7 Expressivity in Gesture

Lesley Mann

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, students will

- Identify and practice manipulating six categories of gesture choice

- Apply gesture choices to musical examples, justified by score analysis

Beyond Time-Keeping and Traffic Patterns

Thus far, we’ve primarily concentrated on beat patterns for time-keeping, some left hand independence for showing dynamic changes, and traffic direction elements such as preps, cues, and releases. We can group most of that into the umbrella of [mechanical movement which requires a lot of physical coordination but little critical thought about musical decisions.] Now that you’ve also begun to look critically at the musical score, it’s time to begin thinking about expressivity in the conducting gesture in order to advance from a time-keeper to an artistic conductor.

In the following exercise, drag the seven elements of music into the table to rank from top to bottom according to how influential they are in adding expressivity to a performance. (There is no correct answer to this exercise… rather, you are ranking your priorities)

Because expressivity in music generally and in conducting gesture specifically is a subjective topic, conductors may initially find difficulty verbalizing explicit choices that can be made to exemplify musical expression in the gesture. To aid in this endeavor, we’re going to adopt a decision making framework to examine 6 elements of gesture for every musical situation. The framework is easily remembered with the acronym SPIRIT.

Size

Plane Dominance

Ictus Shape

Rebound Speed

Image

Tension

For any passage of music, you can implement choices about each of these elements to develop a gestural vocabulary that portrays musical ideas. Let’s dig in!

Size:

The size of gesture is a simple adjustment to enhance dynamic intent, or to support tempo. Softer dynamics and/or faster tempos require a smaller footprint, while louder dynamics and/or slower tempos can take up more space. Size may also be used within a phrase to show growth and decay. Choosing a size will include the choir of which hinge to prioritize. Small conducting gestures will primarily use the wrist hinge, medium will use both wrist and elbow hinges, and large gestures will usually necessitate including the shoulder hinge.

Plane Dominance:

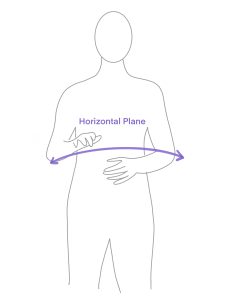

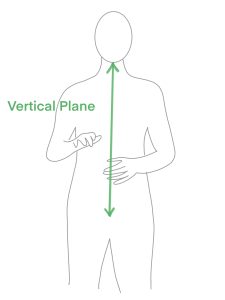

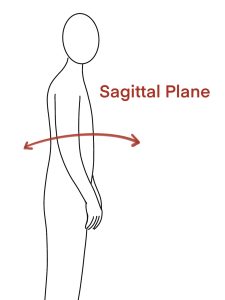

We have three available planes of movement for conducting patterns: Horizontal, Vertical, and Sagittal.

- The horizontal plane is your left to right movement across the body.

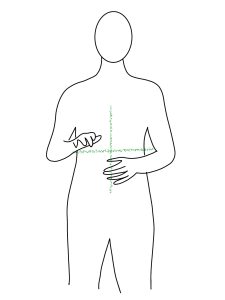

- The vertical plane encompasses the up and down movements from sternum to waist.

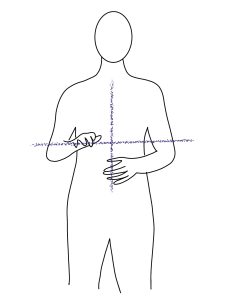

- The Sagittal plane is forward and back in reference to the front of the body, and is what makes conducting a three dimensional endeavor.

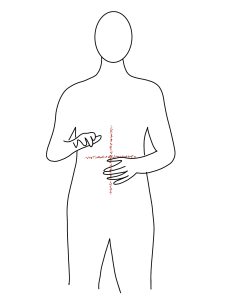

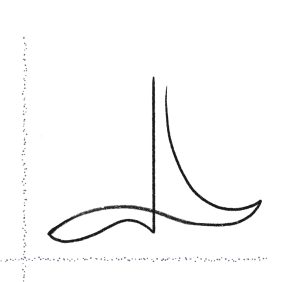

In basic timekeeping mode, we tend to balance the use of horizontal and vertical, rarely using the sagittal plane. When adding expressivity to the gesture, the choice of plane can make a big impact. Articulation (legato, staccato, marcato, etc) is the most common musical element that influences the choice of plane dominance. Below is an image of a neutral gesture in terms of horizontal and vertical plane dominance.

Horizontal plane dominance often represents legato passages. Imagine trailing your fingers across the surface of a body of water from left to right without making large waves. The connection of the hand to the water is a lovely physical representation of connected sound, or legato articulation. Expression terms in music that would evoke a horizontal gesture include Cantabile, Con tenerezza, Dolente, Expressivo, etc.

Vertical plane dominance works well with very active musical passages – staccato or marcato moments – as up and down tends to be perceived as more agitated than side to side. If we continue with the water analogy, when a hand interacts with water from the vertical direction, the resulting splash elicits a much more disconnected or detached character. Expression terms that might imply a vertically dominant plane include Agitato, Animato, Con brio, Scherzando, etc.

The Sagittal plane is only used for emphasis, as it can be difficult to read over an extended time. Try conducting a four pattern where all the beats move forward and back instead of down and up at the ictus point. Ensemble members directly facing a conductor will more easily “read” left-to-right and up-and-down rather than near-and-far. Instead, the sagittal plane will be a great choice for emphatic moments: metric stress, accents, tenutos, and text stress.

Ictus Shape:

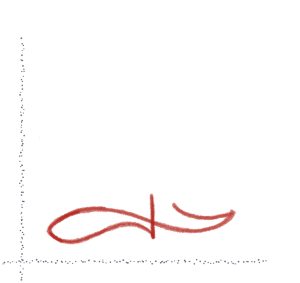

The shape of the ictus can greatly impact the character of the conducting gesture. The shape of a direction change can either be pointed, like a check mark, or rounded, like a swoop.

While expression and articulation will most greatly influence ictus shape, tempo may also play a role. Try conducting a very fast 4 pattern with very swoopy icti – how clearly do you think the ensemble will interpret that tempo?

Expressive Icti

Rebound Speed:

The speed at which a rebound travels away from the ictus is another interesting factor to consider when modifying the gesture for expressivity. Clear, easy to read basic timekeeping mode should aim for an even speed away from the ictus, rather than rushing to the top of the beat. Conduct a 4 pattern in both manners – (1) speed evenly distributed from ictus to ictus, and (2) rush to the top of the beat and suspend until time to hit the next ictus. What qualities would you use to describe the differences in those two examples? Consider correlating the rebound speed with the onset or attack of a pitch – do you want the onset to be smooth or aggressive? The speed at which you move from prep to ictus through rebound can support this decision.

Another expressive option that falls within this category is Melding. Melds are a pause in time-keeping to illustrate a held note. They often indicate a “carry,” and are characterized by a hand that slowly moves from the moment of pause to the next moment of time keeping. In the example below, the held note in measure 2 will be shown with a down beat followed by a slow movement towards beat 4.

Image:

Image encompasses the ways we communicate non-verbally, outside of the traditional pattern and prep/cues/releases. Facial affect and posture play an important role in transmitting a physical image to the ensemble. Research studies on facial affect offer evidence that neutral facial affect is highly undesirable and off-putting to ensembles. The face offers incredible opportunities to convey expressive intent: eyebrows, eye gaze, cheek muscles (zygomatic arch) and lips can communicate quite effectively. Rather than prescribe options such as a binary choice or a continuum between two extremes as in the other categories, the process for this element is to simply consider what image you want to encode to the ensemble.

Tension:

The final decision to make in this framework concerns resistance throughout the gesture. Tension is used as the heading here so that it makes a neat acronym in conjunction with the other decisions, but Resistance is the more nuanced descriptor of the concept. Take your hand and move it from side to side as if a great force is pushing back, or as if you are moving through molasses. What musical effect might that elicit if incorporated into a conducting gesture? Now move your hand through the air with utter freedom. What musical effect might that elicit?

Competency Quiz

SPIRIT in Practice

With the individual elements of the SPIRIT framework in place, you can now consider how to apply them in practical situations.

Scenario 1: Piano – Legato – Adagio

Scenario 2: Mezzo-Forte – Animato – Allegro

Final Reflection Assignment

Watch the opening movement of Leonard Bernstein conducting the Mozart Requiem. Reflect on how his conducting reflects his musical intention, using the SPIRIT framework as a guide. Begin the video at 6:20.