6 Port Security Law In The United States (Lonstein)

Introduction to US Port Security Laws

The United States’ seaports serve as the backbone of an economy that handles over $5 trillion in goods annually. Simultaneously, the port system plays a crucial role in national security. Ports interface with critical infrastructure sectors, including transportation, energy, and defense, making them high-value targets for potential threats.

Historical review of port security and regulation

Revolutionary Era

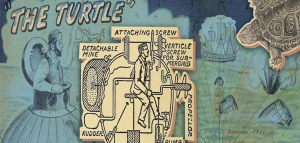

Tracing port security back to the Revolutionary War era, United States port security was, like the fledgling United States of America, a ragtag mosaic of navies, including the Continental Navy, the Army-led Navy, various state navies, as well as Privateers (also known as pirates or naval mercenaries). Citizens invented ad hoc defenses of inland waterways and ports, including various home-brew devices such as barrels of gunpowder and the “Turtle” invented by Davis Bushnell.

Prior to and during the Revolutionary War, the thirteen colonies of what is now the United States were subject to an increasing regime of regulation which were designed to rein in the colonies and frustrate their ability to trade and industrialize. Two of the many enactments of the Crown that created significant tension were the Navigation Acts, a protectionist series of laws enacted in 1650. These mercantilist laws were designed to protect the British Empire and dissuade the importation of goods from other nations. Key provisions restricted the export of certain goods—such as tobacco, sugar, and cotton—to England alone, while imposing duties and inspections on goods entering or leaving colonial ports. These laws effectively gave the British government control over American maritime commerce and customs enforcement. In 1775, the British further stoked the embers of the Revolutionary War by enacting the Prohibitory Acts, which removed the colonies from the protection of the Crown, banned trade with them, and allowed the seizure of American ships at sea. (British Parliament, 1775) As a result of the Act, the colonists resorted to smuggling to evade duties, and confrontations with British customs officials escalated tensions. The combination of the Navigation Acts and the Prohibition Act served as an early flashpoint in the broader struggle over sovereignty and legal authority that would culminate in the American Revolution. Why was Britain escalating the enforcement of its maritime and port regulations?

The Colonists, just one month before Parliament enacted the Prohibition Act, the Continental Congress enacted its Resolution on November 25, 1775. The first two paragraphs of the Resolution laid down the gauntlet to the British:

“1. That all such ships of War, frigates, sloops, cutters, and armed vessels as are or shall be employed in the present cruel and unjust War against the United Colonies, and shall fall into the hands of, or be taken by the inhabitants thereof, be seized and forfeited to, and for the purposes hereinafter mentioned.

- That all transport vessels in the same service, having on board any troops, arms, ammunition, cloathing, provisions, or military or naval stores, of what kind soever, and all vessels to whomsoever belonging, that shall be employed in carrying provisions or other necessaries to the British army or armies, or Navy, that now are or shall hereafter be within any of the United Colonies, shall be liable to seizure, but that the said cargoes only be liable to forfeiture and confiscation, unless the said vessels so employed belong to an inhabitant or inhabitants of these United Colonies; in which case the said vessel or vessels, together with her or their cargo, shall be liable to confiscation.” (United States Navy, 2017), citing (Clarke, William Bell, 1966)

In 1776, the Continental Congress formalized the process for commissioning and establishing rules of operation and conduct for privateers, authorizing them to seize British vessels and cargo. (Congress L. o.., 1776)

Transition: From Independence to Industrial Super-Power

Between the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, American port security and maritime law had become more comprehensive due to the exponential growth of international trade at sea. In the 1770s, the colonies’ maritime defenses consisted of a patchwork of local navies, privateers, and militias. Regulation was minimal, and those that did exist were often ad hoc, driven by wartime expedience rather than long-term strategy.

The early republic, however, quickly recognized the strategic value of secure ports and regulated maritime commerce. In the decades after independence, Congress authorized the creation of the Revenue Cutter Service (1790) (later the United States Coast Guard), which was tasked with enforcing customs laws, combating smuggling, and safeguarding America’s growing coastal trade.

Founded by none other than Alexander Hamilton, the concept of a Coast Guard was introduced in Federalist Papers No. 12 on November 27, 1787.

“A few armed vessels, judiciously stationed at the entrances of our ports, might at a small expense be made useful sentinels of the laws. Moreover, since the government has the same interest in preventing violations everywhere, the cooperation of its measures in each State would have a powerful tendency to render them effective. Here also we should preserve by Union, an advantage which nature holds out to us, and which would be relinquished by separation.” (Hamilton, 1987)

The United States Navy

Created during the Revolutionary War, the Continental Navy was born of necessity. British blockades of colonial ports disrupted trade and threatened the colonies’ ability to survive. The Continental Navy’s initial mission was both strategic and economic, involving the interception of British supply ships, disrupting British commerce, while simultaneously protecting the fledgling nation’s ability to engage in the commerce needed to support its war efforts.

The first naval ships were merchant vessels that were converted into makeshift warships. Although British Battleships and Frigates were larger and more powerful, what the American Navy lacked in firepower, it made up for with conviction or purpose. It served as a powerful symbol of defiance of the Crown. Commanders such as John Paul Jones demonstrated that, despite the colonial forces’ military handicaps, daring tactics could undermine Britain’s maritime dominance. Jones’s victory over HMS Serapis in 1779 became legendary, proving that American seamanship could stand against the Royal Navy. (Norton, 2019)

By the end of the Revolutionary War, the Continental Navy’s ships had been sunk, captured, or sold. In 1784, Congress officially disbanded the force due to the financial strain of maintaining warships in peacetime. The absence of a national navy left US merchant vessels vulnerable to piracy and foreign interference. The Revenue Cutter Service oversaw customs enforcement and anti-smuggling duties, but it lacked the capacity for high-seas operations. American ships in the Mediterranean soon fell prey to Barbary pirates, and both Britain and France harassed US commerce during the Napoleonic Wars. (Command, 2019)

Following the re-establishment of the United States Navy and the Revenue Cutter Service, the federal government began to codify laws to protect ports, regulate maritime commerce, and assert sovereignty over US waters. These early measures reflected a shift from purely military defense to a dual system, combining military deterrence and legal Control. The development of a hybrid port security framework of laws and assets would prove vital as the world continued industrialization. International shipping was an essential component of the United States’ expanding role as a major player in the nascent global economy, and perhaps most important, creating a regime of regulation needed to support the economic needs of the United States.

Toward that end, at the end of the 18th Century the United States began to enact laws and create infrastructure needed to support global commerce, This meant the capability of ports capable of handling larger vessels and laws creating rules, regulations and enforcement entities to ensure that ports could support a massive increase in cargo, traffic and the attendants threats which accompany large scale commerce. Most importantly, the collection of Tariffs at its ports would be essential to the survival of the fledgling nation.

According to the United States International Trade Commission “The 1789 tariff was not strictly a revenue act. Its first section declared that it was “necessary for the support of government, for the discharge of the debts of the United States, and the encouragement and protection of manufactures . . .. ” Many of the commodities assigned specific rates had been selected because they were produced within the United States. The specific rates were set higher than the standard 5 percent ad valorem rate to encourage people in the United States to buy from domestic producers. As protective measures, these early tariffs proved too low to be effective.” (Dobson, 1976)

The Tariff Act of 1789 (Collection Act of 1789)

The Tariff Act of 1789 and its subsequent amendments laid the foundation for all subsequent customs enforcement. Major components of the Act and subsequent amendments included the establishment of import duties as the primary source of federal revenue. It also created the Customs Service, staffed with customs collectors, naval officers, and surveyors in designated ports of entry. It authorized the use of the Revenue Cutter Service to board, inspect, and seize vessels suspected of smuggling or evading duties. (Congress U. S., 1789)

By the early 19th century, US port security law was expanded to Customs enforcement, smuggling interdiction, quarantine regulations enforcement and navigation control the designation of shipping channels, anchorage points, and pilotage requirement were other significant functions introduced under the Act.

The Embargo Act of 1807 and Port Closures

One of the most dramatic exercises of the federal port authority came with the Embargo Act of 1807, passed under President Thomas Jefferson. In response to British and French interference with US shipping during the Napoleonic Wars, the Act prohibited all American ships from sailing to foreign ports, effectively shut down international trade at US ports, authorized port inspectors and customs officers to detain vessels suspected of violating the Embargo.

While the Embargo devastated the American shipping industry and was deeply unpopular, it marked a precedent for using port regulations as a tool of foreign policy and national security. (United States Congress, 1807)

In March 1809, Congress passed the Non-Intercourse Act, an attempt to undo the crippling effects of the Embargo Act of 1807. Specifically, the 1809 Non-Intercourse Act was an attempt to narrow the scope and associated harms of the Embargo Act of 1807Some of the major functional and legal modifications included establishing Customs officials as the front-line enforcers of the Act, screening all ships leaving or entering US ports for prohibited trade with Britain or France. Masters of vessels were required to file detailed manifests and sworn declarations of their destinations, often backed by bonds that could be forfeited if illegal trade were discovered. Customs officers gained expanded boarding and inspection powers to verify cargo and destinations, which increased their role as security agents, not just tax collectors.

Revenue Cutter Service vessels patrolled harbor approaches, river mouths, and coastal waters to intercept ships attempting to evade the restrictions. Patrolling shifted from primarily customs revenue collection to maritime interdiction, blending economic enforcement with national security objectives. This blurred the line between “civil” customs enforcement and “military” naval operations in US port security.

Vessels could be detained in port if their declared cargo or route suggested trade with restricted nations. Clearance papers were strictly controlled; a ship could not legally depart without proof of compliance with the regulations. Inspectors worked closely with harbor pilots and dock authorities to monitor vessel traffic, creating an early form of port movement control system.

Ports with strong historical trade ties to British or French territories—especially in New England and the Gulf Coast—saw intensified anti-smuggling enforcement. Small craft, including coastal schooners and fishing boats, were closely monitored to prevent covert runs to neutral ports for transshipment to prohibited destinations. Smuggling cases often led to the seizure of vessels at the dock, making port enforcement a visible deterrent. (United States Congress, 1809)

Independence, Industrialization to Incompatibility; the War of 1812 through the Civil War

The War of 1812 laws granted the President power to close harbors to enemy ships, detain foreign vessels in US ports, and direct naval and customs resources jointly to secure harbors. This created the legal precedent for federalizing and militarizing port security during national emergencies. The Revenue Cutter Service operated under naval command when required—foreshadowing its later wartime integration. (Madison, 1812)

After the War of 1812, the critical role of the Ports of the United States continued to evolve both from a national defense perspective as well as the critical economic function they played in an industrializing world, with faster and larger ships to export American goods all over the world, as well as service as import hubs where tariffs were collected. After 1815, Congress did not dismantle wartime port security powers—instead, they codified portions into standing law:

Anti-piracy acts (1819–1825) – Allowed US naval forces and cutters to patrol harbors and seize vessels engaged in piracy or illegal slave trade. (United States Congress, 1819)

Neutrality Acts (1817, 1818) – Criminalized outfitting foreign warships in US ports, extending federal Control over dockside activities. (Annals of Congress, 1817) Post-war vulnerability led to the Third System of Seacoast Fortifications (1816 onward), placing heavy fortifications at major ports (e.g., Fort Monroe, Fort Sumter). These forts were designed with integrated sea approaches—meaning that any ship entering the port had to pass through the defensive artillery range under military observation. This blending of static defenses and mobile enforcement created a layered security model for ports.

The Civil War: The Union Blockade (1861–1865)

Lincoln’s Proclamation of Blockade (April 1861) was directly modeled on War of 1812 concepts but scaled up massively. The President invoked wartime powers to control all southern ports, deny access to Confederate shipping, and authorize seizure of blockade runners. This proclamation allowed the Navy to patrol offshore (blue-water perimeter); Revenue cutters, customs officers, and Army harbor forts enforced security inside the port approaches and allowed port closure authority. Just as in 1812, ports could be fully closed to all foreign trade for security reasons—except the Civil War blockade lasted four years and covered thousands of miles of coastline. (Lincoln, Abraham, President, 1861)

Post-Civil War Period

Ports became critical points for disease control in the late 19th century. The National Quarantine Act of 1878 gave the Marine Hospital Service (later the Public Health Service) authority to enforce quarantine at US ports to stop yellow fever and cholera outbreaks. (Forty-Fifth Congress, 1878)

Ships had to file health manifests declaring onboard illnesses, submit to inspection before docking, and remain in offshore quarantine if the disease was suspected. Immigration was increasingly regulated at major seaports, especially New York, Boston, and San Francisco, with the Page Act of 1875 restricting the immigration of “undesirable” laborers and women from Asia. Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 – Gave customs and immigration officers joint authority to inspect passengers and enforce bans at ports of entry. Immigration Act of 1891 (Fifty-first Congress, 1891)

Harbors as Strategic Assets

The Navy retained coaling stations and shipyards in major ports, ensuring readiness for rapid mobilization. Fortifications from the Civil War era remained active, often upgraded with Endicott Period coastal defenses in the 1890s, which integrated artillery coverage with controlled harbor access. Harbors began hosting permanent customs guard detachments, a precursor to today’s integrated port security forces.

The 20th Century – A Modern Era Requires Modern Ports

The Creation of the US Coast Guard (1915) (Congress S.-T., 1915). The Revenue Cutter Service merged with the Life-Saving Service to form the US Coast Guard, officially charged with port patrols and interdiction, enforcement of customs, navigation, and safety laws, and search and rescue and coastal defense roles.

This gave the federal government a unified maritime security force capable of enforcing port regulations and defending against foreign threats.

World War I (1914–1918). Harbor Defense and Shipping Control. The Shipping Act of 1916 established the US Shipping Board to regulate merchant shipping and control port facilities critical to war efforts. The Espionage Act of 1917 included provisions for harbor security, authorizing Control of vessel movements within ports, exclusion zones around military facilities, and search and seizure authority for suspected saboteurs or spies. The Alien Enemy Act (WWI amendments) restricted port access for foreign nationals from countries deemed hostile. (Sixty-Fifth Congress, 2017)

(Courtesy National Constitution Center) (McCay, 1917)

Prohibition Era (1920–1933). Anti-Smuggling Port Enforcement

The Volstead Act (1919), enforcing Prohibition, transformed port security into a massive anti-smuggling operation. The Coast Guard expanded dramatically, patrolling harbor entrances and inspecting incoming ships for contraband alcohol. Intelligence-sharing between customs inspectors and the Coast Guard. (Sixty Sixth Congress of the United States, 1919)

World War II (1939–1945): Full Militarization of Port Security

Executive Order 9074 (1942) placed all US port facilities under the US Coast Guard Captain of the Port system, giving the Coast Guard complete Control over vessel movement within harbors, waterfront facility access, and issuance of port entry permits. (Roosevelt, 1942)

The Magnuson Act of 1950 (passed just after World War II but rooted in wartime powers) formally codified these authorities, allowing the President to control vessel access to US waters for national security reasons. Volunteer Port Security Force (VPSF) was created to supplement their forces further. The USCG established the VPSF, comprised of trained civilians who serve part-time, often without pay, to manage port security duties ashore.

It Takes a Community – The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

Project Underworld, also known as Operation Underworld, was a covert World War II-era operation (1942–1945) in which the US government—in particular, the Navy’s Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI)—collaborated with organized crime figures, predominantly the Italian-American and Jewish Mafia, to enhance security at the Port of New York and other northeastern US harbors. Sabotage fears escalated following the mysterious fire and sinking of the SS Normandie in New York Harbor in February 1942. Although it was deemed accidental, many feared enemy agents had orchestrated its sinking.

While German U-boats were wreaking havoc on Atlantic supply lines, ONI suspected that Axis saboteurs might be operating on the home front. Conventional law enforcement was ineffective in penetrating the tight-knit dockworker and longshoremen communities (Fitzgerald, 2021).

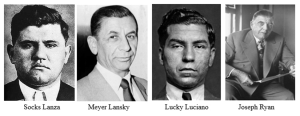

ONI Commander Charles R. Haffenden, based in New York, spearheaded Project Underworld, setting up headquarters in the Times Square Astoria Hotel. The ODI sought to contact the “czar” of Manhattan’s Fulton Fish Market, Joseph “Socks” Lanza. (Peduto, 2009) In order to reach out to Lanza, who, along with a lawyer, Haffenden, reached out to Joseph “Socks” Lanza, an influential Mafia-connected leader at the Fulton Fish Market. Lanza’s Control over longshoremen gave him unparalleled access to waterfront activity. To reach out to Lanza, who would never be seen communicating directly with law enforcement or the military, they decided to contact his attorney, Joseph Guerin. Guerin set up a clandestine meeting, and eventually, the Navy collected limited intelligence.

Lanza and other mob informants provided intelligence on suspicious activities, potential saboteurs, and movements along the docks. This significantly bolstered port security. ONI categorized their contributions as critical to safeguarding supply routes. To cross all the ethnic players on the docks, Sicilian boss “Lucky” Luciano was eventually contacted. However, Jewish boss Meyer Lansky, who secured the cooperation of Irish Longshoreman leader Joseph Ryan, was also involved. According to another Longshoreman leader, Jerry Sullivan, “Lansky was solving the problem for the Navy on the waterfront by the visible deployment of some of the most ruthless gangsters in the city. It was expected that the mere appearance of these men on the piers would serve as a deterrent, a warning to cooperate with the United States war effort or face the consequences.” (Peduto, 2009)

Project Underworld is credited with preventing sabotage, maintaining dockworker cooperation, and securing troop and supply shipments from hostile interference. The operation illustrates how, in times of existential threat, US security agencies sometimes leveraged unconventional—and ethically controversial—alliances to protect critical infrastructure.

Post-War to Cold War: Nuclear Security and Strategic Cargo Control

Defense Production Act of 1950 – Allowed Control of cargo priorities at ports during national emergencies. Ports began screening for strategic goods that could be exported to adversary nations, especially during the Korean War and the early Cold War period. Harbor Defense Commands integrated Army, Navy, and Coast Guard units to protect against potential Soviet naval threats.

Late 20th Century: Terrorism, Drug Smuggling, and Environmental Laws

Port and Waterways Safety Act of 1972 – Expanded Coast Guard authority to control vessel traffic and prevent marine accidents, incorporating environmental spill prevention into port security.

Maritime Drug Law Enforcement Act (1980) – Strengthened Coast Guard interdiction powers for narcotics trafficking through ports. Omnibus Diplomatic Security and Antiterrorism Act (1986) – Introduced measures to harden port facilities against terrorist attacks. (Congress N.-N., 1986) Oil Pollution Act of 1990 – Required ports to have spill prevention and emergency response plans, integrating environmental safety into security operations.

The 20th Century Shift

From 1900 to 2000, US port security evolved from a focus on customs, immigration, and public health into a comprehensive maritime security regime capable of responding to threats from military operations, smuggling, organized crime, public health and environmental disasters, terrorism, and sabotage. The Coast Guard, acting under a growing body of legislation, became the central enforcer, coordinating with customs, immigration, public health, and military authorities.

September 11, 2001

The events of September 11, 2001, caused a paradigm shift in US port security. Prior to 9/11, maritime security focused on safety and facilitating commerce; however, the attacks necessitated a reexamination of the risk and vulnerability of the Homeland. The first attacks upon US soil since Pearl Harbor and the Aleutians demanded a top-to-bottom review of port governance and security.

Legal Considerations

4th Amendment issues arose from the increased use of human and technological surveillance. Courts stressed that such activities must be reasonable and proportionate to the circumstances, and that a keen eye should be focused on governmental activities and regulations to guard against encroachment on fundamental rights.

The Supremacy Clause

States may impose additional port regulations, raising concerns about federal preemption. Federal preemption means that when federal and State laws conflict in an area where the US Constitution grants Congress authority, the federal law prevails over the state law. In port security, the basis for federal authority comes from the Commerce Clause (Article I, Section 8) and the Supremacy Clause (Article VI). Congress regulates commerce with foreign nations, among the states, and with Indian tribes—this includes navigation, shipping, and port operations. Under the Supremacy Clause, Federal law is “the supreme Law of the Land.” When valid federal port security statutes preempt conflicting State or local regulations, surveillance and cyber tools evolve, it is essential to remember that the government must also guard civil liberties.

Cybersecurity Risk

Ships, Planes, Trains, and Intermodal vehicle ports have become high-value targets for cybercriminals, hostile nations, hostile nation-states, and non-nation-state actors. Recent ransomware attacks have disrupted port management systems, cargo tracking platforms, and access controls, all causing significant disruptions. (Offshore Cyber, 2024)

Autonomous Technologies

The rise of drones, autonomous surface vessels, and AI-powered logistics platforms introduces new regulatory and operational challenges. Legal uncertainties include Jurisdiction over unmanned maritime and aerial operations, liability in cases of collisions or system failures, and data protection for onboard AI systems collecting surveillance or cargo data. (Maritime Fairtrade, 2025)

Conclusions

From the Revolutionary Era’s improvised naval militias, privateers, and ad hoc port defenses to today’s integrated, technology-driven maritime security systems, US port security has evolved through a steady layering of military, regulatory, and legal frameworks. Early port regulation emerged from British mercantilist laws and colonial resistance, giving way to the Continental Navy, the Revenue Cutter Service, and the formation of the US Navy.

Over time, federal authority expanded through customs enforcement, selective trade restrictions like the Non-Intercourse Act, wartime port closures during the War of 1812, and the Civil War. A broadening network of health, immigration, and anti-smuggling laws in the late 1800s and early 1900s required greater physical, technological, and human assets.

In the 21st century, ports have become critical infrastructure not only for commerce and defense but also as high-value targets for cybercriminals and nation-state actors. Recent ransomware attacks on port management systems, cargo tracking platforms, and access controls have compelled the US to integrate cybersecurity into its traditional maritime security model, which is now supported by Coast Guard regulations and executive mandates.

Although the threats from colonial days to the modern era have changed, the task of safeguarding America’s ports remains constant: to protect the nation’s economic lifelines and ensure that its maritime gateways remain secure, resilient, and under effective federal authority.

Questions To Consider

- How did early British maritime laws, such as the Navigation Acts and the Prohibitory Acts, shape colonial attitudes toward sovereignty and contribute to the origins of US port security?

- In what ways did the Revolutionary War’s reliance on privateers and ad hoc defenses set a precedent for later US approaches to blending private initiative and federal authority in maritime security?

- What lessons from the War of 1812 and Civil War demonstrate the shift from local, decentralized port defenses to federally coordinated, large-scale maritime enforcement?

- How did 19th- and 20th-century public health, immigration, and customs laws expand the definition of “port security” beyond military defense to include economic and social regulation?

- Given modern ransomware attacks and cyber threats targeting port infrastructure, how do contemporary challenges compare with historical threats (such as smuggling, piracy, and sabotage), and what does this reveal about the continuity of vulnerabilities in port systems?

References

Annals of Congress. (1817, January). Bill for Enforcing Neutrality. Retrieved from January 24, 1817, Volume 30, Pages 741 – 742 — Annals of Congress: https://www.congress.gov/annals-of-congress/page-headings/14th-congress/bill-for-enforcing-neutrality/39991.

British Parliament. (1775, December 22). American Legal History to the 1860s. Retrieved from Ch. 1.8. Primary Source: The Prohibitory Act, Dec., 1775: https://wisc.pb.unizin.org/ls261/chapter/ch-1-4-the-prohibitory-act-dec-1775/

Clarke, W. B. (1966). Journal of the Continental Congress, November 25, 1775. Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Vol. 2 (pp. 1131–1133). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Command, N. H. (2019, March 20). President Washington Signs the Naval Act of 1794. Retrieved from Naval History and Heritage Command: https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/heritage/origins-of-the-navy/washington-naval-act-1794.html

Congress, L. o. (1776, April 3). Instructions to the commanders of private ships or vessels of War, which shall have commissions or letters of marque and reprisal, authorising them to make captures of British vessels and cargoes. Retrieved from Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/resource/bdsdcc.00901/?st=gallery

Congress, N.-N. (1986, August 27). H.R.4151 – Omnibus Diplomatic Security and Antiterrorism Act of 1986. Retrieved from Congress.gov: H.R.4151 – Omnibus Diplomatic Security and Antiterrorism Act of 1986

Congress, S.-T. (1915, January 28). Act to create the Coast Guard. Retrieved from Legisworks: https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/38/STATUTE-38-Pg800.pdf

Congress, U. S. (1789, July 4). Tariff of 1789. Retrieved from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: https://www.usitc.gov/publications/other/pub0000.pdf

Dobson, J. M. (1976, December). Two Centuries of Tariffs: The Background and Emergence of the US International Trade Commission. Retrieved from United States International Trade Commission: https://www.usitc.gov/publications/other/pub0000.pdf

Ellis Island. (2025, August 2). Retrieved from The Statue of Liberty – Ellis Island Foundation, Inc.: https://www.statueofliberty.org/ellis-island/overview-history/

Fifty-first Congress. (1891, March 3). CHAP. 551.—An act in amendment to the various acts relative to immigration. Retrieved from Congress: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-26/pdf/STATUTE-26-Pg1084-2.pdf#page=1

Fitzgerald, C. (2021, October 25). Project Underworld: The US Navy’s Unexpected Mafia Alliance. Retrieved from War History Online: https://www.warhistoryonline.com/instant-articles/project-underworld-us-navys-unexpected-mafia-alliance.html

Forty-Fifth Congress. (1878, April 23). An Act to prevent the introduction of contagious or infectious diseases, April 29, 1878. Retrieved from Congress.gov: An Act to prevent the introduction of contagious or infectious diseases, April 29, 1878.

Hamilton, A. (1987, November 27). Federalist Papers: Primary Documents in American History. Retrieved from Library of Congress: https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/text-11-20

International Longshoremen’s Association. (2021, August 12). ILA-USMX Joint Safety Committee. Retrieved from International Longshoremen’s Association: https://ilaunion.org/2021/08/page/2/

Lincoln, President Abraham. (1861, April 15). Abraham Lincoln, Monday, April 15, 1861 (Proclamation on State Militia). Retrieved from United States Senate: https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/civil_war/LincolnExtraordinarySession_Transcript.htm

Madison, P. J. (1812, June 19). Presidential Proclamation, [June 19] 1812. Retrieved from National Archives: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/03-04-02-0517

McCay, W. (1917). Must liberty’s light go out? Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Retrieved August 5, 2025, from National Constitution Center: https://www.loc.gov/item/96519622/.

Norton, L. A. (2019). War at Sea and Waterways (1775–1783). Journal of the American Revolution.

Peduto, G. (2009, November). Project Underworld: The US Navy’s Secret Pact with the Mafia. Retrieved from Warfare History Ne#: ~rk: https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/project-underworld-the-u-s-navys-secret-pact-with-the-mafia/#:~:text=Director%20of%20Naval%20Intelligence%2C%20Rear,hunt%20down%20the%20guilty%20party.

Roosevelt, P. F. (1942, February 25). Executive Order 9074—Directing the Secretary of the Navy to Take Action Necessary to Protect Vessels, Harbors, Ports, and Waterfront Facilities. Retrieved from The American Presidency Project: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-9074-directing-the-secretary-the-navy-take-action-necessary-protect

Sixty-Fifth Congress. (2017, June 15). An Act to punish acts of interference. Retrieved from Espionage Act of 1917: https://loveman.sdsu.edu/docs/1917EspionageAct.pdf

Sixty-sixth Congress of the United States. (1919, May 19). The Volstead Act. Retrieved from https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/Volstead_1.pdf

SUNY Maritime College. (2025, August 1). SUNY Maritime- Fort Construction. Retrieved from SUNY Maritime College: https://www.sunymaritime.edu/about-suny-maritimehistory/fort-schuyler-history

Trust, A. B. (n.d.). The Turtle. Bushnell’s Turtle: A Revolutionary Submarine. American Battlefield Trust, Washington, D.C.

United States Coast Guard. (2022, March 10). Eagle, 1809. Retrieved from United States Coast Guard: https://www.history.uscg.mil/Browse-by-Topic/Assets/Water/All/Article/2962022/eagle-1809/

United States Congress. (1807, December 22). Acts of the Tenth Congress. Retrieved from Library of Congress: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llsl//llsl-c10/llsl-c10.pdf

United States Congress. (1809, June 1). June 6, 1809, Volume 20, Pages 27 – 28 — Annals of Congress. Retrieved from Congress.gov: https://www.congress.gov/annals-of-congress/page-headings/11th-congress/non-intercourse/31719

United States Congress. (1819, March 3). An Act to protect the commerce of the United States, and punish. Retrieved from History of the Navy: An Act to protect the commerce of the United States, and punish

United States Navy. (2017, November 6). Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved from Resolution of the Continental Congress, November 25, 1775: https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/r/resolution-of-the-continental-congress-25-november-1775.html