7 The Resting Membrane Potential – when resting isn’t restful

Learning Objectives

- Become familiar with the concepts of voltage, current, and resistance (conductance), Ohm’s law

- Be able to use the Nernst potential to calculate equilibrium potentials.

- Be able to use the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation to calculate membrane potential in a realistic cell.

- Appreciate the function of the Na+/K+ pump (ATPase)

All cells in all organisms, from bacteria to Bach, contain a membrane potential. That is, there is a voltage difference between the inside and outside of the cell. It is not a huge voltage, but it is not inconsequential either. The voltage across the cell membrane of animal cells is a little less than 0.1 Volt, across bacteria it is twice that and plant cells have voltages that may reach 0.3 V. Like I said, not a lot of voltage, but considering these are tiny things, it is substantial. If you stack up five plant cells, you could generate the same voltage found on the battery operating a flashlight. Although there are several ion channels and pumps responsible for the voltage across a cell membrane, most of the voltage that resides across a neuron or a muscle cell is due to a type of channel called a “leak” potassium channel. It is called a potassium channel because it is selective for potassium ions. It is called a “leak” channel because it is always open and in that way acts like a leak in the membrane to potassium. We will see why this leak creates a voltage, or potential, across the membrane shortly, but first we must make a brief digression into electricity.

A Short Digression: Electricity for Neurobiologists

If you already know something about electricity (other than not to stick your finger in an electrical outlet), that is good but it means you will have to pay extra close attention to this section. Your familiarity may cause you to gloss over some important features.

First, we must define some terms:

Charge. Charge is, well, charge. There are electrons, which are negative charges, and protons, which are positive charges. Most of the time we will be considering ions, which contain a surplus of electrons or protons. The important point is that charge is either positive or negative. The symbol used to describe charge is Q (not the Q that is revealing the cabal of liberal, child-eating democrats secretly ruling the country). The unit of charge is the coulomb. One coulomb is equal to the charge on 6.241 x 1018 protons. This is not a number you need to remember. I just mention it in case anyone is interested.

Current. Current refers to the movement of charge. It is symbolized by I and its unit is the ampere, A. One ampere is defined as the movement of one coulomb of charge per second.

Voltage. Voltage is a measure of electrical force or electrical potential. Voltage is symbolized by V and its unit is the Volt, V. We always discuss voltage in terms of voltage differences; that is, the difference in electrical potential between two points. For example, rather than a flashlight battery being 1.5 Volts, which is what we would say in common usage, the correct statement is, “The voltage is 1.5 Volts higher at the positive (+) terminal compared to the negative terminal (-).” Note, there is technically no such thing as a negative or positive voltage, even though we often slip into that usage. There are just differences in voltage or electrical potential. One spot may have a higher or lower voltage than another spot, but neither is positive or negative by itself, only in relation to another location.

Resistance. This term is hard to define without using the word itself. Resistance refers to the resistance a material possesses to the movement of charge (see, I used the word in the definition). Something with low resistance lets charge move easily compared to something with high resistance. Resistance is symbolized by the letter R and its unit is the ohm, which is symbolized by the Greek letter omega (Ω).

Conductance. Conductance is the ease with which a material will carry charge. That is, it is the inverse of resistance. It is symbolized by G and its unit is the Siemen. In the good old days, the unit of conductance was called a Mho, which is Ohm spelled backwards. I like this better because it is nice reminder that conductance is the reciprocal of resistance, or G = 1/R.

Capacitance: We won’t talk about this electrical property much, but for the sake of completeness, I include it. Capacitance refers to the ability to store or separate charge. It is symbolized by C and its unit is the Farad.

We now come to the first equation in the course and it is a big complicated one (not):

V = I x R

This equation is called ohms law and it describes how voltage, current and resistance are related. The law is a bit more intuitive if we rearrange it to:

I = V / R

In this form, it is easier to see how the terms we defined above relate to one another. The greater the voltage difference, the greater the current. Greater resistance, less current. It is even easier if we replace resistance with conductance (remember G=1/R):

I = V x G

Greater conductance, more current.

The Influence of Membrane Voltage (potential) on ion movement.

Let’s use Ohm’s law to describe how the voltage across a membrane influences the movement of ions. In case you haven’t already guessed it, V in this case refers to the voltage difference across the membrane. The current, I, refers to the movement of ions (i.e. charge, Q) through the ion channels, and G relates to how many channels are present and how easy it is for ions to pass through each channel. That is the easy part and it is easy because we are treating the membrane as ohmic. Being ohmic does not just refer to someone who is in a deep meditative state, repeating the word “ohm” over and over, it also refers to a material in which its electrical resistance is independent of Voltage. Most things are ohmic. The resistance, or conductance, of a material is a static property that stays the same regardless of voltage. In materials like this, current obeys Ohm’s law. Although some ion channels obey Ohm’s law, like the leak K channels I mentioned earlier, voltage-gated channels definitely do not obey the law. Since a change in voltage causes the gate in such a channel to open or close, their conductance (i.e. resistance) changes. In the case of these non-ohmic channels, the amount of current, i.e. the rate ions move across the membrane, is influenced by voltage in two ways. It moves charge, just like we discussed, but the voltage change also changes conductance and a change in conductance will also change current. It can be very complicated and we won’t consider this in more detail until after we discuss the resting membrane potential, in which the membrane voltage by definition is not changing – it is “resting.”

The Nernst Potential and the “Idealized” Cell

The closest thing we have to an idealized cell in the nervous system are glial cells. These are idealized because the membrane is permeable to only (or mostly) one ion, K+. In a cell permeable to only one type of ion, that ion will reach equilibrium. Recall from the previous chapter that equilibrium occurs because the effect of the concentration gradient is equal and opposite to the electrical gradient (i.e. the voltage). The voltage across a membrane that is permeable to only one ion can be calculated by the second equation we encounter in the course, the Nernst Potential equation. This equation was derived by none other than Dr. Nernst in 1880. This was well before scientists knew much about electricity in animal tissues. Rather, its main use was in making batteries. It turns out a battery is a lot like a cell membrane. The battery contains a membrane that separates two electrolytes (solutions of ions dissolved in water). Note, an electrolyte solution contains an equal number of positive and negative ions. For example, if the solution is NaCl, there will be the same number of Na+ ions as Cl– ions dissolved in water. Other than in micro- (or nano-) scopic regions, where there may be a brief surplus of one or the other, overall, there will be an equal number of positive and negative charges. That is, there will be no separation of charge, or voltage in the electrolyte solution. To generate voltage, the two electrolyte solutions must contain different concentrations of one or more ions and they must be connected (or separated from each other depending on how you look at it) by a membrane that is selectively permeable to only one ion in the electrolyte solutions.

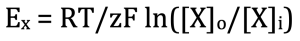

Here is how this arrangement generates voltage. Just like any molecule that has a higher concentration of one side of a membrane, the ion will diffuse from the electrolyte where it has a higher concentration to the one with a lower concentration. However, since this is an ion, it is not just an atom that is moving across, but this atom is an ion, so there is also movement of charge from one side of the membrane to the other. Since the membrane only lets one type of ion move, let’s say Na+ for example, the Na+ will diffuse but its counter ion Cl– will be left behind, creating a separation of charge. As Na+ continues to diffuse, one side of the membrane will have fewer Na+ ions than Cl–. On the other side, it will be the opposite. There will be more Na+ than Cl–. This net movement of Na+ will create a voltage and the Nernst equation was derived to calculate the size of the voltage. Here it is:

As you can see, this is a little more complicated than Ohm’s law. The good news is that we (you) only have to know and use a much-simplified version. First, let me explain the terms, then I will simplify the equation.

Ex refers to the voltage that will be generated across the membrane due to the movement of an ion that is just referred to as X in this equation. In reality it could be Na+, K+, Cl– etc. Unfortunately, the nomenclature here is a little confusing because Doc Nernst used E rather than V to refer to voltage. I will explain why he did this later in the chapter.

R is the gas constant. The important word here is “constant.” It is a number that never changes and you don’t need to know it because it becomes subsumed with the other constants, as you will see shortly.

T is temperature expressed in degrees Kelvin (K). The Kelvin temperature scale is similar to Celsius, but it is adjusted so that 0 degrees K is absolution zero, which is -273 degrees Celsius (-273.15 °C to be exact). On this scale, water freezes at 273 degrees K and boils at 373 K.

z refers to the valence of the ion. For Na+ and K+, z=+1. For Cl–, z=-1. And, for Ca2+, z =+2. Those are the only valences we neurobiologists need to consider.

F is Faraday’s constant. The same applies here as for the gas constant.

ln stands for natural logarithm, which is a mathematical function that you may not remember too well. If so, that’s fine because we won’t use it. The simplified version of the Nernst equation uses the more familiar log, which refers to base 10 logarithm. You know this even if you don’t think you do. It calculates the exponent that you must raise 10 to get the number. For example, log 10 = 1 because if you raise 10 to the power of 1 (101), you get 10. That is too easy. What is log 100? log 1000? log 10,000? log 1/10? The answers are 2 (102), 3 (103), 4 (104) and -1, (10-1). If you still don’t get it, let me know and I will give you some logarithm problems to work out (for fun)

[X]o is the concentration of the ion, X, on the outside of the membrane. Notice, I switched from a battery to a cell.

[X]i is the concentration of the ion, X, on the inside of the cell.

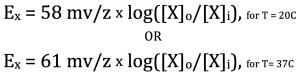

Now it is time to simplify. The first thing we can do is combine the two constants, R and F, into one number (they are both constants after all). The second thing we can do is to assume the temperature is constant. Most of the time, this assumption is perfectly fine since we are either considering cells in a mammal, which keeps its internal temperature at a constant 37 °C (300 K), or we are considering a cell in the lab which is at room temperature, 20 °C, (293 K). Finally, we can convert from natural logarithms (ln), which are not intuitive, to base 10 logarithms (log), which are more intuitive, by simply multiplying by 2.3. By combining all of these simplifications we come up with two much simpler versions of the Nernst equation:

These are the only versions of the Nernst potential that you will use. Let’s take an example. The chart below lists the concentrations of Na+, K +, Cl– and Ca2+ inside and outside a typical mammalian cell. There are other ions distributed across a typical cell, but they are not included here because they can’t move across the membrane and thereby do not influence the voltage.

| Ion | Intracellular Concentration

. (mM) |

Extracellular Concentration

. (mM) |

| Na+ | 10 | 145 |

| K+ | 140 | 5 |

| Cl– | 10 | 110 |

| Ca2+ | 1 x 10-4 | 2 |

Using these concentrations, we can calculate the Nernst potential for any of these ions.

Consider Na+. Since this is a mammalian cell, let’s assume it is at 37C. Then,

ENa = 61 mV/z x log([Na]o/[Na]i). If we plug in the numbers, we get

ENa = 61 mV/1 x log(145/10), which simplifies to ENa = 61 mv x log(14.5).

The log of 14.5 is 1.16. Of course, the way you get this number is by pressing the log button on your calculator or computer, but you should also note that the log of 14.5 must be a number between 1 and 2. Why? Because 14.6 is greater than 10, which has a log of 1, and it is less than 100, which has a log of 2.

Going on, 61mv x 1.16 = 69.7 mV. Let’s think about what this means. It says that if a mammalian cell is permeable exclusively to Na+, the voltage across its membrane will be 69.7 mv. Because of how we set up the Nernst equation, with the external concentration on top and the internal concentration on the bottom, the voltage we calculate tells us the voltage on the inside relative to the outside. Thus, in our example, the voltage inside the cell is 69.7 mv higher than the outside.

You should spend some time thinking through this example and making sure you can follow the logic. In this case, why is the voltage inside the cell higher than outside? What would happen to the size of this voltage if we doubled the concentration of Na+ on the outside (and kept the inside concentration the same)? What if we doubled the concentration of Na+ on this inside? First, you should try to reason your answer, then check your reasoning by calculating the new Nernst potential. After you feel like you understand, do the same for the other ions. (Remember that z is -1 for Cl– and +2 for Ca2+). After calculating the Nernst potential for each of these ions, ask yourself if the numbers make sense. Would you predict a positive or negative voltage? (A negative answer means the voltage inside the cell is lower than the outside.). How would the voltage change if you doubled the concentrations of each of these ions on the inside? The outside?

A Real Cell: the effect of other ions

Our discussion so far applies only to an idealized cell, by which we mean a cell that is permeable to only one ion. We say this is idealized because it never happens in real life (it is only true in a platonic sense). In real cells, the membrane will have more than one type of ion channel. We say it is permeable to multiple ions (depending on the number of open ion channels in the membrane at any given time). Because of this, none of the ions can ever reach equilibrium. You should pause and think for a minute why this is the case.

This might be a good time to revisit the Nernst equation and explain why Dr. Nernst used E rather than V to stand for the voltage across the membrane in the ideal cell. He used E because the Nernst equation calculates what is called the Equilibrium potential. (Recall, this was briefly referenced in the previous chapter.) According to Miriam Webster, “Equilibrium refers to a state of balance between opposing forces or actions.” In this case, it calculates the membrane voltage that completely balances the influence of the ion’s concentration difference across the membrane. Take Na+ for example. Since there are more Na+ ions outside than inside, this difference pushes Na+ ions into the cell. However, as Na+ ions diffuse in, the voltage inside of the cell becomes higher than the outside because the Na+ ions leave their negative partners, Cl–, behind, as I discussed above. This change in voltage will now try to push the Na+ back out of the cell since positive ions will be pushed in the direction of the voltage gradient, from high to low. Na+ ions will keep flowing into the cell until the voltage gets high enough inside to push Na+ out just as fast as the concentration difference is pushing it in. This point is equilibrium and it is the voltage, ENa, calculated by the Nernst equation.

At this point in the discussion students usually ask, “but hasn’t the concentration gradient changed? After all, some Na+ ions diffused into the cell before the voltage built up high enough to push them back out at the same rate they are diffusing in.” The answer is yes, there is a little bit less Na+ on the outside and a little more Na+ on the inside because of the diffusion of Na+ that occurred prior to reaching equilibrium; however, it was a very tiny amount. It doesn’t take the diffusion of many Na+ ions to generate a sizeable voltage. It won’t change the concentrations enough to be measurable or to have an effect.

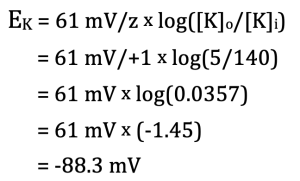

Hopefully, now you can see why it is impossible to reach equilibrium if the cell membrane is permeable to more than one ion. If you look back at the Nernst potentials you calculated, you will notice that each ion has a different equilibrium potential. Each potential is different because the different ions are distributed differently across the membrane. Consider K+. If you haven’t already done so, calculate EK. I will walk through it here:

Hopefully, this is the number you calculated. What does it mean? Well, in an ideal cell that is permeable only to K+, it will reach equilibrium when the voltage inside the cell is 88.3 mV less than the outside. This is the point where the diffusion of K+ out of the cell because of its concentration gradient (higher inside than outside) is balanced by the negative voltage inside the cell which pulls the K+ back inside. Obviously, this will never happen if the cell is also permeable to Na+, since the diffusion of Na+ has the opposite effect on voltage. This brings us to real cells. The Nernst potential no longer applies and we must turn to the third equation we come to in this course, the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) equation.

The Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) Equation

Before discussing this new equation, which was created to predict the voltage across a membrane in a cell with more than one permeable ion, let’s see if we can predict what will happen. Imagine a cell that has an equal number of open K+ and Na+ channels. What will the voltage settle at? We have already established that the voltage would be -88.3 mV if K+ ions were the only ones that could cross the membrane and that the voltage would be +69.7 mV if it was all Na+ ions. What if both had an equal shot? Where will the voltage end up?

K+ is pulling the voltage to -88.3 mV and Na+ is pushing it to +69.7 mV. If there are the same number of each kind of channel, the voltage will end up halfway between, which is -9.3 mV. At this voltage, neither ion is at equilibrium, but each ion is equally far away from its equilibrium voltage. Thus, although there are still Na+ ions entering the cell and K+ ions leaving, the same number are moving each way so there is no net movement of charge across the membrane. We say that the membrane voltage is at steady-state. It will stay steady at -9.3 mV; however, since Na+ and K+ are still moving across the membrane, we do have to worry about the concentrations changing. Note; steady-state is not the same as equilibrium, although in both cases the voltage will be constant. We will come back to this problem later.

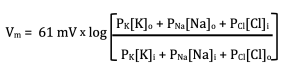

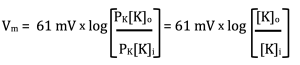

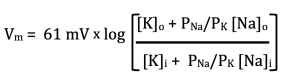

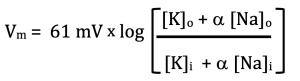

We have now considered three possible states of the membrane; only Na+ channels, only K+ channels, and 50-50 Na+ and K+ channels. What about 90% K+ channels and 10% Na+? For these more complicated, and unfortunately realistic, scenarios, we will need the GHK equation. However, want to take a guess? Did you guess that the voltage will now settle at a level closer to Ek than ENa? If not, that is okay. This is where the GHK comes in to play:

You should recognize the 61 mV, which is the same number we used in the Nernst equation for a temperature of 37 °C (mammalian body temperature). That also applies for the GHK equation. To use the GHK equation for a temperature of 20 °C (room temperature), you should use 58 mV.

The new variables in this equation are PNa, PK and PCl. These are the permeabilities of the membrane to Na+, K+ and Cl–. What this equation does is multiply (or weight) each concentration by its permeability. The more permeable an ion is, the more its concentration influences the final voltage, which is just what we predicted. To make this point clearer, what happens to the GHK if the membrane is only permeable to K+? In this case, PNa = PCl = 0 and the equation simplifies to:

Recognize this? We are back to the Nernst potential. That is, the GHK equation calculates the same voltage as the Nernst equation if only one type of ion is permeable.

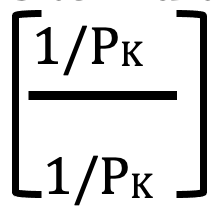

Before we leave this consideration of the GHK equation, I would like to make one mathematical change. A fairly simple manipulation that can be made to any algebraic expression is to multiply it by 1. Obviously, this doesn’t change anything. But what if we multiply by

This is also 1, but look what happens to the equation when we do this:

Before you start complaining that I made the equation more complicated, notice what happens when I replace PK/PK by 1:

Okay, maybe it still is more complicated, but notice what it shows us now. The membrane voltage is determined by the concentrations of ions across the membrane, which we already knew, and the ratios of the ion permeabilities. The absolute permeabilities do not matter, just the relative permeabilities of the ions.

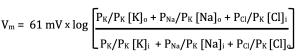

I have one more simplification of the GHK before I present it to you in the form you need to remember. But, before I do that, look at the terms related to Cl–. Did I make a mistake and accidentally switch [Cl–]o and [Cl–]i? Although, I am not above making that kind of mistake, in this case it was not. They were switched deliberately because Cl– is a negative ion. It has the opposite response to voltage than positive ions do. We accommodate this difference by flipping the numerator and denominator of this term.

With that, here is the final simplification. I will never ask you to consider the influence of Cl– on membrane voltage. It does make a difference, but not that much, at least not in the cases we will be considering. Thus, presenting the new and improved GHK: equation:

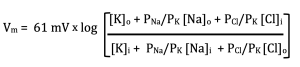

Or, if we define α as the ratio of Na permeability to K permeability (PNa/PK):

Now, we are finally ready to consider a real cell. Neurons and muscle cells spend most of their time “resting.” They are not resting the way you might think. In fact, these “resting” cells are using up lots of ATP as we will see shortly. The term resting refers to the fact that they are not actively signaling. They are in between signals, just “resting.” In this state, the membrane is mostly permeable to K+. This is because of the leak K+ channel I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter. The other ion channels in the membrane are mostly closed; however, there are a few open Na+ channels. Typically, this might translate to a permeability ratio of 1:100. That is, α = PNa/PK = 1/100. If we plug that into the GHK equation along with the concentrations of Na+ and K+ shown above in the table for mammalian cells, we calculate Vm = -81.5 mV. Try it yourself and make sure you can get this number. What it says is that the resting membrane potential of this cell is -81.5 mV. This is just what we predicted above: that it would be between Ek, which is -88.3 mV, and ENa, which is 69.7 mV. We also predicted that it would be closer to EK.

The Na+/K+ Pump

We now return to a problem alluded to earlier. In real cells, none of the ions are at equilibrium. That means there is constant net diffusion across the cell membrane. Even at rest, when there is no net movement of charge across the membrane, the individual ions are still moving. That is, there may be an equal number of Na+ ions diffusing into the cell as there are K+ ions diffusing out. Thus, unlike in an ideal cell, the concentrations of the ions will start to change over time. If the cell does not compensate for this, the concentration gradients (differences across the membrane) will disappear and the cell will no longer be able to function. Fortunately for all of us, this doesn’t usually happen.

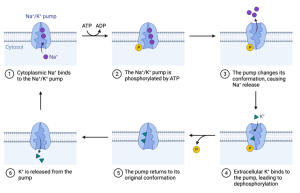

Cells contain several mechanisms to help maintain the proper concentration of ions, but by far the most important one is the Na+/K+ pump. This is also referred to as the Na+/K+ ATPase. The Na+/K+ pump (or ATPase) is a complex membrane protein that pumps 3 Na+ ions out in exchange for 2 K+ ions that are pumped into the cell. It gets the energy to do this by splitting a molecule of ATP into ADP and Pi. The complete cycle of the pump is depicted below.

The activity of this pump opposes the slow leak of Na+ into and K+ out of the cell. To illustrate the importance of this one protein, physiologists have estimated that between 25 and 50% of the energy required by the nervous system is used to drive the Na+/K+ ATPase in the membranes of the neurons in the brain.

You might wonder why more Na+ ions are transported than K+ ions. There are probably several reasons, but two quickly come to mind. First, when the cell is at rest, which is most of the time, more Na+ ions will leak in than K+ ions will leak out. Second, because of this 3 to 2 stoichiometry, during every cycle of the pump, a net positive charge is moved out of the cell. This makes the inside of the cell slightly more negative. Because of this, the pump is said to be electrogenic. That is, its activity generates some of the voltage across the membrane. Note, this is a direct effect of the pump that is in addition to its indirect effect on membrane voltage by virtue of maintaining the Na+ and K+ concentration gradients. The electrogenic effect of the Na+/K+ ATPase is a fraction of the size of the effect of ion diffusion.

As is true of many of the proteins that play key functions in the cell, we have learned a lot about the role and importance of the Na+/K+ pump by a chemical (i.e. a drug) that specifically inhibits it. In this case, the drug is called ouabain (pronounced oo-ah-bane). Oubain attaches to the site on the pump that normally binds the K+ ions and thereby mucks up the machinery, stopping the pump in its tracks. A cell that relies on the Na+/K+ pump to function (and this is true of all neurons) will be poisoned by oubain. Digitalis is another drug that has a similar effect to ouabain. Digitalis, also called digoxin, is a heart medicine derived from the plant Digitalis purpurea, commonly known as foxglove. Not surprisingly, given its mechanism of action, the leaves, flowers and seeds of the plant are highly toxic and can even be fatal.

Foxflove (Digitalis Purpurea)

Media Attributions

- NernstEquation_C4

- NernstEquation_Simpler_C4

- Screenshot 2024-11-13 at 14.13.26

- Screenshot 2024-11-13 at 14.15.43

- Screenshot 2024-11-13 at 14.16.25

- Screenshot 2024-11-13 at 14.17.57

- Screenshot 2024-11-13 at 14.18.46

- Screenshot 2024-11-13 at 14.19.18

- Screenshot 2024-11-13 at 14.19.58

- Screenshot 2024-11-13 at 14.20.34

- NaKpump_C4

- Foxflove_C4