9 The Synapse

Learning Objectives

- Understand the difference between Electrical and Chemical Synapses

- Understand the general operation of the Chemical Synapse

For neurons to actually “do” anything, they must broadcast their message to other cells. These other cells may be muscle cells, which allow the animal to interact with the world, or they may be other neurons, which allow the nervous system to process sensory information and decide what to do about it.

Electrical vs. Chemical Synapses

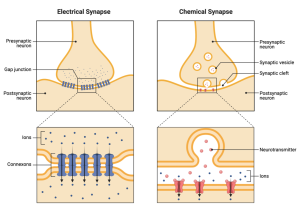

Neurons communicate at structures called synapses, of which there are two kinds, electrical and chemical. Electrical synapses are the simplest. In this case, the cells are connected by junctions, called gap junctions, that connect the inside of one cell to the inside of another. These gap junctions allow ions to pass through. Thus, an action potential (or a passive potential) in one will pass directly to the other cell. Simple. Chemical synapses, on the other hand are much more complicated. In this case, the cells are not directly connected together but they are separated by a gap between the two cells, called the synaptic cleft or gap. To communicate across this gap, the presynaptic cell (i.e. the cell doing the talking) releases a chemical into the synaptic cleft. This chemical is called a neurotransmitter. The neurotransmitter diffuses across the gap and binds to receptors on the postsynaptic cell (i.e. the cell doing the listening). The binding of the neurotransmitter to the receptor then changes the activity of the postsynaptic cell.

The main features of each type of synapse are listed below:

| Electrical Synapse | Chemical Synapse |

| Fast | Slow (at least 1-2 ms delay). |

| Reliable | Susceptible to disease/injury |

| Unchanging | Changeable (i.e. plastic) |

Since the first two factors listed above favor electrical synapses (i.e. they are faster and more reliable), you might guess that the last factor is the game changer and you would be right. Most synapses are chemical and the proportion that are chemical increases with increasing complexity of the nervous system. What is the benefit of being changeable? This property, called plasticity, allows communication at the synapse to change during the course of development and learning. It is what prevents animals like ourselves from always behaving exactly the same. We change our behavior as we develop and learn and this change occurs at our synapses. I won’t say anything more about electrical synapses because they are not relevant to the questions we will be addressing this semester. We turn to the chemical synapse

The Chemical Synapse

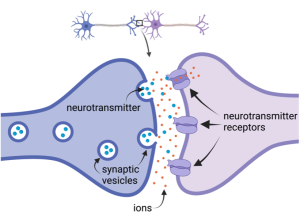

The general operation of a chemical synapse was described briefly above. An additional feature is that the neurotransmitter is contained inside tiny organelles called synaptic vesicles and these vesicles are clustered in the presynaptic terminal near the membrane facing the synaptic cleft. When the presynaptic cell is at rest, these vesicles more or less stay put and the neurotransmitter remains inside the nerve terminal. (As we will see later, this is not entirely true, but we can ignore that detail for now.) When either an action potential or a passive potential is generated in the presynaptic cell, we say the cell is active. If the depolarization spreads into the nerve terminal, some of the synaptic vesicles are induced to fuse with the membrane of the nerve terminal. This fusion exposes the inside of the synaptic vesicle to the outside of the cell and the neurotransmitter held in the vesicles diffuses out into the synaptic cleft.

Since the gap is normally quite small, the neurotransmitters don’t have to diffuse far before encountering receptors in the membrane of the postsynaptic cell (e.g. on the muscle or dendritic spine). The interaction of the neurotransmitter and the receptor protein is like a key fitting into a lock. The neurotransmitter molecules bind precisely to the receptor and change its shape. We will consider more complicated responses later, but at virtually all chemical synapses, the primary receptor is an ion channel. The gates on these channels open when the neurotransmitter binds. These are an example of the ligand-gated ion channels discussed in chapter 6.

The opening of these neurotransmitter-gated ion channels either depolarize or, in the case of inhibitory synapses, hyperpolarize the post-synaptic cell. We will discuss these details in later chapters.

Media Attributions

- Private: ElectricalvsChemicalSynapse_C6

- Private: ChemicalSynapse_C6