2 The Generic “Brain Cell”

Learning Objectives

Learn the cellular features of neurons (and glial cells)

- Neurons make proteins based on instructions found in the DNA

- Mitochondria synthesize ATP, a common energy currency used to drive cellular processes.

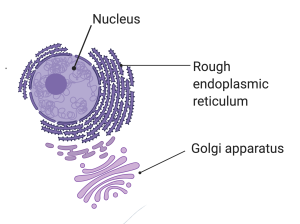

- Proteins are synthesized and processed in the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) and Golgi apparatus.

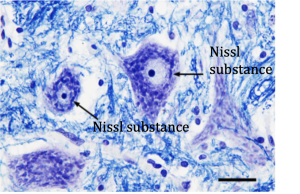

- Nissl substance is a defining characteristic of Neurons as seen in stained preparations.

There are 2 major cell types within the nervous system: Neurons and Neuroglia. Neurons are cells that transmit electrical and chemical information. Historically, neuroglia, or just glia for short, were thought to play supporting roles in the nervous system. While glia are still appreciated for the ways they assist the function of neurons, recent research has revealed that glia are directly involved in some of the signaling that takes place in the nervous system. This has led to an exciting paradigm shift in neuroscience that we will touch on briefly in the chapter on Glia.

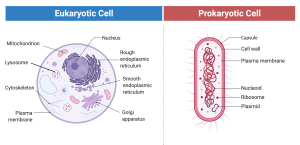

All living things (if we don’t consider a virus a living thing, which is an interesting question on its own) are composed of cells. The cell is the fundamental unit of all life today. Cells come in a wide variety of sizes and shapes; however, there are only two fundamental types: eukaryotic and prokaryotic. The word prokaryotic, which literally means “before the nucleus,” describes cells of bacteria and archaea, the latter being a newly described domain of life. These cells lack internal membranes, which means they do not have membrane-bound internal organelles such as a nucleus. The word eukaryotic, literally “true nucleus,” describes the cells that make up all other forms of life, both plants and animals.

Since “brain cells” are found in animals, they must be eukaryotic. That means they not only have a nucleus, but also a collection of very interesting organelles, organized and most clearly described in terms of the arrangement of internal membranes. Whereas the organelles found in brain cells are the same ones found in most eukaryotic cells, we will see that their functions are highly adapted to the unique functions of brain cells.

The Nucleus

Unlike prokaryotes, with their genetic information (i.e. genes) scattered throughout the cell, the eukaryotes carefully package their genes in a double membrane (i.e. two layers of membrane). Genes, in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, are made of DNA. What is DNA? DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid, is a polymer (literally “many units”). Polymer is a general term for a chemical that is composed of repeating units, often arranged in a long string. In the case of DNA, the repeating units are called nucleotides and there are four of them: Adenine, Thymine, Guanosine and Cytosine (ATGC). One of the truly amazing discoveries of the past century is that life in all of its amazing diversity and complexity is encrypted in the sequences of just these four letters as they are found in the large polymers of DNA.

DNA holds all the instructions for building and running a cell, but it doesn’t do any of the actual “work” itself. Think of it as a master blueprint. The cell uses this information to create all its components and put them in the right places.

How a cell does this is quite complex, but here’s the simplified version:

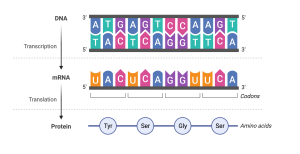

First, the information in DNA’s nucleotide sequence is transcribed, or copied, into RNA (ribonucleic acid). Like DNA, RNA is a string of nucleotides. However, there are a few key differences:

- RNA nucleotides contain an oxygen atom that’s missing from DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) nucleotides.

- While both DNA and RNA use adenine (A), guanine (G), and cytosine (C), RNA uses uracil (U) instead of thymine (T).

Despite these differences, RNA polymers are very similar to DNA. Where DNA has an A, G, or C, RNA will have the same. And as you might guess, where DNA has a T, RNA will have a U.

The process of transcribing DNA into RNA is like the process performed by the transcriptionist in a doctor’s office who transcribes the doctor’s notes, which had been dictated into a tape recorder, into a written document. (Among other things, this avoids the problem of having to decipher the horrible handwriting notorious among physicians.) Unlike DNA, which is sequestered in the nucleus (at least in eukaryotic cells), the RNA carries the information out of the nucleus to the rest of the cell. Here the RNA becomes translated into protein. Just as one language can be translated into another, the information in RNA, with its four letters, is translated into protein, which is formed from 20 different letters. Just like RNA (and the DNA from which it came), the 20 letters, which are amino acids in the case of proteins, are arranged in a unique linear sequence; that is, a polymer. Each of the 20 amino acids that make up all of the proteins in all of the cells in all living things (at least on this planet), is specified by unique permutations of three of the four nucleotides. For example, the three-letter sequence (called a codon) GAA “spells” Glutamic acid (abbreviated Glu or E) and the three-letter sequence GAC “spells” Aspartic acid (abbreviated Asp or D).

If you are a real math wiz, you may have figured out already that there are 64 possible ways that four nucleotides can be arranged into 3-nucleotide sequences (43 = 64). However, I mentioned that only 20 different amino acids make up all of the proteins found in the cell. Thus, there are more “words” in the genetic code than are needed to make proteins. Because of this, we say that the genetic code is degenerate. This is a nasty sounding word that just means that most amino acids are coded by more than one three letter sequence of nucleotides. We will come back to proteins later and look at how they work, that is, how they make cells work. For now, it is enough to know that proteins do the “work” specified by the genes, composed of DNA, and these are located in the nucleus.

Mitochondria

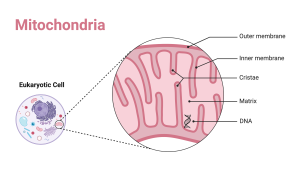

If you know anything about cells, you probably have heard of mitochondria as being the “powerplants of the cell.” They are the cool organelles that look like little bacteria parked strategically throughout the cell. In fact, an interesting digression that I cannot completely resist touching on is that it is probably not a coincidence that these double-membrane organelles resemble bacteria. There is a pretty good chance that mitochondria originated a long, long, long time ago from symbiotic bacteria that lived in cells that were the precursors to the modern eukaryotic cell. According to the endosymbiotic theory, made popular by Lynn Margulis at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, in exchange for a nice wet place to hang their hat and a great meal plan, the bacteria provided lots of ATP, a convenient energy currency used by the cell to fuel various energy requiring processes. The arrangement worked out well enough that the two cells decided to live together permanently. One of the rather odd features of mitochondria that would otherwise be inexplicable is the presence of a little bit of their own DNA. Although the genes encoded by this DNA make only a few of the proteins that are unique to mitochondria (most of the proteins are coded by the nuclear genes), their presence is useful to geneticists since it allows genes to be traced exclusively through the maternal line since our mitochondria were a gift from our mothers (remember that on Mother’s day).

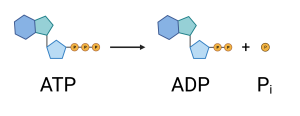

Back to the main story line, mitochondria are best known for their ability to convert the energy in food (i.e. sugar, fatty acids, and amino acids) into ATP, adenosine triphosphate. Cells use ATP, specifically the conversion of ATP to ADP (adenosine diphosphate) and Pi (free phosphate), to drive many of its energy-requiring processes. In case you are interested, the removal of the third phosphate, called the γ phosphate, from ATP, leaving adenosine with only two phosphates (α and β; you guessed it if you know the Greek alphabet), releases approximately 7,300 calories of energy per mole of ATP, where a mole means 6 x 1023 molecules. (For your reference, especially if you regularly read the nutritional labels on food, 1000 calories to a scientist is the same as 1 Calorie, with a capital C, to a nutritionist. You might try, just for fun, to calculate how many molecules of ATP you can make from each bowl of cheerios you eat in the morning.)

Beyond their well-known role in generating ATP (the cell’s energy currency), mitochondria perform another crucial function, especially vital for neurons: they actively pump calcium ions (). Mitochondria move calcium from the cell’s cytoplasm (the fluid outside the organelles) into their inner compartment, the mitochondrial matrix. We’ll explore later how important calcium ions are for both neurons and glia.

Thanks to this mitochondrial pump and other pumps, the concentration of free in the cytoplasm is kept incredibly low—typically less than 100 nanomolar (nM), or M. To put this in perspective, that’s even less free calcium than what’s found in highly purified “deionized” water used in labs!

Later, we’ll see how neurons use temporary increases in free to trigger the release of neurotransmitters at synapses. For now, consider this sobering thought: aside from extreme trauma, the ultimate cause of most deaths is likely related to an uncontrolled rise in free calcium ions in brain cells (above 100 nM). This often happens during a cardiovascular event that disrupts the delivery of oxygen or glucose to the brain’s homeostatic centers.

Endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi Apparatus

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi Apparatus are an extensive arrangement of tubes and sacs involved in making proteins, which then get sent throughout the cell to do the jobs they are designed for. For our purposes, we won’t need to concern ourselves too much with this general function of the ER, but one of its other functions is critical for synapses. The membrane of the ER contains a protein that actively pumps Ca2+ from the outside to the inside of the ER. That is, it moves Ca2+ out of the cytoplasm (remember, this is the stuff inside the cell, but outside the organelles).

Notice, I refer to this as a “pump”, which connotes the active forcing or pushing of the Ca2+ out of the cytoplasm in the same way a water pump might push water out of your row boat that has a leak in the bottom. The Ca2+ needs to be pushed because there is more of it inside the ER than inside the cytoplasm (i.e. its concentration is higher in the ER). If there is a pathway for Ca2+ to move across the membrane of the ER (more of this later), the Ca2+ will spontaneously flow out of the ER. The pump works against this tendency and uses energy it gets from ATP to actively stuff the Ca2+ back into the ER. The upshot of this is that this is one of the processes in the cell that, along with the mitochondria which we discussed above, keeps the concentration of Ca2+ in the cytoplasm really, really low. The importance of this will become clearer when we discuss synapses.

Before leaving the ER and Golgi, I should mention a feature that is unique to neurons. Proteins are made in the soma (cell body) of the neuron and are transported out to the far reaches of the neuron’s axon and dendrites. Many neurons, especially the large ones that project their axons over great distances, must exert great effort to stocking and restocking itself with proteins. To do so, these neurons require lots of ER packed into the relatively small space of the soma. In fact, the ER is so dense it can be seen in the light microscope using standard histological stains. This staining is call Nissl substance and its presence is a sure sign that the cell containing it is indeed a neuron.

Media Attributions

- Eukaryotic Cells

- Molecular Structure of DNA

- Mitochondria

- ATP to ADP

- ER and Golgi

- Nissl

Electrically excitable cells of the nervous system that receive and transmit signals to different areas of the body.

Non-neuronal cells that are not electrically excitable.