20 Synaptic Plasticity

Learning Objectives

Understand the different forms of presynaptic modulation

- paired-pulse depression

- paired-pulse facilitation

- tetanic depression and potentiation

- post-tetanic poentiation

- long-term potentiation (LTP)

Synaptic modulation

In the first chapter of this section on neuronal communication, I mentioned that the advantage of chemical synapses – the advantage that outweighs all of its disadvantages relative to electrical synapses – was the ability to change, that is, plasticity. This property allows animals to modify behavior depending on experience and environmental conditions. Without this flexibility, animals would never have been able to spread out and adapt to virtually every environmental condition on the planet. Furthermore, animals would not learn from either their own experience or, especially in the case of humans, from the collective experiences of others. This is why synaptic modulation is such an important subject. Here we consider some of properties of synaptic modulation.

Pre- vs. post-synaptic modulation.

Since a chemical synapse contains both a presynaptic and a postsynaptic component, there are two ways synaptic transmission can be changed. Either the presynaptic cell changes the amount of neurotransmitter it releases when activated or the postsynaptic cell changes its response to the neurotransmitter. Or, both can happen at the same time. Since neurotransmitter is released by the exocytosis of synaptic vesicles, the full content of the vesicle is always released. (Note: exceptions to this have been reported, but do not appear to be common.) Furthermore, synaptic vesicles are always loaded with the same number of neurotransmitter molecules. (Once again, there have been reports of exceptions to this rule as well.) Thus, the only way to change the amount of neurotransmitter released is if more or fewer vesicles exocytose when the nerve is active. This number is referred to as the quantal content. That is, how many quanta (vesicles) are released when the presynaptic nerve is active (e.g. firing an action potential).

The other way to change the strength of a synapse is to alter the response of the postsynaptic cell to neurotransmitter. This can come about in several ways but the most common mechanism involves a change in the receptors in the postsynaptic membrane. Either the number of receptors or the activity of each receptor is changed. In what follows, we will just consider presynaptic mechanisms in detail.

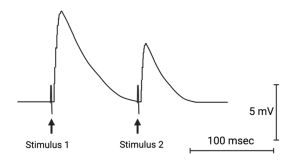

Paired-pulse depression.

The simplest form of plasticity is induced by stimulating the presynaptic nerve twice in close succession. If the delay between the two stimuli (the pairs) is less than 200 milliseconds, the second stimulus will release either more or fewer quanta of neurotransmitter. Whether a synapse facilitates or depresses depends on how much neurotransmitter is released by the first stimulus. Some synapses are weak and others are strong, depending on their role. For example, the neuromuscular junction is a strong synapse. When a pair of pulses are delivered to the nerve, the second stimulus will release less neurotransmitter than the first.

This paired-pulse depression is due to the relative depletion of synaptic vesicles that are ready and available to be released (i.e. they have been loaded with neurotransmitter and moved up to the site on the presynaptic membrane where they will be released). Since a large fraction of these vesicles are released following the first stimulation, there are fewer available to be released following the second stimulation. It takes some time for the nerve terminal to replace the released vesicles with new ones.

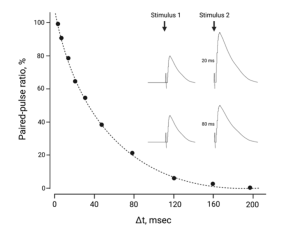

Paired-pulse facilitation.

On the other hand, if the Ca2+ concentration is reduced outside the neuromuscular junction, as Bernard and colleagues did to reveal the quantal nature of neurotransmitter release (Chapter 11), the number of vesicles releasing their contents following the first stimulus is much reduced. Not only does this prevent a depletion of vesicles that could lead to depression, the nerve releases even more vesicles following the second stimulus of the pair. This facilitation is due to residual Ca2+. The Ca2+ that entered the nerve terminal during the first stimulus has a residual effect, which adds to the Ca2+ that enters during the second stimulus.

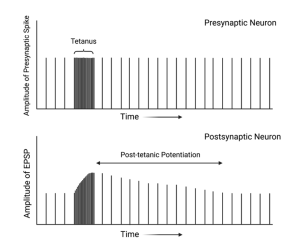

Tetanic potentiation or depression.

This form of plasticity is similar to what happens during paired pulses, except multiple stimuli are applied close together. If the presynaptic nerve is stimulated repetitively at frequencies greater than 10 Hz (i.e. 10 times per second), the nerve will either release progressively more or less neurotransmitter with each successive stimulus. The same principles and mechanisms apply as for paired-pulses (e.g. vesicle depletion, residual Ca2+), but some additional factors may also come into play. For example, the concentration of Na+ inside the nerve terminal can accumulate, leading to subsequent changes to Ca2+. Also, with repetitive stimulation, Ca2+ diffuses deeper into the nerve terminal and may activate a protein kinase, which phosphorylates proteins involved in moving the vesicles up to the membrane. This can result in more vesicles ready for release and a slow increase in the number releasing neurotransmitter per stimulus.

Post-tetanic potentiation.

Some synapses will begin releasing more neurotransmitter after a period of high-frequency stimulus. This increase may not occur until several seconds or minutes after the high-frequency stimulation and may persist for tens of minutes. This type of plasticity is less well understood, but may involve the activation of metabotropic receptors on the presynaptic nerve terminal. These auto receptors play an important role in synaptic modulation through out the nervous system and can be involved in potentiation or depression.

Long-term Potentiation.

Long-term potentiation, or LTP, refers to a type of plasticity that was first identified at synapses in a part of the brain called the hippocampus, which was thought to be crucial for the formations of certain types of memory. The link between the hippocampus and memory was solidified by the tragic case of Henry Molaison (“Patient H.M.”), who underwent surgery to remove both hippocampuses to treat severe epilepsy. This surgery, while successful in controlling his seizures, resulted in a profound inability to form new long-term memories. (see Chapter 49 for a more complete description of Henry Molaison and LTP.)

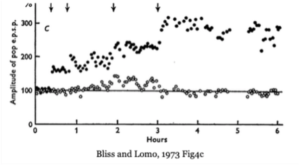

The discovery of LTP in the hippocampus by Timothy Bliss and Terje Lomo was highly significant. They found that LTP could be induced by either repeatedly stimulating a neuron or by simultaneously activating multiple connections onto a single neuron. Crucially, this enhanced synaptic strength persisted for hours or even longer. Given the known role of the hippocampus in memory formation and the long-lasting nature of LTP, neuroscientists quickly recognized its potential as a key mechanism underlying the formation of memories.

The above figure summarizes the classic experiment by Bliss and Lomo showing that brief periods of high-frequency stimulation at a synapse in the hippocampus increased the amplitude of post-synaptic potentials (EPSPs) and this increase persisted for hours (i.e. Long-term).

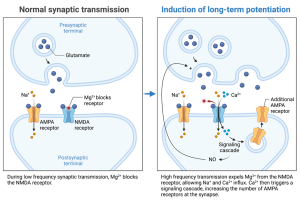

Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) is a powerful form of synaptic strengthening, and although its precise role in memory remains a subject of ongoing research, the underlying mechanism is well-established. LTP crucially involves NMDA receptors, a specialized type of glutamate receptor. These receptors possess a unique characteristic: they only open when both glutamate binds to them and the receiving neuron (postsynaptic cell) is already partially depolarized.

Neuroscientists can artificially induce LTP in the laboratory. They can either directly depolarize the postsynaptic neuron using a tiny electrode or stimulate the sending neuron (presynaptic cell) repeatedly. This repeated stimulation causes the release of glutamate, which activates other glutamate receptors (like AMPA receptors) and partially depolarizes the postsynaptic cell.

When the postsynaptic neuron is partially depolarized, subsequent glutamate release can now activate the NMDA receptors. Importantly, NMDA receptors allow calcium ions (Ca2+) to flow into the postsynaptic cell. This influx of calcium triggers a cascade of events, activating enzymes (protein kinases) that ultimately strengthen the connection between the neurons (synapse).

This strengthening can either be presynaptic or postsynaptic. In the latter case, the kinases phosphorylate AMPA channels, causing them to become more active and/or causing more to be inserted into the membrane. In both cases, the postsynaptic response is enhanced. In some cases, the phosphorylation triggered by the Ca2+-dependent kinase induces the synthesis of nitric oxide which diffuses back to the presynaptic terminal and increases the release of neurotransmitter. Nitric oxide in this case acts as a retrograde signal since it transmits a message backwards, from the postsynaptic to the presynaptic cell.

Media Attributions

- Private: PairedPulseDepression_C6

- Private: PairedPulseFacilitation_C6

- Private: PostTetanicPotentiation_C6

- Private: LongTermPotentiation_C6

- Private: BlissandLomo_C6

- Private: NomalvsLongtermPotentiation_C6