50 Molecular Mechanisms of Memory: Hippocampus

Zooming in beyond the level of anatomy, the substrates of learning can be found at the level of synapses. Synapses change in a phenomenon called plasticity. The word “plasticity” refers to a change in synaptic strength, which may be an increase or a decrease. This change may persist for minutes, hours, days, or in some cases, even a whole lifetime.

When synaptic strength is increased and remains elevated, we call this long-term potentiation (LTP). A prolonged weakness of a synapse is called long-term depression (LTD). In our current limited understanding of plasticity, both phenomena are important for a healthy brain, and neither one is always good or always bad. It is also important to clarify that both excitatory synapses and inhibitory synapses can be subject to either LTP or LTD.

The Hippocampus

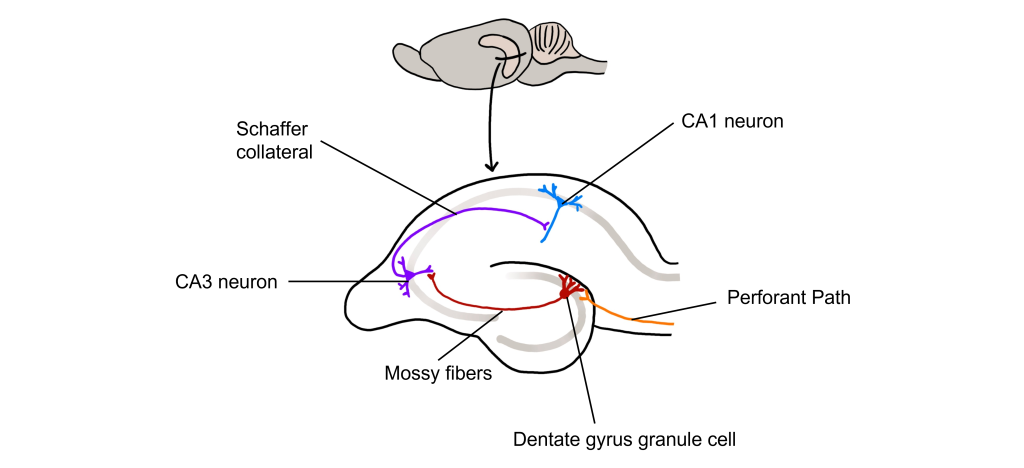

The hippocampus, meaning “seahorse” in Greek, was named based on its morphology. It is located along the ventral and medial surface of the brain. The hippocampus serves as one of the critical structures of the limbic system, a series of subcortical brain structures that are involved in several different complex behaviors, such as emotions and memory. The synaptic connectivity of the hippocampus is very well characterized. Hippocampal synaptic connectivity was first described by Ramon y Cajal, and is made up of three main synaptic connections; sometimes called the trisynaptic circuit.

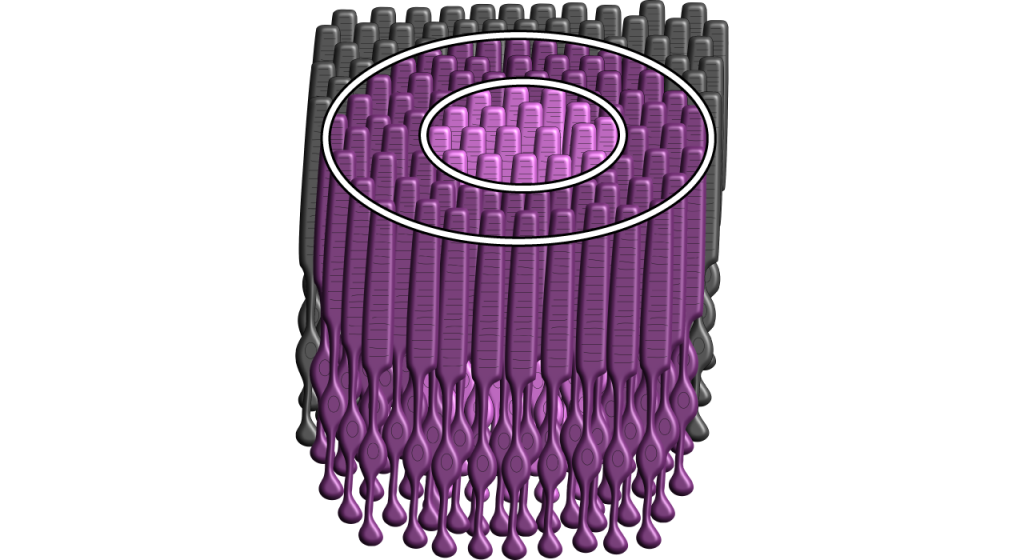

First, the entorhinal cortex serves as the major input to the hippocampus. This white matter signaling tract is called the perforant pathway, and the neurons synapse onto the granule cells within an area of the hippocampus called the dentate gyrus. The dentate gyrus neurons send their axons, called mossy fibers, to the pyramidal cells of the CA3 region of the hippocampus. The CA3 neurons have axonal projections called Schaffer collaterals that project out of the hippocampus via the fornix and also to neurons within an area of the hippocampus called CA1, which are also neurons that serve as an output of the hippocampus.

Long-Term Potentiation (LTP)

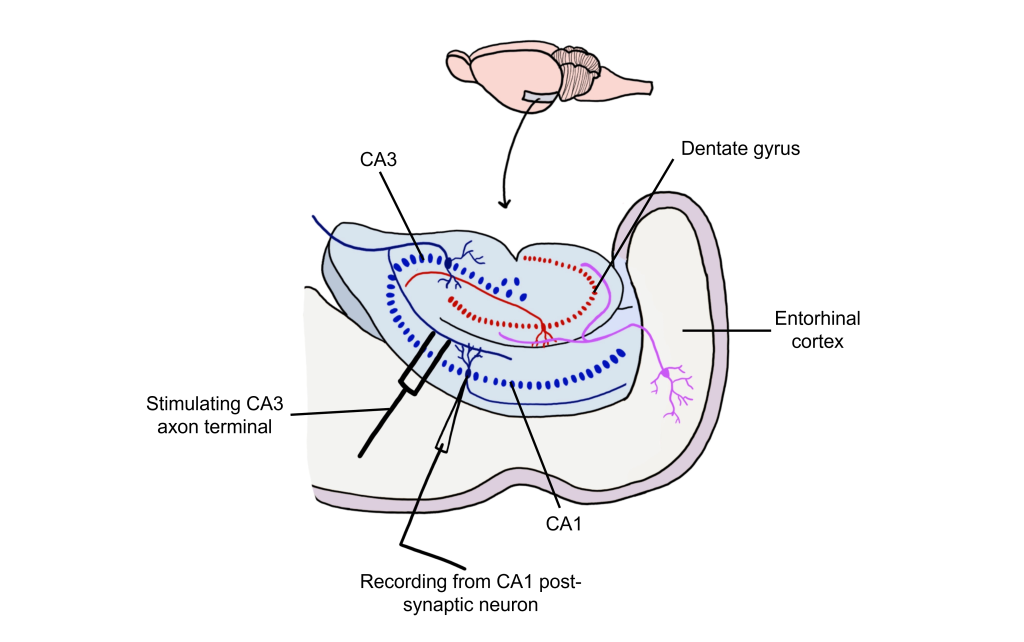

Long-term potentiation (LTP) is a long-lasting increase in synaptic strength, measured by the amplitude of the post-synaptic potential. Plasticity can be measured throughout these connections, but for our purposes we will examine how to create LTP within the Schaffer collateral.

To create LTP within the Schaffer collateral, a brief electrical stimulus must be provided to the presynaptic axons coming from the CA3 cells via a stimulating electrode. The EPSP generated in the postsynaptic CA1 neurons is then measured with a recording electrode to establish a baseline.

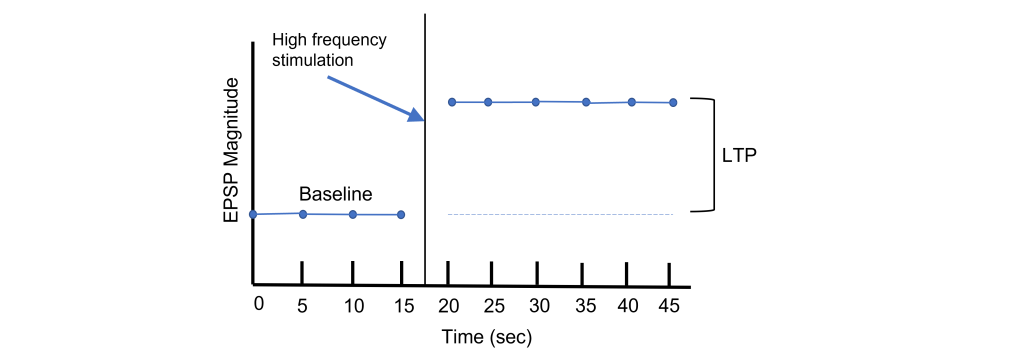

Using Hebb’s theory about plasticity, if “cells that fire together, wire together,” then it stands that repeated stimulation of that synapse would induce a rewiring of the connection, resulting in LTP. To induce LTP within these cells, a tetanus, or a very intense electrical stimulation consisting of 100 stimulations a second (100 Hz) is delivered to the presynaptic CA3 cells for 3 seconds. Following the delivery of tetanus, a single stimulus is provided again and the EPSP is then measured in the postsynaptic CA1 neuron. The delivery of the high frequency stimulation results in an increased amplitude of the postsynaptic EPSP in response to a single stimulus, demonstrating that LTP is a measurable phenomenon.

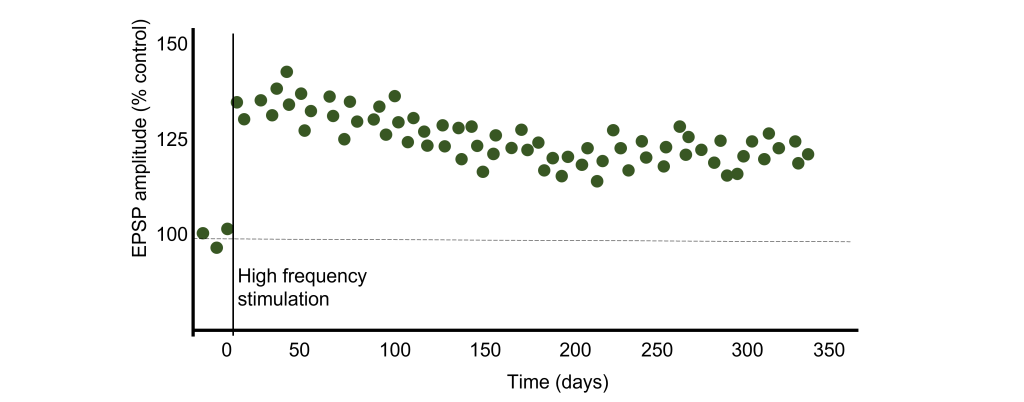

In many cases, LTP is shown graphically by measuring the EPSP amplitude as a percent of the control EPSP amplitude. Prior to tetanus delivery, the amplitude will be measured as 100%, or the same as control. Following tetanus, the amplitude of the EPSP will be larger than it was baseline, for instance 130% indicating a 30% increase in amplitude. Increasing the amplitude of the postsynaptic EPSP increases the likelihood of a neuron firing an action potential by increasing the neuron membrane potential such that it is closer to the threshold potential for the cell.

It has been demonstrated in rodents that the elevated postsynaptic EPSP response is long-lasting and can remain elevated for upwards of one year. In humans, we theorize that some synaptic connections may remain potentiated for our entire lifetime, however investigating this is in humans is ethically constrained.

Glutamate Receptors and LTP

Long-lasting changes in synaptic strength, such as the LTP, are made possible through a series of molecular and cellular level changes. One form of LTP results from a change in the types of glutamatergic receptors. Of the three classes of ionotropic glutamate receptors, two are important for this form of LTP: the AMPA and the NMDA receptors (Chapter 16).

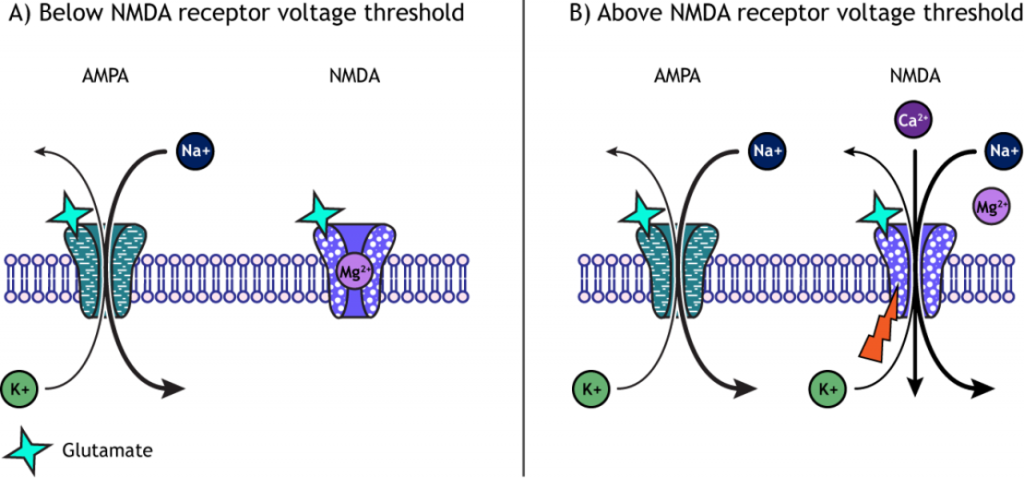

When a molecule of glutamate binds to the active site of the AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid) receptor, the ligand-gated ion channel changes to the open conformation and allows the cations, sodium and potassium, to cross the cell membrane. Sodium moves into the cells more than potassium leaves the cell, leading to depolarization. The NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor requires the binding of glutamate to open, but it is also dependent on voltage. The pore of the NMDA ligand-gated ion channel is blocked by a molecule of magnesium when the membrane potential is below or near resting membrane potential, preventing ions from moving through the channel. Once the cell depolarizes, the magnesium block is expelled from the receptor, which allows sodium, potassium, and calcium to cross the membrane.

The voltage change needed to open the NMDA receptor is usually a result of AMPA receptor activation. Released glutamate binds to both AMPA and NMDA receptors, and sodium influx occurs through open AMPA channels, which depolarizes the cell enough to expel the magnesium ion and allow ion flow through the NMDA receptors.

LTP and Intracellular Calcium

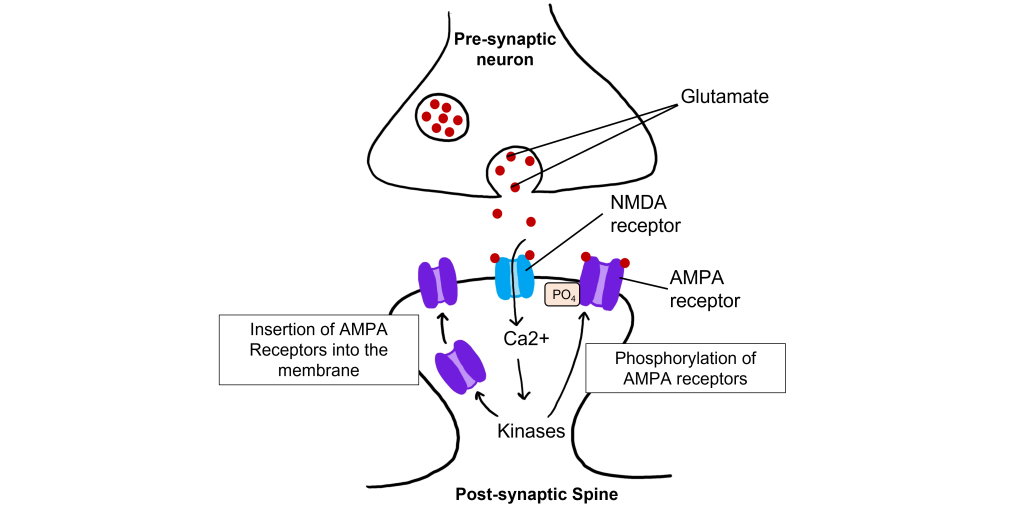

The calcium that enters the cell through the open NMDA receptors activates various kinases including, protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase C (PKC), and calcium-calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CAMKII). Kinases phosphorylate target proteins within the cell, including AMPA receptors. Phosphorylation of AMPA receptors increases their conductance, allowing more ions to pass through the receptors and leading to a greater degree of depolarization. Further, increased intracellular calcium can lead to the insertion of additional AMPA receptors into the postsynaptic cell membrane, which will also allow more sodium to move into the cell and lead to increased depolarization.

Long-Term Depression (LTD)

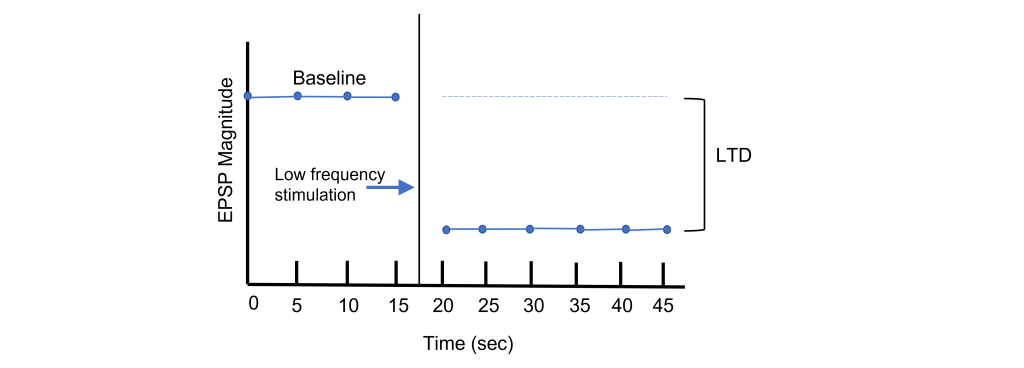

Long-term potentiation increases the strength of synapses. Changes in activity can also cause synapses to be weakened through the process of long-term depression (LTD). Again, using the Schaffer collateral as an example, long-term depression can be induced at the synapses between the CA3 and CA1 neurons by replacing the tetanus stimulation with low-frequency stimulation for longer periods of time. For instance, a 15 min exposure to 1 Hz stimulation will lead to a decreased EPSP amplitude.

Through LTP and LTD, synapses demonstrate bidirectional plasticity that is dependent on the type of stimulation that the synapse receives.

LTD and Intracellular Calcium

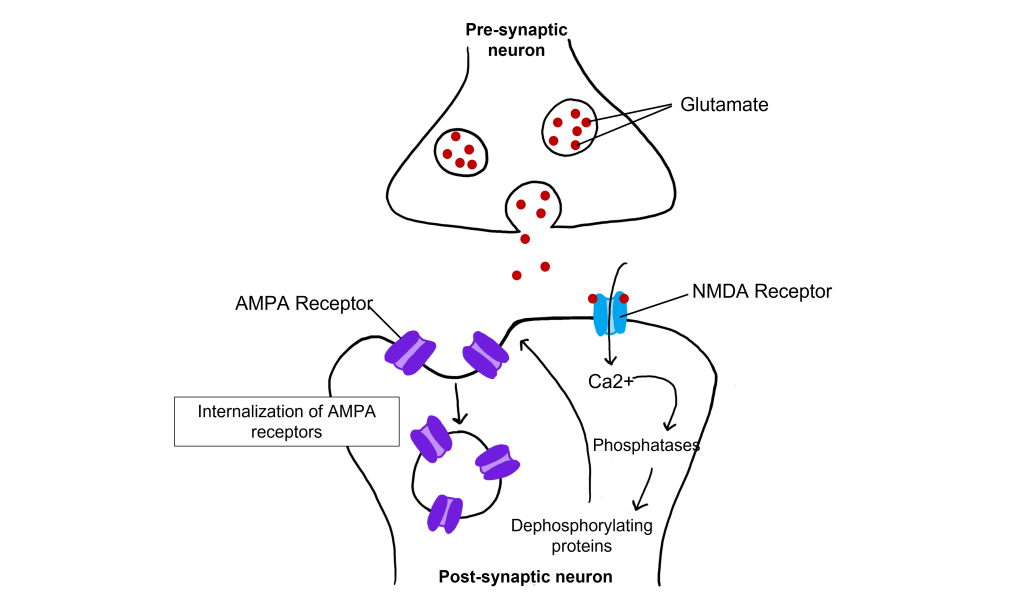

Even with low-frequency stimulation of the synapse, glutamate will bind to post-synaptic NMDA receptors and allow for the influx of calcium into the cell. Weak depolarization of the membrane leads to a low amount of calcium entering the cell, which activates a separate class of enzymes call protein phosphatases, specifically protein phosphatase 1 and protein phosphatase 2, that remove phosphate groups from target proteins. Further, LTD causes AMPA receptors to be internalized, or removed from the postsynaptic membrane. Removal of AMPA receptors will decrease excitability.

Relating LTP to Learning

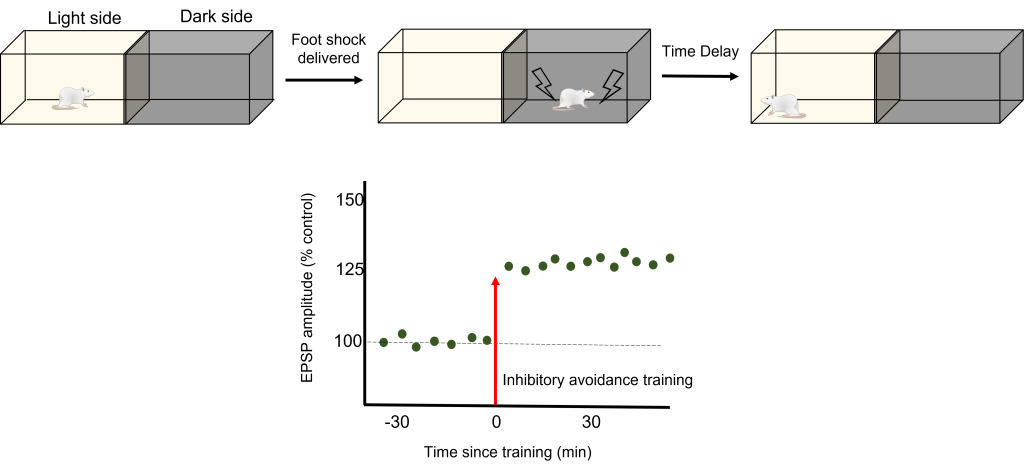

To test how LTP And LTD are directly related to memory, a robust model of learning is used called Inhibitory Avoidance. In an inhibitory avoidance task, a rat learns to associate an environment with an aversive experience. Typically, a two-chamber compartment is used with one light side and one dark side. The animal is permitted to move from the light chamber to the dark chamber, where it receives an electric foot shock. After just one trial with this protocol, the animal will learn to avoid the dark chamber where it received the foot shock.

One trial of inhibitory avoidance led to measurable LTP within the Schaffer collaterals, demonstrating that the behavioral learning corresponded to LTP during this task. Administration of an NMDA receptor blocker to the hippocampus prior to inhibitory avoidance training results in the animals being unable to learn that the dark chamber leads to a foot shock and inhibition of the corresponding LTP.

Key Takeaways

- Plasticity in the form of LTP and LTD occurs at both inhibitory and excitatory synapses.

- The hippocampus has a trisynaptic circuit of connections.

- Long-term potentiation (LTP) is a long-term strengthening of a synapse, whereas long-term depression (LTD) is a long-term weakening of a synapse.

- LTP is demonstrated by observing an increased EPSP amplitude following a tetanus.

- LTD is demonstrated by observing a decreased EPSP amplitude following low frequency stimulation.

- AMPA and NMDA glutamate receptors are important in LTP.

- High levels of intracellular calcium from high frequency stimulation activates protein kinases, which leads to increased conductance of AMPA receptors and insertion of AMPA receptors in the cell membrane.

- Low levels of intracellular calcium from low frequency stimulation activates protein phosphatases, which leads to decreased conductance of AMPA receptors and removal of AMPA receptors in the cell membrane.

- Inhibitory avoidance is a robust learning model in which animals only need one trial before learning occurs. It has been show to also induce LTP.

Attributions

Portions of this chapter were remixed and revised from the following sources:

- Open Neuroscience Initiative by Valerie Hedges. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Media Attributions

- Rodent hippocampus trisynaptic circuit © Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Schaffer collateral LTP © Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- LTP Graph © Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Graphing postsynaptic response as a percent of control © Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- AMPA NMDA © Casey Henley is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Calcium and LTP © Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- LTD graph © Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Calcium and LTD © Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Inhibitory avoidance © Valerie Hedges is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

A diffusion barrier that prevents some of the substances circulating in the blood to pass to brain tissue.

Non-neuronal cells of the nervous system.

Although we mostly think about the neurons that make up the brain and spinal cord as being the main characters of the nervous system, there are many other anatomical features that play important supporting roles. These are often non-neuronal structures that are still critically important in allowing the nervous system to do what it needs to do.

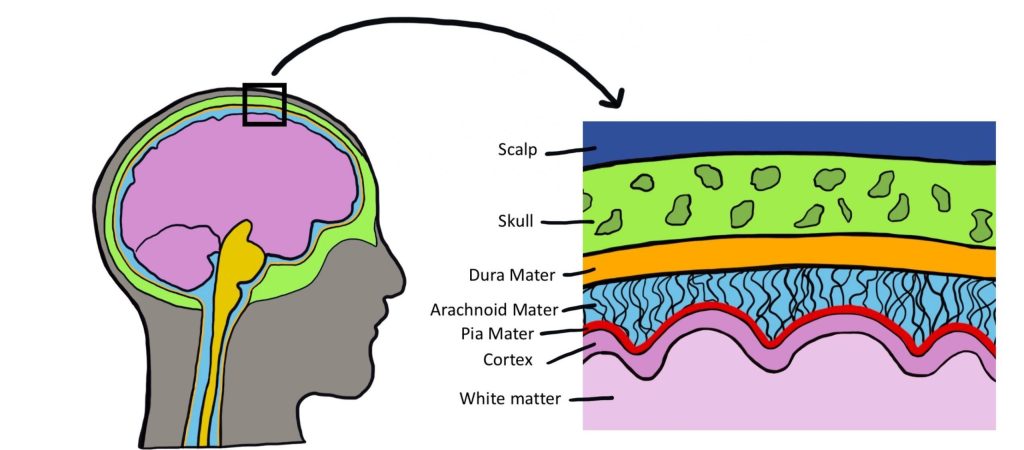

Meninges

The brain is a soft and delicate internal organ housed inside the skull. If there weren’t some protective buffer separating the soft brain matter from the rigid bone, the jelly-like brain would be smashed up against the inside of the skull and get injured as the head moves around.

The meninges are a series of protective membranes that minimize this kind of damage. They surround the brain and extend all the way down the spinal cord. Think of the meninges as an organic type of “bubble wrap” that encases a fragile nervous system.

There are three types of membranes that collectively make up the meninges. From the outermost to innermost layer, they are:

- Dura mater. The dura is made of thick, fibrous material and can get to be 0.8 mm thick in the adult body (if you took a piece of printer paper and fold it in half four times, that should give you an idea of how thick the dura mater is in the adult human). The dura mater is physically attached to the inside of the skull with highly resilient connections found at the sutures between the plates of the cranium. The name originates from Latin meaning "tough mother".

- Arachnoid mater. The arachnoid mater is the middle layer of the meninges. The fibers are very delicate and resemble a spider web, which is where the name comes from. Within this space, there are protrusions that allow for CSF to drain into sinuses, which allow for recycling of soluble substances. Most of the CSF in the brain exists underneath this layer in the subarachnoid space.

- Pia mater. The pia mater is the third layer of the meninges. It is very fragile, is in direct contact with the surface of the brain, and closely follows the sulci and gyri. The name means "pious mother".

Meningitis

Inflammation of the meninges is a potentially deadly condition called meningitis. Exposure to infectious agents like viruses or bacteria such as Neisseria meningitidis (that leaks from the blood into the meninges) is a common cause of the inflammation. When the meninges are inflamed, the brain gets compressed from all sides, increasing intracranial pressure, producing many of the same symptoms seen in hydrocephalus: fever, stiff neck, headache, seizures, and altered mental status. The N. meningitidis bacteria and the viruses are highly transmissible in close contact, but vaccinations are highly effective at minimizing the infection rate. As with bacterial infections, broad-spectrum antibiotics are effective at treating the infection.

Brain Circulation

Like every other organ in the body, the brain requires oxygen and nutrients to function. In humans, this function is accomplished by the blood that is pumped around the body using a network of blood vessels called the circulatory system. The brain has a very high demand for oxygen and nutrients: at only 2% of total body weight, it receives about 15% of total cardiac output.

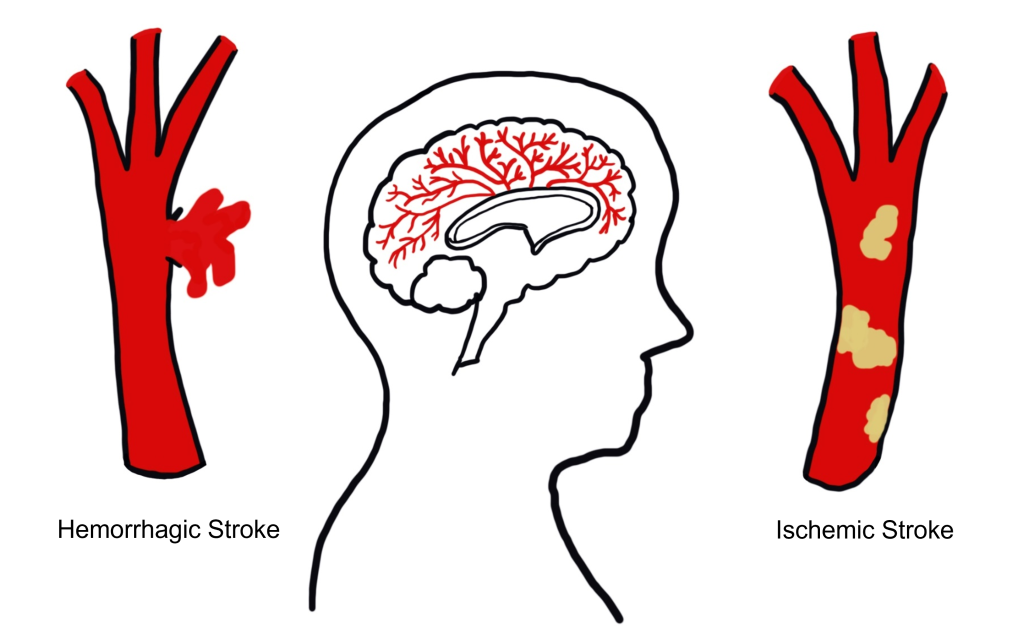

Stroke

Stroke is an extremely common, life-threatening medical condition that results in a loss of blood flow to the brain. According to 2016 statistics from the World Health Organization, stroke is the second-highest cause of death worldwide. The number one risk factor for stroke is high blood pressure. There are two common types of strokes that a person may experience.

More than 80% of all strokes are ischemic strokes (pronounced is-keemik), which happens when normal blood flow is interrupted, causing cell death by deprivation of oxygen and nutrients to brain tissue. Generally, this type of injury can happen when a blood clot forms, travels through the circulatory system, and gets lodged in a tiny brain blood vessel, thus, blocking the passage of blood.

The other 20% of strokes are hemorrhagic strokes, which result from a burst blood vessel that causes bleeding into the brain. The presence of uncontrolled blood inside the brain causes an increase in intracranial pressure, which can be lethal. Many brain cells may die since they cannot take up oxygen directly from the blood. Additionally, blood has dramatically different properties than the normal solution brain cells live in, and this can cause the neurons to trigger a self-destruction program. Generally, hemorrhagic stroke is more deadly than ischemic stroke.

Because the different blood vessels of the brain’s circulatory system are responsible for providing blood to specific areas of the brain, it is possible to diagnose the specific area where the stroke is happening based on the presentation of symptoms. For example, if the middle cerebral artery blood is occluded by an ischemic stroke, the left hemisphere motor cortex will lose blood flow. Because of the contralateral organization of the descending motor pathway, the patient may therefore present with paralysis or weakness in the right half of the body. It is vitally important to correctly diagnose and differentiate between the two types of strokes. An ischemic stroke may be treated with injection of a “clot-busting” drug, a substance that helps the body break down the offending blockage. However, these clot-busters could make the bleeding from a hemorrhagic stroke even worse.

Blood–Brain Barrier

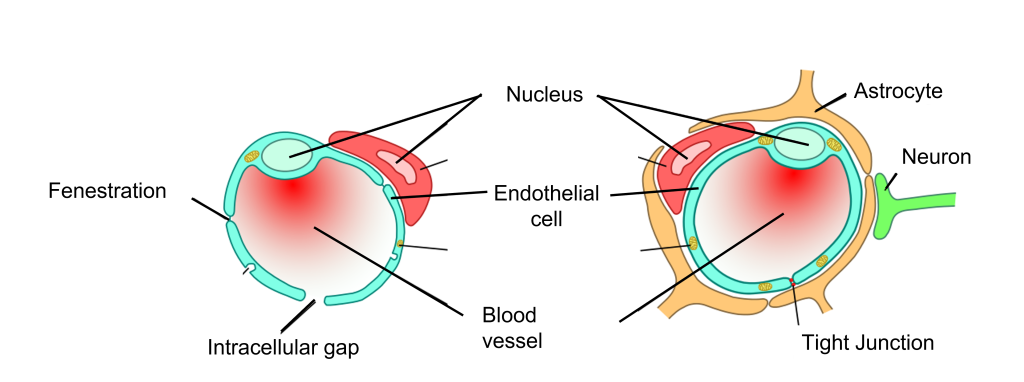

It is important for oxygen and nutrients to pass from the blood into the brain tissue. Small blood vessels outside of the brain, such as the capillaries in the fingertips, have very thin walls—sometimes the width of a single cell—and are, therefore, highly permeable to gases. These vessels can either contain tiny holes or large protein structures that physically transport substances across the blood vessel. On the other hand, it is also advantageous to separate toxins and foreign pathogens in the bloodstream from getting into brain tissue.

The blood–brain barrier (BBB) is an anatomical adaptation that selectively transports substances necessary for normal biological function, while simultaneously excluding potentially harmful invaders from the brain. The BBB physically surrounds blood vessels in the brain. It is made up of endothelial cells and a type of glial cell called an astrocyte. The BBB is injured in a variety of medical disorders, ranging from stroke, epilepsy, and Alzheimer’s disease, just to name a few. It is still unknown what role the disruption of the BBB plays in brain disorders.

The exclusive nature of the BBB can be a double-edged sword. It is difficult to deliver a drug into the brain from the blood stream if that drug is unable to pass through the BBB. For example, the current gold standard pharmaceutical treatment for Parkinson’s disease is to increase the brain’s levels of dopamine. However, dopamine does not pass through the BBB. To get around this, physicians give the BBB-permeable substance L-DOPA, which the brain is able to convert into dopamine. Many other therapeutic drugs do not cross the BBB, so researchers are developing methods using electromagnetic fields to temporarily weaken the barrier, or surround the drugs in nanoparticles so small that the body cannot identify them as foreign.

Ventricles

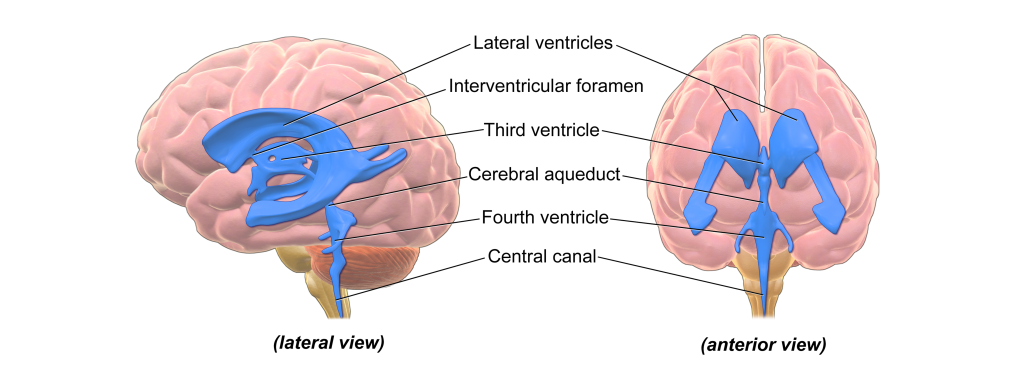

There are hollow spaces within the brain called ventricles. The human brain has a total of four ventricles. The two very large, paired ventricles (one in each hemisphere) are the lateral ventricles. They are connected medially to the third ventricle, which extends to the posterior aspect of the brain. From here, the cerebral aqueduct that runs ventrally extends into the fourth ventricle before continuing into the central canal: a narrow space that runs all the way through the length of the spinal cord along the midline.

The entire ventricular system is interconnected. The ventricles are filled with a liquid called cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF is basically a high-salt water solution. Because of the high osmolarity of CSF, it is a very buoyant solution. Like a fully grown person who can float easily on the surface of the extremely salty Dead Sea, CSF allows the brain to remain “floating” inside the skull. Without CSF, the brain weighs almost 1.5 kg (~3 lbs). Cells and blood vessels at the ventral base of the brain would be crushed under the weight of the brain itself. But when the brain is surrounded by CSF, it weighs less than 50 grams, almost two orders of magnitude lighter!

CSF is also found within the meninges that encase the brain. In fact, more than 80% of the CSF in the body exists in this space outside the brain. This liquid serves as a form of “cushioning” that protects the brain from rapid head movements. If it weren’t for this physical protection, the inertia of head movement may cause your brain to smash against the inside of the rigid skull if you move your head too quickly.

The CSF layer allows the head to withstand some sloshing of the brain, but a movement that is too abrupt can cause a traumatic brain injury. CSF can also function as a way to wash impurities out of the brain. The volume of CSF in the typical human body is about 150 mL, a little more than half a cup. Because there is frequent turnover of CSF, the material gets absorbed back into the body regularly. Each day, the body produces about half a liter of CSF, so the brain cycles through the entire volume a few times.

Hydrocephalus

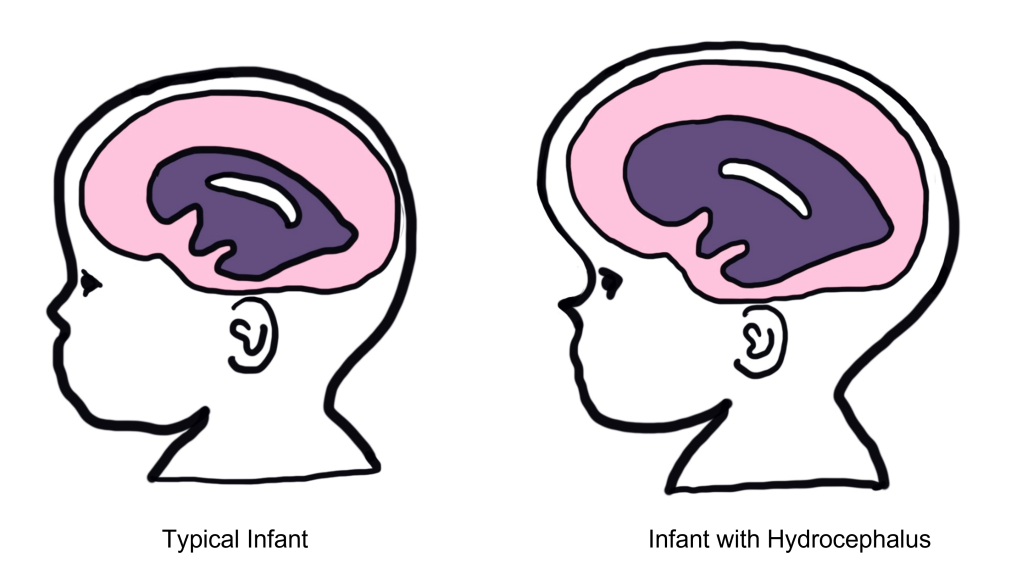

Hydrocephalus, historically called “water on the brain”, is a common condition affecting the brain of about 1 in 200 newborns and a small number of adults. In patients with hydrocephalus, the volume of CSF increases, which elevates intracranial pressure, causing symptoms such as fever, stiff neck, headache, seizures, or altered mental status.

In adults, the skull is rigid and unmoving. But in newborns with hydrocephalus, the plates of the skull are not completely fused together. Often, these children will have a bulging parts on the skull and an expansion of the forehead.

Increased CSF volume can happen in a couple ways. The clearance of CSF may fail while production remains normal, or the entrance to the central canal in the spinal cord may be narrowed or blocked by a tumor, leading to an increase in the volume in the brain. A common treatment for hydrocephalus is to surgically implant a shunt (a hollow tube that runs from the ventricle down into the abdominal space) that allows for drainage, thus decreasing intracranial pressure.

Key Takeaways

- The meninges are protective coverings that cover central nervous system structures

- There are two types of stroke: ischemic (blocked blood vessel) and hemorrhagic (burst blood vessel)

- Ischemic strokes account for 80% of strokes and hemorrhagic strokes account for 20% of strokes

- The blood–brain barrier surrounds blood vessels of the brain to restrict the substances that can enter the brain

- Ventricles are hollow spaces in the brain that are filled with cerebral spinal fluid

Test Yourself!

Attributions

Portions of this chapter were remixed and revised from the following sources:

- Open Neuroscience Initiative by Austin Lim. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Humans are remarkably dependent on the visual system to gain information about our surroundings. Consider how tentatively you walk from the light switch to your bed right after turning off the lights!

The visual system is complex and consists of several interacting anatomical structures. Here, we will describe the process of how photons of light from our surroundings become signals that the brain turns into representations of our surroundings.

Properties of Light

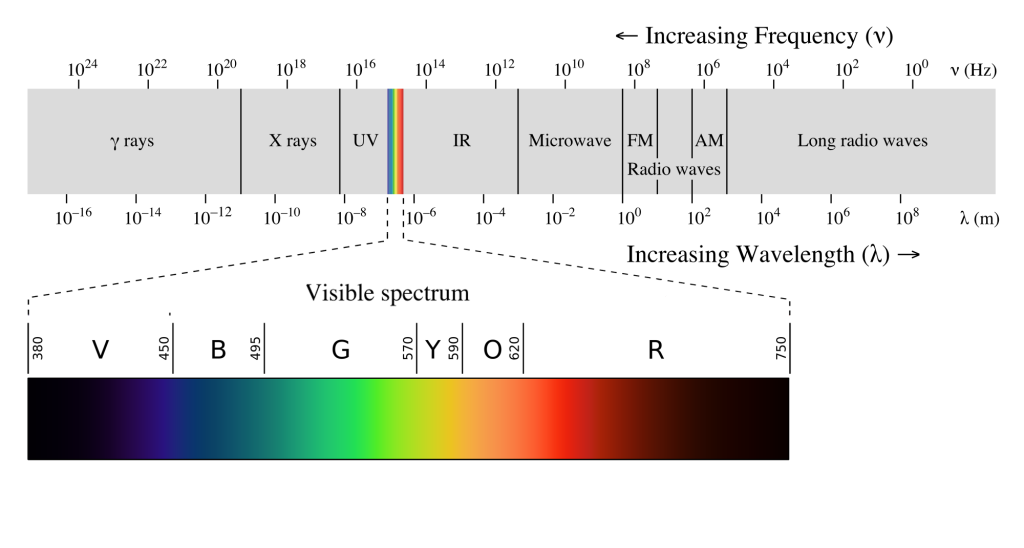

Visual sensation starts at the level of the eye. The eye is an organ that has evolved to capture photons, the elementary particle of light. Photons are unusual because they behave as both particles and as waves, but neuroscientists mostly focus on the wave-like properties. Because photons travel as waves, they oscillate at different frequencies. The frequency at which a photon oscillates is directly related to the color that we perceive.

The human visual system is capable of seeing light in a very narrow range of frequencies on the electromagnetic spectrum. On the short end, 400 nm wavelengths are observed as violet, while on the long end, 700 nm wavelengths are red. Ultraviolet light oscillates at a wavelength shorter than 400 nm, while infrared light oscillates at a wavelength longer than 700 nm. Neither ultraviolet nor infrared light can be detected with our eyes.

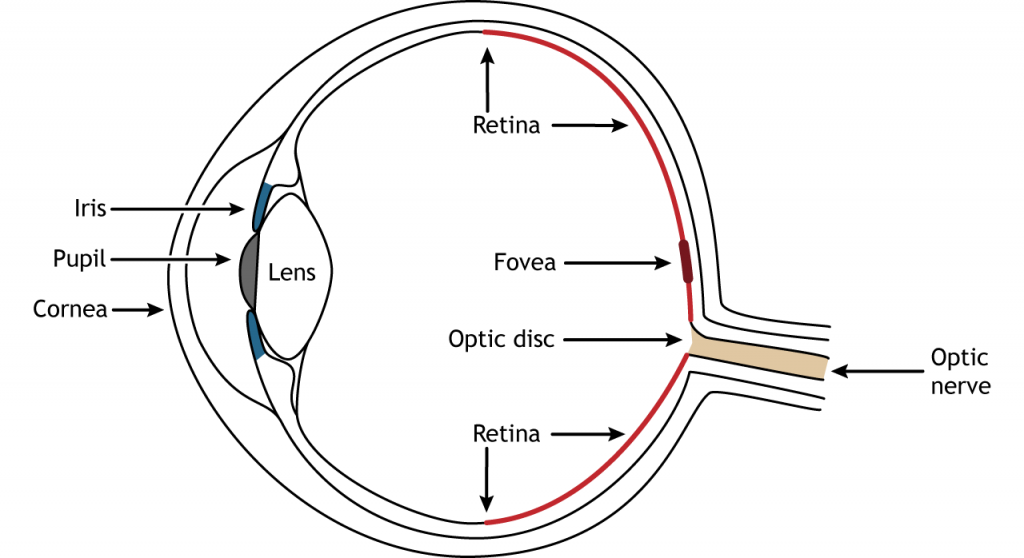

Anatomy of the Eye

Photons pass through several anatomical structures before the nervous system processes and interprets them. The front of the eye consists of the cornea, pupil, iris, and lens. The cornea is the transparent, external part of the eye. The cornea refracts, or bends, the incoming rays of light so that they converge precisely at the retina, the posterior most part of the eye. If the light rays fail to properly converge, a person would be near-sighted or far-sighted, and this would result in blurry vision. Glasses or contact lenses bend light before it reaches the cornea to compensate the cornea’s shape.

After passing through the cornea, light enters through a hole in the opening in the iris at the center of the eye called the pupil. The iris is the colored portion of the eye that surrounds the pupil and along with local muscles that can control the size of the pupil to allow for an appropriate amount of light to enter the eye. The diameter of the pupil can change depending on ambient light conditions. In the dark, the pupil dilates, or gets bigger, which allows the eye to capture more light. In bright conditions, the pupils constricts, or gets smaller, which decreases the amount of light that enters the eye.

The next structure that light passes through is the lens. The lens is located behind the pupil and iris. Like the cornea, the lens refracts light so that the rays converge on the retina. Proper focusing requires the lens to stretch or relax, a process called accommodation. A circular muscle that surrounds the lens, called the ciliary muscle, changes the shape of the lens depending on the distance of the object of focus.

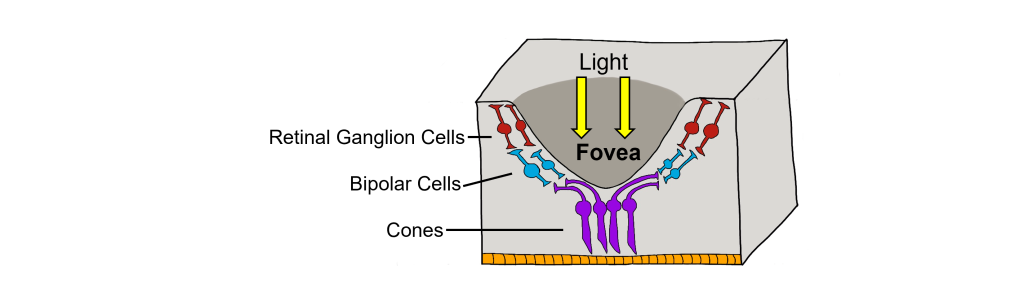

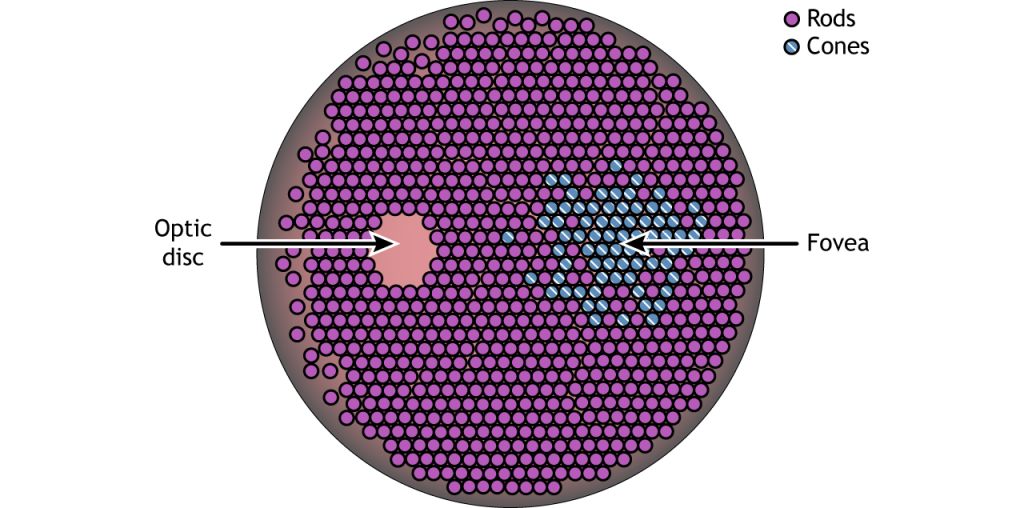

The retina is the light-sensitive region in the back of the eye where the photoreceptors, the specialized cells that respond to light, are located. The retina covers the entire back portion of the eye, so it’s shaped like a bowl. In the middle of the bowl is the fovea, the region of highest visual acuity, meaning the area that can form the sharpest images. The optic nerve projects to the brain from the back of the eye, carrying information from the retinal cells. Where the optic nerve leaves, there are no photoreceptors since the axons from the neurons are coming together. This region is called the optic disc and is the location of the blind spot in our visual field.

Retinal Cells

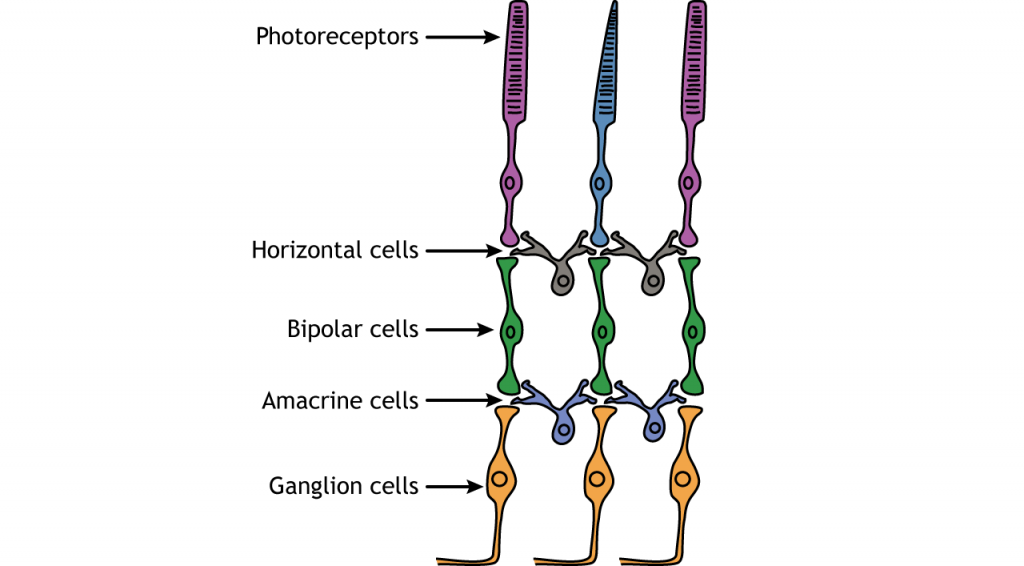

In addition to the photoreceptors, there are four other cell types in the retina. The photoreceptors synapse on bipolar cells, and the bipolar cells synapse on the ganglion cells. Horizontal and amacrine cells allow for communication laterally between the neuron layers.

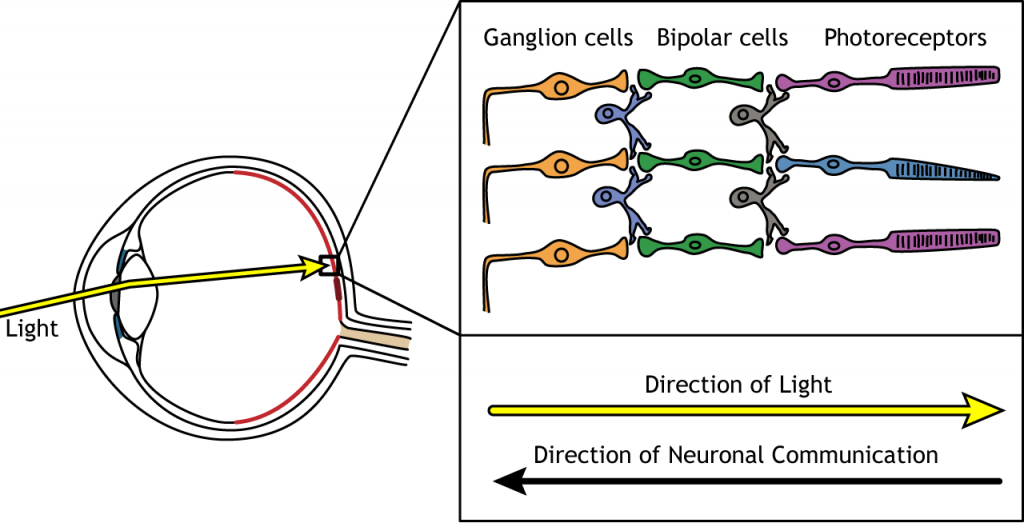

Direction of Information

When light enters the eye and strikes the retina, it must pass through all the neuronal cell layers before reaching and activating the photoreceptors. The photoreceptors then initiate the synaptic communication back toward the ganglion cells.

Photoreceptors

Photoreceptors are the first cells in the neuronal visual perception pathway. The photoreceptors are the specialized receptors that respond to light. They are the cells that detect photons of light and convert them into neurotransmitter release, a process called phototransduction.

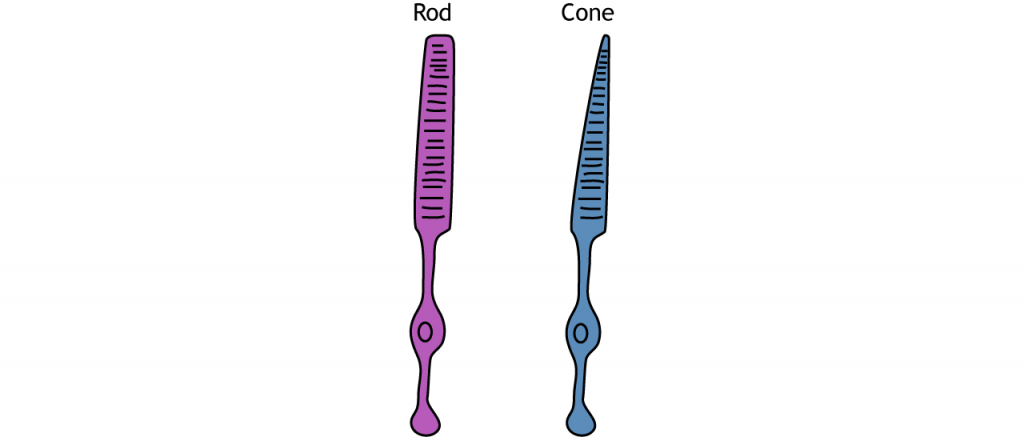

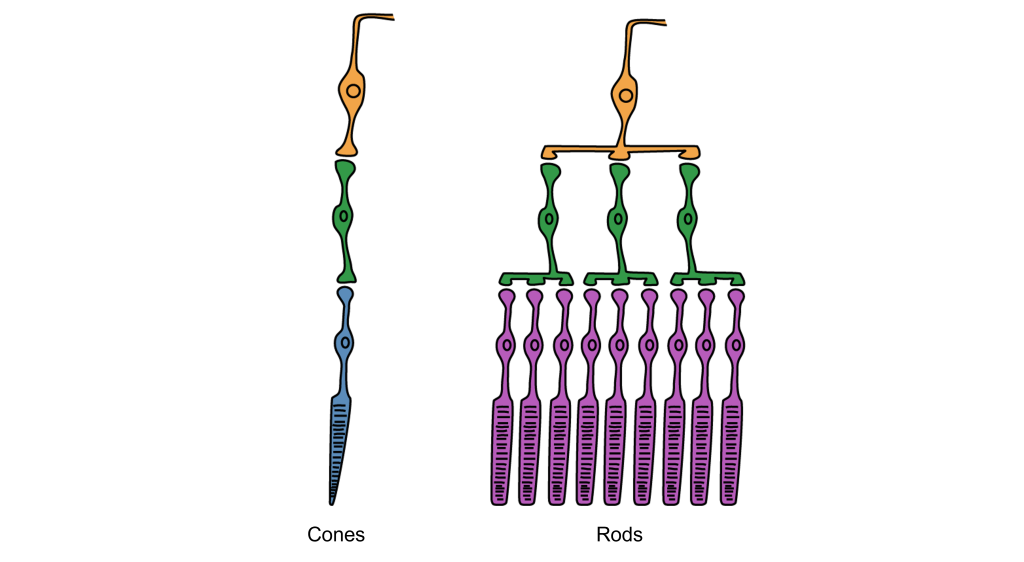

Morphologically, photoreceptor cells have two parts, an outer segment and inner segment. The outer segment contains stacks of membranous disks bounded within the neuronal membrane. These membranous disks contain molecules called photopigments, which are the light-sensing components of the photoreceptors. Hundreds of billions of these photopigments can be found in a single photoreceptor cell. The inner segment contains the nucleus and other organelles. Extending from the inner segment is the axon terminal.

Photoreceptors are classified into two categories, named because of their appearance and shape: rods and cones. Rod photoreceptors have a long cylindrical outer segment that holds many membranous disks. The presence of more membranous disks means that rod photoreceptors contain more photopigments and thus are capable of greater light sensitivity.

Cone photoreceptors have a short, tapered c, and cylindrical outer segment that holds fewer membranous disks than rod photoreceptors. The presence of less membranous disks means that cone photoreceptors contain less photopigments and thus are not as sensitive to light as rod photoreceptors. Cone photoreceptors are responsible for processing our sensation of color (the easiest way to remember this is cones = color). The typical human has three different types of cone photoreceptors cells, with each of these three types tuned to specific wavelengths of light. The short wavelength cones (S-cones) respond most robustly to 420 nm violet light. The middle wavelength cones (M-cones) exhibit peak responding at 530 nm green light, and the long wavelength cones (L-cones) are most responsive in 560 nm red light. Each of these cones is activated by other wavelengths of light too, but to a lesser degree. Every color on the visible spectrum is represented by some combination of activity of these three cone photoreceptors.

The idea that we have two different cellular populations and circuits that are used in visual perception is called the duplicity theory of vision and is our current understanding of how the visual system perceives light. It suggests that both the rods and cones are used simultaneously and complement each other. The photopic vision, uses cone photoreceptors of the retina, and is responsible for high-acuity sight and color vision in daytime. Its counterpart, called scotopic vision, uses rod photoreceptors and is best for seeing in low-light conditions, such as at night. Both rods and cones are used for mesopic vision, when there are intermediate lighting conditions, such as indoor lighting or outdoor traffic lighting at night.

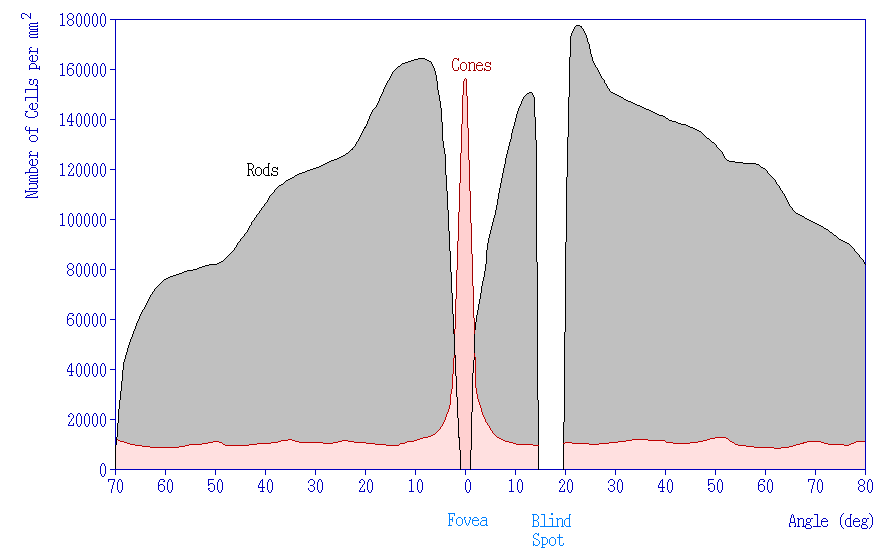

Photoreceptor Density

In addition to having different visual functions, the rods and cones are also distributed across the retina in different densities. Visual information from our peripheral vision is generally detected by our rod cells, which are most densely concentrated outside the fovea. Cone photoreceptor cells allow for high-acuity vision. They are most densely packed at the fovea, corresponding to the very center of your visual field. Despite being the cell population that we use for our best vision, cone cells make up the minority of photoreceptors in the human retina, outnumbered by about 20-times more rod cells.

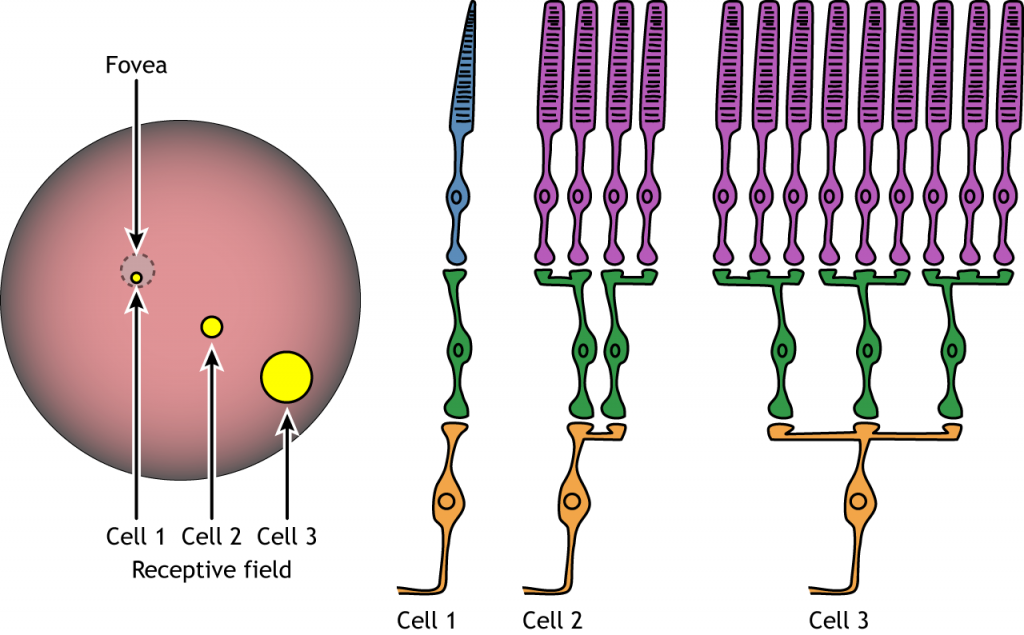

Synaptic Convergence of Photoreceptors

Rod cells are organized to have high synaptic convergence, where several rod cells (up to 30) feed into a single downstream route of communication (the bipolar cells, to be specific). An advantage of a high-convergence network is the ability to add many small signals together to create a seemingly larger signal. Consider stargazing at night, for example. Each rod is able to detect low levels of light, but signals from multiple rod cells, when summed together, allows you to recognize faint light sources such as a star. A disadvantage of this type of organization is that it is difficult to identify exactly which photoreceptor is activated by the incoming light, which is why accuracy is poor when seeing stimuli in our peripheral vision. This is one of the reasons that we cannot actually read text in our peripheral vision or see the distinct edges of a star. Rod photoreceptors are maximally active in low-light conditions.

Unlike rod cells, cone cells have very low synaptic convergence. In fact, at the point of highest visual acuity, a single cone photoreceptor communicates with a single pathway to the brain. The signaling from low-convergence networks is not additive, so they are less effective at low light conditions. However, because of this low-convergence organization, cone cells are highly effective at precisely identifying the location of incoming light.

Retina: Fovea and Optic Disk

The retina is not completely uniform across the entire back of the eye. There are a few spots of particular interest along the retina where the cellular morphology is different: the fovea and the optic disk.

There are two cellular differences that explain why the fovea is the site of our best visual acuity. For one, the neurons found at the fovea are “swept” away from the center, which explains why the fovea looks like a pit. Cell membranes are made up mostly of lipids, which distort the passage of light. Because there are fewer cell bodies present here, the photons of light that reach the fovea are not refracted by the presence of other neurons. Secondly, the distribution of photoreceptors at the fovea heavily leans toward cone type photoreceptors. Because the cone cells at the fovea exhibit low convergence, they are most accurately able to pinpoint the exact location of incoming light. On the other hand, most of the photoreceptors in the periphery are rod cells. With their high-convergence circuitry, the periphery of the retina is suited for detecting small amounts of light, though location and detail information is reduced.

Another anatomically interesting area of the retina is an elliptical spot called the optic disk. This is where the optic nerve exits the eye. At this part of the retina, there is an absence of photoreceptor cells. Because of this, we are unable to perceive light that falls onto the optic disk. This spot in our vision is called the blind spot.

Phototransduction

The photoreceptors are responsible for sensory transduction in the visual system, converting light into electrical signals in the neurons. For our purposes, to examine the function of the photoreceptors, we will A) focus on black and white light (not color vision) and B) assume the cells are moving from either an area of dark to an area of light or vice versa.

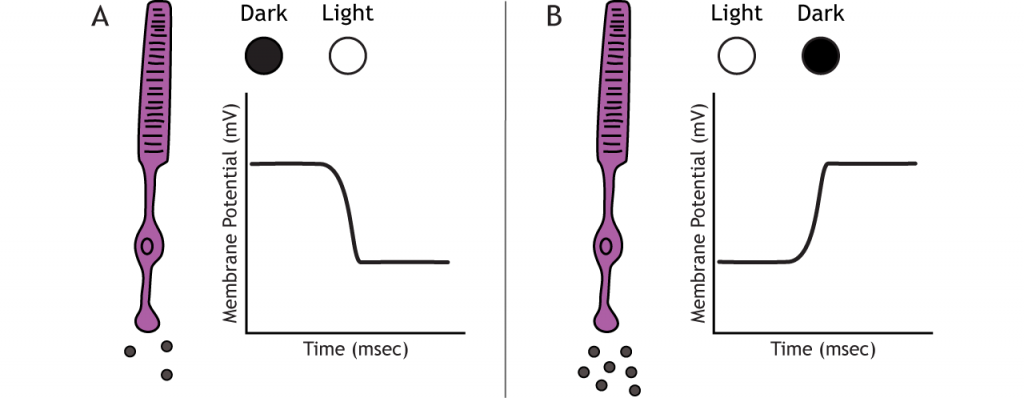

Photoreceptors do not fire action potentials; they respond to light changes with graded receptor potentials (depolarization or hyperpolarization). Despite this, the photoreceptors still release glutamate onto the bipolar cells. The amount of glutamate released changes along with the membrane potential, so a hyperpolarization will lead to less glutamate being released. Photoreceptors hyperpolarize in light and depolarize in dark. In the graphs used in this lesson, the starting membrane potential will depend on the initial lighting condition.

When the photoreceptor moves into the light, the cell hyperpolarizes. Light enters the eye, reaches the photoreceptors, and causes a conformational change in a special receptor protein called an opsin. The opsin receptor has a pre-bound chemical agonist called retinal. Together, the opsin + retinal makes up the photopigment rhodopsin.

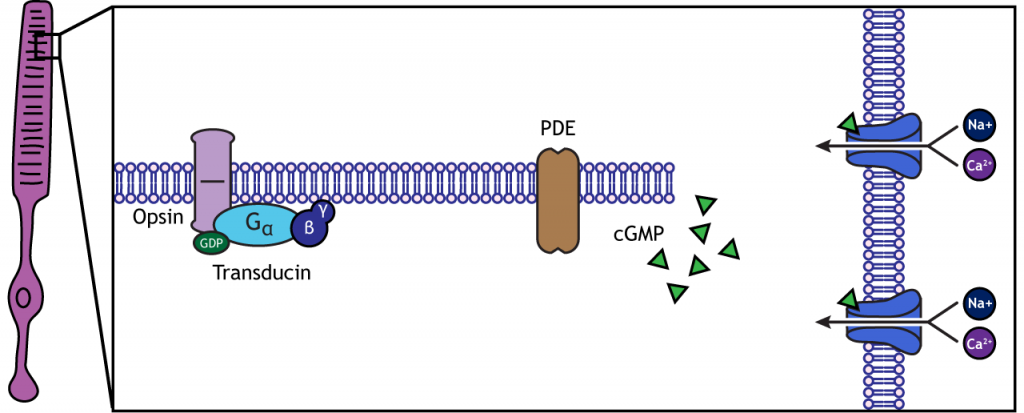

When rhodopsin absorbs light, it causes a conformational change in the pre-bound retinal, in a process called “bleaching”. The bleaching of rhodopsin activates an associated G-protein called transducin, which then activates an effector enzyme called phosphodiesterase (PDE). PDE breaks down cGMP in the cell to GMP. As a result, the cGMP-gated ion channels close. The decrease in cation flow into the cell causes the photoreceptor to hyperpolarize.

Animation 29.1. Light reaching the photoreceptor causes a conformational change in the opsin protein, which activates the G-protein transducing. Transducin activates phosphodiesterase (PDE), which converts cGMP to GMP. Without cGMP, the cation channels close, stopping the influx of positive ions. This results in a hyperpolarization of the cell. ‘Phototransduction’ by Casey Henley is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share-Alike (CC BY-NC-SA) 4.0 International License. View static image of animation.

In the dark, the photoreceptor has a membrane potential that is more depolarized than the “typical” neuron we examined in previous chapters; the photoreceptor membrane potential is approximately -40 mV.

Rhodopsin is not bleached, thus the associated G-protein, transducin, remains inactive. As a result, there is no activation of the PDE enzyme, and levels of cGMP within the cell remain high. cGMP binds to cGMP-gated sodium ion channels, causing them to open. The open cation channels allow the influx of sodium and calcium, which depolarize the cell in the dark.

Transmission of Information within Retina

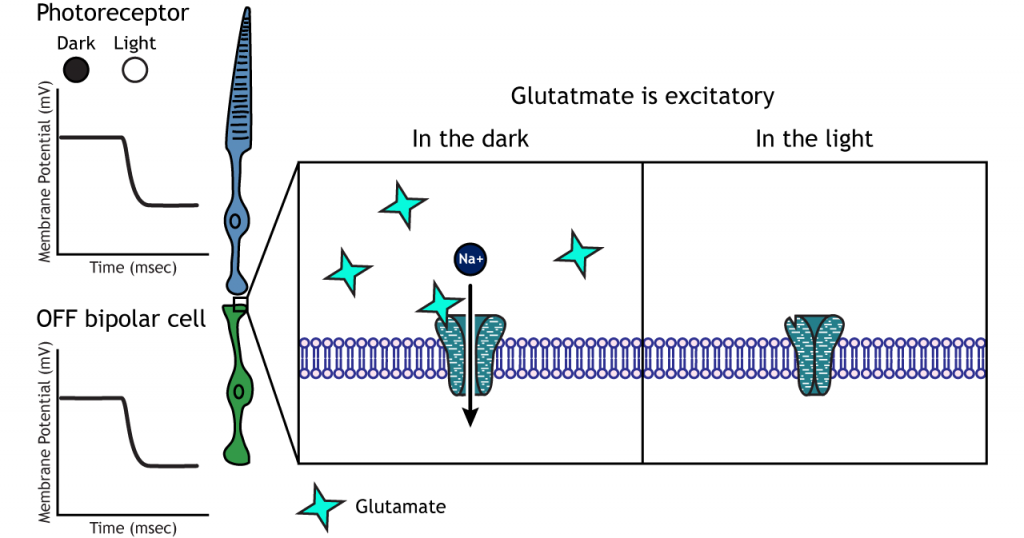

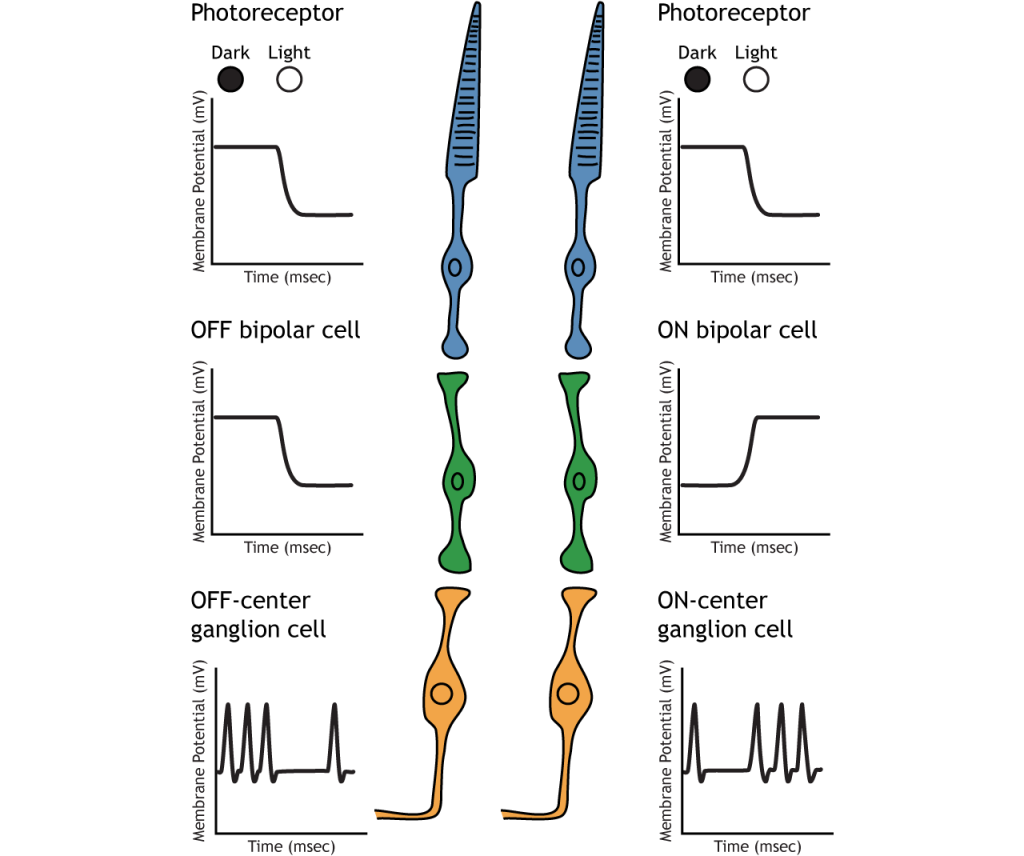

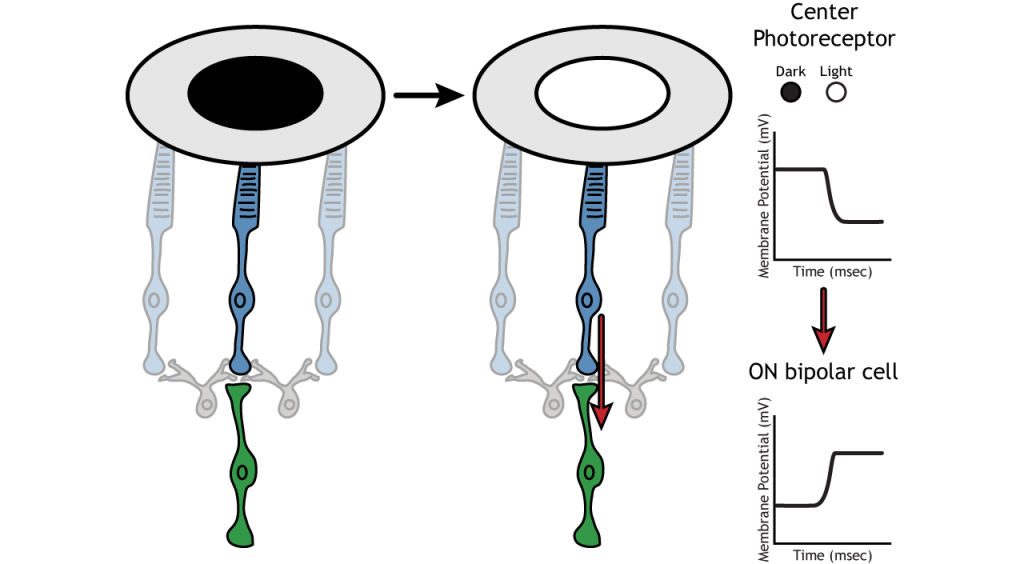

Photoreceptors synapse onto bipolar cells in the retina. There are two types of bipolar cells: OFF-center bipolar cells and ON-center bipolar cells. These cells respond in opposite ways to the glutamate released by the photoreceptors because they express different types of glutamate receptors. Like photoreceptors, the bipolar cells do not fire action potential and only respond with graded postsynaptic potentials.

OFF-center Bipolar Cells

In OFF-center bipolar cells, the glutamate released by the photoreceptor is excitatory. OFF-center bipolar cells express ionotropic glutamate receptors. In the dark, the photoreceptor is depolarized, and thus releases more glutamate. The glutamate released by the photoreceptor activates the ionotropic receptors, and sodium can flow into the cell, depolarizing the membrane potential. In the light, the photoreceptor is hyperpolarized, and thus does not release glutamate. This lack of glutamate causes the ionotropic receptors to close, preventing sodium influx, hyperpolarizing the membrane potential of the OFF-center bipolar cell. One way to remember this is that OFF-center bipolar cells are excited by the dark (when the lights are OFF).

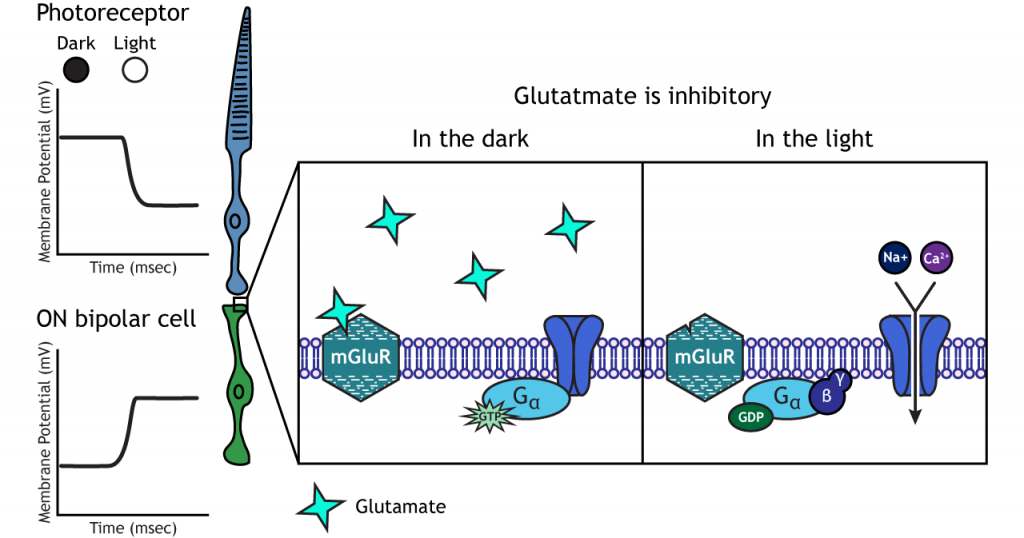

ON-center Bipolar Cells

In ON-center bipolar cells, the glutamate released by the photoreceptor is inhibitory. ON-center bipolar cells express metabotropic glutamate receptors. In the dark, the photoreceptor is depolarized, and thus releases more glutamate. The glutamate released by the photoreceptor binds to the metabotropic receptors on ON-center bipolar cells, and the G-proteins close cation channels in the membrane, stopping the influx of sodium and calcium, hyperpolarizing the membrane potential. In the light, the photoreceptor is hyperpolarized, and thus does not release glutamate. The absence of glutamate results in the ion channels being open and allowing cation influx, depolarizing the membrane potential. You can remember that ON-center bipolar cells are excited by the light (when the lights are ON).

Retinal Ganglion Cells

Retinal ganglion cells are the third and last cell type that directly conveys visual sensory information, receiving inputs from the bipolar cells. OFF-center and ON-center bipolar cells synapse on OFF-center and ON-center ganglion cells, respectively. The axons of the retinal ganglion cells bundle together and form the optic nerve, which then exits the eye through the optic disk. Retinal ganglion cells are the only cell type to send information out of the retina, and they are also the only cell that fires action potentials. The ganglion cells fire in all lighting conditions, but it is the relative firing rate that encodes information about light. A move from dark to light will cause OFF-center ganglion cells to decrease their firing rate and ON-center ganglion cells to increase their firing rate.

Receptive Fields

Each bipolar and ganglion cell responds to light stimulus in a specific area of the retina. This region of retina is the cell’s receptive field. Receptive fields in the retina are circular.

Size of the receptive field can vary. The fovea has smaller receptive fields than the peripheral retina. The size depends on the number of photoreceptors that synapse on a given bipolar cell and the number of bipolar cells that synapse on a given ganglion cell, also called the amount of convergence.

Receptive Field Example

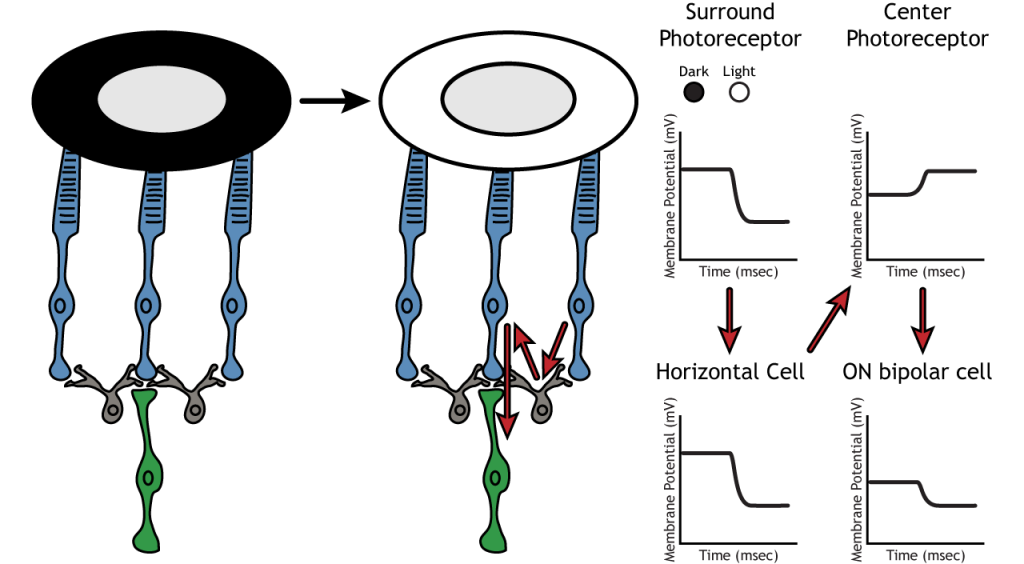

Let’s use an example of an ON-center bipolar cell to look at the structure of receptive fields in the retina. The bipolar and retinal ganglion cell receptive fields are divided into two regions: the center and the surround. The center of the receptive field is a result of direct innervation between the photoreceptors, bipolar cells, and ganglion cells. If a light spot covers the center of the receptive field, the ON-center bipolar cell would depolarize, as discussed above; the light hits the photoreceptor, it hyperpolarizes, decreasing glutamate release. Less glutamate leads to less inhibition of the ON bipolar cell, and it depolarizes.

The surround portion of the receptive field is a result of indirect communication among the retinal neurons via horizontal and amacrine cells. The surround has an opposing effect on the bipolar or ganglion cell compared to the effect of the center region. That is to say, that the center and surround of the receptive field are opposite to each other. So, an ON-center bipolar or ganglion cell, can also be referred to as an “ON-center OFF-surround cell”, and an OFF-center bipolar or ganglion cell can also be referred to as an “OFF-center ON-surround cell”.

Therefore, if light covers the surround portion, the ON-center bipolar cell would respond by hyperpolarizing. The light would cause the photoreceptor in the surround to hyperpolarize. This would cause the horizontal cell to also hyperpolarize. Horizontal cells have inhibitory synaptic effects, so a hyperpolarization in the horizontal cell would lead to a depolarization in the center photoreceptor. The center photoreceptor would then cause a hyperpolarization in the ON-center bipolar cell. These effects mimic those seen when the center is in dark. So, even though the center photoreceptor is not directly experiencing a change in lighting conditions, the neurons respond as if they were moving toward dark.

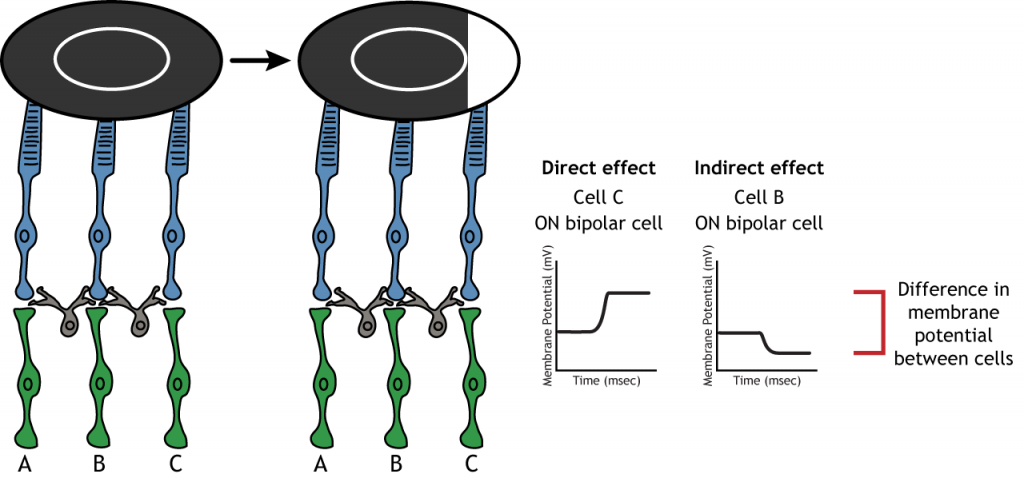

Lateral Inhibition

The center-surround structure of the receptive field is critical for lateral inhibition to occur. Lateral inhibition is the ability of the sensory systems to enhance the perception of edges of stimuli. It is important to note that the photoreceptors that are in the surround of one bipolar cell would also be in the center of a different bipolar cell. This leads to a direct synaptic effect on one bipolar cell while also having an indirect effect on another bipolar cell.

Although some of the images used here will simplify the receptive field to one cell in the center and a couple in the surround, it is important to remember that photoreceptors cover the entire surface of the retina, and the receptive field is two-dimensional. Depending on the level of convergence on the bipolar and ganglion cells, receptive fields can contain many photoreceptors.

Key Takeaways

- Photoreceptors and bipolar cells do not fire action potentials

- Photoreceptors hyperpolarize in the light

- ON bipolar cells express inhibitory metabotropic glutamate receptors

- OFF bipolar cells express excitatory ionotropic glutamate receptors

- Receptive fields are circular, have a center and a surround, and vary in size

- Receptive field structure allows for lateral inhibition to occur

Test Yourself!

Additional Review

- Compare and contrast rods and cones.

- Compare and contrast the fovea and the optic disc.

Attributions

Portions of this chapter were remixed and revised from the following sources:

- Foundations of Neuroscience by Casey Henley. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

- Open Neuroscience Initiative by Austin Lim. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.