital-intensive platforms are increasingly vulnerable to the nimble, distributed tools of the information age. At the strategic level, this shift has global implications. Ukraine is not just fighting for survival; it is rewriting the grammar of warfare in real time. Its “drone air force” represents not only a stopgap against Russian dominance but a template for how smaller states, and nonstate actors, can resist larger powers. For the US and its allies, the lesson is stark. Those with the deepest arsenals may not win future conflicts. Still, those most willing to empower experimentation and embrace decentralization will allow adaptation to flourish within the harsh conditions of war.

Cheap, Smart, and Disposable

The types of drones now dominating the Ukrainian battlespace are diverse, and human operators guide most. First, FPV drones are operated in real time by ground-based teams (typically 4-4 members) using virtual reality (VR) goggles. These drones are cheap, fast, and deadly. They are often manually guided via analog signals directly into enemy positions or vehicles, functioning as precision-guided kamikazes. Many of these FPV drones are equipped with bespoke munitions packages built by frontline units scavenging explosives from other munitions and fitted into three-dimensional (3D) printed casings and homemade detonators. Second, fiber-optic drones are connected to operators via fiber cable (on the order of .22mm) rather than a radio signal connection, making them immune to jamming. This is a huge advantage in an Electronic Warfare-heavy environment like eastern Ukraine. Russians pioneered this technology and hold a slight edge in this domain, though Ukrainian operators are rapidly catching up.

Up and coming are autonomous systems using pre-programmed coordinates and artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled visual recognition (“pixel-lock”) technology. Some drones are now operating independently from human guidance, responding to terrain, movement, and target specifications with increasing sophistication. However, the current computing power and bandwidth needed to operate these drones are largely preclusive. While not fully operational yet, both Ukraine and Russia are exploring the use of multiple drones acting in coordinated fashion to overwhelm defenses; a harbinger of next-generation warfare where large swarms of AI-driven drones independently engage targets, largely undetected.

The adoption of these technologies reflects a broader phenomenon. In Ukraine, battlefield innovation is no longer coming from defense contractors with 10-year timelines.

It comes instead from the frontline workshops with hourly production cycles coordinated through a largely decentralized communication structure, based heavily on individual smartphone apps such as Signal and Discord. Innovation and evolution are on hyperdrive as operator feedback merges relatively seamlessly into back-shop engineering laboratories. The systematic, almost businesslike, pursuit of ever-improving performance may do more than anything to explain how Ukraine has transitioned from reliance on foreign aid to working rapidly toward self-sufficiency. The process has not been perfect, but Ukraine’s system of “democratized warfare” helps explain how it has successfully resisted Russia’s full-scale invasion for so long.

Drone Production

“The most effective weapons to arise from this new way of war are custom-built first-person-view (FPV) platforms made almost entirely in-country and often near the frontlines. These construction sites are often housed in roughly retrofitted civilian buildings where ultramodern 3D printer labs and advanced engineering assembly lines build the components needed in near real time. They drive a hyper-evolutionary engineering cycle that customizes weapons to fit the immediate needs of the day. It is not only the FPV hardware (typically 7-, 10- and increasingly 14-15-inch frames) that are made locally – advanced chipmakers are also involved. They are building and deploying cutting-edge Ukrainian flight controllers and processors with the understanding that Chinese supply lines are tenuous and could be rescinded at any time. While they still utilize cheap Chinese modules when convenient, they are aware they may need to build everything in-country at any moment. They are developing the production infrastructure to do so.

Heavy-lift drones are playing an increasing role in battlefield operations. The nondescript factory, which specialized in large agricultural drone sprayers before the war, now makes aerial sprayers that release defoliants and accelerants over Russian positions before immolating them with thermite. These factories incorporate real-time feedback from their frontline partners to build drones that iterate on heavy-lift designs based mainly on 4-, 6-, or 8-arm frames that can lift as much as 500 kilograms. The drones fold to fit into small pickups or SUVs for forward deployment and can be quickly adapted to fit various mission sets – from dropping cases of water bottles to friendly troops to mounting auto-aim machine guns. These heavy-lifters are becoming the new workhorses of the frontline.” (Schwennesen, 2025)

Offensive and Defensive Drone Operations

Offensively, Ukraine employs drones in a layered approach. In frontline attacks, FPV drones are used extensively against personnel, tanks, artillery positions, and bunkers. Depending on the sector, FPV strikes can account for as much as 80-90% of kinetic combat operations. In rear-area sabotage, long-range drones strike airfields, fuel depots, and even targets in Moscow, Olenya, and Yakutsk, demonstrating not only the reach but the symbolic striking power of unmanned systems. Reconnaissance and targeting teams employ small, hand-launched drones, providing real-time intelligence to artillery and counterbattery fire.

Defensively, Ukraine has pioneered an amazing array of capabilities. First, Ukraine drone forces utilize interdiction systems, comprised of Radar, laser, and acoustic sensors to track incoming unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), coupled with small-arms teams, and integrated air defense. In addition, Ukraine uses EW to jam and spoof Russian drones with increasing frequency, particularly around critical infrastructure. A curious twist on this has been Ukraine operators’ ability to intercept the video transmissions of enemy FPV platforms, effectively “seeing” what their adversary is attacking and evading accordingly. Finally, Ukraine uses adaptive infrastructure, consisting of bunkers, camouflage, mobile headquarters, and rapid insertion tactics have adapted to a reality where nothing is hidden from surveillance.

Democratization of Airpower

The ramifications of drone combat on modern Airpower are enormous. Drones have effectively “democratized the air,” with control of the air no longer requiring fifth-generation fighters or billion-dollar budgets. Inexpensive drones can achieve area denial, precision strike, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) roles at a fraction of the cost of traditional systems. In truth, a $500 drone can now blur the lines between strategy and tactics, influencing morale on a strategic level, as demonstrated in the Operation Spider Web attacks on symbolic targets deep inside Russia. Drones have also compressed the observe, orient, decide, and act (OODA) loops of traditional systems, allowing near-instant OODA cycles at the platoon level, and making traditional planning hierarchies obsolete. Finally, expensive manned aircraft, if unprotected, may increasingly yield to cheaper, attainable systems that can be deployed in volume and adapted in real time.

Airpower is really no longer about platforms; it is about effects. Indeed, it always has been. As B.J. Liddle Hart was fond of noting: “Air Power is, above all, a psychological weapon – and only short-sighted soldiers, too battle-minded, underrate the importance of psychological factors in war.” An overreliance on sophisticated airframes obscured the underlying strategic truth. Ukraine has shown us that persistent surveillance, ubiquitous precision, and democratized rapid iteration can be more decisive than massive defense infrastructures. Ukraine’s drone operations are not just a footnote to this war; they are its defining feature. For the future of Airpower, the lesson is clear: adaptability, cost-efficiency, and autonomy will shape the skies of 21st-century conflict far more than legacy assumptions about exquisite technologies and deep-pocketed training regimes.

The Lure of High-End Technology

For millennia, nations have sought to beat their enemies with the latest technology. From steel to gunpowder, the machine gun, the airplane, and so on, nations have staked great treasure on technology to prevail. Often, however, overconfidence in the promise of technology coupled with a disregard for the lessons of history has resulted in tragic defeat. The annals of Airpower are replete with examples. For example, the United States invested 35% of its total war production in Airpower, suffered 35% of all combat deaths in the air, yet only 20% of bombs hit their targets in precision bombing raids. However, Airpower was decisive with Air Superiority and in combination with Joint Force Operations. (Air University Press, 1987) Likewise, in Vietnam, the Department of Defense (DoD) put its faith in medium-range semi-active and heat-seeking missiles, losing mastery of basic air-to-air fighting skills and even foregoing an internal cannon in the F-4 Phantom. Air-to-air kill ratios plummeted from 10:1 in the Korean War to a dismal 2:1 in the early years of the Vietnam Conflict. Not until the USAF and NAVY established Fighter Weapons Schools did kill ratios climb significantly with a re-mastering of basic air-to-air combat skills and weapons of all types, including missiles and cannons. (Sayers, 2018)

From strategy to operations to tactics, US Airpower has historically focused on offense. While the current Air Force doctrine Publication 1-1 has evolved more towards joint force employment, past Airpower doctrine was “inherently offensive” in nature, as stated in “The Ten Propositions of Airpower” (Meilinger, 1994) This publication demonstrates the culture of technological superiority in the USAF’s application of Airpower; the desire to achieve rapid, decisive victory through exclusive technological superiority. In the author’s opinion, drones are antithetical to the USAF’s vision of Airpower. Other than high altitude or battlefield unmanned aerial systems, drones are perceived as inexpensive, low-end, and low-tech systems that cannot achieve the strategic, operational, and/or tactical victories originally envisioned by the USAF. Further, he has clear evidence that the USAF has ignored the existential threat drones pose, as demonstrated in Operation Spider Web.

From May 2021 to August 2022, the author commanded a fighter wing with a very similar problem set that the Russians faced. His Wing, a Guard base sitting on the corner of a local airport, had twenty fighters compressed into a small area of the base, much like Battleship Row at Pearl Harbor. Acknowledging the great vulnerability to the base, he initiated a counter-drone program, detailing theWing’s Security Forces Squadron to build a comprehensive program to detect, target, and mitigate drone threats and integrate with local law enforcement outside the gate. So convinced he was of the potential threat, he invited an intelligence aggressor squadron to monitor the Wingg for six months prior to a major ACE exercise, the first of its kind, exposing major lapses in security, including great vulnerability to drone attack. However, five years later, this program no longer exists at the Wing, and clearly, the threat is significantly greater as demonstrated by current events. Now, twenty new F-35s sit in a tightly packed space only 100 yards from the State Highway. These same vulnerabilities exist at dozens of facilities in all Federal, State, and local agencies nationwide.

Israel’s Attack on Iran

Some drone proponents have predicted the end of modern Airpower with ubiquitous swarms of AI assassin drones. In the author’s opinion, neither willful ignorance of drones nor relying solely upon them will lead to victory. As history has shown time and time again, steady, long-term integration of cutting-edge technology with a specific method of employment, and disciplined training and improvisation are the keys.

(Murray, 1996) Two current operations illustrate this point. On June 13, 2025, Israel commenced Operation Rising Lion, targeting Iranian ballistic missiles, air defenses, and nuclear facilities. While the IAF (Israeli Air Force) is considered one of the best in the world and could have executed these operations alone, Israel prepared the battlespace with FPV drones and anti-tank attacks deep inside Iran. In much the same fashion as Operation Spider Web, while Iran was focused on intercepting IAF fighters, Israeli FPV drones smuggled deep into Iran were released from trucks, assassinating key Iranian leaders, nuclear scientists, and military personnel. These attacks were followed closely by 200 IAF fighter aircraft, establishing Air Superiority and delivering precision weapons against critical targets. (Gunn, July 2, 2025)

The key to Operation Rising Lion was the integration of high-cost, low-density assets (F-35s) with high-density, low-cost assets (drones). The strike package included Harop loitering munitions to suppress Radar ahead of manned jets, an acknowledgment that even stealth aircraft benefit from disposable “pathfinders.” Iran’s Russian-supplied S-300 batteries and indigenous Bavar-373 systems struggled with saturation against massed inbound threats, especially when drones drew fire away from high-value aircraft. Israel’s use of unmanned assets helped limit pilot risk in what was effectively a high-threat penetration of contested airspace. Finally, Air superiority no longer means simply controlling the skies; it also means controlling the decision-making tempo by overwhelming defenses with layered threats, often with unmanned assets that can be delivered deep behind enemy lines.

US Strike on Iran

Iran retaliated against Israel’s strikes with ballistic missile and drone attacks, prompting the US to execute Operation Midnight Hammer with cruise missiles, followed by 125 aircraft, including B-2 Bombers delivering fourteen, 30,000-pound GBU-57 (guided bomb unit) Massive Ordnance Penetrators. The strikes allegedly destroyed the Fordow Uranium Enrichment Plant, Natanz Nuclear Facility, and the Isfahan Nuclear Technology Center. (Roque, 2025) While only the US has the technology and capability to conduct such an operation, clearly, Israel’s integration of drones and advanced aircraft demonstrated a state-of-the-art integrated operation. Unlike Israel’s strike, the US relied solely on conventional Airpower, perhaps giving up significant capabilities that drones could have provided in preparing the battlespace. Finally, US aircraft operate from perceived impunity, and ironically, “…the United States lacks the defenses against this kind of attack, both at home and abroad, and that gap in protection is becoming harder to ignore.” (Gunn, Ibid)

The key to Operation Midnight Hammer was that precision strike remains a unique, core US comparative advantage in the missile-drone age. By employing stealth bombers launched from the continental United States (behind a feint deployment at Diego Garcia), and supported by seamless refueling and drone-based reconnaissance capabilities, Washington underscored an unmatched ability to project force globally on short notice. The choice of weapons, stand-off cruise missiles supplemented by direct-penetration precision-guided munitions, reflected a careful balance: enough kinetic effect to neutralize hardened missile silos, command nodes, and Quds Force logistics hubs, while avoiding excessive collateral damage that could risk a spiral into all-out war. Operationally, the strike highlighted the US military’s capacity for “parallel warfare,” hitting multiple dispersed targets nearly simultaneously to overwhelm defenses. Iran’s layered but antiquated air defense system struggled to respond effectively, exposing vulnerabilities despite recent acquisitions from Russia and organic upgrades. Equally significant was the cyber-electronic warfare component. US planners reportedly suppressed portions of Iranian radar networks in real time, ensuring penetration corridors for bombers and missiles remained viable. Strategically, the operation functioned as both punishment and signaling. By striking Iran’s nuclear infrastructure, Washington aimed not only to degrade Iran’s forward-operational capability but also to deter further missile and proxy attacks against US and allied forces in the region. Yet, the restraint in target selection conveyed an implicit message: the United States retains escalation dominance but prefers calibrated deterrence to regime change.

The Drone Domain

The Department of the Air Force (DAF) is comprised of the United States Air Force (USAF) and the United States Space Force (USSF). While the DAF has one Secretary, the USAF is led by the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, and the USSF is led by the Chief of Space Operations (CSO). Department of Defense (DoD) Directive 5100.01 assigns the USAF and USSF each a “domain,” or region of physical distinction, which they are responsible for. (DoDD 5100.01, 2020) The DoD assigns the Air Domain to the USAF, which conducts eight functions to ensure control of the air. The DoD assigns the Space Domain to the USSF, which conducts five functions to ensure control in Space. (DoDD 5100.01, 2020) Despite the USAF and USSF being under one department, the distinctions between air and Space are critical in determining where responsibilities begin, overlap, and end.

Joint Publication 4-30 defines the air domain as “the atmosphere, beginning at the Earth’s surface, extending to the altitude where its effects upon operations become negligible.” (JP 4-30, 2019) Most Air Force aircraft fly below 60,000 feet, other than aircraft such as the U-2 and/or the RQ-4 Global Hawk high-altitude, long-endurance (HALE) unmanned aircraft. The DAF and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) generally specify fifty miles above the Earth’s surface, or approximately 264,000 feet, as the point where air blends significantly into Space. (Dobrijevic, 2022)

While this may not seem pertinent to low-altitude drone operations, their use is expanding rapidly into all domains, and it is crucial to determine which department will operate where. While clearly in the air domain, this issue was highlighted from January 28 to February 4, 2023, when China flew high-altitude balloons over the United States at approximately 55,000 feet. Shot down by F-22s, these balloons exploited a “seam” in terms of international law since there exists no international agreement defining sovereign airspace above a State. (Sent Into Space, 2023) In the Space domain, satellites operate freely, overflying other nations at will. Adversaries can employ and/or loiter armed platforms from extremely high altitudes, even into and from Space and other domains. For this chapter, however, the author will focus on low-altitude drones, with the distinct knowledge that they will enter and exit from and to multiple domains to an increasing degree. That said, the USAF must be prepared to conduct DCA operations in all domains, and increasingly, in concert with other agencies as drone operations rapidly expand across all domains.

Drone Doctrine

Control of the Air is the master construct under which the USAF operates. With the speed and reach of Airpower, it is easy to see how the USAF must control very large areas of the air to ensure it achieves its missions as well as those of all services and components. DoDD Directive 5100.01 details the eight functions of the USAF as follows:

(1) Conduct nuclear operations in support of strategic deterrence, to include providing and maintaining nuclear surety and capabilities.

(2) Conduct offensive and defensive operations, to include appropriate air and missile defense, to gain and maintain air superiority, and air supremacy as required, to enable the conduct of operations by US and allied land, sea, air, Space, and special operations forces.

(3) Conduct global precision attack, to include strategic attack, interdiction, close air support, and prompt global strike.

(4) Provide timely, global integrated intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capability and capacity from forward-deployed locations and globally distributed centers to support worldwide operations.

(5) Provide rapid global mobility to employ and sustain organic air and space forces and other Military Service and USSOCOM forces, as directed, to include airlift forces for airborne operations, air logistical support, tanker forces for in-flight refueling, and assets for aeromedical evacuation.

(6) Provide agile combat support to enhance the air and space campaign and the deployment, employment, sustainment, and redeployment of air and space forces and other forces operating within the air and space domains, to include joint air and space bases, and for the Armed Forces other than that which is organic to the individual Military Services and USSOCOM in coordination with the other Military Services, Combatant Commands, and USG departments and agencies.

(7) Conduct global personnel recovery operations, including theater-wide combat and civil search and rescue, in coordination with the other Military Services, USJFCOM, USSOCOM, and DoD Components.

(8) Conduct global integrated command and control for air and space operations.

The author contends that function number two is the most critical, by far. As the history of Airpower tells us, Air Superiority is essential for victory not only in the air but in all domains. Airpower is so critical that each service has “its own air force,” and in fact, the US Army has more airframes than the USAF. However, gaining and maintaining control of the air is not possible everywhere. AFDP 4-01 describes control of the air as follows:

Control of the air describes a level of influence in the air domain relative to that of an adversary. The relative degree of control is typically categorized within a spectrum ranging from parity, where neither adversary can claim control over the other, to air superiority, to air supremacy. To enable the successful execution of joint operations such as strategic attack, interdiction, and close air support (CAS), the desired degree of control is typically air superiority. In a peer or near-peer conflict, air superiority may not be achievable in all places or at all times.

AFDP 4-01 further describes control of the air as a continuum in which either friendly or adversary forces can achieve a relative level of control, either localized or broad and enduring, using the following definitions:

Air parity: a condition in which no force has control of the air. It is a situation in which both friendly and adversary land, maritime, and air operations may encounter significant interference by the opposing force.

Air Superiority: Air superiority is that degree of control of the air by one force that permits the conduct of its operations at a given time and place without prohibitive interference from air and missile threats.

Air Supremacy: that degree of control of the air wherein the opposing force is incapable of effective interference within the operational area using air and missile threats.

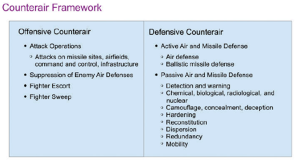

Coming full circle back to the functions of the USAF as per DoDD 1500.01, the USAF “missionizes” control of the air doctrine through the Counterair Framework. Counterair is divided into Offensive Counterair (OCA) and Defensive Counterair (DCA). The purpose of OCA is to dominate enemy airspace in order to gain freedom from attack and increased freedom of action.

It consists of Attack operations in order to degrade the adversary’s use of air and missile forces. Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD) neutralizes, degrades, and/or destroys enemy air defenses to allow friendly air operations. Fighter Escort accompanies friendly aircraft with air-to-air capabilities, and they may dual-role as SEAD platforms. Finally, Fighter Sweep is a mission designed to destroy enemy aircraft and/or targets of opportunity. In essence, OCA attacks the adversary’s offenses and defenses, and drones are very capable OCA platforms.

The purpose of DCA is to deny the adversary freedom to attack friendly forces in the air. DCA can be conducted in concert with OCA and consists of Active Air and Missile Defense (AMD) through an Integrated Air Defense System. DCA is also comprised of Air Defense (AD), utilizing Surface to Air Missiles (SAM), anti-aircraft artillery (AAA), and other electronic sensors and means, as well as Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD). Finally, DCA utilizes Passive Air and Missile Defense, such as camouflage, concealment, and deception. In essence, DCA utilizes passive and active defensive measures. Of particular interest, US forces have not conducted DCA to a great extent against a peer adversary since the Soviet Union; however, China increasingly poses a serious threat to US control of the air. (AFDP 4-01) Again, drones are very capable DCA platforms.

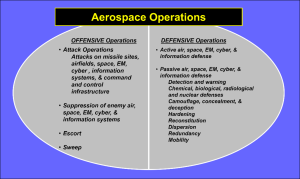

New technology and methods create a flurry of predictions regarding the nature and character of warfare, and drones are no different. As with all previous and current technologies, drones operate in domains and do not create a new domain in and of themselves. Other than nuclear weapons, no military service needs to have a doctrine dedicated exclusively to technology, and the current doctrine is a starting point to integrate new technology into current and future operations. USAF Doctrine, particularly Counterair, contains nearly all the doctrine needed to integrate drones successfully. In fact, the author contends that drones must be integrated into all USAF doctrine as a technology enhancer of USAF operations.

The author also proposes that drones are perhaps the first technology that truly spans all domains. As he previously discussed, drones can exploit the seams between Air, Space, Ground, Sea, Cyber, and the Electromagnetic Spectrum (EMS). In that light, the author proposes Aerospace Operations, combining the USAF domains as a simple yet comprehensive way to think about drone employment, crossing the seams of all domains. In this way, Airmen will not only innovate in the air domain but also integrate Airpower with all others.

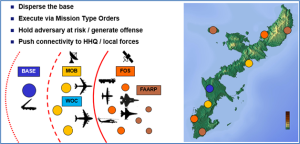

Agile Combat Employment

Rapid advances in adversary capabilities have eroded traditional US military advantages and freedom of maneuver, placing air bases considered at one point as sanctuaries at greatly increased risk. Historically, the United States has relied on overseas bases to project power. At the height of World War II, the United States had 93 air bases located around the world, 50 during the Cold War, and only 33 US air bases remain globally. Manpower had also dropped precipitously from 510,000 during the Cold War to approximately 320,000 today. In addition, potential adversaries have developed powerful Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) systems, putting these bases at great risk. To help contend with these developments, the USAF has developed Agile Combat Employment (ACE), or “a proactive and reactive operational scheme of maneuver executed within threat timelines to increase survivability while generating combat power.” (AFDN 1-21) The author assisted the USAF in developing ACE as part of Joint All-Domain Operations, to present our adversaries with operational dilemmas spanning across all domains. Designed primarily to contest peer adversaries at the operational level, ACE demands small, mobile units to operate from dispersed locations, complicating adversary targeting via rapid theater maneuver. ACE does this by shifting operations from centralized locations to smaller, dispersed locations and constant movement. (AFDN 1-21)

The ACE construct relies on three core enablers: Expeditionary and Multi-Capable Airmen, Mission Command, and Tailorable Force Packages. Multi-Capable Airmen not only know their own skills but also additional skills, enabling ACE and reducing the number of people needed at remote bases. Mission Command is the USAF’s Command and Control (C2) construct, which recognizes the need to push decision-making down to the lowest level possible. Using Centralized Command, leaders at the top communicate their intent through the Air Tasking Order (ATO) and push the operational level. Through Distributed Control, next echelon commanders issue Mission-Type Orders (MTO) to tactical units to ensure higher-level command intent is understood. Finally, Airmen at the tactical level receive orders and execute as the situation dictates, and/or requires innovation and adaptation to achieve the mission. In the end, Airmen are empowered to observe, orient, decide, and act within the commander’s intent and to keep the fight going if/when cut off from the next highest level and continuously communicate their status in order to provide feedback up the chain of command. ACE uses tailorable force packages to meet demand with an optimum force package to move quickly and execute independently if needed.

Finally, the ACE framework consists of five key elements: posture, C2, movement and maneuver, protection, and sustainment. Posturing in ACE is perhaps the most important in that “Forces must be able to rapidly execute operations from various locations with integrated capabilities and interoperability across the core functions.” An increased number of dispersed locations creates maneuver space and a deterrent that the adversary must spend time and treasure to track, identify, and engage. Commanders must be able to C2 and track forces with redundant capabilities across the domains, as ACE is an all-domain operation. It is quite probable that USAF forces conducting ACE will link up with Joint and/or Coalition forces to execute offense and defense based on the commander’s intent. Movement and maneuver throughout a number of locations again creates a targeting problem and causes the adversary to expend excess resources in an attempt to engage friendly forces, who, through their maneuver, in turn put adversary forces at risk. ACE enhances protection through a combination of offense, defense, and maneuver, forcing the adversary to find, fix, and track friendly forces. ACE relies heavily on war reserve material (WRM) and resupply to remote locations, known as agile logistics. Every aspect of ACE described heretofore by the author can and will be greatly enhanced with drones. From posture, C2, movement and maneuver, protection, and sustainment, drones are and will greatly enable USAF ACE operations to include conducting nearly every mission set in and responsibility assigned to the USAF. As with ACE itself, integration is the key. (ADFN 1-21)

Integrated Airpower

“The evidence points, first of all, to the importance of developing visions of the future.” Innovation in the Interwar Period (Murray, 1996)

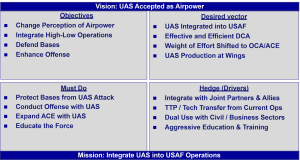

Based on the content of this chapter, the author contends that the USAF must model itself after the IAF by integrating drones into operations. The USAF and the IAF are very similar, operating high-end Airpower and conducting military operations across the spectrum of conflict. However, while Operations Rising Lion and Midnight Hammer were conducted in sequence, the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) integrated drone operations in much the same manner Ukraine did in Operation Spider Web; however, the USAF used only its high-end advantage. Clearly, the IDF has taken lessons from Ukraine, where its preparation with drones perhaps achieved results far greater than its high-end Airpower would likely have achieved on its own. Consequently, the author recommends a strategy for the USAF to integrate drones in the following priority order: DCA, OCA, and ACE. The author will demonstrate an example using, arguably, the most crucial US airbase in the Pacific, Kadena Air Base, Okinawa, Japan.

Kadena is strategically located, only 400 miles off the coast of China, and is the home of an amazing array of Airpower. The 18thWingg hosts an operations group of seven squadrons, including F-15, KC-135, EC-3, and HH-60 aircraft, as well as Aeromedical Evacuation, Pararescue, a Maintenance Group, Support Group, Medical Group, and Civil Engineer Group, and a host of other tenant units. This is the ideal location to model integrated drone operations because China has demonstrated its intention to use tens of thousands of drones, missiles, and projectiles to overwhelm US bases. Further, China has also fielded multi-domain drones, surfacing from the ocean, and taking flight against inland targets. (Honrada, 2025) However, Kadena’s aircraft are arrayed like Battleship Row with minimal defenses, and, therefore, its mission is at great risk at the very least from massive Chinese drone attacks.

Defensive Counterair (DCA)

Defense is by far the top priority in the current evolution of the drone war. Commonly known as Counter Unmanned Aerial Systems or Counter-UAS, the author will instead use established doctrinal terms (DCA, OCA, and ACE), thereby integrating drones with all other USAF platforms, capabilities, technologies, and missions. That said, US airbases must execute the principles of DCA with active and passive defenses. The Versus UAS/cUAS Symposium & Demonstration held at Camp Grafton, North Dakota, from August 20 to 22, 2025, provided multiple briefings from operators from Israel, Ukraine, and Estonia, regarding cutting-edge DCA methods in their respective battlespaces. Common to all is a multi-layered defense using the following (Balshai, 2025):

Active Defenses

- – Mobile Active Sensor Platforms

- Radar

- Therma

- Electrooptical

- Laser Range Finder

- – Mobile Interceptor Launchers

- Drone Nets

- Kinetic Multi-Rotor & Fixed-Wing Interceptor Drones with AI Targeting

- – Kinetic

- Mobile Kinetic Systems

- Handheld Weapons

Passive Defenses

- – Stationary Passive Sensors and Jammers

- Acoustic

- Radio Frequency with Cameras

- – Physical Protection

- Camouflage & Concealment

- Dispersion & Movement (ACE)

Perhaps most critical, Kadena must field an all-weather C2 system to provide a common operating picture, integrating defenses with software-defined configurations. The C2 system should also tie into conventional aircraft and missile defense as well. This layered defense must evolve rapidly to counter daily innovation/adaptation of drone systems, which means the USAF must follow its own doctrine, allowing Airmen at all levels to execute Mission Command Doctrine as published. The base must have multiple drone shops, building and modifying “standard configuration drones” for the ever-changing mission. Defending the base against scores of weapons will be extremely difficult, so every Airman must take part. In this way, Airmen have a part in defending the base. A well-defended base will enhance OCA and ACE, allowing the base to conduct offense and defense at the same time, as per Counterair Doctrine.

Offensive Counterair (OCA)

Again, the IAF’s execution of Operation Rising Lion serves as a model for the USAF. In much the same way that Israel prepared the battlespace with FPV drones, the USAF can use drones to assist the 18thWingg (in this case) with ISR, preparatory strikes, and/or creating mass for follow-on air operations by high-end platforms. The ultra-long distances of the Pacific Theater require drone strikes to be planned and executed by an Air Operations Center, in concert with Joint and Coalition Forces. However, the 18thWingg will likely utilize OCA in concert with ACE.

Agile Combat Employment (ACE)

ACE is a strategy utilizing small, mobile units operating from dispersed locations, maneuvering rapidly with decentralized execution, and complicating adversary targeting through multiple dilemmas. (AFDN 1-21) Drones are tailor-made for ACE operations because they provide mass and persistence in the air, which traditional high-demand, low-density assets do not have. Referencing Figure 10, Kadena is hypothetically dispersed upon certain indicators of enemy actions/intentions to Main Operating Bases (MOB), Forward Operating Sites (FOS), and Forward Arming and Refueling Point (FAARP). Logistics is critical to ACE, and drones can easily perform this function 24/7. In addition, they can perform DCA, OCA, and ISR, as well as serve as airborne C2 nodes during ACE Operations.

Operations in the Pacific will very likely require “island hopping” during ACE. Again, drones can transport fuel, weapons, and supplies to forward locations as well as perform DCA and OCA. In addition, aircraft can transport drones with them to perform required tasks. Fighter aircraft can utilize the MXU-648 Travel Pod, which measures just under eleven feet long and nineteen inches in diameter, to carry a small cache of drones. The pods are carried externally on all fighters, except the F-35. If one or more aircraft carry drones onboard, operators can download and employ the equipment in unprepared, remote locations to access the order of battle and conduct the mission required.

Way Ahead

“Our Air Force must accelerate change to control and exploit the air domain to the standard the Nation expects and requires from us. If we don’t change – if we fail to adapt – we risk losing the certainty with which we have defended our national interests for decades.” (Brown, 2020)

For the USAF, the reality of drone combat is sobering. Adversaries no longer need to destroy exquisite assets to erode American superiority; they need only disrupt, confuse, and degrade operations through massed swarms or persistent reconnaissance. As Ukraine has shown against a peer adversary, the cumulative effects of constant drone pressure can paralyze logistics, erode morale, and blunt technological advantage.

The sheer number of resources required to counter swarms, whether through kinetic interceptors, electronic warfare, or layered defenses, threatens to exhaust US forces long before the adversary’s will or capacity is broken. Both the IAF and US strikes on Iran underscore a growing vulnerability:

Conventional aircraft, particularly non-stealth legacy fighters and rotary-wing assets, are increasingly at risk from small, smart, and swarming drones. For the US, the challenge is to internalize these lessons quickly. Legacy acquisition pipelines are far too slow to keep pace with the speed of drone innovation. Suppose the USAF does not capture and adapt the TTPs emerging from Israel and Ukraine now. In that case, it risks encountering them later, refined, scaled, and turned against US forces by adversaries who chose the moment to learn faster.

The USAF has no time to spare in integrating drones into its operations. Faced with the devastating results of Operation Spider Web and the strikes in Iran, the USAF cannot ignore the existential threat it faces, and it must model itself after the IDF immediately. Referencing the author’s strategy in Figure 11, the vision of accepting drones as legitimate Airpower and the mission of integrating them into USAF operations are the ultimate goals; however, defending bases is by far the top priority. First, the USAF must construct layered defense systems at bases in the front lines in the Pacific and other combat zones with active and passive defenses. Concurrently, the USAF must begin to integrate drones into offensive operations and into ACE. The USAF will not be alone: it must work hand-in-hand with Joint partners and allies, as well as with the Civil and Business sectors, to secure the US both at home and abroad. Current programs to transfer tactics, techniques, and procedures, as well as technology, from combat zones are underway, but must be greatly expanded. The USAF must also embark on an aggressive program to train its Airmen how to construct and employ drones to defend the base and take the fight to the adversary.

From Ukraine’s trench-level FPVs to Israeli and American high-tech air packages, the trajectory is clear: the future of Airpower is less about dominance through sheer technological superiority and more about resilient, adaptive, and distributed force employment. For the first time in over a century of Airpower, nonstate actors can build their own air forces and challenge nation-states for control of the air. The skies are no longer ruled solely by the fastest or stealthiest jets; they are shaped by whoever can integrate sensors, shooters, and decision-making loops faster than their opponent. In that sense, the drone age doesn’t replace Airpower. It is Airpower.

References

Air University Press. (1981, October). The United States Strategic Bombing Surveys. Retrieved from: https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/AUPress/Books/B_0020_SPANGRUD_STRATEGIC_BOMBING_SURVEYS.PDF

Air Force Doctrine Note (AFDN) 1-21. (2024). Agile Combat Employment. Retrieved from US Air Force Doctrine: https://www.doctrine.af.mil/Operational-Level-Doctrine/AFDN-1-21-Agile- Combat-Employment/

Air Force News Service. (2020). CSAF Releases Orders to Accelerate Change Across Air Force. Retrieved from Air Force Homepage: https://www.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2442546/csaf-releases-action-orders-to-accelerate-change-across-air-force/

Air Force Publication (AFDP) 4-01. (2024, June 18). Counterair. Retrieved from US Air Force Doctrine: https://www.doctrine.af.mil/Operational-Level-Doctrine/AFDN-1-21-Agile- Combat-Employment/

Balshai, Kuprineko, Molloy, Tamm. (2025). Versus UAS/cUAS Symposium & Demonstration, Camp Grafton, North Dakota.

Bondar. (2025, June 2). How Ukraine’s Operation “Spider’s Web” Redefines Asymmetric Warfare. Retrieved from Center for Strategic & International Studies: https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-ukraines-spider-web-operation-redefines-asymmetric-warfare

Department of Defense Directive (DoDD) 5100.01. (2020) 5100.01: Functions of the Department of Defense and Its Major Components. Retrieved from: https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodd/510001p.pdf

Dobrijevic, May. (2022). The Karman Line: Where Does Space Begin? Retrieved from Space.com: https://www.space.com/karman-line-where-does-space-begin

Hammond. (2001). The Mind of War. New York: Smithsonian Institution.

Honrada (2025). China’s Air-Sea Drone Could Rewrite the Rules of Naval Warfare. Retrieved from Asia Times: https://asiatimes.com/2025/01/chinas-air-sea-drone-could-rewrite-the-rules-of-naval-warfare/#

Hudson, Nakashima, and Lamothe (2023). US Declassifies Balloon Intelligence, Calls Out China for Spying. Retrieved from the Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2023/02/09/chinese-balloon-surveillance-program/

Joint Publication (JP) 3.0. (2019). Joint Air Operations. Retrieved from https://irp.fas.org/doddir/dod/jp3_30.pdf

Liddell Hart. Retrieved from Minimalist Quotes: https://www.azquotes.com/quotes/topics/air-power.html

Meilinger (1994). Ten Propositions Regarding Airpower. Retrieved from https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/ASPJ/journals/Chronicles/meil.pdf

Miller. (1991). War Plan Orange: The US Strategy to Defeat Japan 1897-1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Murray and Millet. (1996). Military Innovation in the Interwar Period. Cambridge University Press.

Pellegrino. (2024). War Plan Orange: History and Mythology. Retrieved from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KXal8JUqAfQ

Prager. (1981). At Dawn We Slept. New York: Penguin Books.

Roque. (2025). Operation Midnight Hammer: Now the US Conducted Surprise Attacks on Iran. Retrieved from: https://breakingdefense.com/2025/06/operation-midnight-hammer-how-the-us-conducted-surprise-strikes-on-iran/

Sayers. (2018) The Vietnam Air War’s Great Kill-Ratio Debate. Retrieved from Historynet: https://www.historynet.com/great-kill-ratio-debate/

Schwennesen. (2024). Drones and Asymmetric Warfare in Ukraine and Israel. Retrieved from Global Information Services: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/drones-ukraine-israel/

Schwennesen. (2025). Eyewitness to War: Ukrainian Ingenuity and a New Kind of War. Retrieved at GIS Reports: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/

Schwennesen and Kryzhanivska. (2025). Frontline Innovation and Domestic Production: The Keys to Ukraine’s Journey Toward Defense Self-Reliance. Retrieved at Modern Warfare Institute: https://mwi.westpoint.edu/frontline-innovation-and-domestic-production-the-keys-to-ukraines-journey-toward-defense-self-reliance/

Taleb. (2010). The Black Swan. New York: Random House.

Gunn. (2025). How Iran’s Air Defense System Was Defeated so Quickly. Retrieved from: https://taskandpurpose.com/news/iran-israel-air-defense-rising-lion/

Sent Into Space. (2023). China’s “Spy Balloon” Explained by High Altitude Balloon Experts. Retrieved from Sent Into Space: https://www.sentintospace.com/post/china-high-altitude-spy-balloon-explained

Thomas. (2023). How Many Ships and Aircraft Were Used by Japan in the Attack on Pearl Harbor? Retrieved from Defense Reform: https://defensereform.org/how-many-ships-and-aircraft-were-used-by-japan-in-the-attack-on-pearl-harbor/