Chapter 2: Motivation, Growth Mindset, and Self-Efficacy

Amy Baldwin; Julie Hovden; Anh Nguyen; and Aivee Ortega

Questions to Consider:

- What are motivation, growth mindset, and self-efficacy and how do they affect my learning?

- What are performance goals versus learning goals?

Motivation

Every New Year, many people make resolutions—or goals—that go unsatisfied: eat healthier; pay better attention in class; lose weight. As much as we know our lives would improve if we actually achieved these goals, people quite often don’t follow through. But what if that didn’t have to be the case? What if every time we made a goal, we actually accomplished it? Each day, our behavior is the result of countless goals—maybe not goals in the way we think of them, like getting that beach body or being the first person to land on Mars. But even with “mundane” goals, like getting food from the grocery store, or showing up to work on time, we are often enacting the same psychological processes involved with achieving loftier dreams. To understand how we can better attain our goals, let’s begin with defining what a goal is and what underlies it, psychologically.

A goal is the cognitive representation of a desired state, or, in other words, our mental idea of how we’d like things to turn out (Fishbach & Ferguson 2007; Kruglanski, 1996). This desired end state of a goal can be clearly defined (e.g., stepping on the surface of Mars), or it can be more abstract and represent a state that is never fully completed (e.g., eating healthy). Underlying all of these goals, though, is motivation, or the psychological driving force that enables action in the pursuit of that goal (Lewin, 1935). Motivation can stem from two places. First, it can come from the benefits associated with the process of pursuing a goal (intrinsic motivation). For example, you might be driven by the desire to have a fulfilling experience while working on your Mars mission. Second, motivation can also come from the benefits associated with achieving a goal (extrinsic motivation), such as the fame and fortune that come with being the first person on Mars (Deci & Ryan, 1985). One easy way to consider intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is through the eyes of a student. Does the student work hard on assignments because the act of learning is pleasing (intrinsic motivation)? Or does the student work hard to get good grades, which will help land a good job (extrinsic motivation)?

Social psychologists recognize that goal pursuit and the motivations that underlie it do not depend solely on an individual’s personality. Rather, they are products of personal characteristics and situational factors. Indeed, cues in a person’s immediate environment (including images, words, sounds, and the presence of other people) can activate, or prime, a goal. This activation can be conscious, such that the person is aware of the environmental cues influencing his/her pursuit of a goal. However, this activation can also occur outside a person’s awareness, and lead to nonconscious goal pursuit. In this case, the person is unaware of why s/he is pursuing a goal and may not even realize that s/he is pursuing it.

Common sense suggests that human motivations originate from some sort of inner need. We all think of ourselves as having various needs that influence our choices and activities. For example, we have a need for food or a need for companionship. This same idea also forms part of some theoretical accounts of motivation, though the theories differ in the needs that they emphasize or recognize.

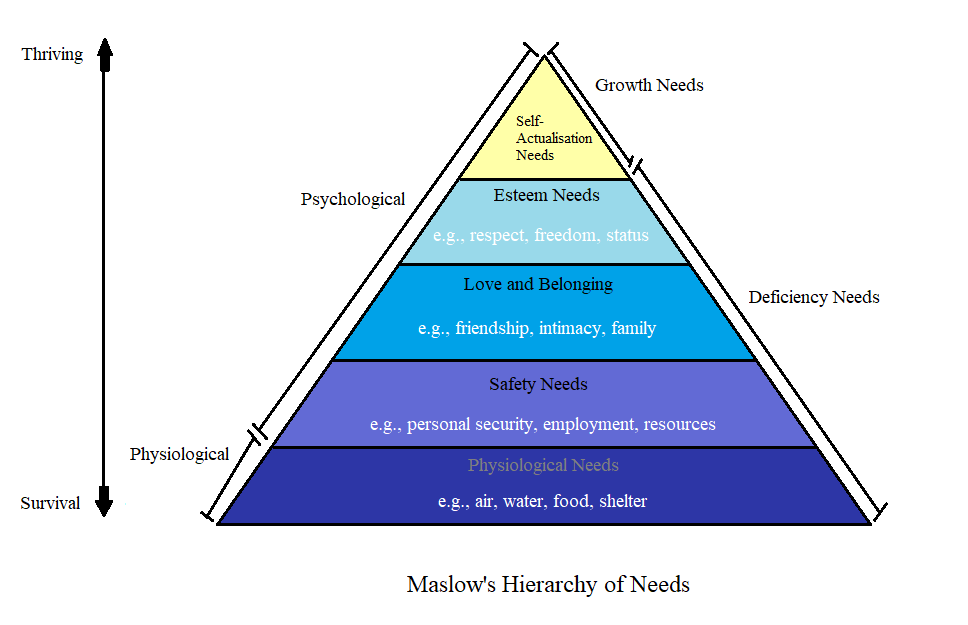

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

One such theory on motivation is that of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. According to Abraham Maslow and his hierarchy of needs, individuals must satisfy physical survival needs before they seek to satisfy needs of belonging, they satisfy belonging needs before esteem needs, and so on. People have both deficit needs and growth needs, and the deficit needs must be satisfied before growth needs can influence behavior (Maslow, 1970). In Maslow’s theory, as in others that use the concept, a need is a relatively lasting condition or feeling that requires relief or satisfaction and that tends to influence action over the long term. Some needs may decrease when satisfied (like hunger), but others may not (like curiosity). Either way, needs differ from the self-efficacy beliefs discussed earlier, which are relatively specific and cognitive, and affect particular tasks and behaviors fairly directly.

Another theory of motivation based on the idea of needs is self-determination theory, proposed by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan (2000). The theory proposes that understanding motivation requires taking into account three basic human needs:

- autonomy—the need to feel free of external constraints on behavior

- competence—the need to feel capable or skilled

- relatedness—the need to feel connected or involved with others

Note that these needs are all psychological, not physical; hunger and sex, for example, are not on the list. They are also about personal growth or development, not about deficits that a person tries to reduce or eliminate. Unlike food (in behaviorism) or safety (in Maslow’s hierarchy), you can never get enough of autonomy, competence, or relatedness. You will seek to enhance these continually throughout life.

The key idea of self-determination theory is that when people feel that these basic needs are reasonably well met, they tend to perceive their actions and choices to be intrinsically motivated or “self-determined”. In that case, they can turn their attention to a variety of activities that they find attractive or important, but that do not relate directly to their basic needs. If one or more basic needs are not met well, however, people will tend to feel coerced by outside pressures or external incentives. They may become preoccupied, in fact, with satisfying whatever need has not been met and thus exclude or avoid activities that might otherwise be interesting, educational, or important. If the people are students, their learning will suffer.

Self-Determination Theory and Intrinsic Motivation

In proposing the importance of needs, then, self-determination theory is asserting the importance of intrinsic motivation. The self-determination version of intrinsic motivation emphasizes a person’s perception of freedom, rather than the presence or absence of “real” constraints on action. Self-determination means a person feels free, even if the person is also operating within certain external constraints. In principle, a student can experience self-determination even if the student must, for example, live within externally imposed rules of appropriate classroom behavior. To achieve a feeling of self-determination, however, the student’s basic needs must be met—needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. To develop intrinsic motivation, students need to find ways to meet these basic needs.

There is an element of the college experience that will improve your ability to meet the expectations and new challenges: Your belief in your abilities to learn, grow, and change. No doubt that you have enrolled in college because you want to do those very things, but it is easy to get discouraged and revert to old ways of thinking about your abilities if you are not mindful of what kinds of thoughts you have about yourself. This section covers the concept of a fixed mindset, or the belief that you are born with certain unchangeable talents, and growth mindset, or the belief that with effort you can improve in any area. Understanding the role that your beliefs play in the eventual outcomes of your learning can help you get through those challenges that you may encounter.

Performance vs. Learning Goals

Much of our ability to learn is governed by our motivations and goals. Sometimes hidden goals or mindsets can impact the learning process. In truth, we all have goals that we might not be fully aware of, or if we are aware of them, we might not understand how they help or restrict our ability to learn. An illustration of this can be seen in a comparison of a student that has performance-based goals with a student that has learning-based goals.

If you are a student with strict performance goals, your primary psychological concern might be to appear intelligent to others. At first, this might not seem to be a bad thing for college, but it can truly limit your ability to move forward in your own learning. Instead, you would tend to play it safe without even realizing it. For example, a student who is strictly performance-goal-oriented will often only say things in a classroom discussion when they think it will make them look knowledgeable to the instructor or their classmates. Likewise, a performance-oriented student might ask a question that they know is beyond the topic being covered (e.g., asking about the economics of Japanese whaling while discussing the book Moby Dick in an American literature course). Rarely will they ask a question in class because they actually do not understand a concept. Instead they will ask questions that make them look intelligent to others or in an effort to “stump the teacher.” When they do finally ask an honest question, it may be because they are more afraid that their lack of understanding will result in a poor performance on an exam rather than simply wanting to learn.

If you are a student who is driven by learning goals, your interactions in classroom discussions are usually quite different. You see the opportunity to share ideas and ask questions as a way to gain knowledge quickly. In a classroom discussion you can ask for clarification immediately if you don’t quite understand what is being discussed. If you are a person guided by learning goals, you are less worried about what others think since you are there to learn and you see that as the most important goal.

Another example where the difference between the two mindsets is clear can be found in assignments and other coursework. If you are a student who is more concerned about performance, you may avoid work that is challenging. You will take the “easy A” route by relying on what you already know. You will not step out of your comfort zone because your psychological goals are based on approval of your performance instead of being motivated by learning.

This is very different from a student with a learning-based psychology. If you are a student who is motivated by learning goals, you may actively seek challenging assignments, and you will put a great deal of effort into using the assignment to expand on what you already know. While getting a good grade is important to you, what is even more important is the learning itself.

If you find that you sometimes lean toward performance-based goals, do not feel discouraged. Many of the best students tend to initially focus on performance until they begin to see the ways it can restrict their learning. The key to switching to learning-based goals is often simply a matter of first recognizing the difference and seeing how making a change can positively impact your own learning.

What follows in this section is a more in-depth look at the difference between performance- and learning- based goals. This is followed by an exercise that will give you the opportunity to identify, analyze, and determine a positive course of action in a situation where you believe you could improve in this area.

Fixed vs. Growth Mindset

The research-based model of these two mindsets and their influence on learning was presented in 1988 by Carol Dweck. In Dweck’s work, she determined that a student’s perception about their own learning accompanied by a broader goal of learning had a significant influence on their ability to overcome challenges and grow in knowledge and ability. This has become known as the Fixed vs. Growth Mindset model. In this model, the performance-goal-oriented student is represented by the fixed mindset, while the learning-goal- oriented student is represented by the growth mindset.

In the following graphic, based on Dr. Dweck’s research, you can see how many of the components associated with learning are impacted by these two mindsets.

The Growth Mindset and Lessons About Failing

Something you may have noticed is that a growth mindset would tend to give a learner grit and persistence. If you had learning as your major goal, you would normally keep trying to attain that goal even if it took you multiple attempts. Not only that, but if you learned a little bit more with each try you would see each attempt as a success, even if you had not achieved complete mastery of whatever it was you were working to learn.

With that in mind, it should come as no surprise that Dweck found that those people who believed their abilities could change through learning (growth vs. a fixed mindset) readily accepted learning challenges and persisted despite early failures.

Improving Your Ability to Learn

As strange as it may seem, research into fixed vs. growth mindset has shown that if you believe you can learn something new, you greatly improve your ability to learn. At first, this may seem like the sort of feel-good advice we often encounter in social media posts or quotes that are intended to inspire or motivate us (e.g., believe in yourself!), but in looking at the differences outlined between a fixed and a growth mindset, you can see how each part of the growth mindset path can increase your probability of success when it comes to learning.

ACTIVITY 2.1

Very few people have a strict fixed or growth mindset all of the time. Often we tend to lean one way or another in certain situations. For example, a person trying to improve their ability in a sport they enjoy may exhibit all of the growth mindset traits and characteristics, but they find themselves blocked in a fixed mindset when they try to learn something in another area like computer programming or arithmetic.

In this exercise, do a little self-analysis and think of some areas where you may find yourself hindered by a fixed mindset. Using the outline presented below, in the far right column, write down how you can change your own behavior for each of the parts of the learning process. What will you do to move from a fixed to a growth mindset? For example, say you were trying to learn to play a musical instrument. In the Challenges row, you might pursue a growth path by trying to play increasingly more difficult songs rather than sticking to the easy ones you have already mastered. In the Criticism row, you might take someone’s comment about a weakness in timing as a motivation for you to practice with a metronome. For Success of Others you could take inspiration from a famous musician that is considered a master and study their techniques.

Whatever it is that you decide you want to use for your analysis, apply each of the Growth characteristics to determine a course of action to improve.

| Parts of the learning process | Growth characteristic | What will you do to adopt a growth mindset? |

|---|---|---|

| Challenges | Embraces challenges | |

| Obstacles | Persists despite setbacks | |

| Effort | Sees effort as a path to success | |

| Criticism | Learns from criticism | |

| Success of Others | Finds learning and inspiration in the success of others |

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is the belief that you are capable of carrying out a specific task or of reaching a specific goal. Note that the belief and the action or goal are specific. In addition to being influenced by their goals, interests, and attributions, students’ motives are affected by specific beliefs about the student’s personal capacities. In self-efficacy theory, the beliefs become a primary, explicit explanation for motivation (Bandura, 1977, 1986, 1997). For example, self-efficacy is a belief that you can write an acceptable term paper or repair an automobile, or make friends with the new student in class. These are relatively specific beliefs and tasks. Self-efficacy is not about whether you believe that you are intelligent in general, whether you always like working with mechanical things, or think that you are generally a likeable person. These more general judgments are better regarded as various mixtures of self-concepts (beliefs about general personal identity) or of self-esteem (evaluations of identity). They are important in their own right, and sometimes influence motivation, but only indirectly (Bong & Skaalvik, 2004).

Self-efficacy beliefs, furthermore, are not the same as “true” or documented skill or ability. They are self-constructed, meaning that they are personally developed perceptions. As with confidence, it is possible to have either too much or too little self-efficacy. The optimum level seems to be either at or slightly above true capacity (Bandura, 1997). As we indicate below, large discrepancies between self-efficacy and ability can create motivational problems for the individual.

Sources of Self-Efficacy Beliefs

Psychologists who study self-efficacy have identified four major sources of self-efficacy beliefs (Pajares & Schunk, 2001, 2002). In order of importance they are (1) prior experiences of mastering tasks, (2) watching others’ mastering tasks, (3) messages or “persuasion” from others, and (4) emotions related to stress and discomfort.

Effects of Self-Efficacy on Students’ Behavior

Self-efficacy may sound like a uniformly desirable quality, but research suggests that its effects are a bit more complicated than they first appear. Self-efficacy has three main effects, each of which has both a “dark” or undesirable side and a positive or desirable side.

The first effect is that self-efficacy makes students more willing to choose tasks where they already feel confident of succeeding. Since self-efficacy is self-constructed, furthermore, it is also possible for students to miscalculate or misperceive their true skill, and the misperceptions themselves can have complex effects on students’ motivations.

A second effect of high self-efficacy is to increase a persistence at relevant tasks. If you believe that you can solve crossword puzzles, but encounter one that takes longer than usual, then you are more likely to work longer at the puzzle until you (hopefully) really do solve it. This is probably a desirable behavior in many situations, unless the persistence happens to interfere with other, more important tasks. What if you should be doing homework instead of working on crossword puzzles?

Third, high self-efficacy for a task not only increases a person’s persistence at the task, but also improves their ability to cope with stressful conditions and to recover their motivation following outright failures. Suppose that you have two assignments—an essay and a science lab report—due on the same day, and this circumstance promises to make your life hectic as you approach the deadline. You will cope better with the stress of multiple assignments if you already believe yourself capable of doing both of the tasks, than if you believe yourself capable of doing just one of them or (especially) of doing neither.

Self-Efficacy and Learned Helplessness

If a person’s sense of self-efficacy is very low, he or she can develop learned helplessness, a perception of complete lack of control in mastering a task. The attitude is similar to depression, a pervasive feeling of apathy and a belief that effort makes no difference and does not lead to success. Learned helplessness was originally studied from the behaviorist perspective of classical and operant conditioning by the psychologist Martin Seligman (1995). The studies used a somewhat “gloomy” experimental procedure in which an animal, such as a rat or a dog, was repeatedly shocked in a cage in a way that prevented the animal from escaping the shocks. In a later phase of the procedure, conditions were changed so that the animal could avoid the shocks by merely moving from one side of the cage to the other. Yet frequently, they did not bother to do so! Seligman called this behavior learned helplessness. In people, learned helplessness leads to characteristic ways of dealing with problems. They tend to attribute the source of a problem to themselves, to generalize the problem to many aspects of life, and to see the problem as lasting or permanent. In other words, they display a fixed mindset. More optimistic individuals, in contrast, are more likely to attribute a problem to outside sources, to see it as specific to a particular situation or activity, and to see it as temporary or time-limited.

Growth mindset and self-efficacy are closely related but slightly different. For optimal success, students need both self-efficacy (belief in their ability to accomplish a task) coupled with a growth mindset (belief that with effort, their ability to accomplish that task will improve).

Licenses and Attributions:

Original content: CC BY Attribution:

College of Canyons Learning to Learn Chapter 2.1: https://drive.google.com/file/d/17EelmmpaWNPFujiI3aRjleWsJPqozro0/view

Hovden, J., Nguyen, A., & Ortega, A. (2020). Motivation. In Learning to Learn. College of the Canyons.

OpenStax College Success Concise Chapter 1.4. Access for free at: https://openstax.org/books/college-success-concise/pages/1-4-its-all-in-the-mindset

Baldwin, A. (2023). It’s All in the Mindset. In College Success Concise. OpenStax.

College of Canyons Learning to Learn Chapter 3.3: https://drive.google.com/file/d/17EelmmpaWNPFujiI3aRjleWsJPqozro0/view

Hovden, J., Nguyen, A., & Ortega, A. (2020). Self-Efficacy. In Learning to Learn. College of the Canyons.

Modifications: Figures and tables renumbered.