11 Sea of Risk (Murthy)

Abbreviations

CMTSR – Canada’s Marine Transportation Security Regulation,

CSO – Company Security Officers

EUMMS – EU initiatives under the EU Maritime Security Strategy

ISPS – International Ship and Port Facility Security Code

MTSA – US Maritime Transportation Security Act

PFSO – Port Facility Security Officers

SOLAS Safety of Life at Sea

SSO – Ship Security Officers

SUA Convention – (Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation)

Terminology

Sea of Risk – the fragile, tightly coupled system of systems that defines modern maritime security.

STRATOS – Strategic Thinking and Resilience Across Tactics, Outcomes, and Systems.

TTM – Trans dimensional Thinking Model (cognitive clarity).

OSSTE – Operational Systems for Security, Tactics, and Execution (operational structure).

Student Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, students will be able to develop and evaluate strategic maritime defense frameworks using cognitive, operational, and systems-based approaches for complex, converging threat environments.

- Understand the dimensions and complexities of securing maritime systems

- Assess gaps in current maritime defense strategies from a holistic perspective related to organizational culture, continuity, and capital

- Identify the components and functions of STRATOS

- Develop actionable recommendations to enhance strategic maritime resilience.

Sea of Risk

The sea has always carried risk. From piracy and storms to geopolitical tensions and smuggling, maritime activity has long demanded vigilance, coordination, and resilience. But in today’s hyperconnected world, maritime risk has transformed. What once were localized threats can now ripple across the globe — paralyzing ports, compromising data, or choking supply chains.

This is the new Sea of Risk: a complex, multidimensional maritime stratosphere where digital, physical, and human vulnerabilities intersect. Cyberattacks against port operations can strand billions in trade overnight(LLo, 2019). GPS spoofing can send ships off course, jeopardizing safety and sovereignty(Andringa et al., 2025; World Ports, 2025). Insider threats, hacktivism, or criminal networks can weaponize data streams as readily as contraband(Grispos & Mahoney, 2022). These risks are no longer contained at sea; they manifest simultaneously on networks, in infrastructure, and through people.

In this environment, containerized trade is as much about packets of data as it is about tons of cargo. Ports operate as critical digital ecosystems, dependent on logistics software, satellite navigation, and automated cranes that now fall within the scope of cyber defense(LaRocco, 2024). Maritime security has expanded from escorting vessels and policing waters to defending code, algorithms, and information pathways. The adversaries no longer fit a single profile; they are nation-states seeking disruption, criminal syndicates pursuing profit, and activist groups driving ideological agendas(Burgess, 2017; Triebert et al., 2023).

What emerges is not a linear chain of vulnerabilities but an interwoven mesh of risks. A ransomware attack on a regional terminal can ripple into global financial markets(LLo, 2019). A supply chain compromise in one port can destabilize downstream industries across continents. Even misinformation about a maritime incident can fuel geopolitical crises. The sea, once a barrier between nations, is now a backbone of global interdependence, and its fragility lies as much in servers and sensors as in hulls and harbors.

Understanding Maritime Security

Maritime security is often misunderstood as a narrowly defined concept — limited to protecting ships from piracy or ensuring port safety. In reality, it is multidimensional, cutting across a complex web of concerns: governance, economy, environment, defense, law enforcement, safety, and response and recovery.

These dimensions are not isolated. Instead, they function as interdependent layers that shape the operational, strategic, and policy landscape of maritime activity. A failure in one domain — such as a regulatory loophole or an environmental hazard — can quickly escalate, impacting others and triggering broader systemic consequences.

Consider the scale and complexity of the maritime industry[3]:

- It moves over 90% of global trade by volume(Shipping Data, 2025).

- It is a critical node for military power projection and defense readiness(Maritime Security, n.d.).

- It plays a major role in fisheries, energy transport, undersea infrastructure, and environmental protection(Maritime Security, n.d.).

- It must respond not only to intentional threats like smuggling, piracy, or terrorism, but also to non-malicious disruptions like climate events, mechanical failures, and crew shortages(Canada, n.d.).

Because of this complexity, maritime security cannot rely solely on technology or defense assets. It must be systemic, involving supervision, inspections, training, enforcement, and most importantly — a culture of proactive risk awareness. Moreover, the actors responsible for security are diverse: national governments, coast guards, shipping companies, private port operators, customs officials, insurers, environmental regulators, and cyber defense teams, each with different mandates and constraints(Maritime Security, n.d.).

To fully appreciate how these moving parts fit together, it helps to view maritime security through its seven critical dimensions. Each dimension is strategically vital, but also carries its own vulnerabilities and policy levers for strengthening resilience(Gu & Liu, 2025; Thai, 2009):

Governance

- Strategic Importance: Provides the rules, norms, and legal frameworks that guide maritime conduct and cooperation.

- Key Risks & Vulnerabilities: Regulatory loopholes, weak flag-state enforcement, fragmented jurisdiction, corruption, and gaps in international law.

- Policy & Strategic Levers: Strengthen UNCLOS-based agreements; close legal gaps; harmonize regulations; increase multilateral information-sharing and compliance mechanisms.

Economy & Trade

- Strategic Importance: Backbone of global commerce, with over 90% of trade transported by sea (Shipping Data, 2025).

- Key Risks & Vulnerabilities: Supply chain disruption, port shutdowns, cyberattacks on logistics systems, trade manipulation, and insurance vulnerabilities.

- Policy & Strategic Levers: Build resilient trade corridors; require cybersecurity standards for logistics providers; diversify critical supply chains; develop public-private resilience compacts.

Environment

- Strategic Importance: Shipping impacts and depends on ecological stability, fisheries, and climate resilience.

- Key Risks & Vulnerabilities: Oil spills, ballast water transfer of invasive species, extreme weather events, sea-level rise disrupting ports, and illegal fishing practices.

- Policy & Strategic Levers: Implement green shipping standards; invest in climate adaptation infrastructure; enhance monitoring of IUU fishing; integrate environmental security in maritime strategies.

Defense & Geopolitics

- Strategic Importance: Sea lanes are strategic arteries for power projection and military deterrence.

- Key Risks & Vulnerabilities: Freedom of navigation threats, militarization of disputed waters, hybrid warfare (NATO, 2021), sabotage of undersea cables or energy corridors.

- Policy & Strategic Levers: Multinational naval exercises; defense-cyber integration; diplomatic frameworks for contested waters; protect maritime critical infrastructure.

Law Enforcement & Crime

- Strategic Importance: Prevents illicit flows of goods, people, weapons, and data through maritime routes.

- Key Risks & Vulnerabilities: Piracy, human trafficking, narcotics smuggling, arms proliferation, dark shipping (AIS spoofing), cyber-enabled smuggling.

- Policy & Strategic Levers: Strengthen joint maritime task forces; enhance maritime domain awareness; criminalize cyber-enabled crimes at sea; improve customs–cyber intelligence fusion.

Safety & Human Factors

- Strategic Importance: Protects crews, passengers, and port workers while maintaining operational integrity.

- Key Risks & Vulnerabilities: Accidents, training shortfalls, fatigue-related mishaps, reliance on aging vessels, crew exploitation, and mental health stress.

- Policy & Strategic Levers: Mandate continuous safety training; improve human factor integration in automation; enhance labor rights oversight; incentivize safety-driven technologies.

Response & Recovery

- Strategic Importance: Core pillar of resilience, enabling restoration of maritime operations after disruption.

- Key Risks & Vulnerabilities: Fragmented crisis response across jurisdictions, slow recovery from cyber or physical incidents, inadequate continuity planning.

- Policy & Strategic Levers: Establish multinational rapid-response frameworks; exercise cyber/physical disaster simulations; implement resilience-by-design protocols; bolster insurance and reinsurance mechanisms tied to compliance.

This multidimensional view underscores that maritime security must be conceived not as a collection of discrete challenges, but as a strategic ecosystem. Governance gaps can enable economic disruption; environmental shocks can strain defense readiness; cyber incidents in logistics can complicate law enforcement. The interconnections mean that resilience in one area is inseparable from resilience in others.

What follows, then, is the core challenge for policymakers and industry leaders: to design frameworks that are broad enough to capture the complexity of these dimensions, yet deep enough to provide actionable direction amid uncertainty. A single set of threats does not define the Sea of Risk, but by how these seven dimensions interact — and how effectively states, industries, and institutions can coordinate to safeguard them.

Maritime Systems: Mainland and Transportation

This chapter proposes that maritime security, when viewed holistically, maritime security can be understood as operating within two primary components: mainland maritime systems and maritime transportation systems. These are interconnected yet distinct domains, each with its own priorities, actors, and vulnerabilities.

- Mainland Maritime Systems are largely national in orientation, tied to coastal zones, ports, harbors, shipyards, and supporting infrastructure. Here, the dominant priorities are national security and public safety — ensuring territorial sovereignty, protecting critical maritime infrastructure, and regulating activity within inland or coastal boundaries.

- Maritime Transportation Systems, by contrast, are global by nature. They are composed of vessels, crews, and cargo flows that continually traverse international waters, linking continents and economies. In this domain, resilience of supply chains and logistics takes precedence over territorial defense. The operational challenge extends far beyond borders, demanding international cooperation, risk management, and cross-industry collaboration.

A short comparison[4] of the maritime mainland and transportation systems is given below:

Governance: At the mainland level, governance is enacted through national regulations, port authority compliance, customs enforcement, zoning laws, and coastal management. At the global level, maritime transportation systems are shaped by international conventions such as UNCLOS and IMO frameworks, flag-state rules, and port-state controls, which often create jurisdictional overlaps.

Economy & Trade: At the local level, the economy and trade dimension focuses on port security, domestic trade facilitation, customs integrity, and the smooth functioning of critical industries such as energy terminals and fisheries. At the global scale, it emphasizes supply chain resilience, shipping route security, vessel scheduling, and insurance considerations across multiple jurisdictions.

Environment: Environmental concerns locally are managed through coastal resilience measures such as oil spill response, shoreline protection, and pollution controls, alongside environmental enforcement within territorial waters. Globally, the focus shifts to open-ocean challenges, including fuel emissions compliance, ballast water impacts, marine biodiversity protection, and climate stress on long voyages.

Defense & Geopolitics: National defense and geopolitical concerns involve protecting critical infrastructure such as ports, shipyards, and naval bases, and asserting sovereignty within exclusive economic zones (EEZs). At the global level, the emphasis lies on freedom of navigation operations, chokepoint security at straits and canals, vessel protection against state and non-state adversaries, and naval escort missions.

Law Enforcement & Crime: Locally, law enforcement focuses on policing ports and coastal areas, interdicting smuggling, managing inspection regimes, and responding to trafficking and irregular migration. On the global stage, priorities include piracy deterrence, detecting AIS spoofing, inspecting container cargo en route, and conducting anti-trafficking patrols in international waters.

Safety & Human Factors: Local safety concerns emphasize protecting workers in ports, such as stevedores, inspectors, and dock crews, along with harbor pilot coordination and emergency services. Globally, safety and human factors address crew training, fatigue management, seafarer welfare, labor exploitation risks, and ensuring safe vessel operation under extreme conditions.

Response & Recovery: At the national level, response and recovery involve disaster management for hurricanes, infrastructure disruptions, and cyberattacks on port IT systems, while ensuring continuity of domestic logistics. At the global level, they include rerouting shipping lanes, recovering vessels mid-transit, and fostering international cooperation to support stranded or hijacked ships.

Both systems are populated by a mix of state and non-state actors:

- Nations (state actors) set policies, naval doctrines, and regulatory frameworks.

- Corporates (non-state actors) operate ports, vessels, and logistics networks, holding much of the operational responsibility.

- Illicit actors — pirates, smugglers, traffickers — exploit system seams and jurisdictional blind spots.

- Attackers, both state-sponsored and independent, target vulnerabilities in infrastructure, vessels, or data flows for strategic gain or disruption.

Much of modern maritime defense is thus designed as a shield for operations, ports, cargo, and coastal environments against a broad spectrum of threats: terrorism, piracy, organized crime, cyberattacks, smuggling, and illegal trafficking. But how this shield is built, and where resources are concentrated, varies widely across nations and regions.

Divergence and Convergence in Maritime Transportation Strategies

Maritime transportation security strategies share many global principles — surveillance, risk management, international cooperation — but their focus and implementation differ significantly by country or region(Bichou et al., 2014; Indian Navy Directorate of Strategy, Concepts and Transformation, 2015). Geography, geopolitical posture, dependency on maritime commerce, and local threat landscapes all shape strategy(Germond, 2015; UNTAD, 2024). A Gulf shipping lane faces pressures unlike an Arctic passage; a major naval power views security differently than an export-dependent island nation(Pratson, 2023; Thakur, 2024).

Below is a consolidated view of how major countries and blocs align on maritime transportation security[5]:

Australia (Australia Department of Home Affairs, 2022)

- Main Priorities: Protect sea lines of communication, secure ports, counter-piracy, and environmental protection in fragile zones.

- Unique Aspects: Strong Indo-Pacific partnerships; intense focus on biosecurity and environmental safeguards.

Brasil (Brasileiro da Cibersegurança, 2020; Brazil Presidency, n.d.; Marinha do Brasil, n.d.)

- Main Priorities: Security of coastal trade routes, monitoring of offshore oil platforms, combating smuggling/trafficking.

- Unique Aspects: Heavy emphasis on Blue Amazon (exclusive economic zone) and resource security.

Canada (Canada, n.d.; Crickard, 1995)

- Main Priorities: Arctic sovereignty, maritime safety, environmental resilience, and defense integration with NATO.

- Unique Aspects: Arctic domain awareness as a cornerstone; environmental sustainability heavily embedded.

China[6]

- Main Priorities: Sea lane security, military projection, trade corridor protection (Belt and Road), and fishing fleet protection.

- Unique Aspects: Combines commercial maritime security with military power projection; aggressive construction of dual-use ports.

European Union[7]

- Main Priorities: Integrated maritime surveillance, port/cargo security, sustainability, and anti-smuggling.

- Unique Aspects: Emphasis on EU-wide coordination and environmental standards; legal frameworks for integration.

India[8]

- Main Priorities: Coastal surveillance, anti-piracy patrols, protection of energy imports, counterterrorism.

- Unique Aspects: Focus on Indian Ocean chokepoints, naval-civil integration.

Russia[9]

- Main Priorities: Arctic and Black Sea dominance, maritime power projection, energy supply protection.

- Unique Aspects: Militarized approach to shipping and infrastructure; dual-use emphasis with limited international transparency.

United Kingdom[10]

- Main Priorities: Trade resilience, anti-terrorism, and port infrastructure protection.

- Unique Aspects: Heavy focus on intelligence-sharing and NATO naval coordination; combined civilian-defense emphasis.

United States[11]

- Main Priorities: Global sea lane security, counterterrorism, cyber defense, freedom of navigation, and port resilience.

- Unique Aspects: Worldwide naval policing role; wide-ranging public-private partnerships in port and logistics system security.

This comparative view underscores how shared threats like smuggling, domain awareness, and cyber vulnerabilities manifest differently depending on geography, economic reliance, and political posture.

States Versus Corporations: Dual Lenses of Maritime Security

One of the defining complexities of maritime security lies in the different ways that states and corporations view and operationalize risk[12].

- For states, maritime security is first and foremost about sovereignty, defense, and compliance. They view threats in terms of geopolitical balance, law enforcement, environmental stewardship, and resilience against adversaries. Investments flow into coast guards, navies, customs, and regulatory enforcement regimes.

- For corporations, particularly shipping companies, port operators, and insurers, the lens is different. Security is framed around business continuity, liability, financial exposure, and operational resilience. Downtime equals economic loss. A cyber breach, cargo delay, or reputational hit is often more pressing than geopolitical maneuvering. Corporates therefore prioritize real-time monitoring, cybersecurity, risk management frameworks, and contractual assurances.

Increasingly, both perspectives must converge in practice. A state cannot secure national waters without private compliance and technological support. Corporates cannot operate securely in volatile waters without state naval presence or legal enforcement. The line between public goods (security, law, defense) and private imperatives (profit, efficiency, insurance mitigation) is thinner at sea than anywhere else.

It is this duality — mainland systems anchored in national public safety, and transportation systems propelled by global commercial resilience — that forms the backbone of maritime security. Any strategic framework that divorces one from the other risks leaving the system exposed to cascading shocks.

Governance & Regulation

- State View (Nations): Upholding sovereignty, enforcing territorial laws, regulating ports and EEZs, and negotiating international treaties (UNCLOS, IMO, bilateral agreements).

- Corporate View (Operators, Ports, Insurers): Compliance with international codes (ISPS, IMO), flag-state rules, contractual obligations, and using compliance as risk mitigation and legitimacy.

Defense & Security

- State View (Nations): Protect sea lanes, deter piracy and terrorism, project naval power, and safeguard undersea cables/energy corridors.

- Corporate View (Operators, Ports, Insurers): Avoid high-risk regions through route planning, contract private security or armed guards, and adopt vessel hardening and surveillance technologies.

Economy & Trade

- State View (Nations): Secure national trade flows, protect exports/imports, support GDP and energy security, safeguard national critical maritime infrastructure.

- Corporate View (Operators, Ports, Insurers): Maintain supply chain continuity, minimize downtime, reduce financial loss and liability, protect cargo integrity, and assure clients/insurers of reliability.

Cybersecurity & Digital Systems

- State View (Nations): Guard critical national infrastructure (ports, customs, undersea cables, naval IT), regulate standards for domestic systems.

- Corporate View (Operators, Ports, Insurers): Secure vessel navigation tech, port IT systems, cargo management platforms, and communications; build resilience against ransomware and system delays.

Environment & Sustainability

- State View (Nations): Enforce environmental regulations (emissions, ballast water, fisheries), protect coastal ecosystems, and climate adaptation.

- Corporate View (Operators, Ports, Insurers): Compliance with emissions and ballast rules, implementing green shipping practices for efficiency and reputational advantage; managing insurance exposure to environmental risks.

Law Enforcement & Crime

- State View (Nations): Counter smuggling, human trafficking, narcotics, terrorism, and enforce customs and maritime policing.

- Corporate View (Operators, Ports, Insurers): Implement container security protocols, deploy digital cargo monitoring, ensure compliance to reduce reputational and financial risk; cooperate with law enforcement when needed.

Safety & Human Factors

- State View (Nations): Regulate seafarer labor, enforce safety at sea, fund coast guard/port inspections, and establish crew welfare requirements.

- Corporate View (Operators, Ports, Insurers): Train crews, manage fatigue, adopt safety culture, and mitigate labor risks (strikes, exploitation) to maintain operational reliability.

Response & Recovery

- State View (Nations): Coordinate disaster response, national emergency services, international crisis diplomacy, and naval/coast guard mobilization.

- Corporate View (Operators, Ports, Insurers): Maintain insurance coverage, crisis management plans for hijacking or cyber incidents, reroute vessels, and restore operations for minimal business disruption.

Major Frameworks and Standards

A mosaic of international frameworks, treaties, conventions, and national legislations underpins maritime security today. These instruments are the scaffolding that both states and corporates rely upon to operationalize security. However, while they provide a global foundation, many exist in parallel silos, with uneven enforcement and interoperability challenges across jurisdictions.

International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS)[13] Code

- A comprehensive mandatory regime under Chapter XI-2 of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), 1974.

- Establishes international standards for governments, port authorities, and shipping companies to identify threats and implement preventive measures.

- Requires designating Port Facility Security Officers (PFSOs), Ship Security Officers (SSOs), and Company Security Officers (CSOs).

- Part A sets mandatory requirements, Part B offers guidance and best practices.

SOLAS Convention (International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea)

- The foundational treaty on the safety and security of merchant ships.

- Post-9/11, Chapter XI-2 was added to integrate maritime security provisions, forming the legal backbone for the ISPS Code.

SUA Convention (Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation)[14]

- Criminalizes unlawful acts threatening maritime safety: hijacking, sabotage, terrorism, and the transport of weapons of mass destruction by ship.

- Provides an international legal basis for prosecuting maritime terrorism and sabotage.

IMO Cybersecurity Guidelines[15]

- High-level guidelines adapting traditional safety/security standards to the digital domain.

- Encourage states and companies to integrate cyber risk management into vessel and port security planning.

- Increasingly referenced as mandatory in regulatory audits and insurance assessments.

National and Regional Legislation

- Countries reinforce and expand global standards with domestic maritime security acts.

- Examples include the US Maritime Transportation Security Act (MTSA), Canada’s Marine Transportation Security Regulations, and EU initiatives under the EU Maritime Security Strategy (EUMSS).

- These often introduce additional compliance and reporting burdens, resulting in a patchwork of overlapping requirements across nations.

These instruments collectively form the backbone of maritime transportation security, but they remain fragmented, compliance-driven, and reactive. States often focus on enforcement, corporates on compliance, leaving gaps in integration: cyber risk, supply chain interconnectivity, and real-time intelligence sharing are still weak points. The challenge is not a lack of frameworks, but the siloed application of them — each solving part of the problem, but rarely creating a holistic architecture.

Challenges in a Multidimensional Maritime Environment

As discussed in previous sections, the maritime environment is often imagined as vast and resilient — a boundless blue expanse, able to absorb shocks and reroute flows with little friction. But in reality, the maritime stratosphere that underpins global trade is remarkably fragile: deeply interconnected, layered with critical systems, and vulnerable to cascading risks.

Today’s maritime domain can be seen as a system of systems:

- Physical systems: ships, ports, bridges, and inland logistics.

- Digital systems: port IT, satellite navigation, vessel AIS, and automation algorithms.

- Human systems: crews, port workers, inspectors, and emergency responders.

- Regulatory systems: customs processes, insurance, and jurisdictional enforcement.

Each of these subsystems is tightly interwoven. A disruption in one can cascade into others — amplifying the impact far beyond the original incident site.

Case 1: Baltimore Bridge Collapse (2024)

When a container vessel veered off course and struck the Francis Scott Key Bridge, the result was the collapse of a critical transit artery. What seemed like a localized physical incident quickly rippled across multiple domains:

- Logistics: Immediate shutdown of the Port of Baltimore disrupted East Coast flows.

- Inland transport: Rerouting strained rail and trucking networks.

- Legal/financial: Insurance claims and liability disputes cascaded across international jurisdictions.

- Cyber-physical vulnerability: Questions arose about navigation system resilience, leading to stricter scrutiny of vessel IT/OT (Information Technology/Operational Technology).

Despite its physical origin[16], the consequences were digital, legal, logistical, and economic — a textbook example of cascading failure in a coupled maritime ecosystem.

Case 2: Black Sea Incidents (2017–present)

Maritime disruptions in contested waters like the Black Sea illustrate how geopolitical and hybrid risks can converge[17]:

- Electronic warfare and GPS spoofing placed vessels at risk by manipulating their navigation.

- Naval blockades and targeted attacks turned shipping routes into leverage in geopolitical conflicts.

- Insurance premiums and freight costs skyrocketed, reflecting systemic market fears.

This shows how military, economic, and digital layers collide in contested maritime zones — echoing the multidimensionality of today’s threats.

Case 3: NotPetya Cyberattack (2017)

Though not maritime-specific in origin, NotPetya exposed the cyber fragility of global shipping in stark terms.

- Maersk, the world’s largest container carrier, lost control of its IT infrastructure in offices across the countries it operates.

- Terminal operations ground to a halt worldwide, stranding thousands of containers.

- Estimated costs exceeded $300 million.

The lesson was clear[18]: logistics chains are highly efficient but barely resilient. When digital visibility breaks, the entire flow collapses.

What These Incidents Teach Us

These are not anomalies. They are signals — warnings that the maritime domain now exists in a state of entangled risk, where disruptions in any single domain reverberate across the system. Key patterns include:

- Tightly coupled systems: Failures cascade like dominoes once one link breaks.

- Cyber-physical fusion: A digital breach can trigger physical chaos, and physical events spark digital or legal fallout.

- Lack of redundancy: Efficiency has overtaken resilience, leaving no slack to absorb shocks.

- Strategic blindness: Decision-makers often lack visibility into adjacent systems they depend on.

The Sea of Risk: Anticipation Over Reaction

This is the essence of the modern Sea of Risk: dynamic, opaque, and unforgiving. Traditional reactive approaches — deploying naval forces, enforcing customs law, or patching IT systems — are insufficient when risks are interwoven across physical, digital, legal, and human layers.

Resilience in this environment requires:

- Anticipation: Proactively identifying risks across multiple dimensions before they cascade.

- Integration: Bridging siloed frameworks, actors, and domains to create cohesive defenses.

- Strategic fluency: A policymaker’s and operator’s ability to “speak across systems” — law, cyber, logistics, and human factors — to navigate a multidimensional maritime ecosystem.

In short, the Sea of Risk demands not just new tools, but a new mindset: one of systemic thinking, cross-domain collaboration, and resilience-by-design.

Dimensions × Disciplines in Maritime Security

Maritime security must be understood both in terms of dimensions (the operational and spatial domains where risks emerge — surface, subsea, cyber, space, etc.) and disciplines (the fields of expertise and practice — law, engineering, cybersecurity, economics, etc. — that address them). While each dimension has unique challenges and each discipline offers specialized insight, the true complexity of the Sea of Risk lies in how they interlock. Mapping dimensions to disciplines exposes where expertise converges, where silos persist, and where multidimensional, interdimensional, and transdisciplinary approaches are essential for resilience[19].

Surface (ships, ports, sea lanes)

- Key Risks & Focus Areas: Piracy, port security, cargo theft, smuggling, congestion, and safety.

- Relevant Disciplines (Who/What Expertise): Naval operations, international/maritime law, trade economics, logistics engineering, law enforcement.

Airspace (aircraft, UAVs over maritime zones)

- Key Risks & Focus Areas: Border surveillance, anti-smuggling, SAR (search and rescue), UAV monitoring, aerial piracy deterrence.

- Relevant Disciplines (Who/What Expertise): Aerospace engineering, defense studies, aviation law, border security, and data science for aerial surveillance.

Subsea (submarines, underwater drones, sensors)

Surface (ships, ports, sea lanes)

- Key Risks & Focus Areas: Piracy, port security, cargo theft, smuggling, congestion, and safety.

- Relevant Disciplines (Who/What Expertise): Naval operations, international/maritime law, trade economics, logistics engineering, law enforcement.

Airspace (aircraft, UAVs over maritime zones)

- Key Risks & Focus Areas: Border surveillance, anti-smuggling, SAR (search and rescue), UAV monitoring, aerial piracy deterrence.

- Relevant Disciplines (Who/What Expertise): Aerospace engineering, defense studies, aviation law, border security, and data science for aerial surveillance.

Subsea (submarines, underwater drones, sensors)

- Key Risks & Focus Areas: Submarine threats, underwater drones, sonar interference, and domain awareness gaps.

- Relevant Disciplines (Who/What Expertise): Naval architecture, oceanography, undersea acoustics, military strategy, cyber-physical systems engineering.

Seabed (cables, pipelines, undersea resources)

- Key Risks & Focus Areas: Sabotage of undersea cables, pipeline attacks, illegal seabed resource extraction, and environmental risk.

- Relevant Disciplines (Who/What Expertise): Energy security, marine geology, environmental science, critical infrastructure law, naval defense.

Cyber (digital networks, automation, port IT systems)

- Key Risks & Focus Areas: Ransomware, AIS spoofing, port system shutdowns, supply chain visibility loss.

- Relevant Disciplines (Who/What Expertise): Cybersecurity, info security governance, computer science, insurance risk modeling, international cyber law.

Space/LEO (satellites for comm/nav/surveillance)

- Key Risks & Focus Areas: GPS/GNSS spoofing, satellite jamming, communication disruption, space debris.

- Relevant Disciplines (Who/What Expertise): Space law, satellite engineering, data science, defense studies, and geopolitics of space infrastructure.

Seabed (cables, pipelines, undersea resources)

- Key Risks & Focus Areas: Sabotage of undersea cables, pipeline attacks, illegal seabed resource extraction, and environmental risk.

- Relevant Disciplines (Who/What Expertise): Energy security, marine geology, environmental science, critical infrastructure law, naval defense.

Cyber (digital networks, automation, port IT systems)

- Key Risks & Focus Areas: Ransomware, AIS spoofing, port system shutdowns, supply chain visibility loss.

- Relevant Disciplines (Who/What Expertise): Cybersecurity, info security governance, computer science, insurance risk modeling, international cyber law.

Space/LEO (satellites for comm/nav/surveillance)

- Key Risks & Focus Areas: GPS/GNSS spoofing, satellite jamming, communication disruption, space debris.

- Relevant Disciplines (Who/What Expertise): Space law, satellite engineering, data science, defense studies, and geopolitics of space infrastructure.

Understanding maritime security through this dimension–discipline map highlights that risks do not stay confined to a single domain or expertise. A ransomware attack (cyber) paralyzes ports (surface), disrupts cargo flows (economics), and cascades globally (law, insurance, geopolitics). These interdependencies show why siloed approaches fall short when navigating the sea of risk.

Cross-Cutting Threats in the Sea of Risk

Ransomware Attack on Port IT

- Dimensions Affected: Cyber (networks), surface (ports), Space/LEO (satellite comms if disrupted).

- Disciplines Required: Cybersecurity, computer science, port logistics, insurance, and international law.

- Why It Cross-Cuts: Halts cargo visibility, paralyzes port operations, and requires legal, technical, and financial expertise for recovery.

Piracy / Armed Robbery

- Dimensions Affected: Surface (ships, ports), airspace (surveillance), Subsea (boarding detection tech).

- Disciplines Required: Naval defense, maritime law, criminal justice, sociology (crew risk/training), trade economics.

- Why It Cross-Cuts: More than a law enforcement issue — also impacts insurance, crew welfare, and global shipping costs.

Climate Event (e.g., superstorm on a coastal hub)

- Dimensions Affected: Surface (ports, shipping), seabed (pipelines, cables), airspace (emergency response).

- Disciplines Required: Environmental science, civil engineering, economics, disaster management, and insurance risk modeling.

- Why It Cross-Cuts: Exposes fragile infrastructure; causes cascading environmental and logistical crises.

GPS Spoofing / Jamming

- Dimensions Affected: Space/LEO (satellites), Cyber (signal manipulation), Surface (vessel navigation).

- Disciplines Required: Satellite engineering, data science, defense strategy, and cyber forensics.

- Why It Cross-Cuts: Blurs military and civilian domains, forcing joint defense, tech, and international coordination.

Smuggling / Trafficking

- Dimensions Affected: Surface (ships, ports), Airspace (detection), Seabed (concealment routes: subs/cables).

- Disciplines Required: Law enforcement, customs/regulation, criminology, geopolitics, trade logistics.

- Why It Cross-Cuts: Undermines state control, finances criminal networks, and exploits weak governance nodes.

Hybrid State-Sponsored Attack (e.g., combining cyber + naval intimidation)

- Dimensions Affected: Cyber, Surface, Space/LEO, Seabed (cables), Airspace (UAVs).

- Disciplines Required: Cybersecurity, international law, naval strategy, geopolitics, and economics.

- Why It Cross-Cuts: Forces simultaneous response across domains and disciplines, collapsing traditional boundaries.

Some observations:

- No threat is one-dimensional: Even “classic” piracy involves naval defense (surface), aerial surveillance (airspace), logistics, economics, law, and insurance.

- Threats span dimensions at once: NotPetya (cyber) became a global supply chain (surface/economics) and legal liability (law/insurance) crisis.

- Hybridization is the norm, not the exception: Modern adversaries combine cyber and physical attacks, and economic/legal ripple effects amplify climate events.

- Response requires transdisciplinary coordination: Naval officers cannot solve insurance claims; cybersecurity experts cannot deploy naval patrols; environmental scientists cannot restore trade routes — yet all must align their expertise.

This matrix reinforces the central argument: maritime security cannot be siloed. It demands multidimensional vigilance, interdimensional integration, and transdisciplinary collaboration to anticipate and withstand the cascading shocks of the Sea of Risk.

Technological Evolution and Emerging Threats

The maritime industry is undergoing a rapid transformation(Alcaide & Llave, 2020; Azzab et al., 2024; Diaz et al., 2023). In pursuit of efficiency, cost savings, and environmental compliance, operators are embracing automation, digitalization, and smart systems at unprecedented speed. But with this evolution comes an expanded and often poorly understood threat surface.

Where once maritime risks stemmed from piracy or storms, they now emerge equally from malicious code, compromised satellites, or autonomous system failures(Bronk & deWitte, 2022; Li et al., 2024). The line between physical and digital threats is blurring, and the overlap expands the maritime threat environment faster than governance or preparedness can keep pace(Akpan et al., 2022; Ammar & Khan, 2024).

Automation and Autonomous Vessels

The rise of autonomous ships represents a paradigm shift(World Maritime University, 2019). These vessels, controlled by software, remote command centers, and machine learning, promise fewer errors, greener efficiency, and operation without traditional crews. Norwegian firms are already trialing fully remote-controlled cargo ships.

Benefits: Reduced human error, more efficient operations, diminished piracy risk through crewless design.

Risks introduced:

- No human presence to detect/respond to malfunctions.

- Dependency on remote data, satellite navigation, and software supply chains.

- Vulnerability to firmware exploits or communication protocol compromise.

- Legal ambiguity: unclear accountability for cyberattacks or failures.

Autonomy may remove some risks but simultaneously introduces new vulnerabilities — particularly around cybersecurity, decision-making resilience under uncertainty, and liability in degraded or contested environments.

The Expanding Threat Surface

As digitization deepens, entry points for adversaries proliferate:

- Cloud-based shipping management systems.

- Third-party logistics contractors with weaker security hygiene.

- ICS/SCADA in port cranes and ballast systems.

- Crew devices connecting to unsecured or personal networks.

- Customs APIs or supply-chain partners introducing malware.

- Legacy software with decades-old vulnerabilities.

The supply chain itself has become a vector: compromise at one node (e.g., customs API) can cascade across vessels, ports, and global providers.

Legal and Governance Gaps

Technology is outpacing the law. While IMO has issued guidance (e.g., MSC-FAL.1/Circ . 3 on cyber risk management), governance remains incomplete. Key gaps include:

- Cross-border jurisdiction for cyber incidents.

- Liability frameworks for AI-driven maritime decision-making.

- Data governance and privacy at sea.

- Lack of minimum industry-wide cybersecurity standards.

- Insurance regimes are struggling to cover cyber-physical disruption.

Without clear legal scaffolding, both states and corporations face uncertainty — unable to fairly allocate responsibility or ensure compensation after major digital events.

The Human Element Remains Central

Amidst digital transformation, people remain the decisive variable:

- Crew and port staff must evolve beyond safety training into cyber awareness.

- Shore-based logisticians need hybrid fluency in maritime operations and digital risk.

- Executives and boards must treat cyber resilience as a strategic imperative, not an IT function.

- Insider threats — whether deliberate or through negligence — continue to trigger significant breaches.

Technology expands potential, but also complexity. Without trained, empowered humans, even the most advanced systems quickly become liabilities.

These technological advances reinforce the Sea of Risk patterns: tightly coupled systems, cyber-physical fusion, lack of redundancy, and strategic blindness. Automation promises efficiency but reduces resilience if not matched with robust governance. Digitalization brings visibility but also fragility when links break. Human factors — too often marginalized in “next-gen” strategies — remain indispensable to security outcomes.

This means future maritime resilience depends not just on adopting technology, but on adopting interdimensional and transdisciplinary frameworks capable of governing its risks.

The Strategic Gaps

The maritime security system has no shortage of frameworks, conventions, and regulations. ISPS governs the ship–port interface, SOLAS anchors vessel safety, SUA criminalizes unlawful acts, and the IMO issues cyber guidelines. States extend these with national acts, while corporates add compliance regimes shaped by insurers and industry standards.

But when placed against the realities of today’s Sea of Risk — fragile systems of systems, cyber‑physical fusion, and multidimensional threats — these instruments reveal profound limitations. They work in their silos, but rarely in concert; they address yesterday’s shocks more than tomorrow’s horizons.

Siloed by Design: Each framework targets one slice of the puzzle — ports, vessels, unlawful acts, cyber hygiene — but few connect across dimensions (surface ↔ seabed ↔ cyber ↔ space) or across disciplines (law ↔ engineering ↔ environment ↔ economics). Integration remains ad hoc rather than systemic.

Reactive, not Anticipatory: Most frameworks emerged in the wake of singular crises (e.g., 9/11 → ISPS, NotPetya → IMO cyber guidance). This reactive posture struggles with emerging, trans dimensional risks like autonomous vessel failures, hybrid warfare campaigns, or cascading supply chain crises accelerated by digital dependencies.

Jurisdictional Fragmentation: Global standards are extended unevenly through domestic acts, producing overlapping but inconsistent compliance burdens. For corporates operating across multiple jurisdictions, this compliance fragmentation creates friction without closing strategic gaps — forcing duplication of effort rather than shared resilience.

Cyber-Physical Blind Spots: Traditional standards privilege the physical domain (ports, ships, cargo) while neglecting cyber dependencies and hybrid fusion (cyber-induced collisions, AIS spoofing, ransomware-crippled cranes, or sabotage of seabed cables). As operations go digital, these blind spots grow into systemic fault lines.

Weak Integration of Human & Organizational Factors: While frameworks mandate security officers, audits, and basic training, they emphasize compliance over culture. Insider threats, a lack of cyber hygiene, and leadership blind spots remain under-addressed — leaving the human element as both the weakest and most neglected link.

The analysis points to one clear conclusion: the existing corpus of maritime security approaches, standards, and frameworks is necessary but insufficient. They provide critical scaffolding but remain:

- Fragmented across jurisdictions

- Reactive to past events rather than anticipatory of future ones

- Sectoral instead of systemic

- Compliance-driven instead of resilience-driven

These gaps leave maritime governance and industry alike ill-prepared for the realities of the Sea of Risk, where threats ripple across dimensions (surface, seabed, cyber, space), involve disciplines (law, tech, economics, environment), and demand trans dimensional, transdisciplinary responses.

STRATOS: A Strategic Framework for the Sea of Risk

The failures of existing frameworks are not due to the absence of regulation or expertise, but due to their fragmentation, reactivity, and siloed nature. What maritime security requires is an architecture that thinks systemically, operates jointly, and adapts dynamically.

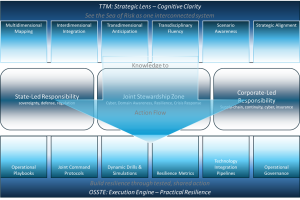

STRATOS (Strategic Thinking and Resilience Across Tactics, Outcomes, and Systems) is proposed as that architecture. It’s the integrative architecture that bridges cognitive clarity (big-picture, strategic thinking across dimensions/disciplines), operational structure (actionable mechanisms and processes for states, corporates, and joint areas), and bridging mechanism (connecting theory/policy to practice, i.e., from “Sea of Risk” analysis to “boots-on-deck” execution). STRATOS is:

- A strategic framework designed to meet the complexity of the Sea of Risk by aligning multidimensional environments with transdisciplinary expertise.

- A provider of cognitive clarity through TTM (Trans dimensional Thinking Model) — ensuring policymakers, corporates, and operators see across dimensions (surface, seabed, cyber, space) and disciplines (law, engineering, environment, economics).

- An operational structure, delivered through OSSTE (Operational Systems for Security, Tactics, and Execution) — translating strategic insights into practicable actions: drills, technologies, protocols, governance arrangements.

- A bridge mechanism that connects high-level strategy with “boots-on-deck” execution, ensuring that resilience is not an abstract concept but a lived practice at sea and in ports.

STRATOS reframes maritime security not as a sectoral checklist, but as a living, systemic ecosystem — integrating state and corporate responsibilities, multidimensional threats, and transdisciplinary expertise into one coherent fabric of resilience.

STRATOS (Strategic Thinking and Resilience Across Tactics, Outcomes, and Systems) is designed as a dual-layer framework:

- TTM – The Trans dimensional Thinking Model (Cognitive Clarity)

- OSSTE – Operational Systems for Security, Tactics, and Execution (Practical Resilience)

Together, they ensure maritime stakeholders can anticipate, integrate, and act across the Sea of Risk.

TTM – Trans dimensional Thinking Model (Cognitive Clarity)

TTM provides the mental architecture to deal with maritime complexity by expanding awareness across dimensions and disciplines, moving beyond silos.

Core Components of TTM:

- Multidimensional Mapping: Ensures threats across physical domains (surface, subsea, seabed, cyber, space) are viewed as interconnected, not isolated.

- Interdimensional Integration: Forces decision-makers to consider linkages (e.g., cyber failure causing surface collisions; seabed cable sabotage impacting economics and geopolitics).

- Trans dimensional Anticipation: Prepares actors to manage hybrid, cross-domain threats that blur boundaries (e.g., state-sponsored cyber-physical disruption, gray-zone coercion).

- Transdisciplinary Fluency: Equips leaders to work across law, cyber, environment, economics, naval defense, and sociology — weaving together knowledge systems into actionable insight.

An Example: A port authority adopting TTM would not only comply with ISPS inspections (surface) but model how a ransomware attack (cyber) could paralyze logistics (economics), then ripple to seabed cable dependencies (infrastructure). These forces integrated contingency design, not single-domain fixes.

OSSTE – Operational Systems for Security, Tactics, and Execution (Practical Resilience)

OSSTE translates cognitive clarity into structured, executable resilience systems for states, corporates, and joint domains. Core Functions of OSSTE:

- Operational Playbooks: Scenario-based guides linking strategy to field-level response (hijacking, ransomware, chokepoint disruption, climate disaster).

- Joint Command Protocols: Mechanisms for state–corporate crisis fusion — enabling navies, regulators, corporations, and insurers to respond in real-time.

- Dynamic Drills & Simulations: Multi-domain rehearsals (cyber + physical + legal/crisis communications) to test integrated responses.

- Resilience Metrics: Move assessment beyond compliance into stress-testing interconnectivity (e.g., does a cyber drill inform physical port redundancy plans?).

- Technology Integration Pipelines: Cross-sector adoption of trusted tools: AI anomaly detection for vessel movement, blockchain for cargo manifests, cyber hardening standards for port ICS.

An Example: A corporate shipping line integrates OSSTE by embedding cyber drills into crew training, linking them with real naval incident response plans, and measuring recovery time not just for ship safety but for financial, legal, and reputational continuity.

STRATOS as a Bridge

Most frameworks today stop at either high-level strategy (policy rhetoric, conventions) or low-level execution (port inspections, corporate compliance). STRATOS explicitly bridges the two:

- TTM provides the “cognitive map,” ensuring decision-makers see the whole Sea of Risk.

- OSSTE provides the “action engine,” ensuring resilience is actionable, measurable, and tested at sea, at ports, and in supply chain networks.

This bridge reframes maritime security not as reactive compliance but as proactive resilience — embedding anticipation, integration, and systemic fluency into everyday maritime operations.

Conclusions

The maritime domain is no longer defined solely by coastlines, ports, or naval strength. It has become a fragile, tightly coupled system of systems that spans surface waters, seabeds, satellites, cyber networks, supply chains, and human communities. In this Sea of Risk, disruptions cascade rapidly: digital breaches trigger physical crises, localized accidents ripple globally, and siloed responses collapse under hybrid threats.

STRATOS (Strategic Thinking and Resilience Across Tactics, Outcomes, and Systems) is proposed as the potential integrative solution. By combining the Trans dimensional Thinking Model (TTM) for cognitive clarity with the Operational Systems for Security, Tactics, and Execution (OSSTE) for practical resilience, STRATOS bridges high-level strategy and “boots-on-deck” action. It equips states, corporates, and joint actors to see risks across dimensions, align expertise across disciplines, and respond collaboratively through systemic, rehearsed resilience.

References

Akpan, F., Bendiab, G., Shiaeles, S., Karamperidis, S., & Michaloliakos, M. (2022). Cybersecurity Challenges in the Maritime Sector. Network, 2(1), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.3390/network2010009

Alcaide, J. I., & Llave, R. G. (2020). Critical infrastructures, cybersecurity, and the maritime sector. Transportation Research Procedia, 45, 547–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2020.03.058

Ammar, M., & Khan, I. A. (2024). Cyber Attacks on Maritime Assets and their Impacts on Health and Safety Aboard: A Holistic View (No. arXiv:2407.08406). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.08406

Andringa, P., Bhandari, A., & Murray, C. (2025). Visual analysis: GPS interference raises the risk of accidents in the Strait of Hormuz. Financial Times.

Australia Department of Home Affairs. (2022, April 6). Australian Government Civil Maritime Security Strategy. Australian Government. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au

Azzab, M., Hahboub, H., Chehri, A., Jakimi, A., & Saadane, R. (2024). Smart Port: An Upshot of the Maritime Sector’s Digital Transformation. 2024 IEEE World Forum on Public Safety Technology (WFPST), 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1109/WFPST58552.2024.10973158

Bateman, S. (2016). Maritime security governance in the Indian Ocean region. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 12(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2016.1138709

Bichou, K., Szyliowicz, J. Z., & Zamparini, L. (2014). Maritime Transport Security: Issues, Challenges and National Policies. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/usd/maritime-transport-security-9781781954966.html

Brasileiro da cibersegurança. (2020). National Defense White Paper – LBDN (2012/2016/2020). https://ciberseguranca.igarape.org.br/en/national-defense-white-paper-lbdn-2012-2016-2020/

Brazil Presidency. (n.d.). National Maritime Policy (PMN): D12481. Retrieved September 7, 2025, from https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2023-2026/2025/Decreto/D12481.htm

Bronk, C., & deWitte, P. (2022). Maritime Cybersecurity: Meeting Threats to Globalization’s Great Conveyor. In M. Lehto & P. Neittaanmäki (Eds.), Cyber Security: Critical Infrastructure Protection (pp. 241–254). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91293-2_10

Burgess, M. (2017, March 27). To protect Putin, Russia is spoofing GPS signals on a massive scale. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/russia-gps-spoofing/

Canada, T. (n.d.). TP 15627 – Canada’s Maritime Security Strategic Framework. AMSM; AMSM. Retrieved September 7, 2025, from https://tc.canada.ca/en/marine-transportation/publications/tp-15627-canada-s-maritime-security-strategic-framework

CARICOM IMPACS. (2024, May 24). Securing the Blue Economy for Present & Future Prosperity. https://www.caricomimpacs.org/articles/caribbean-maritime-security-strategy-and-implementation-plan-securing-the-blue-economy-for-present-and-future-prosperity

Chiriac, O. (2022, November 28). The 2022 Maritime Doctrine of the Russian Federation: Mobilization, Maritime Law, and Socio-Economic Warfare | Center for International Maritime Security. https://cimsec.org/the-2022-maritime-doctrine-of-the-russian-federation-mobilization-maritime-law-and-socio-economic-warfare/

Council of the EU. (2023, October 23). Maritime security: Council approves revised EU strategy and action plan. Consilium. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/10/24/maritime-security-council-approves-revised-eu-strategy-and-action-plan/

Crickard, F. (1995). Canada’s ocean and maritime security: a strategic forecast. Marine Policy, 19(4), 335–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/0308-597X(95)00012-U

Das, H. (2018). India’s maritime security governance challenges: A decade after “26/11.” Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India, 14(2), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/09733159.2019.1565442

DHS. (2005). Maritime Transportation System Security Recommendations. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/HSPD_MTSSPlan_0.pdf

Diaz, R., Smith, K., Bertagna, S., & Bucci, V. (2023). Digital Transformation, Applications, and Vulnerabilities in Maritime and Shipbuilding Ecosystems. Procedia Computer Science, 217, 1396–1405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.12.338

Dyner, A. M. (2022, August 2). Russia Adopts More Confrontational Maritime Doctrine. https://pism.pl/publications/russia-adopts-more-confrontational-maritime-doctrine

Germond, B. (2015). The geopolitical dimension of maritime security. Marine Policy, 54, 137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2014.12.013

Gopal, P. (2020). Maritime domain awareness and India’s maritime security strategy: Role, effectiveness, and the way ahead. Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India, 16(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/09733159.2020.1840060

Grispos, G., & Mahoney, W. R. (2022). Cyber Pirates Ahoy! An Analysis of Cybersecurity Challenges in the Shipping Industry (No. arXiv:2208.03607). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2208.03607

Gu, B., & Liu, J. (2025). A systematic review of resilience in maritime transport. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 28(3), 257–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2023.2165051

Indian Navy Directorate of Strategy, Concepts and Transformation, I. (2015). Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy: Vol. Volume 1 of the Naval Strategic Publication. Indian Navy.

Khurana, G. S. (2017). India’s Maritime Strategy: Context and Subtext. Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India, 13(1), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09733159.2017.1309747

LaRocco, L. A. (2024, April 17). Biden admin, US ports prep for cyberattacks as nationwide infrastructure is targeted. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2024/04/17/biden-admin-ports-prep-for-cyberattacks-as-us-infrastructure-targeted.html

Li, M., Zhou, J., Chattopadhyay, S., & Goh, M. (2024). Maritime Cybersecurity: A Comprehensive Review (No. arXiv:2409.11417). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.11417

LLo. (2019). Shen attack: The economic impact of a cyber attack on Asia-Pacific ports. https://www.lloyds.com/insights/media-centre/press-releases/cyber-attack-on-apac-ports-could-cost-110bn

Marinha Do Brasil. (n.d.). Plano Estratégico da Marinha 2040 (PEM 2040). Retrieved September 7, 2025, from https://www.marinha.mil.br/publicacoes/pem2040?__cf_chl_f_tk=.Hwcmoy6BwoxqzqfiC_TqQoVeWipQsKpLBgTEgPeYc0-1757260166-1.0.1.1-a5QWRQGByQjPYZJhwNrJHEciqnazVEb_4G_O5EFniHA

Maritime security. (n.d.). Consilium. Retrieved September 7, 2025, from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/maritime-security/

Muraviev, A. D. (223 C.E.). Battle Reading the Russian Pacific Fleet 2023-2030. Sea Power Centre, Australia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375186660_SEA_POWER_PAPER_Battle_Reading_the_Russian_Pacific_Fleet_2023-2030

NATO. (2021, November 30). NATO Review—Hybrid Warfare – New Threats, Complexity, and ‘Trust’ as the Antidote. NATO Review. https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2021/11/30/hybrid-warfare-new-threats-complexity-and-trust-as-the-antidote/index.html

Otto, L., & Menzel, A. (Eds.). (2024). Global Challenges in Maritime Security: Sustainability and the Sea. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-59903-3

Pratson, L. F. (2023). Assessing impacts to maritime shipping from marine chokepoint closures. Communications in Transportation Research, 3, 100083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commtr.2022.100083

Ratiu, A. (2021, October 4). A system of systems: Cooperation on maritime cybersecurity. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/cooperation-on-maritime-cybersecurity-a-system-of-systems/

Rear Admiral Michael McDevitt. (n.d.). Becoming a Great “Maritime Power”: A Chinese Dream. Retrieved September 7, 2025, from https://www.cna.org/analyses/2016/china-becoming-a-maritime-power

Schöttli, J. (2019). “Security and growth for all in the Indian Ocean” – maritime governance and India’s foreign policy. India Review, 18(5), 568–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/14736489.2019.1703366

Shipping data: UNCTAD releases new seaborne trade statistics | UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2025, April 23). https://unctad.org/news/shipping-data-unctad-releases-new-seaborne-trade-statistics

Stritzel, H. (2014). Security in Translation. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137307576

Thai, V. V. (2009). Effective maritime security: Conceptual model and empirical evidence. Maritime Policy & Management, 36(2), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088830902868115

Thakur, S. P. (2024, April 19). Hidden in Plain Sight: The Strategic Significance and Vulnerabilities of Maritime Chokepoints. Bloomsbury Intelligence & Security Institute (BISI). https://bisi.org.uk/reports/hidden-in-plain-sight-the-strategic-significance-and-vulnerabilities-of-maritime-chokepoints

The Information Office of the State Council. (2015, May 27). China’s Military Strategy (full text). https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2015/05/27/content_281475115610833.htm

Till, G. (2023, March 9). IP23022 | Russian Maritime Strategy and the Pacific—RSIS. https://rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/idss/ip23022-russian-maritime-strategy-and-the-pacific/

Triebert, C., Migliozzi, B., Cardia, A., Xiao, M., & Botti, D. (2023, May 31). Fake Signals and American Insurance: How a Dark Fleet Moves Russian Oil. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/05/30/world/asia/russia-oil-ships-sanctions.html

UNTAD. (2024, October 22). Vulnerability of supply chains exposed as global maritime chokepoints come under pressure. https://unctad.org/news/vulnerability-supply-chains-exposed-global-maritime-chokepoints-come-under-pressure

Voyer, M., Schofield, C., Azmi, K., Warner, R., McIlgorm, A., & Quirk, G. (2018). Maritime security and the Blue Economy: Intersections and interdependencies in the Indian Ocean. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 14(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2018.1418155

World Maritime University. (2019). Transport 2040: Autonomous ships: A new paradigm for Norwegian shipping – Technology and transformation. Reports. http://dx.doi.org/10.21677/itf.20190715

World Ports. (2025, May 15). Container ship grounded near Jeddah due to GPS spoofing, says Dryad. Container Ship Grounded near Jeddah Due to GPS Spoofing, Says Dryad. https://www.worldports.org/container-ship-grounded-near-jeddah-due-to-gps-spoofing-says-dryad/

郑成琼. (2025, May 13). Abstract of white paper on China’s national security in the new era. http://english.scio.gov.cn/whitepapers/2025-05/13/content_117871660.html

Endnotes

[3] These are based on web searches and not scientific

[4] Much of this information is synthesized based on the author’s hypothesis of maritime systems split into mainland and transportation from various sources, including CARICOM IMPACS (024;), DHS (2005), Otto & Menze ( 2024), Rati ( 2021), and Stritzel (2014)

[5] One can go to the respective countries’ maritime website and get this with a lot more information as well

[6] Although China does not issue a separate maritime security strategy, key documents such as the 2025 National Security White Paper elevate maritime rights as strategic priorities ((郑成琼, 2025)), the 2015 Military Strategy White Paper commits to transitioning from a land‑centric to a maritime‑focused security posture ((The Information Office of the State Council, 2015)), and earlier government publications clarify the PLA’s role in joint maritime governance and protection (see this for analysis as the bookmarked publication was no longer locatable online, (Rear Admiral Michael McDevitt, n.d.))

[7] The EU has loads of documents, blog articles, and discussions available on its various forums and websites. Of the many, we found a few very useful and list them here. The EU’s revised Maritime Security Strategy (Council of the EU, 2023) sets out six strategic objectives—spanning naval activity, partnerships, maritime domain awareness, capability enhancement, risk management, and training—to boost its maritime security posture. These strategic priorities have been operationalized through initiatives like MARSEC EU 25, which targets threats such as illegal fishing and infrastructure sabotage, as well as through naval missions like Operation Atalanta and Operation Aspides in high-risk regions. Underpinning all of this are information-sharing platforms like CISE and MARSUR, which enhance situational awareness and secure cooperation across EU actors (See also, https://www.iss.europa.eu/publications/briefs/eu-maritime-security-provider)

[8] While there are a lot of news articles available, there is not much from the government websites. We found these references useful (Bateman, 2016; Das, 2018; Gopal, 2020; Khurana, 2017; Schöttli, 2019; Voyer et al., 2018)

[9] There are several resources available on the web. We found these useful (Chiriac, 2022; Dyner, 2022; Muraviev, 223 C.E.; Till, 2025, and this bookmark was no longer available from Canada, https://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/on-the-road-to-strategic-depth-in-the-black-sea-region

[10] The UK’s National Strategy for Maritime Security (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-maritime-security-strategy) provides a cross-governmental action plan with five strategic objectives focused on home protection, threat response, economic resilience, values, and sustainable seas. This is operationalized through doctrinal guidance like Joint Doctrine Publication 0‑10 (UK Maritime Power) (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-maritime-power-jdp-0-10), centralized coordination via the Joint Maritime Security Centre (https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/joint-maritime-security-centre), and future-focused naval engagement outlined in the 2025 Strategic Defence Review, which including protecting undersea infrastructure through multi-domain surveillance and autonomy (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-strategic-defence-review-2025-making-britain-safer-secure-at-home-strong-abroad/the-strategic-defence-review-2025-making-britain-safer-secure-at-home-strong-abroad).

[11] US maritime security combines statutory mandates like the MTSA (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maritime_Transportation_Security_Act_of_2002) with comprehensive strategies and interagency plans (https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/homeland/maritime-security.html), operational risk tools such as MSRAM and MAGNET (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maritime_Security_Risk_Analysis_Model, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maritime_Awareness_Global_Network), and evolving cybersecurity directives (https://www.dhs.gov/national-plan-achieve-maritime-domain-awareness). Strategic maritime doctrine is embodied in CS21 (https://www.dhs.gov/archive/news/2024/02/21/fact-sheet-dhs-moves-improve-supply-chain-resilience-and-cybersecurity-within-our), while regional security partnerships and advanced intelligence integration are reflected in Operation Blue Pacific (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Cooperative_Strategy_for_21st_Century_Seapower) and NMIO’s strategy (https://nmio.ise.gov/About/Strategy), respectively.

[12] These are based on the author’s review of multiple news articles on corporate and government websites. Ones that were very influential in our analysis are, UK National maritime security strategy available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-maritime-security-strategy, the 2005 White House document available at: https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/homeland/maritime-security.html, the WEF Global Maritime Risk Report available at: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2025/, and the IMO Maritime Cyber risk available at: https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/security/pages/cyber-security.aspx

[15] Available at https://imo-2021.com/, https://www.shipuniverse.com/2025-maritime-cybersecurity-regulations-a-simplified-breakdown/

[16] See the news article, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2025/03/20/ntsb-bridge-safety-dali-recommendation/ and the NTSB report, https://www.ntsb.gov/news/press-releases/Pages/nr20250320.aspx

[17] These are some available news articles: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/from-russias-shadow-fleet-to-chinas-maritime-claims-the-freedom-of-the-seas-is-under-threat/, https://www.iss.europa.eu/publications/briefs/four-swans-black-sea, and this page was not available when it was sent to the editor: https://understandingwar.org/research/russia/ukrainian-strikes-have-changed-russian-naval-operations-black-sea/

[18] Available at: https://www.controleng.com/throwback-attack-how-notpetya-accidentally-took-down-global-shipping-giant-maersk/, https://www.cybereason.com/blog/notpetya-costs-companies-1.2-billion-in-revenue, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/08/16/maersk-says-notpetya-cyberattack-could-cost-300-million.html. About the Petya malware family: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petya_(malware_family)

[19] These are based on our review of the literature, news articles, and other information already made available in the previous sections