6 Ion Channels

Learning Objectives

Understand:

- The nature of ions

- The nature of ion channels

- The modes of gating ion channels

- The movement of ions across membranes

What are Ions?

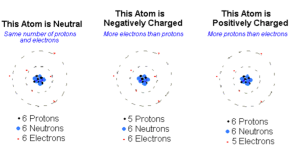

Before considering ion channels in greater detail, we need to clearly define ions. Although I have already been talking about ions, let’s review. Ions are atoms or molecules of atoms in which one or more of the atoms possess either fewer or more electrons than protons, creating a net charge, either negative or positive. There are many different ions in nature. Fortunately, we only need to pay attention to four: Na+, K+, Cl–, and Ca2+. These four ions are responsible for essentially all of the signaling carried out by neurons.

Each ion is a unique atom, which creates some of its uniqueness (e.g. K+ is much smaller than Na+), but its most salient feature is its valence. This refers to its net charge. For Na+ and K+, the valence is plus 1. For Cl– it is negative 1 and for Ca2+ it is plus 2. The ion’s valence determines how it will behave in an electric field. That is, what it will do in the presence of a voltage difference. More about this later, but for now you should know that positive ions will move from higher to lower voltage and negative ions from lower to higher.

What are Ion Channels?

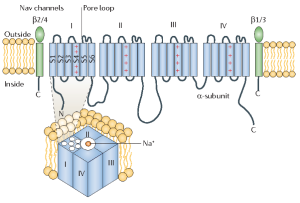

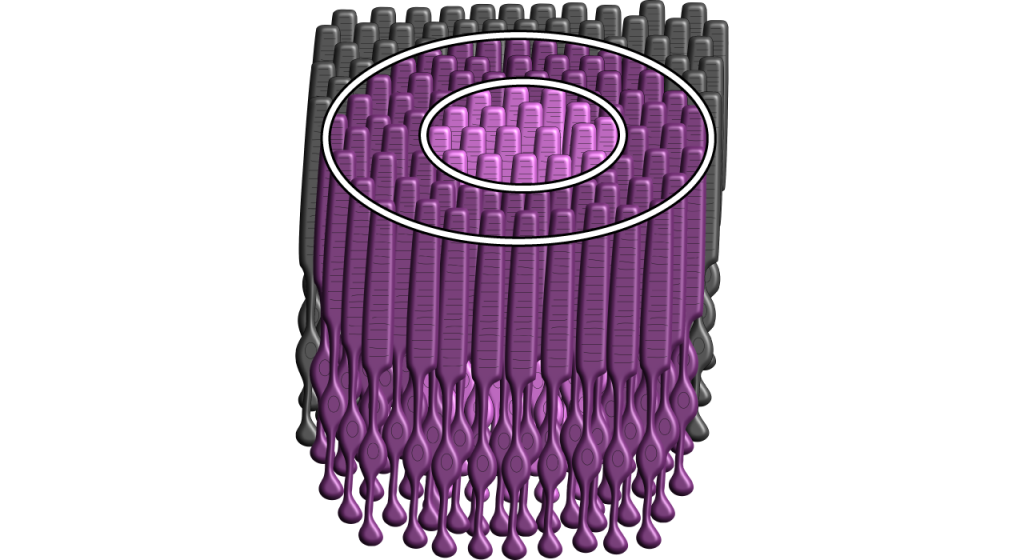

I introduced ion channels in the previous chapter. Let’s now look at them in greater detail. As you might deduce, ion channels must be integral membrane proteins because they span the membrane and you might also assume that the membrane-spanning regions take on the shape of an alpha (α) helix. Recall that a stretch of ~20 hydrophobic amino acids in the shape of an α helix will cross the membrane once. Ion channels contain multiple membrane-spanning regions which arrange themselves in the membrane so that they form a channel or a pore through which the ion can diffuse.

The picture above is a representation of a voltage-gated Na+ channel. For our discussion, you can ignore the green structures. These are subunits that modify the function of the Na+ channel, but are not essential. The part of the protein in blue forms the ion channel. The blue cylinders, labelled S1 – S6, are each α-helices that span the membrane. Notice that they are part of a long string of amino acids that contains 4 similar domains (I, II, III, IV). At this point, if you are really paying attention, you may recognize a problem. If membrane-spanning regions contain all hydrophobic amino acids, why don’t they scare or chase ions away? Hydrophobicity, whether created by lipids or proteins is still hydrophobicity and ions are like water on steroids, metaphorically speaking. They do not just have polar covalent bonds like water, they have a full ionic charge. What gives?

This question puzzled neuroscientists for many years until they figured out that the rule mentioned previously – that proteins must form an α-helix while in the membrane – has exceptions. Specifically, they discovered that the stretch of amino acids connecting S5 and S6 dips into the membrane and forms the pore through which ions pass. Mutations in this part of the protein, that is, changing just a few of the amino acids, can convert the channel to a K+ channel. The interactions between the channel and the ions that creates the selectivity filter take place in this pore loop.

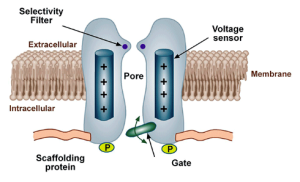

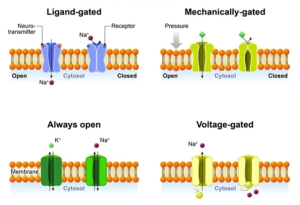

In addition to selectivity filters, many ion channels also have gates. Just as gates on fences can either be open or closed, the gates on ion channels can either be open or closed. What causes these gates to open or close? I am glad you asked. There are three types of gates.

The first type are voltage-gated, such as in the voltage-gated Na+ channel we have just been considering. As the name suggests, these channels are opened (or closed) by changes in the voltage across the membrane. How can voltage do that? Well, as we will discuss in the next chapter, any change in the voltage experienced by an ion will cause the ion to move. If this ion happens to be an amino acid that is part of an ion channel, its movement, albeit slight, can be enough to open (or close) the channel. If you return to the schematic diagram of the V-gated Na+ channel above, you will notice that one of the membrane-spanning helices, S4, is marked with positive charge. Approximately every four amino acids in S4 contains a positive charge. Because of the arrangement of an α-helix, these amino acids line up on the same side of the helix and create a dense source of positive charge. Thus, a change in voltage across the membrane exerts a strong force on S4. The slight movement of S4 gets transmitted to other parts of the channel, resulting in an opening of the pore. Mutations in S4 which remove the positive amino acids eliminate the channels sensitivity to voltage.

The second type is ligand-gated. The channel is opened (or closed) by the binding of a chemical, called a ligand in this case. This is how neurotransmitters act on target cells. By binding to a part of the channel that acts as a receptor, the channel responds by changing its shape and thereby either opening or closing. Just as with voltage-gated channels, the binding of the chemical (ligand) move the protein ever so slightly, but enough to open or close the pore.

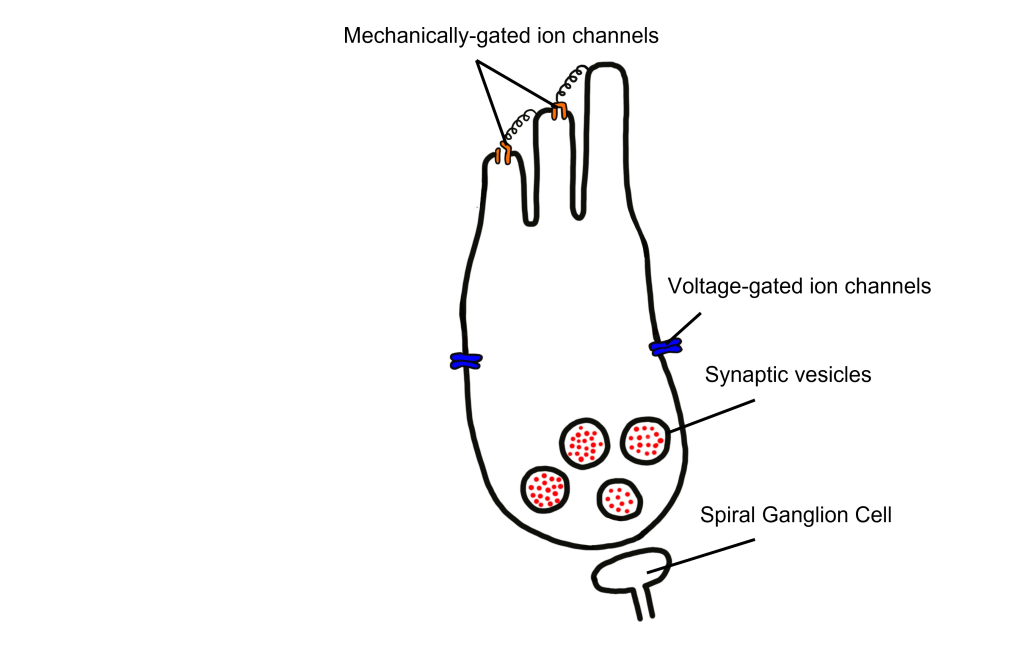

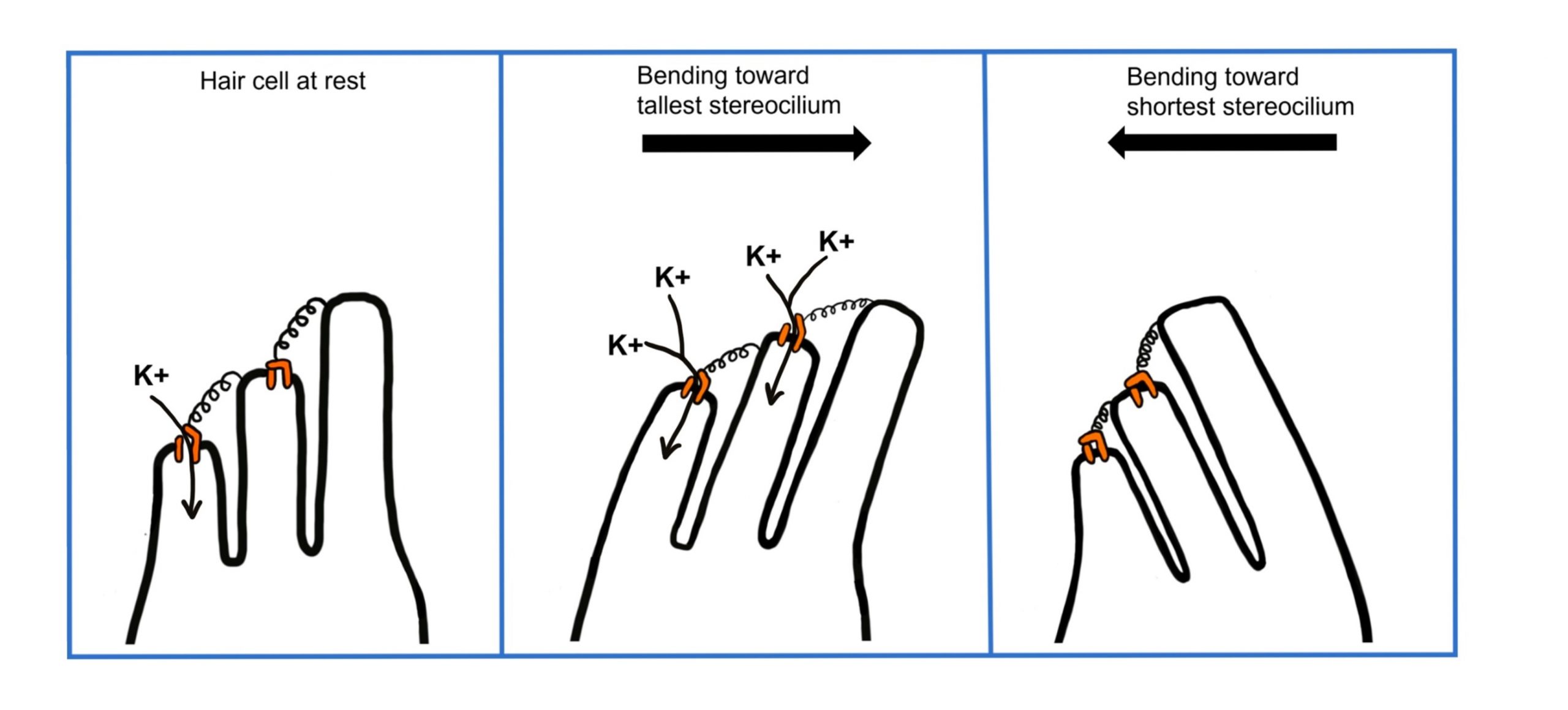

The simplest type to understand are the mechanically-gated ion channels. The gates in these channels are opened or closed by physical pressure. That is, the gates are either pulled or pushed open by an external force. Such channels are found in sensory cells that respond to physical stimuli. For example, the tiny bug crawling up your leg right now is pushing on skin cells in your leg and this pressure opens up ion channels that activate touch sensory receptors. The activated touch receptors then activate neurons that carry the message up to your brain so you can respond appropriately by either swatting the bug away or gently moving it to a safe location (if you are a Buddhist monk).

Ion movement across a membrane

Ion channels control ion movement across the cell membrane because the phospholipid bilayer is impermeable to the charged atoms. When the channels are closed, no ions can move into or out of the cell. When ion channels open, however, then ions can move across the cell membrane.

Gradients Drive Ion Movement

Ions move in predictable ways. Concentration (chemical) and electrical gradients drive ion movement. The chemical gradient refers to the natural process by which a high concentration of a substance, given enough time, will eventually diffuse to a lower concentration and settle evenly over the space. Ions will diffuse from regions of high concentration to regions of low concentration. Diffusion is a passive process, meaning it does not require energy. As long as a pathway exists (like through open ion channels), the ions will move down the concentration gradient.

In addition to concentration gradients, electrical gradients can also drive ion movement. I will describe the proper way to think about electrical gradients in the next chapter. For now, it will be sufficient to think of the electrical gradient as a force that acts on charged molecules. Positive ions (e.g. Na+ and K+) are pushed down an electrical gradient, while negative ions (e.g. Cl–) are pulled up the gradient. The combination of these two gradients will be referred to as the electrochemical gradient. Sometimes the concentration and electrical gradients driving ion movement can be in the same direction; sometimes the direction is opposite. The electrochemical gradient is the summation of the two individual gradients and provides a single direction for net ion movement.

When Gradients Balance, Equilibrium Occurs

When the concentration and electrical gradients for a given ion balance—meaning they are equal in strength, but in different directions—that ion will be at equilibrium. Ions still move across the membrane through open channels when at equilibrium, but there is no net movement in either direction, meaning there is an equal number of ions moving into the cell as there are moving out of the cell.

Media Attributions

- AtomCharge_C3

- IonChannel_Structure_C3

- IonChannel_Gates_C3

The Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) functions as the intermediary between the central nervous system (CNS) and the rest of the body, including the skin, internal organs, and muscles of our limbs. The PNS can be divided into three main branches:

- Somatic nervous system

- Autonomic nervous system

- Enteric nervous system

In this chapter, the somatic and autonomic nervous systems will be compared and contrasted. An overview of the enteric nervous system will also be provided.

Somatic vs. Autonomic Nervous System

The somatic and autonomic nervous system differ in their:

- Target/effector organs

- Efferent pathways and the neurotransmitters that are used

- How the target/effector organ responds to the neurotransmitter

Peripheral Nervous System: Somatic Nervous System

The somatic nervous system represents all the parts of the PNS that are involved with the outside environment, either in sensing the environment or acting on it. For example, the nerves that detect pressure or pain on the foot are part of the afferent somatic nervous system. We also think of the somatic nervous system as the branch that sends signals to our skeletal muscles. The nerves that innervate the muscles of the legs as we run are part of the efferent somatic nervous system. The somatic nervous system is also called the “voluntary nervous system” since it is used to cause muscle movement related to intentional actions.

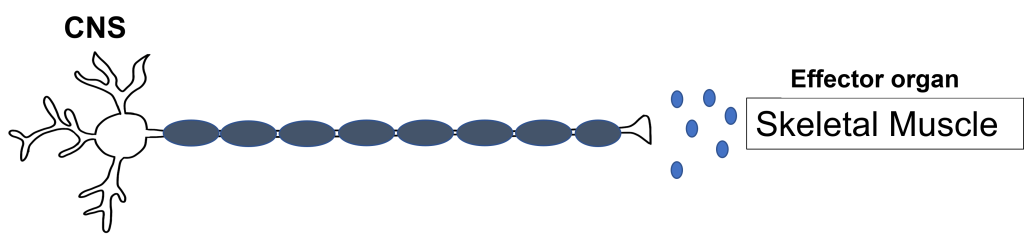

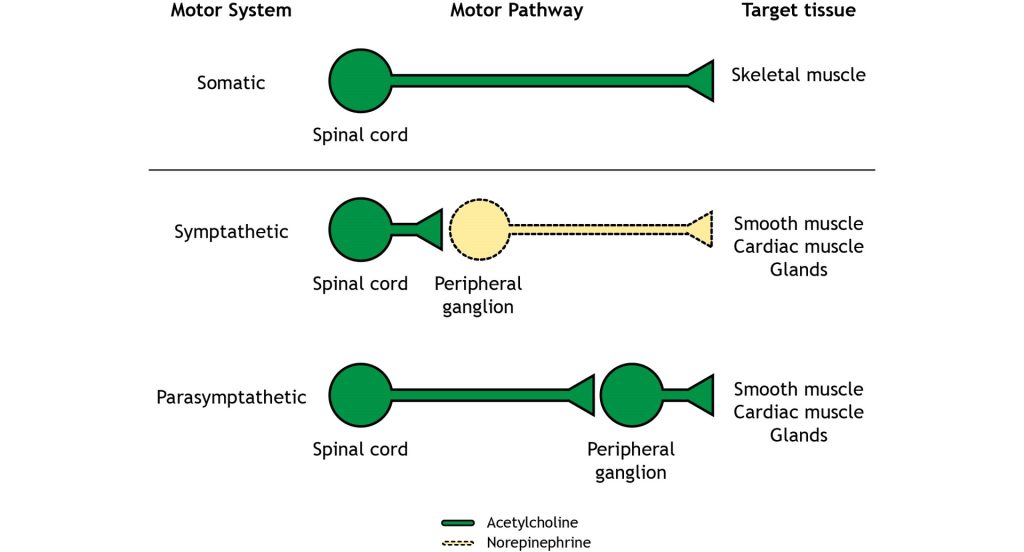

The somatic nervous system has an efferent path from the central nervous system to the target / effector organ that is made up of one neuron. The axon of this neuron is heavily myelinated, which allows for fast delivery of messages. This somatic motor neuron has its cell body in the central nervous system and has an axon that extends all the way to the target/effector organ, which—for the somatic nervous system—will be a skeletal muscle.

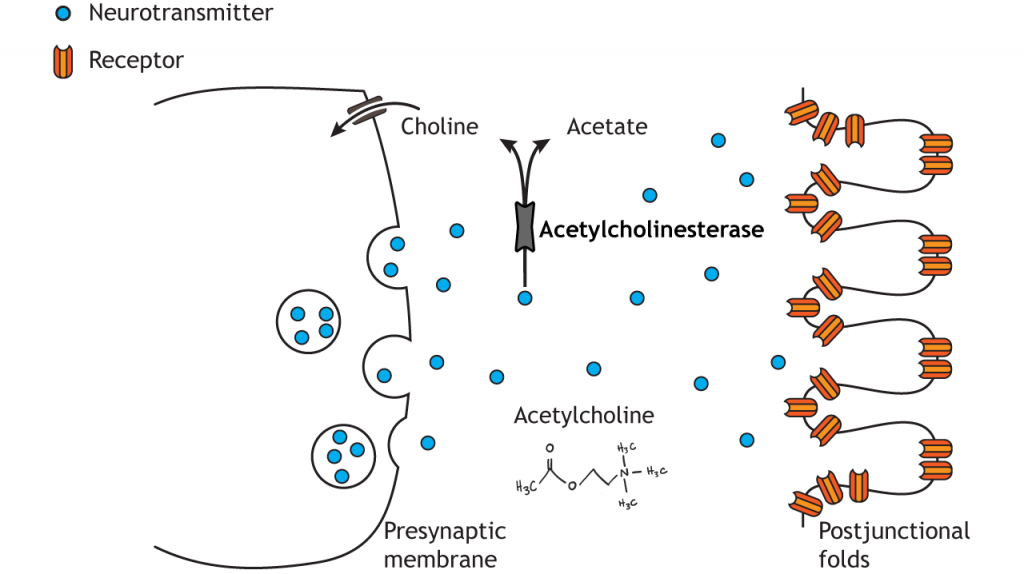

Synapse: Neuromuscular Junction

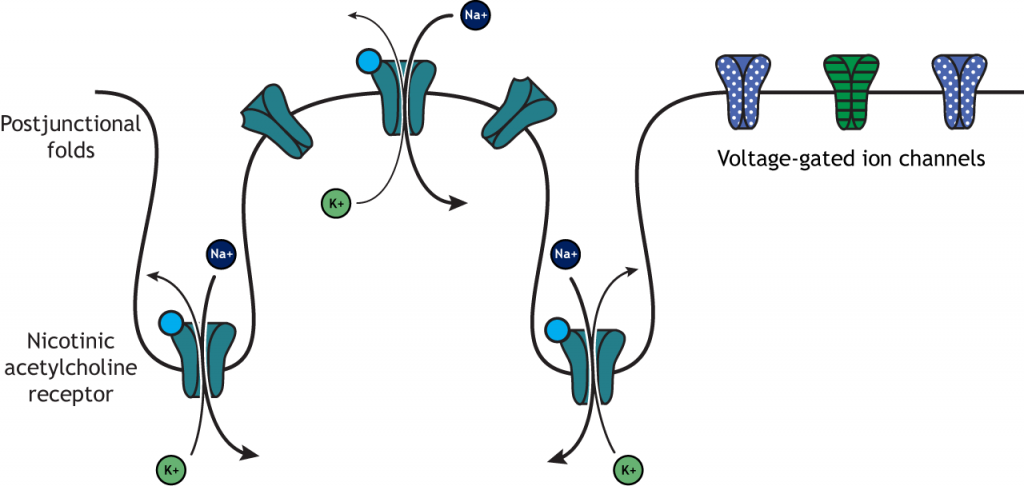

All somatic motor neurons release the same neurotransmitter, acetylcholine, onto the skeletal muscle target/effector organ at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The NMJ is one of the largest synapses in the body and one of the most well-studied because of its peripheral location. Acetylcholine is the neurotransmitter released at the NMJ and it acts upon ligand-gated, non-selective cation channels called nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that are present in postjunctional folds of the muscle fiber. Acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme that breaks down acetylcholine and terminates its action, is present in the synaptic cleft of the neuromuscular junction.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors allow for the influx of sodium ions into the muscle cell. The depolarization will cause nearby voltage-gated channels to open and fire an action potential in the muscle fiber. In a healthy system, an action potential in the motor neurons always causes an action potential in the muscle cell. The action potential leads to contraction of the muscle fiber.

Peripheral Nervous System: Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system encompasses all the branches of the peripheral nervous system that deal with the internal environment. As with the somatic nervous system, the autonomic nervous system is comprised of nerves that detect the internal state as well as nerves that influence the internal organs. The body carries out all sorts of functions and responses unconsciously without any intentional control. It can do so by sending signals to smooth muscles and glands. The signals that cause us to sweat when it is hot, our pupils to dilate when it is dark, and our blood pressure to adjust when we stand up too quickly are all driven by the nerves of the autonomic nervous system.

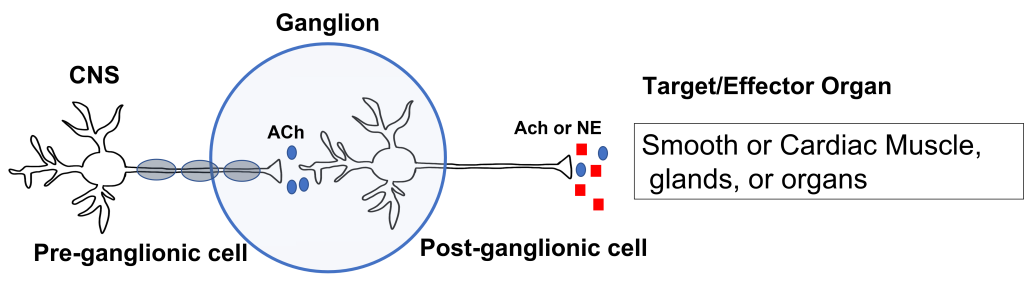

The autonomic nervous system has an efferent path from the central nervous system to the target/effector organ that is made up of a chain of two neurons with a ganglion in the middle. Recall that a ganglion is a collection of neuron cell bodies in the periphery.

The neuron that has its cell body in the central nervous system is called the preganglionic neuron. The preganglionic cell axon is lightly myelinated and extends to a ganglion in the periphery where it synapses on the second neuron in the chain called the postganglionic neuron. The postganglionic neuron has its cell body in the ganglion and its unmyelinated axon extends from the ganglion to the target/effector organ, which for the autonomic nervous system will be: smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, glands, or organs.

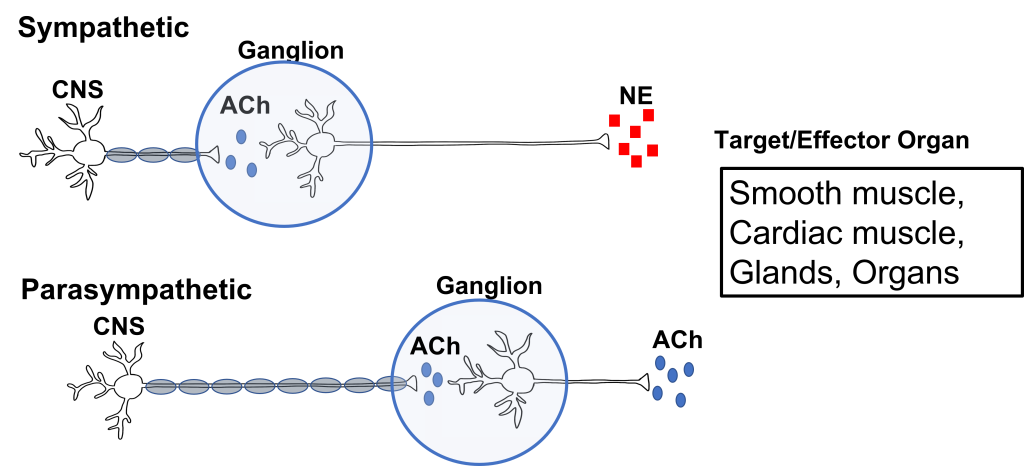

The first synapse happens at the site of the ganglion. All preganglionic cells release acetylcholine onto the postganglionic cells. The acetylcholine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which results in the generation of an excitatory postsynaptic potential for the postganglionic cell body. This effectively passes the message between the preganglionic and postganglionic cells.

The second synapse occurs between the postganglionic cell and the target/effector organ. Postganglionic neurons in the autonomic nervous system release either norepinephrine or acetylcholine (more on this later). These neurotransmitters can have either stimulatory or inhibitory activity at the target organs, dependent on the properties of the postsynaptic receptor that they bind to.

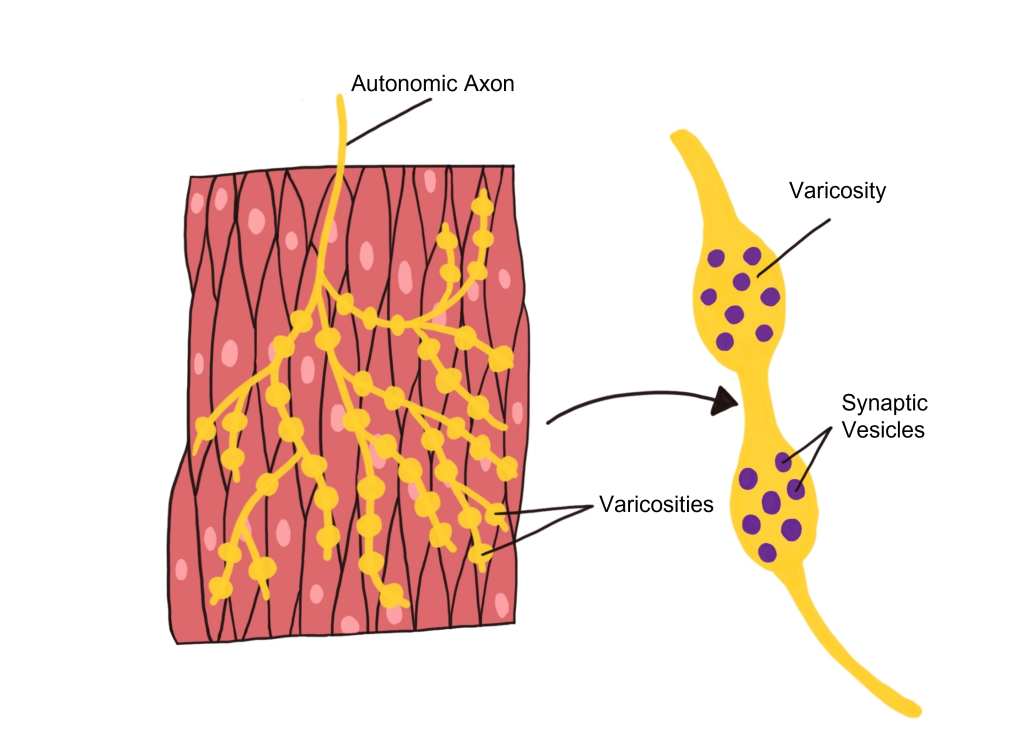

Autonomic Effector Synapse

Within the autonomic nervous system, synapses have a different structure than what is observed at the NMJ of the somatic nervous system. Instead, autonomic axons are highly branched and have enlarged varicosities that are spread along the axon. These varicosities contain synaptic vesicles that are filled with neurotransmitters. The varicosities form synapses 'en passant' (literally meaning 'in passage') with the target organ. These axon branches with varicosities drape over the cells of the target tissue, allowing a single axon branch to affect change over a greater area of the target tissue and better distribute autonomic activation at the target tissue.

Comparing Somatic to Autonomic Nervous System

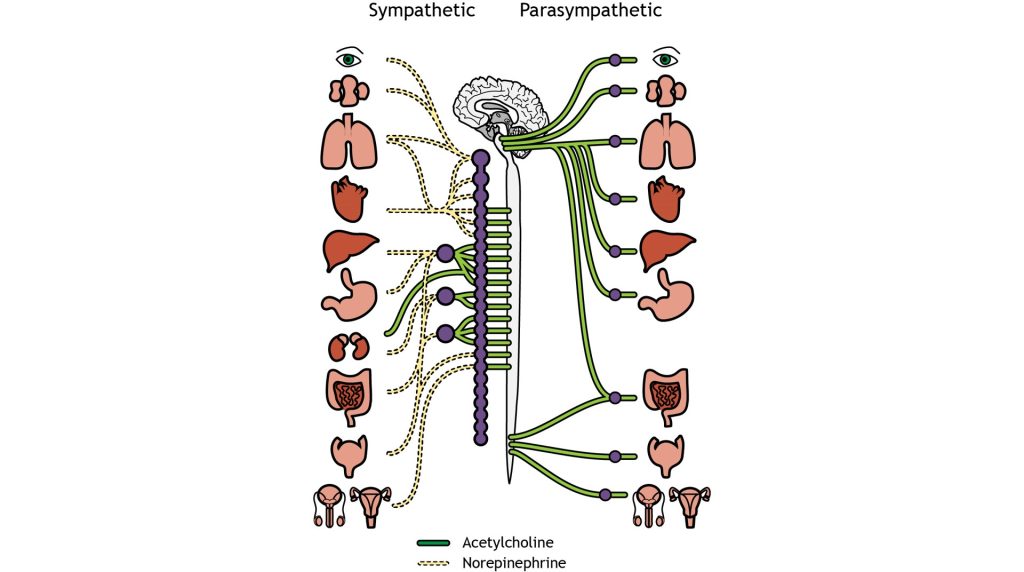

In summary, the somatic nervous system has a one neuron path that originates in the central nervous system. That neuron extends all the way to the skeletal muscle (target tissue) where it releases acetylcholine. The acetylcholine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that cause EPSPs in the muscle fibers and giving a stimulatory effect. The autonomic nervous system (both branches) use a two neuron pathway between the CNS and the target tissues that are smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, glands, and organs. The sympathetic division consists of short presynaptic neurons that synapse on longer postsynaptic neurons in peripheral ganglia that are situated close to the spinal cord. The parasympathetic division consists of long presynaptic neurons that synapse on shorter postsynaptic neurons in peripheral ganglia that are situated close to the target organ. Like the somatic motor system, the primary neurotransmitter in the parasympathetic division is acetylcholine. In the sympathetic division, the preganglionic neuron releases acetylcholine, but the postganglionic neuron releases norepinephrine. The effects of these neurotransmitters at the target tissue can be either stimulatory or inhibitory depending on the properties of the postsynaptic receptor. This information is summarized in the figure and table below.

| Branch of PNS | Efferent Path | Target / Effector Organ | Neurotransmitter Released at Ganglion and Effect | Neurotransmitter Released at Target Organ | Target Organ Response to Neurotransmitter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic | 1 Neuron | Skeletal Muscle | None- No Ganglion | Acetylcholine | Stimulatory |

| Autonomic | 2 Neuron Chain | Smooth / Cardiac Muscle, Glands, Organs | Acetylcholine, excitatory | Acetylcholine or Norepinephrine | Can be stimulatory or inhibitory |

Two Branches of the Autonomic Nervous System

There are two branches of the autonomic nervous system, called the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system, that typically have opposite effects at target tissues.

Consider a scenario in which you encounter a bear on hike through Yellowstone National Park. Your heartrate would likely increase and your breathing rate would increase as you contemplate how to survive your encounter. This complex set of physiological reactions are due to activation of one of the branches of the autonomic nervous system: the sympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system mobilizes a set of physiological changes to a threat that is sometimes called the fight-or-flight response, which is activated when we are faced with a threat, either perceived or real. All of these rapid bodily responses result in the body preparing to attack or defend itself. Increased respiration allows the body to take in more oxygen, and dilation of blood vessels in the muscles allows that oxygen to get to the muscles, which is needed for muscle activation.

Now, consider a completely opposite scenario. You’ve just eaten a large meal and you are spending the evening watching television on your couch. You would probably feel relaxed, satisfied, and more than a little sluggish. A different physiological response is happening, a behavior called the rest-and-digest response. These physiological changes are driven by the other main branch of the autonomic nervous system, called the parasympathetic nervous system.

Targets and Effects of the 2 Branches of the Autonomic Nervous System

The sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system are referred to as antagonistic. These branches are called ‘antagonistic’ because they typically have opposite effects at target tissues.

There is dual innervation at many target organs of the autonomic nervous system. This means that target organs receive connections from both sympathetic and parasympathetic neurons. In a sense, this dual innervation provides both a ‘break’ and an ‘accelerator’ for changing the activity of our internal organs, offering a good amount of control.

Both the sympathetic nervous system and parasympathetic nervous systems influence the internal organs simultaneously. At all times, the heart is getting signals from the sympathetic nervous system which increase heart rate, and signals from the parasympathetic nervous system which decreases heart rate. However, this seesaw-like balance can shift quickly in either direction, such as inducing a sympathetic response if a fearful stimulus is encountered.

| Target Organ | Sympathetic Action | Parasympathetic Action |

|---|---|---|

| Eye | Pupil dilation | Pupil constriction |

| Salivary glands | Prevents saliva secretion | Increases saliva secretion |

| Lungs | Airway dilation | Airway constriction |

| Heart | Increases heart rate | Decreases heart rate |

| Blood vessels | Constriction | No innervation |

| Stomach, liver, intestines, pancreas | Decreases digestion | Increases digestion |

| Kidneys | Sodium and water retention | No innervation |

| Adrenal gland | Increases epinephrine and norepinephrine secretion | No innervation |

| Reproductive organs | Orgasm and ejaculation | Blood vessel dilation leading to erection |

Anatomical Differences between 2 Branches of Autonomic Nervous System

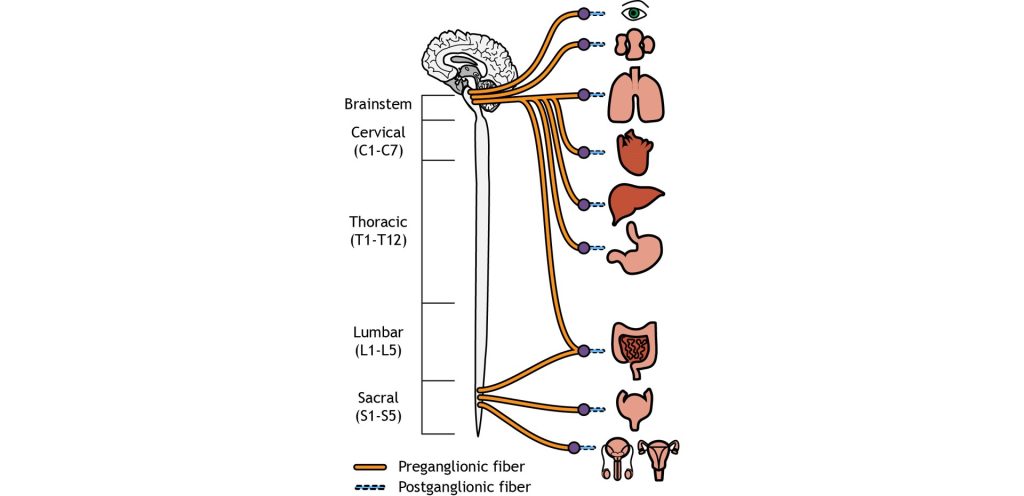

The sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems differ anatomically as well. The sympathetic preganglionic neurons are short and the sympathetic postganglionic neurons are long. The parasympathetic preganglionic neurons are long and the parasympathetic postganglionic neurons are short.

Sympathetic Anatomy

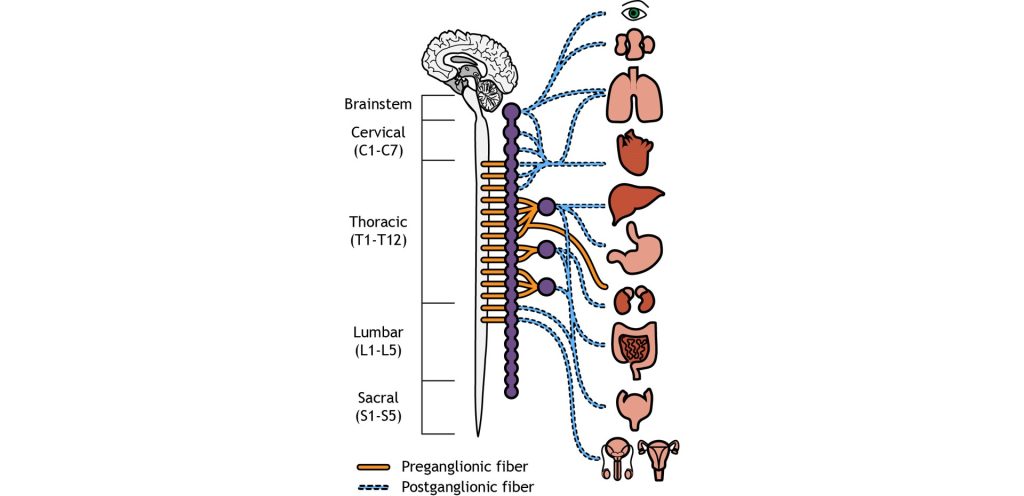

The cell bodies of the preganglionic neurons of the sympathetic nervous system are located in the thoracic and lumbar sections of the spinal cord, so we can use thoracolumbar to describe the site of origin. The axons leave the central nervous system and travel only a short distance to the peripheral ganglion. In the sympathetic system, most of the ganglia are located along the spinal cord in the sympathetic paravertebral chain. A few sympathetic ganglia, called prevertebral, are located slightly more laterally. The preganglionic neurons synapse on the postganglionic neurons in the sympathetic ganglia. The postganglionic neurons then travel the rest of the distance to synapse on the target organs.

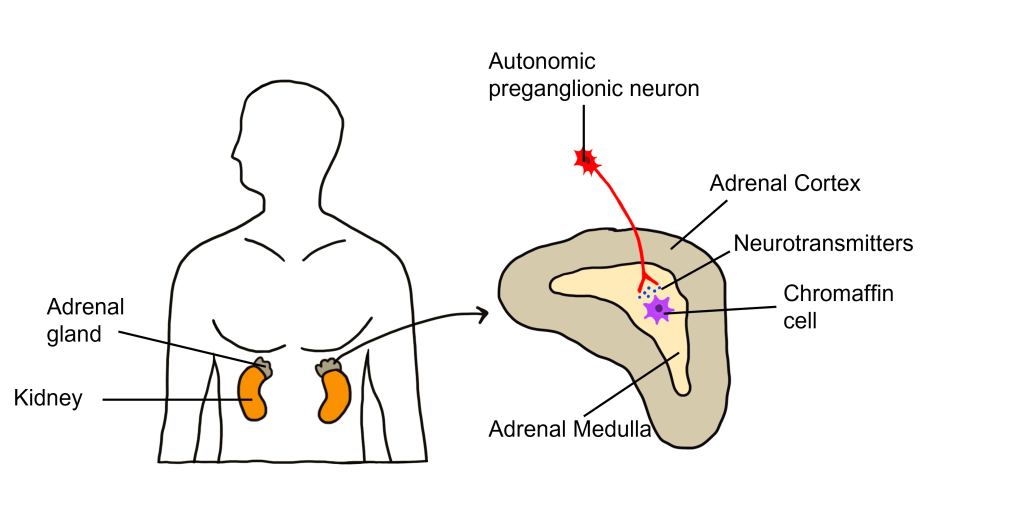

One exception to this structure is the innervation of the adrenal medulla. The adrenal gland is a structure located at the top of each kidney. The gland has an outer portion called the cortex and an inner portion called the adrenal medulla, which is made up of cells called chromaffin cells. The sympathetic preganglionic cell releases acetylcholine at the synapse with the chromaffin cells of the medulla and releases acetylcholine onto the chromaffin cell that is serving as a modified post-ganglionic neuron. Then the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla release epinephrine and norepinephrine into the bloodstream. Within the bloodstream these neurotransmitters can act as hormones affecting change throughout the body leading to a rapid onset of sympathetic activity and sustained activation.

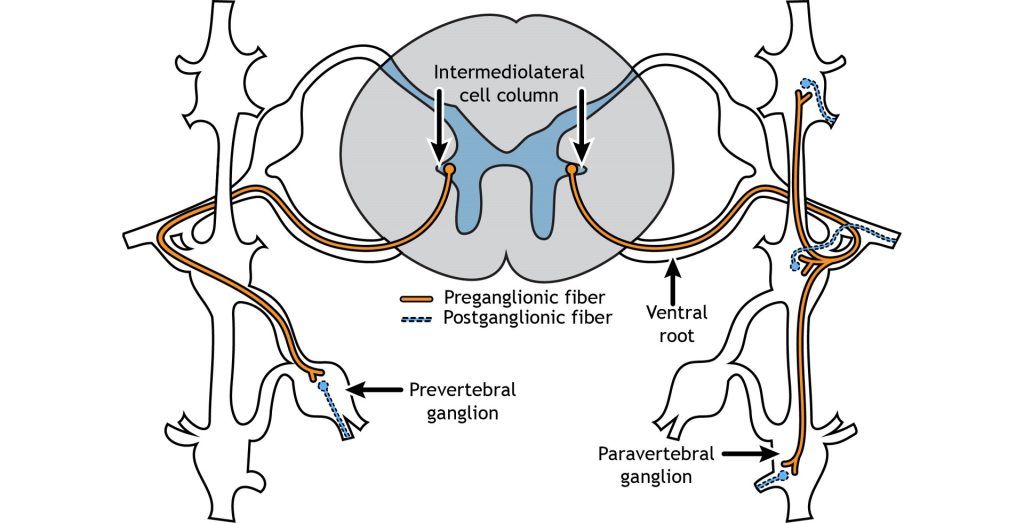

The sympathetic preganglionic cell bodies are located in the intermediolateral cell columns in the lateral horn of the spinal cord, a gray matter region between the dorsal and ventral horns. The neurons send their axons out through the ventral root, and then can take one of multiple pathways. The axon can terminate in the paravertebral ganglion at the same spinal level as the cell body, or the axon can extend up or down the sympathetic chain to synapse on a postganglionic fiber at a different spinal level. Another possible pathway is to enter and exit the sympathetic chain without synapsing and continue on to terminate in a prevertebral ganglion located closer to the target organ.

Parasympathetic Anatomy

On the other hand, parasympathetic neurons originates predominantly in the cervical spinal cord (near the neck), with some signals originating in the sacral areas (near the tail bone). The parasympathetic nervous system usually receives signals from several cranial nerves. Cranial nerve X, also called the vagus nerve innervates multiple bodily organs in the midsection of the body. For the parasympathetic nervous system, the ganglia are located very close to the target tissues. Therefore, the preganglionic neuron must be very long to reach all the way to the ganglion to makes its first synapse. But due to the proximity of the ganglion to the target tissue, the postganglionic neuron is very short.

Neurotransmitters of the Autonomic Nervous System

We have already established that at the first synapse in the chain of autonomic neurons, all preganglionic neurons release acetylcholine, which binds to excitatory nicotinic receptors on the postganglionic neurons. This is true of both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system. However, the two branches of the autonomic nervous system have different effects at target tissues because they use different neurotransmitters that produce either stimulatory or inhibitory effects at target tissues.

The sympathetic postganglionic neurons release norepinephrine at target tissues. Norepinephrine (and epinephrine) binds two major classes of adrenergic receptors: alpha adrenergic receptors and beta adrenergic receptors. The effects of norepinephrine (and epinephrine) can be either excitatory or inhibitory depending on the properties of the postsynaptic receptor.

The parasympathetic postganglionic neurons release acetylcholine at target tissues. The target tissues express muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. The effect of the acetylcholine can be either excitatory or inhibitory depending on the subtype of muscarinic (metabotropic) receptors. The location of function of these transmitters and receptors are critical for clinical use, for example, when treating high blood pressure or sexual dysfunction.

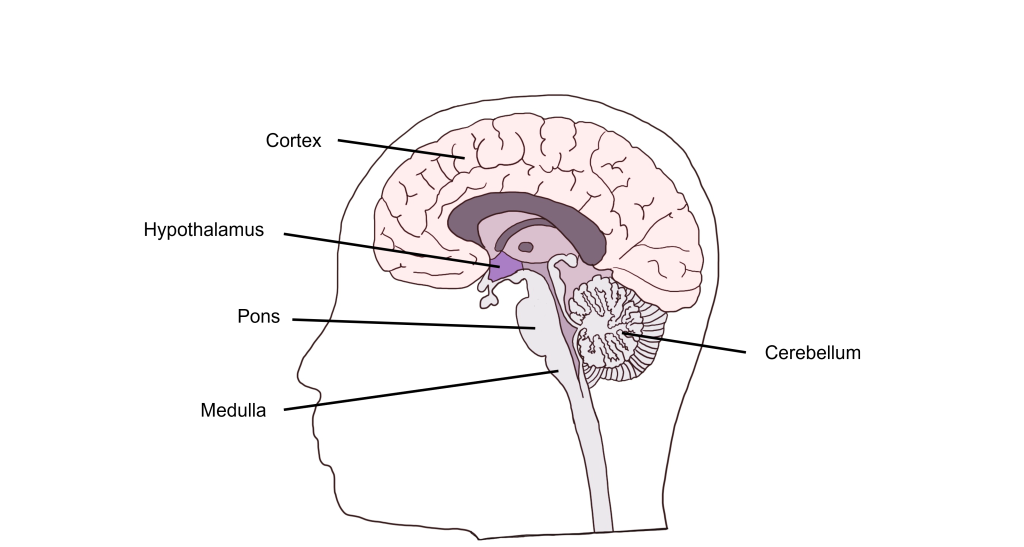

Autonomic Control Centers in the Brain

Visceral functions are regulated through a number of autonomic reflexes, but they can be directly controlled by higher brain areas. Within the brain stem, the medulla most directly controls autonomic activity. The medulla receives most of its information via the vagus nerve (a mixed nerve that contains both sensory and motor fibers). Within the medulla are a variety of control centers that regulate functions such as cardiovascular activity, respiratory rate, vomiting, and swallowing. The pons, another brain stem structure also serves as an autonomic control center for respiration.

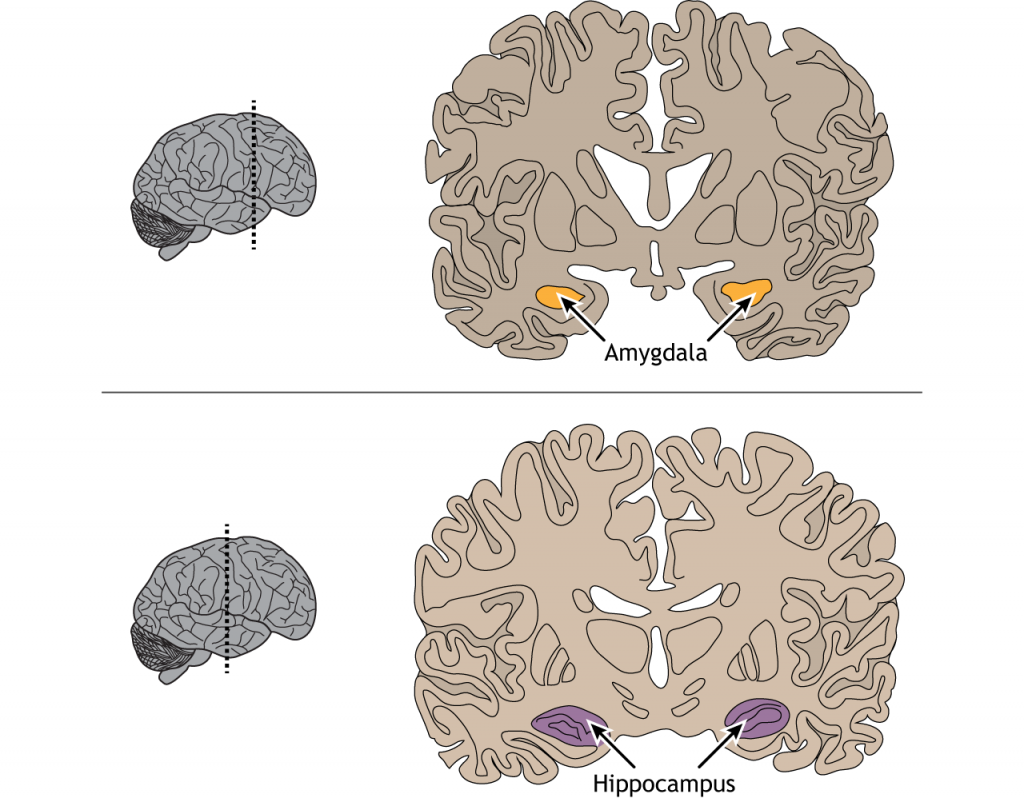

In addition to brain stem structures, there are also higher order brain areas that are important for autonomic control. The hypothalamus can directly regulate the medulla, and is also critical for the regulation of water balance, temperature control, and hunger. The Limbic System, made up of a number of structures including the the hippocampus and amygdala, functions in our expression of emotion. The limbic system structures are responsible for visceral responses associated with emotional states, including blushing, fainting, pallor, nervous cold sweats, racing heart rate, and uneasy feelings in the stomach.

Further, the cerebral cortex and cerebellum also function in autonomic control. The cerebral cortex has been shown to regulate lower brain structures especially in autonomic control associated with emotion and personality. The cerebellum has connections to the medulla that are critical for the control of autonomic functions such as sweating and nausea.

Enteric Nervous System

The internal organs that carry out digestive functions, such as the esophagus, stomach, and intestines, are surrounded by a dense mesh of neurons that regulate their activity. Consisting of half a billion nerve cells, this net of neurons cause the digestive tract to increase or decrease the rate of these processes depending on the body’s demands The enteric nervous system receives signals from both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, and functions without our conscious knowledge. Historically, these digestive functions have been classified as part of the autonomic nervous system, but these responses do not share the same reflex pathway, and the enteric signals can work entirely independent of the vagus nerve, for example.

Key Takeaways

- There are 3 main divisions of the peripheral nervous system: the somatic nervous system, the autonomic nervous system and the enteric nervous system.

- The somatic and autonomic nervous systems different in their efferent path, how they synapse on target tissues, the neurotransmitters that are used, and the action of those neurotransmitters at target tissues.

- The autonomic nervous system can be subdivided into the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

- The sympathetic nervous system is the "fight or flight" system and the parasympathetic nervous system is the "rest and digest" system.

- There are anatomical differences between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system.

- Several brain areas serve as autonomic control centers.

- The enteric nervous system controls the gut and receives connections from both autonomic nervous system branches.

Test Yourself!

Attributions

Portions of this chapter were remixed and revised from the following sources:

- Foundations of Neuroscience by Casey Henley. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

- Open Neuroscience Initiative by Austin Lim. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Humans are remarkably dependent on the visual system to gain information about our surroundings. Consider how tentatively you walk from the light switch to your bed right after turning off the lights!

The visual system is complex and consists of several interacting anatomical structures. Here, we will describe the process of how photons of light from our surroundings become signals that the brain turns into representations of our surroundings.

Properties of Light

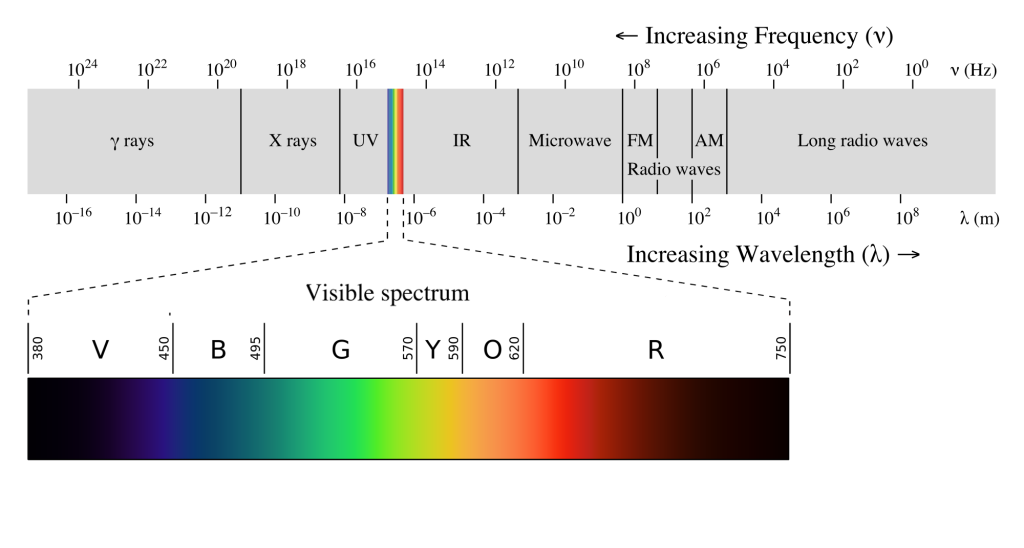

Visual sensation starts at the level of the eye. The eye is an organ that has evolved to capture photons, the elementary particle of light. Photons are unusual because they behave as both particles and as waves, but neuroscientists mostly focus on the wave-like properties. Because photons travel as waves, they oscillate at different frequencies. The frequency at which a photon oscillates is directly related to the color that we perceive.

The human visual system is capable of seeing light in a very narrow range of frequencies on the electromagnetic spectrum. On the short end, 400 nm wavelengths are observed as violet, while on the long end, 700 nm wavelengths are red. Ultraviolet light oscillates at a wavelength shorter than 400 nm, while infrared light oscillates at a wavelength longer than 700 nm. Neither ultraviolet nor infrared light can be detected with our eyes.

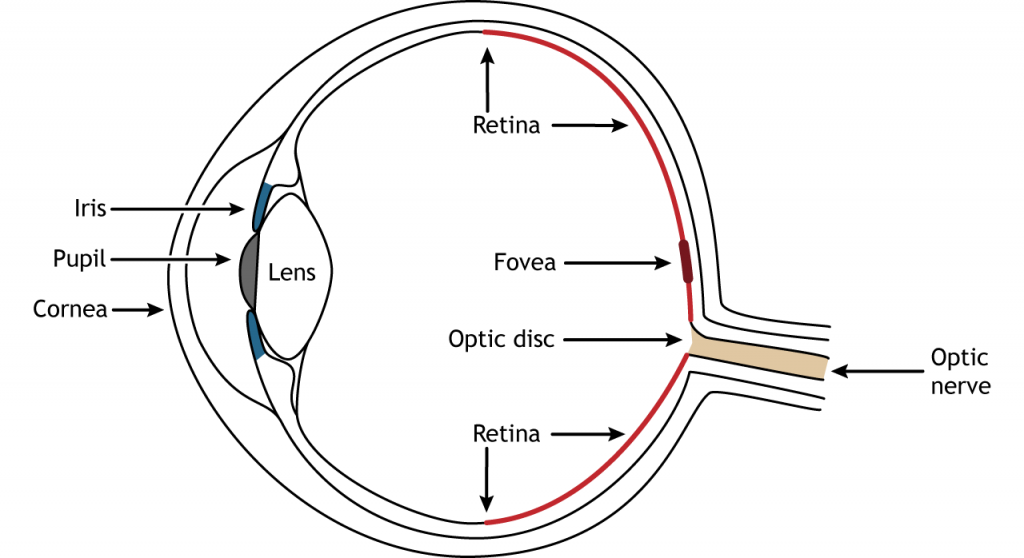

Anatomy of the Eye

Photons pass through several anatomical structures before the nervous system processes and interprets them. The front of the eye consists of the cornea, pupil, iris, and lens. The cornea is the transparent, external part of the eye. The cornea refracts, or bends, the incoming rays of light so that they converge precisely at the retina, the posterior most part of the eye. If the light rays fail to properly converge, a person would be near-sighted or far-sighted, and this would result in blurry vision. Glasses or contact lenses bend light before it reaches the cornea to compensate the cornea’s shape.

After passing through the cornea, light enters through a hole in the opening in the iris at the center of the eye called the pupil. The iris is the colored portion of the eye that surrounds the pupil and along with local muscles that can control the size of the pupil to allow for an appropriate amount of light to enter the eye. The diameter of the pupil can change depending on ambient light conditions. In the dark, the pupil dilates, or gets bigger, which allows the eye to capture more light. In bright conditions, the pupils constricts, or gets smaller, which decreases the amount of light that enters the eye.

The next structure that light passes through is the lens. The lens is located behind the pupil and iris. Like the cornea, the lens refracts light so that the rays converge on the retina. Proper focusing requires the lens to stretch or relax, a process called accommodation. A circular muscle that surrounds the lens, called the ciliary muscle, changes the shape of the lens depending on the distance of the object of focus.

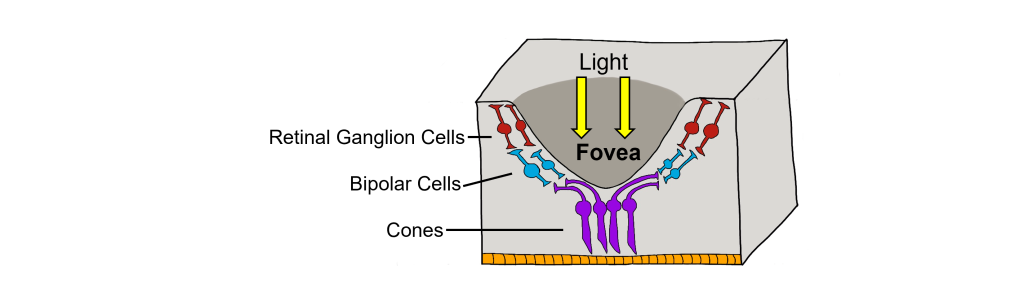

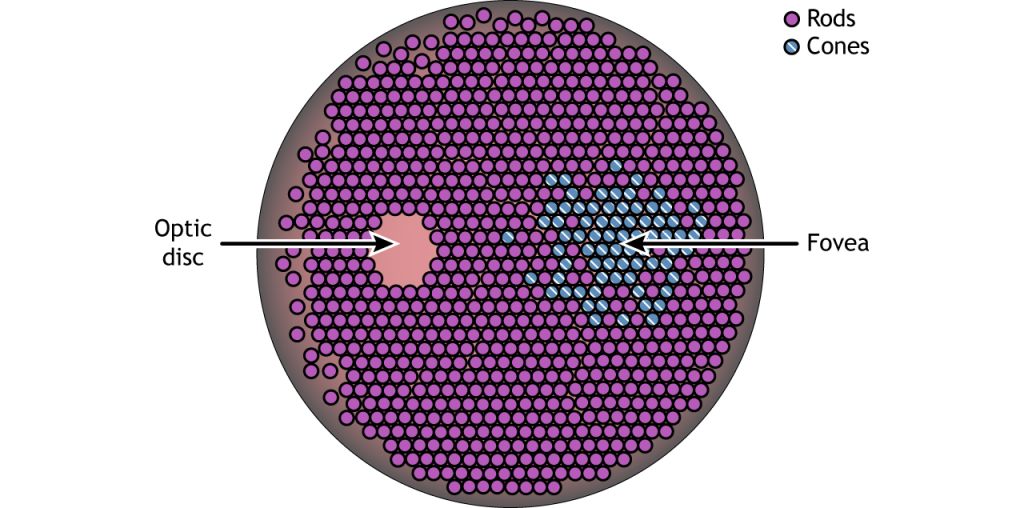

The retina is the light-sensitive region in the back of the eye where the photoreceptors, the specialized cells that respond to light, are located. The retina covers the entire back portion of the eye, so it’s shaped like a bowl. In the middle of the bowl is the fovea, the region of highest visual acuity, meaning the area that can form the sharpest images. The optic nerve projects to the brain from the back of the eye, carrying information from the retinal cells. Where the optic nerve leaves, there are no photoreceptors since the axons from the neurons are coming together. This region is called the optic disc and is the location of the blind spot in our visual field.

Retinal Cells

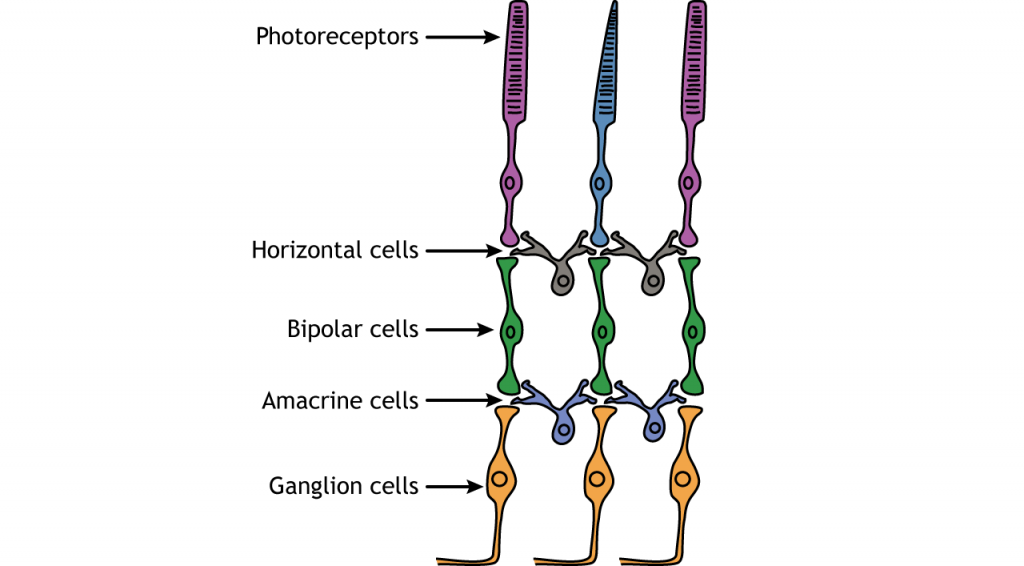

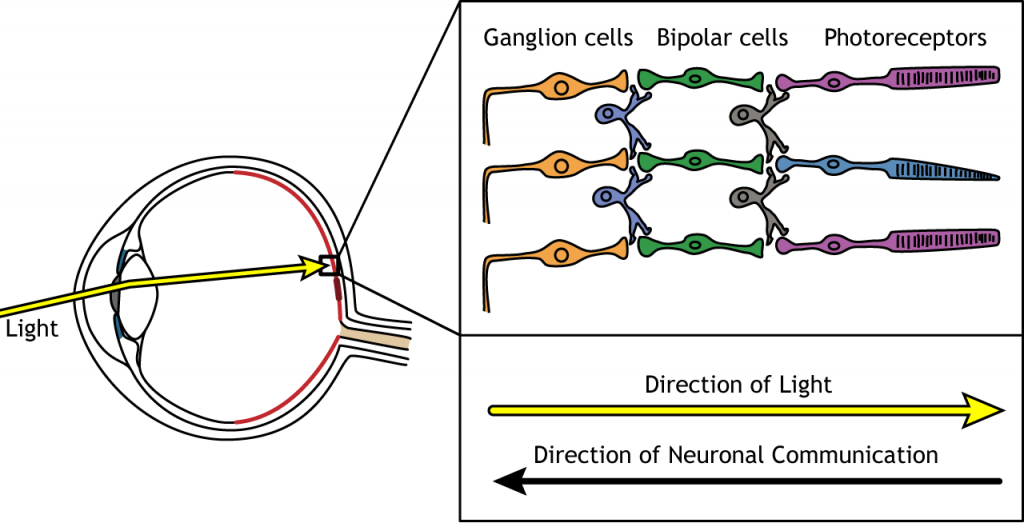

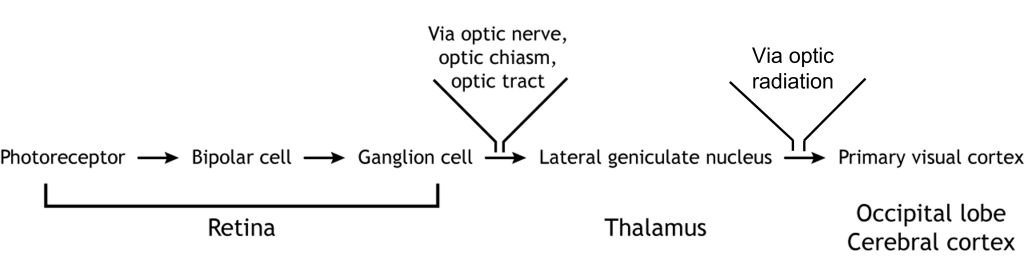

In addition to the photoreceptors, there are four other cell types in the retina. The photoreceptors synapse on bipolar cells, and the bipolar cells synapse on the ganglion cells. Horizontal and amacrine cells allow for communication laterally between the neuron layers.

Direction of Information

When light enters the eye and strikes the retina, it must pass through all the neuronal cell layers before reaching and activating the photoreceptors. The photoreceptors then initiate the synaptic communication back toward the ganglion cells.

Photoreceptors

Photoreceptors are the first cells in the neuronal visual perception pathway. The photoreceptors are the specialized receptors that respond to light. They are the cells that detect photons of light and convert them into neurotransmitter release, a process called phototransduction.

Morphologically, photoreceptor cells have two parts, an outer segment and inner segment. The outer segment contains stacks of membranous disks bounded within the neuronal membrane. These membranous disks contain molecules called photopigments, which are the light-sensing components of the photoreceptors. Hundreds of billions of these photopigments can be found in a single photoreceptor cell. The inner segment contains the nucleus and other organelles. Extending from the inner segment is the axon terminal.

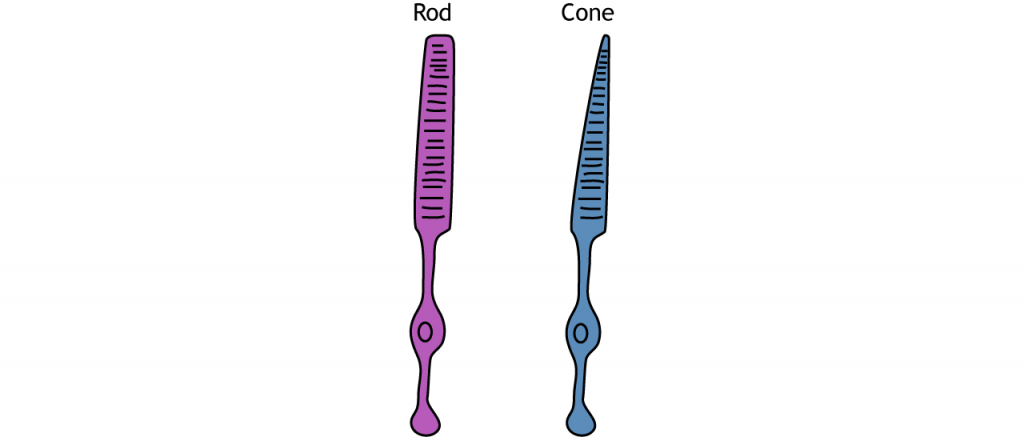

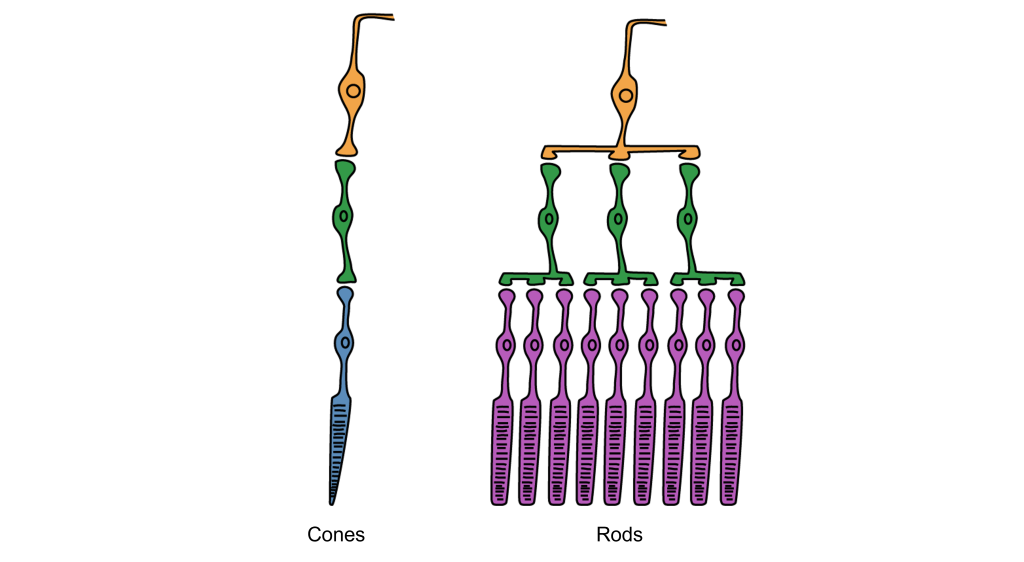

Photoreceptors are classified into two categories, named because of their appearance and shape: rods and cones. Rod photoreceptors have a long cylindrical outer segment that holds many membranous disks. The presence of more membranous disks means that rod photoreceptors contain more photopigments and thus are capable of greater light sensitivity.

Cone photoreceptors have a short, tapered c, and cylindrical outer segment that holds fewer membranous disks than rod photoreceptors. The presence of less membranous disks means that cone photoreceptors contain less photopigments and thus are not as sensitive to light as rod photoreceptors. Cone photoreceptors are responsible for processing our sensation of color (the easiest way to remember this is cones = color). The typical human has three different types of cone photoreceptors cells, with each of these three types tuned to specific wavelengths of light. The short wavelength cones (S-cones) respond most robustly to 420 nm violet light. The middle wavelength cones (M-cones) exhibit peak responding at 530 nm green light, and the long wavelength cones (L-cones) are most responsive in 560 nm red light. Each of these cones is activated by other wavelengths of light too, but to a lesser degree. Every color on the visible spectrum is represented by some combination of activity of these three cone photoreceptors.

The idea that we have two different cellular populations and circuits that are used in visual perception is called the duplicity theory of vision and is our current understanding of how the visual system perceives light. It suggests that both the rods and cones are used simultaneously and complement each other. The photopic vision, uses cone photoreceptors of the retina, and is responsible for high-acuity sight and color vision in daytime. Its counterpart, called scotopic vision, uses rod photoreceptors and is best for seeing in low-light conditions, such as at night. Both rods and cones are used for mesopic vision, when there are intermediate lighting conditions, such as indoor lighting or outdoor traffic lighting at night.

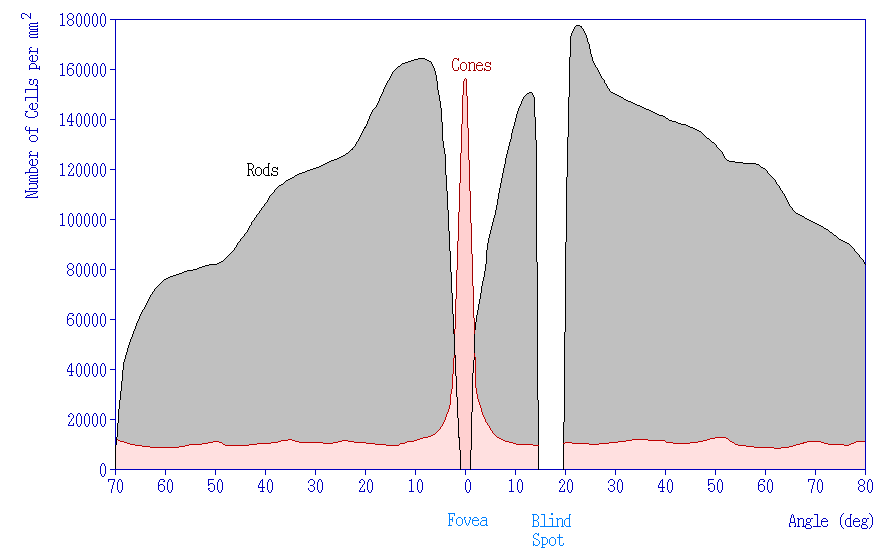

Photoreceptor Density

In addition to having different visual functions, the rods and cones are also distributed across the retina in different densities. Visual information from our peripheral vision is generally detected by our rod cells, which are most densely concentrated outside the fovea. Cone photoreceptor cells allow for high-acuity vision. They are most densely packed at the fovea, corresponding to the very center of your visual field. Despite being the cell population that we use for our best vision, cone cells make up the minority of photoreceptors in the human retina, outnumbered by about 20-times more rod cells.

Synaptic Convergence of Photoreceptors

Rod cells are organized to have high synaptic convergence, where several rod cells (up to 30) feed into a single downstream route of communication (the bipolar cells, to be specific). An advantage of a high-convergence network is the ability to add many small signals together to create a seemingly larger signal. Consider stargazing at night, for example. Each rod is able to detect low levels of light, but signals from multiple rod cells, when summed together, allows you to recognize faint light sources such as a star. A disadvantage of this type of organization is that it is difficult to identify exactly which photoreceptor is activated by the incoming light, which is why accuracy is poor when seeing stimuli in our peripheral vision. This is one of the reasons that we cannot actually read text in our peripheral vision or see the distinct edges of a star. Rod photoreceptors are maximally active in low-light conditions.

Unlike rod cells, cone cells have very low synaptic convergence. In fact, at the point of highest visual acuity, a single cone photoreceptor communicates with a single pathway to the brain. The signaling from low-convergence networks is not additive, so they are less effective at low light conditions. However, because of this low-convergence organization, cone cells are highly effective at precisely identifying the location of incoming light.

Retina: Fovea and Optic Disk

The retina is not completely uniform across the entire back of the eye. There are a few spots of particular interest along the retina where the cellular morphology is different: the fovea and the optic disk.

There are two cellular differences that explain why the fovea is the site of our best visual acuity. For one, the neurons found at the fovea are “swept” away from the center, which explains why the fovea looks like a pit. Cell membranes are made up mostly of lipids, which distort the passage of light. Because there are fewer cell bodies present here, the photons of light that reach the fovea are not refracted by the presence of other neurons. Secondly, the distribution of photoreceptors at the fovea heavily leans toward cone type photoreceptors. Because the cone cells at the fovea exhibit low convergence, they are most accurately able to pinpoint the exact location of incoming light. On the other hand, most of the photoreceptors in the periphery are rod cells. With their high-convergence circuitry, the periphery of the retina is suited for detecting small amounts of light, though location and detail information is reduced.

Another anatomically interesting area of the retina is an elliptical spot called the optic disk. This is where the optic nerve exits the eye. At this part of the retina, there is an absence of photoreceptor cells. Because of this, we are unable to perceive light that falls onto the optic disk. This spot in our vision is called the blind spot.

Phototransduction

The photoreceptors are responsible for sensory transduction in the visual system, converting light into electrical signals in the neurons. For our purposes, to examine the function of the photoreceptors, we will A) focus on black and white light (not color vision) and B) assume the cells are moving from either an area of dark to an area of light or vice versa.

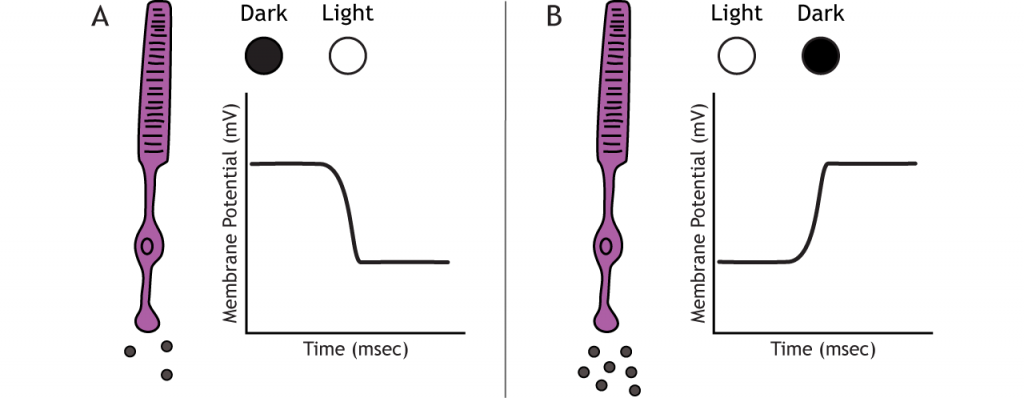

Photoreceptors do not fire action potentials; they respond to light changes with graded receptor potentials (depolarization or hyperpolarization). Despite this, the photoreceptors still release glutamate onto the bipolar cells. The amount of glutamate released changes along with the membrane potential, so a hyperpolarization will lead to less glutamate being released. Photoreceptors hyperpolarize in light and depolarize in dark. In the graphs used in this lesson, the starting membrane potential will depend on the initial lighting condition.

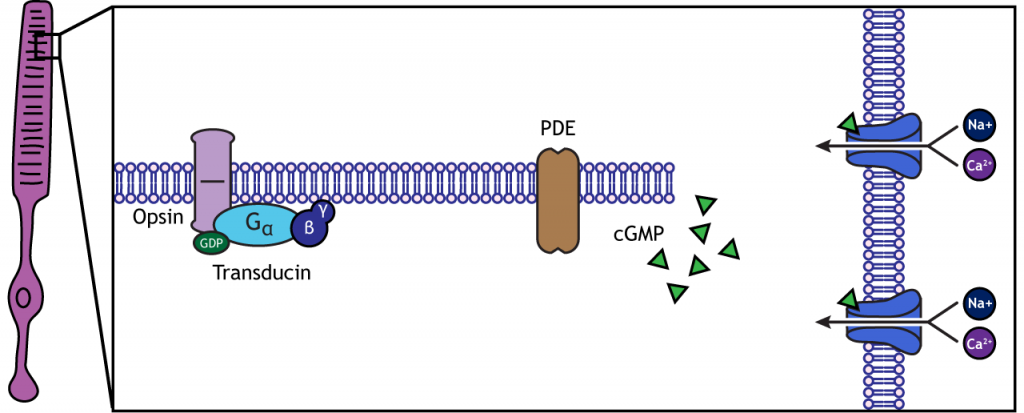

When the photoreceptor moves into the light, the cell hyperpolarizes. Light enters the eye, reaches the photoreceptors, and causes a conformational change in a special receptor protein called an opsin. The opsin receptor has a pre-bound chemical agonist called retinal. Together, the opsin + retinal makes up the photopigment rhodopsin.

When rhodopsin absorbs light, it causes a conformational change in the pre-bound retinal, in a process called “bleaching”. The bleaching of rhodopsin activates an associated G-protein called transducin, which then activates an effector enzyme called phosphodiesterase (PDE). PDE breaks down cGMP in the cell to GMP. As a result, the cGMP-gated ion channels close. The decrease in cation flow into the cell causes the photoreceptor to hyperpolarize.

Animation 29.1. Light reaching the photoreceptor causes a conformational change in the opsin protein, which activates the G-protein transducing. Transducin activates phosphodiesterase (PDE), which converts cGMP to GMP. Without cGMP, the cation channels close, stopping the influx of positive ions. This results in a hyperpolarization of the cell. ‘Phototransduction’ by Casey Henley is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share-Alike (CC BY-NC-SA) 4.0 International License. View static image of animation.

In the dark, the photoreceptor has a membrane potential that is more depolarized than the “typical” neuron we examined in previous chapters; the photoreceptor membrane potential is approximately -40 mV.

Rhodopsin is not bleached, thus the associated G-protein, transducin, remains inactive. As a result, there is no activation of the PDE enzyme, and levels of cGMP within the cell remain high. cGMP binds to cGMP-gated sodium ion channels, causing them to open. The open cation channels allow the influx of sodium and calcium, which depolarize the cell in the dark.

Transmission of Information within Retina

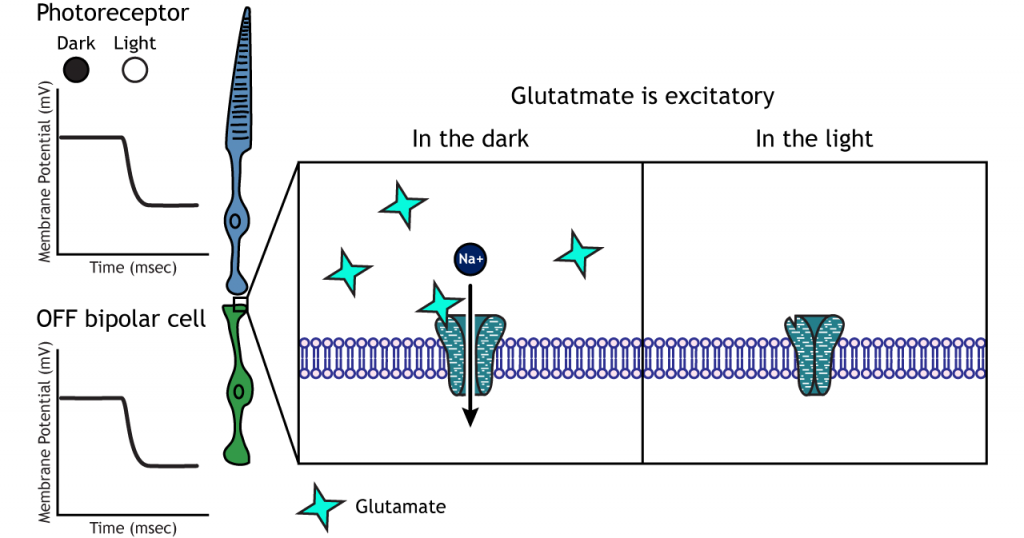

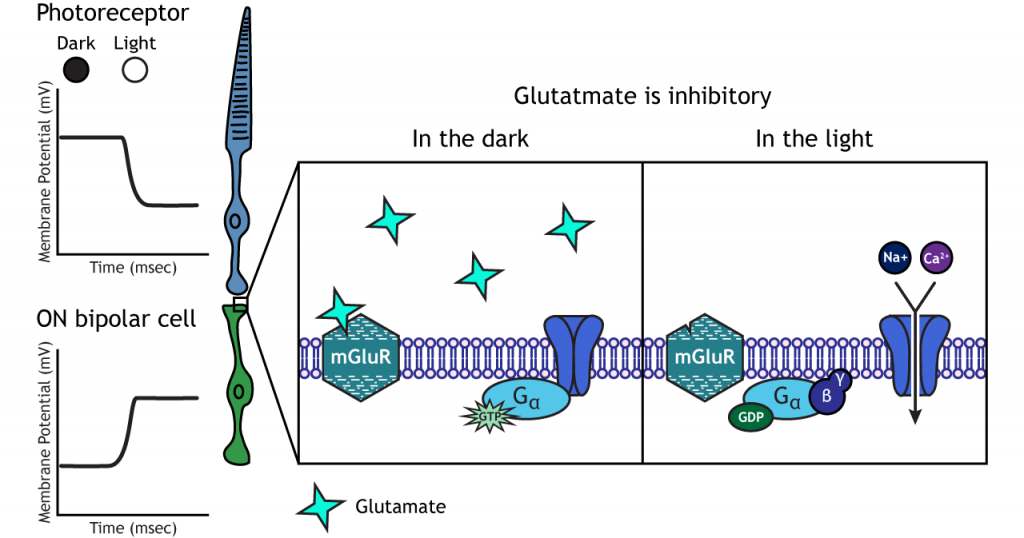

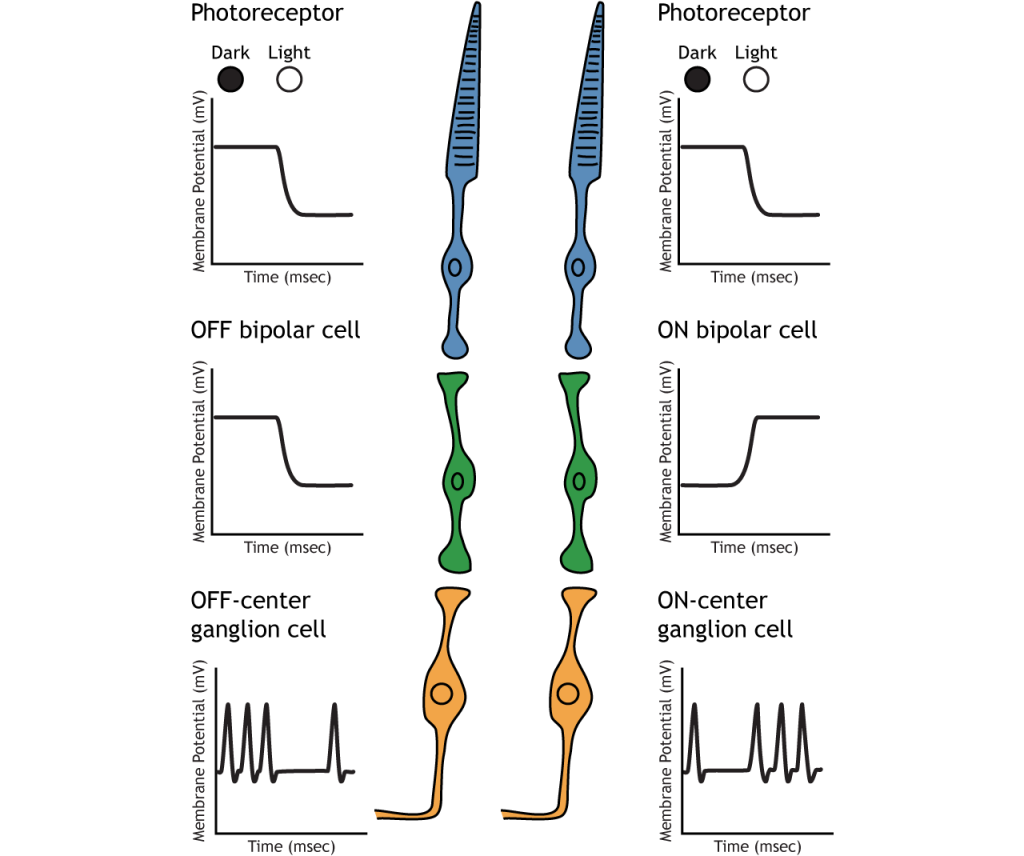

Photoreceptors synapse onto bipolar cells in the retina. There are two types of bipolar cells: OFF-center bipolar cells and ON-center bipolar cells. These cells respond in opposite ways to the glutamate released by the photoreceptors because they express different types of glutamate receptors. Like photoreceptors, the bipolar cells do not fire action potential and only respond with graded postsynaptic potentials.

OFF-center Bipolar Cells

In OFF-center bipolar cells, the glutamate released by the photoreceptor is excitatory. OFF-center bipolar cells express ionotropic glutamate receptors. In the dark, the photoreceptor is depolarized, and thus releases more glutamate. The glutamate released by the photoreceptor activates the ionotropic receptors, and sodium can flow into the cell, depolarizing the membrane potential. In the light, the photoreceptor is hyperpolarized, and thus does not release glutamate. This lack of glutamate causes the ionotropic receptors to close, preventing sodium influx, hyperpolarizing the membrane potential of the OFF-center bipolar cell. One way to remember this is that OFF-center bipolar cells are excited by the dark (when the lights are OFF).

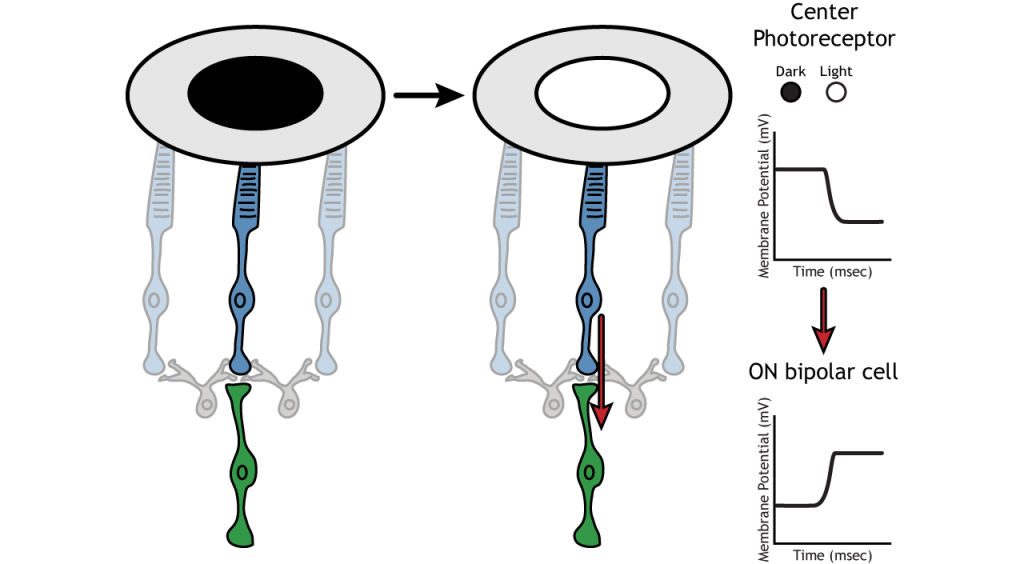

ON-center Bipolar Cells

In ON-center bipolar cells, the glutamate released by the photoreceptor is inhibitory. ON-center bipolar cells express metabotropic glutamate receptors. In the dark, the photoreceptor is depolarized, and thus releases more glutamate. The glutamate released by the photoreceptor binds to the metabotropic receptors on ON-center bipolar cells, and the G-proteins close cation channels in the membrane, stopping the influx of sodium and calcium, hyperpolarizing the membrane potential. In the light, the photoreceptor is hyperpolarized, and thus does not release glutamate. The absence of glutamate results in the ion channels being open and allowing cation influx, depolarizing the membrane potential. You can remember that ON-center bipolar cells are excited by the light (when the lights are ON).

Retinal Ganglion Cells

Retinal ganglion cells are the third and last cell type that directly conveys visual sensory information, receiving inputs from the bipolar cells. OFF-center and ON-center bipolar cells synapse on OFF-center and ON-center ganglion cells, respectively. The axons of the retinal ganglion cells bundle together and form the optic nerve, which then exits the eye through the optic disk. Retinal ganglion cells are the only cell type to send information out of the retina, and they are also the only cell that fires action potentials. The ganglion cells fire in all lighting conditions, but it is the relative firing rate that encodes information about light. A move from dark to light will cause OFF-center ganglion cells to decrease their firing rate and ON-center ganglion cells to increase their firing rate.

Receptive Fields

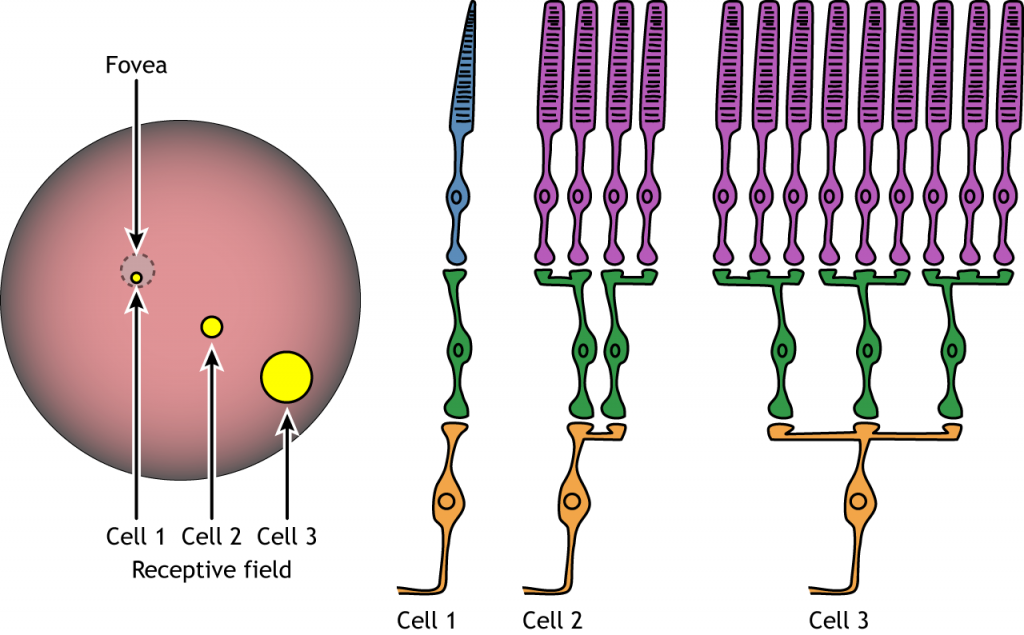

Each bipolar and ganglion cell responds to light stimulus in a specific area of the retina. This region of retina is the cell’s receptive field. Receptive fields in the retina are circular.

Size of the receptive field can vary. The fovea has smaller receptive fields than the peripheral retina. The size depends on the number of photoreceptors that synapse on a given bipolar cell and the number of bipolar cells that synapse on a given ganglion cell, also called the amount of convergence.

Receptive Field Example

Let’s use an example of an ON-center bipolar cell to look at the structure of receptive fields in the retina. The bipolar and retinal ganglion cell receptive fields are divided into two regions: the center and the surround. The center of the receptive field is a result of direct innervation between the photoreceptors, bipolar cells, and ganglion cells. If a light spot covers the center of the receptive field, the ON-center bipolar cell would depolarize, as discussed above; the light hits the photoreceptor, it hyperpolarizes, decreasing glutamate release. Less glutamate leads to less inhibition of the ON bipolar cell, and it depolarizes.

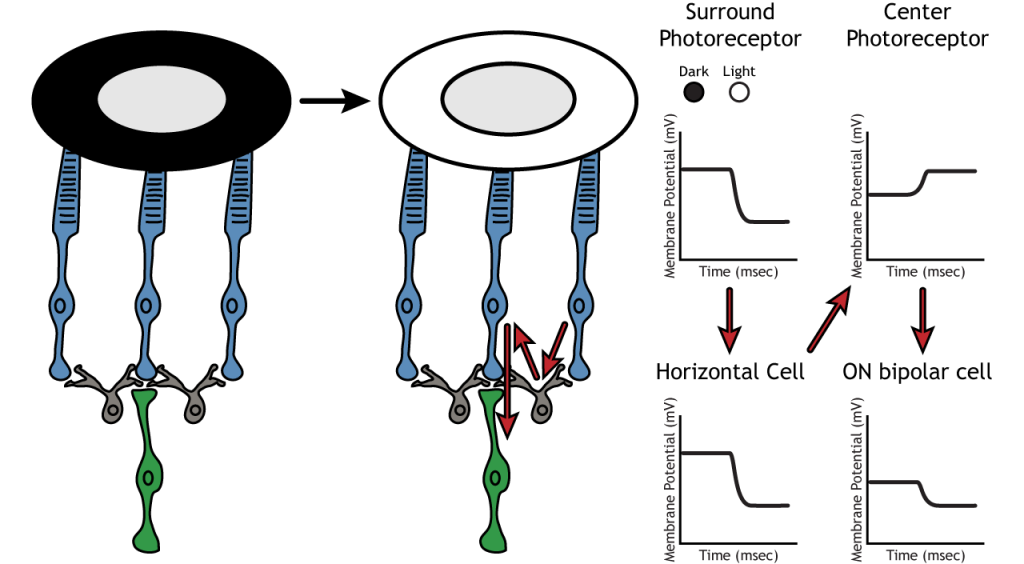

The surround portion of the receptive field is a result of indirect communication among the retinal neurons via horizontal and amacrine cells. The surround has an opposing effect on the bipolar or ganglion cell compared to the effect of the center region. That is to say, that the center and surround of the receptive field are opposite to each other. So, an ON-center bipolar or ganglion cell, can also be referred to as an “ON-center OFF-surround cell”, and an OFF-center bipolar or ganglion cell can also be referred to as an “OFF-center ON-surround cell”.

Therefore, if light covers the surround portion, the ON-center bipolar cell would respond by hyperpolarizing. The light would cause the photoreceptor in the surround to hyperpolarize. This would cause the horizontal cell to also hyperpolarize. Horizontal cells have inhibitory synaptic effects, so a hyperpolarization in the horizontal cell would lead to a depolarization in the center photoreceptor. The center photoreceptor would then cause a hyperpolarization in the ON-center bipolar cell. These effects mimic those seen when the center is in dark. So, even though the center photoreceptor is not directly experiencing a change in lighting conditions, the neurons respond as if they were moving toward dark.

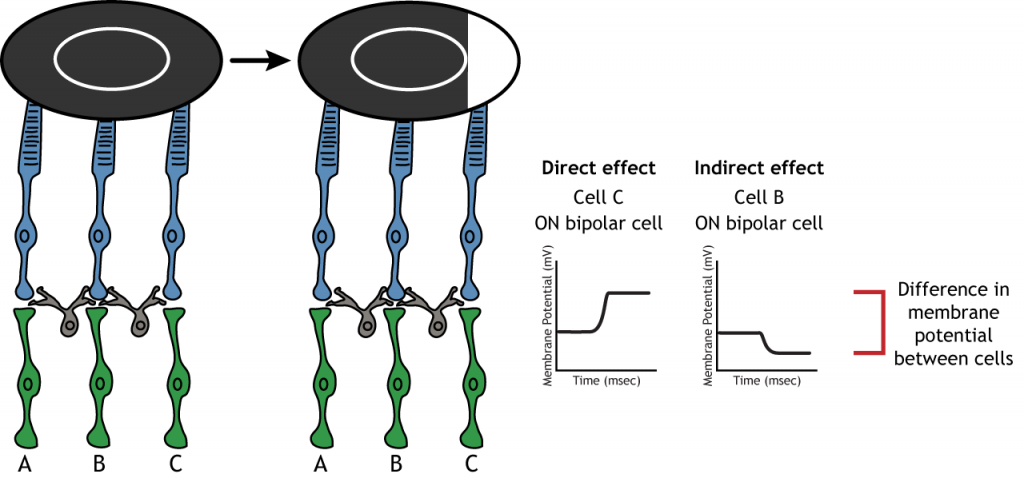

Lateral Inhibition

The center-surround structure of the receptive field is critical for lateral inhibition to occur. Lateral inhibition is the ability of the sensory systems to enhance the perception of edges of stimuli. It is important to note that the photoreceptors that are in the surround of one bipolar cell would also be in the center of a different bipolar cell. This leads to a direct synaptic effect on one bipolar cell while also having an indirect effect on another bipolar cell.

Although some of the images used here will simplify the receptive field to one cell in the center and a couple in the surround, it is important to remember that photoreceptors cover the entire surface of the retina, and the receptive field is two-dimensional. Depending on the level of convergence on the bipolar and ganglion cells, receptive fields can contain many photoreceptors.

Key Takeaways

- Photoreceptors and bipolar cells do not fire action potentials

- Photoreceptors hyperpolarize in the light

- ON bipolar cells express inhibitory metabotropic glutamate receptors

- OFF bipolar cells express excitatory ionotropic glutamate receptors

- Receptive fields are circular, have a center and a surround, and vary in size

- Receptive field structure allows for lateral inhibition to occur

Test Yourself!

Additional Review

- Compare and contrast rods and cones.

- Compare and contrast the fovea and the optic disc.

Attributions

Portions of this chapter were remixed and revised from the following sources:

- Foundations of Neuroscience by Casey Henley. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

- Open Neuroscience Initiative by Austin Lim. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

In this chapter we will learn about how the information from the retina is processed centrally within the brain.

Visual Fields

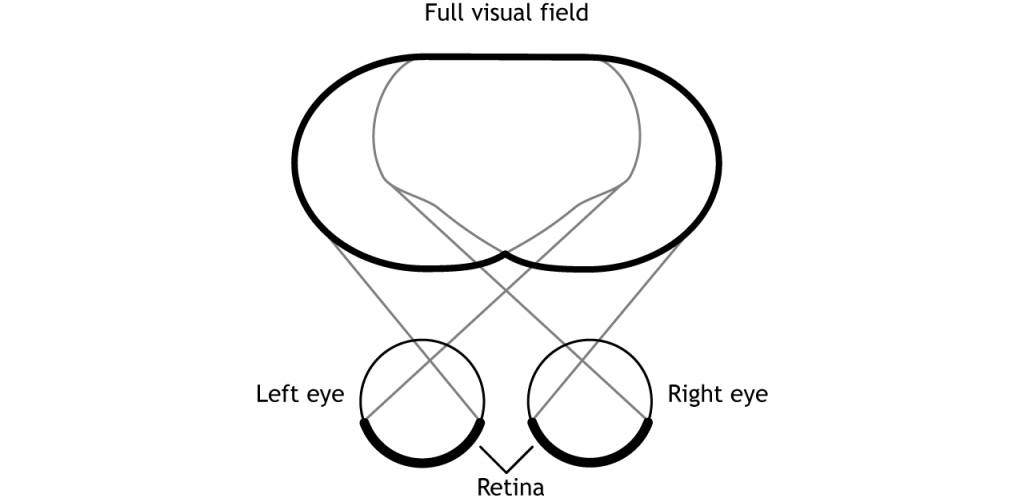

Before learning the pathway that visual information takes from the retina to the cortex, it is necessary to understand how the retina views the world around us. The full visual field includes everything we can see without moving our head or eyes.

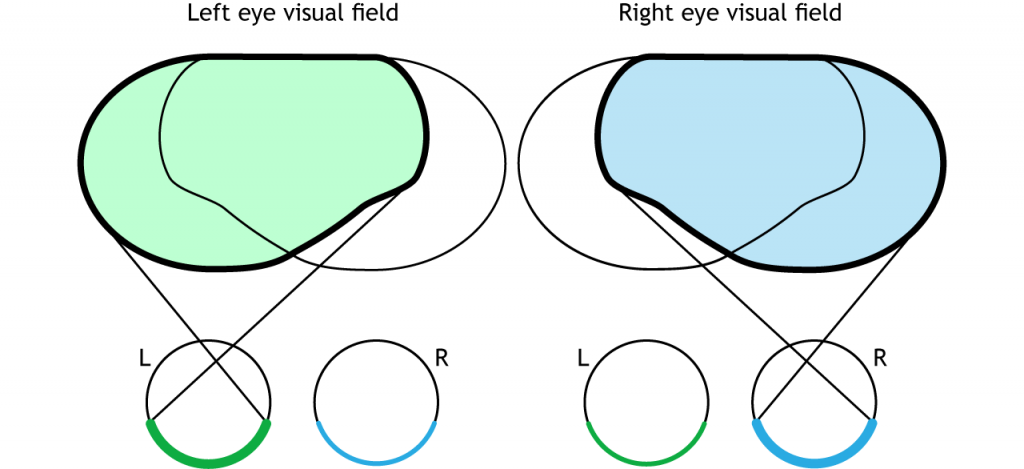

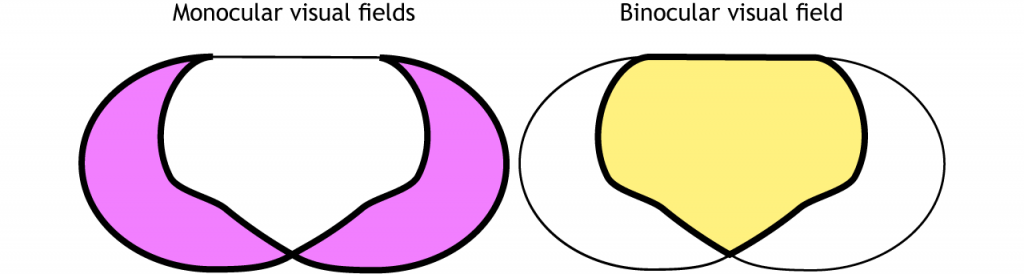

The full visual field can be divided in a few ways. Each individual eye is capable of seeing a portion of, but not the entire, visual field.

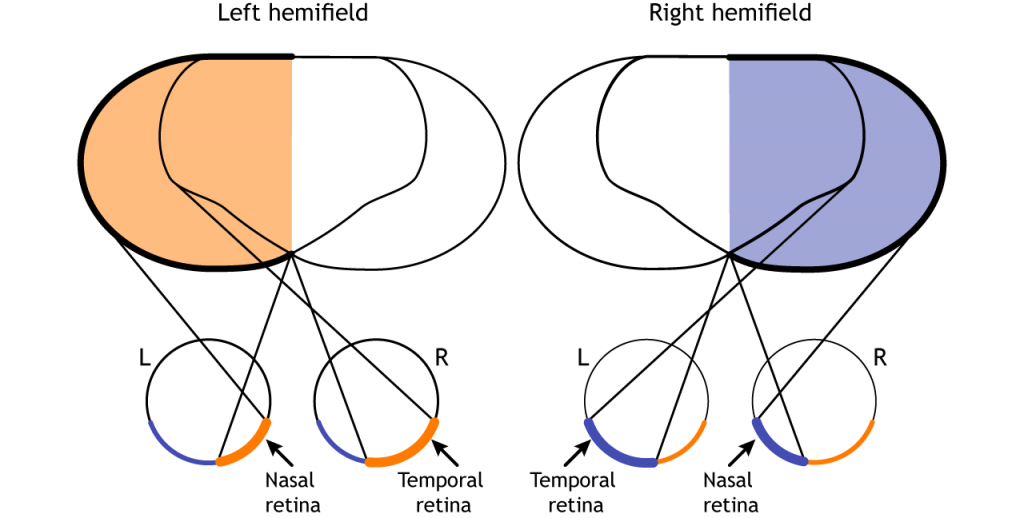

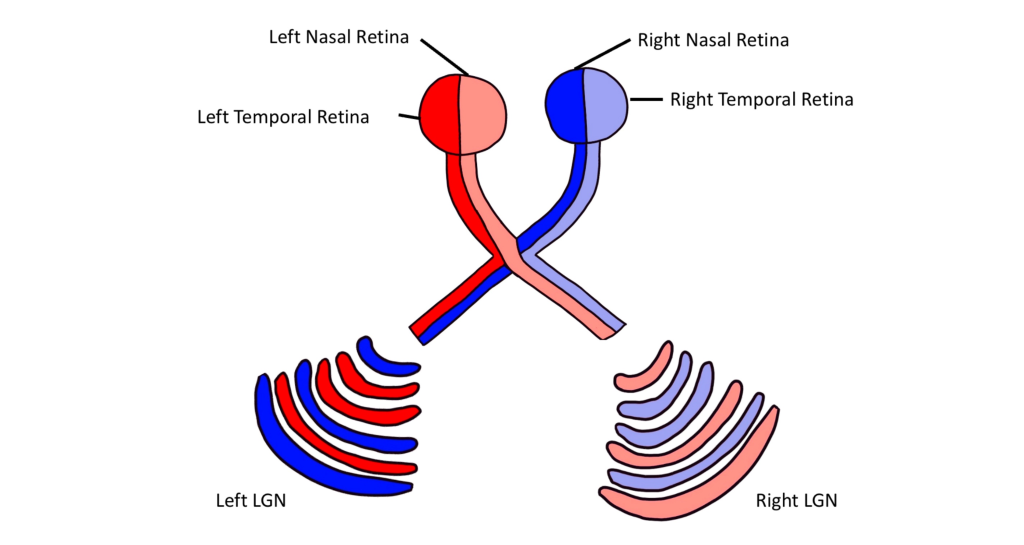

The full visual field can also be divided into the right and left hemifields. The hemifields range from the most peripheral point to the center point, splitting the full visual field into two equal regions. Both eyes are involved in viewing each hemifield. The fovea separates the retina into two sections: the nasal retina and the temporal retina. The nasal retina is the medial portion that is located toward the nose. The temporal retina is the lateral portion that is located toward the temples and temporal lobe. The nasal retina from one eye along with the temporal retina from the other eye are able to view an entire hemifield.

Finally, the full visual field can be separated into monocular and binocular regions. Each monocular field is visual space that can only be viewed by one eye. The binocular region is visual space that can be viewed by both eyes.

Pathway to Brain

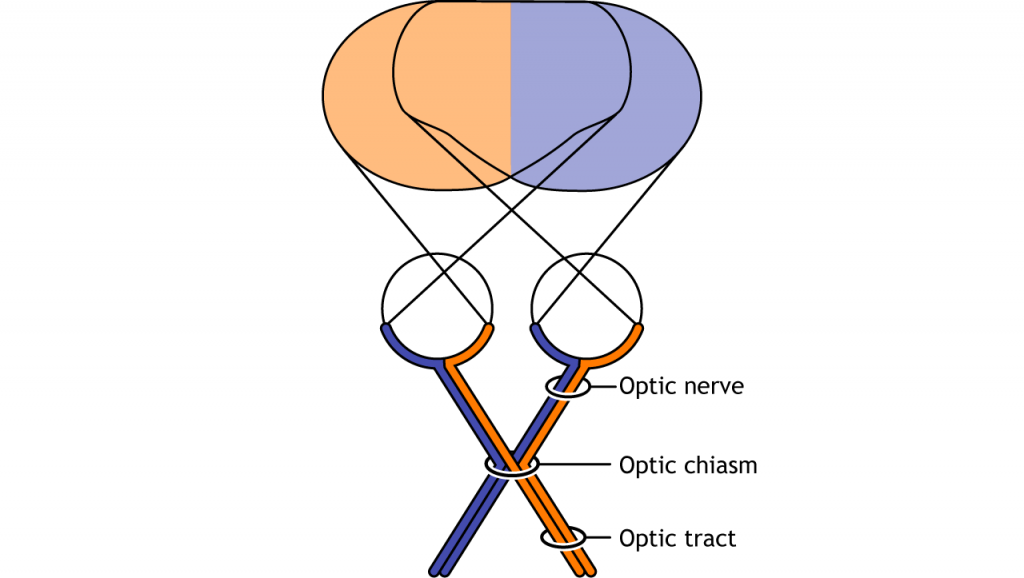

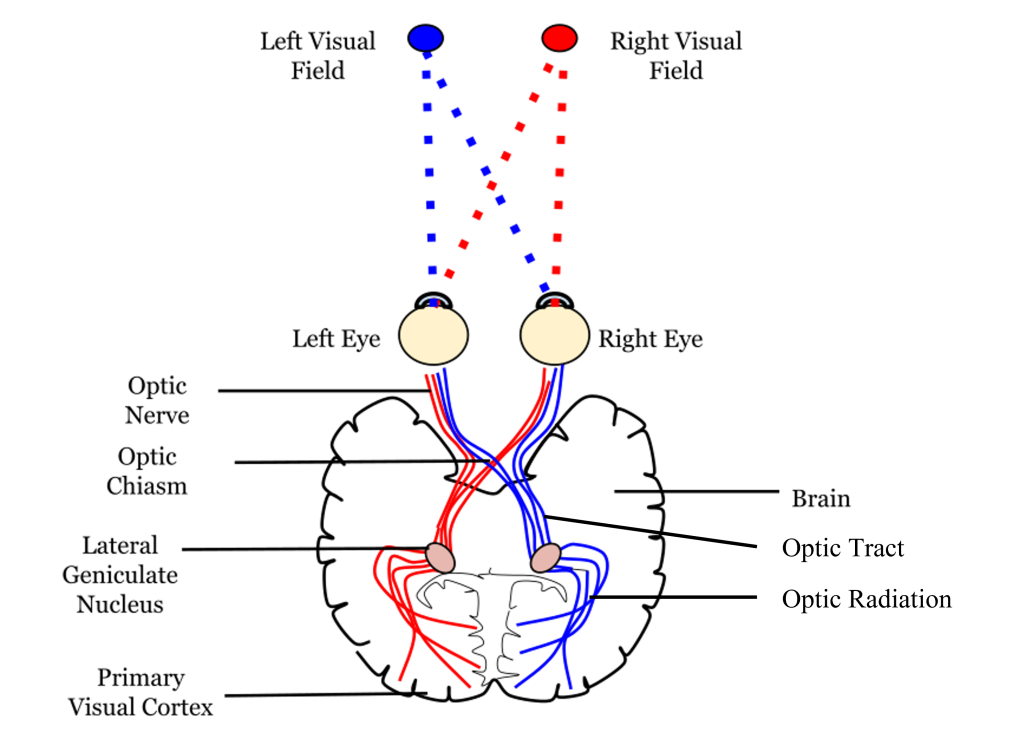

Visual information from each eye leaves the retina via the ganglion cell axons at the optic disc, creating the optic nerve. The optic nerve, or cranial nerve II, exits the posterior end of the eyeball, and travels posteriorly along the ventral surface of the brain. Like all other cranial nerves, the optic nerve is paired, meaning there is one for each eye. Both optic nerves merge at a spot called the optic chiasm, then diverge yet again as they travel posteriorly towards the thalamus.

The axonal connections in the optic nerve are not quite as simple as its anatomical appearance. From each optic nerve, some of the nerve fibers cross the midline (decussate), headed towards the contralateral hemisphere. Other nerve fibers meet at the optic chiasm, but then project into the ipsilateral hemisphere.

Prior to entering the brain, axons from the nasal portion of each retina cross the midline at the optic chiasm but the temporal portion of each retina does not cross at the optic chiasm.

View the optic nerve (cranial nerve II) using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

Since the axons from the nasal retina cross to the opposite side of the nervous system but the temporal retina axons do not, this leads to the brain processing input from the contralateral (opposite side) visual hemifield. Therefore, the right side of the brain receives visual information from the left hemifield and vice versa. The easy way to keep track of this unusual system is to remember that all information from the left visual field enters the right hemisphere of the brain, while visual information from the right visual field enters the left hemisphere of the brain.

Pathways from the Retina

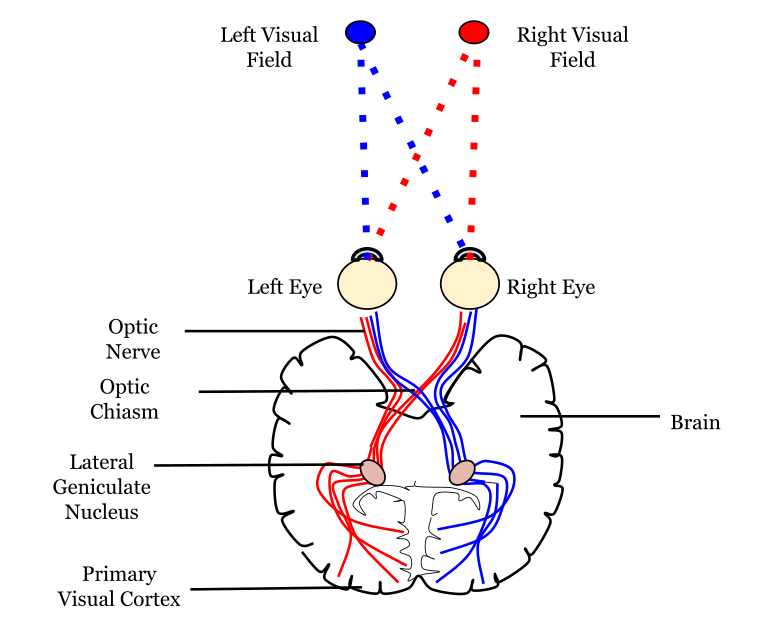

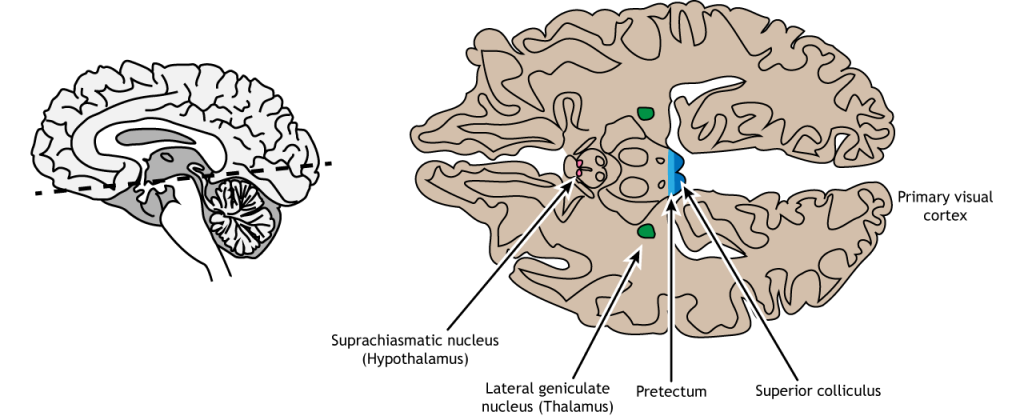

The retinal ganglion cells that exit the retina and project into the brain can take different paths. The retinofugal projection (fugal means “to flee”) is one of the major projection paths of the retinal ganglion cells. Most retinal output projects to the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus and then to the primary visual cortex, however there are subsets of cells that are routed through other non-thalamic pathways.

Non-Thalamic Pathways

Not all of the axons convey direct visual information into the thalamus for visual perception. Some ganglion cells project to the superior colliculus, a midbrain region via the retinotectal pathway (recall that the superior colliculus is a structure of the tectum). This pathway communicates with motor nuclei and is responsible for pupillary control. Specifically, it is responsible for movements that will orient the head and eyes toward an object to focus the object in the center of the visual field, the region of highest visual acuity.

A subset of specialized retinal ganglion cells project to the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the hypothalamus through the retinohypothalamic tract (starts in the retina, ends in the hypothalamus). It does not carry any conscious visual information. The retinohypothalamic tract conducts light information from a small group of intrinsically-photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. This structure functions to help the body adapt its sleep-wake cycle in the face of changing day-night patterns This region is critical for circadian rhythms and the sleep/wake cycle.

View the hypothalamus using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

View the midbrain using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

Thalamic Pathway: Lateral Geniculate Nucleus

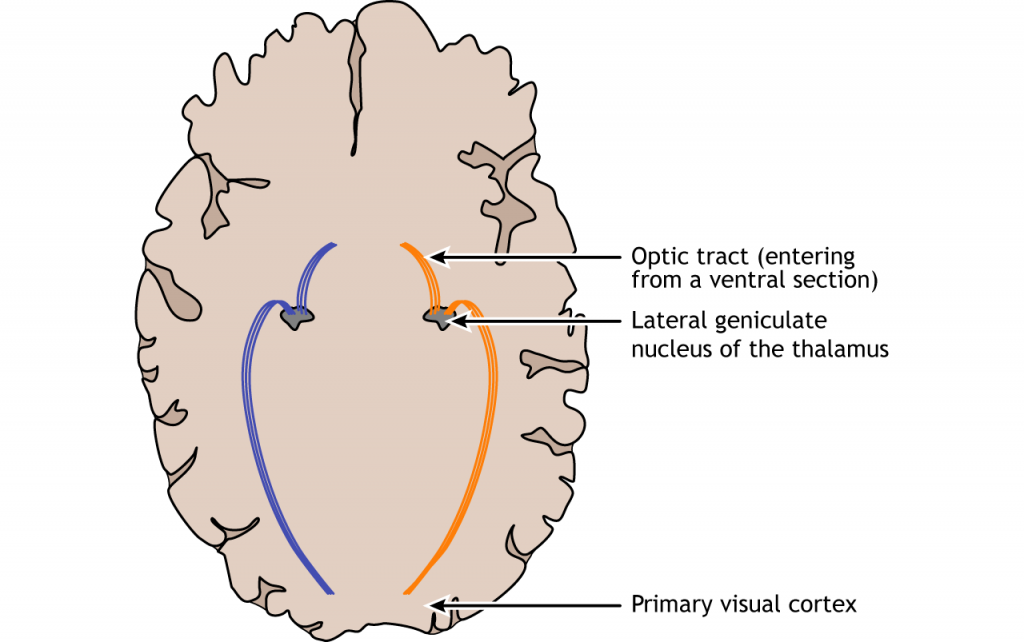

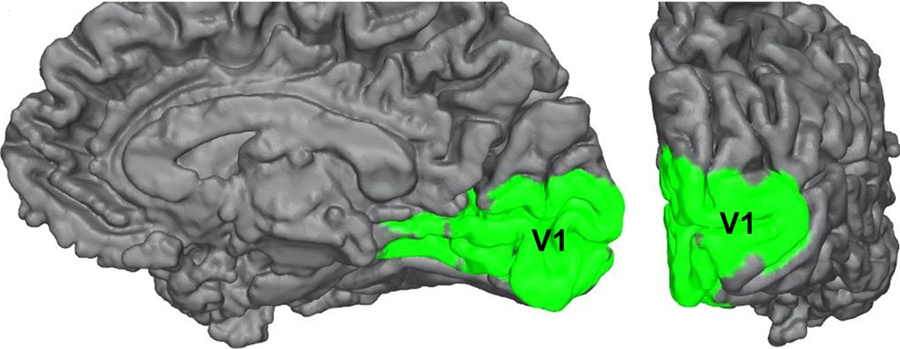

In conscious visual perception, the first synapse of the optic nerve is formed in the thalamus at a subregion called the lateral geniculate nucleus, or LGN. The optic tract enters the brain and ascends to synapse in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus. From there, axons project to the primary visual cortex, also called the striate cortex or V1, located in the occipital lobe.

Lateral Geniculate Nucleus

The lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus (LGN) has six distinct layers when examined in cross section. The LGN serves as the first synaptic site of the retinal ganglion cells that exited the retina.

Importantly, visual information is separated at the level of the LGN such that visual information from each visual field is all processed in the contralateral LGN. This means that information from the left visual hemifield, collected via the right temporal retina and the left nasal retina will all be processed within the right LGN. Information from the right visual hemifield, collected via the left temporal retina and the right nasal retina will all be processed by the left LGN.

Within the LGN, input coming from each eye is kept separate by the layers of the LGN. For example, notice that half of the layers of the right LGN process information from the right eye and the other half of the layers process information from the left eye.

The outputs of the LGN are a series of axonal bundles called the optic radiations. From the LGN of the thalamus, the optic radiations project to the occipital lobe at the caudal (posterior) end of the brain. Once visual information travels into the cortex, the process is less about sensation and mostly about perception.

View the thalamus using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

Striate Cortex (Primary Visual Cortex)

The outputs of the LGN are axons which form synapses in the primary visual cortex, which is also called V1 or the striate cortex. ‘Striate’ means ‘stripe’ and is named due to the presence of a large white stripe that can be seen in unstained tissue during surgical dissection. This white stripe is the bundle of incoming optic tract axons, which are heavily myelinated.

Each neuron in V1 receives visual information from a specific patch of retinal cells. This organizational pattern, where a section of retinal inputs map onto neurons of a specific section of V1, is called retinotopic organization. This retinotopic organization is conserved from the retina to the LGN, and finally to the primary visual cortex. Visual information from the fovea, despite being only 1% of the total visual field, takes up about half of all neurons in V1. After processing in V1, visual information is passed along to other cortical areas that contribute to various aspects of visual perception.

View the primary visual cortex using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

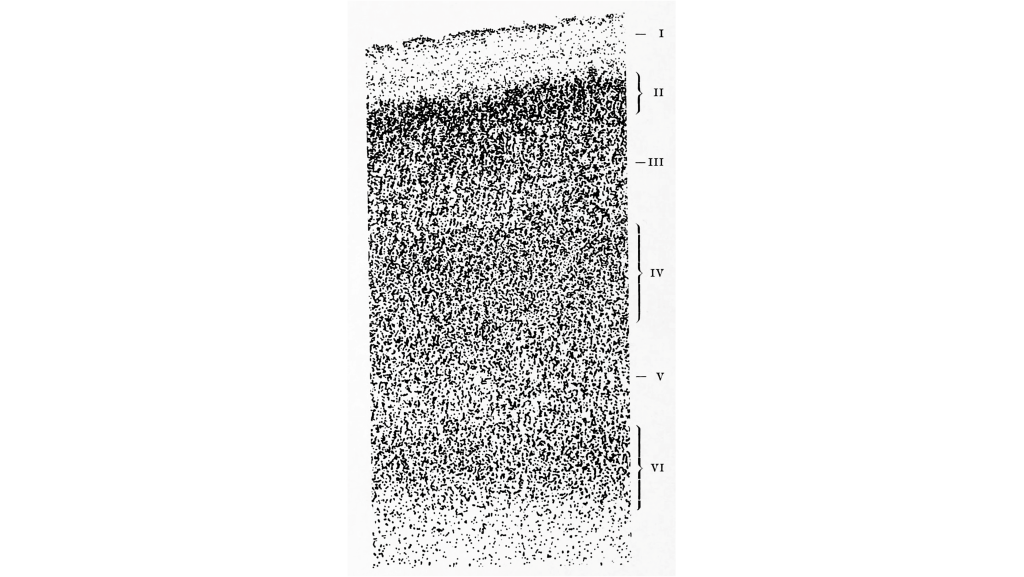

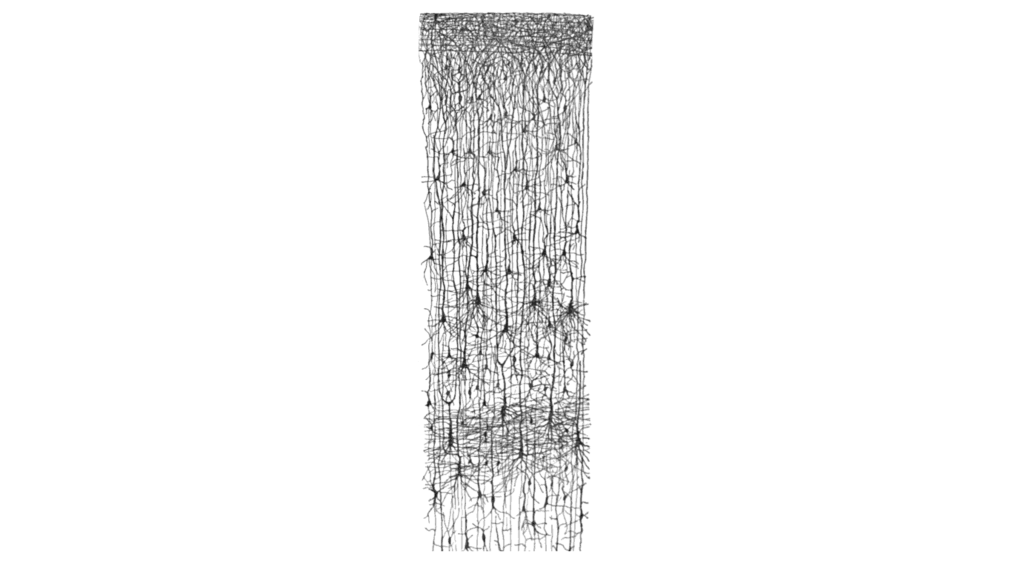

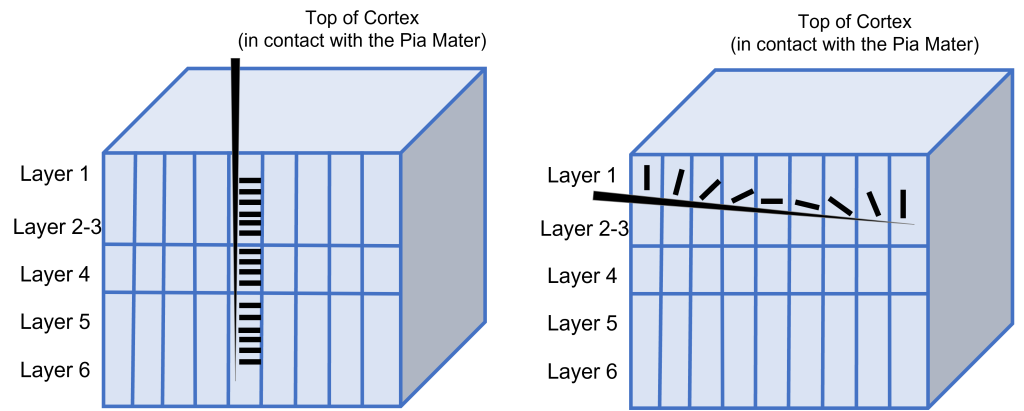

Cortical Layers

The cortex of the brain is arranged into six layers, named with the Roman numerals I-VI. The cells within these layers have different morphology. These cortical layers are especially visible within the striate cortex (V1). Within this region, the thickness of the cortex between the pia mater that is in contact with the top of the cortex and the white matter underlying the cortex is very thin (around 2 mm in thickness).

These cells within the six layers of the cortex are arranged in what are called ‘cortical columns’. This arrangement was discovered by Dr. Vernon Mountcastle in the 1950s. You can imagine that due to the directionality of communication in neurons, that information travels up and down the cells within a single cortical column.

Features of the Primary Visual Cortex: Contributions of David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel

Dr. David Hubel and Dr. Torsten Wiesel followed up on this critical discovery by Mountcastle to describe neuronal processing within the visual cortex. Their discoveries in this field led to them being awarded the Nobel Prize in the field of Physiology or Medicine in 1981. Highlighted below are some of their major contributions.

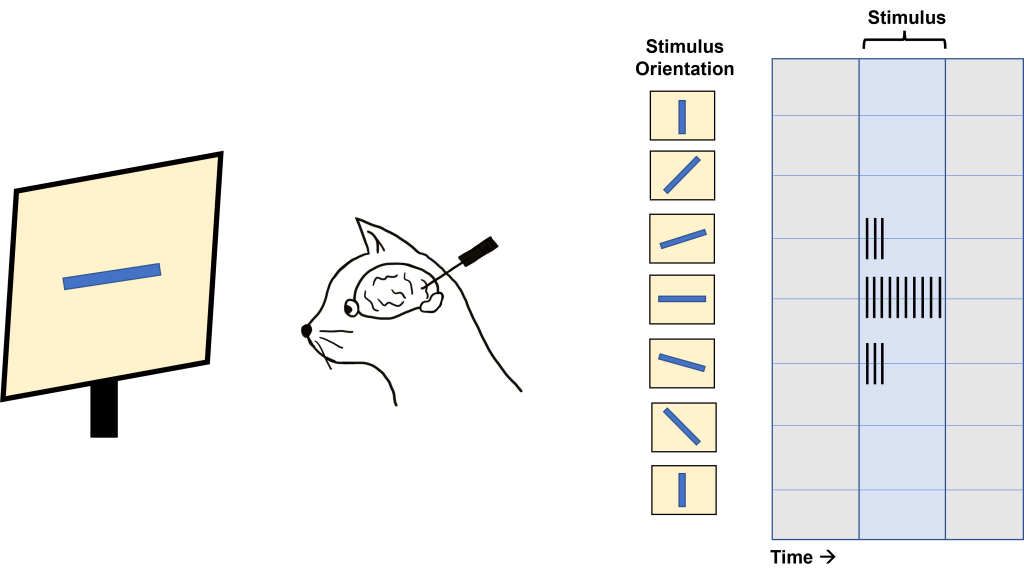

Orientation Selectivity

Hubel and Wiesel used microelectrodes to map the functioning of the visual cortex. In one of their famous experiments, Hubel and Wiesel used anesthetized cats to determine how the visual cortex processes visual information. During their experiment, they were showing the anesthetized cat different visual stimuli through the projection of slides with different images onto a screen while recording from neurons within the visual cortex. Due to when this experiment was done, these slides were large and plastic and had to be physically inserted into a projector. In the process of inserting these slides into the projector, a bar of light was projected onto the screen by the edge of the slide. Quite by surprise, the act of changing the slides (and the bar of light that resulted) caused the neurons within the cat brain to fire action potentials. Hubel and Wiesel determined that the stimulus causing the neurons to fire was the angle of the bar of light projected on the screen.

In fact, the neurons within the visual cortex responded best to a line in a specific orientation and the firing rate of the neuron increased as the line rotated toward the “preferred” orientation. The firing rate is highest when the line is in the exact preferred orientation and different orientations are preferred by different neurons. This discovery was due to some great luck for Hubel and Wiesel as they were recording from neurons that had a preferred orientation that exactly matched the angle of changing the slides in their projector!

This orientation selectivity within the visual cortex is the same for all neurons located within a single cortical column. This means that the cells in each cortical column will respond optimally to a line at a preferred orientation. So, if a recording electrode is inserted vertically through the cortex to record from cells within a single cortical column, all cells will respond optimally to the same sensory stimulus. If the recording electrode is inserted horizontally, such that it records across multiple cortical columns, each cortical column will respond optimally to a different sensory stimulus.

Ocular Dominance Columns

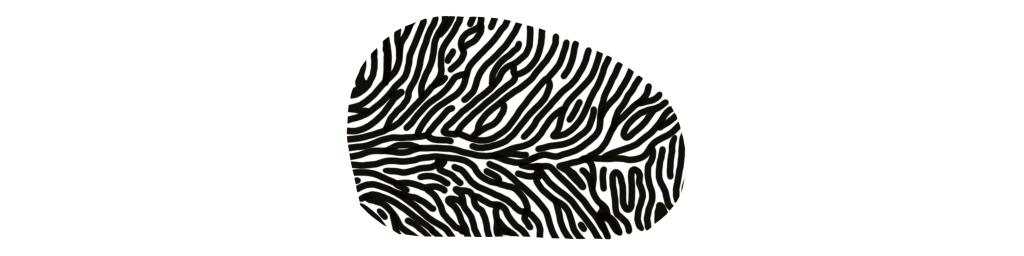

Another experiment by Hubel and Wiesel determined the existence of ocular dominance columns, or columns of neurons within the visual cortex that respond preferentially to either the left or right eye.

For this experiment, Hubel and Wiesel injected a radioactive amino acid into one of the eyes of a monkey. This amino acid then travels by anterograde transport through the retinal ganglion cells of the eye through the first synapse at the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus, and then through the next synapse with the striate cortex. Radioactivity within the striate cortex can then be visualized through the process of autoradiography.

In an autoradiograph image of the striate cortex, there are alternating areas that appear white in color with areas that appear black in color (similar to the stripes on a zebra). The areas of the cortex that appear white are the areas that took up the radioactive amino acid and are processing information from the injected eye. The areas of the cortex that appear black are areas that do not have the radioactive amino acid and are processing information from the eye that was not injected. Recall, that although information from the left visual hemifield is processed on the right side of the brain, the left visual hemifield information is collected from both eyes via the left nasal retina and right temporal retina. Therefore, both eyes are processed across both the left and right visual cortex.

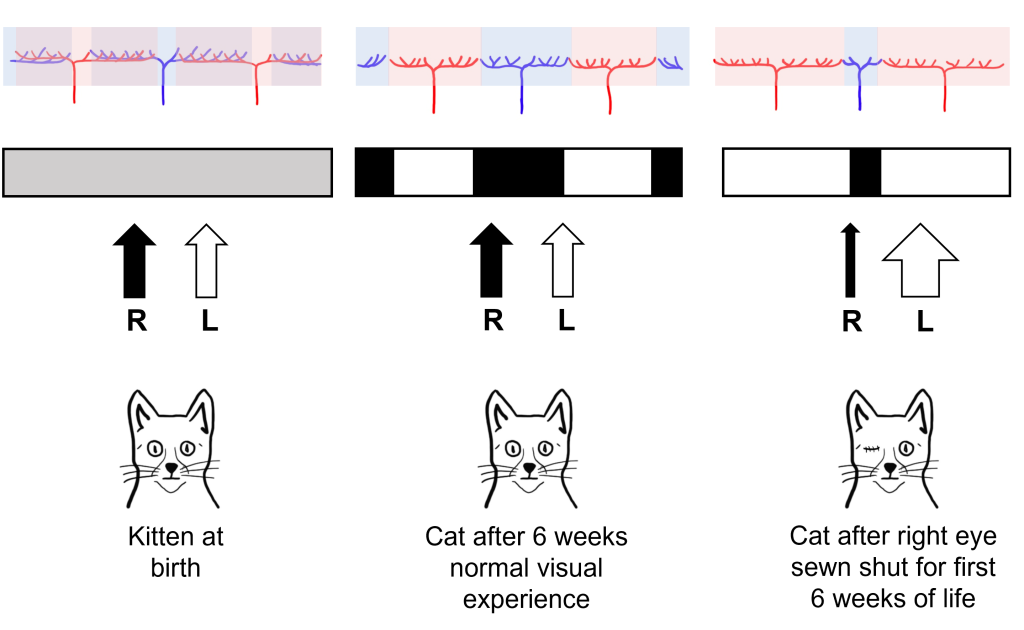

Interestingly, in newborn cats that had not had any visual experience, they did not observe the ocular dominance columns. Instead, they saw that the inputs of the left and right eye overlapped substantially within the visual cortex. Hubel and Wiesel were interested in understanding how these ocular dominance columns develop between infancy and adulthood and whether their development was dependent on visual experience.

For their experiment, they took a kitten immediately after birth, and sewed the right eye of the kitten closed, so that the eye could no longer have any visual experience, a condition called monocular deprivation (‘mono’ meaning ‘one’ and ‘ocular’ meaning ‘eye’). After this six-week period of monocular deprivation, the eye of the cat was reopened so that it could take in the visual environment. A control group of cats had normal visual experience for this same six-week period.

In control cats that did not experience monocular deprivation, Hubel and Wiesel found that they developed normal ocular dominance columns at six weeks post birth. The cats that experienced monocular deprivation for the first six weeks of life, however, showed abnormal development of the ocular dominance columns. The columns that normally served the right eye (that was sewn shut) shrank in size, and the neighboring columns that served the left eye grew into the unoccupied cortical space. Hubel and Wiesel were able to conclude that visual experience was necessary for the ocular dominance columns to develop. In fact, they found that there was a critical period in cat visual development in the first six weeks of life where visual experience is required for normal visual development.

Importantly, these structural changes also translated into functional changes for the vision of the cat. Cats that experienced monocular deprivation had decreased visual function in the eye that was sewn shut for the rest of the cat’s life. Even though the sewn shut eye was reopened after the critical period, the development of the ocular dominance columns in the brain was already complete and thus the brain could never process visual information from the sewn shut eye.

Higher-Level Processing of Sensory Information

Sensory system processing of input does not end upon reaching the primary sensory cortex in any sensory system. Information typically gets sent from the primary sensory cortex to other sensory association regions throughout the brain. The characteristics of sensory information becomes more complex as this higher-level processing occurs.

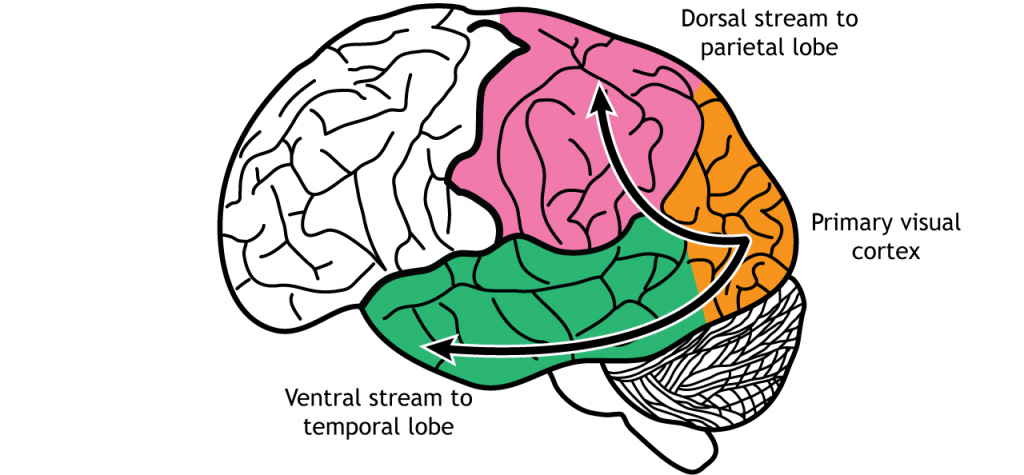

Post-Striatal Processing

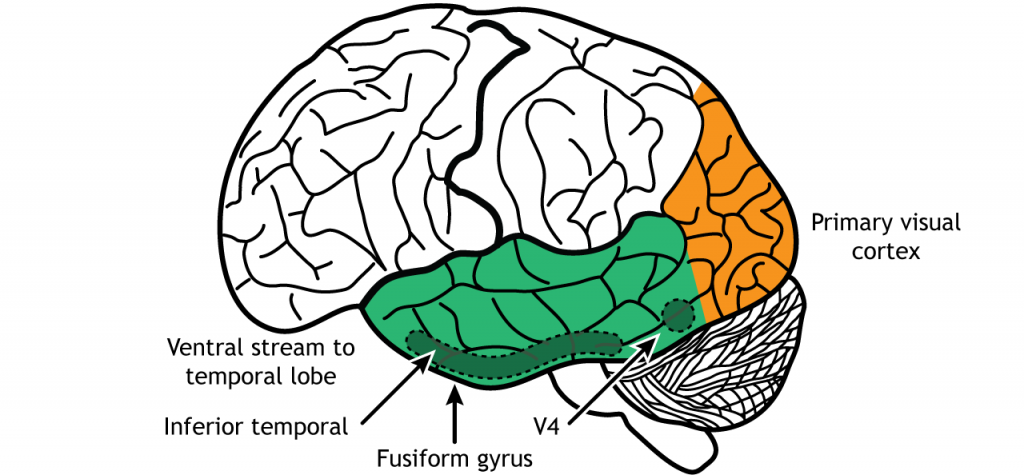

In the visual system, there are two broad streams of information that leave the striate cortex. Visual information passes through two streams of communication: the dorsal stream and the ventral stream. In the ventral stream, information travels from the primary visual cortex down through the inferior temporal lobe is responsible for determining object recognition, or what an object is. Differentiating between an apple and a person occurs in this stream. In the dorsal stream, information travels from the striate cortex up through the parietal lobe and is responsible for motion or spatial components of vision.

Dorsal Stream

The dorsal stream is described as the “where” pathway because these structures help us identify where objects are located in the space around us. One of the most important regions in the dorsal pathway is region MT, also called V5, which contributes to perception of motion. In this region, neurons are preferentially activated by a specific direction of movement by an object – for example, left to right or up to down. As an example, remember the receptive fields in the primary visual cortex were activated by lines at a specific orientation. Like that, in V5, the neurons would be activated by lines moving in a specific direction.

As information continues to be processed through the dorsal stream, the neurons become selective for more complex motions. The dorsal stream is also important for processing our actions in response to visual stimulation, for example, reaching for an object in the visual field or navigating around objects while walking.

These structures also guide us when we move through our environments, contributing to our sense of spatial awareness. For example, a task such as reaching out to grab an object in front of you uses a combination of these features, so this task is guided largely by dorsal stream structures.

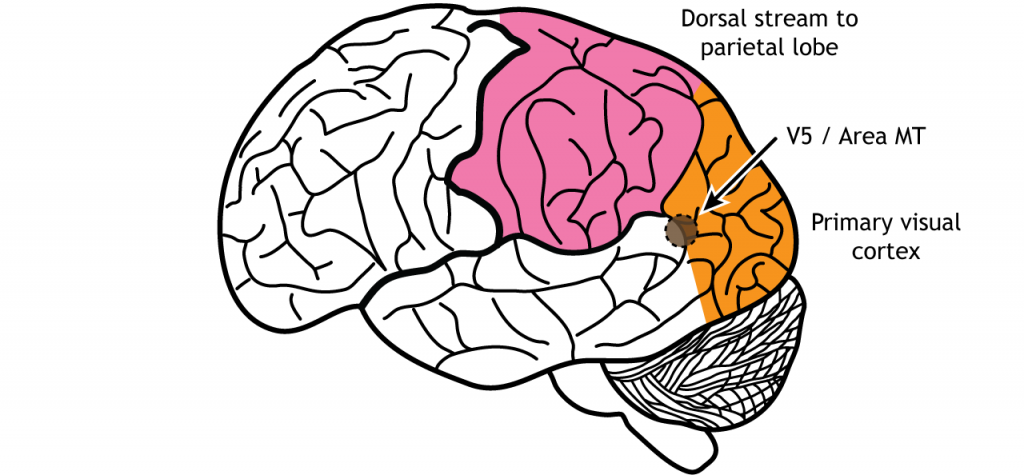

Figure 30.20. Area MT, also called V5, is an early processing region of the dorsal stream through the parietal lobe. Neurons in the region are activated by direction of an object in a specific direction. ‘Area MT’ by Casey Henley is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share-Alike (CC BY-NC-SA) 4.0 International License.

Ventral Stream

The ventral stream is the “what” pathway, and helps in the identification of objects that we see. Object identification is a key function of our visual system. The ventral visual stream is responsible for this process. Further, ventral stream structures are important for visual memory. Like the more complex activation characteristics of region MT in the dorsal stream, neurons in Area V4 in the ventral stream show more complex receptive fields and show sensitivity to shape and color identification. In fact, there is a rare clinical condition in humans called achromatopsia, in which individuals have partial or complete loss of color vision. These individuals still have normal functioning cones within the retina, and normal LGN and primary visual cortex function. Instead, they typically have damage to occipital and temporal lobes, where the ventral stream is located.

A major output of area V4 is area IT, located within the inferior temporal lobe. As information travels to area IT it continues to be processed and differentiation of objects occurs. Neurons located in area IT are important in learning and memory in visual perception (have I seen that before?), and have been found to respond to colors and shapes.

Another region within the ventral stream called the fusiform face area, located in the fusiform gyrus, which lies on the ventral aspect of the temporal lobe, contains neurons that are activated by faces and can be specialized to one specific face. When the visual system senses these complex stimuli, those signals get processed through these ventral stream pathways. These incoming stimuli are compared with the memories stored in the ventral stream, and this comparison contributes to our capacity for perception and identification.

The two streams are not independent of each other. Rather, successful organisms require the melding of both components of visual perception. For example, imagine you are a prehistoric organism living in a food-scarce environment. Approaching a small berry tree, you would use ventral stream structures to correlate the berries with memories: Did these berries taste good and give me the calories I need to survive? Or did these berries make me violently ill, and are therefore probably poisonous? If they are the delicious berries that I want, I will use the dorsal stream structures to take note of their precise location so I can reach out for them and pick the berries . In this example, proper interaction of the dual streams contributes to goal-driven actions.

The inferior temporal lobe also makes reciprocal connections with the structures in the limbic system. The limbic system plays an important role in processing emotions and memory, both of which are significant components to visual perception. The amygdala ties visual stimuli with emotions and provides value to objects. A family member will have emotional ties that a stranger will not. The hippocampus is responsible for learning and memory and helps establish memories of visual stimuli.

View the amygdala using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

View the hippocampus using the BrainFacts.org 3D Brain

Key Takeaways

- The nasal and temporal retinal regions are responsible for viewing specific regions of the visual field

- Some retinal projections cross the midline at the optic chiasm, causing the left side of the brain to process the right visual hemifield and vice versa

- The retinal axons synapse in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus. Information then travels to the primary visual cortex

- Receptive fields and the preferred visual stimuli for neuron activation become more complex as information moves through the visual pathway

- Primary visual cortex neurons have linear receptive fields are are activated by a line in a specific orientation

- Area MT / V5 is activated by motion in a specific direction

- Area V4 is activated by specific shapes and colors

- The fusiform gyrus is activated by faces

- The retina also projects to midbrain regions

- Ocular dominance columns that process information from either the left or right eye develop during a critical period of development

Test Yourself!

Attributions

Portions of this chapter were remixed and revised from the following sources:

- Foundations of Neuroscience by Casey Henley. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

- Open Neuroscience Initiative by Austin Lim. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Our nervous system is equipped with a variety of specialized biological “tools” that can detect much more than just photons of light. We can detect the shape of air waves, and interpreting those signals give us sound information and the perception of music. In this chapter we will trace how sounds travel through the structures of the ear, ultimately causing the auditory receptors to alter their activity and send their signals to the brain.

Properties of Sound

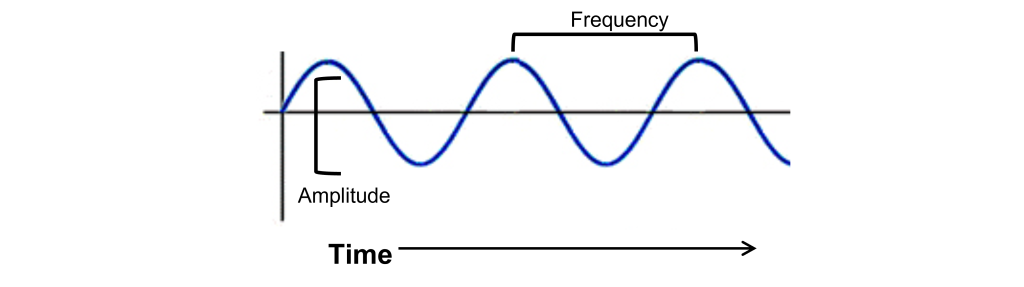

Unlike photons of light, sound waves are compressions and rarefactions of a medium. For us land animals, that medium is usually air, but sound waves can propagate very well in water or through solids. Before we get to the anatomical structures involved in sound perception, it is important to first understand the physical nature of sound waves. All sounds, from the clattering of a dropped metal pan to the melodies of a Mozart violin concerto, are contained in their corresponding sound waves. Two components of sound waves are frequency and amplitude.

- Frequency, or “How often do the sound waves compress?” The greater the frequency, the higher the pitch. The highest notes humans are able to hear is around 20,000 Hz, a painfully-shrill sound for those who can hear it. People often tend to lose their high frequency hearing as they age. On the opposite end of the spectrum, low frequency sounds are the deep rumbles of bass, and the human ear can hear sounds down in the 20 Hz range.

- Amplitude, or “How much do the waves displace the medium from baseline?” The larger the amplitude of the wave, or the greater distance between the peak and the trough of the signal, the louder the sound is. Loudness is measured in decibels (dB). To give you an idea of approximate sound intensities, the background noise of a quiet library is about 40 dB, and a typical conversation is close to 60 dB. A rock concert or lawnmower is between 100 and 110 dB, which is right around the pain threshold. Prolonged exposure to these high amplitude sound waves can lead to permanent damage to the auditory system resulting in hearing loss or tinnitus (a ringing in the ear, even in the absence of a sound stimulus).

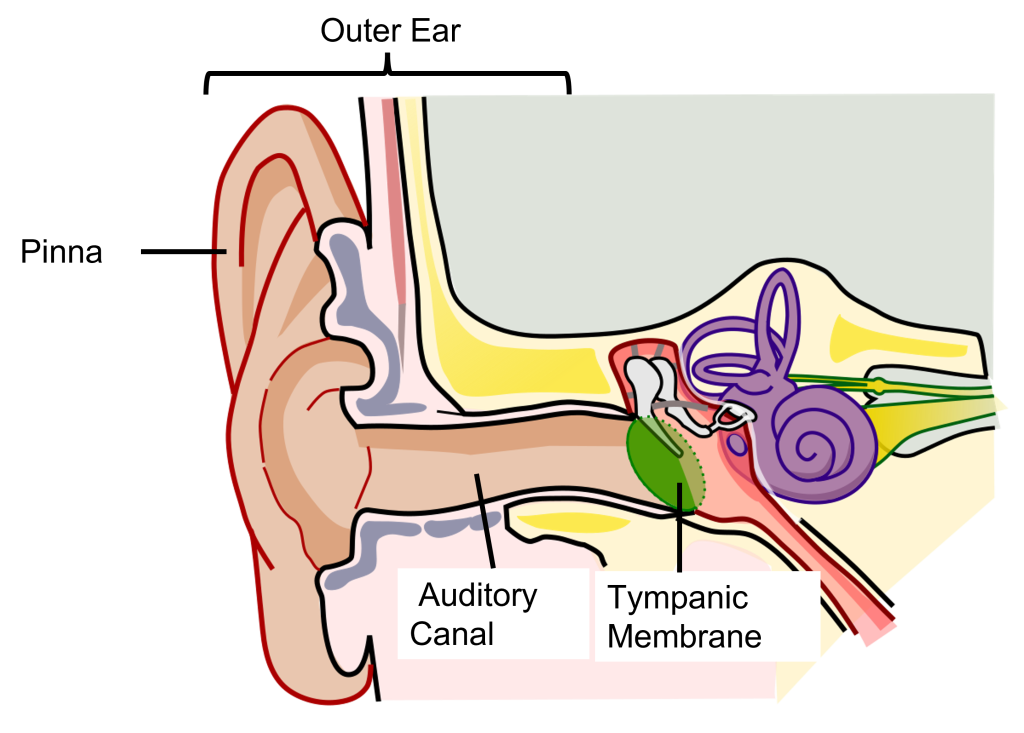

Physical Structures of the Auditory System: Outer Ear

Our auditory system is a series of physical structures and nervous system components that are responsible for conveying sound waves into meaning and context.

The external component of the auditory system begins with the pinna. Its shape functions as a funnel, capturing and channeling sound waves into the auditory canal. The pinna and the auditory canal are parts of the outer ear. Also, because the pinna is asymmetrical, its shape helps us determine where a sound is coming from. In some nonhumans, the pinna serves these functions and more. For instance, some animals are able to disperse excess heat through their ears (elephants), and some even use them to display emotion (dogs, horses).

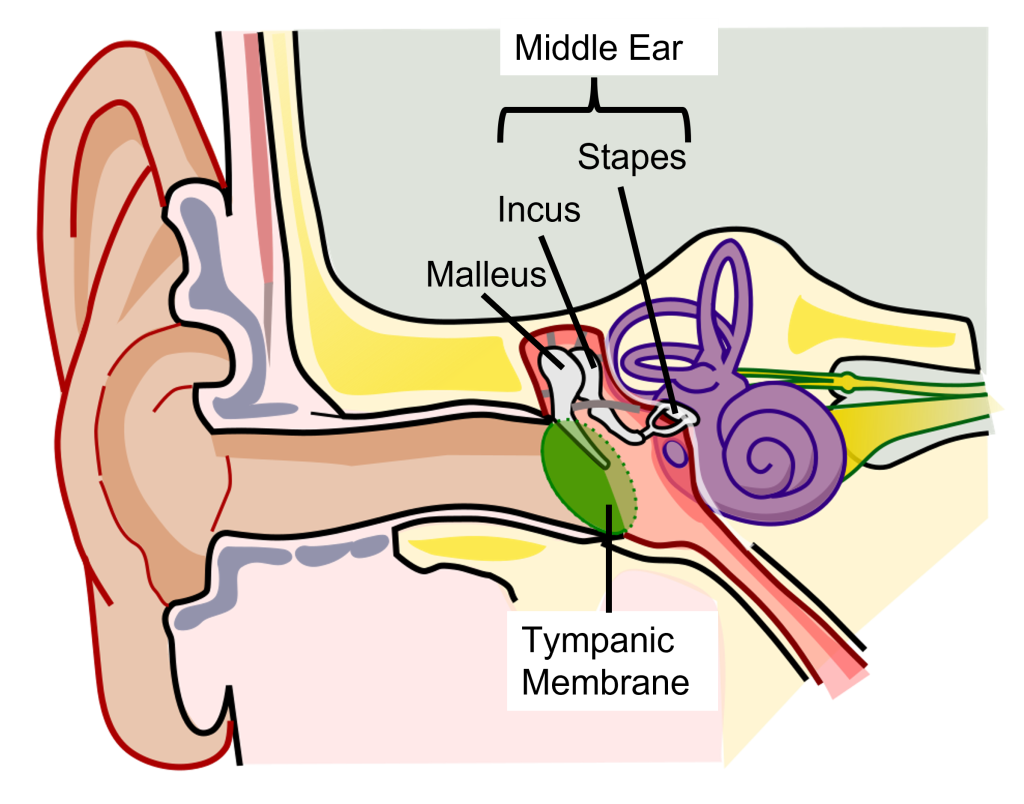

At the end of the auditory canal is the tympanic membrane, or ear drum. This membrane is a very delicate piece of tissue at only 0.1 mm thin and is subject to damage by physical injury such as head trauma, nearby explosions, or even changes in air pressure during scuba diving. When incoming sound waves reach the tympanic membrane, it vibrates at a matching frequency, and amplitude. The tympanic membrane also represents the boundary between the outer ear and the middle ear.

Physical Structures of the Auditory System: Middle Ear

The middle ear is an air-filled chamber. Physically attached to the tympanic membrane are the ossicles, a series of three bones that convey that vibrational sound information. These bones in order, called the malleus, incus, and stapes, conduct vibrations of the tympanic membrane through the air-filled middle ear. The stapes has a footplate that attaches to a structure called the oval window, which serves as the junction between the middle ear and the inner ear. The middle ear serves important functions in both sound amplification and sound attenuation.

Sound Amplification

The tympanic membrane and the ossicles function to amplify incoming sounds, generally by a tenfold difference. This amplification is accomplished through 2 mechanisms:

- Due to the ossicles being connected, the ossicles act in a lever-like fashion to amplify the movements of the tympanic membrane to the oval window

- The stapes has a smaller area on the oval window than the tympanic membrane, thus movements of the larger tympanic membrane must be transformed into smaller and stronger vibrations at the oval window.

This amplification is important because the inner ear is filled with liquid rather than air, and sound waves do not travel very well when moving from air into a denser medium - think about how muffled sounds are when you submerge your head underwater.

Sound Attenuation

The movement of the ossicles are partially regulated by two different muscles, the tensor tympani muscle which connects with the malleus, and the stapedius muscle which connects to the stapes. When these muscles contract, it causes the ossicles to be more rigid and for the ossicles to move less, which decreases the intensity of loud sounds. This response, called the acoustic reflex, dampens incoming sound by about 15 dB. (This is why we talk much louder than normal when we first leave a concert: we have lessened auditory feedback from our ears, so we tend to talk louder to compensate.) The muscles contract at the onset of loud noises with a slight delay of 50-100ms.

Physical Structures of the Auditory System: Inner Ear

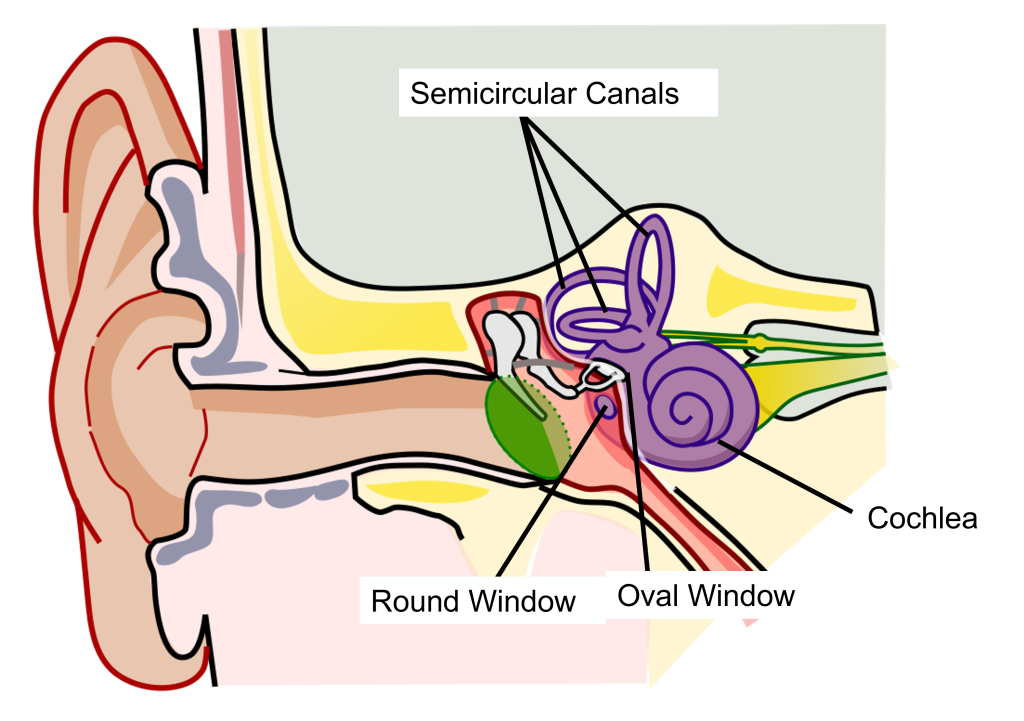

The inner ear is a fluid-filled structure made up of two structures: the cochlea that functions in hearing, and the semicircular canals that function in balance.

The auditory part of this structure is a small spiral-shaped structure about the size of a pea, called the cochlea (cochlea is named for the Ancient Greek word “snail shell”.) The cochlea has two small holes at its base: the oval window and the round window.

Cross Section of the Cochlea

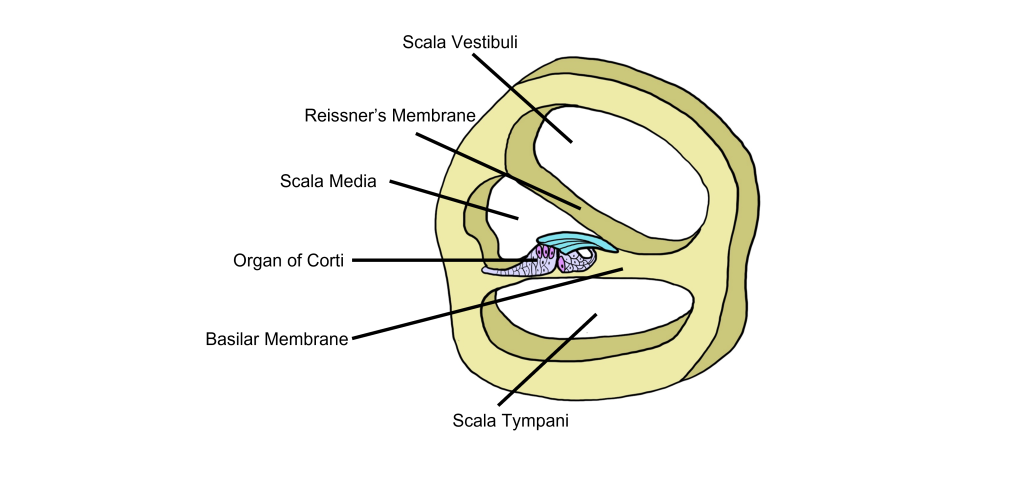

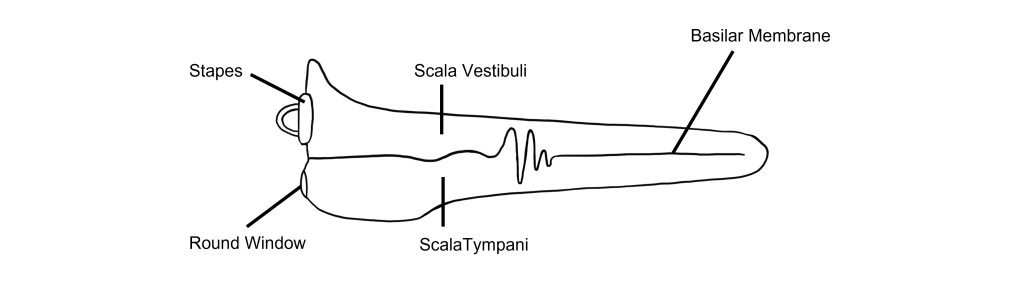

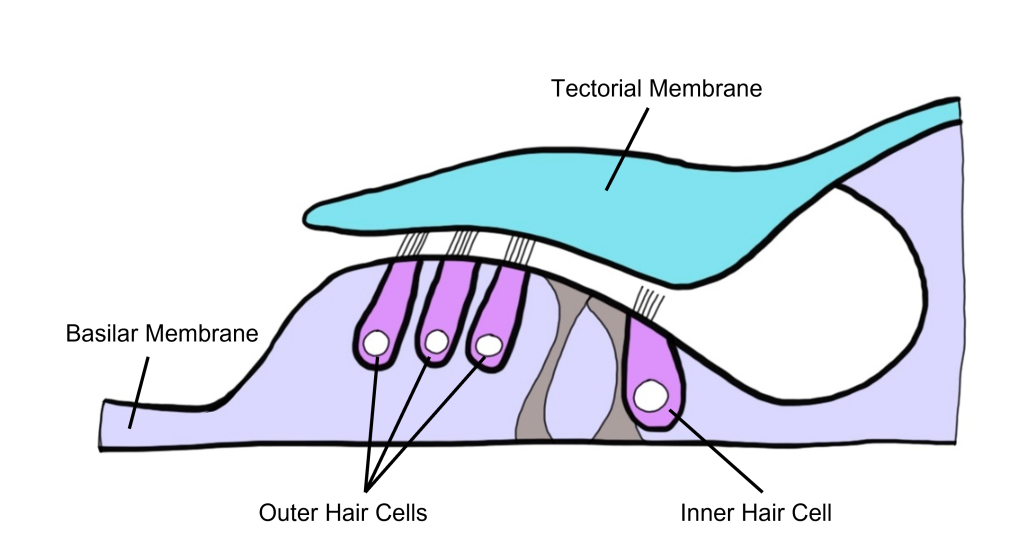

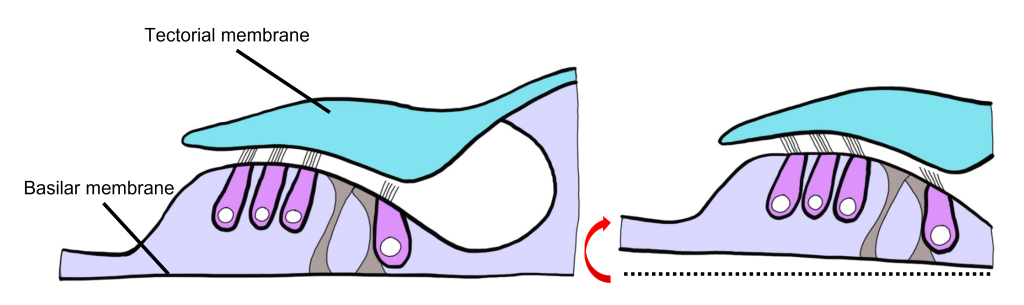

When we examine a cross-section of the cochlea, we can see that there are 3 distinct fluid-filled chambers called the scala vestibuli, the scala media, and the scala tympani. These chambers are separated from each other by membranes.

The fluid found within the scala vestibuli and scala tympani is called perilymph and it has a low concentration of potassium and a high concentration of sodium. The scala media is filled with a fluid called endolymph that has a high concentration of potassium and a low concentration of sodium.

Reissner’s membrane separates the scala vestibuli from the scala media. The basilar membrane separates the scala tympani from the scala media.

Basilar Membrane

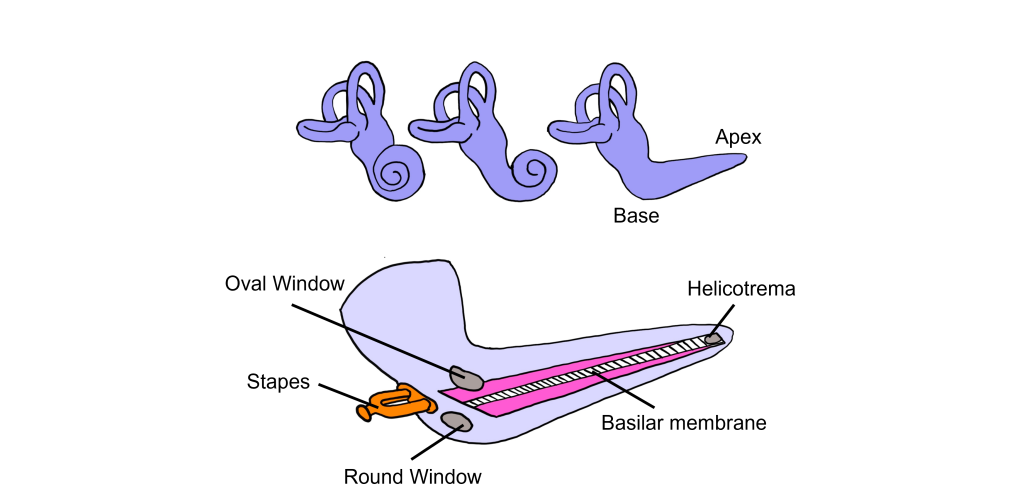

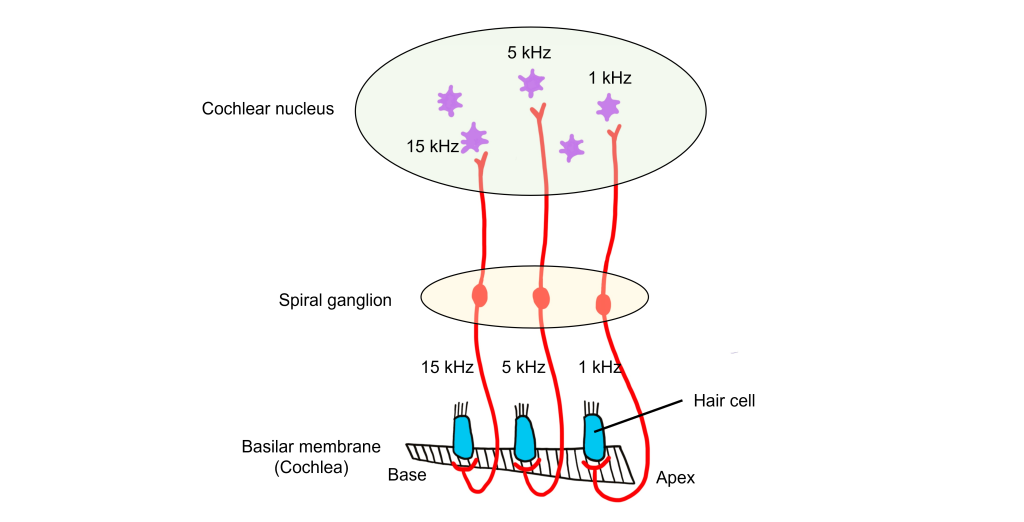

Think of the cochlea as a rolled-up cone. If this cone was theoretically unrolled, the widest diameter portion, called the base, would be closest to the oval window, while the narrowest portion, called the apex, would be at the center of the spiral.

The basilar membrane runs down the middle of the cochlea. The width of the basilar membrane changes as it runs down the length of the cochlea from the base to the apex. This change in shape from the base to the apex is important: objects with different stiffness vibrate at different frequencies. The base of the cochlea is stiff and rigid and will vibrate at high frequencies. Whereas the apex is wider and less stiff, so it vibrates at lower frequencies.

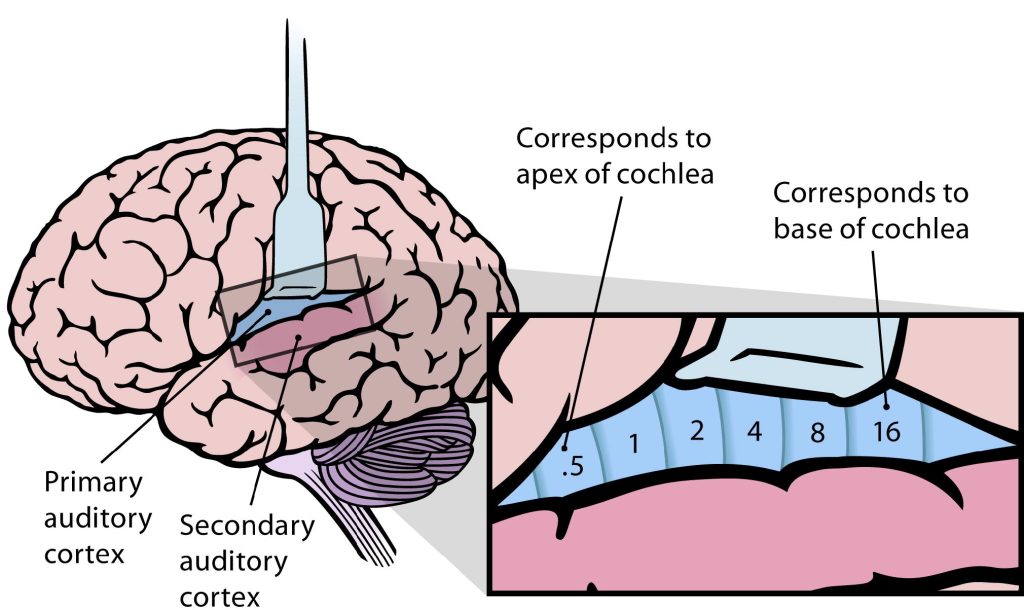

Because different frequencies of sound affect different areas of the basilar membrane, the basilar membrane is what is referred to as tonotopically organized. In fact, you can think about the way that frequencies are mapped to the basilar membrane similar to a backwards piano.

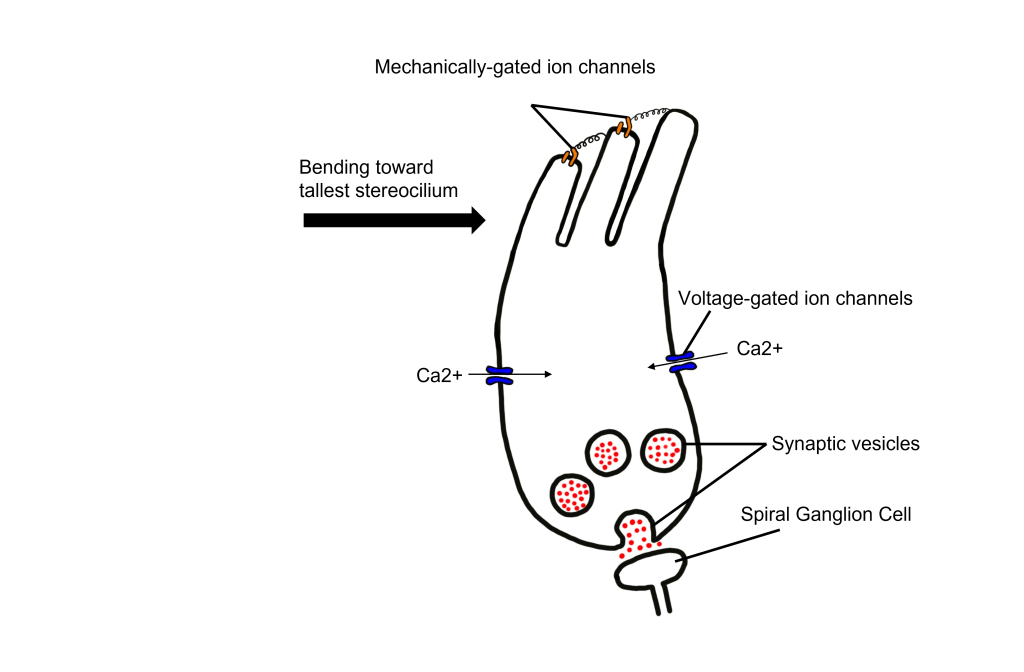

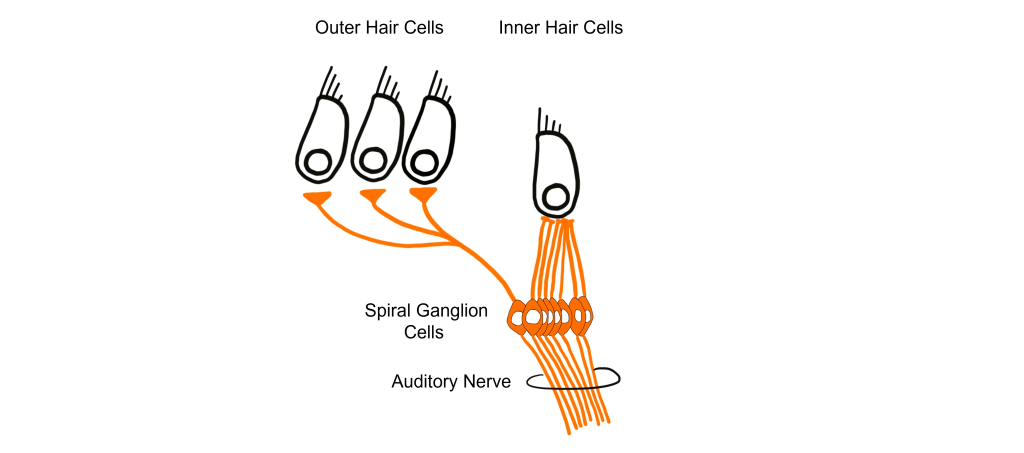

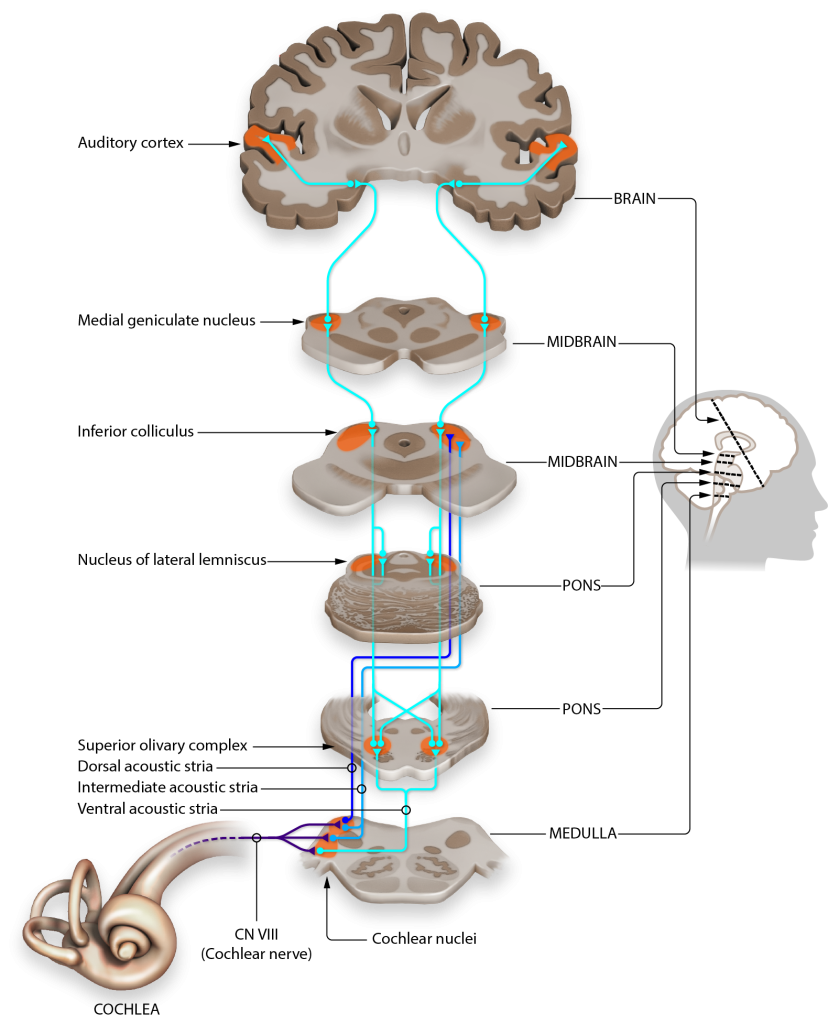

Let’s consider how sounds will affect the cochlea. For simplicity's sake, the figure here shows only the scala vestibuli and the scala tympani (not the scala media) with the basilar membrane running down the middle. Keep in mind that due to the flexibility of Reissner’s membrane that separates the scala vestibuli from the scala media, we can assume that pressure changes in the scala vestibuli are transferred through the scala media, ultimately affecting the basilar membrane.