2 Defining “Abortion”

Abortion might personally affect you or someone you know: you or a partner, spouse, relative or friend may have had an abortion, have considered abortion, or will have an abortion. But what is an abortion? There are a number of common definitions, some of which are better and others which are worse:

- Definition 1: An abortion is the murder of an unborn baby or child.

- Definition 2: An abortion is the intentional termination of a fetus to end a pregnancy.

- Definition 3: An abortion is the intentional killing of a fetus to end a pregnancy.

Definition 3 is best. We’ll explain why after we show the problems with the first two definitions.

2.1 “Murdering Babies”

Definition 1 is common with certain groups of people, but even people who believe abortion is wrong should reject it.

“Murder” means “wrongful killing,” and so this definition implies that abortion is wrong by definition, which it isn’t. This definition implies that to know that abortion is wrong, we’d just need to reflect on the meaning of the word, and not give any reasons to think it is wrong. Murder is wrong by definition, but to know that any particular killing is murder, we need arguments. (Compare someone who calls the death penalty murder: we know it’s killing, but is it wrongful killing? We can’t just appeal to the definition of “murder”: we’d need arguments that the death penalty involves wrongful killing.) This definition also means that someone who claims that abortion is not wrong says that “Wrongful killing is not wrong,” which makes no sense. We can even call this a “question-begging” definition, since it assumes that abortion is wrong, which can’t be assumed. So this definition is problematic, even if abortion is wrong.

Definition 1 also describes fetuses as “babies” or “children.” While people are usually free to use words however they want, people can say things that are false: calling something something doesn’t mean it’s really that thing. And the beginnings of something are usually not that thing: a pile of lumber and supplies is not a house; fabric, buttons and thread are not a shirt, and an embryo or early fetus is not a baby or child. To see this, do a Google image search for “babies” and “children” and “fetal development” and “embryonic development.” What (and who) you see in these searches, although related and similar in some ways, are very different: if someone says they want a baby, they aren’t saying they want a month-old fetus.

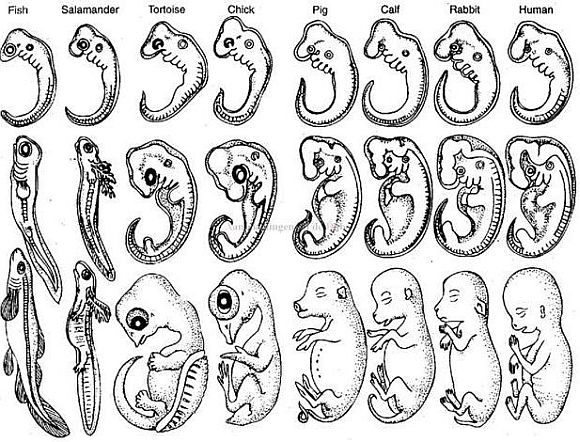

And doing a Google image search for “fetuses of different animals” will bring images like this:

“Baby” rabbits and turtles aren’t at the top of images like this, and neither are “baby” humans. So it’s false and misleading to call embryos and early fetuses “babies” or “children.”

Defining abortion in terms of “babies” seems to again result in a “question-begging” definition that assumes that abortion is wrong, since it is widely and correctly believed that it’s wrong to kill babies. We understand, however, that it’s wrong to kill babies because we think about born babies who are conscious and feeling and have other baby-like characteristics: these are the babies we have in mind when we think about the wrongness of killing babies, not early fetuses. Describing early fetuses as “babies” characterizes them either as something they are not or assumes things that need to be argued for, which is misleading, both factually (in terms of what fetuses are like) and morally (insofar as it’s assumed that the rules about how babies should be treated clearly and straightforwardly apply to, say, embryos).

Part of the problem with this definition is that words like “babies” and “children” elicit strong emotional responses. Babies and children are associated with value-laden terms such as innocence, vulnerability, preciousness, cuteness, and more. When we refer to unborn human beings as fetuses, people sometimes become defensive because they see the word “fetus” as cold and sterile. But “fetus” is merely a helpful, and accurate, name for a stage of development, as is “baby,” “child,” “adolescent,” and “adult.” Distinguishing different stages of human development doesn’t commit anyone to a position on abortion, but it does help us understand what an abortion is.

In sum, defining abortion in terms of “murdering babies” is a bad definition: it misleads and assumes things it shouldn’t. Even those who think that abortion is wrong should not accept it.

2.2 “Termination”

The second definition describes abortion as an intentional action. This is good since a pregnant woman does not “have an abortion,” in the sense we are discussing here, if her pregnancy ends because of, say, a car accident. And “spontaneous abortions” or miscarriages are not intentional actions that can be judged morally: they just happen.

Definitions, however, are supposed to be informative, and the vague word “termination” doesn’t inform. If someone had literally no idea what an abortion was, it would be fair for them to ask what’s exactly involved in a “termination” of a pregnancy. A discussion between persons A and B, where B knows nothing about abortion, might go like this:

- A: “There is a pregnant woman (or girl) who does not want to have a baby, a living baby, obviously. And so we are going to do something to something inside her—that is developing into that living baby—so she does not have that baby. The action we are going to do is the ‘termination.’”

- B: “That something inside her, developing into that living baby, is it living?”

- A: “Yes. It started from a living egg and sperm cell.”

- B: “So you are making something living not living, right? That sounds like killing something, right?”

Person B’s reasoning seems correct: abortions do involve killing. The word “termination” obscures that fact and so makes for an unclear definition. This doesn’t make the definition wrong; to “terminate” something means to end it in some way, and abortion ends the development of a fetus. But it doesn’t say how abortion ends that development and so is not ideal.

Why might someone accept this definition? Probably because they are reasoning this way:

Killing is wrong. So if abortion is killing, then it’s wrong. But I don’t believe that abortion is wrong, or I am unsure that abortion is wrong, so I don’t want to call it a ‘killing,’ since that means it’s wrong.

The problem here is the first step. Not all killing is wrong. Lots of killing is perfectly fine and raises no moral issues at all: killing mold, killing bacteria, killing plants, killing fleas, killing random cells and tissues (even ones that are human, say cheek cells or skin cells), and more. We don’t even need to observe that it’s sometimes not wrong to kill adult human beings to make the point that not all killing is wrong.

This means that it’s not problematic to define abortion in terms of “killing.” The important questions then are, “Is abortion wrongful killing, or killing that’s not wrong?” and “When, if ever, might abortion be wrongful killing and when, if ever, might it be permissible killing? And why?”

2.3 “Killing”

A final definition understands abortion in terms of an intentional killing of a fetus to end a pregnancy.[1] This definition is accurate, informative since it tells us how the fetus would be “terminated,” and morally-neutral: it doesn’t assume that the killing involved in abortions is not wrong or that it’s wrong. This is a good definition.[2]

[1] We accept here that contraceptive measures are not abortifacients. Here “contraception” is understood as any measure that prevents fertilization or implantation. Abortion is understood as the killing of an already-implanted, developing fetus.

[2] Later, however, we will see that there are reasons to define abortion as the intentional withholding of what a fetus needs to live to end a pregnancy. This definition can be developed from some insights into what the right to life seems to involve.