3 Cells of the Nervous System: The Neuron

Learning Objectives

Know the common features of neurons.

- Dendrites

- Cell body (Soma)

- Axon

- Synapse

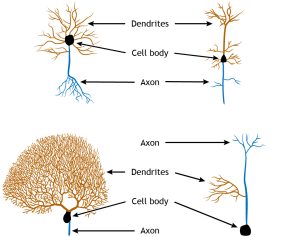

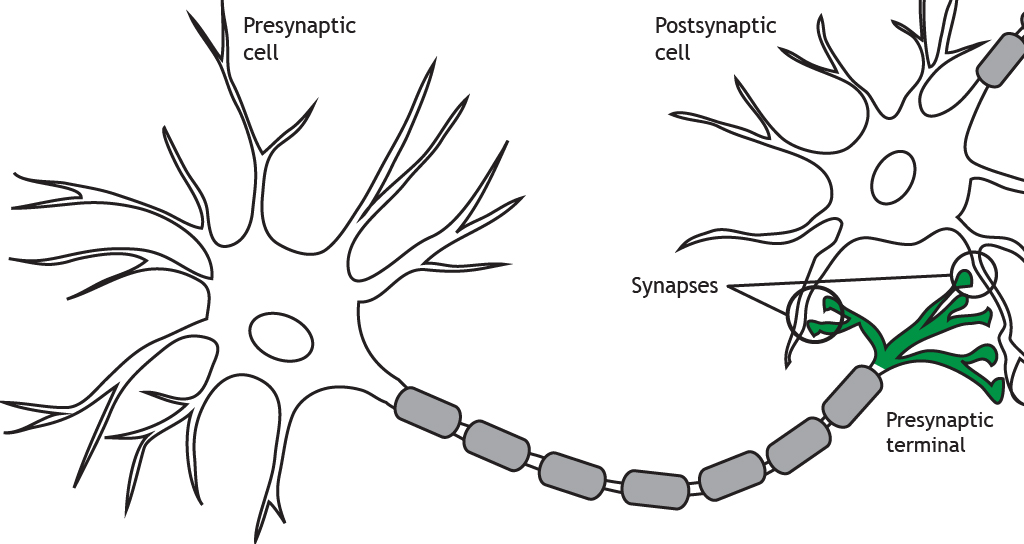

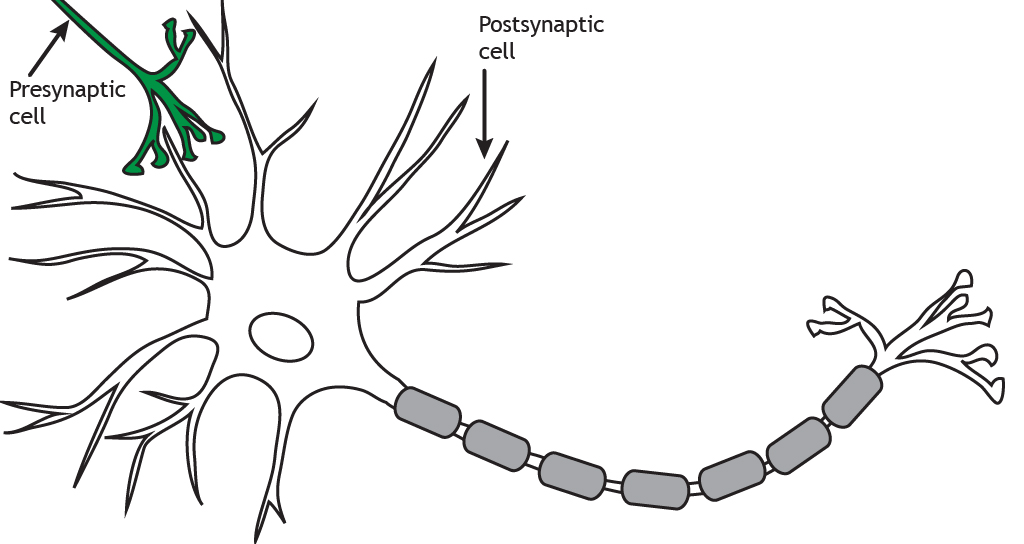

Neurons, sometime also just called nerve cells, carry out most of the actions of the nervous system. Their main function is to send electrical signals over short and long distances within the brain and throughout the body, and they are electrically and chemically excitable. The function of the neuron is dependent on its structure. The typical neuron consists of the dendrites, cell body, axon (including the axon hillock), and presynaptic terminal. Although these typical structural components can be seen in all neurons, the overall structure can vary drastically depending on the location and function of the neuron. Some neurons, called unipolar, have only one branch from the cell body, and the dendrites and axon terminals project from it. Others, called bipolar, have one axonal branch and one dendritic branch. Multipolar neurons can have many processes branching from the cell body. Additionally, each of the projections can take many forms, with different branching characteristics. The common features of cell body, dendrites, and axon, though, are common among all neurons.

The number of neurons in the adult human brain, according to our current best estimate, is close to 86 billion. This number was calculated using a revolutionary technique, the isotropic fractionator or “brain soup”, developed by Brazilian neuroanatomist Suzana Herculano-Houzel. To put this number in context, we have about 37 trillion cells in the whole body, so neurons in the brain make up about 0.2% of all cells in the body. Below are some unique characteristics that neurons have in common.

1. Neurons are electroactive, which means that they are charged cells that can change their charge.

2. Neurons are specialized for rapid communication.

Many cells are capable of sending and receiving chemical signals across long distances and time scales, but neurons are able to communicate with a combination of electrical and chemical signals in a matter of milliseconds. Additionally, the shape of neurons and the organization of the neurons on a microscopic level make them effective for sending signals in a very specific direction.

3. Neurons are “forever” cells.

We are constantly replacing non-neuronal cells. For example, the cells in our bones replace themselves frequently at a rate of about 10% each year. Our body makes new skin cells to replace the dying skin cells on the surface so that we have a “new” skin every month. The cells along the inside of our stomachs, exposed to very harsh acidic conditions, get replaced about every week. About 100 million new red blood cells are created every minute! On the other hand, the mature nervous system generally does not undergo much neurogenesis: the creation of new neurons.

The neurons that we have after development are the ones that we will keep until we die and this permanence of neuronal count makes them different from almost every other cell of the body. However, the idea of adult neurogenesis is a topic of debate among neuroscientists since some areas, like the olfactory system and the hippocampus, display new nerve cell production.

4. …But, neurons can change.

Even though new neurons are not created in most areas of the brain, neurons still have the capability to change in their structure and function. Some of these changes, such as physical changes to the structures of the input sites of the neurons, are believed to last for a lifetime.

We use the word plasticity to describe the ability for the brain to alter its morphology. This term is derived from the Greek plastikos, meaning “capable of being shaped or molded”—think of plastic surgery, where a person changes their physical appearance.

Also, neurons do have the capacity to repair themselves to some extent. Neurons of the Peripheral Nervous System may get injured or completely destroyed as a result of trauma to the body. Afterwards, those injured neurons can regrow to connect once again with their original partner. This regrowth seems to depend on a few chemical signals that the body produces, such as nerve growth factor and brain derived neurotrophic factor. However, this process is often very slow, and does not always successfully restore the nervous system to the way it was pre-injury.

Dendrites

One of the main features of neurons that make them unique from other cells are the tubular extensions (processes) that extend out from the main cell body of the neuron (called the soma). These arm-like extensions include dendrites and axons. These extensions allow neurons to communicate with other neurons or specialized cells. As a general rule (although all rules have exceptions), the dendrites receive signals from other neurons and pass those signals to the soma whereas the axons (and as a rule, neurons only have one of these) send the signals away from the soma to make connections with other cells. In many neurons, the dendrites form an extensively branching pattern that looks like the branches of a tree. Thus, they are sometimes referred to as the dendritic arbor (arbor means tree in Latin). The dendrites are often covered with tiny little knobs, called dendritic spines. You can imagine them looking like buds along a tree branch. The spines are where inputs from other neurons are received. In some recent research, neuroscientists have actually created videos showing these spines changing shape while the animal being studied is learning something. Presumably, these shape changes are one of the ways connections between neurons are modified by experience and function to store information during learning.

Cell Body

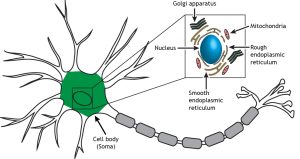

Information that arrives through the many dendrites of a neuron eventually filters into the cell body, or the soma, of the neuron. The cell body (shown below in green) contains the nucleus and cellular organelles, including the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, ribosomes, and secretory vesicles. The nucleus houses the DNA of the cell, which is the template for all proteins synthesized in the cell. The organelles (illustrated in the inset box) in the soma are responsible for cellular mechanisms like protein synthesis, packaging of molecules, and cellular respiration.

The cell body is responsible for deciding whether to pass a signal onto the next cell. The cell membrane of the soma performs a complex set of “cellular arithmetic” that weighs all of the incoming signals: excitatory, inhibitory, and modulatory signals. After all of the calculations have been performed, the membrane decides to send a signal, either a “yes” or “no” output, which travels down the axon.

The Axon

As mentioned above, the axon is the other type of projection found in neurons. Its job is to send information out from the soma where it connects (i.e. synapses) onto its targets. In most cases, the axon also branches extensively just like the dendrites. It is estimated that on average each neuron connects to 10,000 other neurons. The axons on some neurons do not travel far from the soma. Their connections are relatively close. This is typical of what are called interneurons. They make the numerous connections involved in processing information before passing it on along a projection neuron to another part of the brain or even outside the brain (e.g. to muscles).

The axons of projection neurons can be quite large. For example, the motor neurons that project out of your spinal cord and send their message down to the muscles controlling your big toe may be several feet long (depending on the length of your leg). In some animals, like a giraffe, they may be several yards in length! To appreciate how extraordinary this is you have to remember that these axons are part of a single neuron (i.e. a single cell). To get some perspective, if the soma of one of your motoneurons in the spinal cord was the size of a basketball, its axon would be about 2 miles long!

Since all of the proteins and organelles in a neuron are made in the soma, some of them must be transported all the way down this long axon to its end, a structure called the axon terminal. Furthermore, after these proteins and organelles become damaged, they need to be shipped all the way back to the soma for recycling. Obviously, there is a lot of movement up and down the axon. Little motors (made of proteins) called dynein and kinesin carry this cargo along tracks made of the protein tubulin. As its name suggests, tubulin forms into long tubes, called microtubules, which run the entire length of the axon.

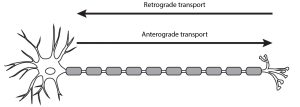

Axoplasmic Transport

Axoplasmic transport refers to the movement of material within the axon. Organelles, vesicles, and proteins can be moved from the cell body to the terminal via anterograde transport or from the terminal to the cell body via retrograde transport. Anterograde transport can be either fast or slow.

Microtubules run the length of the axon and provide the cytoskeleton tracks necessary for the transportation of materials. Proteins aid in axoplasmic transport. Kinesin is a motor protein that uses ATP and is used in anterograde transport of materials. Dynein is another motor protein that also uses ATP, but is used in retrograde transport of materials.

Axoplasmic transport has been recorded using very high resolution video cameras (see, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i3hxq4XPez0 ) and looks surprisingly similar to a busy highway in Southern California or Beijing, China with vehicles moving rapidly in both directions along the crisscrossing roads. If you want to see a cool animation of a kinesin protein walking along a microtubule, look here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y-uuk4Pr2i8 .

To give you a sense of the importance of this transport “railway,” if a nerve axon is cut (e.g. if you seriously cut your arm), every part of the axon after the cut (i.e. on the other side of the soma) will die since it has been disconnected from its home base. Fortunately, the part of the axon before the cut can remain alive and, as long as the damage was not too disruptive to the overall structures in the arm, the axon can regenerate and grow out from the cut and reconnect with the muscles it was originally controlling. (Caution: don’t try that experiment at home, or ever, just believe me.)

Of course, a discussion of axons would not be complete – in fact, it would not even have really started –without mention of action potentials. If you ever heard anything about neurons, the nerve impulse was probably mentioned. This refers to an electrical signal that transmits rapidly down the axon. We will look at this process in more detail later.

Action Potential

The axon transmits an electrical signal—called an action potential—from the axon hillock to the presynaptic terminal, where the electrical signal will result in a release of chemical neurotransmitters to communicate with the next cell. The action potential is a very brief change in the electrical potential, which is the difference in charge between the inside and outside of the cell. During the action potential, the electrical potential across the membrane moves from a negative value to a positive value and back.

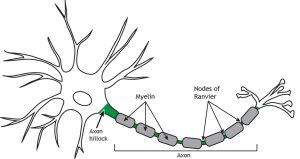

Myelin

Many axons are also covered by a myelin sheath, a fatty substance that wraps around portions of the axon and increases action potential speed. There are breaks between the myelin segments called Nodes of Ranvier, and this uncovered region of the membrane regenerates the action potential as it propagates down the axon in a process called saltatory conduction. There is a high concentration of voltage-gated ion channels, which are necessary for the action potential to occur, in the Nodes of Ranvier.

The Synapse

Before we go any further, full disclosure. I am kind of a synapse fanatic. I have two vanity license plates on my cars. One is SYNAPSE and the other is SYNAPS2. As I am often asked in parking lots, “what is a synapse?” Well, so nice of you to ask. A synapse refers to a specialized connection between two neurons or between a neuron and a muscle cell. The purpose of synapses is to transmit electrical signals (e.g. an action potential or nerve impulse) from one cell (the presynaptic cell) to another (the postsynaptic cell)

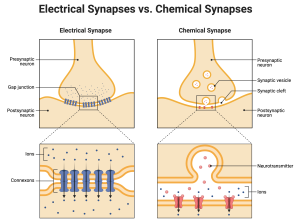

There are two ways synapses do this. One way is by directly passing the electrical signal between the two cells. This is called an Electrical Synapse. The other way is by passing a chemical, called a neurotransmitter, from one cell to the other. This is called a Chemical Synapse. We won’t consider electrical synapses in this course. They play a much less prominent role than chemical synapses, especially in adult animals. They don’t do anything very clever, they just pass the signal, like a runner in a relay race passes the baton. Their principle advantage is speed and reliability. Chemical synapses, on the other hand, are extremely clever. They can, in some cases, simply pass the baton to the next cell, but they can do so much more.

For example, some synapses do the opposite of passing the baton. They inhibit the postsynaptic cell, making it less likely to generate its own signal. Your brain is full of both excitatory and inhibitory synapses, with a slight majority of the latter. These synapses allow your neurons to form complex networks of interconnected neurons. Think of the internet – the world wide web. If you imagine each computer as a neuron, just as in the brain, every computer is ultimately connected to every other computer in the world, not directly, but through its connections to other computers, which are connected to other computers, which are connected to … (you get the point). The brain is thought to be like that, but here is the most amazing thing. Just like computers, neurons can alter their messages. They don’t always have to say the same thing. Furthermore, they don’t always listen with the same level of care. The signals can sound louder or quieter. We refer to this as synaptic plasticity, which means the synapses can change. The communication can get stronger, weaker or change in other ways. Moreover, since some synapses are excitatory and others inhibitory, the possible combinations of signals within a network of neurons can be astronomically large.

The Chemical Synapse

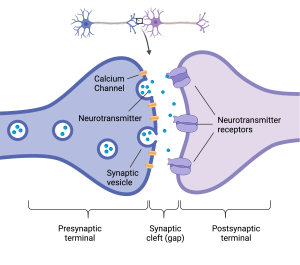

Chemical synapses use neurotransmitters to communicate. Chemical synapses can vary depending on the nature of the synapse. A chemical synapse is a larger distance, about 15–40 nm across. Adjacent neurons connected by chemical synapses do not share cytoplasm.

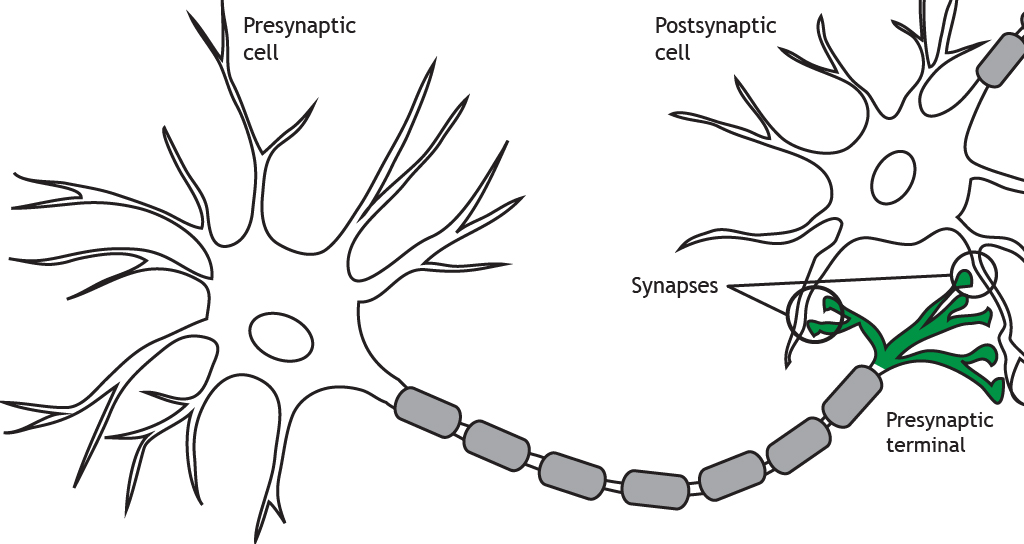

Presynaptic versus Postsynaptic

The axon terminates at the presynaptic terminal or terminal bouton. The terminal of the presynaptic cell forms a synapse with another neuron or cell, known as the postsynaptic cell. When the action potential reaches the presynaptic terminal, the neuron releases neurotransmitters into the synapse. The neurotransmitters act on the postsynaptic cell. Therefore, neuronal communication requires both an electrical signal (the action potential) and a chemical signal (the neurotransmitter). Most commonly, presynaptic terminals contact dendrites, but terminals can also communicate with cell bodies or even axons. Neurons can also synapse on non-neuronal cells such as muscle cells or glands.

The terms presynaptic and postsynaptic are in reference to which neuron is releasing neurotransmitters and which is receiving them. Presynaptic cells release neurotransmitters into the synapse and those neurotransmitters act on the postsynaptic cell.

Synaptic Transmission

Before we move on to the next chapter, I would like to give you a quick overview of the events that take place at a chemical synapse. As mentioned, all synapses have a presynaptic (sending) part and a postsynaptic (receiving) part. If you were to pass a synapse on the street you would be able to recognize the presynaptic element because it is full of tiny, ball-shaped organelles called synaptic vesicles. Like all organelles in eukaryotic cells, the synaptic vesicles are made of a membrane, which separate the inside from the outside. The outside faces the cytoplasm and the inside contains the chemical, which we refer to in this case as a neurotransmitter. After synthesizing these chemicals, the presynaptic cell packs them into the vesicles, where they remain until the presynaptic cell is ready to talk.

Another important feature of the presynaptic cell is the Ca2+ channels in the cell membrane. We will say more about ion channels later, but for now it is sufficient to think of them as passageways that allow the Ca2+ ions to move across the presynaptic cell membrane. Like many channels, these have gates. That means, the passageway can be kept closed or open. What happens is this, when a nerve impulse passes down an axon into its terminal, the electrical signal opens the tiny gates on the Ca2+ channels. Since there is a lot, lot more Ca2+ outside the cell than inside, once those gates open, Ca2+ ions rush into the presynaptic cell. The Ca2+ then binds to proteins on the synaptic vesicle and make the membrane of the synaptic vesicle fuse with the membrane of the nerve terminal. The fusion of these membranes causes the vesicle to open up to the outside of the presynaptic terminal and dump its contents (the neurotransmitter) into the gap between the pre- and postsynaptic components of the synapse. This process, called exocytosis, is how neurotransmitter is released at all synapses, excitatory and inhibitory. The difference between synapses reside in the postsynaptic part.

To be able to respond to the released neurotransmitter, the postsynaptic cell contains specialized proteins in their cell membrane called neurotransmitter receptors. These proteins recognize the neurotransmitter and open up (or close) a gate in the ion channels they control. These ion channels will either let positive ions, like Na+ or K+ pass through, in the case of excitatory synapses or they will let Cl- ions through, in the case of inhibitory neurons. We will say more about these features later, but for now I will end by mentioning one other important feature of chemical synapses, the clean-up crew.

After the neurotransmitter is released into the synaptic gap, it must be removed, otherwise it will just keep activating the receptors on the postsynaptic cell forever. To work properly, the neurotransmitter has to be “turned off”. There are different ways this happens. I will mention three here. First, in some synapses, the neurotransmitter just diffuses away into the surrounding medium. As you might imagine, this is fairly slow and therefore not adequate for the synapses that transmit fast or rapidly changing messages. The second method, called neurotransmitter reuptake, is found at synapses that are too busy to wait for the neurotransmitter to just diffuse away. In these synapses, there is a transporter in the membrane of the presynaptic cell that recaptures the neurotransmitter and pulls it back into the presynaptic terminal where it can be recycled and packaged into new synaptic vesicles.

These kinds of reuptake transporters became popularized with the proliferation of the antidepressant drugs like Prozac. These drugs block the reuptake of certain neurotransmitters like Serotonin resulting in a transient elevation of this neurotransmitter. The therapeutic effect of these drugs is complicated and not completely understood, but they all begin by interfering with the normal process by which synaptic messages are terminated.

The third method is found at the fastest synapses. These synapses need to turn on fast and turn off fast. The synapse between a nerve and muscle, called the neuromuscular junction, is one of these. For you to move your arms or fingers (think of playing the piano) some muscles need to rapidly activate at the same time opposing muscles need to turn off. If a muscle synapse doesn’t turn off, you experience it as a spasm, not a good look when you are playing a concerto in front of a packed audience. Neuromuscular junctions cannot afford to wait around for the neurotransmitter, which in this case is called acetylcholine, to get taken back into the presynaptic terminal. Instead, it places an enzyme in the synaptic cleft (the space between the presynaptic and postsynaptic terminal) that inactivates the acetylcholine. The enzyme, called acetylcholinesterase, breaks acetylcholine into its two parts, acetate and choline. Neither of these can activate the receptor, so the message stops. In case you are curious, the choline gets recycled back into the presynaptic terminal, where it is recombined with acetate and repackaged into new synaptic vesicles. Not to end this chapter on a downer, but I would be remiss if I didn’t provide a real-world example of this process.

Biological Weapons

Nerve gas, like Sarin, unfortunately makes the news every now and then as terrorists or despots (what’s really the difference?) release a nerve agent onto the public. The action of these agents is simple, but deadly. They inhibit the enzyme acetylcholinesterase. What will this do? Well, victims will be unable to turn off muscle contraction because their acetylcholine will continue activating its receptors on the muscle cell. They will experience seizures, but even worse, they will stop breathing. The movement of air into and out of your lungs requires the activation of muscles like the diaphragm that enlarge the lungs and cause air to suck in. To breathe out, these muscles must relax. I think you can imagine the rest…

Key Takeaways

- Each structural component of the neuron has an important function

- Overall structure of the cell can vary depending on location and function of the neuron

Test Yourself!

Attributions

Portions of this chapter were remixed and revised from the following sources:

- Foundations of Neuroscience by Casey Henley. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

- Open Neuroscience Initiative by Austin Lim. The original work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Media Attributions

- Neuron-Types

- Dendrites

- Soma

- AxonalTransport

- Myelin

- Car liscence plate

- Elec vs. Chem synapse

- Presynaptic-Terminal

- Postsynaptic-Cell

- synapse

The cell body of a neuron. Where the nucleus and organelles are located.

Movement from the cell body to the axon terminals

Movement from the axon terminals toward the cell body

A motor protein that uses ATP in anterograde transport of materials

Motor protein that uses ATP in retrograde transport of materials

The electrical signal transmitted by the axon of a neuron.

The junction of the cell body and the axon. Where action potentials are generated.

Chemicals that are released by neurons or other cells that bind to receptors on other neurons or cells to elicit change in the target cell.

The electrical charge of the neuron (measured in mV).

fatty substance that covers the axons of some neurons

Breaks between adjacent sheaths of myelin on the neuron axon.

A synapse where 2 cells are separated by a synaptic cleft that chemical neurotransmitters must cross to signal between cells.

The end of the axon furthest from the cell body.

Release neurotransmitters into the synapse

Cells that receive neurotransmitters