Chapter 12: Fact Checking

Walter Butler; Aloha Sargent; and Kelsey Smith

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify effective strategies for fact-checking sources

- Investigate a source of information to determine reliability

- Find better coverage for a source of information

- Trace claims, quotes, and media to their original context

As an introduction, please watch the following video [3:13], which discusses the results of a very interesting study of Stanford students, historians, and professional fact-checkers (Wineburg and McGrew). Which group do you think did the best job of identifying reliable sources?

Note: Turn on closed captions with the “CC” button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

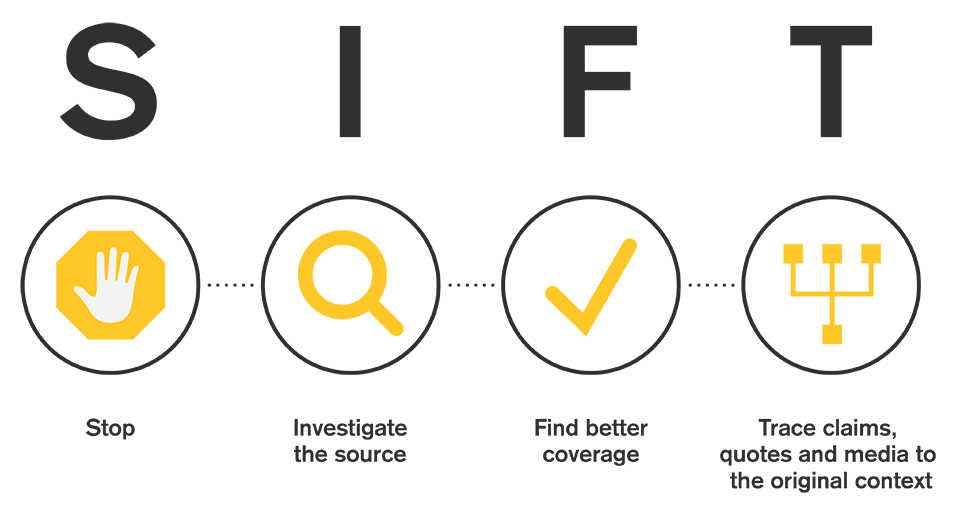

Stop

![]()

When you initially encounter a source of information and start to read it—stop. Ask yourself whether you know and trust the author, publisher, publication, or website. If you don’t, use the other fact-checking moves that follow, to get a better sense of what you’re looking at. In other words, don’t read, share, or use the source in your research until you know what it is, and you can verify it is reliable.

This is a particularly important step, considering what we know about the attention economy—social media, news organizations, and other digital platforms purposely promote sensational, divisive, and outrage-inducing content that emotionally hijacks our attention in order to keep us “engaged” with their sites (clicking, liking, commenting, sharing). Stop and check your emotions before engaging!

Investigate the Source

![]()

You don’t have to do a three-hour investigation into a source before you engage with it. But if you’re reading a piece on economics, and the author is a Nobel prize-winning economist, that would be useful information. Likewise, if you’re watching a video on the many benefits of milk consumption, you would want to be aware if the video was produced by the dairy industry. This doesn’t mean the Nobel economist will always be right and that the dairy industry can’t ever be trusted. But knowing the expertise and agenda of the person who created the source is crucial to your interpretation of the information provided.

When investigating a source, fact-checkers read “laterally” across many websites, rather than digging deep (reading “vertically”) into the one source they are evaluating. That is, they don’t spend much time on the source itself, but instead they quickly get off the page and see what others have said about the source. They open up many tabs in their browser, piecing together different bits of information from across the web to get a better picture of the source they’re investigating.

Please watch the following short video [2:44] for a demonstration of this strategy. Pay particular attention to how Wikipedia can be used to quickly get useful information about publications, organizations, and authors.

Note: Turn on closed captions with the “CC” button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Find Better Coverage

![]()

What if the source you find is low-quality, or you can’t determine if it is reliable or not? Perhaps you don’t really care about the source—you care about the claim that source is making. You want to know if it is true or false. You want to know if it represents a consensus viewpoint, or if it is the subject of much disagreement. A common example of this is a meme you might encounter on social media. The random person or group who posted the meme may be less important than the quote or claim the meme makes.

Your best strategy in this case might actually be to find a better source altogether, to look for other coverage that includes trusted reporting or analysis on that same claim. Rather than relying on the source that you initially found, you can trade up for a higher quality source.

The point is that you’re not wedded to using that initial source. We have the internet! You can go out and find a better source, and invest your time there. Please watch this video [4:10] that demonstrates this strategy and notes how fact-checkers build a library of trusted sources they can rely on to provide better coverage.

Note: Turn on closed captions with the “CC” button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Trace Claims, Quotes, and Media to the Original Context

![]()

Much of what we find on the internet has been stripped of context. Maybe there’s a video of a fight between two people with Person A as the aggressor. But what happened before that? What was clipped out of the video and what stayed in? Maybe there’s a picture that seems real but the caption could be misleading. Maybe a claim is made about a new medical treatment based on a research finding—but you’re not certain if the cited research paper actually said that. The people who re-report these stories either get things wrong by mistake, or, in some cases, they are intentionally misleading us.

In these cases you will want to trace the claim, quote, or media back to the source, so you can see it in its original context and get a sense of whether the version you saw was accurately presented. Please watch the following video [1:33] that discusses re-reporting vs. original reporting and demonstrates a quick tip: going “upstream” to find the original reporting source.

Note: Turn on closed captions with the “CC” button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

“To tell students not to use Wikipedia is to deprive them of one of the most useful tools on the Internet. Instead of teaching them to avoid it, we should be teaching students how to use Wikipedia wisely” (“How to Use Wikipedia Wisely”).

Misconceptions & Benefits

Wikipedia—the world’s largest reference website—is broadly misunderstood. Because it is written by thousands of anonymous volunteers around the world, Wikipedia generates uncertainty or skepticism in many. If just anyone can change Wikipedia, won’t there be inaccuracies? Won’t people potentially abuse that power?

The open, collaborative approach of Wikipedia means that it is susceptible to vandalism, unverified information, or subtle viewpoint promotion. However, that same open approach also increases the chances that factual errors and misleading statements will be quickly corrected, and that articles will be consistently improved and updated. Indeed, an often-cited 2005 study (Giles), as well as a follow-up study in 2012 (Casebourne et al.), found no significant differences in accuracy between Wikipedia and Encyclopaedia Britannica articles.

![]()

Additionally, the Wikipedia community has strict rules about providing citations or references for facts and claims, and authors must adopt a neutral point of view. Because of this, Wikipedia articles are often the best available introduction to a subject. If you are researching a complex question, starting with the resources and summaries provided by Wikipedia can give you a substantial running start on an issue. For more information about this, see the section on Background Reading. The requirement for Wikipedia authors to cite their sources has another beneficial effect. If you can find a claim expressed in a Wikipedia article, you can almost always follow the footnotes to reliable sources for further research and evidence.

Areas for Caution

Not all Wikipedia articles are useful. Some articles are incomplete or contain “citation needed” warnings. You may find very short “stub” articles that are awaiting either further expansion, or deletion. You should avoid using these types of articles for your research.

Another known concern is systemic bias in Wikipedia, including gender and racial bias. For example, of the over 130,000 active editors of Wikipedia, only 8.5% to 16% are female; of the over 1.5 million biographies on Wikipedia, only 18% are about women (Kantor). Wikipedia has launched numerous initiatives to encourage more women to become editors and to improve their coverage of women; even so, the gender gap persists. With Wikipedia as well as other, more traditional forms of publishing, we must be aware of who creates the information we consume, and understand how that impacts our knowledge about research topics and the world around us. For more on bias, see the page on Information Sources: Bias.

Using Wikipedia Wisely

With an awareness of these benefits and concerns, you can more effectively use Wikipedia for fact-checking and to find background information on a topic. Please watch the following video [2:41] that addresses some of the common misconceptions about Wikipedia and demonstrates how you can use this tool wisely, as professional fact-checkers often do.

Note: Turn on closed captions with the “CC” button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Find Trusted Coverage

Often, claims or stories will come to you in the form of images and memes. How do you know if images have been digitally altered (Photoshopped) or if they are being shared out of context (misrepresented)?

If you want to find trusted coverage of the issue, claim, or photo, you have two options:

- You can search the relevant text from the image

- You can use “reverse image search”

Reverse Image Search Using Google

On your Computer

Using Chrome as your browser, right-click the image and select “Search Google for image.” Note: On a Mac, use Control-click. On a Chromebook, use Alt-click.

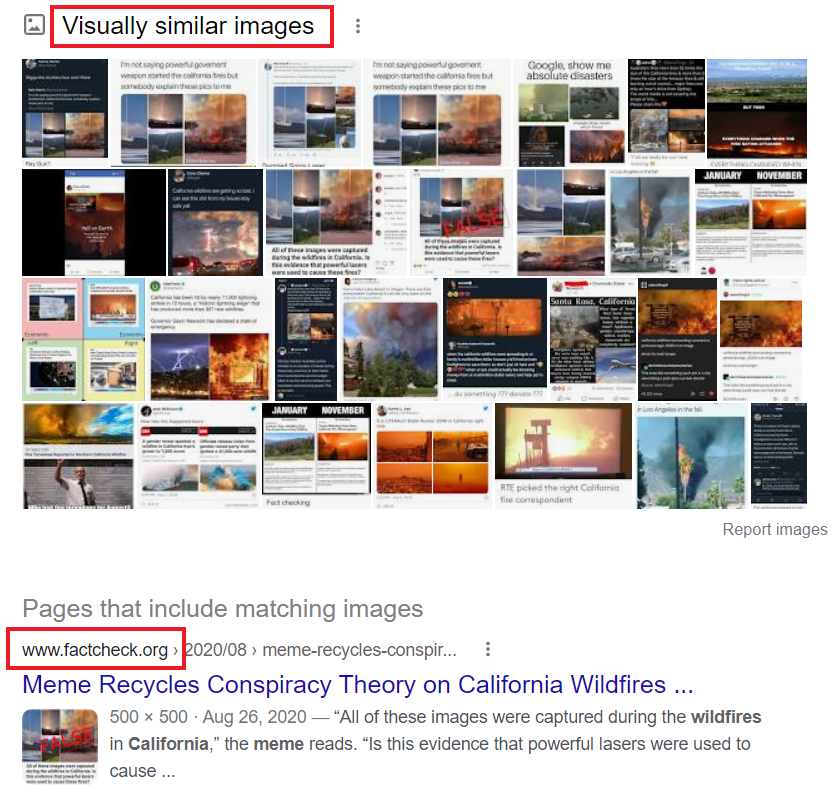

In the example below, we can do a reverse image search on this meme that suggests space lasers were responsible for the California wildfires.

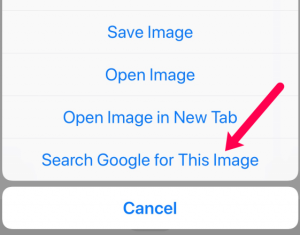

On your Phone

Using Chrome (app), touch and hold the image, then select “Search Google for This Image” Note: You may first have to click a menu option to “Open in Chrome”

The Results

You will get a list of any other websites where the image has been used, including previous fact-checks of the image, and perhaps even a link to the real version of the photo.

In our example, we see that this meme has appeared in many other places, and that it has already been shown to be false by a reputable fact-checking organization.

The results of this fact-checking led to some of the actual images, in context. In the screenshot below from the Twitter account for SpaceX, we see that the first image from the meme was actually an image of a SpaceX rocket launch, not a laser beam hitting California.

Licenses and Attributions:

Original content: CC BY Attribution:

Introduction to College Research Fact Checking. Access for free at: https://pressbooks.pub/introtocollegeresearch

Butler, D., Sargent, A., Smith, K. Fact Checking. In Introduction to College Research.

Modifications: Figures numbered.

Sources

“Online Verification Skills – Video 1: Introductory Video.” YouTube, uploaded by CTRL-F, 29 June 2018.

Wineburg, Sam, and Sarah McGrew. “Lateral Reading: Reading Less and Learning More When Evaluating Digital Information.” Stanford History Education Group Working Paper No. 2017-A1, 6 Oct. 2017, dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3048994.

“Online Verification Skills – Video 2: Investigate the Source.” YouTube, uploaded by CTRL-F, 29 June 2018.

“Online Verification Skills – Video 3: Find the Original Source.” YouTube, uploaded by CTRL-F, 25 May 2018.

“Online Verification Skills – Video 4: Look for Trusted Work.” YouTube, uploaded by CTRL-F, 25 May 2018.

SIFT text adapted from “Check, Please! Starter Course,” licensed under CC BY 4.0

SIFT text and graphics adapted from “SIFT (The Four Moves)” by Mike Caulfield, licensed under CC BY 4.0

Casebourne, Imogen, et al. “Assessing the Accuracy and Quality of Wikipedia Entries Compared to Popular Online Encyclopaedias: A Comparative Preliminary Study Across Disciplines in English, Spanish and Arabic.” Wikimedia, Epic and Univ. of Oxford, 2012. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Giles, Jim. “Internet Encyclopaedias Go Head to Head.” Nature, vol. 438, 2005, pp. 900–901, doi.org/10.1038/438900a.

“How to Use Wikipedia Wisely.” YouTube, uploaded by Stanford History Education Group, 23 Jan. 2020.

Image: “Run” by Alex Podolsky, adapted by Aloha Sargent, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Kantor, Jessica. “Wikipedia Still Hasn’t Fixed Its Colossal Gender Gap.” Fast Company, 13 Nov. 2019.

Misconceptions and Benefits section adapted from “Web Literacy for Student Fact-Checkers” by Mike Caulfield, licensed under CC BY 4.0 and “Teaching with Wikipedia: A High Impact Open Educational Practice” by TJ Bliss, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Find Trusted Coverage section adapted from “Check, Please! Starter Course,” licensed under CC BY 4.0

Reverse Image Search section adapted from “Library 10” by Cabrillo College Library, licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image: “Rainbow Frequency” by Ricardo Gomez Angel is in the Public Domain, CC0

Text adapted from “SIFT (The Four Moves)” by Mike Caulfield, licensed under CC BY 4.0