5 The Plasma Membrane – the most important organelle

Learning Objectives

Understand the structure and function of the cell membrane

- The properties of water and the significance of these properties.

- The role of phospholipids in the structure and function of the lipid bilayer.

- The structure and function of membrane proteins: integral vs. peripheral membrane proteins

- Ion channels

- Membrane transporters

- Membrane pumps

- Neurotransmitter receptors

- Components of the cytoskeleton

The plasma membrane refers to the membrane that defines the boundaries of the cell. It separates the inside (cytoplasm) from the outside (extracellular environment). It may not be obvious, but the plasma membrane is actually considered an organelle. In fact, to neuroscientists, it is the most important organelle of a neuron. Its properties support and define the function of neurons more so than any of the other organelles (mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, nucleus etc.). In this chapter, we will discuss the structure and function of membranes, with an emphasis on the outer plasma membrane. Before we get to that, we first need to discuss water.

Water – you either love it or you hate it

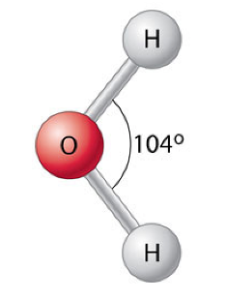

You have probably known since early in your childhood that water is made of H-two-O. But, what does that mean and why is it important? A water molecule contains one atom of Oxygen, which forms covalent bonds with two atoms of Hydrogen. For reasons that are beyond our scope, these bonds are constrained so that they form an angle of 104.5o, as shown to the right.

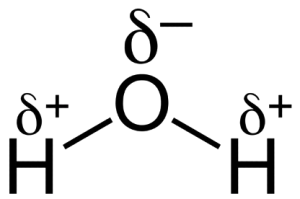

The other important feature of these bonds is that Oxygen and Hydrogen do not share the electrons in the bond equally. Just a quick reminder: in covalent bonds, the two atoms share some electrons. In what is called a single bond, which we have here, two electrons are shared. That is, these two electrons are just as much part of the oxygen atom as the hydrogen atom, which is why the two atoms are connected and can be referred to as a molecule (a molecule is a collection of two or more atoms connected by covalent bonds). In some single bonds, these two electrons are shared equally. The bond between two Carbon atoms is a good example of this. In other cases, the shared electrons are attracted more strongly to one of the two atoms (technically, their nuclei). In the case of water, oxygen has a stronger attraction to the electrons than hydrogen has. As a result, the electrons spend more of their time around the oxygen than the hydrogen. This creates what we call “partial” negativity. If an electron was all by itself, or if an atom had one more electron than protons (we call this an ion), it would have a charge of -1. In the case of water, we say that the oxygen and hydrogen have partial charge. The partial charge, which we symbolize with the Greek letter δ (delta) is approximately 1/20th of a full charge. For the hydrogen, it is δ+ and for the oxygen it is δ–. This means that if you could walk around a water molecule with some sort of nano charge detector, your meter would pick up a slight positive charge when it was around the hydrogen and a slight negative charge when around the oxygen.

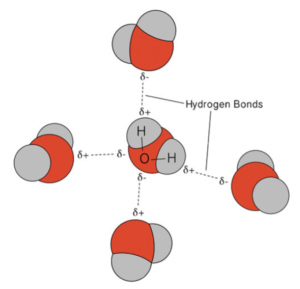

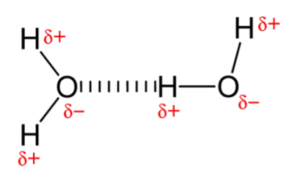

Now, lest you think this is all just arcane chemistry that has no relevance to your life, let me say that this property of water – more than just about anything else – is responsible for life. This is why astronomers are always keen to know whether planets contain, or may have contained in the past, water. Why is that? Because even though those partial charges are tiny, they still act like charge and attract or repel each other (remember, opposites attract, like repel). If there are a large number of molecules interacting like this, the overall effect can be significant. In a beaker that contains just water, the individual water molecules will tend to line up with their oxygen atoms surrounded by the hydrogen atoms of neighboring water molecules and vice versa (hydrogen surrounded by oxygen from neighboring water molecules).

These interactions between the oxygens and hydrogens from different molecules are called “hydrogen bonds.” Although each hydrogen bond is weak, by comparison to the attraction between atoms in a covalent bond, collectively they make a difference, a big difference. Hydrogen bonding between water molecules is responsible for water’s unique and life-creating properties. For example, the hydrogen bonds in water give it its relatively high boiling point, 212°F. In contrast, hydrogen sulfide (H2S), which is very similar to water in structure, boils at -76°F. Why so much lower than water? Because, H2S has minimal hydrogen bonding. This explains why you are unlikely to come across liquid H2S on earth (it all boils into the gas phase). If you could snap you finger and convert all of the H2O on earth to H2S, everything (including ourselves) would instantly boil. (NOTE: If you think you might have this ability, please do not snap your fingers.)

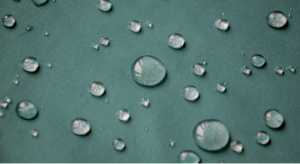

Another consequence of hydrogen bonding between water molecules relates to the kinds of molecules that dissolve in water. Molecules that disrupt hydrogen bonding do not dissolve. In fact, they repel water. Molecules like this are called hydrophobic, which literally means “water hating” or “water fearing”. Such molecules do not have any polarity; that is, they don’t have any charge. They are neither ions, which would have a full charge or two, or molecules that have partial charge across one or more of their covalent bonds. Lacking polarity, they cannot interact with water and instead just push water molecules away from each other, minimizing the total number of hydrogen bonds that can form. Such water-hating molecules just clump together, rather than mix with the water molecules (kind of like how boys clump together in a corner during a middle school dance rather than mixing with the girls.). To be fair, it is not just that non-polar molecules hate water, water also hates non-polar molecules. An example of this is how water beads up on your car’s windshield after getting waxed in the car wash. Rather than spread evenly over the window, the water molecules band together and minimize their interacting with the wax (and maximize their interaction with other water molecules).

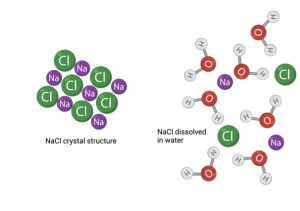

We will return to this property of hydrophobic molecules shortly when discussing cell membranes; however, we must also discuss the other class of molecules – hydrophilic, or water loving. As I said above, hydrophilic molecules have charge; they are either ions or have partial charge across one or more covalent bond. Either of these can interact with the partial charge across the bond between H and O in water molecules. Thus, hydrophilic molecules do not clump up to avoid interacting with water. In fact, just the opposite occurs. Hydrophilic molecules that are clumped together will break apart when added to water. Think of adding a sugar cube or crystals of salt (NaCl) to a glass of water. They immediately or perhaps with some encouragement from stirring, dissolve in the water. You can’t see them anymore because the individual molecules have dispersed among the water molecules. Rather than interacting with each other, they now interact with the water molecules. Water is called the universal solvent because just about anything that is polar (charged) will dissolve in it.

Before leaving this digression into chemistry, we need to consider one other class of molecules. Some molecules are hydrophilic on one side and hydrophilic on the other. They are called amphipathic. They hate both water and non-polar molecules. (Of course, you could also say they love both water and non-polar molecules.) Because of this split nature, they behave strangely. If they are dropped into a glass of water, they will arrange themselves to minimize the interaction between water and their hydrophobic parts and maximize the exposure of the hydrophilic parts to water. An important biological example of this relates to the folding of proteins. Proteins are inherently amphipathic. This property is one of the main drivers of the shape proteins take in the cell. They will fold up with the hydrophobic parts on the inside and the hydrophilic parts on the outside. As we will discuss shortly, the shape proteins take determines their function. This is just one example of many that reveal the fundamental relevance of water to the properties of life.

The Lipid Bilayer

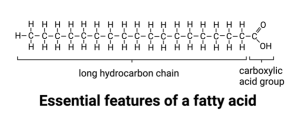

Our discussion of the cell membrane begins with the lipid bilayer. The term lipid refers to a class of organic compounds that are made up of fatty acids or their derivatives. Fatty acids consist of a chain of covalently linked carbon atoms with a carboxylic acid group on one end. What is important for our consideration is that the chain of hydrocarbons (each carbon in the chain is bound to one or more hydrogen atoms; thus, hydrocarbon) is hydrophobic.

You already know why this is, but just to review, the electrons that form the covalent bonds between the carbon atoms and between the carbon and hydrogen atoms are shared equally. There is no partial charge so we call them non-polar. In contrast, the carboxylic acid group on the end is polar. The covalent bonds between the oxygen and carbon and between the oxygen and hydrogen are polar. In fact, the hydrogen can be ripped off the oxygen by nearby water molecules that attract it away from the carboxylic acid oxygen. This results in a full charge on the oxygen.

You already know why this is, but just to review, the electrons that form the covalent bonds between the carbon atoms and between the carbon and hydrogen atoms are shared equally. There is no partial charge so we call them non-polar. In contrast, the carboxylic acid group on the end is polar. The covalent bonds between the oxygen and carbon and between the oxygen and hydrogen are polar. In fact, the hydrogen can be ripped off the oxygen by nearby water molecules that attract it away from the carboxylic acid oxygen. This results in a full charge on the oxygen.

You have probably already deduced that lipids are amphipathic. The hydrocarbon chain is hydrophobic and the terminal carboxylic acid is hydrophilic.

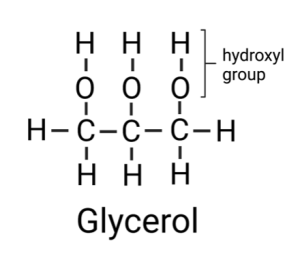

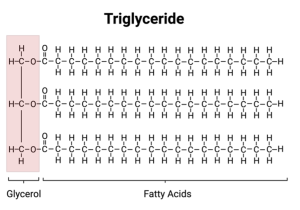

Most of the fat in your body is made up of molecules, called triglycerides, that contain three fatty acids attached to a molecule of glycerol. Glycerol is a chain of three carbons, with each carbon bound to one or more hydrogens and a hydroxyl group. A hydroxyl group is a hydrogen attached to an oxygen.

You have seen before what happens when oxygen binds to hydrogen – partial charge and polarity. Thus, a fat molecule is amphipathic and packs together in your fat cells to make sure you stay “well fed” even if there is no food around. (I prefer to emphasize the positive aspect of fat.)

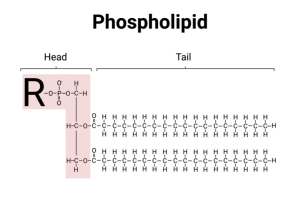

Phosphoglycerides (also called phospholipids) are the most common type of lipid in the cell membrane and are variants of the basic fat/lipid molecule. Rather than having three fatty acids, only two fatty acids are attached to glycerol. The remaining carbon on the glycerol backbone, on the end, is covalently attached to a phosphate group. Since phosphate is highly charged (it is ionic), this makes phospholipids strongly amphipathic. Usually, the phospholipids in the cell membrane also contain a larger molecule attached to the phosphate. This larger molecule, which is polar, is called the “head” of the phospholipid and the hydrocarbon chains of the fatty acids are called the “tail.”

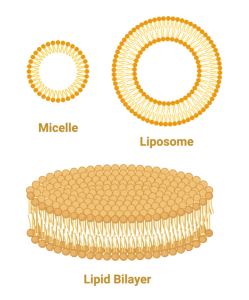

Because phosphoglycerides (phospholipids) are amphipathic, there are not many ways they can arrange themselves in water to feel comfortable. One way is to form a micelle. In this arrangement, the fatty acid tails all point inward with the heads pointing out. This minimizes the interaction of the tails with water and maximizes the interaction of the heads with water. Another arrangement which is equally stable is the lipid bilayer such as occurs in a liposome. In this case, the phospholipids line up side-by-side, but form two layers with the fatty acids of one layer pointing towards the fatty acids on the adjacent layer. Think of a bunch of people sleeping on a long bed with their feet pointing toward each other and their heads on the edge of the bed. Then, keep piling people on top with this same arrangement. While this would probably not be a comfortable way to sleep, this is a very stable arrangement for phospholipids, keeping the hydrophilic parts exposed to the water on either side of the bilayer and the hydrophobic parts buried inside.

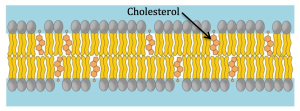

The lipid bilayer contains a few other molecules that are not phospholipids, such as cholesterol. Cholesterol has a completely different structure than phospholipids, but since it is also amphipathic, it arranges itself just like the phospholipids in the bilayer.

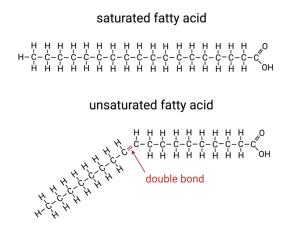

Lastly, one other feature I need to mention is that some of the fatty acids in phospholipids contain one or more double-bonds between the carbons. Instead of sharing two electrons, these carbons share four electrons with each other. For reasons that are beyond the scope of our discussion, double bonds are not as flexible as single bonds. Whereas carbons can freely rotate around a single bond, they are stuck in one arrangement when connected by a double bond. This double bond creates a kink in the hydrocarbon tails and interferes with the tight packing of the fatty acid tails. (Like if some of our sleepers lie on their side and bend one of their legs.)

Such fatty acids are called unsaturated because they are not saturated with hydrogens. Carbon atoms can only form four covalent bonds. If two of them form a double bond, that only leaves two remaining bonds each. One of these will be with an adjacent carbon in the chain, leaving only one to bind to a hydrogen. In contrast, carbons that are connected to each other by single bonds can each bind to two hydrogens and the carbon on the end can bind to three. We say these fatty acids are saturated because they bind to the maximum possible number of hydrogens (i.e. they are saturated with hydrogens) and those with a double bond are unsaturated. I know it is kind of a weird terminology, just go with it.

Based on everything we have discussed so far, you should be able to predict the key properties of a lipid bilayer (and ultimately the cell membrane). First of all, it forms a barrier between the inside and outside of the cell. Neither ions or polar molecules can cross since to do so they would have to pass though the hydrophobic tails. Hydrophobic molecules not only hate water, they hate anything with charge. They hate ions worst of all since they contain highly localized charge.

Another important property of a lipid bilayer is its fluidity. This refers to the ability of individual phospholipid molecules to slip past one another. Remember, the thing keeping the bilayer together is the repulsion of the fatty acid tails to water. This is sometimes called hydrophobic attraction or even a hydrophobic force, but technically it is all repulsion, there are no real attractive forces between the molecules. It is kind of like a group of people that form because of their common antipathy to other people. They stick together, not because they like each other, but because they hate people that are different from them and by sequestering with similar haters, they avoid interacting with the people they hate. Getting back to membranes, the fatty acids can move around as long as they stay arranged in the bilayer. They just can’t easily move out of the bilayer or even flip from one layer to the other. This latter move does happen, but very rarely. So, although lipids are stuck in the bilayer, they can move within two dimensions; that is, the plane of the membrane. They can also spin around their long axis.

Think of a dance floor where people can move around and do spins, but just need to stay upright (no heads on the floor). The amount of lateral movement of the dancers (phospholipids) relative to each other is referred to as fluidity. For reasons that are not entirely clear, the fluidity of a membrane is very important to its function. We know this because cells go to great lengths to maintain constant fluidity and changes to fluidity can lead to cell death.

One factor that influences fluidity is temperature. Cooler membranes are less fluid, warmer membranes are more fluid. Another factor is the degree of saturation of the fatty acids found in the phospholipids. Because the double bond in unsaturated fatty acids create a kink, the unsaturated fatty acids cannot pack as closely together and therefore can move around easier. Thus, the more unsaturated fatty acids there are in a membrane, the more fluid it is. Going back to the dance floor analogy, saturated fatty acids can just slow dance whereas unsaturated fatty acids can kick up their heels and do some real dancing — moving and twirling around the dance floor.

Some cells have the ability to change the degree of saturation of the fatty acids in their membranes. They appear to use this to maintain constant fluidity despite changes in temperature. If the temperature drops, which would decrease membrane fluidity, the cell increases the proportion of unsaturated fatty acids to compensate. Another means cells have to alter the fluidity of their membrane is by altering the amount of cholesterol. Because cholesterol molecules are shorter than phospholipids, they interfere with the tight packing of saturated phospholipids but actually fill in between phospholipids with unsaturated fatty acids. Thus, cholesterol can have different effects on a membrane depending on its degree of saturation. Membranes with lots of tightly packed saturated fatty acids are made more fluid by the introduction of cholesterol. On the other hand, membranes that are already highly fluid because they have lots of unsaturated fatty acids are stabilized by the addition of cholesterol.

This latter feature explains why a lack of cholesterol can be bad for you. We usually think of cholesterol as bad and freak out a little if our blood test indicates we have high cholesterol. This is because high cholesterol can clog blood vessels, leading to high blood pressure and lack of adequate blood flow to parts of the body. If this is in the heart, it can cause a myocardial infarction, more commonly known as a heart attack. In contrast to the known dangers of too much cholesterol, too little can also be a problem since it leads to unstable cell membranes which lose their integrity and lead to cell death.

Membrane Proteins

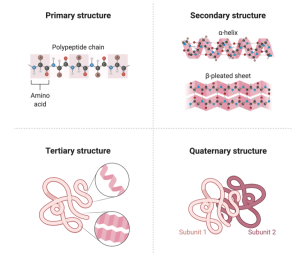

We now come to the second component of the cell membrane, proteins. As I mentioned in the previous chapter, one of the biggest surprises of the past 70 years is that the molecules responsible for the function of cells (and by extension, life itself) are long chains of molecules. Let me say that again, the vast diversity of biological functions are determined by a one-dimensional string of monomers. That is, life is defined in one dimension. (Have I said that enough times?) Proteins are polymers formed from 20 different amino acids. As we already discussed, this linear sequence of amino acids is determined by a linear sequence of the nucleotides in DNA and RNA. I won’t list all 20, but simply mention that there are three main types of amino acids, ones that are non-polar (i.e. hydrophobic), ones that are polar (i.e. hydrophilic), and ones that are ions (i.e. super hydrophilic).

The functions proteins perform are defined by this linear sequence of amino acids. The proteins in your muscle cells that allow you to move are made up of the same amino acids as the proteins in your eye that let you see. The differences are just in the sequence of amino acids that form the polymer. How can that be? How do long polymers of amino acids create such different functions? The answer lies in their secondary, tertiary, and even quaternary structure. Their primary structure refers to the linear sequence of amino acids linked together in a polymer. The higher-level structures (secondary, tertiary, and quaternary) comes about as amino acids interact with other amino acids that are not their immediate partner. For example, two amino acids, one that is positively charged and another that is negatively charged will be attracted to each other. Since the polymer of amino acids is flexible, the chain can fold back on itself allowing distant amino acids to interact. A fact that I still find almost unbelievable is that the specific sequence of amino acids dictates the final shape the protein will take. That is, the protein will bend and fold to create a stable structure and this structure is what determines its function. To be fair, there are a few more factors that influence the final shape of a protein, including its chemical environment, which we will consider next, but the primary determinant of its final shape is encoded in its one-dimensional primary structure.

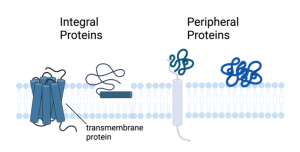

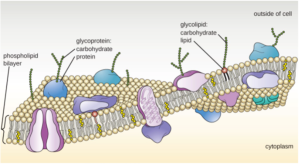

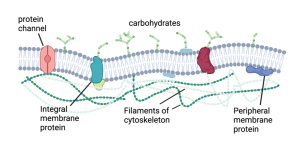

Many proteins reside and function in the cytoplasm, the watery liquid that fills up the cell and in which the organelles (mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, nucleus) are suspended. These are called soluble proteins because they are dispersed throughout the cytoplasm, even though they are not technically dissolved by the cytoplasm. The other category of proteins are called membrane proteins because they are associated with the membrane. Of the membrane proteins there are two major types; integral and peripheral membrane proteins (see below).

Integral membrane proteins.

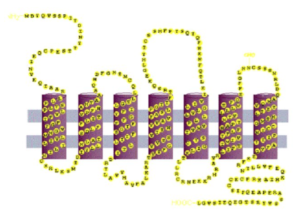

Integral membrane proteins, also called intrinsic membrane proteins, are embedded in the lipid bilayer. They can “float” in the fluid bilayer but, just like phospholipids, they are constrained to the two dimensions of the membrane. They are pretty much stuck in the plane of the bilayer. They can’t jump from one side to the other or do summersaults. However, if they are not fixed in place by interactions with other proteins, they can rotate on their axis running perpendicular to the bilayer (just like phospholipids) and they can diffuse laterally.

As integral membrane proteins are formed, adding one amino acid at a time, the growing string passes back and forth across the lipid bilayer like thread forming a stitch in a garment. For example, the string of amino acids might begin on the inside of the cell and then move across the lipid bilayer to the outside of the cell. Once outside the cell, the string may then turn and pass back to the inside of the cell. Depending on the protein, there may be either one or multiples of these membrane spanning regions. However, regardless of the number, each membrane spanning region usually takes on a specific structure called an alpha (α) helix. An α helix, which is an example of secondary protein structure, looks like a spiral staircase with the string of amino acids spiraling through the membrane as the chain passes from one side of the membrane to the other. (The other secondary structure proteins may take on is called β-pleated sheet, but we will not consider that structure here.)

Why do integral membranes usually take this form when passing through the membrane? Because when the chain is arranged this way, the atoms that form the peptide bonds that connect the amino acids to each other can interact with atoms in peptide bonds further up the chain (approximately 4 amino acids up the chain since this amino acid will be directly over the amino acid directly below it on the spiral staircase). Why is this interaction between the peptide bonds necessary? Because these covalent bonds are polar and polar atoms are not stable within the hydrophobic interior of the membrane unless they can interact with other polar atoms. The α helix allows this to happen and so is one of the preferred ways the amino acids arrange themselves.

So, the α helix secondary structure explains how the atoms that make up the peptide bonds avoid interacting with the hydrophobic tails of the phospholipids, but what about the rest of the amino acids. As I mentioned before, some amino acids are charged or polar. How do they situate in the membrane? They don’t. The membrane spanning regions of integral membrane proteins are composed of hydrophobic amino acids. In fact, this is so common that if proteins contain a stretch of ~20 hydrophobic amino acids, this almost guarantees that this is a membrane spanning region.

Why 20 amino acids? Because such a stretch of amino acids arranged into an α helix is exactly the thickness of a lipid bilayer, 10 nm. In addition to having variable numbers of membrane spanning regions, integral membrane proteins also contain portions that extend into the inside or outside of the membrane. These regions can take on more complex shapes which determine the function of these proteins.

Peripheral membrane proteins.

The other category of membrane proteins are the peripheral membrane proteins, also called extrinsic membrane proteins. These are not imbedded, or integrated, into the membrane like the integral membrane proteins, but instead reside adjacent to the membrane on either side (outside or inside). They form non-covalent interactions with either membrane lipids or integral membrane proteins. In other words, they are more loosely connected to the membrane, being held in place by ionic attraction or hydrogen bonding.

Glycoproteins and glycolipids.

For completeness, I should mention one more class of molecules associated with the membrane. These are the lipids and proteins that have sugars attached to them. They may be a single sugar molecule (e.g. glucose), but more often they are polymers of sugars. Unlike nucleic acids and proteins, sugar polymers can either be single-file chains of monomers or they can branch like a tree or bush. Sugar polymers are found either attached to a membrane lipid, called glycolipids, or to a protein, called glycoproteins. The attachment of these sugar polymers confer specific functions to the lipids or proteins. Most are found on the external side of the membrane and function to interact with other cells or large molecules. The specific sugars and their branching patterns can act as identifiers, allowing cells to recognize each other. For example, the different blood types (A, B, AB, and O) are determined by differences in the types of glycoproteins on the surface of red blood cells. If you receive a transfusion of blood that contains red blood cells that do not match your blood type, your immune cells will not recognize them and mount a vicious attack on these alien intruders.

What do membrane proteins do?

Now that you have a basic understanding of what membrane proteins look like, we can ask, “what do they do?” The answer is, “A lot.” The proteins found in a cell carry out most of its tasks. They differentiate one cell from another. For example, muscle cells and skin cells primarily differ in the specific collection of proteins they express. Similarly, the proteins found in the membrane primarily determine the various functions of the membrane.

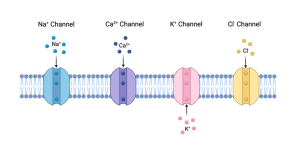

Ion Channels.

For our purposes, the most relevant category of membrane proteins includes Ion channels. Ion channels, as the name suggests, provide passageways for ions to cross the membrane. Since ions are repelled from the interior of the membrane by the hydrophobic phospholipid tails, ion channels provide the only pathway across the membrane for ions, and here is the really cool thing. Because proteins can take on specific shapes (i.e. secondary, tertiary or quaternary structure), ion channels can be highly specific, allowing only certain ions to pass. For example, there are ion channels that only allow sodium ions to pass. Sodium ions, symbolized as Na+, are called monovalent cations because they possess a single positive charge. For short, these are called sodium channels. In a similar way, there are potassium (K+) channels, Chloride (Cl–) channels and Calcium (Ca2+) channels. We will discuss the importance of each of these later.

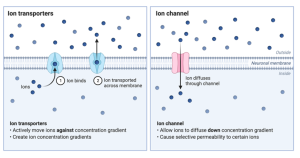

Membrane transporters.

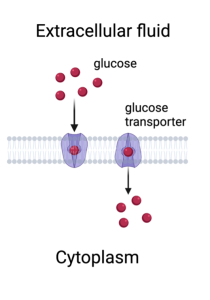

Other than ion channels, the next most important membrane proteins are called transporters. As their name suggests, they transport molecules across the membrane. Isn’t this what ion channels do? As a matter of fact, yes. Ion channels can be thought of as a special subclass of transporters. They are special because they only transport ions and they do it super-fast. A typical ion channel moves ions about a thousand times faster than a regular transporter moves its transportee. The way they do that is fascinating but beyond our purposes here.

Getting back to membrane transporters, some move ions (although much slower than channels do), but many move other polar molecules, such as sugars and amino acids. Just like ions, these molecules are repelled by the interior of the membrane because they have one or more polar covalent bonds, such as an O-H or N-H. One example of this is the glucose transporter. For the delicious cake you just ate to do you any good (or bad), the sugar molecules need to be taken up by cells: muscle cells, nerve cells, fat cells etc. People who have Type I diabetes do not have enough glucose transporters because one of the functions of Insulin, which they do not make in sufficient amounts, is to increase the number of glucose transporters in the membranes of their cells. Thus, even though they may be taking in plenty of sugar and, in fact, have extremely high levels of glucose in their blood, their cells cannot use it and thus starve.

Membrane pumps.

Another type of transporter that is critical for cells to function are the pumps. Just like a water pump which moves water uphill (e.g. out of a well or your flooded basement), these membrane transporters move molecules uphill, metaphorically speaking. For example, they move molecules across the membrane from the side with a lower concentration to the side with a higher concentration. Just like water will naturally flow downhill, if a transporter is present in the membrane, the molecule it transports will naturally flow from the side of the membrane with the higher concentration to the side with the lower concentration. Pumps can reverse this direction. They move molecules uphill. For example, some cells do not just rely on a glucose transporter to take up glucose, but utilize a glucose pump. They can use this to move glucose into the cell even if there already is more inside than outside.

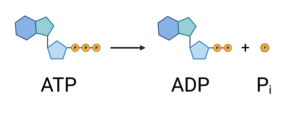

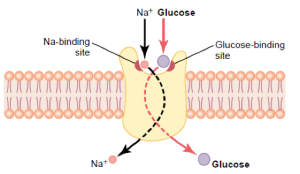

Water pumps have to be plugged in to a source of electricity. Where do membrane pumps get their energy? There are two different ways. They either use the energy in ATP or they use the energy present in an existing concentration gradient across the membrane. In the first case, the pump can break off one of the phosphates in ATP (adenosine triphosphate), forming ADP (adenosine diphosphate) and free phosphate. This releases energy which the protein uses to actively pump the molecule uphill (e.g. from low to high concentration). These transporters, which are also called ATPases because they cut ATP, perform primary active transport. The other type of active transporters are called secondary active transporters because rather than directly using the energy in ATP, they use an existing gradient. For example, the glucose pump mentioned earlier uses the energy that exists in the Na+ gradient across the membrane. Na+ has a higher concentration on the outside of cells relative to the inside. (The cell uses a primary active transporter to maintain this gradient.) By moving Na+ into the cell along with the glucose, the transporter is able to pump the glucose uphill (into the cell). That is all I will say about transporters for now. We will come back to them later since they play a central role in neuron function.

Neurotransmitter Receptors.

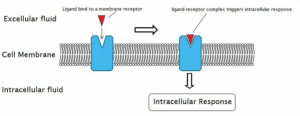

The third example of a type of membrane protein are receptors. These proteins possess a region, usually on the outside of the cell, that recognizes a signaling molecule. Signaling molecules are used by cells to communicate with other cells that they are not directly touching. In the latter case, a glycoprotein might do the job. When these signaling molecules are released at chemical synapses, we call them neurotransmitters. When they are released into the bloodstream where they can travel to distant target cells, they are called hormones. In both cases, the signaling molecule binds to a receptor on the target cell which is specific for the signaling molecule. The binding of the signal leads to a change in the function of the receptor which then alters the function of the cell. We will discuss these events in great detail when we look at synapses.

Other Examples of Membrane Proteins.

Finally, I will just say that in addition to ion channels, transporters and receptors, membrane proteins can also take on a wide range of other jobs. Some function as enzymes, which catalyze (i.e. speed up) chemical reactions. Others provide structure to the membranes. Since the membrane is fluid (rather than rigid) it cannot hold a shape unless it is held in place by proteins. For example, the dendrites and axon that extend from neurons require proteins to create their specific shape. Without proteins, cells would just be blobs. Proteins provide shape by anchoring the membrane to a cytoskeleton. Just like a regular skeleton that gives shape to our bodies and allows our limbs to move, the cytoskeleton does that for cells. It is composed of a web of proteins that form filaments, long tubular proteins, which create something like a cage that sits just below the membrane. They are like the tent poles that support the canvas that forms the walls of a tent. Just as tents have different shapes because of a different pattern of poles, cells have different shapes because of the pattern of the cytoskeletal proteins. Also, similar to tent poles, the cytoskeletal proteins attach to the membrane by binding to specific integral membrane proteins distributed around the cell.

Unlike tent poles, the cytoskeleton can change its shape depending on what the cells needs to do. Wouldn’t it be exciting to go camping in a tent that changes its shape in the night? Or that moves to a different location? (Sounds like a Stephen King horror novel.). This is what the cytoskeleton does. It not only creates a particular shape for a cell, but it allows the shape to change which in certain specialized cells, like amoeba, allows the cell to move along a surface.

Media Attributions

- H2O

- partial charge

- H-bonds2

- H-bonds1

- water drops

- NaCL

- FattyAcid

- Glycerol

- Triglyceride

- Phospholipid

- liposome

- Sat vs Unsat FAs

- Cholesterol

- proteins

- Alpha helix

- membrane-spanning protein

- Integral vs. peripheral proteins

- Glycoproteins and Glycolipids

- ion channels

- Ion transporters vs. channels

- glucose transporter

- ATP

- Na-Glc transporter

- ligand activated channel

- Cytoskeleton