8 The Nerve Impulse – not as important as you might think

Learning Objectives

Understand the following phenomena or concepts.

- Passive signals

- Action potentials

- The voltage-clamp

- The ionic basis of the action potential

- The propagation of the action potential

- Factors that influence the speed of conduction: axon diameter and myelin.

We turn now to the Language of Neurons. How do neurons communicate – with themselves and with the world? Everything we have discussed in previous chapters is a precursor to this question. You will not be surprised to learn that the foundation of this language is electrical. That is, electrical events defined by voltage, current, and resistance (conductance) underly how the nervous systems works. But, before going on, we should pause to consider how radical this idea was to people when first proposed.

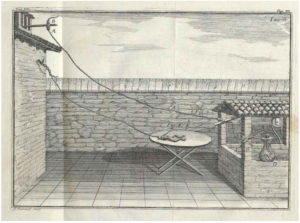

The Italian scientist Luigi Galvani is credited as being the first to demonstrate “animal electricity” near the end of the 18th century. The experiment is depicted in a drawing from his publication in 1791. The illustration shows a dead frog connected to a lightning rod. Much to even Luigi’s surprise, when lightning struck the rod, the frog’s legs twitched. In subsequent experiments performed by Allesandra Volta and others, the lightning was replaced by other sources of electricity.

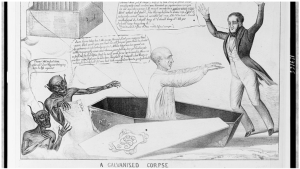

The public was mesmerized by this, with demonstrations of “animal electricity” performed throughout Italy and the rest of the world. In one particularly memorable demonstration, Luigi’s nephew Aldini publicly electrified a recently executed criminal. The headlines read, “scientist reanimates human corpse.”

The public’s macabre fascination with this phenomenon was no more evident than in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which depicts a scientist who took this idea a bit too far.

Passive Electrical Signaling

Before I describe the nerve impulse, which is the title of this chapter, I first need to point out that although nerve impulses are important, even essential, they account for a minority of the electrical signals that animate the nervous system. Most of the signaling that takes place in the brain is passive. It does not involve the events we will consider in detail shortly, which create nerve impulses. Despite their importance, equal to if not greater than the nerve impulse, passive or local potentials are not discussed as much, especially outside the neuroscientific community. In fact, I would bet that this type of signaling is new to you. Why?

Probably because the nerve impulse was characterized first and it is more dramatic. Since it involves the transmission of signals over great distances, both in the brain and in the periphery, it was easier to observe than the passive signals. Remember the motor nerve that travels from your spinal cord to big toe? Such neurons with long axons were the stars of Galvani’s demonstrations. They are relatively easy to stimulate and create a big response. But, the electrical signaling that underlies most of the activity of the brain and is responsible for the complicated processing of neural circuits, is passive. So, what do we mean by passive signaling?

In the simplest of terms, passive signaling is what happens when the voltage across a membrane is briefly changed at one spot in the cell. For example, imagine that a synapse onto one of the tiny spines that project from dendrites (see Chapter 3) is activated. As we will discuss in the next chapter, activation of an excitatory synapse causes ion channels in the postsynaptic membrane (the spine) to open, briefly letting in positive ions. Recall from the previous chapter that the voltage difference across the membrane in a resting cell is negative (we calculated it in chapter 6 to be -88.3 mV in a typical mammalian cell at 37 °C). That is, the voltage is 88.3 mV lower inside compared to outside. The brief influx of positive charge will cause a decrease in the voltage, what is referred to as a depolarization. Initially, this only happens at the place where the depolarization was initiated (e.g. the spine). However, since the rest of the cell, or at least the part of the dendrite close to the activated spine, is still polarized (-88.3 mV), the local disturbance of the voltage at the spine will cause the ions both inside and outside the cell to redistribute. This movement of charge will cause the depolarization to move down the dendrite like the ripples in a pond caused by a pebble. Just like the ripples, the size of the depolarization will gradually decrease as it moves away from its origin.

Although these passive signals do not travel far, compared to nerve impulses, their importance cannot be overstated. They underlie the complex calculations performed by neurons in the brain that are responsible for the higher-level processing that occurs there. Indeed, my ability to come up with these words and your ability to read them involves millions of these passive signals. We will say more about these later, but now we move on to the nerve impulse.

The Nerve Impulse – how it stole the show

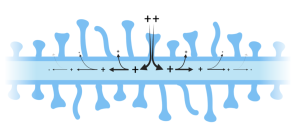

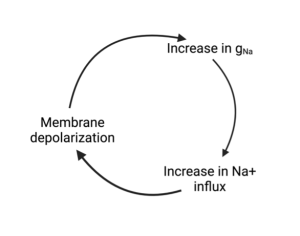

As important as passive signaling is, it has one major shortcoming. It only works over short distances. As animals grew larger than their single cell ancestors, they required a method for reliably sending signals over long distances. Eventually, this long-distance signaling was not only needed to communicate throughout the animal’s body, but was needed to coordinate functions in the growing brain. Enter the nerve impulse. A nerve impulse, also known as an action potential, begins just like a passive potential. There is a brief and local depolarization of a small patch of membrane. The difference, in the case of an action potential, is that the membrane contains voltage-gated ion channels. The most important of these is the voltage-gated Na+ channel. As we discussed in Chapter 3, voltage-gated ion channels are opened by a depolarization of the membrane they reside in. The opening of Na+ channels leads to a rapid influx of Na+ ions, which further depolarizes the membrane. Just like the passive potentials, these depolarizations spread down the cell, for example, an axon. As long as the axon contains voltage-gated Na+ channels along its length, the depolarization (or potential) will keep moving all the way to the end.

The Ion channels responsible for the Action potential

Although scientists suspected that ion channels could behave like this, it took the extraordinary contributions of two groups of individuals to figure out how they worked. The first group were the scientists, Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley (notice, I don’t refer to them as neuroscientists, because the word had not yet been invented). The second group were the squid, who served as the experimental organism Alan and Andrew used to study the action potential. Why squid?

Because squid had evolved an extremely large axon, not extremely long, but extremely thick. Its diameter is up to 1.5 mm, which may sound tiny until you realize that it is the projection of a single cell, making it over 100 times larger than a typical nerve axon. We will learn why these are so large later, but for now, we will just see why their size mattered to Alan and Andrew. The year was 1952 and devices for measuring electricity had not yet been miniaturized. So, Alan and Andrew turned to an organism with an axon that was large enough to record the voltage across its membrane using existing technology. After cutting the axon on one end, they carefully inserted a platinum wire down the middle of the axon. They then stretched another wire along the outside of the axon and connected the two wires to a device that would measure the voltage difference.

You will be making the same type of measurement in lab; however, you will be using microelectrodes that can be employed to measure this voltage in cells much smaller than squid axons. What Alan and Andrew observed is that if they depolarized the squid axon just enough, the axon would “come alive” and the voltage would rapidly change, even switching polarity (i.e. the inside becoming positive), before returning to the original resting voltage (i.e. inside negative).

Using this approach, Alan and Andrew performed many experiments studying this phenomenon and described several important features of action potentials.

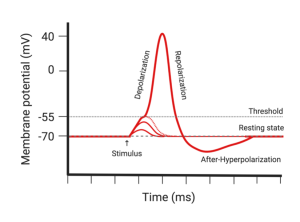

- First, they noticed that the instigating depolarization (i.e. the stimulus) had to exceed a threshold voltage. Depolarizations that fell below the threshold simply dissipated to nothing, just like a passive signal. However, if the depolarization was greater than threshold, the voltage took off, rapidly depolarizing and even reversing the voltage across the membrane.

- The second thing they noticed is that even when the stimulus depolarized the membrane well beyond the threshold level, the peak of the action potential was the same value as when the stimulus raised the voltage just barely above threshold. That is, the action potential is “all or none.” It either happens or it doesn’t. There is no in between.

- Third, they found that the voltage did not remain at its peak for long, but returned back to its original value, called the repolarization phase.

Diagram showing the voltage a membrane during an action potential. The phases of the action potential are labelled. - Their fourth observation was that the axon briefly overcorrected its voltage at the end of an action potential. That is, it repolarized even further than it was prior to the action potential. This is referred to as the after-hyperpolarization.

- Finally, they made the remarkable discovery that the threshold was elevated immediately after an action potential. In other words, if they tried to stimulate the axon a second time within a few hundred milliseconds, they had to deliver a larger stimulus to initiate an action potential. This increased threshold was greatest immediately following the action potential and gradually returned to normal the longer they waited. In fact, if they tried to stimulate too soon after the first action potential, they couldn’t get the axon to fire no matter how large a stimulus they applied. This period of time immediately after an action potential is referred to as the absolute refractory period because it is absolutely impossible to start an action potential. The time after the absolute refractory period where it is possible to start an action potential but requires a larger stimulus is called the relative refractory period.

Alan and Andrew had no idea that this last property, the refractoriness of the action potential, forms the basis of our ability to perceive the strength of sensory stimuli. For example, our ability to distinguish a gentle touch from a strong punch, or a dim light from a bright light depends on this fundamental property of action potentials. More about this later, but first, we will follow Alan and Andrew as they devised a method to figure out how voltage-gated ion channels led to the features they had observed in the squid axon.

The Voltage-Clamp

Alan and Andrew realized that the phenomena responsible for the action potential were complicated. There were no easy explanations for the behavior they had observed in the squid axons. That didn’t stop them from trying however. They began by thinking carefully about the problem. Their first major insight was to realize that, at least in theory, one should be able to consider the movement of ions across the membrane in terms of current made up of individual currents carried by the different ions. For example, the total charge moving across the membrane through ion channels was being carried by Na+, K+, Cl–, Ca2+ and maybe others. (To simplify things, they ignored the roles of Cl– and Ca2+ and assumed all of the charge was carried by Na+ and K+, which ended up fortuitously to be uniquely true for squid axons.)

Since ion channels are selective, it makes sense to separately consider the contribution of each ion to the total current. They designated these subcurrents as iNa and iK, where Itotal = iNa + iK. Notice, they used a lower case i to refer to these components of the total current passing across the membrane, Itotal. In a similar manner, it makes sense to consider the total resistance of the membrane or, more conveniently, the total conductance of the membrane being made up of Na+ and K+ conductances. That is Gtotal = gNa + gK. What made this insight so useful is that it allowed them to describe the movement of Na+ and K+ not just in terms of the voltage across the membrane but also the differences in their concentrations across the membrane. Since the latter influence had been shown by Walter Nernst to be equivalent (and opposite) to the Nernst potential, Alan and Andrew combined the Nernst potential with ohms law to write equations describing the Na+ and K+ currents:

![]()

What these mini ohm’s law equations state is that the current carried by each ion is proportional to its conductance, i.e. how many open ion channels are present, and the difference between the voltage across the membrane and the ion’s Nernst potential. To help make sense of this, consider what these equations tell us about the movement of an ion across the membrane if the voltage is equal to the ion’s Nernst potential. For example, how many Na+ ions will move if Vm = ENa?

The equation says that if Vm = ENa, then, Vm – ENa = 0 and iNa = 0. Notice, gNa doesn’t matter; that is, it doesn’t matter how many Na+ channels are open; no Na+ will move across the membrane. Why? Because, the voltage across the membrane is pushing Na+ out of the cell with the same force that the difference in Na+ concentration is pushing Na+ in. The two forces balance each other; Na+ is at equilibrium. If Vm is not equal to ENa, then the net force on Na+ is the difference between Vm and ENa. Either Vm is larger, in which case more Na+ will be pushed out than in or Vm is smaller and the opposite will be true. Obviously, the same reasoning can be applied to K+ (and Cl– and Ca2+ but Alan and Andrew didn’t consider these).

With these equations reasoned out, Alan and Andrew could see why the events taking place during an action potential were so difficult to analyze. Each equation contained two variables and one of the variables depends on the other. Vm is one variable and, normally a change in Vm is what initiates an action potential. So far, the problem doesn’t seem too bad, until you realize that a change in Vm changes gNa. That is, the depolarization of the membrane influences the voltage-gated channels and the opening or closing of channels changes gNa (and gK). So, now you may be able to see the problem. INa is influenced by two changing variables, Vm and gNa, and the change in Vm is also changing gNa. But it gets worse. The change in gNa, which is caused by the change in Vm, changes iNa, and the change in iNa changes Vm, which changes gNa even more and on and on it goes.

Are you confused yet? This is called a positive feedback loop and positive feedback loops are hard to analyze. An explosion is an example of positive feedback. Imagine (but don’t really do this) tossing a match in a barrel of gun powder or some other explosive. Of course, this will create a big bang, but slow down the action. First the heat of the match ignites the powder it falls on. The ignition of this gun powder creates heat, which ignites more gun powder. The ignition of this gun powder ignites the rest and so on and so forth until all the gun powder has ignited. This all happens very fast which is why in real time you just hear a loud boom (and might feel it if you are close enough).

A similar positive feedback loop occurs with Na+ during the rapid depolarizing phase of an action potential. A small depolarization, like the match, opens Na+ channels. The influx of Na+ causes more depolarization which causes more Na+ channels to open which causes the influx of more Na+ etc. This sequence of events has been called the Hodgkin cycle (which I admit sounds more like a prop at the circus than a scientific concept).

So, what did Andrew and Alan do once they had this concept of individual ion currents? They used a device developed by KC Cole and John Moore called a voltage clamp. What is a voltage clamp? Well, obviously it clamps voltage, but how does it work? I will answer this by comparing it to a room in which the temperature is controlled (i.e. clamped) by a thermostat and a heater or an air-conditioner or both, just like the room you are currently in (assuming you are not outside). Most likely, the temperature around you is a pleasing 72 °F and it doesn’t change much during the day (unless your thermostat is broken or you have a fancy programmable thermostat that adjusts the temperature depending on the time of day). How does it maintain a constant temperature? The thermostat contains a thermometer that constantly measures the temperature in the room. If the temperature is 72 °F (or whatever you set the thermostat to), nothing will happen; however, if the temperature drops below 72 °F, the thermostat will turn on the heater and the heater will raise the temperature until it reaches 72 °F and then it will shut off. In contrast, the air conditioner will kick on if the temperature rises above 72 °F. I probably have not told you anything you did not already know about thermostats, but have you ever thought about the fact that the amount of heat your heater puts out (measured in BTUs or whatever) is exactly equal and opposite to the heat that is leaking out the windows, walls and doors of your room. If they were not equal and opposite, the temperature would change. Thus, if you ever need to know how much heat you are losing because of poor insulation or faulty windows, just measure the amount of heat being pumped into the room (or, look at your energy bill!).

Now that you are familiar with thermostatically controlled rooms, understanding the voltage clamp will be easy. Remember the wire Alan and Andrew slid down the squid axon to measure the voltage across the membrane. To perform a voltage clamp experiment, they just had to insert one more wire that they used to inject current into the axon. (Since the current could be either positive or negative, they could use this electrode to either make the voltage inside more or less negative.) They connected the voltage recording electrode to a device that compared this voltage with a Command voltage. That is, the voltage they wanted across the squid axon. This is just like setting the temperature on the thermostat. The only difference is the command voltage could be switched rapidly, which allowed them to see what happened to the channels in the membrane when the voltage changed during an action potential.

If the voltage ever differed from the command voltage, current would be injected until the voltages matched. Most importantly, they could record the amount of current that needed to be injected. Since this was equal and opposite to the current passing across the membrane, this allowed them to see what was happening in the membrane of the squid axon. More specifically, this allowed them to measure the current flowing across the membrane, which was composed of iNa and iK. Since the voltage was being clamped, any change in current had to be caused by a change in conductance; that is, changes to gNa and gK.

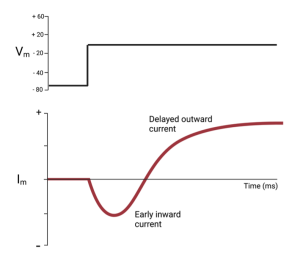

The following trace shows what they measured when they changed the voltage across the squid axon membrane from -70 mV (similar to the resting potential) to 0 mV. Notice, that shortly after the voltage was changed, currents flowed across the membrane, first inward and then outward. Since the voltage was held constant after the step to 0 mV, the changes seen in Im reflected changes to Gm.

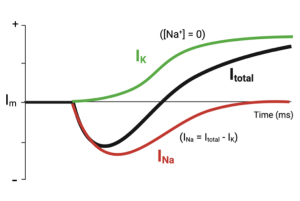

Although the voltage clamp allowed them to break the feedback cycle that complicated their ability to measure the effect of the changing voltage on the ion channels, it didn’t separate the currents carried by Na+ from those carried by K+. To do this, they removed Na+ from the solution on the outside of the axon and repeated the measurement. If there is no Na+, there can be no Na+ current. (To maintain osmotic balance, they did this by replacing the Na+ with a positive ion that did not pass through the channels in the membrane.). When they repeated the experiment in the absence of Na+, they measured the current shown by the green trace in the next figure.

Notice, the inward portion of the current is now missing and only current leaving the cell remains (green trace). They assumed this remaining current was being carried by K+ and told them how the K+ channels responded to the rapid depolarization of the membrane. To recreate the Na+ current they subtracted the K+ current from the total current they had measured originally (red trace). Recall, Itotal = iNa + iK. Thus, iNa = Itotal – iK)

They repeated these sets of experiments at several different voltage steps that occurred during the action potential so they could recreate what was happening at each step. These experiments taught them the following about the voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels responsible for the action potential.

Characteristics of Na+ and K+ channels

| Na+ channels | K+ channels |

| Open rapidly following depolarization | Open less rapidly following depolarization |

| Let Na+ enter the axon when opened | Let K+ leave the axon when opened |

| Inactivate following depolarization, stopping Na+ entry | No inactivation, allowing K+ to continue exiting |

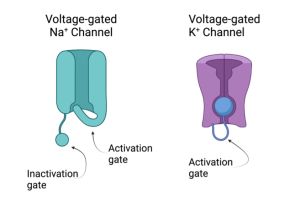

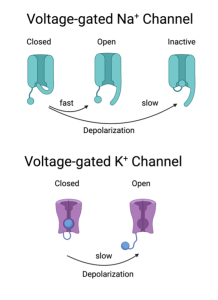

From these properties, they imagined that Na+ and K+ channels had the properties illustrated in the cartoons shown on the left.

A subtle but important feature of the Na+ channel is that it has two gates and they are not the same, although both are influenced by depolarization. One gate is the activation gate which is rapid and allows Na+ to enter the axon. The other gate is called the inactivation gate (it moves independently of the activation gate). Depolarization causes this gate to close, but this closure is slower than the activation gate. Thus, the Na+ channel only conducts Na+ ions for a brief time. In contrast, the K+ channels have only one type of gate. Depolarization activates the K+ channel, but these activation gates are slower than the activation gates on Na+ channels. In fact, they activate the K+ channels at approximately the same time the Na+ channels are inactivating. Unlike the Na+ channels, the K+ channels will remain open until the voltage returns back to its normal (i.e. resting) level.

The Ionic Basis of the Action Potential

With their new understanding of the behavior of voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels, Alan and Andrew were able to reconstruct the ionic basis of the action potential.

- Overview. The depolarizing phase of the action potential is caused by the opening of Na+ channels. This causes the voltage to rapidly depolarize and even overshoot 0 volts, becoming positive inside rather than negative. (Quiz question: What is the maximum voltage the membrane can rise to?). Shortly after reaching the peak, the membrane repolarizes. This repolarization is caused by two factors: (i) the Na+ channels inactivate and (ii) voltage-gated K+ channels open (remember, this adds to the leak K+ channels)

- Threshold. They explained the existence of a threshold as the minimum stimulus needed to activate enough Na+ channels to allow more Na+ to enter the axon than the amount of K+ leaving it. Remember, the leak K+ channels are always open and the efflux of K+ makes the voltage negative. Thus, enough Na+ channels must be activated to allow more positive ions to enter (Na+) than to leave (K+).

- After-Hyperpolarization. The observation that the voltage briefly becomes even more negative after an action potential than it was before can be explained by the fact that additional K+ channels were opened during the action potential and some time is needed before they close again. Thus, there is even more K+ efflux than before the action potential.

- Refractoriness. The refractory periods now made sense as well. Since the Na+ channels become inactivated by depolarization and the inactivation gates do not reset immediately after the voltage is re-polarized, the Na+ channels will not conduct Na+ no matter how strong the stimulus and how many activation gates are opened. To conduct Na+ through the channel, both gates must be open. If either gate is closed, Na+ will not be able to move through. Thus, the axon is absolutely refractory while the Na+ channels are inactivated. During the relative refractory period, the inactivation gates on the Na+ channels are resetting one by one and the activation gates on the K+ channels are closing one by one. During this time, an action potential can still be initiated but will require a greater stimulus.

Tetrodotoxin and Fugu

At around the same time that Hodgkin and Huxley were doing their experiments on squid axons, John Moore and colleagues (Duke University) were characterizing the effects of a toxin isolated from the Japanese puffer fish. The toxin, named tetrodotoxin (TTX), is extremely dangerous and can be fatal to humans at very low doses. Moore and colleagues showed that TTX specifically binds to voltage-gated Na+ channels and prevents their activation. Because of the high-degree of specificity of TTX and its tight binding to the V-gated Na+ channel, its discovery greatly facilitated our understanding of the role of these channels throughout the nervous system.

Despite containing a potentially fatal toxin, puffer fish are regarded as a delicacy in Japan and are served as fugu in high-end restaurants. With appropriate care, the organs of the puffer fish that concentrate most of the TTX can be removed, making the fugu safe for consumption. The Japanese government requires that chefs receive the proper training before being allowed to serve fugu to customers. Despite these precautions, there are still a few deaths from fugu poisoning each year (these are usually the result of people preparing the fugu themselves).

How does the Action Potential Propagate (i.e. move)

The squid axon and the voltage clamp technique were great for working out the details of the action potential (and it earned Alan and Andrew a trip to Sweden to receive the Nobel Prize); however, there was one small problem. The action potential didn’t go anywhere. Since the platinum wires ran down the entire length of the axon, they were measuring the voltage across the membrane as it changed simultaneously along the axon. Clearly, that is not what happens in nature. In fact, the purpose of the action potential is to transmit a signal down the length of an axon. So how does this happen?

In a non-voltage-clamped axon, the membrane is depolarized at just one spot along the axon. Typically, this happens right where the axon starts; that is, where it begins projecting out from the cell body, a region called the axon hillock. Thus, the events we just went through only happen at the beginning segment of the axon, but just as we saw with passive signaling, the depolarization spreads away from the initial segment down the axon. This spreading depolarization then activates Na+ (and K+) channels further down the axon and the process repeats. This continues until the action potential reaches the end of the axon and there is no more membrane to depolarize. This process has been compared to falling dominoes. The first domino tips the second, which tips the third …. all the way down the line until you run out of dominoes.

Now, if you are paying real close attention and following the logic so far, you may have thought of a problem. Why does the action potential move only one direction down the axon? Why doesn’t it turn around halfway down? The passive spread of current does not have a preferred direction, it will just flow from higher to lower voltage. So, it must not only flow down the axon but also move back up the axon toward the previous location where the voltage has now returned to its negative value. Why doesn’t this reverse flow re-trigger an action potential in the location it just left? Hint: what is different about the membrane immediately after an action potential?

If you said (or thought), it is refractory, you are correct! One of the purposes of the refractory period, specifically the absolute refractory period, is that it makes sure the action potential only goes one way and doesn’t repeatedly back track. (This goes awry during a heart attack and results in ventricular fibrillation. Ask me to tell you about this sometime if you are interested.)

What determines the speed of action potential propagation?

Animals that conduct their action potentials faster will have an advantage, especially if the axons are being used to conduct an action potential to large muscles that become employed during an escape response. Avoiding the jaws of a predator can literally be a matter of life or death. So, what determines this speed? First, let’s look at what does not play a major influence on speed. (i) It is not due to how fast the ion channel gates move and (ii), it is also not due to the speed the current moves down the axon. Both of these are relatively constant. What is it then?

The speed of propagation is mostly determined by the distance signals spread passively down the axon. The farther they spread, the faster the action potential. To help explain why this is, I offer the following analogy. Imagine the following strange game. It is played with a football on a football field, but not the way football is normally played. In this game, the object is to move the football from one goal line to the other faster than your opponent. Each team can use 11 players but they are not required to use all 11. So far, it doesn’t sound that much different from the actual game, but here is where the rules are different. After taking a position on the field, the players cannot move. The only way to move the ball is by throwing it.

The strategy of two competing teams is diagrammed below.

On team 1, all 11 players were used and they positioned themselves along the football field every 10 yards. Team 2 only used two players. They picked two players who could throw the ball 50 yards. (I think one of them was named Aaron “Something or other” and the other player was named Tom “something or other”.) Which team won? Obviously, unless either Aaron or Tom suddenly pulled one of their arm muscles so they couldn’t throw the ball 50 yards, team 2 won. Why? Did they throw the ball faster? Maybe a little bit, but not enough to explain the trouncing. The difference is they only had to throw the ball twice and catch it once compared to team 1 that had to throw it 11 times and catch it 10 times. Catching and throwing a ball takes time and this is what slowed down team 1.

Back to axons. Just as in the football game, the axon that can pass the voltage farther will be faster because the time-consuming step is the activation of the voltage-gated channels. Notice from Alan and Andrew’s voltage clamp experiments that the Na+ channels do not open instantly; it takes some time to get the gates to open. Since this is where time is being lost, the axon that needs to do this less often along the axon will be faster.

So, what is the axon equivalent of Aaron and Tom? Axons use two different strategies for increasing speed; that is, for throwing the charge farther down the axon. The first and oldest strategy is to increase the diameter of the axon. Just as a leaky garden hose with a larger diameter will let the water flow farther from the faucet, so will a larger axon pass current farther down the axon. Basically, a larger diameter means a larger cross-sectional area which means there is a larger (lower resistance) path for current to flow. Since it can flow farther, the patches of membrane that must successively fire an action potential are farther apart.

An extreme example of this is the squid. The giant axon carries danger signals from the head of the squid to the muscles of its mantle. When these muscles contract, the squid shoots water out one end propelling it the opposite direction (hopefully, away from the predator). At the same time, the squid squirts ink out into the water to camouflage its quick get-away. Evolution has been improving this response by increasing the diameter of the axon and thereby increasing the speed of the response. The squid able to respond quickest lives to see another day (and pass on her large axon genes to her baby squid.)

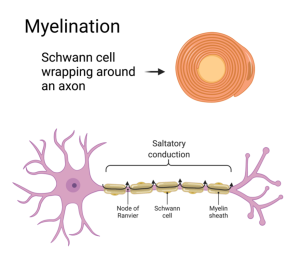

This is one strategy. The other is more recent, on an evolutionary time scale, and involves insulating the axons so less charge escapes out the membrane, allowing the current to spread farther down the axon. This is analogous to wrapping the leaky garden hose with duct tape to reduce the amount of water leaking out. The insulation used by axons is called myelin.

Glial cells, called oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system and Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system, wrap around the axon in a process called myelination. The cell membranes of the glial cells are impermeable to ions and thereby block the diffusion of ions out of the axon. The myelin wrapping is interrupted every few millimeters along the axon where the membrane concentrates its voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels. These un-myelinated openings are called Nodes of Ranvier. The action potential jumps from node to node, a phenomenon called “saltatory conduction” from the latin verb saltare which means to jump or leap.

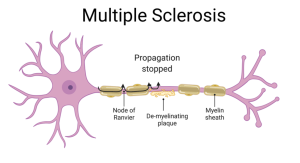

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a disease caused by damage to the myelin sheath. People with MS suffer from sensory and motor deficits because the ability to conduct action potentials down long axons is compromised. Not only are parts of the sheath missing, but the exposed nerve lacks voltage-gated Na+ channels along most of its length since these were only inserted at the original nodes of Ranvier.

Media Attributions

- Galvani_Frog_C5

- Galvani_Electrification_C5

- Depolarization_C5

- Hodgkin_Huxley_C5

- Squid_C5

- SquidAxon_VoltageMeasurement_C5

- MembranePotentialOverTime_C5

- Screenshot 2024-11-13 at 15.04.49

- NaDepolarization_C5

- Squid_VoltageClamp_C5

- Vm_Im_C5

- iNa_iK_C5

- Na_K_Channel_C5

- Na_K_Channel_OpenClose_C5

- Screenshot 2024-12-22 at 12.23.03 PM

- CompetingTeams_C5

- Myelination_C5

- Multuple Sclerosis_C5