18 Neurotransmitters: Atypical Neurotransmitters

Learning Objectives

Know the feature and properties of the following atypical neurotransmitters

- Neuropeptides

- Endocannabinoids

- Nitric Oxide

Although we generally think of neurotransmitters as neurochemicals that function as described in the previous chapters, there are a few atypical neurotransmitters that don’t quite fit the mold of the other chemical signals.

Neuropeptides

Neuropeptides are a class of large signaling molecules that some neurons synthesize. Neuropeptides are different from the traditional neurotransmitters because of their chemical size. Neuropeptides are a short string of amino acids and are known to have a wide range of effects from emotions to pain perception. Unlike small molecule neurotransmitters, neuropeptides are synthesized in the cell body and transported to the axon terminal.

Synthesis and Storage

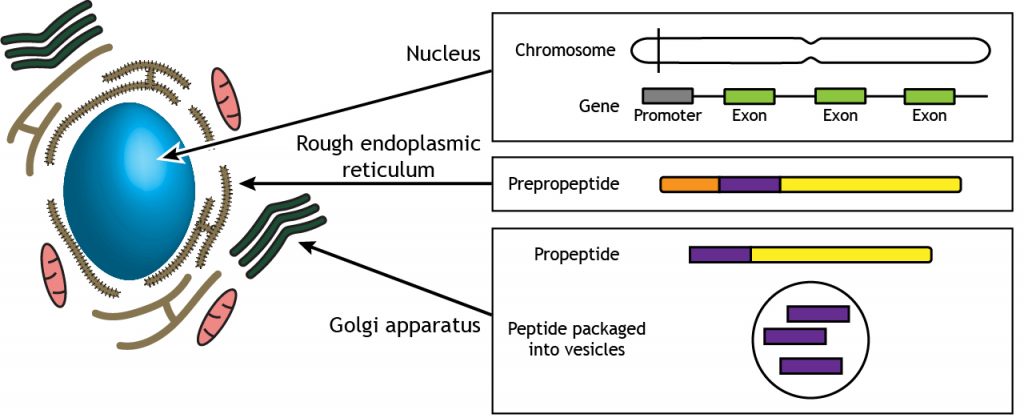

Like other proteins, neuropeptides are synthesized from mRNA into peptide chains made from amino acids. In most cases, a larger precursor molecule called the prepropeptide is translated into the original amino acid sequence in the rough endoplasmic reticulum. The prepropeptide is processed further to the propeptide stage. The remaining processing and packaging of the final neuropeptide into a vesicle occurs in the Golgi apparatus.

Monoamines like dopamine, norepinephrine, or serotonin have a molecular weight around 150-200, while one of the smaller neuropeptides, enkephalin, has a molecular weight of 570. One of the largest neuropeptides, dynorphin, has a molecular weight greater than 2,000. Because of their large size, neuropeptides have to be packaged in dense core vesicles very close to the site of production near the nucleus, rather than in clear vesicles right at the terminal. These large vesicles must then move from the soma to the terminal.

Neuropeptide synthesis occurs in the cell body. Each neuropeptide is encoded by a gene on the DNA located in the nucleus. mRNA is translated into an amino acid sequence for a precursor molecule called a prepropeptide in the rough endoplasmic reticulum. Further processing and packaging of the neuropeptide into vesicles occurs in the Golgi apparatus. ‘Neuropeptide Synthesis’ by Casey Henley is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share-Alike (CC BY-NC-SA) 4.0 International License.

Axonal Transport of Neuropeptides

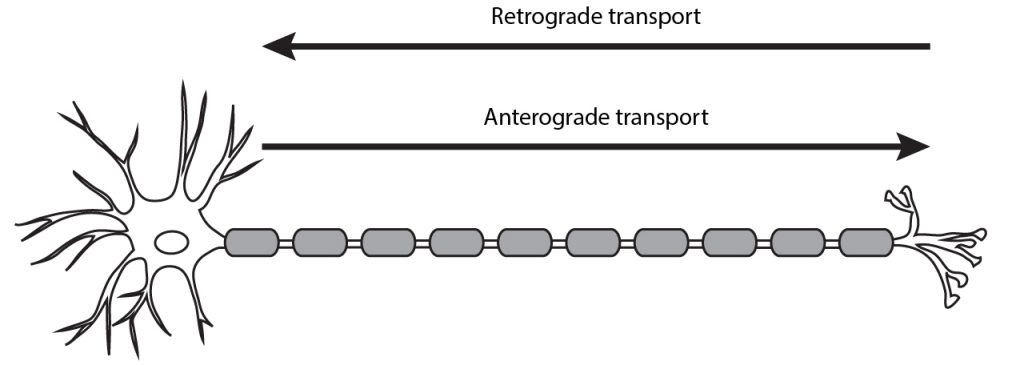

The packaged peptides need to be transported to the presynaptic terminals to be released into the synaptic cleft. Organelles, vesicles, and proteins can be moved from the cell body to the terminal via anterograde transport or from the terminal to the cell body via retrograde transport. Anterograde transport can be either fast or slow.

The packaged neuropeptides are transported to the synaptic terminals via fast anterograde axonal transport mechanisms.

Dense Core Synaptic Vesicles.

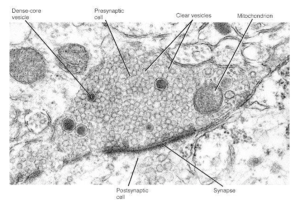

Neuropeptides are stored in synaptic vesicles, just as the classical small neurotransmitters, but their vesicles are usually larger and fewer in number. In electron micrographs, the peptide vesicles have a dark inside, and thus are called dense-core vesicles (see below).

These large, dense-core vesicles are observed intermixed with the smaller clear-core vesicles that contain the small neurotransmitters and are usually situated farther back from the presynaptic membrane. They are believed to release their contents through exocytosis, but the steps leading up to this are not as well understood as they are for clear vesicles. Ca2+ may also be the signal, but must diffuse farther into the terminal to initiate neuropeptide release. This remains an active area of research.

Neuropeptide Receptors

Neuropeptides such as enkephalin and dynorphin are agonists at a class of receptors called the opioid receptors. These opioid receptors fall into four main types. The three classical opioid receptors are named using Greek letters: δ (delta), μ (mu), and κ (kappa); the fourth class is the nociceptin receptor. All of these receptors are inhibitory metabotropic receptors which signal using the Gαi protein. These receptors are expressed in several brain areas, but expression is particularly heavy in the periaqueductal gray, a midbrain area that functions to inhibit the sensation of pain. Drugs that activate the opioid receptors, like morphine, oxycontin, or fentanyl, are the most effective clinical treatments that we know of for acute pain. Unfortunately, these same drugs also represent a tremendous health risk, as opioid drugs can be lethal in overdose and have a high risk of substance use disorder.

Endocannabinoids

Endocannabinoids are endogenous lipid neurotransmitters that are a bit unusual compared to the other neurotransmitters that we have covered. First, they signal in a retrograde manner. This means that the endocannabinoid neurotransmitters are released by the postsynaptic cell and bind to receptors on the presynaptic cell. Additionally, endocannabinoids are not packaged into vesicles and released by fusion with the cell membrane.

Instead, when the activation of receptors in the postsynaptic cell leads to an influx of calcium ions (Ca2+), the local increase in Ca2+ concentration within the postsynaptic cell triggers the cell to synthesize endocannabinoids. Again, these neurotransmitters are not stored in vesicles like the other neurotransmitters that have been discussed. Instead, these lipid neurotransmitters are made on demand, or synthesized ‘de novo’. After synthesis the endocannabinoids are released from the postsynaptic cell through special membrane transporters. The two most well-characterized eCBs in humans are called 2-Arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and Anandamide (ANA).

The endocannabinoids bind to one of two receptors, CB1 or CB2. Both receptor types are inhibitory metabotropic receptors that are located on the presynaptic cell and coupled to Gαi. Generally, CB1 receptors are found in the nervous system, while the CB2 receptors are found elsewhere in the body, such as in the immune system. Activity of the metabotropic CB1 receptors causes presynaptic calcium channels to close, reducing the concentration of calcium in the presynaptic cell, and thus decreasing the amount of neurotransmitter released by the presynaptic cell.

The endocannabinoid system is widely used by various systems in the body. It is estimated that endocannabinoid receptors are the most abundant GPCRs in the whole body. These substances were named because they are endogenous chemicals that are functionally similar to compounds found in plants of the genus Cannabis, also known as marijuana. The principal ingredient in Marijuana is Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which produces its psychoactive effects by activating CB receptors.

Gaseous Neurotransmitters: Nitric Oxide

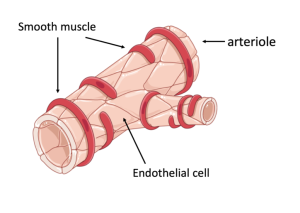

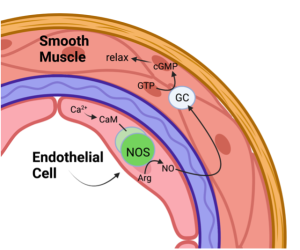

Nitric oxide was first discovered outside the nervous system. It was shown to deliver a signal from the endothelial cells that line tiny blood vessels (arterioles) to the smooth muscle in the walls of these blood vessels. The smooth muscle encircles the arterioles (think of tiny donuts around a straw, unless you are hungry, then think of something else). When the nitric oxide enters these smooth muscle cells, they relax, making the circles larger and opening up the blood vessel. This dilation allows more blood to flow to the tissue being supplied by the arteriole.

(Left) Diagram of a blood vessel (e.g. an arteriole) wrapped by smooth muscle that constrict or dilate the vessel, changing the amount of blood flow. (Right) A diagram of what happens in the cells that form the wall of a blood vessel. The inner layer of cells (endothelial cells) synthesize NO which diffuses to the smooth muscle and activates chemical reactions that lead to relaxation of the smooth muscle and dilation of the blood vessel.

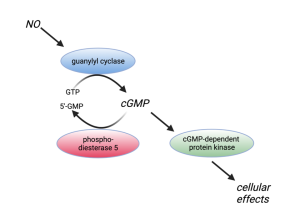

An ever-present reminder on TV commercials, the drug Viagra which alleviates male erectile dysfunction, works by prolonging the life of the second messenger produced by nitric oxide. As a result, the blood vessel will remain dilated longer, extending the duration of the increased blood to flow to the corpus cavernosum in the penis. Hence, a larger and longer erection.

Shortly after nitric oxide was discovered in the circulatory system, it was found to be a signaling molecule at synapses in the brain. It is quite different from the classical neurotransmitters because it can’t be packaged inside synaptic vesicles. Even though it is slightly polar, it is too small to be dissuaded from passing between the fatty acid tails of phospholipids. Thus, it cannot be packaged and released at a later time. Instead, nitric oxide must be synthesized when it is required. The enzyme that synthesizes nitric oxide, which is cleverly named nitric oxide synthase (NOS), catalyzes the production of nitric oxide from the amino acid L-arginine. There are four known subtypes of NOS: endothelial (eNOS), inducible (iNOS), bacterial (bNOS) and neuronal (nNOS). The neuronal and endothelial forms are activated by Ca2+, which first binds to a ubiquitous protein called calmodulin, and then the calcium-calmodulin complex activates the synthesis of NO. NO immediately diffuses away from where it is synthesized and normally diffuses out of the cell in which it is made and makes its way to nearby target cells. Since NO is unstable, it degrades rapidly, with a half-life measured in seconds. This limits NO’s effects to cells that are relatively close (e.g. the target cell is often just across the synaptic gap).

The most common way that NO has an effect in the target cell is by activating an enzyme called guanylyl cyclase (GC). GC catalyzes the conversion of GTP to cGMP. This is analogous to the reaction we discussed in the previous chapter in which adenylate cyclase converts ATP to cAMP. As happens in this case, the cGMP activates a protein kinase (called cGMP-dependent protein kinase) which phosphorylates a target protein and thereby changes the activity of the target cell (e.g. NO increases the activity of postsynaptic receptors and/or increases the release of glutamate during LTP).

cGMP, like all second messengers, must eventually be degraded or else the signal will persist forever. cGMP is converted to 5’-GMP by an enzyme called a phosphodiesterase. This is the step Viagra blocks as mentioned previously.

Other gaseous molecules, such as CO and H2S (yes, the gas that smells liken rotten eggs), have also been found to act as signaling molecules; however, they do not appear to be nearly as ubiquitous as NO.

Key Takeaways

- Neuropeptides are proteins that are synthesized in the cell body and are transported in vesicles to the axon terminal

- Endocannabinoids are lipid neurotransmitters that use retrograde signaling. They are synthesized and released by the postsynaptic cell and bind to metabotropic CB1 receptors on the presynaptic cell to alter neurotransmitter release.

- Nitric oxide is a gas neurotransmitter that is not stored in vesicles but instead is made on demand. As a gas, nitric oxide can easily cross the phospholipid bilayer and bind to intracellular receptors.

Test Yourself!

Attributions

Portions of this chapter were remixed and revised from the following sources:

- Foundations of Neuroscience by Casey Henley. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

- Open Neuroscience Initiative by Austin Lim. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Media Attributions

- Private: ElectronMicrograph_C6

- Private: Arteriole_C6

- Private: EndothelialCell_C6

- Private: GCEnzymeCycle_C6

Movement from the cell body to the axon terminals

Movement from the axon terminals toward the cell body

made within the body

Postsynaptic receptors in which neurotransmitters bind and cause the activation of an associated G-protein and cell signaling cascades. The affected ion channel and receptor are found on different transmembrane proteins..