11 Presynaptic Details

Learning Objectives

Understand what was learned about synaptic transmission using the frog neuromuscular junction

- Stimulation of the motor axon produces a local depolarization of the muscle at the end-plate (the EPP).

- Without stimulation of the motor axon, spontaneous depolarizations are detected at the end-plate (the mEPPs)

- Neurotransmitter release is quantized. EPPs are made up of multiple mEPPs.

- Quantal neurotransmitter release is stochastic, and can only be described as a probability distribution.

- A quantum of neurotransmitter corresponds to the contents of a single synaptic vesicle.

Much of what we currently know about the events associated with the release of neurotransmitter at chemical synapses was discovered by Bernard Katz and colleagues who studied the frog neuromuscular junction. Just as Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley realized that the giant axon in the squid would be ideal for learning about the action potential, Bernard and friends thought the synapse between a nerve and muscle provided advantages for learning about synaptic transmission. The synapse between a nerve and muscle, called the neuromuscular junction, has the distinction of possessing a very large postsynaptic cell. Unlike the tiny spines on neuronal dendrites, which may be less that 1 µm (i.e. 1 millionth of a meter), muscles are much larger, typically 50 – 100 µm wide by centimeters long. Just as with the squid axon, this large size simplifies the recording of postsynaptic electrical events. They decided to use frogs because they were cheap and easy to work with.

The discovery of the end-plate potential (EPP)

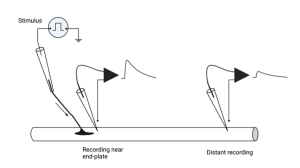

The basic set-up they used is shown above. A muscle and its associated nerve axons are exposed and separated from other tissues so the experimenter can electrically stimulate the nerve axon and record from the muscle cells. The nerve can be readily stimulated by sucking its end into a glass pipette and delivering electrical stimuli to the axon. If the provided stimulus is greater than threshold, the nerve axon will fire an action potential and the action potential will propagate down the axon to the nerve terminal. Meanwhile, the voltage across the muscle membrane is recorded using an intracellular microelectrode. If done carefully, the tip of the electrode can be inserted inside the muscle cell without damaging the muscle. (You will see how to do this in lab by recording membrane voltage in crayfish muscles). The voltage at the tip of this microelectrode is then compared to another electrode placed outside the muscle. The voltage difference between these two electrodes represents the voltage across the membrane. A diagram of this experiment is shown above, along with an example of what the intracellular microelectrode records at two different locations relative to the nerve terminal.

Bernard noticed two important features of these recordings. First, the amplitude of the depolarization in the muscle that followed stimulation of the nerve depended on where along the muscle cell the electrode was inserted. It was largest close to the nerve terminal; an area called the end-plate because early investigators thought the muscle membrane looked a little like a dinner plate where the nerve ended (my guess is that they were just really hungry when they gave it this name). As the electrode was inserted progressively farther away from the end-plate, the size of the depolarization, which they called the end-plate potential or EPP for short, was smaller and eventually disappeared. What does that remind you of? Hopefully, you thought of passive electrical potentials, because that is exactly what this is and, in fact, is what all synaptic potentials are. They are generated at the synapse and passively spread out from there.

The tricky thing about this experiment is that Bernard had to add a small amount of poison to the muscle to clearly observe the EPPs. The poison was d-tubocurarine chloride, or just curare for short. Curare can be extracted from the bark or stems of some South American plants. Native people in Central and South America would coat their arrows or darts with this poison since it would paralyze their prey and increase the success of the hunt. Curare works by binding to the receptors on the muscle and interfering with the binding of the neurotransmitter, which is acetylcholine (ACh) at neuromuscular junctions in vertebrates. By applying curare, they could reduce the amplitude of the EPPs so they were not large enough to trigger an action potential in the muscle. Normally, when we are minding our own business and avoiding poison darts, our EPPs will be strong enough to start an action potential in the muscle. This is because muscle cells contain voltage-gated Na+ and K+ channels, just like squid axons.

While a muscle action potential is desirable if you want to move, since it is required to initiate contraction (the mechanism for that is a subject for another course), it is not desirable if you are trying to measure the EPP that initiates the action potential. First of all, action potentials are large and obscure the full EPP. Second, action potentials cause the muscle to contract, which will rip the fragile microelectrode out of the muscle – experiment over. Bernard’s insight was to realize that if they added a little bit of this poison to the frog muscles, they could reduce the size of EPPs so they were below threshold for triggering a muscle action potential. Yet, if they added just the right amount of curare, not too much and not too little, they could still measure EPPs.

The Discovery of miniature end-plate potentials (mEPPs)

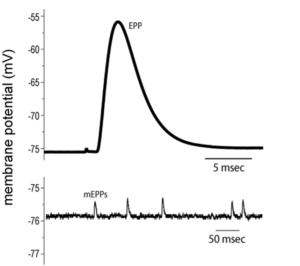

That was Bernard’s first important insight (and yes, this work also earned him a trip to Sweden to receive the Noble prize). The second was to notice that if he inserted a microelectrode near the end-plate and didn’t stimulate the nerve, he recorded tiny random depolarizations of the muscle membrane. He called these miniature end-plate potentials, or mEPPs, because they had the same shape and properties of EPPs. Their amplitude decreased as the electrode was moved away from the end-plate or if curare was added.

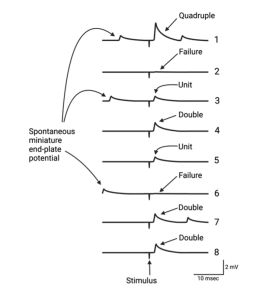

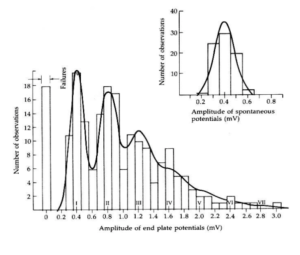

While a mere mortal might have noticed these tiny depolarizations and moved on, Bernard was no mere mortal. He suspected that the mEPPs combined to produce EPPs. To test the idea that EPPs are made up of units the size of the mEPPs, Bernard and colleagues bathed a frog neuromuscular junction in a solution that had significantly reduced Ca2+ concentration. Recall that the influx of Ca2+ into the nerve terminal causes the vesicles to fuse with the membrane and release neurotransmitter. With less Ca2+ outside the cell, fewer Ca2+ ions will diffuse into the nerve terminal when the voltage-gated channels open. Since the buildup of Ca2+ triggers vesicle exocytosis, less neurotransmitter will be released. When Bernard and his colleagues performed this experiment, the result was a surprise (maybe not to them, but at least to me). As shown in the figure above, the amplitude of the EPPs decreased as they lowered Ca2+, as expected, but when they made the Ca2+ concentration low enough they observed fluctuations of successive EPPs. The amplitudes of the EPPs observed following nerve stimulation were multiples of the spontaneous mEPPs they had recorded when the nerve was not stimulated. On average, the EPPs were 1 times, 2 times, 3 times… the size of a mEPP and even some were 0 times. That is, in the latter case there was no EPP after stimulation. They called these “failures”, which is something of a misnomer as you will see shortly. These experiments led Bernard to propose the quantal nature of neurotransmitter release.

The quantal nature of neurotransmitter release.

A quantum refers to a discrete quantity of something. For example, physicists tell us that light is made up of discrete particles, or quanta, called photons. In the same way, Bernard and colleagues proposed that EPPs are made up of quantal units. During spontaneous neurotransmitter release, the nerve terminal releases single quanta, which are observed as mEPPS. During stimulated release, also called evoked release, the nerve terminal releases multiple quanta to produce the EPPs. The really surprising thing was that the number of quanta released following nerve stimulation was stochastic, that is, it had a random probability distribution. The way to think of this is that the influx of Ca2+ into the presynaptic terminal increases the probability that the synaptic vesicle will fuse with the membrane; however, it doesn’t not guarantee that the vesicle will fuse.

Bernard must have been paying attention during math class because these observations reminded him of a binomial distribution. Binomial means “two names.” There are many events that can be classified this way, such as flipping a coin. Such events form a distribution, called a binomial distribution, that can be predicted knowing the probability of each outcome (heads or tails) and the number of objects (e.g. coins) being observed. For example, if you repeatedly flip 3 coins and count the number of heads in each trial, you can predict how many times each combination of heads and tails will occur during 1000 flips (e.g. no heads, one head, two heads etc.). In case you are interested, you will get no heads 125 times, 1 head 375 times, 2 heads 375 times, and 3 heads 125 times (give or take one or two). In other words, although you cannot say how many heads will show up on any given trial, you can predict the distribution of events.

The distribution of EPPs observed in the low Ca2+ experiments could be fit to a binomial distribution. This revealed that neurotransmitter release is a stochastic process. Following each nerve stimulation, a specific number of quanta of neurotransmitter will be released, but just like with the coins, it is not possible to predict exactly how many quanta will be released during each stimulus. (Pause, for deep philosophical reflection. Since synaptic transmission underlies our thinking, does the stochastic nature of neurotransmitter release account for a certain degree of randomness in our thinking and decision making.)

What is the physical basis of a neurotransmitter quantum?

After the quantal basis of neurotransmitter release was observed, neuroscientists began speculating as to the physical basis of a quantum. One rather simple idea was that a quantum was a single molecule of neurotransmitter; however, this was quickly dismissed because it was observed that the addition of ACh to the extracellular solution caused a gradual depolarization of the muscle. No quantal-like events were ever observed, even when the concentration of ACh was reduced to almost nothing.

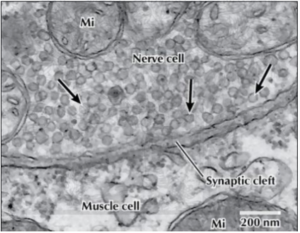

Around the same time that Bernard was doing his experiments, other scientists were turning their electron microscopes toward synapses. Synaptic vesicles were a feature of all synapses and they were only found in the presynaptic terminal. Most scientists guessed that the vesicles seen in these electron micrographs, or more specifically, the neurotransmitter contained in a vesicle, corresponded to a quantum. Although this seemed highly likely, experimental proof of this equivalency would not exist for decades.

The quantal nature of neurotransmitter release is now well established as is the fact that a quantum corresponds to the contents of a synaptic vesicle. This has been generalized to all chemical synapses, not just the neuromuscular junction.

Media Attributions

- Private: RecordingWithElectrode_C6

- Private: mEPPs_C6

- Private: EPPAmplitude_C6

- Private: EPP_SpontaneousPotential_Observations_C6

- Private: SynapticCleft_MicroscopeImage_C6